Limp and lower limb pain are a frequent cause of consultation in pediatrics. Among the differential diagnoses we must include osteochondrosis, a self-limiting disorder that arises due to avascular necrosis of the ossification centres, in which radiology is the key to diagnosis. The case submitted illustrates the imaging findings of osteonecrosis of tarsal navicular, medial and intermediate cuneiform in a child.

La cojera y el dolor de miembro inferior son una causa frecuente de consulta en pediatría. Entre los diagnósticos diferenciales debemos incluir las osteocondrosis, que son un grupo de trastornos autolimitados que surgen de la necrosis avascular de los núcleos de osificación, en cuyo diagnóstico es clave la radiología. El caso presentado ilustra los hallazgos por imagen de la osteonecrosis del navicular, cuña medial e intermedia en un niño.

Osteochondrosis represents a group of self-limited disorders resulting from osteonecrosis of the ossification centers in skeletally immature patients,1 which have been described in the entire human skeleton in more than 50 anatomical sites.2,3 Köhler’s disease or avascular necrosis of the navicular bone or tarsal scaphoid is a rare entity, which is included within the osteochondrosis of growth.4 We present the case of a child with osteonecrosis of the navicular, medial and intermediate cuneiform bone.

Clinical caseA four-year-male patient, with no personal history of interest, who attended the emergency department due to a limp of one week of evolution. The initial examination revealed referred pain at rotation of the left ankle, with discrete edema and erythema of the dorsal region and sole of the foot. A C-reactive protein (CRP) of 2.47 mg/dL stood out in the laboratory analysis and the rest of the tests were normal. X-ray and ultrasound of the foot were performed, which resulted normal, therefore, the patient was sent home with suspicion of reactive arthritis.

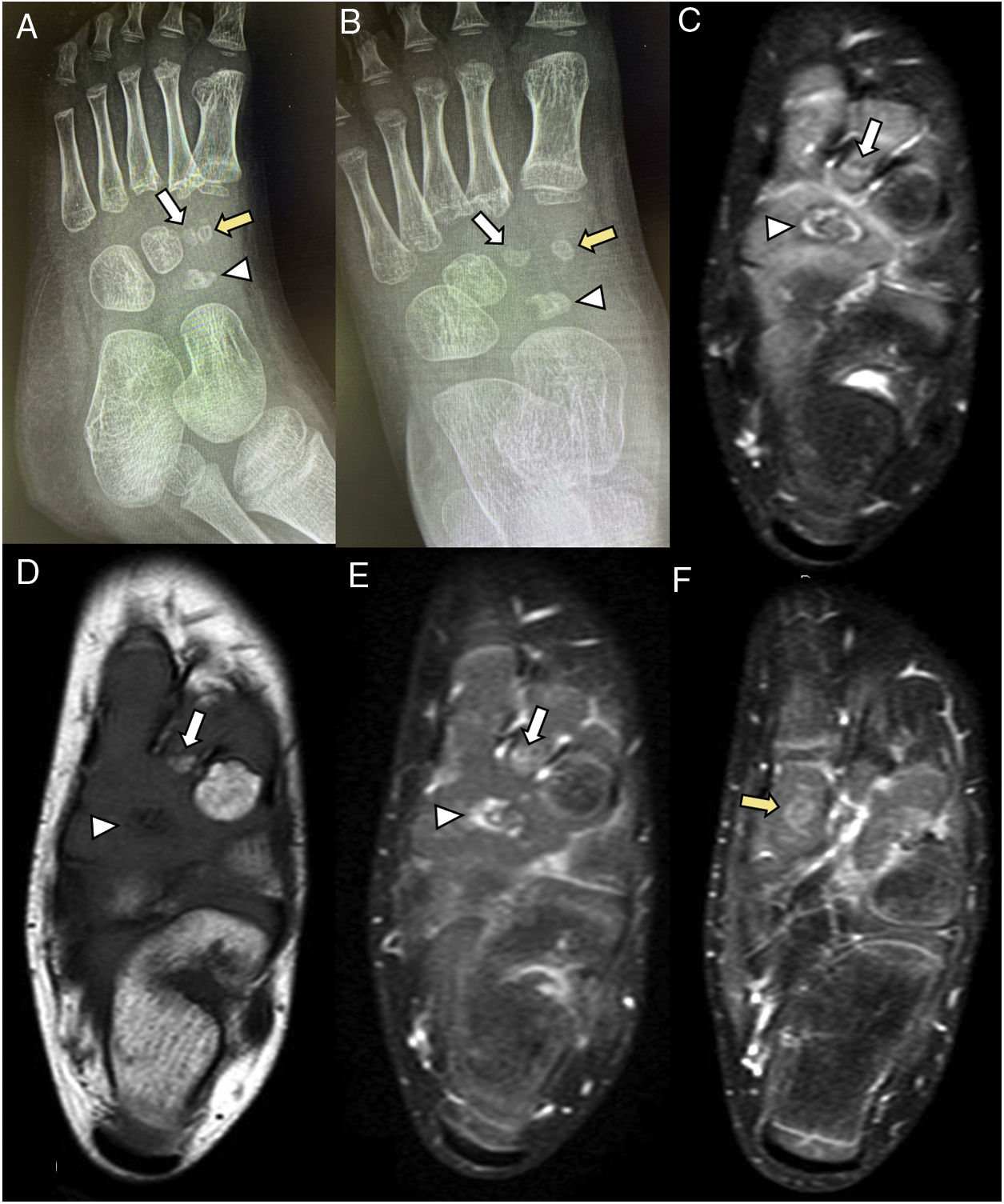

The patient returned again two months later for worsening, with rejection to ambulation and resting the foot on the floor, so the X-ray of the foot was repeated, evidencing a decrease in size and irregularity of the ossification nucleus of the navicular, medial and intermediate cuneiform bone, with partial collapse of the former (Fig. 1A and B); the study was expanded with a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without and with intravenous contrast, which showed T1 hypointensity of the navicular bone and intense enhancement in the periphery after the administration of the contrast media, with similar changes in the cuneiforms (Fig. 1C–F), compatible with osteonecrosis.

Standing X-rays and MRI without and with intravenous contrast.

Navicular (arrow head), medial cuneiform (yellow arrow), intermediate cuneiform (white arrow).

A) Oblique lateral and B) anteroposterior radiograph of the foot showing a decrease in size, sclerosis, and irregularity of the ossification centers of the medial, intermediate cuneiform and the navicular bone, with partial collapse of the latter.

C) T2-weighted axial sequence with fat suppression that confirms and details the findings described in the radiograph, a more marked collapse of the lateral aspect of the navicular, with hyperintense border on its periphery and in the intermediate cuneiform is evidenced.

D) T1-weighted axial sequence. A marked decrease in the signal intensity of the navicular and a discrete decrease in the intermediate cuneiform are observed.

E) and F) T1-weighted sequences with fat suppression after the administration of IV contrast. There is evidence of intense enhancement in the periphery of the navicular bone, as well as in the medial and in the intermediate cuneiform, related to reactive hyperemia.

Limp and pain in the lower limb are frequent musculoskeletal manifestations in children.5 In the differential diagnosis we must include osteochondrosis, being the tarsal scaphoid and the head of the second metatarsal bone the most commonly affected in the foot.3,6 Osteochondrosis are caused by a temporary disruption of the blood supply to the bone-cartilage complex, which leads to osteonecrosis.7,8 Multiple etiological factors that could contribute to the development of this disorder have been proposed, including repeated microtrauma, rapid growth, genetic and hormonal factors,7,8 as well as coagulopathies and passive smoking.6

Navicular osteonecrosis, also known as Köhler’s disease, can be bilateral in up to 25%,5,8 it is more frequent in children (80%),8 typically between four and six years of age.2,9 The scaphoid is the tarsal bone that takes the longest time to ossify,1,2 which make it especially susceptible to compression-induced damage.2 Osteochondrosis of the cuneiforms are rare, being the medial cuneiform the most frequently affected,2,3 followed by the intermediate.3

Since the symptoms and physical examination are nonspecific, imaging tests are needed to reach the diagnosis. Plain radiography is the first test to perform, that can show bone sclerosis, irregularity and fragmentation,5,9,10 collapse of the lateral aspect of the navicular bone10 and medial and dorsal subluxation of its medial aspect9 in more advanced stages. MRI images show areas of low signal intensity in weighted sequences both in T1 and T2 in the bone marrow, with increased enhance in the bone periphery after the administration of IV contrast, indicative of reactive hyperemia.9,10

This condition is self-limited, most patients present a clinical recovery between two weeks and four months,3 however, the resolution of radiographic abnormalities can be delayed up to four years since the onset of symptoms.9

Our case, a clear example that in this pathology the clinical and analytical findings are non-specific, highlights the importance of imaging tests to reach a diagnosis. It is necessary to know what the typical radiological manifestations previously described may be.

Several cases of osteonecrosis of the navicular or cuneiform bones in children have been described in the literature, but we have only found one in which both locations occurred in the same patient,2 hence the relevance of the case that we present.

At the time of this publication, five months after the onset of the clinical picture, the patient is asymptomatic and no further imaging studies have been performed.

ConclusionsOsteochondrosis is a group of self-limiting disorders in which radiological evaluation is the fundamental test; they must be included in the differential diagnosis of lower limb pain.

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that informed consent from the patient to participate in the work described was requested. Since this study did not involve any invasive therapeutic or diagnostic intervention on the patient, it was not necessary to request authorization from the Ethics Committee of the institution.

FundingThis research has not received any specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector, or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.