Validate the Self Stigma Of Seeking Help (SSOSH) scale in a population of students of a medical school for its use in Colombia.

MethodsWe included 384 medical students from the city of Medellín. Initially, two direct translations were made, two back translation and one pilot test. The internal consistency, test-retest repeatability and structural, convergent, divergent and discriminative construct validity were then evaluated.

ResultsA easy-to-understand and to fill out Spanish version was obtained. The internal consistency of the scale was adequate (Cronbach’s alpha = .80; 95%CI, .77–.83) as well as the test-retest repeatability (CCI = .77; 95%CI, .63–.86). The Confirmatory Factor Analysis showed a good fit with the one-dimensional structure (RMSEA = .073; IC90%, .056–.089; CFI = .968; TLI = .977; WRMR = .844). The convergent validity was supported by the correlation with the Public Stigma scales (ρ = .39) and Attitudes towards Seeking Help (ρ = –0.50) and the divergent validity with the Social Desirability scale (ρ = –0,05). When examining the discriminative validity, differences were found between the scores of those who would be willing to seek professional help when having a mental health problem and those who probably would not (Difference of means = 4.9; 95%CI, 2.99–6.83).

ConclusionsThe Colombian version of the SSOSH is valid, reliable and useful for the measurement of the Self-stigma associated with seeking professional help in the university population of the Colombian health sector. Its psychometric properties must be investigated in populations of other programs and outside universities.

Validar la escala de Autoestigma por Búsqueda de Ayuda (ABA), conocida en inglés como Self-Stigma of Seeking Help (SSOSH), en una población de estudiantes de una facultad de Medicina para su uso en Colombia.

MétodoSe incluyó a 384 estudiantes de Medicina de la ciudad de Medellín. Se realizaron 2 traducciones directas, 2 en sentido inverso y 1 prueba piloto. Luego se evaluó la consistencia interna, la reproducibilidad prueba-reprueba y la validez del constructo estructural, convergente, divergente y discriminativa.

ResultadosSe obtuvo una versión en español de fácil comprensión y diligenciamiento. La consistencia interna de la escala fue adecuada (alfa de Cronbach = 0,80; IC95%, 0,77–0,83) al igual que la reproducibilidad prueba-reprueba (CCI = 0,77; IC95%, 0,63–0,86). El análisis factorial confirmatorio mostró un buen ajuste con la estructura unidimensional (RMSEA = 0,073; IC90%, 0,056-0,089; CFI = 0,968; TLI = 0,977; WRMR = 0,844). La validez convergente se mantuvo con la correlación con las escalas de estigma público (ρ = 0,39) y de actitudes hacia la búsqueda de ayuda (ρ = –0,50) y la validez divergente con la escala de deseabilidad social (ρ = –0,05). Al examinar la validez discriminativa, se encontraron diferencias significativas entre las puntuaciones de quienes estarían dispuestos a buscar ayuda profesional en caso de tener un problema de salud mental y quienes probablemente no lo harían (diferencia de medias, 4,9; IC95%, 2,99–6,83).

ConclusionesLa versión colombiana de la ABA es válida, confiable y útil para la medición del autoestigma asociado con la búsqueda de ayuda profesional en población universitaria del área de la salud de Colombia. Se debe investigar sus propiedades psicométricas en poblaciones de otros programas y no universitarias.

Stigma is defined as a discrediting characteristic that occurs when someone’s attributes are inconsistent with our stereotype, making them appear different and inferior.1,2 If stigma is related to negative beliefs about having mental disorders (MDs) and seeking professional help, it can have two forms: public stigma, which is typical of social groups, and self-stigma, which is the internalisation of these beliefs and prejudices by the person suffering from the disorder.3 Self-stigma of seeking help is the self-perception that affects self-esteem and self-efficacy if mental health care is requested.4 This type of stigma means that treatment is not sought or is delayed, which has negative effects on the prognosis of MDs.5,6 In Colombia, only 38% of those affected by MDs seek health care and the rest do not do so, mainly due to attitudinal barriers, including self-stigma.7–9

Mental health problems are common in university student populations in which self-stigma can act as an access barrier to mental health services that are offered to them.10–13 Some studies have pointed out its role as a predictor of attitudes towards psychological treatment and its relationship with a lower likelihood of seeking services.4,13,14 In particular, medical students have reported a high prevalence of depression and anxiety and exposure to sources of stress such as the acquisition of clinical skills, social expectations and the suffering and death of patients, among others.15–18 In a study on the use of mental health services, 33.7% of medical students reported not seeking psychological help due to the possible impact that this fact would have on their professional career.19 Moreover, 25.3% of the students associated the use of psychological services with weakness and a similar percentage showed concern about what their fellow students might think of them.19

It is important to take into account this construct and its relationship with help-seeking behaviour in the design and evaluation of mental health and wellbeing programmes, because it would allow for a more complete model that would increase the chances for success of interventions to reduce the duration of untreated MDs, which would have great value for public health, since timely care improves the prognosis.20 Therefore, in Colombia an instrument is required to measure self-stigma related to seeking professional help, since its research would provide new and relevant information for understanding the reasons and attitudes why people limit themselves in seeking help and deprive themselves of the positive effects of available mental health care. In addition, a measurement tool is required to identify the manifestations of self-stigma, its distribution in the population and its effects on people's quality of life.

Most of the available tools for measuring stigma associated with seeking help were developed and validated in samples of university students and focus on measuring public stigma, not self-stigma.21–26 The only self-stigma scale related to seeking help that was identified was the one developed by Vogel in 2006: the Self-Stigma of Seeking Help (SSOSH) scale.4 It is a self-applied scale composed of 10 items that measure concerns about the loss of self-esteem that a person would feel if they decided to seek help from a mental health professional. The SSOSH was built under the assumptions of the Classical Test Theory (CTT) and a reflective model. It has been translated, validated and used in several countries and, although in Spain there is a version in Spanish, it lacks published evidence of evaluation of psychometric properties.27

For clinicians and researchers to be able to use the SSOSH scale in Colombia, it is necessary to carry out an adaptation process and an evaluation of its psychometric properties to ensure its validity, reliability and usefulness.28 This study aims to translate it into Spanish, adapt the SSOSH scale to Colombian culture, and evaluate the psychometric properties of the new version in a sample of university students from a medical school.

MethodsThe study had two phases: a) translation and adaptation, and b) evaluation of psychometric properties. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Antioquia.

Translation and adaptationDr David L. Vogel, author of the SSOSH, gave his endorsement for the validation of the instrument in Colombia. Subsequently, a Scale Review Committee (SRC) was formed, made up of a sociologist, a psychologist with experience in university welfare services, and three psychiatrists.

Two official Colombian translators independently translated the instrument from English into Spanish. These translators spoke Spanish as their mother tongue and one of them was a psychologist. The SRC then carried out a synthesis in Spanish of the direct translations. Afterwards, two back-translations of this synthesis were carried out, without the translators (different from the initial ones) having knowledge of the original versions of the scale in English. Finally, the SRC evaluated the two translations and built a preliminary version.

Once the translation process was completed, a pilot test was carried out on a convenience sample of 20 undergraduate students from the Faculty of Medicine. The comprehensibility and interpretation of the items and response categories were examined in order to find possible areas of confusion and make observations with respect to the target population. The items that showed some kind of difficulty were reviewed and modified again by the SRC until the final version was created.

Evaluation of psychometric propertiesParticipantsStudents from the programmes in Medicine, Surgical Instrumentation and Technology in Prehospital Care at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Antioquia (Medellín, Colombia) participated. The inclusion criteria were: being over 18 years old, being active in the academic system and accepting participation.

Each psychometric property required a specific sample size calculation. For internal consistency, a sample size of 320 subjects was calculated using the sample size estimation criteria proposed by Streiner.29 A type I error of 0.05, an expected Cronbach's alpha correlation coefficient value of 0.7, a confidence interval precision of 0.1, and a scale composed of 10 items were assumed. This sample size was also used for the description of items and for the validity of the structural construct, taking into account the recommendations for confirmatory factor analysis.30 For test-retest reproducibility, a sample size of 50 was calculated using the Giraudeau and Mary formula proposed by de Vet28, with a type I error of 0.05, a power of 0.80, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.8 and a confidence interval width of 0.1. For convergent and divergent validity, the sample size was calculated using the formula for correlation with a type I error of 0.05, a power of 0.80, a Spearman correlation coefficient of 0.5 in the alternate hypothesis and 0.1 in the null hypothesis for a total of 65, and it was increased by 10% for possible eventualities. The sample consisted of 72 subjects. For discriminative validity, the sample size calculation was made with the recommendations of Machin et al.31, with the function for comparison of independent means with unknown but equal variances, using an expected standardised mean difference of 0.5, which would be a moderate effect size according to Cohen's criteria32, a type I error of 0.05 and a power of 0.80 for a total of 62, and, by adding 10% for possible eventualities, a sample size was obtained of 69 participants per group.

ProceduresThe contact details of the undergraduate students of the Faculty of Medicine were provided by the Welfare Office of the University of Antioquia. A formal email invitation was sent to all active students in the second semester of 2018 inviting them to voluntarily participate in the research. The email contained, in addition to the invitation, a link to a web page that contained the informed consent form and data protection policy. If the student selected the option to participate voluntarily in the research, they accessed the study instruments to be completed. The data of all the participants were used in the description of items and the evaluation of the internal consistency and the validity of the structural construct.

A random sample of 72 participants was taken for the evaluation of the validity of the convergent and divergent construct. They also filled out the Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help (SSRPH), the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help - Short Form (ATSPPH-SF) scale and the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MC-SDS).

For the evaluation of the test-retest reproducibility, a sample of 50 subjects was randomly selected, who underwent a second application of the SSOSH 15 days later, during which time it is unlikely that significant changes in self-stigma will occur and the memory bias of the participants is avoided.

For the evaluation of the discriminative validity, the form included a dichotomous question about willingness to seek psychological help in case of suffering emotional or psychological problems. A random sample of 69 participants was selected among those who answered affirmatively to the question and 69 among those who answered negatively.

ToolsSelf-Stigma of Seeking Help (SSOSH) scale. It consists of 10 items consisting of statements that are answered according to the degree of agreement using 5 Likert-type response options: 1, strongly disagree; 2, disagree; 3, neither agree nor disagree; 4, agree; 5, strongly agree. The total score is based on the sum of the partial scores for each item and has a range of 10 to 50 points. High scores indicate greater self-stigma. The scale has exhibited good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha, 0.86–0.89) and good test-retest reproducibility (ICC = 0.72). Through confirmatory factor analysis, the authors established that the scale construct was composed of one factor. It has construct validity supported by correlations with the scales of perceived risks (DES), public stigma (SSRPH), attitudes towards seeking help (ATSPPH-SF), self-concealment (SCS) and social desirability (MC-SDS), as well as the Rossemberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-21 (HSCL-21). Furthermore, SSOSH scores are significantly different between those who seek psychological services and those who do not.4

Spanish version of the Stigma Scale for Receiving Psychological Help (SSRPH). It consists of 5 items and has 4 response categories: 0, strongly disagree; 1, disagree; 2, agree; and 3, strongly agree. High scores indicate a greater perception of public stigma. Adequate internal consistency has been reported (Cronbach's alpha, 0.72–0.76).4,25,33 The instrument was translated and adapted for Colombia by our research group and demonstrated a Cronbach's alpha of 0.72 (work not yet published).

Spanish translation of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help - Short Form (ATSPPH-SF) scale It consists of 10 items and 4 Likert-type response options: 3, I disagree; 2, I probably agree; 1, I probably disagree; and 0, I disagree. Higher scores reflect more positive attitudes towards seeking professional help. It was validated in a population of Spanish speakers in the United States and has good internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha, 0.80–0.84).4,21,34

Spanish translation of the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale (MC-SDS). It measures the interest in social approval of the respondent and consists of 33 items that are answered as true or false. A high score indicates interest in social approval. It was validated in Argentina and showed adequate internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha, 0.75–0.84).5

Statistical analysisThe sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are described as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables and as mean ± standard deviation and median [interquartile range] for quantitative variables. The percentage of missing scores and the distribution in the population of the response categories were determined. Floor effect and ceiling effect were considered if more than 15% of the participants reached the minimum or maximum possible score.28

For the structural construct validity, the single factor model proposed by the authors of the original tool and by Acun was evaluated by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the Mplus program using the diagonally weighted least squares estimation method (WLSMV), which is recommended for ordinal variables.4,35–37 The following goodness-of-fit statistics were used: χ2 of the general fit of the model, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) and WRMR (Weighted Root Mean Square Residual). The model was considered acceptable if the χ2 had p > 0.05, RMSEA < 0.08, CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95, and WRMR < 0.90.38

Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha with its respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for the entire scale and it was considered adequate if it showed values between 0.7 and 0.9.39

For the reproducibility of the test, ICC was estimated with its 95% CI and it was considered acceptable if it was >0.7. In addition, the standard error of measurement and the Bland-Altman limits of agreement were calculated.28,40

The construct validity was examined by calculating the Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ); convergent validity with the correlation between the SSOSH scores and those of the ATSPPH-SF (ρ <–0.5 was expected) and the SSRPH (ρ >0.4 was expected); and divergent validity, between the SSOSH and MC-SDS scores (ρ between –0.2 and 0.2 was expected). The cut-off points for the hypotheses were established taking into account the Vogel study.4

For discriminative validity, the groups willing and unwilling to ask for psychological help in case of having a mental health problem were compared, using the Student's t test for independent samples, since the Shapiro-Wilk test showed that the data distribution was normal (p = 0.202). Statistically significant differences were expected between the scores of the groups compared with p = 0.05 and a moderate effect size (Cohen's d = 0.5).32

Statistical analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS® program version 23, except for the structural validity analysis.

ResultsLinguistic and cultural adaptation of the SSOSH scaleThe SRC decided that the Spanish title of the scale would be “Escala de autoestigma por búsqueda de ayuda” (Self-stigma scale for seeking help), since in existing materials it is most common to find the construct denoted in this way.27 In addition, it was established that the acronym ABA should accompany the title of the Spanish version because the acronym SSOSH would be more difficult to read and identify.

The only item that provoked discussion in the SRC was the first one that, in the original English version, was: “I would feel inadequate if I went to a therapist for psychological help”. This was adapted to “Me sentiría incompetente si fuera donde un terapeuta para obtener ayuda psicológica” [“I would feel incompetent if I went to a therapist for psychological help”]. It was taken into account that “incompetent” in English is a synonym for the word “inadequate” and that the translation “Me sentiría inadecuado” [“I would feel inadequate”] would be poorly understood in Colombian Spanish and would not reflect well the meaning of the item.

Pilot testTwenty students participated, mostly male (65%), with an average age of 26.5 ± 2.9 years. They belonged to the programmes in Medicine (60%), Surgical Instrumentation (35%) and Prehospital Care (5%). Completing the scale took an average of 4 min. The participants thought there was a lack of clarity in the instructions, specifically in the phrase “Please use the 5-point scale to rate the degree to which each item describes how you might react in such a situation.” So it was changed to: “Please indicate the degree to which each item describes how you might react in such a situation.” Once the adjustments had been made, the final version of the scale adapted in Spanish was obtained.

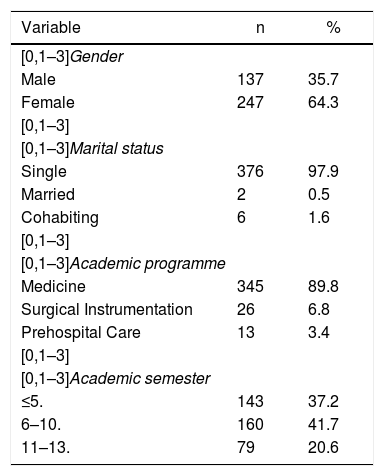

Evaluation of psychometric propertiesParticipantsAlthough the sample calculated for internal consistency and the validity of the structural construct was 320 students, it was possible to include 384: 35.7% men and 64.3% women, aged between 18 and 49 years (median, 21 20,23 years), the majority of whom were single (97.9%) and from the academic programme in Medicine (89.8%) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample (n = 384).

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| [0,1–3]Gender | ||

| Male | 137 | 35.7 |

| Female | 247 | 64.3 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Marital status | ||

| Single | 376 | 97.9 |

| Married | 2 | 0.5 |

| Cohabiting | 6 | 1.6 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Academic programme | ||

| Medicine | 345 | 89.8 |

| Surgical Instrumentation | 26 | 6.8 |

| Prehospital Care | 13 | 3.4 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Academic semester | ||

| ≤5. | 143 | 37.2 |

| 6–10. | 160 | 41.7 |

| 11–13. | 79 | 20.6 |

The proportion of students who agreed to participate in the study was equivalent to 18.3%. Those who did not participate were 50.5% men, aged between 16 and 62 years old (median, 22 20,24 years). Of the total, 45.4% were in the first 5 semesters; 29.9%, between the 6th and 10th semester, and 24.7% between the 10th and 13th semester. Their distribution in the academic programmes was: Medicine, 80.3%; Surgical Instrumentation, 14%; and Prehospital Care, 5.7%. Differences were found between the students who agreed to participate in the present study and those who did not in terms of sex (χ2 = 27.5; df = 1; p < 0.001), academic programme (χ2 = 20.8; df = 2; p < 0.001), academic semester (χ2 = 20.6; df = 2; p < 0.001) and age (Mann-Whitney U, p = 0.046).

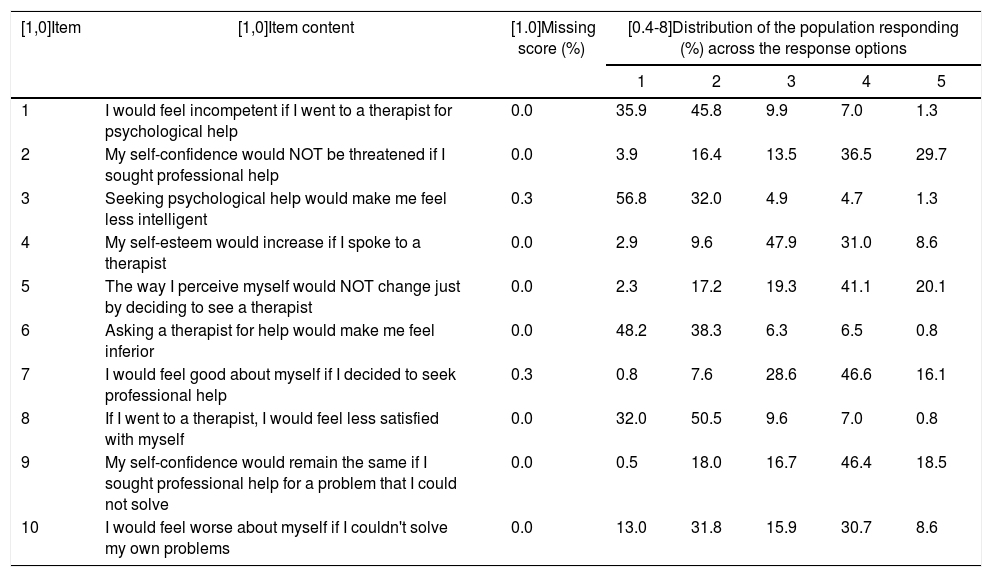

Description of the itemsThe items with some percentage of missing scores were item 3 (0.3%) and item 7 (0.3%). All the response options were used and no homogeneity was detected in the percentage distribution of the population in the response categories in any of the items (Table 2). Regarding the distribution of the scale scores in the sample, 1.3% of the participants obtained the minimum score and no participant obtained the maximum. The median of the total scores was 22 18,25 points. The minimum score obtained was 10 and the maximum, 40.

Missing scores and distribution in the population of the response categories for each item (n = 384).

| [1,0]Item | [1,0]Item content | [1.0]Missing score (%) | [0.4-8]Distribution of the population responding (%) across the response options | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

| 1 | I would feel incompetent if I went to a therapist for psychological help | 0.0 | 35.9 | 45.8 | 9.9 | 7.0 | 1.3 |

| 2 | My self-confidence would NOT be threatened if I sought professional help | 0.0 | 3.9 | 16.4 | 13.5 | 36.5 | 29.7 |

| 3 | Seeking psychological help would make me feel less intelligent | 0.3 | 56.8 | 32.0 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 1.3 |

| 4 | My self-esteem would increase if I spoke to a therapist | 0.0 | 2.9 | 9.6 | 47.9 | 31.0 | 8.6 |

| 5 | The way I perceive myself would NOT change just by deciding to see a therapist | 0.0 | 2.3 | 17.2 | 19.3 | 41.1 | 20.1 |

| 6 | Asking a therapist for help would make me feel inferior | 0.0 | 48.2 | 38.3 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 0.8 |

| 7 | I would feel good about myself if I decided to seek professional help | 0.3 | 0.8 | 7.6 | 28.6 | 46.6 | 16.1 |

| 8 | If I went to a therapist, I would feel less satisfied with myself | 0.0 | 32.0 | 50.5 | 9.6 | 7.0 | 0.8 |

| 9 | My self-confidence would remain the same if I sought professional help for a problem that I could not solve | 0.0 | 0.5 | 18.0 | 16.7 | 46.4 | 18.5 |

| 10 | I would feel worse about myself if I couldn't solve my own problems | 0.0 | 13.0 | 31.8 | 15.9 | 30.7 | 8.6 |

1: strongly disagree; 2: disagree; 3: neither agree nor disagree; 4: agree; 5: strongly agree.

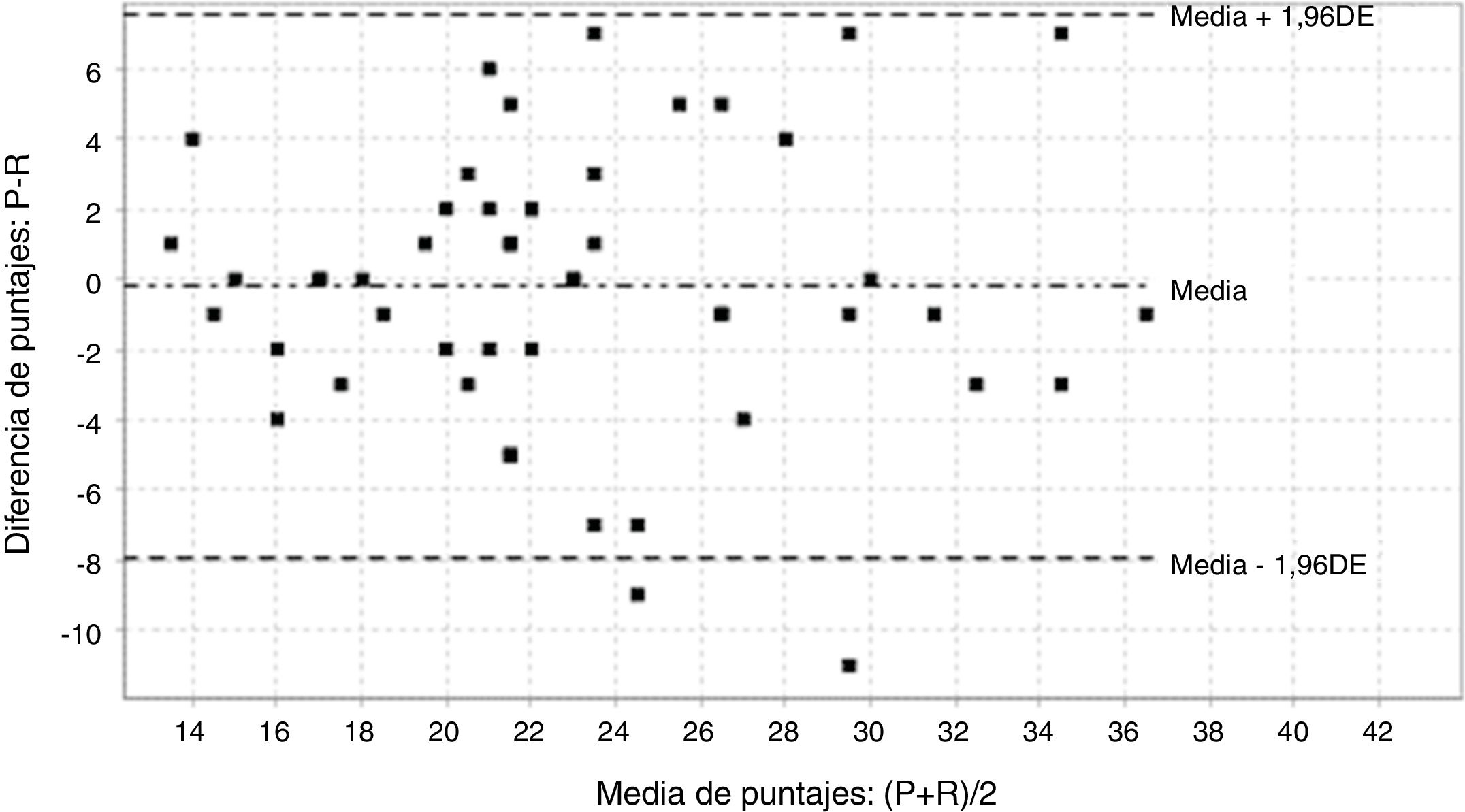

Internal consistency was adequate, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.77–0.83). All item-total correlations were above 0.3, except item 4, the correlation of which was 0.2. Regarding the test-retest reproducibility, the ICC was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.63–0.86) and the standard error of measurement was 2.7 points. The mean of the differences in scores between measurements was –0.2 points and the Bland-Altman limits of agreement were between –7.959 and 7.559 points (Fig. 1).

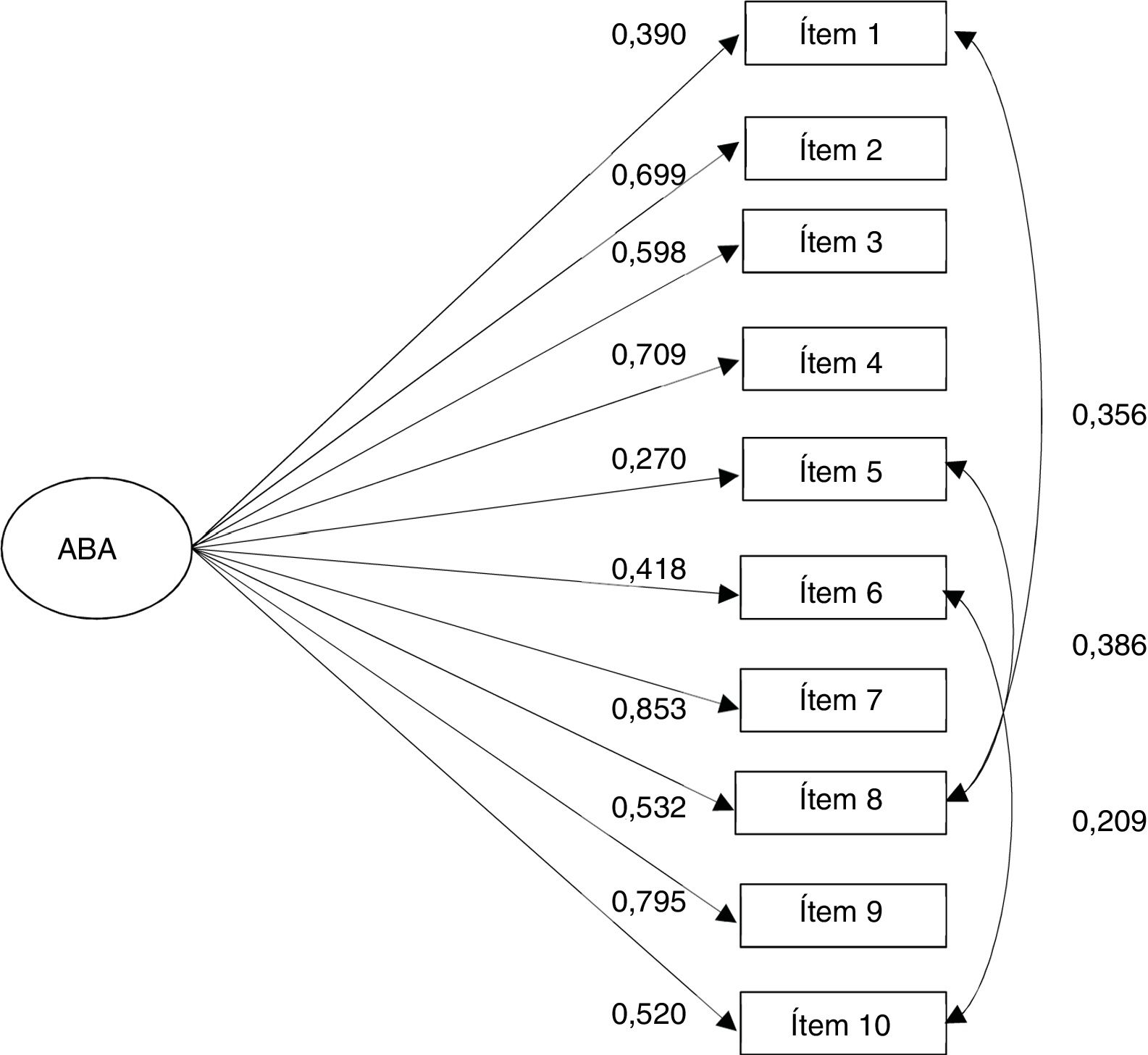

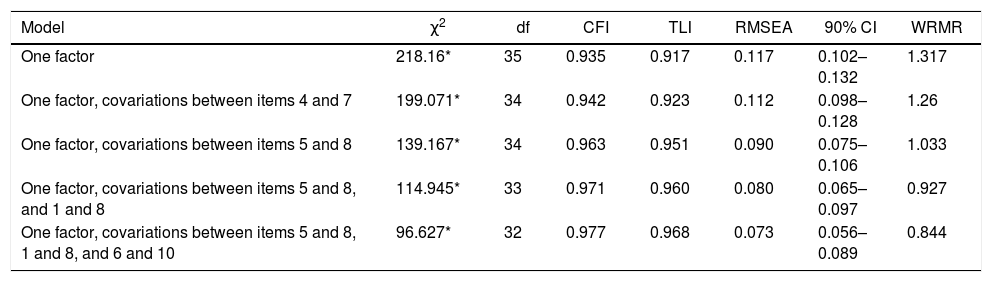

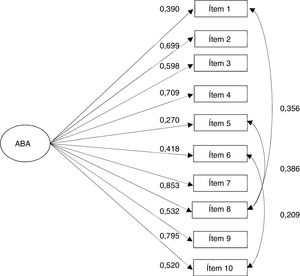

Construct validityFor the evaluation of structural validity, cases with missing values (0.5%) were excluded. Initially, the goodness-of-fit of 5 one-dimensional models was evaluated. The first was the one proposed by Vogel et al.4 and the second was the one proposed by Acun37, in which the covariations between items 4 and 7 were included. Since the first model did not show an adequate fit, the modification indices were revised and three additional models were tested that included the covariations of items 5 and 8 (model 3), 5 and 8, and 1 and 8 (model 4) and 5 and 8, 1 and 8, and 6 and 10 (model 5) (Table 3). Finally, model 5 showed the best fit: χ2 = 96.627; p < 0.0001; RMSEA = 0.073 (90% CI, 0.056-0.089); CFI = 0.968; TLI = 0.977 and WRMR = 0.844 (Fig. 2).

Indicators of goodness-of-fit of confirmatory factor analysis.

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | 90% CI | WRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One factor | 218.16* | 35 | 0.935 | 0.917 | 0.117 | 0.102– 0.132 | 1.317 |

| One factor, covariations between items 4 and 7 | 199.071* | 34 | 0.942 | 0.923 | 0.112 | 0.098–0.128 | 1.26 |

| One factor, covariations between items 5 and 8 | 139.167* | 34 | 0.963 | 0.951 | 0.090 | 0.075–0.106 | 1.033 |

| One factor, covariations between items 5 and 8, and 1 and 8 | 114.945* | 33 | 0.971 | 0.960 | 0.080 | 0.065–0.097 | 0.927 |

| One factor, covariations between items 5 and 8, 1 and 8, and 6 and 10 | 96.627* | 32 | 0.977 | 0.968 | 0.073 | 0.056–0.089 | 0.844 |

CFI: Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index; WRMR: Weighted Root Mean Square Residual.

The scale showed convergent validity because its scores correlated positively with the SSRPH (ρ = 0.39; p < 0.001) and negatively with the ATSPPH-SF (ρ = –0.50; p < 0.001). Furthermore, the SSOSH scale scores were found to have a low and non-significant correlation with the MC-SDS (ρ = –0.05; p = 0.323), which was evidence of divergent validity.

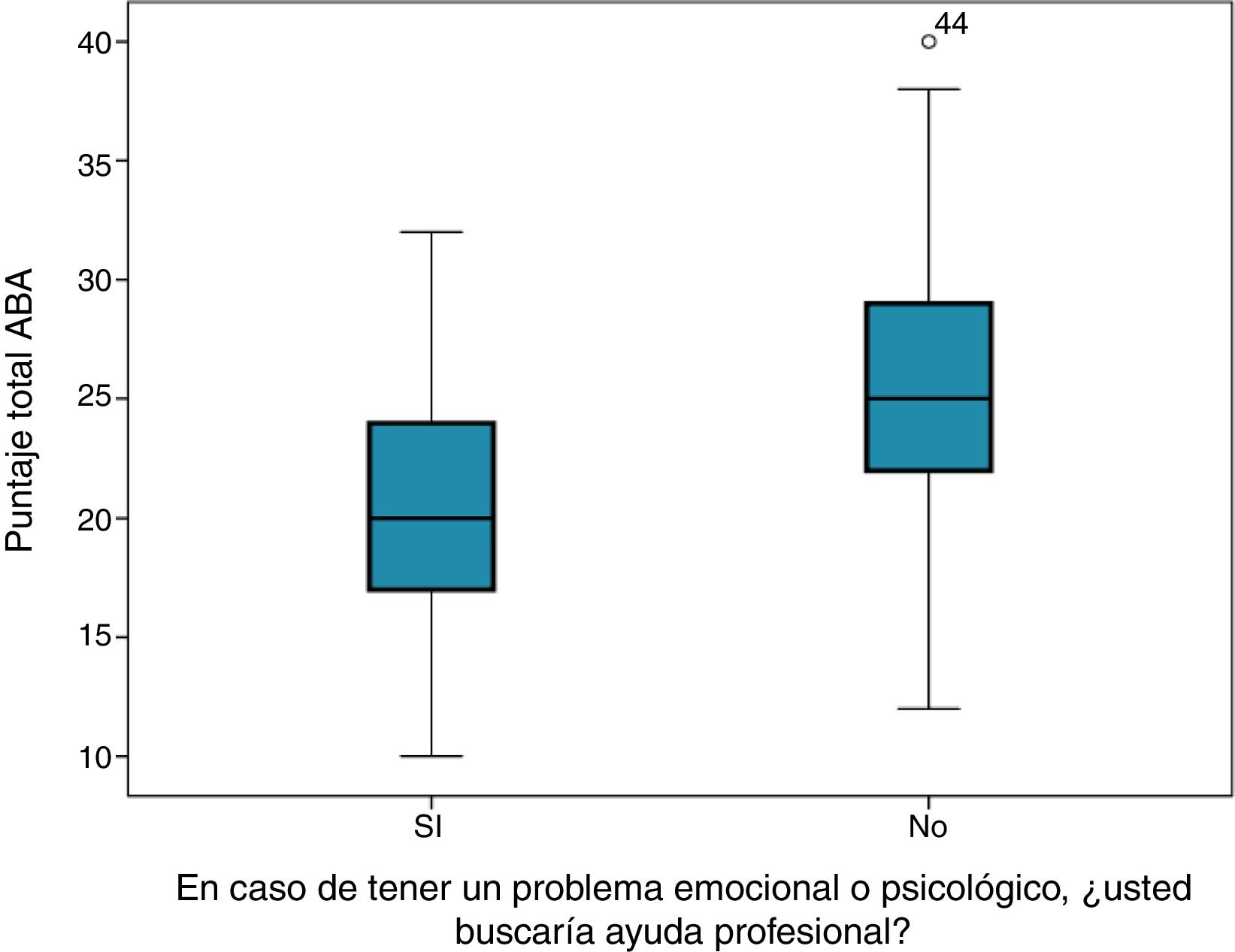

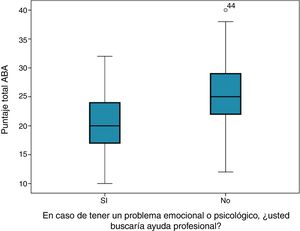

Regarding discriminative validity, differences were observed in the mean SSOSH scores between those with and without a positive disposition towards seeking help (Student's t = 5.067; p < 0.001). The group with a positive disposition had a mean of 20.7 ± 5.4 points, while in those with a negative disposition it was 25.6 ± 5.9 (mean difference, 4.9; 95% CI, 2.99–6.83; d = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.51–1.21) (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThis study evaluated the validity and reliability of the SSOSH scale for its use in Colombia. The SSOSH scale measures the psychological impact of internalising a stigma associated with seeking professional mental health treatment in university populations. It is a short and quick-to-complete scale that, when validated, will contribute to research and the generation of evidence-based interventions.41

In general, the results of the evaluation of psychometric properties were satisfactory. The description of the scores in the items showed a percentage of losses <3% in all items, which is acceptable and indicates that they were understandable and relevant for almost the entire sample. The distribution of scores in the response categories showed that all response options were informative and had discriminative qualities. Furthermore, no floor or ceiling effect was found in the distribution of scores.

The internal consistency of the SSOSH scale indicates a high degree of interrelation between the items and the homogeneity of the measurement. The Cronbach's alpha found was close to that reported by previous studies.4,33,36,42,43 However, it differs from the Cronbach's alpha of 0.71 reported by Acun.37 This is probably due to the use of a smaller number of items by this author, which is known to decrease the value of Cronbach's alpha.28 In this case, Acun used only 9 of the 10 definitive items of the SSOSH in English, arguing a low factor loading of item 10.

The results of the test-retest reproducibility analysis indicate that the scale scores in the sample are stable over time. We can trust that 77% of the total variance between measurements corresponds to true differences in the scores obtained from the participants, and the remaining variability can be attributed to measurement errors. The ICC calculated was similar to that found in the validation study of the scale in the United States (0.72).4 Moreover, a standard error of measurement of 2.7 points is acceptable, showing a very favourable degree of precision when compared with the range of scores that goes from 10 to 50 points. In the Blant-Altman limits of agreement, there were no systematic measurement errors between the applications, which provides more evidence on the reliability of the scores.

The CFA made it possible to establish that the data collected in the empirical sample in Colombia fit well the one-dimensional theoretical model proposed by the developers of the scale. Unlike previous studies that performed a CFA with the maximum likelihood method4,36, the present study used the diagonally weighted least squares (WLSMV) method to estimate the goodness-of-fit statistics, as it is considered more robust and appropriate for the SSOSH scale, which has items with an ordinal measurement level.35 Meanwhile, the CFA modification indices led to the examination of Model 5, which presented the best fit, showing covariation between items 5 and 8, 1 and 8, and 6 and 10. These covariances may be due to the similarity in the wording of the contents of the items. It should be added that our result contrasts with what was found in a validation study of the scale in Turkey, where they observed that the model was two-dimensional.44 However, it was not the same scale because they used the version with 23 items that came from the original scale construction study.

Regarding the convergent construct validity, it was expected that those who are more susceptible to perceptions of public stigma for receiving psychological help would tend to internalise the stigma.45,46 The moderate positive correlation with a public stigma scale favours the validity of the SSOSH. In the validation study of the scale in the United States, a moderate and positive correlation was also reported between these two constructs in two different samples (ρ = 0.48 and ρ = 0.46).4 The moderate negative correlation of the SSOSH with the measure of attitudes towards seeking help―that is, the greater the experience of self-stigma, the more negative attitudes towards seeking help in mental health would be produced―is also in favour of validity. This finding is consistent with the existing theory that the search for psychological treatment requires that individuals feel sympathy for themselves and feel worthy of receiving help.47 The internalisation of stigma erodes the individual's self-esteem, which leads to less sympathy for themselves and more negative attitudes about seeking help.33 This is in line with the original validation of the scale, in which moderate negative correlations were observed between the SSOSH and the ATSPPH-SF in two samples (ρ = –0.53 and ρ = –0.63).4

The lack of significant association with the measure of social desirability supports the notion that the self-stigma of seeking help scale measures the internalisation of the stigma of seeking psychological help, and not the social benefit of the individual's reactions to possible scenarios of mental health problems and help-seeking behaviour. In the study, the self-stigma measure was not correlated with the social desirability scale, which supports the divergent-type construct validity of the scale. Validation of the original scale reported a non-significant negative correlation of –0.13 between these two measures.4

The differences found with a high effect size between those who view the intention to seek help in case of suffering a mental health problem positively and those who do not support the discriminative validity of the scale scores, that is, the ability to distinguish through the scores between relevant groups with respect to the construct. Those who had a negative disposition towards seeking help obtained the highest scores on the measure of self-stigma. However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as it is most likely that at the time of the evaluation the majority of the participants did not have significant mental health problems. Therefore, the reported willingness to seek help may not be a reliable predictor of actually consulting a professional when needed.

Some of the limitations of this study have to do with the self-selection of the participants in the sample, since the variability of the sample could be different than in the target population and this would affect the reliability observed.29

Another limitation is that the ATSPPH-SF and MC-SDS scales, used for the evaluation of convergent and divergent validity, are not validated in Colombia. However, the Spanish versions of these instruments were used, which were validated in Spanish-speaking populations of university students in the United States and Argentina, where they showed adequate psychometric properties.34,48 The decision to use the aforementioned instruments is due to the need to obtain new information about the consistency between the SSOSH scale scores and the conceptual model of the construct. Although this information was not obtained under ideal conditions, it is a starting point for further refinements of the evidence provided, taking into account the continuous nature of the validation processes.

It is important to bear in mind that this validation of the SSOSH was performed in students of health sciences programmes and it might be thought that the psychometric properties cannot be generalised to other university student populations. This has been considered because it can be assumed that they would have greater homogeneity in the self-stigma for seeking help construct as they are sensitised to mental health problems and therefore have less tendency to stigmatise both the condition and the search for treatment. However, the opposite could also be expected: people who are being trained to help others may self-stigmatise if they themselves seek care because they believe, for example, that they should be able to solve their problems on their own, and that their aptitude would be called into question, etc.17,49 In addition, there is evidence that medical students with MDs have little access to mental health services offered at universities and that approximately one third do not seek help, because they believe it would signify weakness and are concerned about the impact this fact would have on their professional career.19 Therefore, we are not certain that this is a population whose homogeneity is so high that the psychometric properties are significantly altered. Moreover, the generalisation of the measure for other non-university populations is a limitation, since the psychometric properties of the scale scores are unknown in populations with different levels of education, income or severity of the mental health problem.

Future research needs to carry out the process of evaluating the sensitivity to change of the measure's scores. The discriminative capacity of the scale should also be examined between groups that have actually sought professional help in the past and those who have not, or better still, through prospective monitoring of this behaviour. In addition, in the future, studies will be carried out that evaluate differences in the functioning of the items and other psychometric properties between populations from different faculties and university programmes.

ConclusionsThe SSOSH scale is a useful, valid and reliable measure to investigate help-seeking self-stigma in university populations in the area of health in Colombia. Although greater knowledge of its sensitivity to change and its psychometric properties in different contexts is required, it can be used to measure this construct as an initial step in the study of the search for and access to mental health services in university students.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare in relation to the research topic.

To the University Welfare Office of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Antioquia, as well as to the undergraduate students who participated in the present study.

Please cite this article as: Larrahondo BF, Valencia JG, Martínez-Villalba AMR, Ospina JPZ, Aguirre-Acevedo DC. Validación de la escala de Autoestigma por Búsqueda de Ayuda (ABA) en una población de estudiantes de Medicina de Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:82–91.

This article is part of an academic thesis to obtain the title of Master in Mental Health from the University of Antioquia.