Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is a vasculitic disease with an infrequent involvement of the central nervous system. This can lead, in rare cases, to hypertrophic pachymeningitis (HP), which is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis that cause a thickening of dura mater. At present, it is crucial to consider GPA in the differential diagnosis of elderly patients with intracranial hypertension. The case is presented of a 60-year-old male with progressive severe headache, vomiting, and wasting syndrome. Physical examination showed pallor, weight loss, and unilateral papilloedema. A gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI scan showed sinusitis, chronic otomastoiditis, and hypertrophic pachymeningitis. Finally, a meningeal biopsy concluded a necrotising granulomatous vasculitis compatible with GPA. However, PR3- and MPO-ANCA were negative. After corticosteroid therapy was initiated, the patient had a favorable outcome during his hospital stay.

La granulomatosis con poliangeítis (GPA) compromete excepcionalmente el sistema nervioso central, conllevando en raras ocasiones a una paquimeningitis hipertrófica (PH), caracterizada por inflamación y fibrosis, que originan un engrosamiento de la duramadre. Actualmente, su consideración es crucial en el diagnóstico diferencial de pacientes ancianos con hipertensión endocraneana. Presentamos el caso de un adulto de 60 años con cefalea severa progresiva, vómitos, papiledema unilateral y síndrome consuntivo en donde la resonancia magnética cerebral contrastada con gadolinio muestra sinusitis, otomastoiditis y PH. Finalmente, la biopsia de meninges reveló vasculitis granulomatosa necrosante de pequeños y medianos vasos compatible con GPA. Empero, PR3− y MPO-ANCA resultaron negativos. Se inició terapia con corticoides, presentando una evolución clínica favorable durante su hospitalización.

Granulomatosis with poliangiitis (GPA), formerly known as Wegener's granulomatosis, is a necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis that mainly affects small- to medium-sized vessels.1 The incidence rate is nearly 7–10 cases per million people per year,2 being more frequent in the 64–74years-old range. GPA usually involves the upper respiratory tract, lower respiratory tract and kidneys; however, it may affect any other system such as neurological.3 It has been usually associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), specifically targeted to proteinase 3 (c-ANCA), although sometimes they may be negative, especially when is limited to some organs.

Neurological involvement in GPA is observed in 22–54% of patients, who mainly develop peripheral nervous system involvement.4,5 However, the central nervous system involvement is not common (<10%), presenting as ischemic stroke, cerebral hemorrhage and granulomas in the brain, spinal cord, pituitary or meninges,6 as well as hypertrophic pachymeningitis (HP), a chronic fibrosing inflammation of the dura matter characterized by a diffuse or local thickening.7

HP may be idiopathic or secondary to other diseases, such as tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, IgG4-related disease, syphilis, fungal diseases, lymphoma, etc.8,9 Therefore, accurate and timely etiological diagnosis is a significant challenge in clinical practice. We present a report of a patient with GPA with chronic otitis media, sinusitis, mastoiditis, hypertrophic pachymeningitis and negative ANCA.

Case descriptionA 60-year-old Peruvian patient with a 3-month history of global oppressive headache. One month before admission, headache intensity was increasing gradually in association with nausea, vomiting, hyporexia and asthenia. Then, one week before he came to the emergency room because the intensity of the headache became worse, altering sleep and with concomitant projectile vomiting with very poor oral tolerance. The patient had lost 20kg over these three months. He had a history of Type II Diabetes Mellitus for 8 years, but with an irregular treatment with metformin, and also had a right lower jaw abscess 25 years ago.

On arrival to the emergency room, he looked cachectic weighing 44kg. His blood pressure was normal with mild tachycardia. Physical examination showed a marked pallor, fat tissue depletion, a right neck scar of 1cm and cataract in the right eye. He had no heart murmurs, and respiratory examination was normal. The patient was oriented in time, space and person; without any meningeal signs or focal deficits. Fundus examination revealed left papilledema. Rest of physical examination was unremarkable.

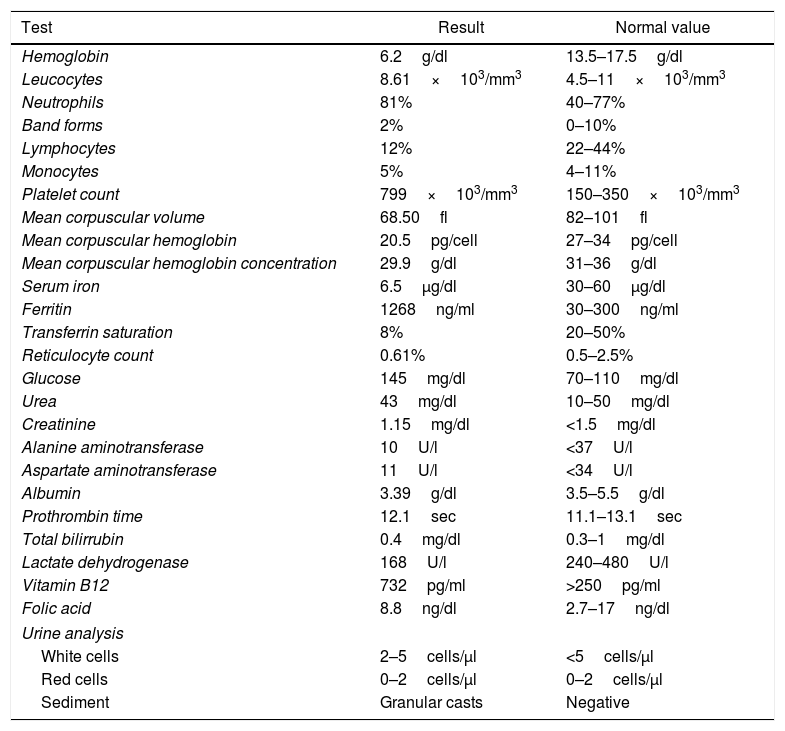

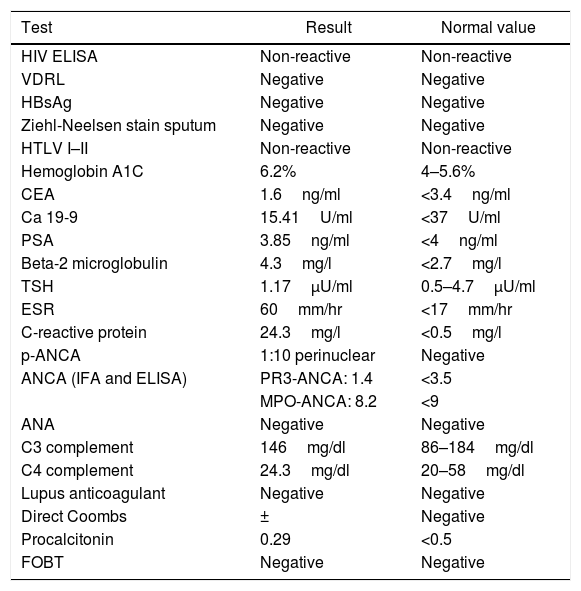

Laboratory results showed severe anemia with characteristics corresponding to anemia of chronic disease. Additional lab tests were performed (Table 1).

Laboratory results.

| Test | Result | Normal value |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 6.2g/dl | 13.5–17.5g/dl |

| Leucocytes | 8.61×103/mm3 | 4.5–11×103/mm3 |

| Neutrophils | 81% | 40–77% |

| Band forms | 2% | 0–10% |

| Lymphocytes | 12% | 22–44% |

| Monocytes | 5% | 4–11% |

| Platelet count | 799×103/mm3 | 150–350×103/mm3 |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 68.50fl | 82–101fl |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin | 20.5pg/cell | 27–34pg/cell |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration | 29.9g/dl | 31–36g/dl |

| Serum iron | 6.5μg/dl | 30–60μg/dl |

| Ferritin | 1268ng/ml | 30–300ng/ml |

| Transferrin saturation | 8% | 20–50% |

| Reticulocyte count | 0.61% | 0.5–2.5% |

| Glucose | 145mg/dl | 70–110mg/dl |

| Urea | 43mg/dl | 10–50mg/dl |

| Creatinine | 1.15mg/dl | <1.5mg/dl |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 10U/l | <37U/l |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 11U/l | <34U/l |

| Albumin | 3.39g/dl | 3.5–5.5g/dl |

| Prothrombin time | 12.1sec | 11.1–13.1sec |

| Total bilirrubin | 0.4mg/dl | 0.3–1mg/dl |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | 168U/l | 240–480U/l |

| Vitamin B12 | 732pg/ml | >250pg/ml |

| Folic acid | 8.8ng/dl | 2.7–17ng/dl |

| Urine analysis | ||

| White cells | 2–5cells/μl | <5cells/μl |

| Red cells | 0–2cells/μl | 0–2cells/μl |

| Sediment | Granular casts | Negative |

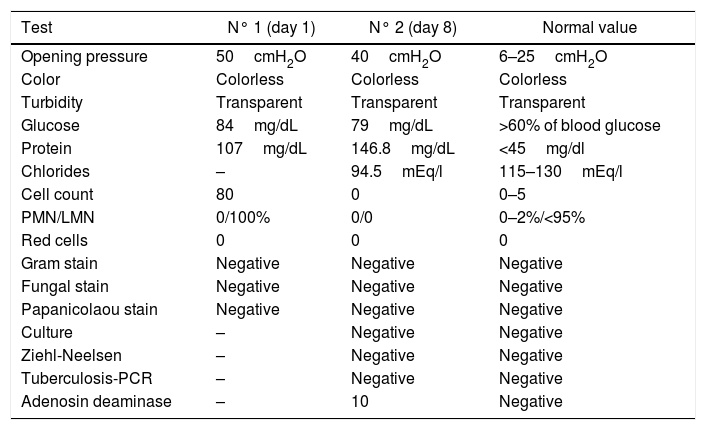

Computed tomography (CT) of the head was performed during hospitalization, in order to complete study of intracranial hypertension, however no significant findings were found. The first day, a lumbar puncture was accomplished, revealing a high opening pressure (50cm H2O), mild pleocytosis and elevated proteinorrachia (Table 2). After one week, another lumbar puncture was performed with high opening pressure (40cm H2O) and high CSF protein level persisted; glycorrachia, Gram staining, Chinese ink and CSF-ADA were within normal range. In addition, Papanicolaou staining, culture, Ziehl–Neelsen staining and polymerase chain reaction for TBC were negative (Table 2).

CSF analysis.

| Test | N° 1 (day 1) | N° 2 (day 8) | Normal value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opening pressure | 50cmH2O | 40cmH2O | 6–25cmH2O |

| Color | Colorless | Colorless | Colorless |

| Turbidity | Transparent | Transparent | Transparent |

| Glucose | 84mg/dL | 79mg/dL | >60% of blood glucose |

| Protein | 107mg/dL | 146.8mg/dL | <45mg/dl |

| Chlorides | – | 94.5mEq/l | 115–130mEq/l |

| Cell count | 80 | 0 | 0–5 |

| PMN/LMN | 0/100% | 0/0 | 0–2%/<95% |

| Red cells | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gram stain | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Fungal stain | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Papanicolaou stain | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Culture | – | Negative | Negative |

| Ziehl-Neelsen | – | Negative | Negative |

| Tuberculosis-PCR | – | Negative | Negative |

| Adenosin deaminase | – | 10 | Negative |

PMN, polymorphonuclear, LMN, lymphomononuclear.

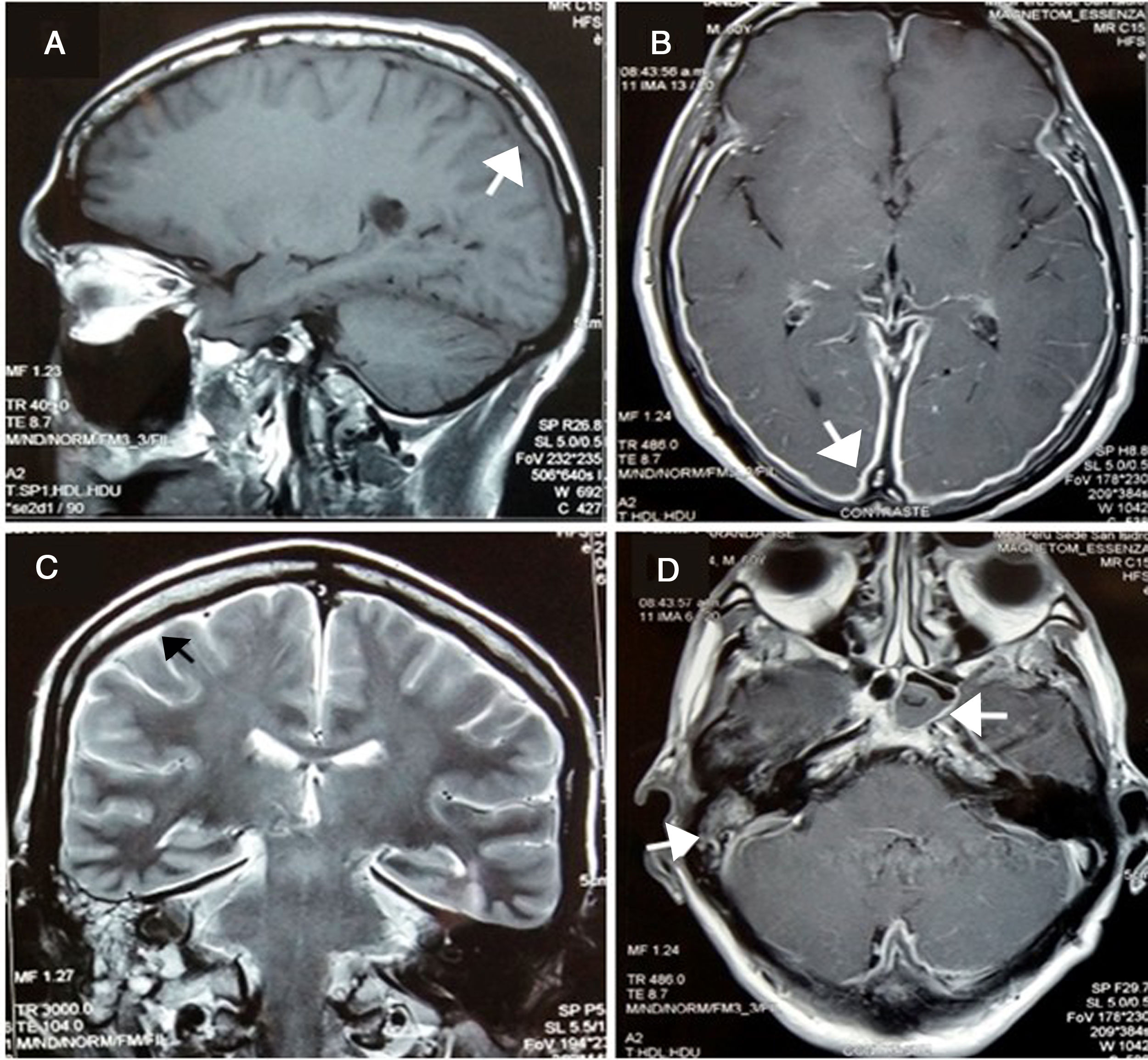

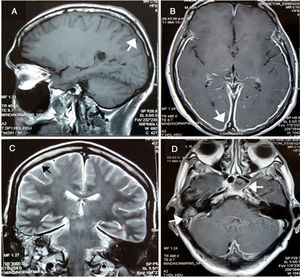

After two weeks, he began presenting progressive involvement of the III and VI cranial nerves and purulent nasal discharge was present. Gadolinim-enhaced brain MRI was performed showing fluid in mastoid air cells, right middle ear and left sphenoid sinus. In addition, it showed dura mater thickening and an increased contrast uptake in the pachymeninges in botch cerebral convexity and cerebellar tentorium (Fig. 1), these findings were compatible with diffuse hypertrophic pachymeningitis, left sphenoid sinusitis and right chronic otomastoiditis. No relevant findings were found in thoracoabdominal CT. At that time, several laboratory tests were performed in order to reach the underlying etiological diagnosis of the HP (Table 3).

(A) Pachymeningeal thickening in non-contrast MRI (B and C) Diffuse enhancement dural thickening in cerebral convexity and cerebellar tentorium consistent with pachymeninigitis in T1- and T2-weighted MRI (arrows). (D) Axial MRI shows right otomastoiditis and left sphenoid sinusitis (arrows).

Laboratory results.

| Test | Result | Normal value |

|---|---|---|

| HIV ELISA | Non-reactive | Non-reactive |

| VDRL | Negative | Negative |

| HBsAg | Negative | Negative |

| Ziehl-Neelsen stain sputum | Negative | Negative |

| HTLV I–II | Non-reactive | Non-reactive |

| Hemoglobin A1C | 6.2% | 4–5.6% |

| CEA | 1.6ng/ml | <3.4ng/ml |

| Ca 19-9 | 15.41U/ml | <37U/ml |

| PSA | 3.85ng/ml | <4ng/ml |

| Beta-2 microglobulin | 4.3mg/l | <2.7mg/l |

| TSH | 1.17μU/ml | 0.5–4.7μU/ml |

| ESR | 60mm/hr | <17mm/hr |

| C-reactive protein | 24.3mg/l | <0.5mg/l |

| p-ANCA | 1:10 perinuclear | Negative |

| ANCA (IFA and ELISA) | PR3-ANCA: 1.4 | <3.5 |

| MPO-ANCA: 8.2 | <9 | |

| ANA | Negative | Negative |

| C3 complement | 146mg/dl | 86–184mg/dl |

| C4 complement | 24.3mg/dl | 20–58mg/dl |

| Lupus anticoagulant | Negative | Negative |

| Direct Coombs | ± | Negative |

| Procalcitonin | 0.29 | <0.5 |

| FOBT | Negative | Negative |

HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; VDRL, venereal disease research laboratory; HBsAg, Australia antigen; HTLV, human T-lymphotropic virus; CEA, carcynoembrionic antigen; Ca, cancer antigen; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; PR3-ANCA, proteinase 3 anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; MPO-ANCA, myeloperoxidase anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody; ANA, antinuclear antibody; FOBT, fecal ocult blood test.

Peripheral blood smear was performed in parallel, in order to approach the anemia, although it did not show significant alterations. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy found an erythematous gastritis, non-specific duodenitis and candida esophagitis; and colonoscopy revealed dolichocolon and grade I internal hemorrhoids. In addition, fecal occult blood test was negative. A bone marrow biopsy showed extensive deposits of interstitial mucin with hematopoietic elements and cellularity in 20%. These findings were compatible with a degeneration or gelatinous transformation of bone marrow (GTBM), a considerably rare entity that is associated with microcytic anemia and severe consumption.

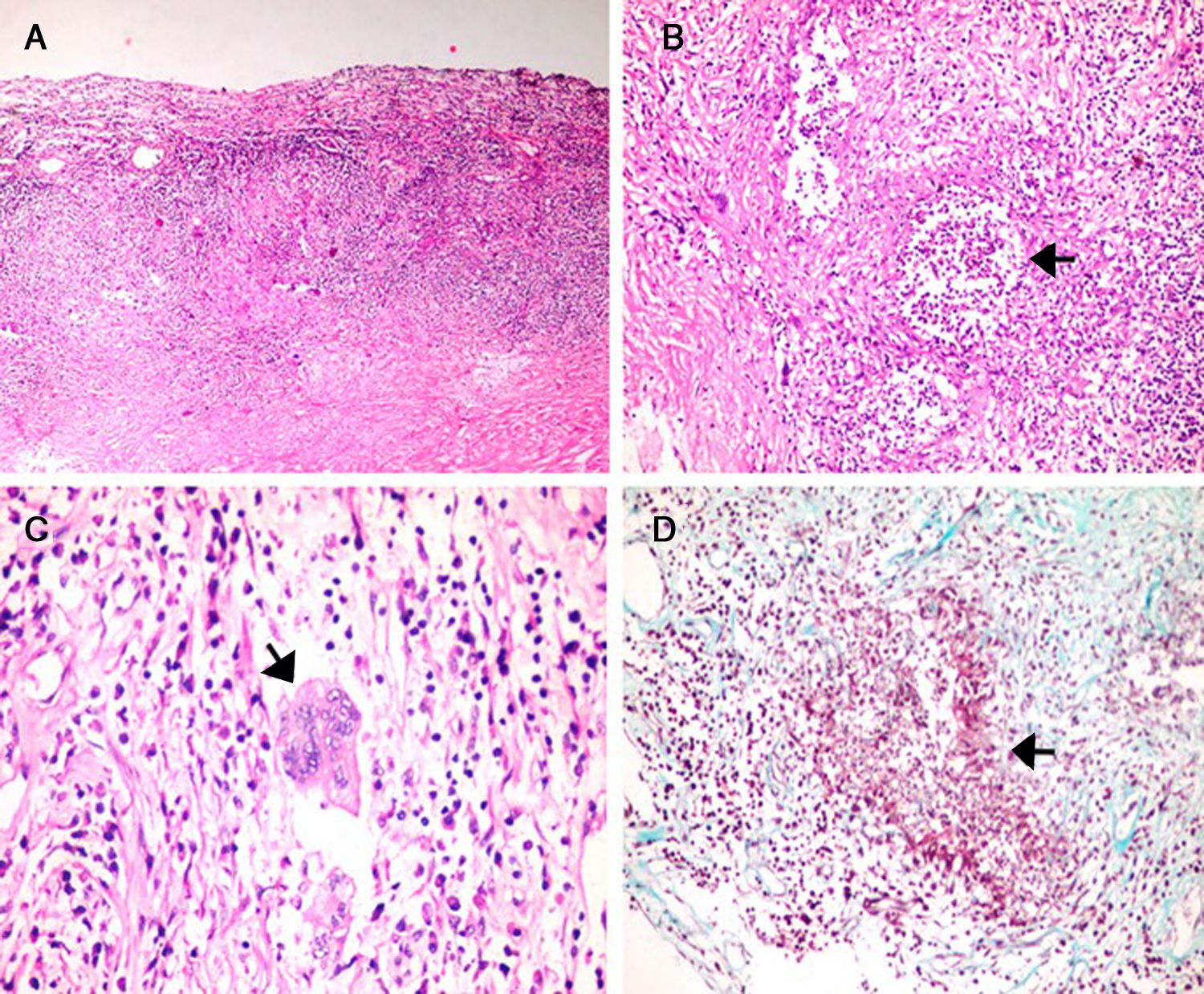

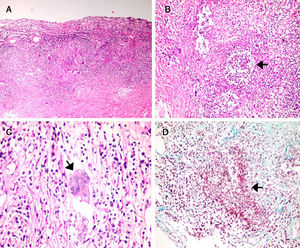

ANCA was also tested by indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) and ELISA, however, both ANCA results directed to proteinase3 (c-ANCA): 1.4 (NV: <3.5) and myeloperoxidase (p-ANCA): 8.2 (NV: <9) were negative. The patient persisted with headache despite the use of analgesics. A meningeal biopsy was performed after 3 weeks and histopathological findings (Fig. 2) showed thickened and fibrotic meninges, with an extensive and diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate as well as areas of necrosis. Likewise, malformed granulomas with multinucleated giant cells and microabscesses were found. Additionally, inflammatory infiltrate reached the wall of small and medium caliber arteries. No pseudohyphae or fungal spores were recognized; Ziehl–Neelsen, Periodic acid–Schiff and Masson's trichrome stainings were negative. No neoplastic cells were observed. Immunohistochemical staining for IgG4 was negative. Then, these findings were compatible with a definitive diagnosis of necrotizing granulomatous pachimeningitis due to vasculitis of small and medium vessels.

(A) H&E stain. Thickened dura mater with extensive lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate. (A–C) Granulomatous areas with microabcesses, necrosis and multinucleated giant cells (Langhans-type). (D) Masson's trichrome stain shows inflammatory infiltrate in smooth muscle vessel wall (red) with surrounding fibrotic areas (blue).

Finally, based on upper respiratory tract compromise and meningeal histopathology, diagnosis of hypertrophic pachymeningitis due to GPA with a negative ANCA was reached. Treatment with prednisone 1mg/kg (per day) for three weeks was then initiated considering the deteriorated patient's condition and a high probability of sepsis. He had a considerable improvement of the clinical course and was discharged. Unfortunately, he came to the emergency room after seven days due to septic shock and died one day after admission.

DiscussionHypertrophic pachymeningitis (HP) is a rare fibrosing inflammatory disease that encompasses focal or diffuse thickening of the dura mater, causing progressively a neurological deficit in some cases. Clinical symptoms and signs of this entity are due to the entrapment of cranial nerves, dural venous sinuses or cerebrospinal fluid obstruction and rarely owing to brain artery occlusion.7,10 Our patient presented symptoms of intracranial hypertension with a late involvement of the third and sixth cranial nerves, which has been reported as a complication of pachymeningitis.

The etiology of HP is extremely diverse, hence, it constitutes a true diagnostic challenge and a timely management is imperative to avoid complications. It is essential to differentiate the primary or idiopathic form from secondary causes such as infections (tuberculosis, syphilis, cysticercosis, mycosis, IgG4-related disease, Lyme disease, HTLV-I), neoplasms (meningeal carcinomatosis, lymphoma, meningioma), immunological diseases (rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus) and miscellaneous such as hemodialysis, intracranial hypotension, intracranial administration of drugs.11,12 Such entities were ruled out during the case history. Consequently, GPA diagnosis was based on the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria1: nasal inflammation with purulent discharge due to paranasal sinus involvement and chronic otomastoiditis corroborated by magnetic resonance, as well as the histopathology of meninges were compatible with necrotizing granulomatous vasculitis of small and medium vessels.

CNS vasculitis includes inflammation and destruction of cerebral and/or spinal cord vessels, presenting an incidence of 2.4 cases per million people.13 Meningeal involvement in GPA is an unusual variety, with a frequency of 1%. Nishino et al. reported that only 2 of 324 patients with GPA had presented HP.5 Several studies indicate that the pathogenic mechanism is likely to be the invasion of granulomatous tissue present in nasal or paranasal cavities to contiguous structures, such as meninges and cranial nerves.5,14,15 Furthermore, it is possible that CNS involvement mostly occurs in late stages of GPA cases, or the meningeal involvement may be associated to localized form of GPA,16 as in the present case.

In 1990, GPA diagnosis criteria were established by the American College of Rheumatology, among which the involvement of upper airways and granulomatous inflammation in biopsy, were present in our patient. The c-ANCA (PR3-ANCA) is not included as a diagnostic criterion,17 since at that time its significance as a diagnostic tool was not established, being currently a considerably sensitive and specific marker for systemic GPA but not for localized GPA. In a Di Committee cohort, ANCA was positive in 52% of patients with localized GPA and in 86% of patients with generalized disease.18

In our study, the patient had a localized compromise of GPA in middle ear, mastoid, sphenoid sinus and predominantly meningeal, initially visualized by gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI and subsequently corroborated by meningeal biopsy, where a necrotizing granulomatous infiltrate of small- and medium-sized vessels compatible with GPA was found, however, both MPO-ANCA and PR3-ANCA were negative. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends that in the absence of positive ANCA, the diagnosis of small vessel vasculitis such as GPA should not be ruled out.19 On the other hand, the Chapel Hill Consensus Conference20 suggests that in an ANCA negative vasculitis, there could be an undetectable ANCA with current methods or an ANCA not yet discovered or a low ANCA activity in the pathogenic mechanisms.

Symptoms of upper tract involvement such as rhinosinusitis or otitis media are the most common initial manifestations in up to 75% of GPA cases. Yokoseki21 found a high frequency of patients with lesions limited to dura mater and upper respiratory tract that developed headache, chronic sinusitis, otitis media or mastoiditis. However, it would be associated with positive MPO-ANCA as opposed to a positive PR3-ANCA that would mostly indicate a systemic compromise of GPA.

On the other hand, during the evaluation of severe anemia, bone marrow biopsy was performed and an interesting finding was the gelatinous transformation of bone marrow (GTBM). This is a very rare clinicopathological entity with hypoplasia of the bone marrow, fat atrophy and deposit of gelatinous matter.22 It is also a marker of serious disease and is generally associated with severe malnutrition due to anorexia, as in the present case. Sen et al.23 studied 65 cases of GTBM in which 100% had anemia being mostly severe, which agrees with our patient, who had a severe multifactorial anemia by chronic disease and GTBM. In patients older than 60 years, it is linked to carcinoma, chronic heart failure and lymphomas,24 however this is the first report in which GTBM and GPA concur.

Currently, HP is being increasingly recognized with neuroimaging techniques as brain CT or MRI, however, the former has lower sensitivity and specificity for detecting meningeal disease than gadolinium-enhanced brain MRI, hence, the latter is the preferred method for early recognition diagnosis of HP, requiring focal or diffuse thickening (>2mm) and dura mater enhancement on T1-weighted contrast-enhanced brain MRI.3,25

Reports suggest that the treatment of HP due to GPA should include a high dose of corticosteroids associated with cyclophosphamide or methotrexate,18,21 however there is still no consensus established. We chose to avoid cyclophosphamide on account of bone marrow hypoplasia, severe malnutrition and immunodeficiency of the patient. Corticotherapy alone was effective during hospitalization with a favorable outcome.

ConclusionIn the approach to elderly patients with a recent-onset progressive headache associated with vomiting and also cranial nerve involvement, the differential diagnosis should include HP due to vasculitis as GPA, even in the absence of a positive ANCA. We also recommend contrast-enhanced brain MRI as an indispensable tool to reach a timely diagnosis of HP.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.