The case is presented of a 41 year-old male patient with chest pain, asthenia and adynamia. The imaging studies showed a mass in the anterior mediastinum, which according to the pathology report, was a thymoma. Also, the patient also had haemolytic anaemia and autoimmune hypothyroidism, and with no associated myasthenia gravis.

Describimos el caso de un paciente masculino de 41 años que cursa con cuadro clínico de dolor torácico, astenia y adinamia, con estudios imagenológicos que evidencian masa en mediastino anterior que corresponde a timoma, de acuerdo con el reporte de patología. Además cursa con anemia hemolítica e hipotiroidismo autoinmune, sin miastenia gravis asociada.

Thymoma is an infrequent neoplasm with an incidence of 1–5 cases per every million people/year, it occurs in all ages, with a peak incidence between 55 and 65 years.1

The initial diagnostic approach of thymoma is accomplished through computed axial tomography of the chest with contrast; however, the surgical resection with pathological study is the most important diagnostic tool and in addition is the treatment of choice, especially in stages III and IV. Adjuvant chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and cisplatin can be used in the case of unresectable tumour.1

Other pathological entities, so called parathymic syndrome, such as myasthenia gravis, bone marrow aplasia, hypogammaglobulinemia, among others, may coexist associated with the neoplastic picture.2

As evidenced in the case reports and review articles in the literature, the association between thymoma, haemolytic anaemia, autoimmune hypothyroidism and lupus-like syndrome is quite uncommon as parathymic syndrome, unlike the association between thymoma and myasthenia gravis, which is the most common and best studied association between this tumour and autoimmune disease.3–9

Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia is defined as the destruction of erythrocytes secondary to the presence of antibodies directed against erythrocyte membrane antigens. It has an incidence of 0.61–1.3 per 100,000 inhabitants per year. The first diagnostic approach is made with a complete blood count with evidence of decrease in the haemoglobin and haematocrit values, usually characterized as being an anaemia with normal corpuscular volumes, elevation of lactic dehydrogenase (associated with greater severity of the haemolysis), decrease in haptoglobin, high reticulocyte count, presence of positive direct Coombs test (which indicates autoimmune aetiology of the anaemia), presence of warm or cold antibodies (immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M, respectively). Finally, the study is based on the search for the aetiology, primary cause (idiopathic) or secondary (neoplasms, collagen diseases, or pharmacological).10,11

Autoimmune hypothyroidism or Hashimoto's thyroiditis is a chronic inflammation of the thyroid gland associated with an autoimmune component, being the most frequent autoimmune disease. Anti-peroxidase antibodies are the best serological marker for the diagnosis, being positive in 95% of patients, while the anti-thyroglobulin antibodies exhibit lower sensitivity (60–80%) and specificity than the above-mentioned.12

The lupus like or lupus imitators refer to a group of entities with clinical and paraclinical characteristics, including the profile of antibodies, similar to those described in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).13

Below we present the case report of a patient with thymoma, haemolytic anaemia, autoimmune hypothyroidism and lupus like as parathymic syndrome, with resolution of the haemolytic anaemia and negativity of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) after the surgical resection of the neoplasia at the mediastinal level.

Case presentationA 41-year-old male patient, who consulted due to a clinical picture of 8 days of evolution consisting of epigastric throbbing pain, associated with asthenia and adynamia, without fever or other symptoms. With a history of hypothyroidism of difficult management under hormone replacement therapy and a family history of SLE and rheumatoid arthritis. On physical examination the patient was tachycardic, with mucocutaneous pallor. The rest of the physical exam did not show relevant findings.

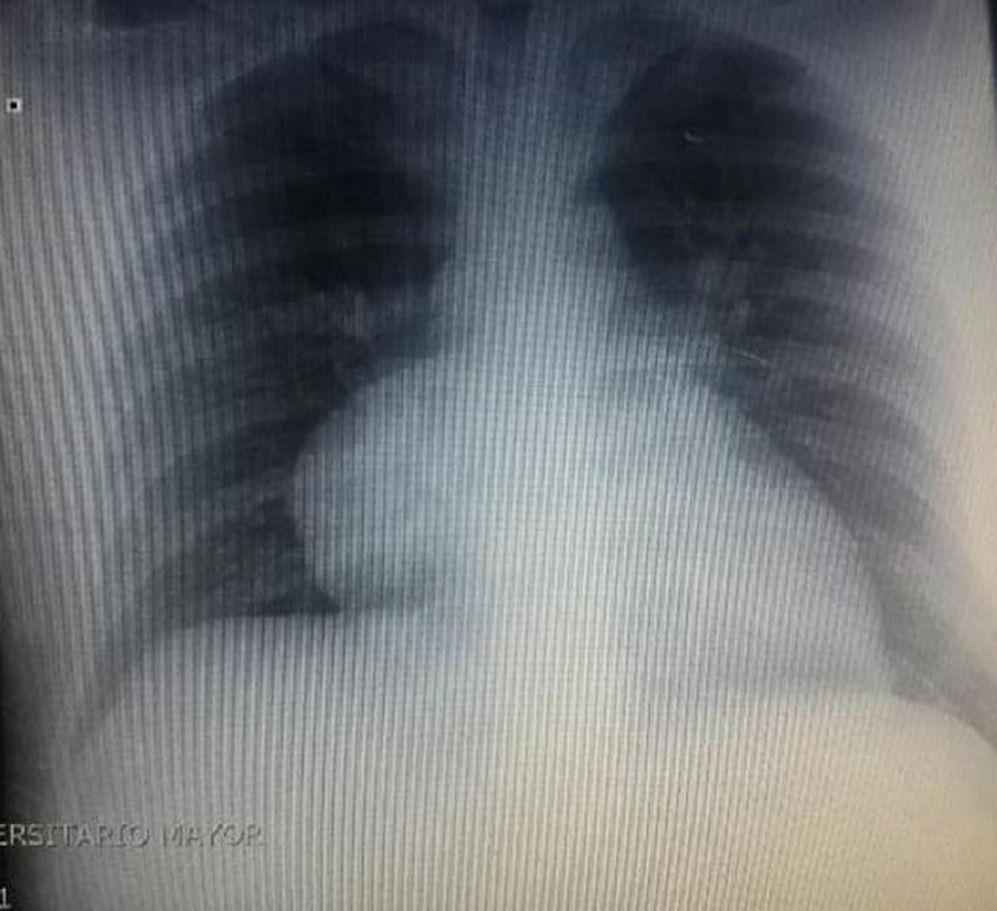

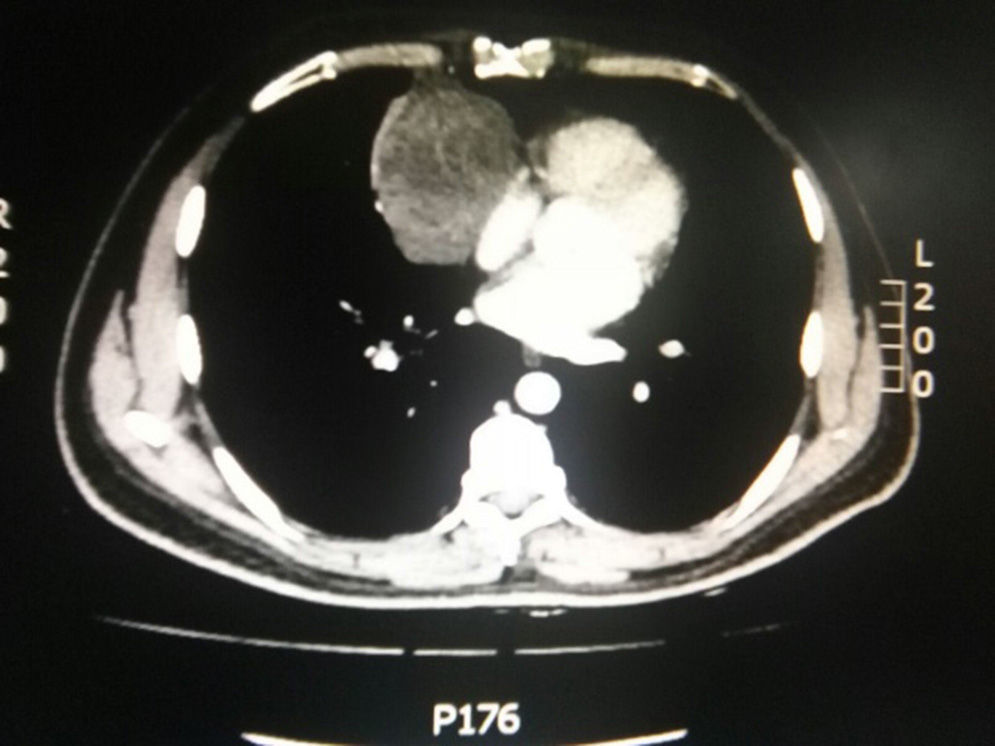

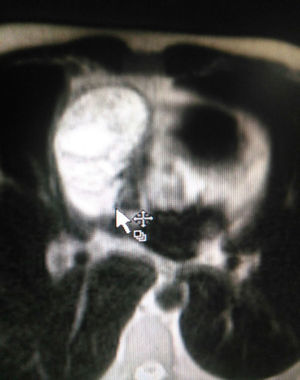

During hospitalization, the initial blood count shows bicytopenia (leukocytes 2660cells/mm3, haemoglobin 7.1g/dl, MCV 97.7fL), liver profile with hyperbilirubinemia at the expense of the indirect bilirubin (total bilirubin: 2.5mg/dl, indirect bilirubin 1.54mg/dl), positive Coombs test, with high corrected reticulocyte count (19.43%) and elevated lactate dehydrogenase 352IU/l; and therefore a picture of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia is considered, requiring doses of systemic steroid. In addition, the chest X-ray (Fig. 1) evidences mediastinal widening, and therefore a chest CT scan is requested (Fig. 2) finding a mass in the right cardiophrenic angle, solid, with smooth contours that suggests infiltration of the pericardium, and diameters greater than 70mm×65mm×64mm, compatible with thymoma, without being able to rule out lymphoma. Given the finding of bicytopenia and a mass which could correspond to lymphoma, a bone marrow aspiration is carried out, which reported hypercellularity with haematopoiesis of the three cell lines, erythroid hyperplasia with megaloblastic change and negative study for neoplastic infiltration.

Subsequently it is decided to perform a trucut biopsy of the mediastinal mass which documents ovoid cells intermingled with small lymphocytes, with immunohistochemical studies positive for CKAE1AE3, with a lymphoid population of T phenotype immunoreactive for CD5, without immunoreactivity for CD20, with ki67 showing cell proliferation in the lymphoid population, findings that correspond to a lesion with epithelial and T lymphoid component, that given the location is compatible with thymoma.

In addition, given that the patient has a hypothyroidism difficult to manage, with elevated TSH (16.6mIU/l) and a family history of autoimmune diseases, it was considered that this type of pathologies might also be present. ANA tests are requested, which are positive in 1/360 dilutions with homogeneous pattern, anti-thyroid antibodies higher than 400IU/ml (positive) and thyroid microsomal antibodies higher than 600IU/ml (positive) that allow us to make the diagnosis of hypothyroidism of autoimmune aetiology and lupus like.

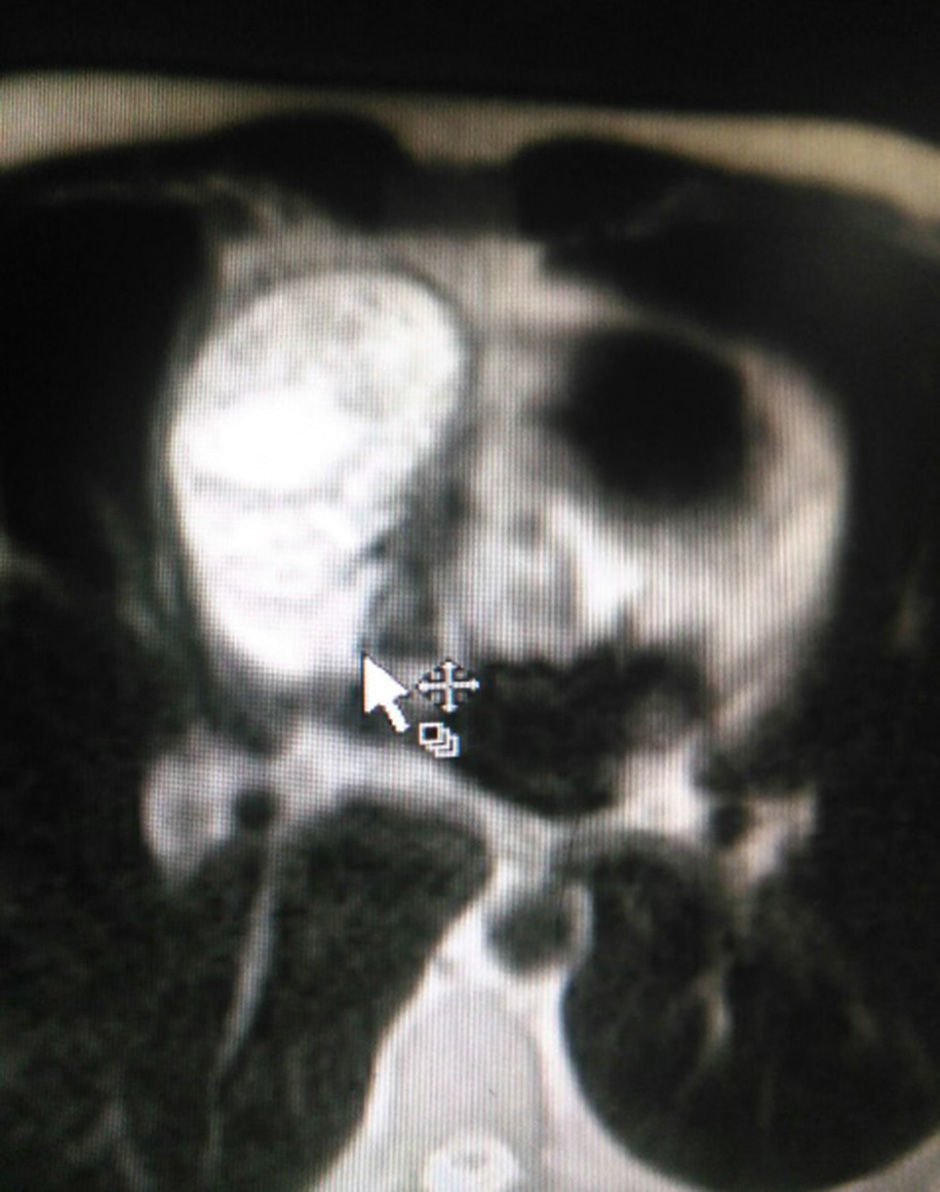

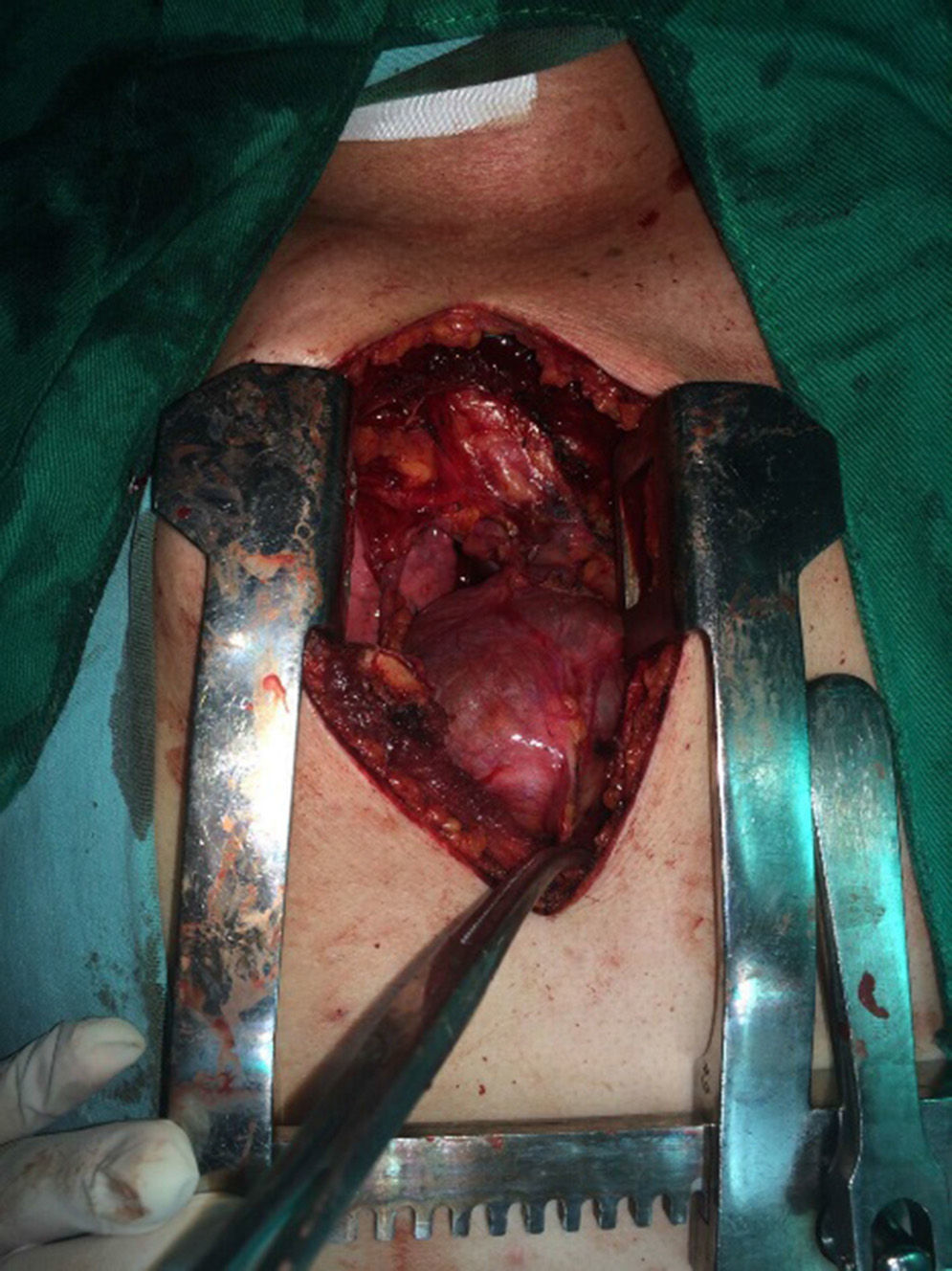

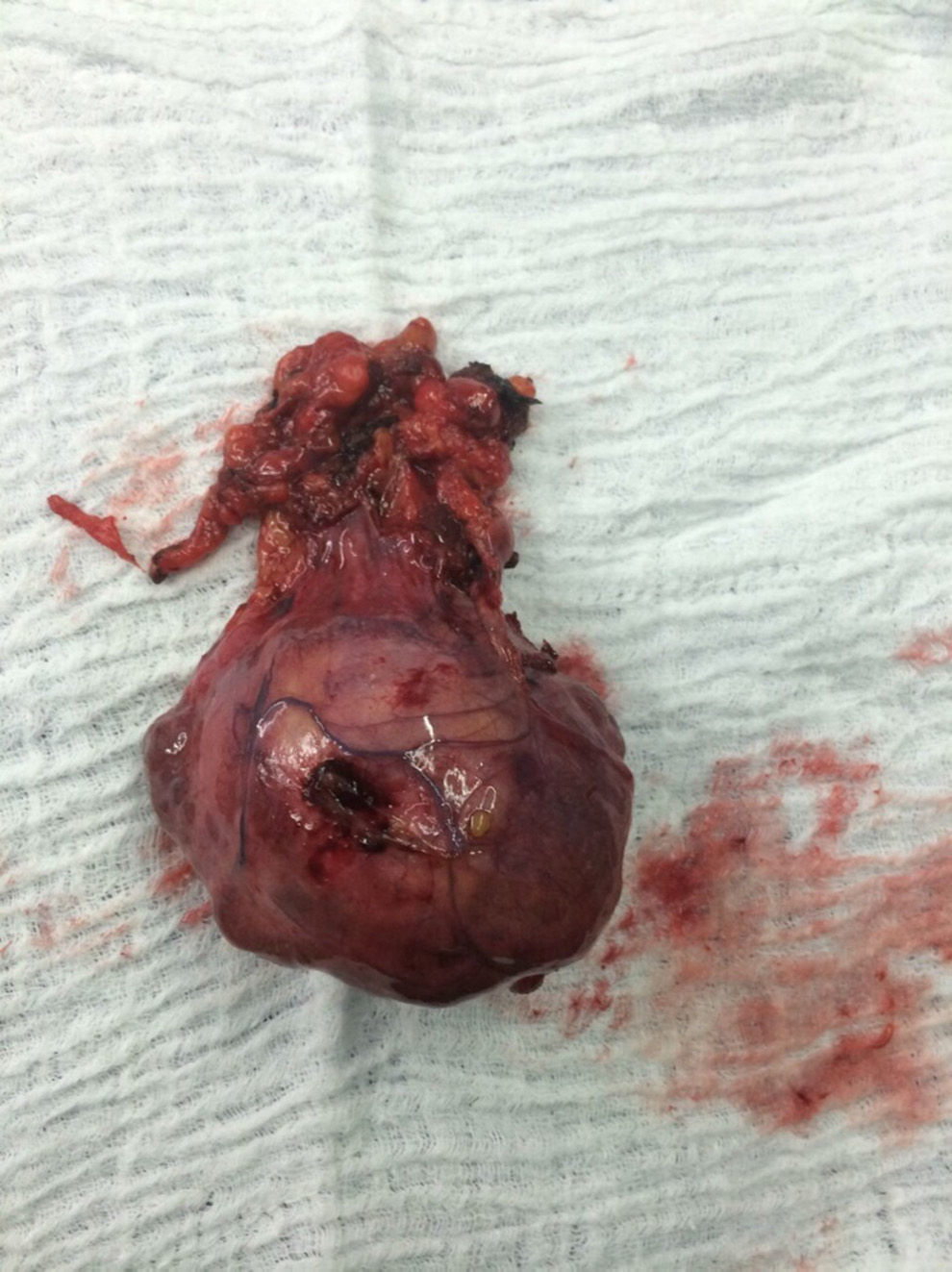

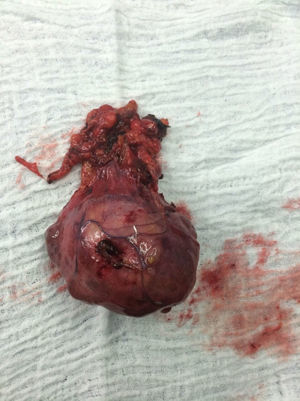

The patient is assessed by thoracic surgery who request tumour markers (carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha fetoprotein, beta subunit of chorionic gonadotropin, which were within normal ranges) and imaging studies including a testicular ultrasound with normal report and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thorax with contrast, in order to rule out pericardial commitment (Figs. 3 and 4), which documents anterior mediastinal mass in contact with the left atrium and the superior vena cava, which given the location of the lesion and the pericardial thickening and effusion, suggests invasion of the pericardial sac. With the report of the imaging study, thoracic surgery considers a resection of the mediastinal mass through sternotomy (Figs. 5 and 6), evidencing a mass in the anterior mediastinum of 12cm×8cm in intimate contact with the pericardium. This piece is sent to pathology which documents a type A thymoma with capsular commitment, with no evidence of involvement of the adjacent tissues or lymph node component, with immunohistochemistry positive for CKAE1AE3 epithelial component and positive for CD3, CD5 and CD99 lymphoid component.

The patient evolves satisfactorily in the postoperative period, the haematological cell lines were re-established after the thymus resection, and for this reason, discharged for outpatient monitoring. Further ANA were requested, which were negative.

DiscussionThymomas are infrequent neoplasms, representing less than 1% of all the types of cancers in the adult and 15% of mediastinal masses,9 with no sex predilection, being the male–female ratio 1:1.2,14 Of the total cases, 44% show malignancy and 56% are benign.2 The presence of parathymic syndrome, which makes reference to entities accompanying the tumoural picture, has been described in 40% of cases of thymoma.2

Autoimmune diseases related to thymoma have been associated with an alteration of the adaptive immunity, given the affectation of the thymus as a fundamental organ in the maturation of T cells, with production of clones of autoreactive T cells responsible for the autoimmune manifestations in these patients.3

Multiple theories have been proposed regarding the pathophysiology of thymoma and its association with autoimmunity, such as the theory of immature T cells, which makes reference to the lack of self-tolerance by the thymocytes of the thymoma, thus reacting against self epitopes; the genetic theory, in which the cells of the thymoma have genetic alterations in the expression of the major histocompatibility antigen, which would be associated with alterations in the recognition of antigens; the combined cellular and humoral theory, which makes reference in the first instance to an alteration in the CD4 T lymphocytes of the thymoma, leading to the activation of the B cells with the subsequent production of autoreactive antibodies15 and, finally, the theory that suggests that the necrosis of the neoplastic cells may result in inflammation and release of self-antigens, which can be recognized by the own immune system thus generating harmful responses.16

It has been described that thymoma occurs in 15% of patients with myasthenia gravis, being the most studied pathology together with this tumoural picture.4–9 In addition to this neurological picture, it has also been reported the appearance of thymoma in 10–15% of patients with bone marrow aplasia and in 10% of patients with hypogammaglobulinemia,5,15,17 and conversely, when the thymoma is the primary disease, is associated with myasthenia gravis in 35% of cases, with bone marrow aplasia in 50% and with hypogammaglobulinemia in 10%.2

Other entities associated much less frequently with thymoma are SLE, sarcoidosis, scleroderma, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren's syndrome,15 dermatopolymyositis, pemphigus vulgaris,18 chronic candidiasis,19 ulcerative colitis, multiple sclerosis,9 nocturnal paroxysmal haemoglobinuria20 and hyperparathyroidism.21

With regard to the haematological commitment associated with thymoma, bone marrow aplasia and haemolytic anaemia are the most frequent entities.5 The first case of haemolytic anaemia as the first manifestation of malignant thymoma was described in 1985, in a patient with clinical and paraclinical characteristics similar to the case described in this report, given by symptoms suggestive of anaemia associated with incidental finding of thymoma in the chest X-ray and haemolysis profile by positive Coombs test, elevated LDH and hyperbilirubinemia at the expense of the indirect bilirubin with total resolution of the anaemic picture with a course of corticosteroids and surgical resection of the mediastinal mass.22

The literature provides about 19 cases of thymoma associated with haemolytic anaemia, being most frequent the association with type C thymoma and secondly with type A thymoma,2,3,5,22 likewise it has been documented the difference in the order of appearance of both entities. In 16% of cases it courses initially with the manifestation of haemolysis and subsequently with the presence of a thymic mass.22 In 44.5%, the thymoma precedes the haemolytic anaemia and in 39% of cases the haemolytic anaemia and the thymoma are diagnosed simultaneously,2 as in the case reported in this article.

The treatment for the haemolytic anaemia associated with thymoma is based on the use of corticoids in conventional doses of 1–1.5mg/kg for 3 weeks, with clinical improvement in 70–90% of patients, in which case is recommended the gradual reduction of the dose of corticoid if there is evidence of sustained clinical improvement.2 Patients refractory to the use of corticosteroids may benefit from other pharmacological alternatives such as azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate mofetil and biological therapy with rituximab and alemtuzumab and splenectomy.10,11

In more than 50% of the cases reviewed (10 cases)2,5,22 was documented the remission of the haemolytic anaemia with the surgical resection of the thymoma associated with a previous therapy with corticosteroids,3 as happened in the outcome of the patient reported in this article.

Among the extension studies of our patient, unlike most of the cases reported in the literature, it was evidenced positivity for antithyroid antibodies, thyroid microsomal antibodies and ANA suggestive of hypothyroidism of autoimmune aetiology and lupus like, respectively.

There is evidence in the literature of the association between thymoma and thyroid disease,5,15 having been found, mainly, the coexistence of myasthenia gravis in 5–11.9%; and the presence of hypothyroidism with Hashimoto's thyroiditis, as in the case of our patient, represents less than half of the cases reported with Graves’ disease (2–4% versus 5–8%). In these cases it has been observed that thymectomy has no effect on the recovery of the thyroid function.5

Regarding SLE and thymoma, it has been described the simultaneous appearance of these two pathologies5,9,15,23,24 in between 1.5 and 2% of cases, while the development of SLE in patients with thymoma has an occurrence of 2–10%.

Our patient did not meet the classification criteria for SLE, however, because of the report of positive ANA and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, is associated to an entity known in the medical terminology as lupus like or imitators of lupus, characterized by presenting 2 or 3 criteria for this pathology, without complying fully with the characteristic clinical picture.13 This entity can be associated to the aberrant immune system upon the affection of the immunity acquired in the thymic alteration. Regarding the effect of thymectomy on lupus activity, it has been reported in the literature that after the surgical procedure 5 patients did not presented any effect, 6 patients increased the lupus activity and 7 patients showed clinical and paraclinical improvement of the lupus picture.5

In conclusion, although thymoma is a rare pathology, it may be associated with different entities, usually of autoimmune nature. Taking into account the review of the literature, we present the clinical case of a patient with thymoma and haemolytic anaemia associated with other autoimmune manifestations such as hypothyroidism and lupus like, which is very infrequent as parathymic syndrome in patients with thymoma. Currently, the initial recommendation concerning the treatment of these entities is to start short courses of corticosteroids associated with the surgical resection of the mediastinal mass, obtaining satisfactory results in the vast majority of cases, as in the case of the patient reported in this article.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Hurtado Amézquita C, Páez Ardila HA, Pabón Duarte L, Tiusabá Rojas PC. Anemia hemolítica secundaria a timoma sin miastenia gravis como síndrome paratímico: presentación de un caso. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2016;23:204–209.