To study quality of sleep in patients with psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and to investigate the association of sleep disturbances with other variables.

Methodology and methodsPatients ≥18 years old with a diagnosis of PsA (CASPAR criteria). Sociodemographic and clinical data, physical exam. For each case, an age-sex matched control was included. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression were administered to both patients with PsA and controls.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics. Univariate and multivariate analysis. Spearman correlation. Linear and multiple logistic regression.

Results36 patients with PsA and 37 controls, 52.8% male, median age 57 years. Median PsA disease duration of 11 years. The ICSP was higher in patients with PsA than in controls (7.8±4.1 vs. 4.6±2.9, respectively, p<.001). A total of 27 patients (64.3%) presented sleep disturbances (ICSP≥5) vs. 15 controls (35.7%), p=.004. The presence of sleep disturbance in patients with PsA was associated with higher pain (6.5±2.4mm vs. 3.4±3.1mm, p=.01) and greater depression (PHQ-9 18 vs. 9, p=.05). The ICSP questionnaire correlated positively with PHQ-9, pain, night pain, MASES, PsAQoL, and DAPSA. In the linear regression analysis, both pain (β: .44, p=.01) and depression (β: .38, p=.03) were independently associated with sleep disorders. And in multiple logistic regression, the only variable independently associated with ICSP≥5 was pain (OR: 1.64, p=.023).

ConclusionsMore than 60% of patients with PsA have sleep disturbance and the variables independently associated with it are pain and depression.

Estudiar la calidad del sueño en pacientes con artritis psoriásica (APs) e investigar la asociación de los disturbios del sueño con otras variables.

Metodología y métodosSe empleó una muestra de pacientes con diagnóstico de APs (criterios CASPAR), de edad mayor o igual a 18 años. Se tuvieron en cuenta los datos sociodemográficos y clínicos, y el examen físico. Por cada caso se incluyó un control pareado por sexo y edad. Se utilizaron el Índice de Calidad de Sueño de Pittsburgh (ICSP) y el Patient Health Questionnaire-9 para depresión (PHQ-9).

Análisis estadísticoSe llevó a cabo estadística descriptiva, análisis uni y multivariado, correlación de Spearman y regresión lineal y logística múltiple.

ResultadosTreinta y seis pacientes con APs y 37 controles, de los cuales el 52,8% fueron varones, con una edad mediana de 57 años. El tiempo mediano de evolución de APs fue de 11 años. El ICSP fue mayor en pacientes con APs que en controles (7,8±4,1 vs. 4,6±2,9, p<0,001). Veintisiete pacientes (64,3%) presentaron disturbios del sueño (ICSP≥5) vs. 15 controles (35,7%), p=0,004. La presencia de disturbios del sueño en pacientes con APs se asoció con mayor dolor (6,5±2,4mm vs. 3,4±3,1mm, p=0,01) y mayor depresión (PHQ-9 18 vs. 9, p=0,05). El cuestionario ICSP correlacionó positivamente con PHQ-9, dolor, dolor nocturno, MASES, PsAQoL y DAPSA. En el análisis de regresión lineal, tanto el dolor (β: 0,44, p=0,01) como la depresión (β: 0,38, p=0,03) se asociaron independientemente con los trastornos del sueño, en tanto que en la regresión logística múltiple la única variable asociada independientemente con ICS p≥5 fue el dolor (OR: 1,64, p=0,023).

ConclusionesMás del 60% de los pacientes con APs tienen disturbio del sueño y las variables asociadas con independencia de este son el dolor y la depresión.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease characterized by skin and musculoskeletal involvement.1,2 Most patients suffering from PsA have at least one comorbidity, and among them the most frequent are metabolic syndrome, obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and mental health disorders.3,4

In a systematic literature review that included 24 studies in 31,227 patients with PsA, the pooled prevalence of anxiety was 33% (95% CI 17–53%) depression was observed in 20% (95% CI 8–35%) and sleep problems were common (84%).5 Recently, our group published a study of 100 patients with PsA from the IREP Argentina Psoriatic Arthritis Registry (RAPSODIA), of whom 26% and 59% presented major depression and anxiety, respectively. Both depression and anxiety were associated with more pain and higher disease activity.6 In another study of the same cohort, 30% of 112 patients with PsA presented a visual graduate fatigue scale ≥6cm and this was independently associated with higher peripheral joint involvement and worse quality of life.7 Patients with PsA suffer from depression and mood/behavior changes, fatigue, sleep disorders, altered body image, and this psychological burden, negatively affects the quality of life of our patients.8–10

In general, sleep disorders are an independent risk factor for functional disability, low work performance and high costs.11

Some studies have reported that the prevalence of sleep disturbances in both patients with psoriasis and PsA is more frequent than in the general population. This seems to be fundamentally related to the pruritus associated with psoriasis and the pain secondary to skin and joint involvement.9,12–19

To our knowledge, there are no data in Argentina on the quality of sleep in patients with PsA. For this reason, the objectives of this study were to determine the quality of sleep in patients with PsA and to investigate the association between sleep disturbances and sociodemographic and clinical variables.

MethodsA case–control study was conducted in August 2016. Patients ≥18 years of age diagnosed with PsA according to CASPAR criteria of the IREP Argentina Psoriatic Arthritis Registry (RAPSODIA)20 were included. Those patients with difficulties in completing the self-questionnaires (illiterate, blind) and patients who, according to the investigator's criteria, had uncompensated comorbidities that could have a significant impact on sleep quality and were not directly related to PsA were excluded. A control person from the general population matched for sex and age (±3 years) was included. Both patients and controls signed informed consent for participation in the study.

Sociodemographic data (sex, age, marital status, cohabitants, years of formal education, occupation, physical activity in hours per week and type, social insurance), data related to PsA (disease duration, type of predominant musculoskeletal involvement, form of onset and evolution, and extramusculoskeletal manifestations), toxic habits (alcohol, tobacco, pack-years), presence of comorbidities, and treatment received. Weight (cm) and height (kg) were measured and body mass index (BMI) [weight/height2]21 and cervical circumference in cm were calculated.

Peripheral disease activity was assessed by counting 66/68 swollen and tender joints, respectively, morning stiffness (in min), pain, fatigue, patient global assessment (PGA) and physician global assessment (PhGA) by visual numerical scale (VNS), dactylitis and enthesitis by Maastricht ankylosing spondylitis enthesitis score (MASES).22 Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) values in mm/h and C-reactive protein (CRP) in mg/dl obtained on the same day of the visit or at most two weeks before were recorded. Composite disease activity score 28 (DAS28),23 disease activity in psoriatic arthritis (DAPSA)24 and composite psoriatic disease activity index (CPDAI)25 were calculated. Also, the presence of minimal disease activity (MDA)26 was confirmed.

Skin involvement was determined by psoriasis area and severity index (PASI).27 The extension of psoriasis was assessed using the body surface area (BSA)28 and the presence of nail psoriasis was consigned.

Self-questionnaires were administered to estimate: functional capacity health assessment questionnaire (HAQ-A),29 psoriatic arthritis quality of life (PsAQoL)30,31 and dermatology life quality index (DLQI),32 disease activity by routine assessment of patient index data 3 (RAPID3)33 and axial involvement by bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index (BASDAI),34 bath ankylosing spondylitis functional index (BASFI).35,36

Both patients and controls completed questionnaires to assess sleep quality, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)37 and depression Patient Health Questionnaire Depression Severity Score (PHQ-9).38 The PSQI questionnaire has 19 questions grouped into seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disorders, sleep medication use, and daytime sleep dysfunction. Each component is rated on a scale of 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty). The sum of the components results to a final value, a higher score indicates a lower quality of sleep. Its range is from 0 to 21. A score ≥5 distinguishes subjects with poor sleep from those who sleep well, with high sensitivity and specificity (89.6 and 86.5%, respectively).37 The PHQ-9 consists in 9 questions, which assess the frequency of depressive symptoms (corresponding to DSM-IV criteria)39 in the last two weeks. Each question is answered using a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3 (0=“never”, 1=“some days”, 2=“more than half the days”, 3=“almost every day”), and the final calculation is the sum of the 9 answers, the range of the score goes from 0 to 27. According to the result, the patients were classified as follows: 0–4 without depression, 5–9 mild depression, 10–14 moderate depression, 15–19 severe depression and 20–27 very severe depression. A value greater than or equal to 10 identified the presence of major depression.38

Ethical considerationsThis study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP), defined in the International Conference on Harmonization and in accordance with the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki, Law 3301/09 and the guidelines of the Ethics Committee. Personal identification data will remain anonymous and protected according to current international and national regulations to guarantee confidentiality, in accordance with the Personal Data Protection Law No. 25,326/2000. The protocol and the informed consent of the patients were approved by an Independent Ethics Committee, prior to the beginning of the study.

For statistical analysis, descriptive statistics were performed. Continuous variables were expressed according to their distribution, in medians and interquartile range (IQR) or mean (χ¯) and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables in frequency and percentage. To compare continuous variables, Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney test were used, according to their distribution, and Chi2 test or Fisher's exact test were used to compare categorical variables. Spearman correlation analysis. In order to identify sociodemographic and clinical variables independently associated with the presence of sleep quality disturbances, multivariate linear and logistic regression models were used, using the value of the PSQI result and the presence of sleep disturbances as dependent variables (ICSP≥5), respectively. In these multiple regression models, those independent variables that showed an association in the univariate analysis of less than 0.1, or those that the researcher considered relevant, either by interaction or by adjustment, were included. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant and all analysis were performed using the R version 4.0.0 program (Free Software Foundation, Inc., Boston, USA).

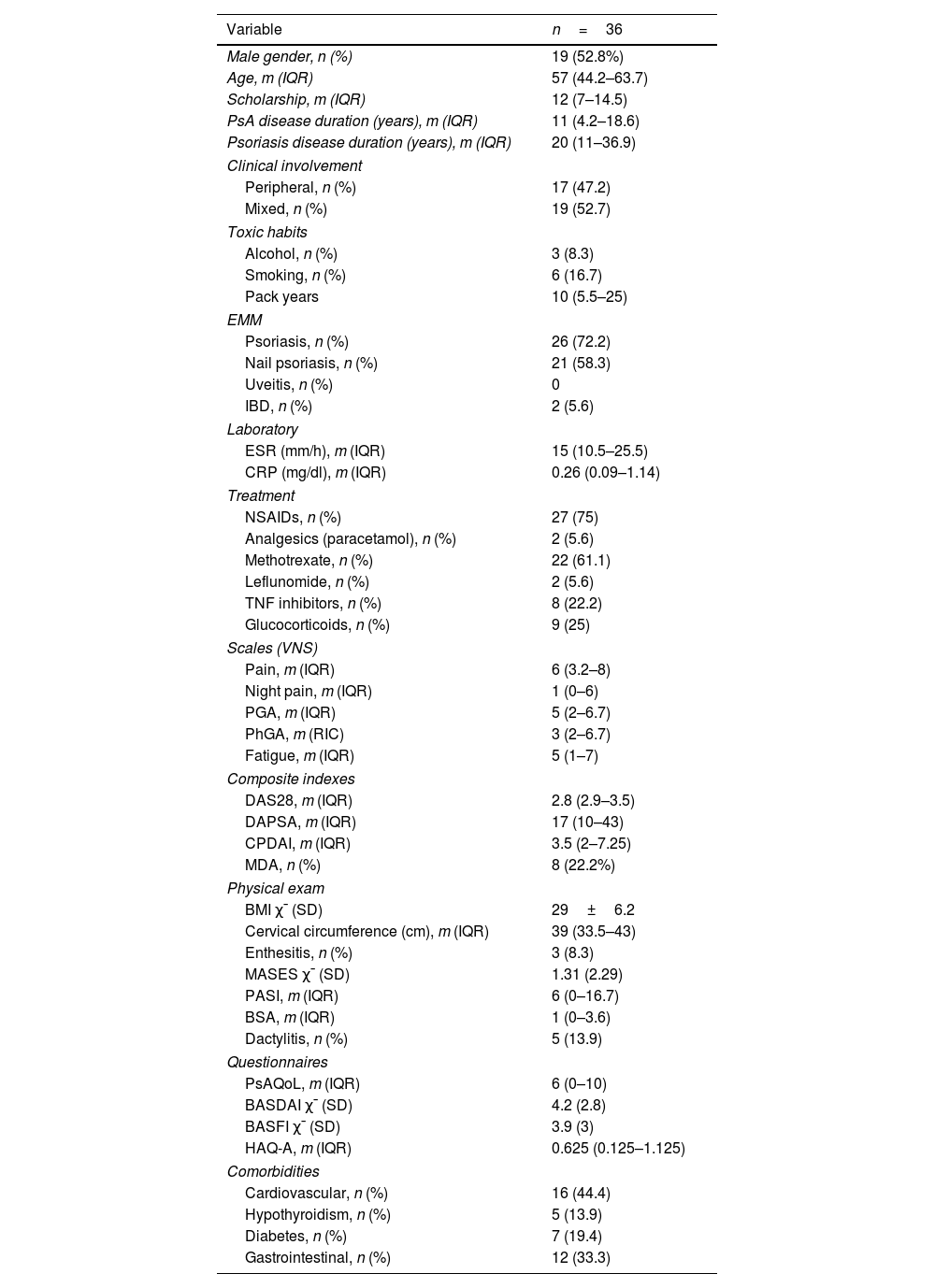

ResultsThirty six consecutive patients with PsA from the RAPSODIA cohort and 37 age- and sex-matched controls were studied. The patients with PsA had a median age of 57 years (IQR: 44.2–63.7) and 19 (52.8%) were male. Controls had a median age of 50 years (IQR: 44.5–61.5) and 22 (59.5%) were male. There were no significant differences in age and sex between patients and controls. Seventeen patients had pure peripheral involvement and 19 mixed involvement. The median PsA disease duration was 11 years (IQR: 4.2–18.6), and psoriasis duration was 20 years (IQR: 11–36.9). The patients had a mean BMI of 29±6.2 and 8 (22.2%) were in MDA. The rest of the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics are described in Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics in 36 patients with PsA.

| Variable | n=36 |

|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 19 (52.8%) |

| Age, m (IQR) | 57 (44.2–63.7) |

| Scholarship, m (IQR) | 12 (7–14.5) |

| PsA disease duration (years), m (IQR) | 11 (4.2–18.6) |

| Psoriasis disease duration (years), m (IQR) | 20 (11–36.9) |

| Clinical involvement | |

| Peripheral, n (%) | 17 (47.2) |

| Mixed, n (%) | 19 (52.7) |

| Toxic habits | |

| Alcohol, n (%) | 3 (8.3) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 6 (16.7) |

| Pack years | 10 (5.5–25) |

| EMM | |

| Psoriasis, n (%) | 26 (72.2) |

| Nail psoriasis, n (%) | 21 (58.3) |

| Uveitis, n (%) | 0 |

| IBD, n (%) | 2 (5.6) |

| Laboratory | |

| ESR (mm/h), m (IQR) | 15 (10.5–25.5) |

| CRP (mg/dl), m (IQR) | 0.26 (0.09–1.14) |

| Treatment | |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 27 (75) |

| Analgesics (paracetamol), n (%) | 2 (5.6) |

| Methotrexate, n (%) | 22 (61.1) |

| Leflunomide, n (%) | 2 (5.6) |

| TNF inhibitors, n (%) | 8 (22.2) |

| Glucocorticoids, n (%) | 9 (25) |

| Scales (VNS) | |

| Pain, m (IQR) | 6 (3.2–8) |

| Night pain, m (IQR) | 1 (0–6) |

| PGA, m (IQR) | 5 (2–6.7) |

| PhGA, m (RIC) | 3 (2–6.7) |

| Fatigue, m (IQR) | 5 (1–7) |

| Composite indexes | |

| DAS28, m (IQR) | 2.8 (2.9–3.5) |

| DAPSA, m (IQR) | 17 (10–43) |

| CPDAI, m (IQR) | 3.5 (2–7.25) |

| MDA, n (%) | 8 (22.2%) |

| Physical exam | |

| BMI χ¯ (SD) | 29±6.2 |

| Cervical circumference (cm), m (IQR) | 39 (33.5–43) |

| Enthesitis, n (%) | 3 (8.3) |

| MASES χ¯ (SD) | 1.31 (2.29) |

| PASI, m (IQR) | 6 (0–16.7) |

| BSA, m (IQR) | 1 (0–3.6) |

| Dactylitis, n (%) | 5 (13.9) |

| Questionnaires | |

| PsAQoL, m (IQR) | 6 (0–10) |

| BASDAI χ¯ (SD) | 4.2 (2.8) |

| BASFI χ¯ (SD) | 3.9 (3) |

| HAQ-A, m (IQR) | 0.625 (0.125–1.125) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Cardiovascular, n (%) | 16 (44.4) |

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 5 (13.9) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 7 (19.4) |

| Gastrointestinal, n (%) | 12 (33.3) |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; n: number; m: median; IQR: interquartile range; EMM: extra musculoskeletal manifestations; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C reactive protein; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; VNS: visual numerical scale; PGA: patient global assessment; PhGA: physician global assessment; DAS28: disease activity score; DAPSA: disease activity in psoriatic arthritis; CPDAI: composite psoriatic disease activity index; MDA: minimal disease activity; BMI: body mass index; SD: standard deviation; MASES: Maastricht ankylosing spondylitis enthesitis score; PASI: psoriasis area and severity index; BSA: body surface area; PsAQoL: psoriatic arthritis quality of life; BASDAI: bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index; HAQ-A: health assessment questionnaire-Argentinean version.

Schneeberger EE, personal elaboration.

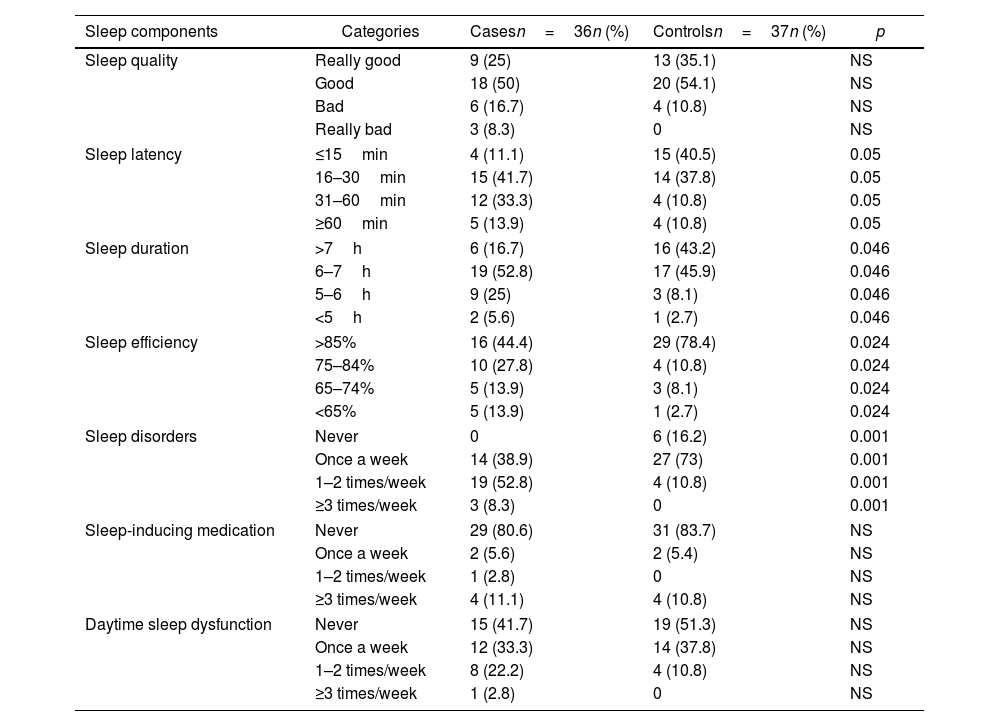

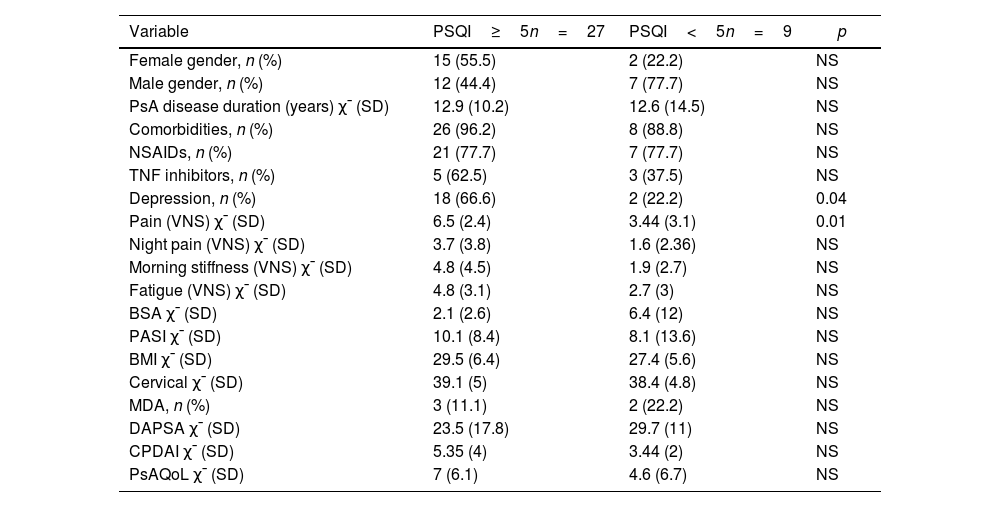

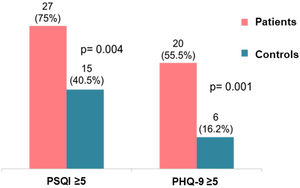

The result of the PSQI was higher in patients with PsA than in the controls (7.8±4.1 vs. 4.6±2.9, respectively, p=0.001), as well as the PHQ-9 (7.7±6.9 vs. 1.9±2.1, respectively, p=0.001). Similarly, 27 patients (75%) had sleep disturbances (ICSP≥5) versus 15 controls (40.5%), p=0.004, and 20 patients (55.5%) had depression (PHQ-9≥5) versus 6 controls (16.2%), p=0.001 (Fig. 1). When analyzing the components of sleep evaluated, it was observed that patients with PsA presented significantly higher sleep latency, shorter sleep duration, worse sleep efficiency, and a higher frequency of sleep disorders (Table 2). The presence of sleep disturbances (ICSP≥5) in patients with PsA was associated with higher pain VNS compared to patients without sleep disturbances (6.5±2.4cm vs. 3.4±3.1cm, p=0.01) and higher depression (PHQ-9: 18 vs. 9, p=0.05) (Table 3). Patients who were not in MDA showed a higher PHQ-9 score (8.96±7.02 vs. 3.13±4.26, p=0.03).

Comparison of sleep components between cases and controls.

| Sleep components | Categories | Casesn=36n (%) | Controlsn=37n (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep quality | Really good | 9 (25) | 13 (35.1) | NS |

| Good | 18 (50) | 20 (54.1) | NS | |

| Bad | 6 (16.7) | 4 (10.8) | NS | |

| Really bad | 3 (8.3) | 0 | NS | |

| Sleep latency | ≤15min | 4 (11.1) | 15 (40.5) | 0.05 |

| 16–30min | 15 (41.7) | 14 (37.8) | 0.05 | |

| 31–60min | 12 (33.3) | 4 (10.8) | 0.05 | |

| ≥60min | 5 (13.9) | 4 (10.8) | 0.05 | |

| Sleep duration | >7h | 6 (16.7) | 16 (43.2) | 0.046 |

| 6–7h | 19 (52.8) | 17 (45.9) | 0.046 | |

| 5–6h | 9 (25) | 3 (8.1) | 0.046 | |

| <5h | 2 (5.6) | 1 (2.7) | 0.046 | |

| Sleep efficiency | >85% | 16 (44.4) | 29 (78.4) | 0.024 |

| 75–84% | 10 (27.8) | 4 (10.8) | 0.024 | |

| 65–74% | 5 (13.9) | 3 (8.1) | 0.024 | |

| <65% | 5 (13.9) | 1 (2.7) | 0.024 | |

| Sleep disorders | Never | 0 | 6 (16.2) | 0.001 |

| Once a week | 14 (38.9) | 27 (73) | 0.001 | |

| 1–2 times/week | 19 (52.8) | 4 (10.8) | 0.001 | |

| ≥3 times/week | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 0.001 | |

| Sleep-inducing medication | Never | 29 (80.6) | 31 (83.7) | NS |

| Once a week | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.4) | NS | |

| 1–2 times/week | 1 (2.8) | 0 | NS | |

| ≥3 times/week | 4 (11.1) | 4 (10.8) | NS | |

| Daytime sleep dysfunction | Never | 15 (41.7) | 19 (51.3) | NS |

| Once a week | 12 (33.3) | 14 (37.8) | NS | |

| 1–2 times/week | 8 (22.2) | 4 (10.8) | NS | |

| ≥3 times/week | 1 (2.8) | 0 | NS | |

n: number; NS: not significant.

Schneeberger EE, personal elaboration.

Comparison of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between patients with PsA with and without sleep disturbances.

| Variable | PSQI≥5n=27 | PSQI<5n=9 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender, n (%) | 15 (55.5) | 2 (22.2) | NS |

| Male gender, n (%) | 12 (44.4) | 7 (77.7) | NS |

| PsA disease duration (years) χ¯ (SD) | 12.9 (10.2) | 12.6 (14.5) | NS |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 26 (96.2) | 8 (88.8) | NS |

| NSAIDs, n (%) | 21 (77.7) | 7 (77.7) | NS |

| TNF inhibitors, n (%) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) | NS |

| Depression, n (%) | 18 (66.6) | 2 (22.2) | 0.04 |

| Pain (VNS) χ¯ (SD) | 6.5 (2.4) | 3.44 (3.1) | 0.01 |

| Night pain (VNS) χ¯ (SD) | 3.7 (3.8) | 1.6 (2.36) | NS |

| Morning stiffness (VNS) χ¯ (SD) | 4.8 (4.5) | 1.9 (2.7) | NS |

| Fatigue (VNS) χ¯ (SD) | 4.8 (3.1) | 2.7 (3) | NS |

| BSA χ¯ (SD) | 2.1 (2.6) | 6.4 (12) | NS |

| PASI χ¯ (SD) | 10.1 (8.4) | 8.1 (13.6) | NS |

| BMI χ¯ (SD) | 29.5 (6.4) | 27.4 (5.6) | NS |

| Cervical χ¯ (SD) | 39.1 (5) | 38.4 (4.8) | NS |

| MDA, n (%) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (22.2) | NS |

| DAPSA χ¯ (SD) | 23.5 (17.8) | 29.7 (11) | NS |

| CPDAI χ¯ (SD) | 5.35 (4) | 3.44 (2) | NS |

| PsAQoL χ¯ (SD) | 7 (6.1) | 4.6 (6.7) | NS |

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; n: number; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; χ¯: mean; SD: standard deviation; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TNF: tumor necrosis factor; VNS: visual numerical scale; BSA: body surface area; PASI: psoriasis area and severity index; BMI: body mass index; MDA: minimal disease activity; DAS28: disease activity score; DAPSA: disease activity in psoriatic arthritis; CPDAI: composite psoriatic disease activity index; PsAQoL: psoriatic arthritis quality of life.

Schneeberger EE, personal elaboration.

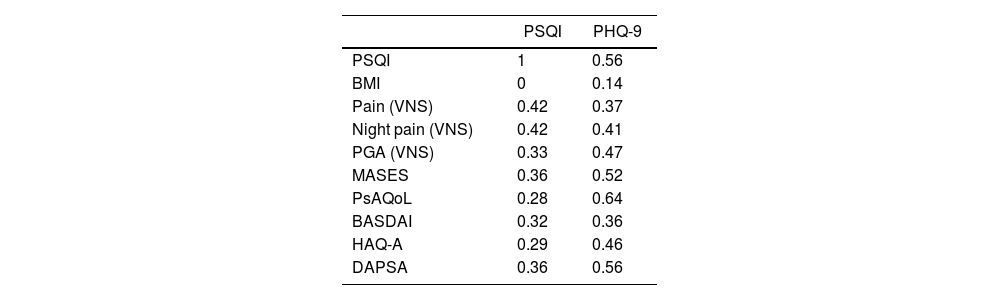

The PSQI had a good correlation with PHQ-9 (Rho: 0.51), regular correlation with pain by VNS (Rho: 0.42) and night pain by VNS (Rho: 0.42). On the other hand, the PHQ-9 had a good correlation with MASES (Rho: 0.52), ASQoL (Rho: 0.59), PsAQoL (Rho: 0.64), and DAPSA (Rho: 0.56) (Table 4).

Correlation* between PSQI and PHQ-9 and clinical characteristics of PsA.

| PSQI | PHQ-9 | |

|---|---|---|

| PSQI | 1 | 0.56 |

| BMI | 0 | 0.14 |

| Pain (VNS) | 0.42 | 0.37 |

| Night pain (VNS) | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| PGA (VNS) | 0.33 | 0.47 |

| MASES | 0.36 | 0.52 |

| PsAQoL | 0.28 | 0.64 |

| BASDAI | 0.32 | 0.36 |

| HAQ-A | 0.29 | 0.46 |

| DAPSA | 0.36 | 0.56 |

PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; BMI: body mass index; VNS: visual numerical scale; PGA: patient global assessment; MASES: Maastricht ankylosing spondylitis enthesitis score; PsAQoL: psoriatic arthritis quality of life; BASDAI: bath ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index; HAQ-A: health assessment questionnaire-Argentinean version; DAPSA: disease activity in psoriatic arthritis.

Schneeberger EE, personal elaboration.

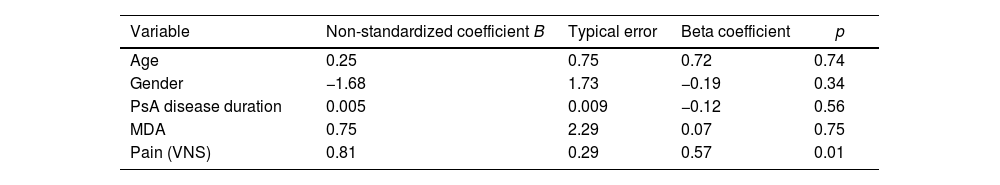

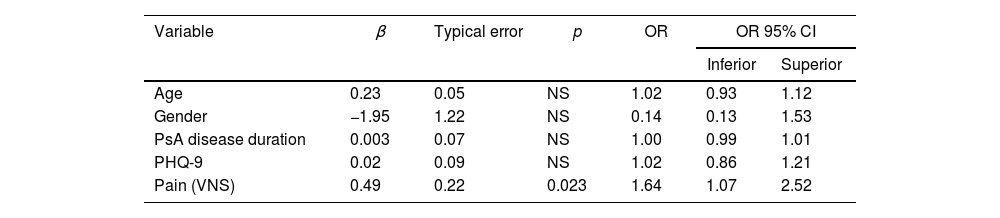

In the multiple linear regression analysis, taking the PSQI result as the dependent variable and adjusting for sex, age and PsA disease duration, pain was independently associated with sleep disorders (Exp β: 0.57, p=0.01). However, in another linear regression model, depression was also associated with sleep disturbances (Exp β: 0.39, p=0.04) (Table 5A and B). In multiple logistic regression, the only variable independently associated with ICSP≥5 was pain (OR: 1.64; 95% CI 1.07–2.52, p=0.023) (Table 6).

Variables associated with sleep disorders. Multiple linear regression.

| Variable | Non-standardized coefficient B | Typical error | Beta coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.25 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.74 |

| Gender | −1.68 | 1.73 | −0.19 | 0.34 |

| PsA disease duration | 0.005 | 0.009 | −0.12 | 0.56 |

| MDA | 0.75 | 2.29 | 0.07 | 0.75 |

| Pain (VNS) | 0.81 | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.01 |

| Variable | Non-standardized coefficient B | Typical error | Beta coefficient | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.68 |

| Gender | −1.66 | 1.41 | −0.19 | 0.21 |

| PsA disease duration | −0.003 | 0.0007 | −0.08 | 0.66 |

| DAPSA | 0.139 | 0.086 | 0.29 | 0.12 |

| PHQ-9 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.39 | 0.04 |

Dependent variable: PSQI result.

PsA: psoriatic arthritis; MDA: minimal disease activity; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; DAPSA: disease activity in psoriatic arthritis; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; VNS: visual numerical scale.

Schneeberger EE, personal elaboration.

Variables associated with sleep disorders. Multiple logistic regression.

| Variable | β | Typical error | p | OR | OR 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | |||||

| Age | 0.23 | 0.05 | NS | 1.02 | 0.93 | 1.12 |

| Gender | −1.95 | 1.22 | NS | 0.14 | 0.13 | 1.53 |

| PsA disease duration | 0.003 | 0.07 | NS | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.01 |

| PHQ-9 | 0.02 | 0.09 | NS | 1.02 | 0.86 | 1.21 |

| Pain (VNS) | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.023 | 1.64 | 1.07 | 2.52 |

Dependent variable: PSQI≥5.

OR: odds ratio; IC: interval confidence; PsA: psoriatic arthritis; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; VNS: visual numerical scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; NS: not significant.

Schneeberger EE, personal elaboration.

In this study, three quarters of the patients in the RAPSODIA cohort presented sleep disturbances and this frequency was significantly higher than controls. It should be noted that six of the seven components of the ICSP questionnaire including duration, disturbances, latency and efficiency of sleep, as well as sleep daytime dysfunction and the need for sleep medication were significantly more frequent in patients than in controls, with the exception of subjective perception of sleep quality. The variable most strongly associated independently with poor sleep quality was pain. These data are consistent with some studies.17,40 However, Strober et al. did not find relationship with pain.15

According to our results, the variable most associated with pain and sleep disturbances was depression. We use a validated and robust questionnaire for this purpose, such as the PHQ-9. More than 50% of our patients had depression and it was also significantly higher in patients than controls. Wu et al. were one of the few studies that measured depression and insomnia in 980 patients with psoriasis and PsA and variables such as age older than 45 years, female sex, presence of comorbidities and psoriatic arthritis were commonly and independently associated with depression and insomnia.41

Other authors also found a relationship between sleep and anxiety,17 but we did not evaluate it in this study. However, in a subsequent study of 100 PsA patients from RAPSODIA cohort, the prevalence of anxiety on the GAD-7 questionnaire was 59%. And both the presence of major depression and anxiety were associated with higher disease activity in patients with PsA.6 Similarly, in this study, patients who did not meet MDA criteria showed higher scores on PHQ-9. However, we did not find association between disease activity and the presence of sleep disturbances. On the contrary, other studies did find a relationship with the presence of arthritis and poorer quality of sleep, in patients with PsA.12,15,18

Fatigue can be both a cause and a consequence of sleep disorders. We did not assess fatigue through a specific self-questionnaire, the median of fatigue by VNS was relatively high (5cm), although with wide variability, and we did not find any association with sleep disturbances.

Although we did not find any difference between genders, Roussou et al. observed both a higher intensity of nocturnal pain and greater sleep disturbances in women versus men with PsA.42

Obesity is also often associated with poor sleep quality, such as obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia43; but in this report, we did not find difference between the BMI of patients with PsA with and without sleep disturbances. These results are in agreement with other reports.12,15,17 In our study, comorbidities were numerically but not significantly higher in patients with PsA compared to controls. Both cardiovascular disease and diabetes are also associated with poor sleep quality44,45; but neither do we find in this case any association. However, we do not rule out that due to the small number of patients, this may be subject to a type 2 error.

Regarding skin involvement, neither PASI nor BSA were associated with poor sleep quality. The results of previous studies show conflicting results. On the one hand, both Wu et al.46 and Strober et al.15 determined that psoriasis is significantly associated with sleep disturbances. And Gowda et al.13 and Shutty et al.14 reported that itching is especially associated with poor sleep quality in patients with psoriasis. While other researchers are in line with our results.17,47

Finally, there is some evidence that anti-TNF agents, especially etanercept and adalimumab, improve sleep quality in patients with psoriasis and PsA.15,19,48,49 Also, a subsequent stratified analysis of the study by Wu et al., detected a more rapid and significant reduction in the frequency of depression and insomnia in patients receiving biologics.41 One possible explanation for this improvement is that elevated plasma levels of TNF-α and its soluble receptors have been detected in patients with acute depression and insomnia, and anti-TNF agents could improve serotonergic/noradrenergic neurotransmission.50 In our study, only 22% of our patients were treated with TNF inhibitors and we found no differences, this could be due to the low number of patients.

This study has some limitations. First, its cross-sectional design does not allow evaluating the direction of the associations found, only a study with a prospective design could do so. Second, the sample size is small and this situation could lead to a type II error, that is, not finding any association when it really exists. And third, we did not evaluate the presence of concomitant fibromyalgia and it has been related to sleep disorders in patients with PsA.51 The main strengths of our study are: its case–control design, which made it possible to detect a higher frequency of disturbances in sleep quality in patients with PsA compared to the general population; the use of a widely validated tool to determine the quality of sleep such as PSQI and the comprehensive clinimetric evaluation in patients with PsA.

ConclusionsPatients with PsA in this cohort presented more frequent sleep disturbances (75%) and depression (55.5%) than controls. Both pain and depression were independently associated with sleep disturbances.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest