Fragility fractures are a frequent complication of osteoporosis and lead to increased morbidity and mortality, as well as decreasing quality of life of the elderly population, and represents high costs for health care systems. After minor trauma, fractures of the femoral neck, distal radius, proximal humerus, and thoraco-lumbar vertebrae are associated with osteoporosis, and are considered fragility fractures.

ObjectiveTo identify the prevalence of risk factors in people over 50 years of age with fragility fractures treated at a third level hospital in the department of Boyacá, Colombia.

MethodologyObservational, descriptive, retrospective cross-sectional study. An evaluation was made on 242 patients between 50 and 100 years of age with any of the previously mentioned 4 fragility fractures. Fracture diagnosis had to be confirmed by plain radiography or computed tomography.

ResultsThe majority (62.8%) of the study population was female. Age was associated with an increase in the number of femur fractures. A history of previous fractures was observed in 10.7% of the cases, with prevalence increasing with age. Distal radius fracture was the most frequent in 36.8% of the population. About 40% of the patients had hypertension and 7.9% were diabetic. Chronic use of Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) was observed in 9.7%, and 2.4% consumed glucocorticoids prior to the event.

ConclusionsThe behaviour of fragility fractures of the population in our institution is similar to that of other places, both nationally and internationally. It is therefore important to start raising awareness about secondary prevention of osteoporosis, in order to reduce complications, improve outcomes, and reduce associated costs.

Las fracturas por fragilidad son una complicación frecuente de la osteoporosis y generan alto impacto en la calidad de vida del adulto mayor. Las fracturas de cuello femoral, radio distal, húmero proximal y vértebras toracolumbares, en el contexto de un traumatismo menor, se consideran fracturas por fragilidad.

ObjetivoIdentificar la prevalencia de factores de riesgo en personas mayores de 50 años con fracturas por fragilidad atendidas en un hospital del departamento de Boyacá.

MetodologíaEstudio observacional, descriptivo y de corte transversal. Se incluyeron 242 pacientes que presentaron fracturas por fragilidad con diagnóstico confirmado por estudio imagenológico.

ResultadosEl 62,8% de la población fue femenina. La edad condiciona un aumento del número de fracturas de fémur. El 10,7% de la población tenía un antecedente de fractura, con un aumento de la prevalencia a mayor edad. La fractura de radio distal fue la más frecuente en el 36,8% de la población. Cerca del 40% de los pacientes era hipertenso y el 7,9% tenía diabetes, en tanto que el 9,7% era consumidor crónico de inhibidores de la bomba de protones. El 2,4% consumía glucocorticoides previamente al evento.

ConclusionesEl comportamiento poblacional de las fracturas por fragilidad en nuestra institución es similar al de otros lugares, tanto a escala nacional como internacional. Por tanto, es importante empezar a crear conciencia sobre la prevención secundaria de la osteoporosis, con el fin de disminuir las complicaciones, mejorar los desenlaces y disminuir los gastos que consigo trae.

Osteoporosis is the primary bone tissue disease around the world, characterized by low mineral density which leads to deterioration of the tissue microarchitecture, increased bone fragility and increased risk of fractures.1,2 This pathology is mostly associated with age, with an increasing lineal relationship: the older the individual, the higher the probability of developing fractures.2–4 Gender also plays an important role, since the incidence of osteoporosis is higher in females as compared to males. It has been found that the differences in pre-puberal growth, in addition to the characteristics of the endocrine system in each gender, condition these differences between males and females.5,6

Contrary to the old beliefs, during the first decade of the 21st Century, Riggs et al. described trabecular bone loss in women aged between 21 and 50 years, representing approximately one third of the trabecular bone loss over the lifetime of a woman.7 Subsequently, with menopause and the decline in estradiol levels, a rapid phase of cortical and trabecular bone loss is initiated and perpetuated as years go by.8 There are as well some modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol abuse and a sedentary lifestyle. Secondary causes such as endocrine, gastrointestinal, hematological and multiple genetic diseases, as well as the chronic use of certain medications, also increase the risk of developing the disease.9–11

One of the main issues of osteoporosis is the long-term complications, such as fragility fractures, defined as «any fracture resulting from an event that usually would not result in a fracture in a healthy subject». In other words, secondary to minor trauma, defined as falls from standing height or even shorter.2 All fractures due to osteoporosis are considered fragility fractures, until proven otherwise.3,12

In 2016, according to the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), there were approximately 8.9 million fractures per year, secondary to osteoporosis. 80% of them were nor studied or diagnosed.13 Warriner et al. conclude that fractures of the femoral neck, distal radius, proximal humerus and thoraco-lumbar vertebrae, are the most commonly associated with osteoporosis. Currently, these sites are defined as fragility fractures.2

García et al. conducted a costs analysis in Colombia and concluded that the surgical management cost of a fracture is around COP $2.319,111 up to $11.348,379, depending on the affected bone structure. Furthermore, they estimated the average cost of making the diagnosis of osteoporosis, at around COP $828,969.50, considering laboratory tests, bone scan, and outpatient visits for one year.11

There are multiple useful tools in clinical practice to quicky and easily assess the risk of fractures during a visit to the doctor. Some examples are: Osteoporosis Risk Assessment Instrument (ORAI), Osteoporosis Index of Risk (OSIRIS), Simple Calculated Osteoporosis Risk Estimation (SCORE).14 The most widely used tool in Colombia is the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), which has been validated for our population,15 and provides the best accuracy for the characteristics of the population. Unfortunately, quite often these tools are not frequently used in the clinical practice of the general practitioner.

Consequently, considering the high frequency of this pathology, its economic impact, the reduced function and disability it generates, and with a view to learn about the local epidemiology of the region, the decision was made to conduct a study to determine the presence of risk factors in individuals aged 50 and older, who sustained fragility fractures and were treated at a third level hospital in Boyacá, Colombia, in order to establish prevention, diagnostic and timely treatment measures in patients with osteoporosis.

Materials and methodsAn observational, descriptive, cross-sectional, retrospective study was conducted, including patients between 50 and 100 years old, diagnosed with a fracture of the femoral neck, the distal radius, the proximal humerus, or a thoraco-abdominal vertebra, during the period between January 1st and December 31st, 2019.

The search was done based on the medical records from the hospital files, identified with the respective International Classification of Diseases (CIE-10). The study included all adult patients between 50 and 100 years old, who were admitted to the Hospital San Rafael de Tunja with one of the four classical fragility fractures, as determined by the findings and the reports of the radiographic or CT imaging studies (femoral neck, distal radius, proximal humerus and thoraco-lumbar vertebral fractures). Patients with incomplete medical records, active neoplasms, multiple trauma, acetabular osteophyte or a history of other diseases that could affect the bone structure, other than osteoporosis, were excluded.

The study variables included demographics, sex, age and origin. Patients were also asked about any comorbidities, history of osteoporosis, osteopenia, fractures or use of medications, type of fracture, trauma mechanism, length of stay, and whether any laboratory tests or bone scans were requested during hospitalization.

One of the researchers collected the data from February 1st through February 28th, 2020. A data collection form was developed to enter the above-mentioned variables. The information of the patients who met the inclusion criteria was recorded in an Excel database, version 2013 and was analyzed using the statistical software SPSS version 22.0. The univariate analysis was conducted with descriptive statistics of the selected population, establishing absolute and relative frequencies in the categorical variables. In the case of quantitative variables, the central tendency measures (mean, median) and the dispersion measures (standard deviation and interquartile range) were estimated, based on variable distribution.

Study biasesThere may be some selection biases in this study, therefore the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the participating population were defined. Another potential bias is information, and therefore the data were collected buy one researcher who had the data collection form available to ensure that all the variables were complete.

Ethical considerationsBased on Resolution 8430 of 1993, that establishes the rules for health-related research, the corresponding authorization was requested from the ethics committee of the hospital, which is the custodian and the body in charge of patient information. All the ethical and biomedical standards required by the ethics committee were met.

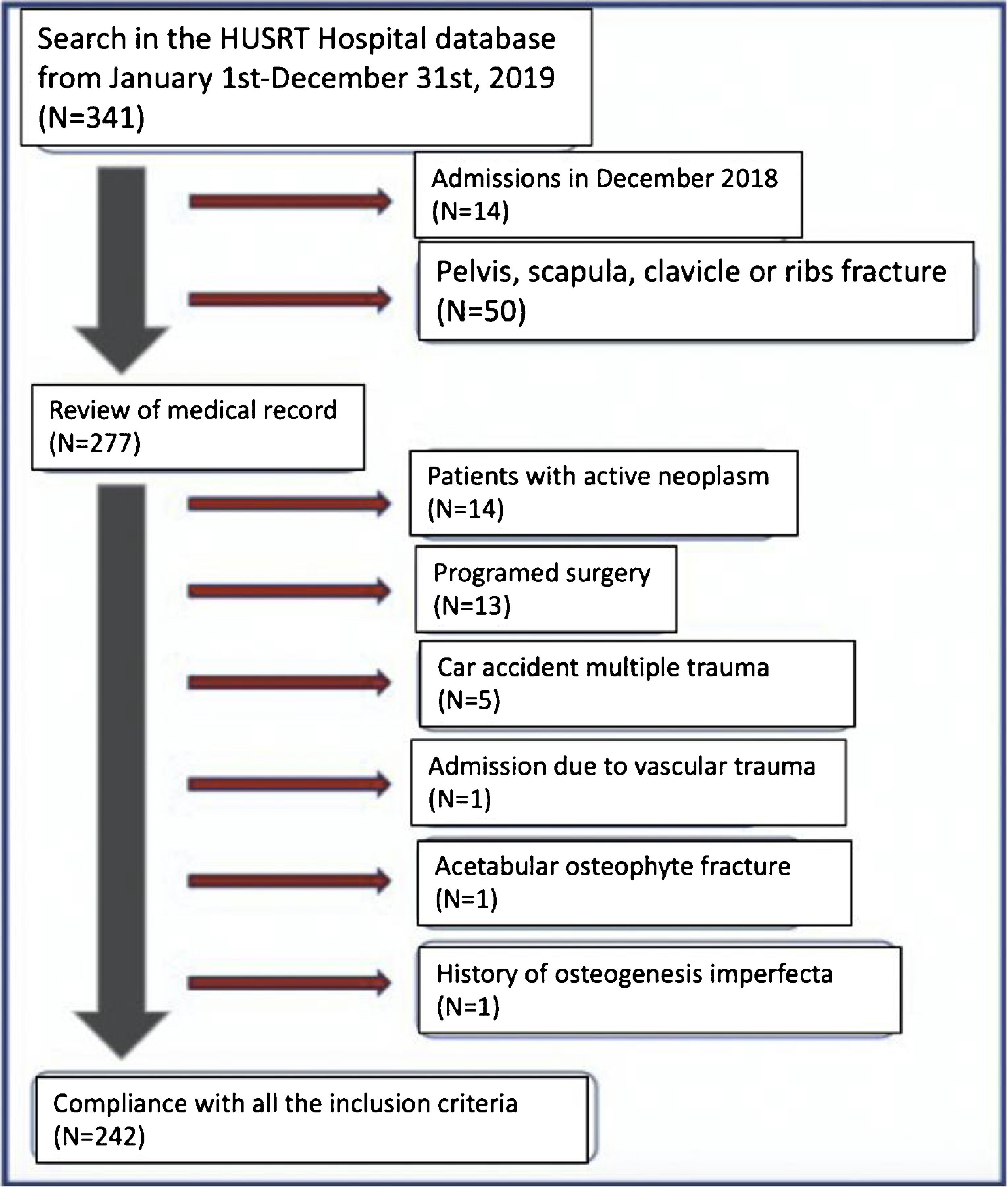

ResultsNumber of participants and selectionDuring the study period, the emergency department admitted a total of 341 patients between 50 and 100 years old, who were suspicious of sustaining a fragility fracture. 14 patients who came to the institution in December 2018, and 50 patients with fractures in anatomical sites different from those established in the study (pelvis, scapula, clavicle or rib) were not taken into account.

The review of the remaining 277 medical records excluded another 35 patients, 14 of which had active neoplasm, 13 were admitted for programmed surgery, 5 experienced trauma as a result a traffic accidents, one was referred to vascular surgery, one had an acetabular osteophyte fracture, and one had a history of osteogenesis imperfecta.

Finally, the study comprised 242 records of patients who met the established inclusion criteria and were analyzed in this study. Fig. 1 summarizes the participants selection process.

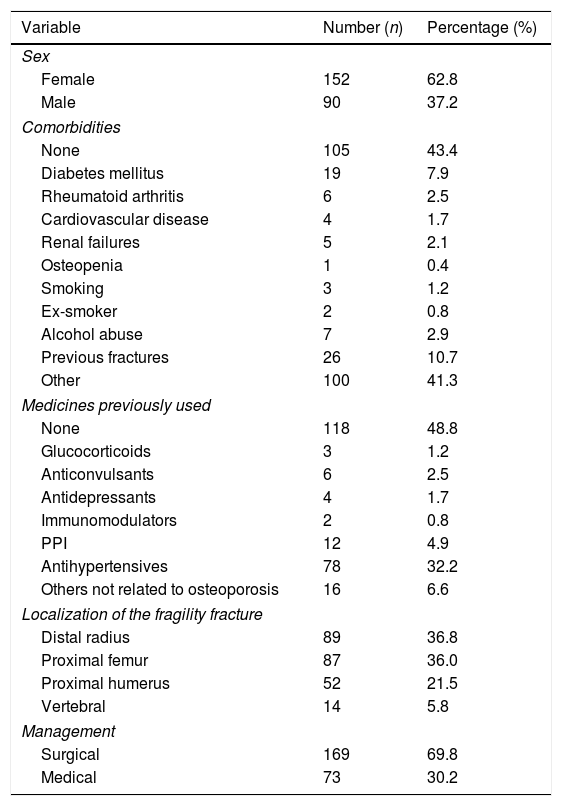

Sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of risk factorsA total of 242 people participated in the study, 62.8% females and 37.2% males. The mean age was 71.4 years (SD±11.97 years).

With regards to comorbidities associated with osteoporosis, 7.9% of the patients had a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus type 2, 2.5% had a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, and 2.1% had renal failure.

Before the event, about 50% did not take any drugs. 32.2% of the patients received at least one antihypertensive, 4.9% required proton pump inhibitors (PPB), and 1.2% was on glucocorticoids.

10.7% of the patients reported one previous fracture before the event and 2.9% reported alcohol abuse. Table 1 shows the risk factors and their prevalence.

Demographic characteristics and risk factors for osteoporosis.

| Variable | Number (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 152 | 62.8 |

| Male | 90 | 37.2 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| None | 105 | 43.4 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 19 | 7.9 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 6 | 2.5 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 4 | 1.7 |

| Renal failures | 5 | 2.1 |

| Osteopenia | 1 | 0.4 |

| Smoking | 3 | 1.2 |

| Ex-smoker | 2 | 0.8 |

| Alcohol abuse | 7 | 2.9 |

| Previous fractures | 26 | 10.7 |

| Other | 100 | 41.3 |

| Medicines previously used | ||

| None | 118 | 48.8 |

| Glucocorticoids | 3 | 1.2 |

| Anticonvulsants | 6 | 2.5 |

| Antidepressants | 4 | 1.7 |

| Immunomodulators | 2 | 0.8 |

| PPI | 12 | 4.9 |

| Antihypertensives | 78 | 32.2 |

| Others not related to osteoporosis | 16 | 6.6 |

| Localization of the fragility fracture | ||

| Distal radius | 89 | 36.8 |

| Proximal femur | 87 | 36.0 |

| Proximal humerus | 52 | 21.5 |

| Vertebral | 14 | 5.8 |

| Management | ||

| Surgical | 169 | 69.8 |

| Medical | 73 | 30.2 |

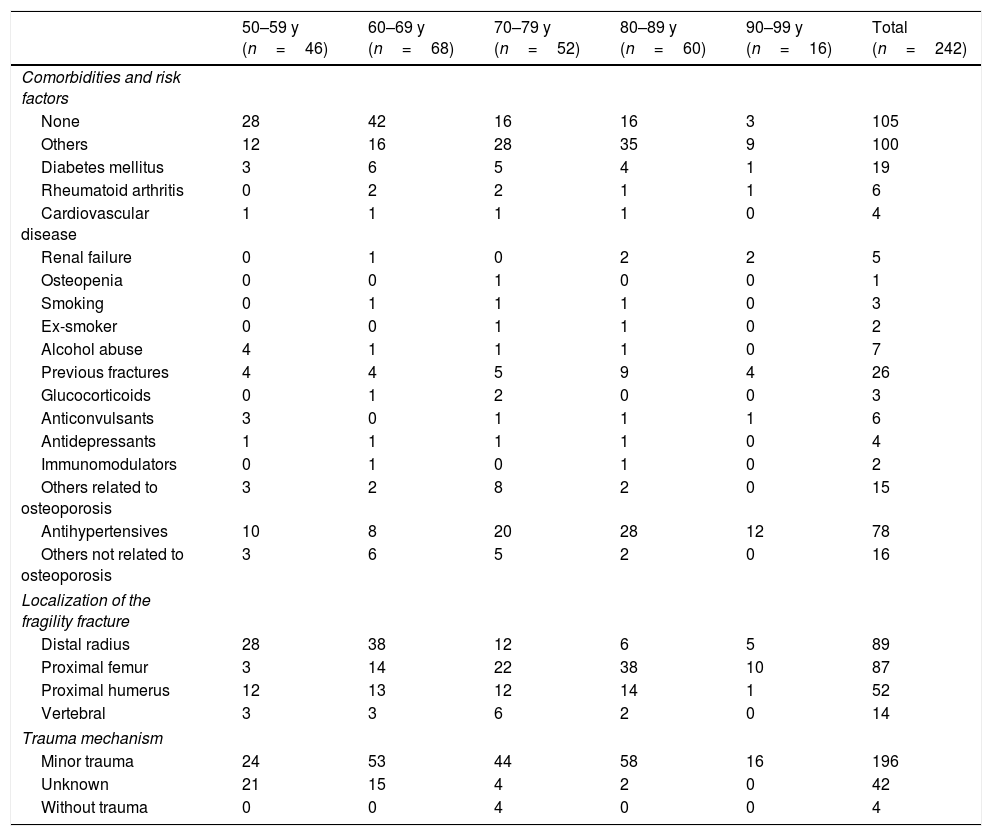

The distal radius fracture was the most frequent fragility fracture out of the four types of fractures studied, with a prevalence of 36.8% in our population and it presented most often in patients aged 50–70. The fracture of the proximal femur was present in 36% of the patients, mostly between 60 and 90-year old. Table 2 shows the prevalence of risk factors for each age group.

Prevalence of risk factors by age group.

| 50–59 y (n=46) | 60–69 y (n=68) | 70–79 y (n=52) | 80–89 y (n=60) | 90–99 y (n=16) | Total (n=242) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities and risk factors | ||||||

| None | 28 | 42 | 16 | 16 | 3 | 105 |

| Others | 12 | 16 | 28 | 35 | 9 | 100 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 19 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Renal failure | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Osteopenia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Smoking | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Ex-smoker | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Alcohol abuse | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Previous fractures | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 26 |

| Glucocorticoids | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Anticonvulsants | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Antidepressants | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Immunomodulators | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Others related to osteoporosis | 3 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 15 |

| Antihypertensives | 10 | 8 | 20 | 28 | 12 | 78 |

| Others not related to osteoporosis | 3 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 16 |

| Localization of the fragility fracture | ||||||

| Distal radius | 28 | 38 | 12 | 6 | 5 | 89 |

| Proximal femur | 3 | 14 | 22 | 38 | 10 | 87 |

| Proximal humerus | 12 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 1 | 52 |

| Vertebral | 3 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| Trauma mechanism | ||||||

| Minor trauma | 24 | 53 | 44 | 58 | 16 | 196 |

| Unknown | 21 | 15 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 42 |

| Without trauma | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

Over 60% of the population studied were females; this finding is consistent with the normal behavior of osteoporosis according to the literature,11,12,14–16 given the close relationship of this disease with menopause-associated estrogen depletion.5,6

According to the age groups, there were 68 events of fractures in patients between 60 and 69 years old and 60 events in the group between 80 and 89 years old. In the first age group, 38 fractures were of the distal radius – the most affected site –, while in the second group the most affected site was the proximal femur. This pattern of presentation is consistent with the findings by Kanis et al., who found that in the Swedish, English and American populations, the distal radius fractures are more frequent among people aged 50–70 years. These results also evidence that the older the patients, the higher the prevalence of proximal femur fractures.17 In our population, most of the events were due to falls from standing height.

2.9% of the patients reported alcohol abuse in their medical record, which is a lower prevalence as compared to the 2013 survey, which reported that 11.4% of the population in Boyacá had a behavioral risk of alcohol abuse, mostly among young patients.18 The low rate recorded could be due to the population studied and to under-registration in the medical records.

Among the causes for secondary osteoporosis, medicines such as PPIs and glucocorticoids are included. In our study, 9.7% of the patients were chronic PPI users and 2.4% used glucocorticoids. The chronic use of PPIs inhibits the gut absorption of vitamin D and calcium.19 Moreover, glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis is multifactorial. In addition to inhibiting the production, proliferation, maturation and osteoblast function via IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) block, glucocorticoids produce osteoprotegerin inhibition (principal bone resorption inhibitor). Moreover, glucocorticoids have been found to upregulate RANK-L (receptor activator for nuclear factor κ B ligand), an osteoclastogenesis mediator, which reduces the formation of new bone.20,21

The study found that 10.7% of the population had at least one previous fracture. According to Toth et al., women with a history of fracture have 28.5% increased risk of sustaining a new hip fracture, 20.4% humerus fracture, and 14.1% increased risk of experiencing a vertebral fracture.9 Our findings were consistent with the literature reports,8,9 with increasing percentages based on age. 8.7% of the population between aged between 50 and 60 had a previous fracture, while of those aged between 80 and 90, the percentage increased to 15% and up to 25% for those between 90 and 99 years old. These findings confirm the direct relationship between age and the risk of experiencing any type of fractures.

With regards to the use of medications, 1.2% were chronic corticoid users and this risk has been described as dose-dependent. Van Staa et al. found that the RR of hip fracture was 1.77 with doses between 2.5 and 7.5mg/day, and of 2.27 with higher doses; while for vertebral fractures, the risk was 2.59 and 5.18 with same doses, respectively.21 Moreover, PPIs increase the risk of developing fragility fractures, with a dose-dependent risk. The study by Targownik et al. found that the exposure for 7 years or more to these drugs was associated with an increased global risk of fracture, with an OR of 1.92.22

Polypharmacy is another risk factor conditioning falls in the elderly population.23 In the study population, around 40% of the patients were hypertensive before experiencing the fracture, and 32% were receiving antihypertensive treatment. Though this aspect is beyond the scope of this study, antihypertensive therapy has been associated with hypotension events that may give rise to falls and subsequent fractures, particularly in the elderly.24

In 2000, the estimated number of fragility fractures worldwide was approximately 9 million, while in 2010, a total of 5.2 million fragility fractures were recorded in only 12 industrialized countries in América, Europe and the Pacific region.25 In response to this worldwide problem, in 2012 the IOF developed a worldwide program called «Capture the Fracture».26 This program establishes the standards for good practice for the detection and secondary prevention of fragility fractures. The laboratory tests required for assessment are calcium, vitamin D and PTH.27 However, the requirements for these tests among our population was very limited.

While osteoporosis is not a disease that should be managed in an in-hospital setting, considering that fragility fractures are a direct consequence of osteoporosis, the request for these tests, in addition to a bone scan and a visit to the endocrinology or internal medicine service at the time of discharge, will help in making the diagnosis. It is also critical to involve the education programs and to assess the falls risk in each particular case, in order to lower the probability of experiencing new fractures in patients with osteoporosis.

In Colombia there are 13 hospitals participating in the above-mentioned program but only 3 score above 60% in terms of compliance with this campaign; 2 in Bogotá and one in Caldas.26 There are no hospitals participating in this program in Boyacá. It is essential to consider implementing these medical care standards in our institution, since our hospital is the referral center for Boyacá, and this may have a significant impact on our population.

Finally, further studies are needed for a better characterization of the population. Prospective trials may help in improving follow-up and the long-term assessment of patients undergoing early management. The «Capture the Fracture» strategy may provide a model for the implementation of an institutional secondary prevention program.

LimitationsThe sample size of our population is «small», but this study could be replicated with a larger sample size. An important limitation of this study is its retrospective nature, which depends on the information from the medical records; the lack of some data may change the prevalence of certain variables.

ConclusionThe behavior of fragility fractures in the population in our institution is similar to the behavior in other places, both at the national and international level, where the proportion of risk factors is also similar. It is therefore important to start creating awareness about secondary prevention in osteoporosis, in order to reduce the number of complications, improve outcomes and reduce the costs involved. Now, more than ever, the implementation of an institution-wide program is of the essence.

FinancingThe authors funded this study.

Conflict of interestsNone.

To the research committee and the staff of the archives of the Hospital Universitario San Rafael de Tunja (HUSRT).

Please cite this article as: Sankó Posada AA, González Castañeda AP, Vargas Rodríguez LJ, Gordillo Navas GC. Prevalencia de factores de riesgo en pacientes mayores de 50 años con fracturas clásicas de fragilidad atendidos en un hospital de tercer nivel de complejidad en Boyacá. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021;28:104–110.