Mental disorders are very prevalent in the general population. Despite this, it is estimated that only about a third of the people affected is able to recognise problems on their own and to access health services. The aim was to determine the factors associated with the lack of self-recognition of mental problems and disorders in the Colombian population.

MethodsThe National Mental Health Survey (ENSM-2015) conducted in Colombia identified adults over 18 years that answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Have you had a mental problem or disorder?’, had a positive score in mental disorders measured by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) 3.0, or in mental problems detected by the SRQ-20. A bivariate analysis, as well as a logistic regression, were performed with possible related variables.

ResultsA sample of 10, 870 adults was obtained, of whom 12.25% (1332) had mental disorders and 30.2% (3282) had mental problems. Of those individuals with disorders and problems, 7.9% recognised themselves as affected. The variables associated with self-recognition of disorders or problems were, among others: being female (OR = 1.8; 95%CI, 1.4−2.3), family dysfunction (OR = 1.5; 95%CI, 1.2−2.0), to have experienced a traumatic event (OR = 1.8; 95%CI, 1.4−2.2), illegal substance consumption (OR = 0.5; 95%CI, 0.4−0.7), not being poor (OR = 1.9; 95%CI, 1.2−3.0), and not having chronic illnesses (OR = 1.6; 95%CI, 1.3−2.1).

ConclusionsSelf-recognition is of great relevance to improve access to care by adults. The results provide associated variables that allow planning interventions that can promote the recognition of mental problems or disorders in this population.

Los trastornos mentales son muy prevalentes en la población general; a pesar de ello, solo alrededor de un tercio reconoce que los tiene y accede a los servicios de salud. El objetivo es determinar los potenciales factores asociados con la falta de autorreconocimiento de trastornos y problemas mentales entre la población colombiana.

MétodosEn la Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental 2015 (ENSM 2015) realizada en Colombia, se recogieron las respuestas de los adultos mayores de 18 años a la pregunta sobre si tenían algún problema o trastorno mental que hayan puntuado positivo en trastornos mentales medidos por el CIDI 3.0 o en problemas mentales detectados por el SRQ-20. Se realizó un análisis bivariable con posibles variables relacionadas y otro multivariable de regresión logística.

ResultadosSe obtuvo una muestra de 10.870 adultos; el 12,25% (1.332) sufría trastornos y el 30,2% (3.282), problemas. Del total de personas con trastornos y problemas, el 7,9% se autorreconoció con ellos. Las variables asociadas con el autorreconocimiento de trastornos o problemas fueron: ser mujer (OR = 1,8; IC95%, 1,4-2,3), tener disfunción familiar (OR = 1,5; IC95%, 1,2-2,0), haber sufrido un evento traumático (OR = 1,8; IC95%, 1,4-2,2), consumir sustancias psicoactivas (OR = 0,5; IC95%, 0,4-0,7), no ser pobre (OR = 1,9; IC95%, 1,2-3,0) y no tener enfermedades crónicas (OR = 1,6; IC95%, 1,3-2,1), entre otras variables asociadas.

ConclusionesEl autorreconocimiento de los adultos es de gran relevancia para iniciar el acceso a la atención. Los resultados proveen variables asociadas que permiten planear intervenciones para promover el autorreconocimiento en esta población.

Mental illnesses have had prevalences in the adult population ranging between 5% and 26% in the last year, regardless of the country or region of the world in which they are studied, and the burden and consequences of these diseases affect the quality of life of those who suffer them.1 In studies on the burden of disease in the world, it has been seen that mental diseases, especially depressive and anxiety spectrum disorders, as well as those derived from alcohol consumption, are among the leading causes of disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) loss in the vast majority of the world's countries.2

Despite this impact, there is a clear gap in mental health care and access to it with respect to other chronic non-communicable diseases, with deficiencies in the availability and supply of resources that can meet the demands of these disorders.3,4 The identification of these deficiencies has had an impact on the formulation and establishment of mental health care in different countries,5–7 but the implementation of these policies has not succeeded in causing an increase in the care and recognition of patients suffering from these diseases. On the contrary, there is still a percentage of citizens who do not access health services, resulting in a delay in their care, and sometimes priority is given to the most serious cases or those with more catastrophic events (suicide attempt, traffic accident, hetero-aggressive event).1,8,9

In the context of mental illnesses, the process of access to health confirms and demonstrates the complexity of its dynamics, since it is not limited exclusively to the existence and availability of resources, but there are other variables and other actors (users, health professionals, the state) that must be taken into account to ensure that those who suffer from them have access to mental health.10,11 In various studies around the world,12,13 it has been found that the main obstacle cited by patients with mental illnesses is what has been grouped under the category of attitudinal barriers, the vast majority of which are specific to each individual and are created in the social, cultural and political contexts of each person. This can affect their recognition of mental illness, awareness of the need for care and subsequent access to this service.

These attitudinal barriers may be related to various factors that are part of the interaction and dynamics of the process of access to health, so their identification has been a starting point to intervene in them and thus increase the proportion of patients who access mental health services.14 In several of the studies, variables such as the desire to self-manage the disease, knowledge or literacy in mental health, prejudices or ideas related to stigmatisation processes and social or cultural constructs have been identified. Among these is support found in family, religion or other behaviours, which have been identified as issues that are grouped in the so-called attitudinal barriers, which limit the recognition of mental illness and subsequent access to health services.15–19 Another factor has to do with self-recognition of the state of health, which, in addition to its relationship with the aforementioned variables, can be linked to awareness of the mental state and the consequent need to seek consultation.

Identification of the main causes of attitudinal barriers is necessary in each country and territory, as they may vary according to the constructs or ideas of each culture. With regard to the Colombian population, in the latest mental health survey (ENSM 2015), the percentages of attention and self-recognition were investigated among those interviewed over 18 years of age with some type of mental health problem in the last 12 months. In the group of young adults (18–45 years old; n = 5889), 36.5% had a problem in the established period, and of these only 38.5% recognised the problem and sought some type of health care for this reason. When exploring the reasons of those who had not sought care, it was found that the most common reasons were: not considering it necessary (47%), neglecting their health (24%) and not wanting to do so (16%). In the group of adults over 45 years of age (n = 4981), 76% did not seek some type of mental health care, and the reason cited for not seeking care was neglect (24%).20

Given the gap in and poor recognition of mental problems in the Colombian population, and also the reality that for the adult population the main reasons for not accessing health services are secondary to attitudinal causes, the aim of this study is to make it possible to identify the variables related to a greater or lesser self-recognition of mental illness, and especially to inquire about the variables associated with the lack of self-recognition of mental illness and problems. This could indicate new forms of intervention to achieve better access for these people who, because they do not recognise themselves as ill, never seek care for these reasons.

MethodsThe ENSM 2015 is a cross-sectional study with a sample representative of the country, in which individuals of all age groups were included, and adults were defined as those over 18 years of age. This survey included the collection of a large number of sociodemographic variables, history of violent events, trust in third parties, presence of mental health disorders or problems, and consumption of psychoactive substances or alcohol, using various duly validated instruments. For further information on the instruments used in the study, the documents and articles related to the ENSM can be consulted.20–22

In the ENSM, the Colombian population was asked explicit and tailored questions about whether they had suffered any problem or mental illness in the last 12 months. Likewise, the presence or absence of mental health problems or disorders was confirmed using previously validated instruments, such as the 20-item self-reporting questionnaire (SRQ-20), in the case of mental health problems, and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview version 3.0 computer-assisted personal interview (CIDI-CAPI 3.0) diagnostic questionnaire for mental disorders.1,22–24

From this data, variables associated with recognition of mental illness in adults were investigated, including sociodemographic variables, perception of the working environment, feelings of discrimination, support from third parties, use of psychoactive substances, socioeconomic variables and family dysfunction. The self-recognition reported by the participants was compared with the presence of a mental disorder defined by the CIDI 3.0, and the identified mental health problems, with the SRQ-20. The assessment of household poverty was calculated with the multidimensional poverty index (MPI).

Firstly, as part of the analysis, the percentage distribution of individuals across the categories of each nominal and ordinal variable was observed, with some of these being found to have low frequencies. To obtain better results in the bivariate analyses and the proposed logistic model, a recategorisation was done, taking into account the clinical importance of certain variables. The continuous variables were also categorised into clinically relevant risk groups, and the variables were constructed to study a chronic disease, feeling of discrimination, participation in groups and trust in third parties, from the responses of the ENSM.

After categorising the variables, bivariate models were performed with each of the cited variables with respect to the variable of interest (self-recognition of a mental problem or disorder). From these bivariate models, variables with p < 0.20 were selected to form a multivariate model. The final selection of the variables in the multivariate logistic regression model was performed using the stepwise method. In each of the models, the indirect relative risk is presented as an association measure, as an odds ratio (OR) with its standard error and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). The data were processed using the program STATA version 14.

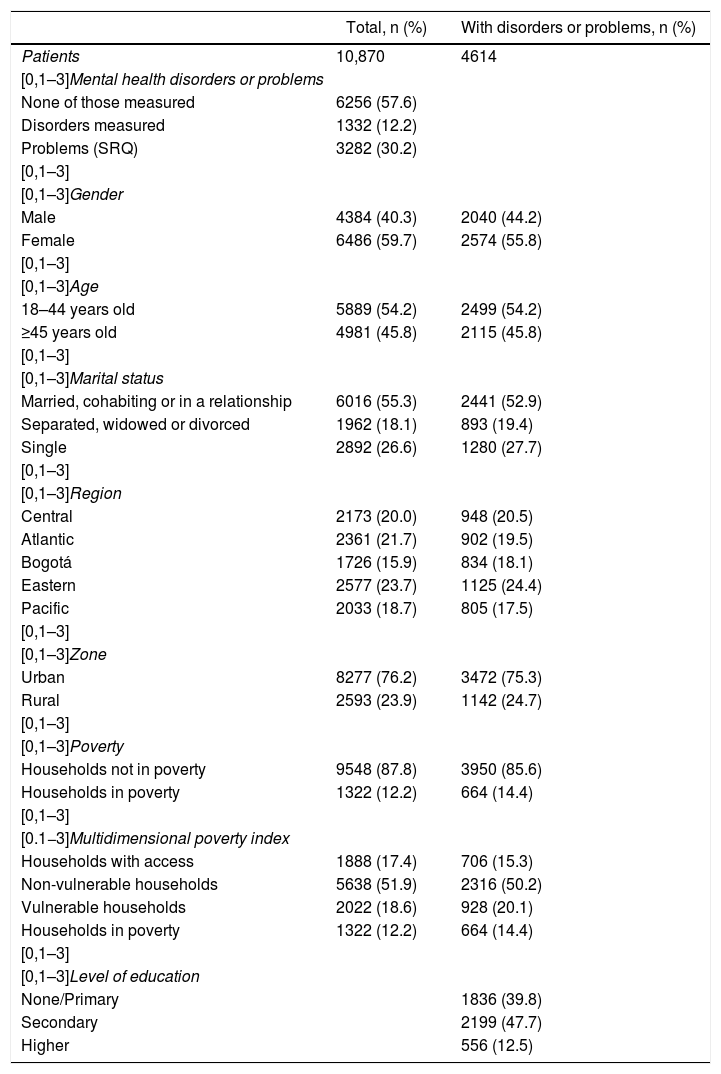

ResultsBelow are given the sociodemographic data of the entire country-wide sample and the sample of people with a mental disorder (affective disorders: depression and bipolar disorder, or anxiety disorders: generalised anxiety, panic and social phobia), alcohol abuse or dependence and mental problems, according to the SRQ-20. In the total sample, 4614 people (32.4%) presented some disorder (of those measured) or mental problem according to the SRQ-20 (Table 1).

Description of the total sample and of those with mental disorders or problems.

| Total, n (%) | With disorders or problems, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | 10,870 | 4614 |

| [0,1–3]Mental health disorders or problems | ||

| None of those measured | 6256 (57.6) | |

| Disorders measured | 1332 (12.2) | |

| Problems (SRQ) | 3282 (30.2) | |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Gender | ||

| Male | 4384 (40.3) | 2040 (44.2) |

| Female | 6486 (59.7) | 2574 (55.8) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Age | ||

| 18–44 years old | 5889 (54.2) | 2499 (54.2) |

| ≥45 years old | 4981 (45.8) | 2115 (45.8) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Marital status | ||

| Married, cohabiting or in a relationship | 6016 (55.3) | 2441 (52.9) |

| Separated, widowed or divorced | 1962 (18.1) | 893 (19.4) |

| Single | 2892 (26.6) | 1280 (27.7) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Region | ||

| Central | 2173 (20.0) | 948 (20.5) |

| Atlantic | 2361 (21.7) | 902 (19.5) |

| Bogotá | 1726 (15.9) | 834 (18.1) |

| Eastern | 2577 (23.7) | 1125 (24.4) |

| Pacific | 2033 (18.7) | 805 (17.5) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Zone | ||

| Urban | 8277 (76.2) | 3472 (75.3) |

| Rural | 2593 (23.9) | 1142 (24.7) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Poverty | ||

| Households not in poverty | 9548 (87.8) | 3950 (85.6) |

| Households in poverty | 1322 (12.2) | 664 (14.4) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0.1−3]Multidimensional poverty index | ||

| Households with access | 1888 (17.4) | 706 (15.3) |

| Non-vulnerable households | 5638 (51.9) | 2316 (50.2) |

| Vulnerable households | 2022 (18.6) | 928 (20.1) |

| Households in poverty | 1322 (12.2) | 664 (14.4) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Level of education | ||

| None/Primary | 1836 (39.8) | |

| Secondary | 2199 (47.7) | |

| Higher | 556 (12.5) | |

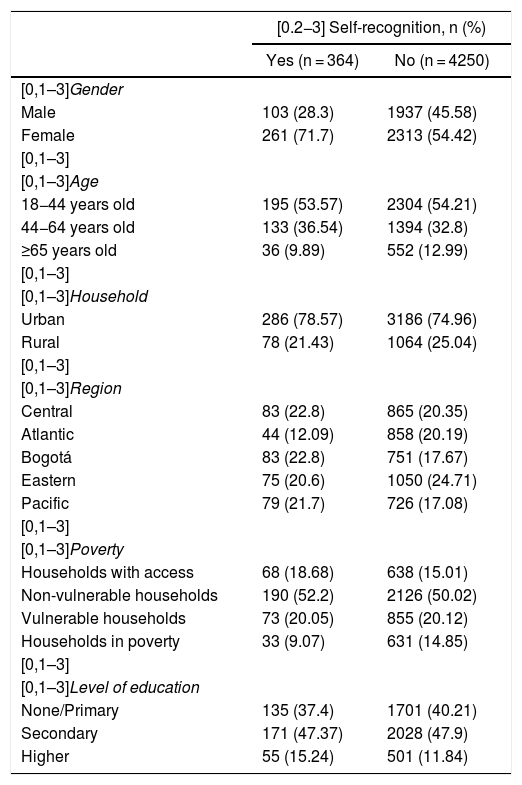

Of the people with some type of disorder or problem, 7.9% (n = 364) recognise their mental difficulty, while 92.3% (n = 4250) do not recognise it (Table 2).

Characteristics of people who self-recognise with mental disorders or problems.

| [0.2−3] Self-recognition, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Yes (n = 364) | No (n = 4250) | |

| [0,1–3]Gender | ||

| Male | 103 (28.3) | 1937 (45.58) |

| Female | 261 (71.7) | 2313 (54.42) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Age | ||

| 18−44 years old | 195 (53.57) | 2304 (54.21) |

| 44−64 years old | 133 (36.54) | 1394 (32.8) |

| ≥65 years old | 36 (9.89) | 552 (12.99) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Household | ||

| Urban | 286 (78.57) | 3186 (74.96) |

| Rural | 78 (21.43) | 1064 (25.04) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Region | ||

| Central | 83 (22.8) | 865 (20.35) |

| Atlantic | 44 (12.09) | 858 (20.19) |

| Bogotá | 83 (22.8) | 751 (17.67) |

| Eastern | 75 (20.6) | 1050 (24.71) |

| Pacific | 79 (21.7) | 726 (17.08) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Poverty | ||

| Households with access | 68 (18.68) | 638 (15.01) |

| Non-vulnerable households | 190 (52.2) | 2126 (50.02) |

| Vulnerable households | 73 (20.05) | 855 (20.12) |

| Households in poverty | 33 (9.07) | 631 (14.85) |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Level of education | ||

| None/Primary | 135 (37.4) | 1701 (40.21) |

| Secondary | 171 (47.37) | 2028 (47.9) |

| Higher | 55 (15.24) | 501 (11.84) |

In the bivariate analysis of mental disorders, it is observed that women and Roma people are more likely to recognise their disorders than people in other groups (Table 3). The distribution for problems in adults is similar to that for disorders. Among women and in households not in poverty or in a higher state of poverty, there is greater self-recognition of problems. The other variables have the same tendency.

Self-recognition of mental disorder: bivariate analysis.

| [0,2–4]Self-recognition of disorders | [0,5–7]Self-recognition of problems | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| [0,1–7]Gender | ||||||

| Male | 42 (32.1) | 661 (55) | 15.7 (11.5−21.5) | 61 (26.2) | 1276 (41.9) | 1 |

| Female | 89 (67.9) | 540 (45) | 0.4 (0.3−0.6) | 172 (73.8) | 1773 (58.2) | 2.0 (1.5−2.7) |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Age | ||||||

| 18−44 years old | 87 (66.4) | 815 (67.9) | 9.4 (7.5−11.7) | 108 (46.4) | 1489 (48.8) | 1 |

| 45−64 years old | 39 (29.8) | 314 (26.1) | 0.9 (0.6−1.3) | 94 (40.3) | 1080 (35.4) | 1.2 (0.9−1.6) |

| ≥65 years old | 5 (3.8) | 72 (6) | 1.5 (0.6−3.9) | 31 (13.3) | 480 (15.7) | 0.9 (0.6−1.3) |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Household | ||||||

| Urban | 110 (84) | 959 (79.9) | 8.7 (7.2−10.6) | 176 (75.5) | 2227 (73.0) | 1 |

| Rural | 21 (16) | 242 (20.1) | 1.3 (0.8−2.2) | 57 (24.45) | 822 (27.0) | 0.9 (0.6−1.2) |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Region | ||||||

| Central | 24 (18.3) | 221 (18.4) | 9.2 (6.0−14.0) | 59 (25.3) | 644 (21.1) | 1 |

| Atlantic | 18 (13.7) | 220 (18.3) | 1.3 (0.7−2.5) | 26 (11.12) | 638 (20.9) | 0.4 (0.3−0.7) |

| Bogotá | 31 (23.7) | 273 (22.7) | 1 (0.5−1.7) | 52 (22.3) | 478 (15.69) | 1.2 (0.8−1.8) |

| Eastern | 25 (19.1) | 312 (26) | 1.4 (0.8−2.4) | 50 (21.5) | 738 (24.2) | 0.7 (0.5−1.1) |

| Pacific | 33 (25.2) | 175 (14.6) | 0.6 (0.3−1.0) | 46 (19.7) | 551 (18.1) | 0.9 (0.6−1.4) |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Poverty | ||||||

| Households with access | 25 (19.1) | 178 (14.8) | 7.1 (4.7−10.8) | 43 (18.45) | 460 (15.01) | 1 |

| Non-vulnerable households | 63 (48.1) | 604 (50.3) | 1.3 (0.8−2.2) | 127 (54.5) | 1522 (49.9) | 0.9 (0.6−1.3) |

| Vulnerable households | 27 (20.6) | 249 (20.7) | 1.3 (0.7−2.3) | 46 (19.7) | 606 (19.9) | 0.8 (0.5−1.3) |

| Households in poverty | 16 (12.2) | 170 (14.6) | 1.5 (0.8−2.9) | 17 (7.3) 61 (15.1) | 0.4 (0.2−0.7) | |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Ethnicity | ||||||

| Indigenous | 10 (7.6) | 94 (7.8) | 9.4 (4.9−18.0) | 18 (7.7) | 247 (8.1) | 1 |

| Roma | 1 (0.8) | 4 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1−4.9) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.1) | 3.4 (0.4−32.3) |

| Raizal | 1 (0.8) | 9 (0.8) | 1 (0.1−0.8) | 0 | 16 (0.5) | N/A |

| Palenquero | 19 (14.5) | 127 (10.6) | 0.7 (0.3−1.6) | 0 | 1 (0.0) | N/A |

| Black, mixed, of African descent | 19 (8.2) | 287 (9.4) | 0.9 (0.5−1.8) | |||

| None of the above | 100 (76.3) | 967 (80.5) | 1 (0.5−18.4) | 195 (83.7) | 2493 (81.8) | 1.1 (0.7−1.8) |

| [0,1–7] | ||||||

| [0,1–7]Level of education | ||||||

| None/Primary | 43 (33.1) | 383 (32) | 8.9 (6.5−12.2) | 92 (29.8) | 1318 (43.5) | 1 |

| Secondary | 63 (48.5) | 658 (55) | 1.2 (0.8−1.8) | 108 (46.8) | 1370 (45.2) | 1.1 (0.9−1.5) |

| Higher | 24 (18.5) | 156 (13) | 0 (0.4−1.2) | 31 (13.4) | 345 (11.8) | 1.3 (0.8−2.0) |

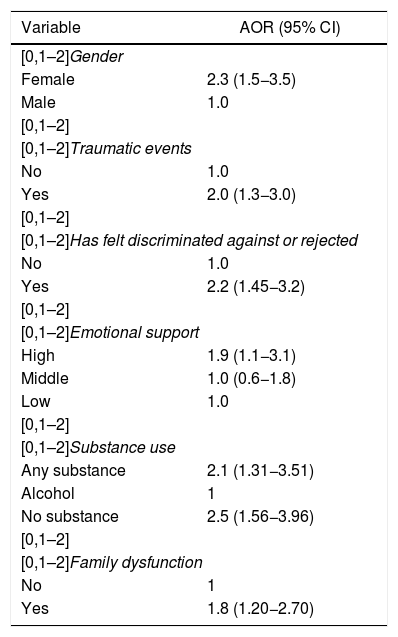

The multivariate analysis (Table 4) shows that being a woman is a factor for a person with a disorder to recognise it, compared to being a man, after controlling for other variables (OR = 2.27). Having suffered a traumatic event is associated with self-recognition, compared with not having suffered one (OR = 2.0). Having felt discriminated against or rejected is a factor associated with recognition of the presented disorder. Having family problems increases self-recognition, as does having greater emotional support. Consumption of substances other than alcohol and not consuming substances increase self-recognition with respect to alcohol consumption, after controlling for other variables.

Regression model adjusted for variables associated with self-recognition of mental disorders.

| Variable | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| [0,1–2]Gender | |

| Female | 2.3 (1.5−3.5) |

| Male | 1.0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Traumatic events | |

| No | 1.0 |

| Yes | 2.0 (1.3−3.0) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Has felt discriminated against or rejected | |

| No | 1.0 |

| Yes | 2.2 (1.45−3.2) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Emotional support | |

| High | 1.9 (1.1−3.1) |

| Middle | 1.0 (0.6−1.8) |

| Low | 1.0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Substance use | |

| Any substance | 2.1 (1.31−3.51) |

| Alcohol | 1 |

| No substance | 2.5 (1.56−3.96) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Family dysfunction | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 1.8 (1.20−2.70) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AOR: adjusted odds ratio.

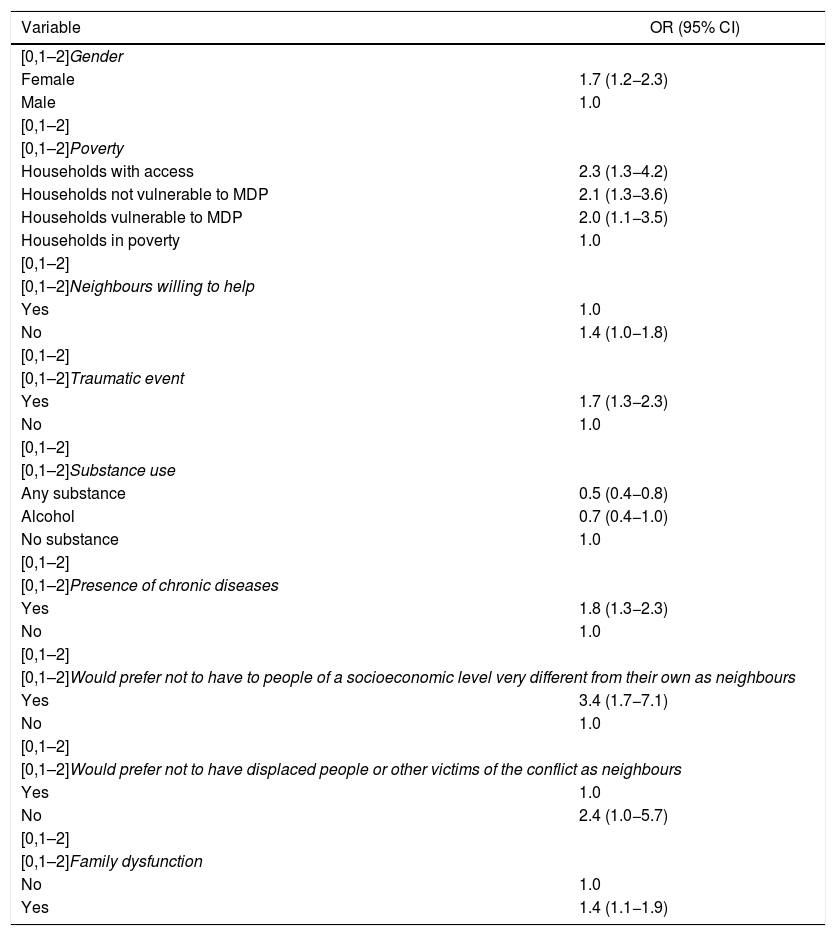

Table 5 shows the variables associated with self-recognition of mental problems. As in the bivariate model, the only sociodemographic variable associated with self-recognition of problems was being a woman (OR = 1.7). Furthermore, in this model it is observed that coming from a household not in poverty (measured by the multidimensional poverty index) entails greater self-recognition, compared to households with less access (OR = 2.3). Not having neighbours willing to help and having experienced traumatic events were associated with greater self-recognition. Consuming substances other than alcohol reduces self-recognition of problems, but dealing with chronic diseases increases self-recognition, among other variables (Table 5).

Regression model adjusted for variables associated with self-recognition of mental problems.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| [0,1–2]Gender | |

| Female | 1.7 (1.2−2.3) |

| Male | 1.0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Poverty | |

| Households with access | 2.3 (1.3−4.2) |

| Households not vulnerable to MDP | 2.1 (1.3−3.6) |

| Households vulnerable to MDP | 2.0 (1.1−3.5) |

| Households in poverty | 1.0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Neighbours willing to help | |

| Yes | 1.0 |

| No | 1.4 (1.0−1.8) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Traumatic event | |

| Yes | 1.7 (1.3−2.3) |

| No | 1.0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Substance use | |

| Any substance | 0.5 (0.4−0.8) |

| Alcohol | 0.7 (0.4−1.0) |

| No substance | 1.0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Presence of chronic diseases | |

| Yes | 1.8 (1.3−2.3) |

| No | 1.0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Would prefer not to have to people of a socioeconomic level very different from their own as neighbours | |

| Yes | 3.4 (1.7−7.1) |

| No | 1.0 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Would prefer not to have displaced people or other victims of the conflict as neighbours | |

| Yes | 1.0 |

| No | 2.4 (1.0−5.7) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Family dysfunction | |

| No | 1.0 |

| Yes | 1.4 (1.1−1.9) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; MDP: multidimensional poverty.

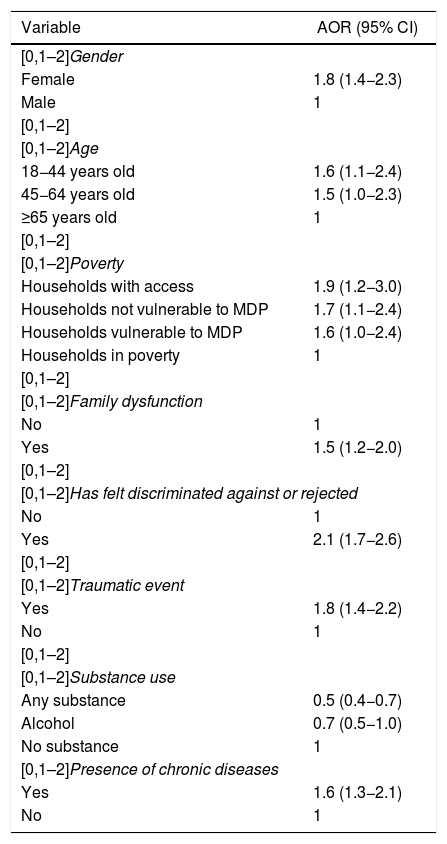

In this last model, problems and disorders are combined, and with this a regression model is carried out in which there is evidence of greater self-recognition among women, people between 18 and 44 years old, those who come from households with greater resources, those who suffer family dysfunction, those who have been discriminated against, those who do not consume substances, those who have experienced traumatic events and those who do not have chronic diseases (Table 6).

Multivariate regression model of self-recognition of disorders or problems (combined) in adults.

| Variable | AOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| [0,1–2]Gender | |

| Female | 1.8 (1.4−2.3) |

| Male | 1 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Age | |

| 18−44 years old | 1.6 (1.1−2.4) |

| 45−64 years old | 1.5 (1.0−2.3) |

| ≥65 years old | 1 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Poverty | |

| Households with access | 1.9 (1.2−3.0) |

| Households not vulnerable to MDP | 1.7 (1.1−2.4) |

| Households vulnerable to MDP | 1.6 (1.0−2.4) |

| Households in poverty | 1 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Family dysfunction | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 1.5 (1.2−2.0) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Has felt discriminated against or rejected | |

| No | 1 |

| Yes | 2.1 (1.7−2.6) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Traumatic event | |

| Yes | 1.8 (1.4−2.2) |

| No | 1 |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Substance use | |

| Any substance | 0.5 (0.4−0.7) |

| Alcohol | 0.7 (0.5−1.0) |

| No substance | 1 |

| [0,1–2]Presence of chronic diseases | |

| Yes | 1.6 (1.3−2.1) |

| No | 1 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; AOR: adjusted odds ratio; MDP: multidimensional poverty.

The ENSM 2015 in Colombia made it possible to establish and identify the prevalence of mental problems and illness, as well as variables that were associated with recognition by the users or respondents themselves. Being female was found to be among the main variables associated with greater self-recognition, both of mental problems and of mental illnesses, which is similar to that found in various studies,25,26 and could be explained by various factors. Among these is the higher prevalence of mental illnesses in women than in men, which could lead them to seek care more frequently, and cultural reasons, such as that women are more fragile or more sensitive to psychological problems, and could go for a mental health consultation without being judged or considered weak, as can happen in the case of men.1,27

When reviewing characteristics related to households, being located in a rural area is usually associated with a lower self-recognition of mental disorders, which can be explained by the difficulties and scarcity of resources related to mental health education, as well as cultural factors specific to each region.28,29 This lower self-recognition in rural areas has been repeatedly documented in several countries, such as Australia30 and Brazil,31 where differences in self-recognition and less use of services and treatments for mental illnesses are evident. This finding, described in other countries, was not found in Colombia, which could be explained by a greater influence of the urban over the rural or greater health education in this area of our country. However, it requires further study.

Being in a good economic situation had some type of association with self-recognition of mental disorders; households with higher incomes and with some vulnerability according to the MPI had a greater association with self-recognition of problems. This finding is consistent with the fact that poverty can have an impact on the appearance and recognition of mental illnesses.32,33 However, this varies between studies and according to the type of instrument used to measure poverty, so it is sometimes reconsidered whether poverty should be evaluated as a whole or broken down into the elements that compose it, such as the state of the dwelling and occupational status.34 Meanwhile, the association between some vulnerability as per the MPI and self-recognition of mental problems is maintained, and it can be proposed that, during the most incipient phase of disorders, the need to access health services tends to be more accepted or there is an awareness of the situation in social strata with some vulnerability, in which it is possible that there has recently been more education in mental health.

Feeling discriminated against for any reason is a factor associated with greater self-recognition of problems and disorders, which could be explained because segregation or rejection leads to mental functioning that is more alert to possible problems, which theoretically could be associated with a greater recognition of some type of psychopathology. In this sense, some groups that may suffer greater discrimination, such as migrants, recognise mental problems more frequently. This was demonstrated in Caplan's study of Latino immigrants, who recognised their own depressive disorder and, at the same time, presented the highest scores on the instrument used to determine perceived stigma.35

Suffering from chronic diseases was also associated with greater self-recognition of mental problems, which is consistent with other findings around the world that the presence of chronic diseases favours greater self-recognition and, therefore, greater access to health services.8,33,36 In our society, there may be greater recognition of other somatic diseases at the expense of mental problems, which are possibly less stigmatised than physical ones. Similar to what happened with the discrimination process, it is known that suffering from a chronic disease can be associated with a greater burden or stress, which can be evidenced as a process of mental illness that is better accepted, due to being motivated by a somatic illness. On the other hand, there may be a bias, since those who suffer from chronic diseases have more exposure and contact with health services,4 and in them, somatic and mental diseases are ordinarily prioritised, and there is greater sensitivity to seeking care and associating physical problems with other physical ailments.

Having experienced a traumatic event was also associated with greater self-recognition of mental problems and disorders, since these events in some cases cause physical and mental ailments.37,38

Having some degree of emotional support was associated with greater self-recognition, which could be explained because the support of third parties allows the individual to have a way to channel the burden and psychological symptoms, and to subjectively minimise the burden and stress they are contending with.8,25,33

Greater family dysfunction is associated with greater self-recognition as the severity of family dysfunction increases, as has been found in studies carried out in Spain39 and Ecuador,40 in which higher recognition and prevalence of mental disorders were found in families with greater dysfunction. Possibly this is secondary to the lack, in families with dysfunction and internal conflicts, of the support and accompaniment that exist in other types of families; that is, due to their proximity, this would be the first group that the individual would approach to try to adapt and overcome difficulties or problems they find themselves facing.

One of the factors with the greatest association with self-recognition of mental problems and disorders in the raw analysis is the individual's perception of their own mental health. Thus, the worse the perception or sensation of poor mental health, the greater the association with the process of self-recognition. This is consistent with what has been reported in various studies carried out in Europe,8 the United States35,41 and Canada,33 and its explanation lies mainly in the fact that if the individual has a feeling of poor mental health, it is because they already present symptoms associated with psychopathology, such as symptoms of anxiety or depression, which alter their perception of their own mental health and allow self-recognition of these problems or disorders.

Meanwhile, alcohol abuse was associated with less self-recognition, which may be related to the denial attitude in which this type of people who consume illegal substances or alcohol often find themselves.

One of the greatest strengths of the study is having a representative sample of the Colombian population, which allows for the extrapolation of its findings to the country's adult population. In addition, having explored the association of various factors related to the self-recognition process allows us to elucidate or establish factors that can improve or decrease self-recognition of mental problems or disorders in the Colombian population. The use of validated instruments such as the CIDI and the SRQ-20 allows for adequate identification, and with it the confirmation that the self-recognition of psychopathology in individuals is valid and real.

Among the study's weaknesses is, first of all, the type of study design, given that, due to its characteristics, it is not possible to establish causal relationships, and therefore only possible associations with the factors or variables explored can be proposed. Another weakness of the study is the memory bias for questions related to having had mental health problems in the last year. This measurement, despite its difficulties, is still used in psychiatry and mental health, and is the best approximation to the prevalence of diseases. A social desirability bias may also be present, since in this type of survey the interviewees can give answers to misrepresent or diminish the negative image that some variables may have. For example, saying that you do feel the support of your family or neighbours because it is socially expected, even if you cannot really count on their support. However, an attempt was made to reduce this type of bias by training interviewers in neutrality, trust and listening skills in interviews.

To conclude, in addition to opening up an area of research in our country, this study provides data that add to knowledge in and from Latin America, and offers new options for the concept of self-recognition, which go a little beyond the usual practice, by selecting people with problems and disorders not yet detected, or who at least say they are not aware of them. This, at the same time, provides keys to visualising the importance of psychosocial factors not only regarding the influence of social wellbeing on mental wellbeing, but also of mental wellbeing as a motor of social wellbeing, wherein through the detection of the problems and disorders patients can begin a process of access to health.

ConclusionsThe process of self-recognition of mental problems and diseases is a fundamental part — it could almost be the first step — of the process to access mental health services, in any population and in the particular case of the adult population of Colombia. Therefore, it is necessary to establish factors or variables associated with it, in order to design or establish intervention measures or health policies regarding such variables, to control or promote them. This seeks to increase self-recognition of these diseases in Colombian adults and with it, possibly, access to care and attention.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection, for the loan of the National Mental Health Survey 2015 database.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-Restrepo C, Rodríguez MN, Eslava Schmalbach J, Ruiz R, Gil JF. Autorreconocimiento de trastornos y problemas mentales por la población adulta en la Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental en Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:92–100.