To date, few epidemiological studies compare the incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and isolated cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). The information is even more scarce in Latin America. The aim of this study is to describe the phenotype of CLE in a reference center in Colombia.

Materials and methodsA retrospective cross-sectional study was carried out. SLE was confirmed according to EULAR/ACR 2019 classification criteria and patients were simultaneously evaluated in the rheumatology and dermatology clinics. A descriptive and bivariate analysis was carried out. The institutional committee approved the study.

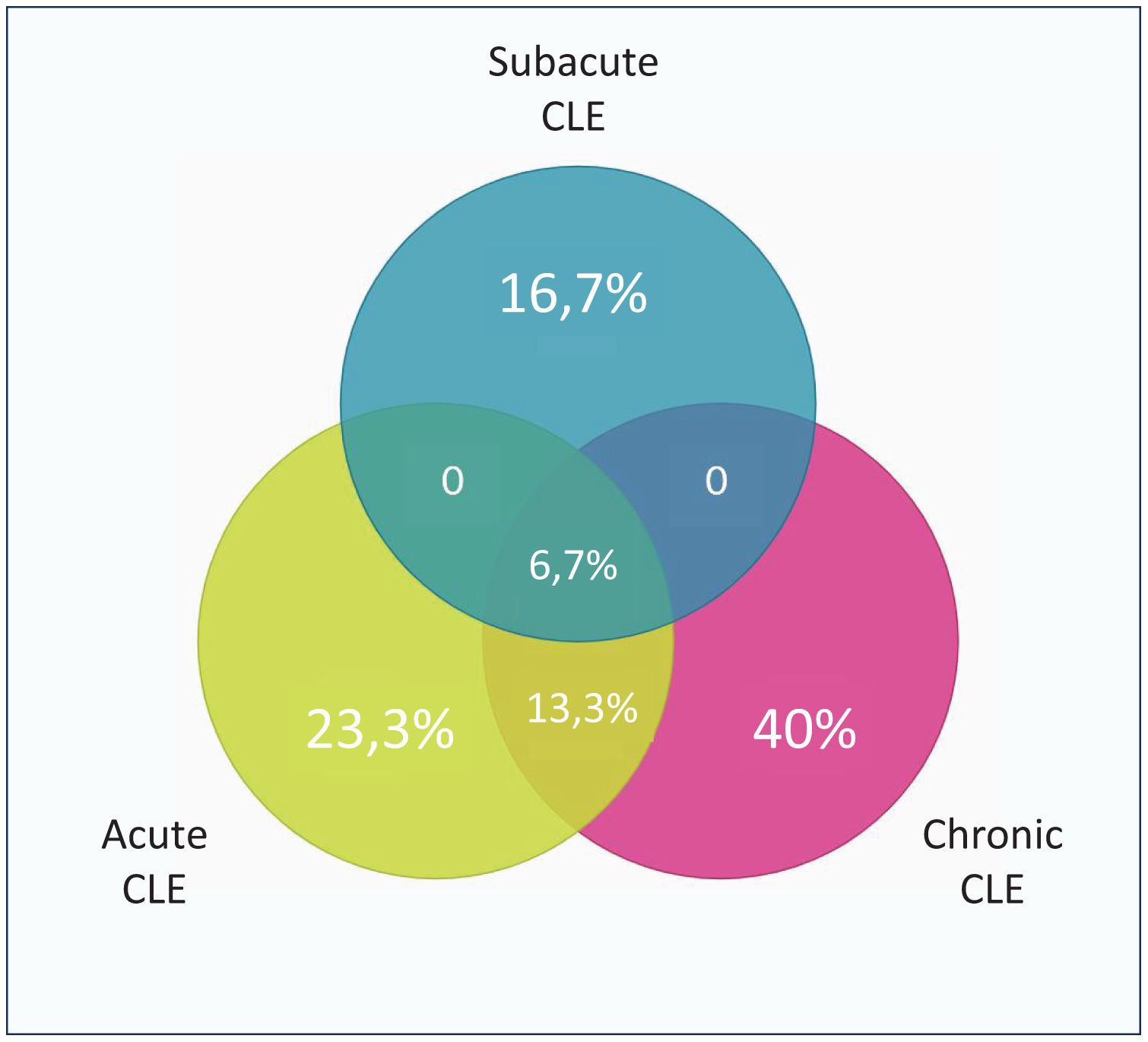

ResultsThirty participants were diagnosed with SLE and CLE. Most patients were female (83.3%), with a mean age of 37±13 years. Chronic CLE was the most prevalent subtype (46.7%), followed by acute (30%) and subacute (16.7%) CLE. There were statistically significant differences when comparing acute CLE and reduced C4 (p=.032); in subacute CLE and interstitial lung disease (p=.010); and in lymphopenia (p=.012) and thrombocytopenia (p=.046). Finally, there was a difference in patients with chronic CLE and the use of topical corticosteroid (p=.026), methotrexate (p=.036), and SLEDAI>3 points (p=.025).

ConclusionThis study provides valuable insights into the phenotypic characteristics and associations of CLE with systemic manifestations in the Colombian population, contributing to the understanding and managing of this complex autoimmune disease.

Hasta la fecha, pocos estudios epidemiológicos comparan la incidencia y la prevalencia del lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES) y el lupus eritematoso cutáneo (LEC) aislado, con información aún más escasa en Colombia.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de este estudio es describir el fenotipo del LEC en un centro de referencia en América Latina.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio transversal retrospectivo. Los pacientes tuvieron confirmación de LES según los criterios de clasificación EULAR/ACR 2019 y fueron evaluados simultáneamente en las clínicas de reumatología y dermatología. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo y bivariado. El comité institucional aprobó el estudio.

ResultadosA 30 participantes se les diagnosticó LES y LEC. La mayoría eran mujeres (83,3%), con una edad media de 37±13 años. El LEC crónico fue el subtipo más prevalente (46,7%), seguido del LEC agudo (30%) y subagudo (16,7%). Hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas al comparar LEC agudo y C4 reducido (p=0,032); LEC subagudo y enfermedad pulmonar intersticial (p=0,010), y en linfopenia (p=0,012) y trombocitopenia (p=0,046). Finalmente, hubo diferencia en pacientes con LEC crónico y el uso de corticoides tópicos (p=0,026), metotrexato (p=0,036) y SLEDAI >3puntos (p=0,025).

ConclusiónEste estudio proporciona información valiosa sobre las características fenotípicas y las asociaciones del LEC con manifestaciones sistémicas en la población colombiana, contribuyendo así a la comprensión y el manejo de esta compleja enfermedad autoinmune.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an heterogeneous autoimmune disease, that may present with cutaneous manifestations during any stage of the disease.1 In SLE, the skin is the second most affected organ (70–85%); and skin lesion may present as the first finding in 25% os SLE patients.2 On the other hand, cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) can exist as an entity without associated systemic autoimmunity or as a part of SLE.3

The annual incidence reported for SLE is approximately 1–10 per 100,000, with a prevalence of 5.8–130 per 100,000.4 Regarding the epidemiology of CLE, there is no global data, but an estimated incidence of 4.30 per 100,000 inhabitants, predominantly in women has been reported.4,5 It should be noted, that CLE in SLE is three times more frequent in men, being predominant in the Caucasian population, and it is the most frequent manifestation of photosensitivity.6

In Colombia, data from a descriptive study reported a prevalence for CLE of 76 cases per 100,000. They also reported a predominance in women (ratio 5:1) and discoid lupus was the predominant phenotype (45%).7 In Latin America, there is scarce information on CLE and its association with SLE. Therefore, this study aims to describe the phenotype of the cutaneous manifestations of SLE in a referral-center in Bogotá, Colombia.

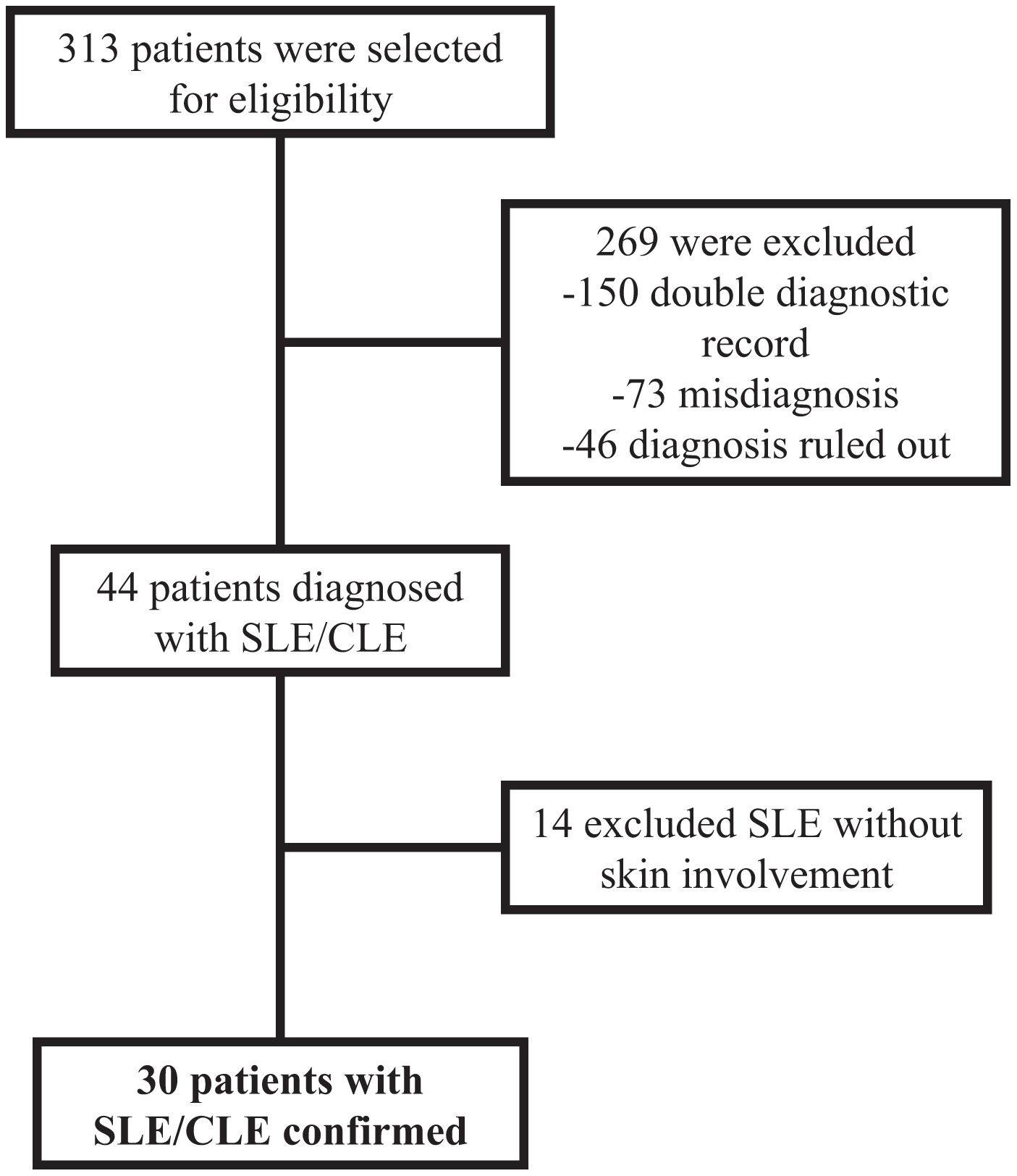

Materials and methodsA retrospective cross-sectional study was carried out during 2016–2019. Patients older than 18 years with a diagnosis of SLE were included. Patients were selected according to CIE/10 codes, including in the sample medical records coded with: M320, M321, M328, and M329. A subsequent review of the clinical history to confirm the diagnosis of the disease according to the EULAR/ACR 2019 classification criteria8 was carried out by personal trained with the classification criteria.

Sociodemographic, clinical, laboratory, and treatment characteristics were evaluated. Additionally, cutaneous characteristics were reviewed according to the dermatology/rheumatology registry.

A non-probabilistic convenience sampling was used, and a descriptive analysis was carried out. Quantitative variables were described by measures of central tendency and dispersion according to nature, and categorical variables were described through frequencies and percentages. A bivariate analysis was performed; quantitative variables were compared using the T student test, while the qualitative variables were compared using the Chi-square or Fisher's exact test. All analyses were performed using R Studio statistical software.

ResultsThirty patients were diagnosed with SLE and simultaneous CLE, and they were included (Fig. 1). Of this, 83.3% were female with a mean age of 37±13 years, and 46.7% had an additional comorbidity. Most of the patients have chronic CLE (46.7%), followed by acute CLE (30%), and subacute CLE (16.7%) (Fig. 2), there was an additional a group of patients with non-specific CLE lesions (6.6%). All patients with CLE have systemic compromise, mainly due to lupus nephritis (46.7%) or articular involvement (46.7%). Additionally, 60% have a severe SLE phenotype.

Patients with acute CLE had lesions in the malar region (66.7%), mainly presenting as erythema (77.8%). In comparison, patients with subacute CLE who had involvement of more than one area of the body in 60% of the cases, with plaque-type lesions as the predominant lesion (80%); On the other hand, the patients with chronic CLE mainly presented involvement of more than one area of the body (78.6%) and in the form of discoid lupus (78.6%). Histopathological correlation was reported in 60% of the patients, by skin biopsy. Of these, the diagnosis of CLE was compatible with the findings in 13 cases, there was nonspecific findings in 4 patients, and an alternate diagnosis was suggested in 1. On the other hand, 8 patients had a diagnosis by direct immunofluorescence in the skin which suggested CLE.

66.7% of the patients received any topical therapy; of these, 100% received topical corticosteroids, of which 50% were of high potency, and 50% of moderate potency. Additionally, 16.7% of patients received topical tacrolimus and 11.1% topical retinoids. On the other hand, 96.7% received systemic treatment, mainly with antimalarials (93.1%), followed systemic corticosteroids (72.4%) and azathioprine (65.52%). In 24.1% of the cases, they received management with biological therapy (n=4 rituximab, n=3 belimumab).

In the immune profile, all patients had ANA positivity, 50% had anti-dsDNA, 82.2% had anti-Ro, 44.4% had anti-La, and 58.6% had anti-Sm; also 3.3% had a positive beta 2 glycoprotein IgG/IgM and cardiolipins IgG/IgM were negative in all cases. The complete blood count revealed leukopenia in 58.6% of the patients, lymphopenia in 51.7%, anemia in 34.5%, thrombocytopenia in 3.4%, a reduction in complement C3 in 20.7%, and a C4 reduction in 37.9%. Disease activity (according to SLEDAI) was low in 33.3%, moderate in 14.3%, and severe in 52.4% of the patients.

The bivariate analysis showed statistically significant differences comparing acute CLE and a reduced C4 (p=0.032). As wells as in subacute CLE and interstitial lung disease (p=0.010), lymphopenia (p=0.012), and thrombocytopenia (p=0.046). Finally, for chronic CLE there was a difference in the use of topical corticosteroid (p=0.026), methotrexate (p=0.036), and a SLEDAI>3 points (p=0.025).

DiscussionCLE has a broad spectrum of manifestations, it diagnosis is essential since it could present as the first clinical manifestation of SLE and an early diagnosis is essential for proper management and a better prognosis.9 This study has results consistent with epidemiological data from Latin American,7,10,11 with most of the cutaneous manifestations being chronic CLE of the discoid subtype. For acute CLE manifested by malar erythema and subacute CLE in the form of plaques our data is in agreement with data described in an European multicenter cohort.12

Histopathology and immunopathology studies, may be helpful in the diagnosis of CLE specially when other studies are nonspecific.13 60% of our population had a skin biopsy with hematoxylin and eosin or direct immunofluorescence being able to provide data to confirm findings suggestive of CLE, then the possibility of this analysis should be encouraged in daily clinical practice.

In our population, there was predominance of female patients, which is in agreement with reports from United States4 and our country.7 We observed that acute CLE had more frequently a reduced C4. This is consistent, with data from a multicenter European cohort12 and a Colombian cross sectional study.14 Interestingly, no other specific autoantibody for SLE showed difference when classified by CLE subtypes as reported in other cohorts.12 This finding may be due to sample size. On the other hand, there were no differences regarding antibodies profile between subtypes, even when there is evidence of acute CLE, which usually presents with positive ANA, anti-dsDNA, and anti-Sm antibodies.1 Meanwhile, patients with CLE without SLE ANA and anti-dsDNA are relatively low (50% and 2%, respectively).6

There was an association of interstitial lung disease and subacute CLE, this association have been previously described in a case report in United States15 as a manifestation of a severe systemic disease. Regarding subacute CLE, lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia was higher in comparison with other forms of CLE, contrary to previously reported in other population,11,14 but these hematological manifestation are also related with disease activity.

In addition to topical corticosteroids antimalarials are fundamental treatment for CLE,9 our population reported a high adherence to this recommendation. Interestingly those patients with chronic CLE had higher usage of topical corticosteroid and methotrexate. It is evident that methotrexate an effective drug in CLE,9 and this supports our findings.

There was a higher frequency of patients with high disease activity (SLEDAI>3 points) in chronic CLE, and patient with chronic CLE presented most frequently with discoid lesions. This is not a part of the SLEDAI criteria, but it has been reported that patients treated for CLE, have a reduction in the SLEDAI score with a positive impact not only in mucocutaneous parameters but also in other domains.5,9 Making it important for patients with CLE to have a measurement of disease activity, damage of skin and other organs, as well as quality of life in every follow-up visit.9

This study tries to elucidate the association between the cutaneous manifestations and the systemic manifestations of SLE in our country where the evidence is limited. However, given the limited number of cases it is difficult to draw conclusions in this regard. For future studies, it is suggested to have a larger sample size, including a population that not only represents military personnel and their relatives but also provides new results that can be extrapolated to the general population.

The patients with SLE analyzed were classified as chronic CLE, followed by acute and subacute CLE. In patients with acute CLE the main compromise was in the malar region due to erythema, while patients with subacute CLE had predominantly plaque-type lesions; and finally, the patients with chronic CLE mainly presented involvement of more than one area of the body in the form of discoid lupus. There are variables associated with each CLE subtype an intense evaluation for extracutaneous manifestations should be encouraged in daily practice in dermatology and rheumatology.

Ethical considerationsThe present study was developed following medical and research ethics guidelines and was approved by the institutional committee (HMC-2020-0023). The authors declare that this article does not contain personal information that could identify patients.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study protocol design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank the Laboratory and Archive Departments of the Hospital Militar Central for their support during the data gathering process.