Systemic lupus erythematosus is a chronic autoimmune disease with variable severity, neuropsychiatric manifestations comprise a wide spectrum of syndromes defined according to its central and peripheral involvement. Many pathophysiological mechanisms have been involved in the development of these manifestations, such as the disruption of the blood-brain barrier and the cellular toxicity related to autoantibodies such as anti-aquaporin, anti-ribosomal P and anti-phospholipids. Predictive elements to identify neuropsychiatric compromise will be explored by predictive models in this article.

Methodology and methodsRetrospective cross-sectional study, predictive models such as decision trees, naive Bayesian, K-nearest neighbours and generalized linear models were used for the analysis, the best model was selected.

Results122 patients were included, of whom 100 (81.9%) were women and 22 (18.1%) men, the prevalence of neuropsychiatric compromise was 59%, anxiety disorders, headache and mood disorders being the most frequent. In the bivariate analysis, oral ulcers (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.09–6.08 p = 0.02), non-scarring alopecia (OR 4.06, 95% CI 1.76–9.68 p = <0.01), arthritis (OR 2.5, 95% CI 0.99–6.94 p = 0.04), leukopenia (OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.18–7.09 p = 0.04) and patients without accumulated damage measured by the SLICC/ACR-DI damage score (2.1, 95% CI 0.98–4.93 p = 0.01), were associated with greater neuropsychiatric compromise. The best prediction model was the decision tree model, in which non-scarring alopecia, oral ulcers and anti-Ro/SSA antibodies behaved as independent variables related to neuropsychiatric compromise with a precision of 75.6%.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of neuropsychiatric involvement in lupus was 59%, the independent variables that best predict these manifestations were anti-Ro/SSA seropositivity, non-scarring alopecia, and oral ulcers through decision trees.

El lupus eritematoso sistémico es una enfermedad autoinmune crónica con severidad variable, las manifestaciones neuropsiquiátricas comprenden un amplio espectro de síndromes definidos de acuerdo con su compromiso central y periférico. Diversos mecanismos fisiopatológicos tienen relación con el desarrollo de estas manifestaciones, entre los cuales se mencionan la disrupción de la barrera hematoencefálica y la toxicidad celular asociada con autoanticuerpos como antiacuaporina, anti-p ribosomal y antifosfolípidos; aun no se conocen elementos predictores relacionados con la aparición del compromiso neuropsiquiátrico, los cuales se explorarán a partir de modelos de predicción en este trabajo.

Metodología y métodosEstudio analítico retrospectivo de corte transversal; para el análisis se emplearon modelos de predicción a partir de árboles de decisión, bayesiano ingenuo, K vecinos más cercanos y modelos lineales generalizados; se seleccionó el mejor modelo.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 122 pacientes, de los cuales 100 (81,9%) fueron mujeres y 22 (18,1%) hombres, la prevalencia del compromiso neuropsiquiátrico fue del 59%, siendo los trastornos de ansiedad, la cefalea y los trastornos del afecto los más frecuentes. En el análisis bivariado, las úlceras orales (OR 2,52, IC 95% 1,09–6,08 p = 0,02), la alopecia no cicatrizal (OR 4,06, IC 95% 1,76–9,68, p < 0,01), la artritis (OR 2,5, IC 95% 0,99–6,94, p = 0,04), la leucopenia (OR 2,81, IC 95% 1,18–7,09, p = 0,04), así como los pacientes sin daño acumulado medido por el score de daño SLICC/ACR - DI (2,1, IC 95% 0,98–4,93 p = 0,01), se asociaron con mayor compromiso neuropsiquiátrico. El mejor modelo de predicción fue el de árboles de decisión, en el cual la alopecia no cicatrizal, las úlceras orales y el anti Ro/SSA se comportaron como variables independientes relacionadas con el compromiso neuropsiquiátrico, con una precisión del 75,6%.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de compromiso neuropsiquiátrico en lupus fue del 59%, las variables independientes que mejor predijeron estas manifestaciones fueron la seropositividad anti Ro/SSA, la alopecia no cicatrizal y las úlceras orales, por medio de árboles de decisión.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex autoimmune disease, with variable clinical expression and severity.1 Multi-organ involvement is determined by the production of autoantibodies directed against abundant nuclear material and the deposit of immune complexes that lead to the activation of the inflammatory response and underlying tissue damage.2

These changes are influenced by various polygenic variations that confer a predisposition by altering physiological processes such as immune complex clearance and autoreactive B lymphocytes due to C4 and C1q deficiency.3

The neuropsychiatric manifestations of SLE (NPSLE) occur with a variable frequency (between 6–40%) at the time of diagnosis and 17–60% during the disease.4

Multiple pathophysiological mechanisms are related to the development of neuropsychiatric manifestations in subjects with SLE, such as damage to the blood-brain barrier, while the presence of circulating antibodies and disease activity are predisposing factors for the development of these manifestations.5

The presence of antibodies that cause direct cell injury, such as anti-Smith, anti-P ribosomal, or anti-N-methyl-diaspartate receptor (NMDRA), suggests the disruption of the blood-brain barrier through inflammatory mechanisms.6

Anti-NMDRAs cross-react with circulating anti-DNAs that bind to the NR2A and NR2B subunits, leading to neuronal death due to increased calcium influx and excitotoxicity, although these autoantibodies do not directly correlate with neuropsychiatric lupus activity.7

In 1999, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) defined 19 different neuropsychiatric syndromes: 12 involving the central nervous system (CNS) and 7 related to the peripheral nervous system (PNS), of which the former constitutes 75% of the events.8

Our general objective was to explore a predictive model that allows establishing the presence of neuropsychiatric affection in subjects with SLE.

MethodsAn analytical observational study was carried out, with a retrospective collection of cross-sectional data. Patients diagnosed with SLE who met the SLICC 2012 classification criteria, aged 18–60 years, treated in the last 5 years at the Rheumatology and Neurology Service of the Hospital Universitario Clinica San Rafael (Bogota, Colombia) since 2019 were included, which in turn had the measurement of autoantibodies (ANA, anti-Ro/SSA, anti-La/SSB, anti-Sm, anti-RNP, anti-dsDNA, IgG and IgM anticardiolipin, IgG and IgM anti-B2 glycoprotein 1, and lupus anticoagulant).

Patients with overlapping syndromes with other autoimmune diseases and other metabolic disorders were excluded: type 2 diabetes mellitus, adrenal insufficiency, poorly controlled arterial hypertension, liver cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), epilepsy, atherosclerosis, previous ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, consumption of psychoactive substances, neuro infection or other systemic infection, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, HIV, cancer, and treatment with high-dose steroids (0.5−1 mg/kg/day of prednisone). The data recorded in the medical charts were obtained from a database coded with the ICD-10 diagnosis for SLE.

Statistical analysisA non-probabilistic convenience sampling was conducted and the prevalence of neuropsychiatric involvement in SLE was defined from a demographic analysis of the population by age group, to assess the association between neuropsychiatric manifestations and clinical-demographic-serological characteristics, using Fisher's exact test for bivariate analysis, considering a p-value ≤0.05 for the 95% confidence interval (CI) as statistically significant.

Likewise, a generalized linear classification model was developed using neuropsychiatric affection (NPSLE) and the clinical-serological predictor variables included in the database as dependent ones; a binomial distribution with a canonical «logit» function was used. Similarly, the best model was selected by optimizing the AIC coefficient, while to evaluate the prediction of neuropsychiatric involvement, prediction models were explored using decision trees (rpart). To reduce the overfitting, the respective PRUNE and subsequent Bagging were employed, using the Random Forest function. In addition, the error calculation was carried out based on the average error of classification and out-of-bag (OOB). Other models were explored using K nearest neighbors (KNN) and naive Bayesian model, and for the analysis, the software R version 4.0.3 was used. The protocol was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Hospital Universitario Clinica San Rafael (Bogota, Colombia).

Results122 patients were included, of which 100 (81.9%) were women and 22 (18.1%) were men. The evolution time in months (SD) was 41.6 (±4.4) and the age at diagnosis in years (SD) was 39 (±1.5), although there was a higher prevalence in the 20–25 years and 50–55 years treatment groups (see Fig. 1). When calculating the mean of the SLEDAI activity score, the result was 12.5 (±1.0) points for severe flare, while the accumulated damage through SLICC/ACR-DI (SD) was 2.29 (±0.19) points. The estimated prevalence of neuropsychiatric affection (NPSLE) was 59%.

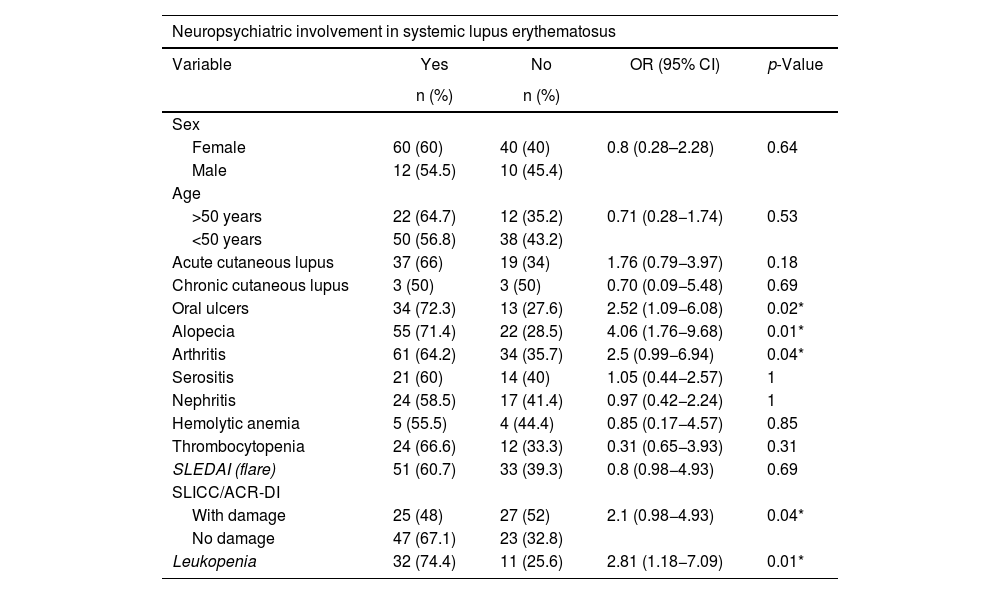

In the bivariate analysis, to assess the association between neuropsychiatric affection and clinical-demographic features, a statistically significant association was demonstrated between the presence of oral ulcers (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.09−6.08; p = 0.02), non-scarring alopecia (OR 4.06, 95% CI 1.76−9.68; p < 0.01), arthritis (OR 2.5, 95% CI 0.99−6.94; p = 0.04), leukopenia (OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.18−7.09; p = 0.04), and individuals without cumulative damage measured by SLICC/ACR-DI (OR 2.1, 95% CI 0.98−4.93; p = 0.01) with greater neuropsychiatric involvement (see Table 1).

Association between clinical variables and neuropsychiatric lupus.

| Neuropsychiatric involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Yes | No | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 60 (60) | 40 (40) | 0.8 (0.28–2.28) | 0.64 |

| Male | 12 (54.5) | 10 (45.4) | ||

| Age | ||||

| >50 years | 22 (64.7) | 12 (35.2) | 0.71 (0.28−1.74) | 0.53 |

| <50 years | 50 (56.8) | 38 (43.2) | ||

| Acute cutaneous lupus | 37 (66) | 19 (34) | 1.76 (0.79−3.97) | 0.18 |

| Chronic cutaneous lupus | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 0.70 (0.09−5.48) | 0.69 |

| Oral ulcers | 34 (72.3) | 13 (27.6) | 2.52 (1.09−6.08) | 0.02* |

| Alopecia | 55 (71.4) | 22 (28.5) | 4.06 (1.76−9.68) | 0.01* |

| Arthritis | 61 (64.2) | 34 (35.7) | 2.5 (0.99−6.94) | 0.04* |

| Serositis | 21 (60) | 14 (40) | 1.05 (0.44−2.57) | 1 |

| Nephritis | 24 (58.5) | 17 (41.4) | 0.97 (0.42−2.24) | 1 |

| Hemolytic anemia | 5 (55.5) | 4 (44.4) | 0.85 (0.17−4.57) | 0.85 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 24 (66.6) | 12 (33.3) | 0.31 (0.65−3.93) | 0.31 |

| SLEDAI (flare) | 51 (60.7) | 33 (39.3) | 0.8 (0.98−4.93) | 0.69 |

| SLICC/ACR-DI | ||||

| With damage | 25 (48) | 27 (52) | 2.1 (0.98−4.93) | 0.04* |

| No damage | 47 (67.1) | 23 (32.8) | ||

| Leukopenia | 32 (74.4) | 11 (25.6) | 2.81 (1.18−7.09) | 0.01* |

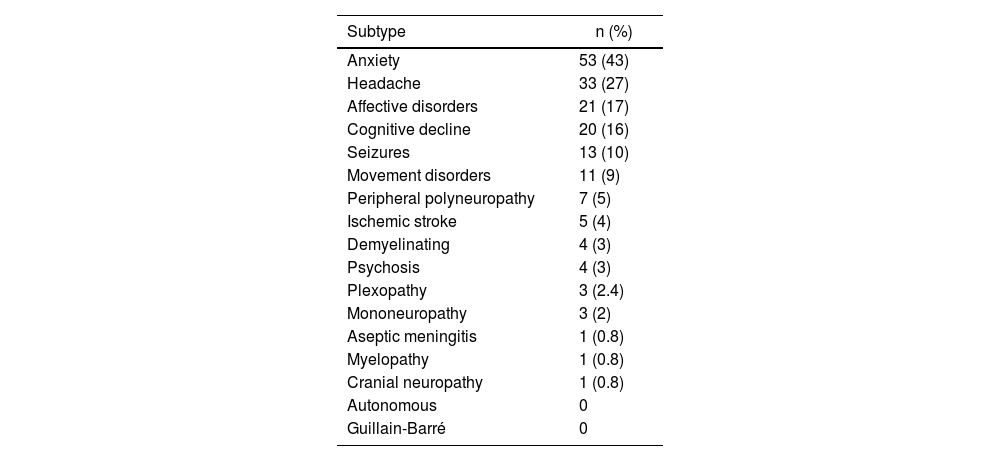

In the group of patients with neuropsychiatric manifestations, it was found that anxiety disorders were the most frequently found (43%), followed by headache (27%) and affective disorders (16%) (see Table 2).

Prevalence of subtypes of neuropsychiatric affection.

| Subtype | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | 53 (43) |

| Headache | 33 (27) |

| Affective disorders | 21 (17) |

| Cognitive decline | 20 (16) |

| Seizures | 13 (10) |

| Movement disorders | 11 (9) |

| Peripheral polyneuropathy | 7 (5) |

| Ischemic stroke | 5 (4) |

| Demyelinating | 4 (3) |

| Psychosis | 4 (3) |

| Plexopathy | 3 (2.4) |

| Mononeuropathy | 3 (2) |

| Aseptic meningitis | 1 (0.8) |

| Myelopathy | 1 (0.8) |

| Cranial neuropathy | 1 (0.8) |

| Autonomous | 0 |

| Guillain-Barré | 0 |

When analyzing the different autoantibodies, despite that most of them were more frequent in the group of subjects with neuropsychiatric affection, none reached statistical significance (see Table 3).

Association between serological variables and neuropsychiatric lupus.

| Variable | NPSLE | NPSLE | OR (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | |||

| Anti-Ro/SSA (+) | 29 (65.9) | 15 (34) | 1.56 (0.68−3.67) | 0.25 |

| Anti-La/SSB (+) | 5 (50) | 5 (50) | 0.67 (0.14−3.11) | 0.73 |

| Anti-Sm (+) | 9 (60) | 6 (40) | 1.0 (0.30−3.84) | 1 |

| Anti-RNP (+) | 14 (77.7) | 4 (22.3) | 2.7 (0.79−12.2) | 0.11 |

| Low C3 | 38 (61.2) | 24 (38.7) | 1.2 (0.55−2.65) | 0.71 |

| Low C4 | 45 (62.5) | 27 (37.5) | 1.4 (0.63−3.14) | 0.37 |

| Anti-DNA | 36 (57.1) | 27 (42.8) | 0.85 (0.38−1.86) | 0.71 |

| IgG anticardiolipin | 16 (66.6) | 8 (33.3) | 1.49 (0.54−4.4) | 0.49 |

| IgM anticardiolipin | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.6) | 2.06 (0.56−9.45) | 0.27 |

| IgG anti-B2 GPI | 13 (68.4) | 6 (31.5) | 1.6 (0.52−5.58) | 0.45 |

| IgM anti-B2 GPI | 9 (69.2) | 4 (30.7) | 1.36 (0.42−7.72) | 0.55 |

| Lupus anticoagulant | 35 (63.6) | 20 (36.3) | 1.41 (0.64−3.5) | 0.36 |

anti-B2 GPI: anti-beta 2 glycoprotein 1; NPSLE: neuropsychiatric lupus.

For the multivariate analysis, different models were explored, as shown below:

Model 1: a generalized linear polynomial classification model with binomial distribution and canonical "logit" function was performed for the dependent variable NPSLE, and it was found that non-scarring alopecia was statistically preserved as an independent variable associated statistically significantly with the presence of neuropsychiatric manifestations, with an AIC value = 186.1. Likewise, to select the best model by maximum likelihood, step forward was used, selecting the model with the lowest AIC, and it was found that the best model to explain the presence of NPSLE retained non-scarring alopecia and antinuclear antibodies as predictor variables, with AIC = 155.8. The mean of the deviance residuals was 0.05, with a variance of 1.17. Similarly, the Pearson residuals behaved with a mean of 0.004 and a variance of 0.97.

Model 2: different prediction models for the dependent variable NPSLE were explored, through the K-nearest neighbors (KNN) model, with K-folds of 10, for cross-validation with the training group and prediction with the test group, selecting for the training group 70% of the data. It was carried out with 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10 neighbors, and a lower average classification error was evidenced with K-vec = 3 by 41%.

Model 3: A naive Bayesian model was developed, assuming the independence of the variables: non-scarring alopecia, oral ulcers, leukopenia, serositis, anti-Ro/SSA, acute/subacute cutaneous lupus, and total SLICC/ACR-DI, which previously demonstrated to be representative in the bivariate analysis concerning NPSLE, and a decrease in the prediction error to 32% was demonstrated, with an accuracy of 68%.

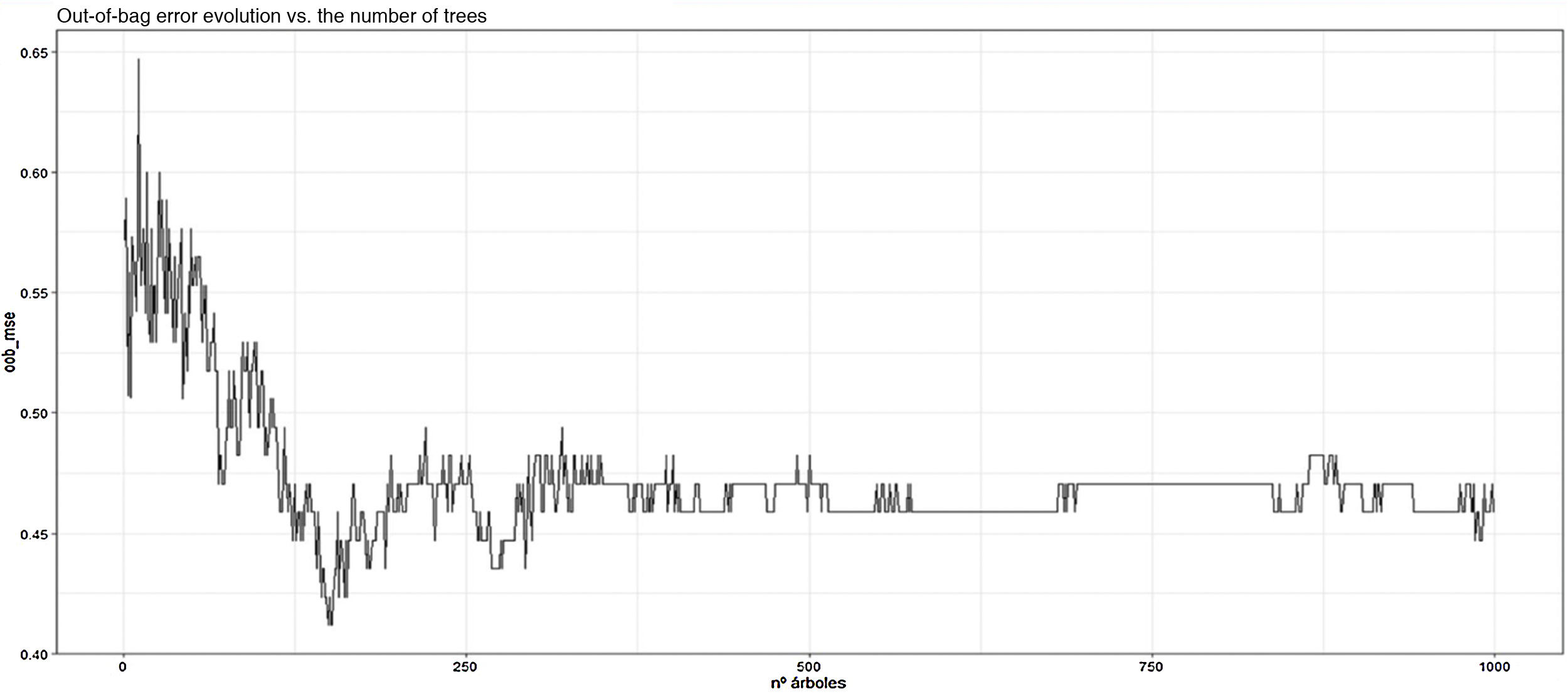

Finally, prediction (model 4) was performed using decision trees using the RPART function, with the dependent variable NPSLE and the predictor variables of the training group, corresponding to 70% of the sample (85 patients), with subsequent prediction versus the training group, and a classification tree with 5 terminal nodes was obtained, taking the variables: non-scarring alopecia, age, total SLICC/ACR-DI, and serositis in order of relevance (see Fig. 2); the precision was 67%. Subsequently, to reduce the error and improve the model, Bagging (model 5) was carried out, through random forest, with 1000 trees and 20 mtry, and the accuracy improved to 75%, with an OOB of 45%.

Additionally, the most important variables related to the reduction of mean classification error and purity were explored (see Fig. 3) and it was shown that the variables that most contributed to the prediction model were again: non-scarring alopecia, oral ulcers, and anti-Ro/SSA. In addition, the reduction of the OOB concerning the number of trees and variables was explored (see Fig. 4) and 25 variables with 750 trees were considered for the new Bagging, without major variation in the OOB or in the accuracy of the model.

With this last model, a precision of 75.6%, a sensitivity of 57%, a specificity of 86%, a PPV of 72%, and a NPV of 76% were obtained.

DiscussionSystemic lupus erythematosus and its neuropsychiatric manifestations have a variable prevalence in the different series explored. In our group of patients, a frequency of 59% was observed, similar to the series described.

Using regression models, the role of autoantibodies in patients with NPSLE has been previously assessed and a significant association of Q albumin, anti-Sm, and the acute confusional syndrome has been described in patients with diffuse neuropsychiatric involvement. This confirms a significant contribution of the anti-Sm (p = 0.004), but not of the anti-NR2 (p = 0.50), the anti-P ribosomal (p = 0.26), or the anticardiolipin antibodies (p = 0.67) in the presence of elevated Q albumin.9

In contrast to our research, from the exploration of the important variables, according to the reduction of the mean error of classification and the Gini index, the importance of anti-Ro/SSA as a predictive element was evidenced. Likewise, regarding the association of anti-Ro/SSA and neuropsychiatric lupus, at the University of Maryland, in the period 1992–2003, a cohort of 130 patients was evaluated, of which 66 developed neuropsychiatric manifestations related to the presence of this antibody in multivariate models. In this case, there was an adjusted OR of 2.2 (1.0–7.9), a p-value = 0.020, and an age-adjusted OR of 1.7 (0.8–23.9), with a p = 0.016,10 like our findings in the decision tree models, in which anti-Ro/SSA was found to be an important variable in terms of mean classification error reduction.

Additionally, the presence of the Ro/SSA antibody has been identified in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neuropsychiatric lupus. In this sense, Mevorach et al. compared serum and cerebrospinal fluid Ro/SSA antibody titers and found that these were found in a low proportion at the level of the central nervous system.11

In our setting, a systematic review was conducted on serological markers associated with neuropsychiatric manifestations, whereas a strong relationship with antiphospholipid, anti-P ribosomal, and anti-NMDA12 antibodies is described.12

In our series, when exploring the subtypes of neuropsychiatric affection, it was found that anxiety (43%) and affective (17%) disorders were the most frequently found. In other series, Nery et al. explored the association of depressive disorders and anxiety with the presence of anti-P ribosomal antibodies, and it was observed that affective and anxiety disorders were found in 26.8% and 46.5%, respectively, without finding a significant association with the anti-P ribosomal antibodies.13

In this context, the suicide attempt in the scenario of the patient with SLE was explored as a neuropsychiatric expression. Karasa et al. reported 7 episodes in 5 patients over 20 years and demonstrated the presence of positive serum anti-Ro/SSA in 3 of them, following the same line of association with the marker that was seen in our study.14

In addition to the above, in a study that included 522 subjects, with a female preponderance, it was shown that antibodies such as anti-Ro/SSA60 were observed in a greater proportion in the NPSLE group (33.5%); however, compared to patients without NPSLE, it does not reach statistical significance (p = 0.65).15

With reference to disorders related to seizures and headaches, in our cohort, there were found in 10% and 27%, respectively. In contrast, in the Seth et al.15 cohort, convulsive events are described as the main manifestation of neuropsychiatric lupus, with a presentation of 41.3% of the individuals, while headache reached 9.6%, comparable to Brey et al.16 and Hanly et al.17

The strengths of this study are the use of different useful prediction techniques in a homogeneous population and the fact that it is the first study on the prediction of neuropsychiatric manifestations in our setting. The greatest weakness is its retrospective nature and, by including only one center as an acute care hospital, most patients with high disease activity were explored, with the biases that this may represent in this research regarding the greater associated inflammation.

This research serves as a starting point to continue exploring predictive elements in prospective cohort studies with larger samples. It is essential to consider the associated factors that can predict neurological events, due to the negative impact that they have on the functional and social capacity of the individuals who suffer from them, as well as to select the most appropriate treatment with an adequate risk-benefit balance.

ConclusionsA 59% prevalence of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus was estimated, where anxiety and headache were the most frequently found variables. Non-healing alopecia, oral/nasal ulcers, arthritis, leukopenia, and SLICC/ACR-DI were significantly associated with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus in bivariate analysis. When exploring a generalized linear model, it was observed that non-scarring alopecia is retained as an independent variable that is associated with neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus in the selection of the model with the lowest AIC.

Non-scarring alopecia, oral ulcers, anti-Ro/SSA seropositivity, and leukopenia/lymphopenia were the most important variables for predicting neuropsychiatric affection using decision trees, with an accuracy of 75% (95% CI 0. 58−0.88), moderate sensitivity (57%) and high specificity (86%). These variables are more useful for ruling out the entity in those who do not present them, as well as a good predictive power regarding positive and negative predictive values (72% and 76%, respectively).

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in this article.