The evaluation of clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients, including the patient's perspective, allows the inclusion of the patient's perspective in clinical decision-making using instruments designed for this purpose.

ObjectiveTo identify and describe the instruments validated in Spanish to evaluate clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis in daily clinical practice and from the patient's perspective, including disease activity, functionality, impact of the disease, adherence to treatment and quality of life.

Materials and methodsA review of the literature in various databases (PubMed, Scopus, Bireme, Scielo) was conducted looking for questionnaires that evaluate clinical outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients, including those with a validated Spanish translation that allow self-assessment of the disease by the patient and clinical monitoring.

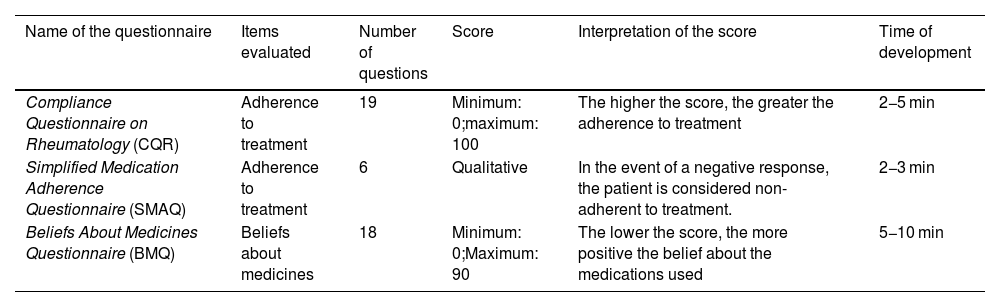

ResultsFifteen questionnaires were identified and selected that met the inclusion criteria. Four instruments were found that evaluate quality of life, three that evaluate functionality, four that evaluate disease impact, one that evaluate disease activity, and three that evaluate adherence to treatment.

ConclusionQuestionnaires and scales that evaluate rheumatoid arthritis allow a clinical approach to the evolution of the disease as perceived and reported by the patients, optimizing clinical follow up. Implementation of these tools in clinical decision making allows for an improvement in quality of care of patient with this condition.

La evaluación de desenlaces clínicos en pacientes con artritis reumatoide, considerando la perspectiva del paciente, permite la inclusión del concepto del paciente en la toma de decisiones clínicas mediante la utilización de instrumentos diseñados para tal fin.

ObjetivoIdentificar y describir los instrumentos validados en castellano para evaluar desenlaces clínicos en artritis reumatoide en la práctica clínica diaria y desde la perspectiva del paciente, incluyendo la actividad de la enfermedad, la funcionalidad, el impacto de la enfermedad, la adherencia al tratamiento y la calidad de vida.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó una búsqueda de artículos relacionados con la evaluación de desenlaces clínicos en artritis reumatoide. Se revisaron las siguientes bases de datos: PubMed, Scopus, Bireme y Scielo, en busca de instrumentos o cuestionarios autoadministrados, que tengan traducción validada al castellano y permitan la evaluación y monitorización clínica.

ResultadosSe identificaron y seleccionaron 15 cuestionarios que cumplen los criterios de inclusión. Se encontraron 4 instrumentos que evalúan la calidad de vida, 3 que valoran la funcionalidad, 4 que evalúan el impacto de la enfermedad y un instrumento que evalúa la actividad de la enfermedad. Así mismo, se reportan 3 instrumentos que evalúan la adherencia al tratamiento.

ConclusiónLos cuestionarios y las escalas de evaluación en artritis reumatoide permiten ofrecer una aproximación clínica de la evolución de la enfermedad percibida y reportada por los pacientes, con lo cual se optimiza el seguimiento clínico. La implementación de estas herramientas en la toma de decisiones permitirá mejorar la calidad de la atención de estos pacientes.