Reactive arthritis (ReA) is a monoarthritis or oligoarthritis that mainly affects the extremities, it can be related to bacterial or viral infections. Currently, COVID-19 has been linked to the development of arthropathies due to its inflammatory component.

ObjectivesA scoping review of the literature that describes the clinical characteristics of ReA in survivors of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

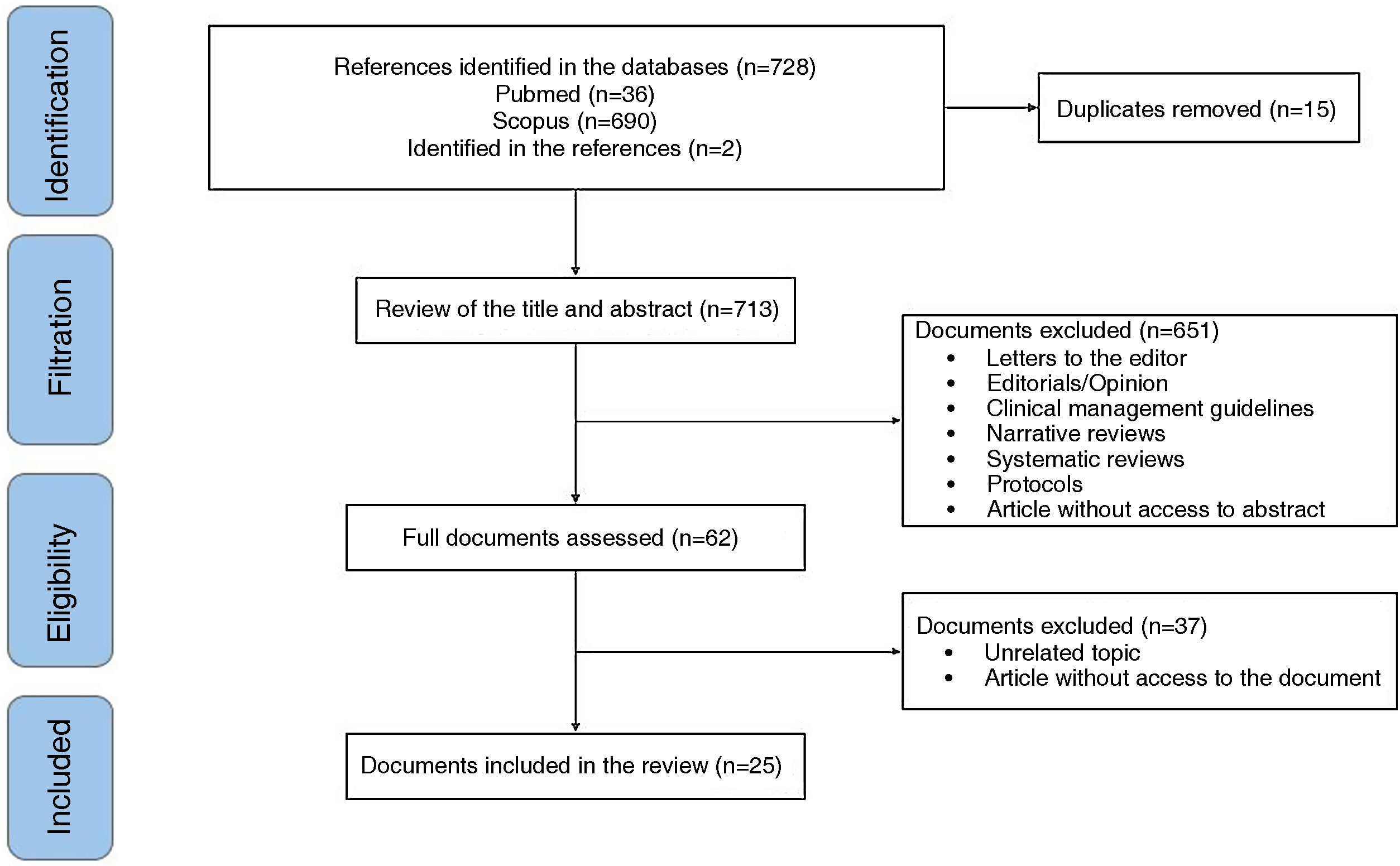

Materials and methodsA systematic review based on the guidelines for reporting systematic reviews adapted for Prisma-P exploratory reviews and steps proposed by Arksey and adjusted by Levan. Experimental and observational studies published in PubMed and Scopus, English and Spanish, which answered the research questions posed, were included.

ResultsTwenty-five documents were included describing the main clinical manifestations of ReA in 27 patients with a history of SARS-Cov-2 infection. The time from the onset of symptoms or microbiological diagnosis of COVID-19 to the development of articular and/or extra-articular manifestations compatible with ReA ranged from 7 days to 120 days. The clinical joint manifestations described were arthralgia and oedema, predominantly in knee, ankle, elbow, interphalangeal, metatarsophalangeal, and metacarpophalangeal joints.

ConclusionsArthralgias in the extremities are the main symptom of ReA in patients with a history of COVID-19, whose symptoms can present in a period of days to weeks from the onset of clinical symptoms or microbiological diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

La artritis reactiva (ReA) es una monoartritis u oligoartritis que compromete principalmente las extremidades, y se puede relacionar con infecciones bacterianas o virales. En la actualidad, la covid-19 se ha relacionado con el desarrollo de artropatías debido a su componente inflamatorio.

ObjetivosLlevar a cabo una revisión exploratoria de la literatura que describa las características clínicas de la ReA en pacientes sobrevivientes a la infección por SARS-CoV-2.

Materiales y métodosRevisión sistemática exploratoria basada en las guías para comunicar revisiones sistemáticas adaptadas para las revisiones exploratorias Prisma-P y pasos propuestos Arksey y ajustados por Levan. Se incluyeron estudios de tipo experimental y observacional publicados en PubMed y Scopus, en inglés y español, que respondieran las preguntas de investigación planteadas.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 25 documentos que describen las principales manifestaciones clínicas de la ReA en 27 pacientes con antecedente de infección por SARS-Cov-2. El tiempo desde el inicio de los síntomas o diagnóstico microbiológico de la covid-19 hasta el desarrollo de manifestaciones articulares o extraarticulares compatibles con ReA osciló entre 7 y 120 días. Las manifestaciones articulares clínicas descritas fueron las artralgias y el edema de predominio en articulaciones de las rodillas, tobillos, codos, interfalángicas, metatarsofalángica y metacarpofalángica.

ConclusionesLas artralgias en las extremidades son el principal síntoma de la ReA en pacientes con antecedente de covid-19. Sus síntomas se pueden presentar en un periodo de días a semanas, desde el inicio de los síntomas clínicos o el diagnóstico microbiológico de la infección por SARS-CoV-2.

Infection by the new coronavirus type 2, which causes the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2), is responsible for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.1,2 The pathophysiological mechanisms of COVID-19 are related to immune-mediated processes and tissue damage that generate from mild symptoms to severe cases of the disease, due to complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome or multiple organ failure, among others.2,3 SARS-CoV-2 infection can trigger a wide number of physical or mental sequelae (dyspnea, fatigue, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, anxiety), whose onset time varies from days to weeks after diagnosis, and last even for more than 12 weeks.4,5 Osteomuscular symptoms in patients who survive COVID-19 are a topic of medical interest, due to the increasing number of cases and the absence of criteria or clinical practice guidelines that facilitate a diagnostic and therapeutic approach.4,6

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) are a group of diseases that compromise the axial skeleton (sacroiliitis) or the peripheral skeleton (arthritis, tenosynovitis and enthesitis).7–9 Reactive arthritis (ReA) is a type of SpA that can present as monoarthritis or oligoarthritis (mainly in the extremities), positive for HLA-B27 in 50 to 70% of cases, enthesitis, dactylitis and extra-articular manifestations (urethritis, psoriasis and conjunctivitis).6,8,9 ReA can be related to bacterial (Chlamydia psittaci, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae) or viral infections.8,9 Currently, SARS-CoV-2 infection is an important trigger of this rheumatological disease.10

The pathophysiological processes of ReA in surviving patients could be related to COVID-19 due to the overactivation of the innate immune system and a molecular mimicry generated by the epitopes present at the tissue level,11 whose osteomuscular clinical manifestations are similar to those described before the current pandemic.5,12,13 However, there is no complete clarity regarding the main characteristics and temporality of the symptoms.14–16 The objective of the manuscript is to perform an exploratory review of the literature that describes the clinical characteristics of ReA in patients who survived the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

MethodsExploratory systematic review based on the steps proposed by Arksey17 and adjusted by Levan18: 1) define the research question; 2) search for relevant studies; 3) selection of studies; 4) data extraction, and 5) summarize the report of the results. The review adhered to the aspects recommended in the guidelines for reporting systematic reviews adapted for Prisma-P scoping reviews.19 (Supplementary material 1).

The research questions were: how can the available medical evidence about the relationship between ReA secondary to COVID-19 be described? and, how can be described the main osteomuscular clinical manifestations in patients with ReA who survive COVID-19?

The PICOT question is described to identify in the literature patients diagnosed with ReA during or after SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a diagnosis by polymerase chain reaction, ELISA test or high clinical suspicion. This, in order to describe the course of the disease and identify differences between ReA patients with COVID-19 (Supplementary material 2).

Eligibility criteriaThis review includes experimental and observational studies published in English and Spanish that answered the research question posed. For all potentially eligible publications, authors must have access to titles, abstracts, and full documents. Theoretical publications such as literature reviews, systematic reviews, position articles, clinical management guidelines, and letters to the editor are excluded. In addition, articles about patients with osteomuscular symptoms related to vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infection were not taken into account.

Information sources and search strategyPubMed and Scopus were used as databases, while the search strategies were structured with Boolean operators, and the appropriate keywords of each platform were guided by a librarian (Supplementary material 3). The documents obtained as a result of the search strategies were evaluated by 3 of the authors (ETQ, JO, JCG). References cited in the included papers, if they met the inclusion criteria and had not been previously identified, were also included in the exploratory review.

Data extraction and synthesisThe review of the titles and abstracts of the publications found in the databases was carried out by the authors (ETQ, JO, JCG), according to the eligibility criteria in the Rayyan free access web application for the management of systematic reviews.20 For the publications in which there was some doubt about their inclusion, the remaining authors met to decide their usefulness in the review. The articles included were reviewed in full text by all authors, and the following information was extracted: authors, characteristics of the population, objective, duration of the onset of symptoms since the clinical or microbiological diagnosis of the infection, and main clinical manifestations. Regular meetings were held to discuss and adjust these synthesis formats.

The results are presented following the categories proposed by Grudniewicz et al.21: a) a summary of the characteristics and distribution of the publications included, and b) a narrative synthesis of the results.

ResultsOf 148 documents identified by the search, 25 that describe the main clinical manifestations of ReA related to COVID-19 were included (Fig. 1).

In all the included documents, 27 patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection are described. The time elapsed between the onset of symptoms related to the active infection or the microbiological diagnosis of COVID-19 and the development of articular or extra-articular manifestations compatible with ReA generally ranges between 7 and 120 days. The clinical joint manifestations described were arthralgias and edema predominantly in the knees, ankles, elbows, interphalangeal, metatarsophalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints. The general characteristics of the publications included are described in Table 1.

Characteristics of the publications included.

| Authors | Characteristics of the population | Objective | Temporality of the onset of symptoms (days)a | Main finding/contribution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quaytman et al.22 | A 42-year-old man with a history of lung adenocarcinoma in remission | Description of a case of ReA and silent thyroiditis after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 21 | Patient with asymmetric oligoarthritis predominantly in the knee and imaging findings compatible with enthesitis. There was improvement in symptoms with the administration of glucocorticoids |

| Ouedraogo et al.13 | A 45-year-old man with a history of chronic low back pain | Presentation of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection with severe symptoms | 48 | Patient with pain and edema in the left knee joint. There was improvement in symptoms with the administration of glucocorticoids |

| Shimoyama et al.23 | A 37-year-old man with a history of right ankle fracture and hyperuricemia | Presentation of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 31 | Patient with asymmetric oligoarthritis predominantly in the right ankle. Total improvement of symptoms after arthroscopic synovectomy of the right ankle, performed after failure of medical treatment |

| Ono et al.24 | A 50-year-old man with a history of steatohepatitis | Presentation of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 21 | Patient with secondary bilateral arthritis in the ankles. Partial improvement of symptoms with intra-articular application of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| Kocyigit and Akyol25 | A 53-year-old woman with a history of arterial hypertension | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 41 | Patient with pain and edema in the left knee joint, morning stiffness and limitation of joint movement |

| Saricaoglu et al.26 | A 73-year-old man with a history of diabetes, arterial hypertension, and coronary heart disease | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 14 | Patient who presented oligoarthritis in the left proximal and distal metatarsophalangeal and interphalangeal joints. There was improvement of symptoms with the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Schenker et al.27 | A 65-year-old woman with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA and cutaneous vasculitis after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 10 | Patient with polyarthritis predominantly in the ankles, knees and metacarpophalangeal joints. On the other hand, clinical characteristics compatible with cutaneous vasculitis |

| Kuschner et al.28 | A 73-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension | Report of a case of ReA after the SARS-CoV-2 infection | 16 | Patient with monoarthritis in the right metacarpophalangeal joint |

| Dutta et al.29 | A 14-year-old male patient with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 21 | Patient with polyarthritis in the right elbow, knee and ankle. Received treatment with glucocorticoids |

| Hønge et al.30 | A 53-year-old man with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 16 | Patient with polyarthralgias in the right knee and ankle and in the left metatarsophalangeal joints |

| Liew et al.31 | A 47-year-old man with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 7 | Patient with right gonalgia and balanitis. There was improvement in symptoms with the administration of glucocorticoids |

| Coath et al.32 | A 53-year-old man with a history of lumbar disc herniation | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | Not described | Patient with cervical and dorsal pain at the thoracic and lumbar levels. Diagnostic images with evidence of edema in the sacroiliac and costovertebral joints |

| Jali33 | A 39-year-old woman with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 21 | Patient with pain in the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints of both hands. There was improvement of symptoms with the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Fragata and Mourão34 | A 41-year-old woman with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 30 | Patient with pain and edema in the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints of both hands. Partial improvement of the symptoms with the administration of glucocorticoids |

| De Stefano et al.35 | A 30-year-old man with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 10 | Patient with elbow monoarthritis and psoriasis. Improvement of symptoms with the administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and topical glucocorticoids |

| Danssaert et al.36 | A 37-year-old woman with a history of heart failure, asthma, and morbid obesity | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 12 | Patient with monoarthritis in the right metacarpophalangeal joint. Improvement of symptoms with the administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids |

| Gasparotto et al.37 | A 60-year-old woman with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 32 | Patient with oligoarthritis of the right ankle and knee. There was improvement of symptoms with the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Parisi et al.38 | A 58-year-old woman with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 25 | Patient with monoarthritis of the ankle. Partial improvement of symptoms with the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Yokogawa et al.39 | A 57-year-old man with a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 15 | Patient with oligoarthritis of the shoulder, knee and metacarpophalangeal joint |

| López-González et al.40 | Four men, 3 of whom had a history of gouty arthritis | Report of cases of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 8, 19, 8 and 27 | Patients with monoarthritis and oligoarthritis of the knee, ankle and metacarpophalangeal joint |

| Di Carlo et al.41 | A 55-year-old man with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 37 | Patient with monoarthritis of the right ankle. There was improvement in symptoms with the administration of glucocorticoids |

| Sureja and Nandamuri42 | A 27-year-old woman with no significant antecedents | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 14 | Patient with oligoarthritis of the knee, ankle and metacarpophalangeal joint. Partial improvement of symptoms with the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Santacruz et al.43 | A 30-year-old woman with a history of COVID-19 4 months before | Report of a case of ReA with extra-articular manifestations after SARS-CoV-2 infection | 120 | Patient without joint involvement. Painful ulcers on the labia majora, skin lesions with psoriasiform characteristics on the soles of the feet, subungual hyperkeratosis and dactylitis of the fourth toe of the left foot are documented |

| Santacruz et al.44 | A 30-year-old male patient with a history of COVID-19 one month before | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 and HIV infection | 30 | Patient with additive and symmetrical polyarticular pain, located in the wrists, knees and left shoulder. There was improvement in symptoms with the administration of glucocorticoids |

| Ruiz-del-Valle et al.45 | A 19-year-old male patient with a history of alopecia areata and pityriasis versicolor | Report of a case of ReA after SARS-CoV-2 infection | Not described | Patient with symmetrical polyarthritis in the metacarpophalangeal joint, elbow and right ankle. There was improvement in symptoms with the administration of glucocorticoids |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; ReA: reactive arthritis; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

Ouedraogo et al.13 reported the case of a 45-year-old male patient with a history of arterial hypertension, prostate cancer and chronic low back pain, who was hospitalized for 45 days due to COVID-19, requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and renal replacement therapy. It was described that 7 days after hospital discharge, the patient was readmitted due to severe pain, erythema and edema in the left knee, associated with fever and tachycardia. Despite having elevated inflammatory markers, the left knee arthrocentesis showed no evidence of crystals or microorganisms in the synovial fluid compatible with septic arthritis, while antigenic and serological tests against the most common pathogens were negative.

Shimoyama et al.23 reported the case of a 37-year-old man with a history of right ankle fracture and hyperuricemia, who 6 days after the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection developed pain in the right ankle, without improvement after the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The synovial fluid aspirate revealed inflammatory cells, while the MRI of the affected joint revealed synovitis without cartilage wear. The patient underwent arthroscopic synovectomy, finding bone damage in the medial malleolus; and days after the surgical intervention, resolution of clinical symptoms was observed. Due to the relationship with the recent diagnosis of COVID-19, it was considered the first report of ReA with bone erosion after the viral infection.

Kuschner et al.28 presented the case of a 73-year-old man with a history of systemic arterial hypertension and chronic intermittent pain in the right metacarpophalangeal joint, who consulted due to worsening of the joint pain, associated with diarrheal stools without mucus or blood, dry cough and fever of 15 days of evolution. Pain treatment was started with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and it was decided to perform diagnostic arthrocentesis to rule out septic arthritis, whose synovial fluid was cloudy, without crystals, Gram stain without microorganisms and negative cultures at 48 h. Likewise, it was decided to perform reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction for COVID-19 of the synovial fluid and an antigen test for COVID-19, which were positive. The authors concluded that this was the first case that demonstrated the presence of disseminated COVID-19 in a joint and its possible correlation as a trigger of ReA.

Santacruz et al.43 described the clinical case of a 30-year-old woman with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection 4 months earlier, without requiring ventilatory support, who consulted with a clinical picture of odynophagia associated with anosmia, dysgeusia, bilateral conjunctival injection, fever and dyspnea of 6 days of evolution. Painful ulcers on the labia majora, skin lesions with psoriasiform characteristics on the soles of the feet, subungual hyperkeratosis, and dactylitis of the fourth toe of the left foot were documented during the physical examination. The patient presented a report of an antigen test positive for COVID-19, and received treatment according to the Recovery protocol, without progression of the disease to lung involvement, for which she was discharged from the hospital.

Santacruz et al.44 described the clinical case of a 27-year-old man who was admitted with a clinical picture of 5 days of evolution consisting of additive, symmetrical polyarticular pain, located in the metacarpophalangeal joints, the knees and the left shoulder, which caused limitation of the movement. The patient reported SARS-CoV-2 infection, confirmed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction one month before the onset of symptoms. The findings described in the MRI showed bursitis of the lateral collateral ligament of the left lower limb and a peritendinous inflammatory process of the triangular fibrocartilage in the right wrist. Among the differential diagnoses, a fourth-generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the detection of the human immunodeficiency virus was performed, which was positive with a subsequent CD4 count of 98 cells/mm3 and a viral load of 459,000 copies/mL. Treatment with prednisolone and sulfasalazine was started, without significant improvement in joint symptoms, and, simultaneously, antiretroviral therapy (abacavir, dolutegravir/lamivudine) achieved gradual improvement in symptoms.

DiscussionWithin the clinical characteristics of ReA in patients who survive COVID-19, pain and edema in the joints of the extremities, including the knee and the ankle, after a period of days to weeks from the onset of clinical symptoms or the microbiological diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection are mainly described13,22–45; extra-articular manifestations without joint involvement are infrequent in patients with a history of COVID-19.35,43 Treatments with glucocorticoids with significant improvement in associated symptoms are described in a high percentage of patients22,23,29,31,34,41,44,45; and to a lesser extent, pharmacological treatment with non-glucocorticoid anti-inflammatory drugs was used.13,24,26,32,35–37,40

The articular clinical manifestations in ReA are erythema, edema and inflammatory pain, which may or may not occur together with extra-articular symptoms,23,38,39 with oligoarticular and monoarticular involvement being the most frequent forms of presentation of the disease.46–48 Despite the fact that there is variety and poor performance in the criteria established for the diagnosis of ReA associated with COVID-19, it is proposed to use the term of clinical pictures with osteomuscular symptoms and signs related to the viral infection and laboratory tests.6–8,43,46 The most frequent extra-articular manifestations in patients with ReA are urethritis, cervicitis, salpingo-oophoritis, cystitis, prostatitis, conjunctivitis, and aphthous ulcers, among others.48 Even though the described cases of ReA after COVID-19 are mostly characterized by arthritis and dactylitis, 2 cases with involvement at the cutaneous and genitourinary levels are reported in this exploratory review.35,43

The diagnosis of ReA related to COVID-19 is limited, due to the variety of musculoskeletal symptoms present in the convalescence period or post-COVID syndrome, the poor performance of the current classification criteria and the history of rheumatological diseases with joint involvement.49,50 On the other hand, the use of medications such as corticosteroids or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during moderate or severe active infection could potentially reduce the occurrence of musculoskeletal symptoms and extra-articular manifestations.7,8,23,35,45 Given the high number of patients who survive SARS-CoV-2 infection, studies are needed that allow us to understand the pathogenesis of COVID-19 in the different clinical phenotypes of joint involvement, the incidence and evolution of inflammatory manifestations, with a favorable impact on the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of the disease.46,50

The treatment of ReA aims to reduce clinical symptoms and the articular and extra-articular inflammatory process; non-glucocorticoid anti-inflammatory drugs are the first line, while systemic glucocorticoids are an option in refractory disease.5,6,13,22 A surgical treatment such as synovectomy, used in patients who do not respond to pharmacological treatment, is useful to improve pain and prevent bone erosion in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or Reiter's syndrome, because the hypertrophic synovial membrane with infectious agents is removed23,48,49; however, the impact that this procedure may have on patients with ReA is unknown.50 Treatment for extra-articular manifestations has been indicated only focused on the control of symptoms, or with topical glucocorticoids, due to the low evidence available and the fact that in most cases they are self-limiting.43,50

The immune system in patients with ReA is characterized by molecular mimicry events, as a consequence of the high load of microorganism antigens, which generates an autoimmune cross-reaction with specific human proteins and an inflammatory response by B cells, CD4+ T cells and interleukins at the intraarticular level.5,7,13 Patients with COVID-19 present an inflammatory response with a marked elevation of Th17 cells, tumor necrosis factor, interferon-γ and interleukin-17, the latter related to the pathophysiology of ReA.43,51 Even though the development of ReA in patients diagnosed with COVID-19 is related to a process of inflammatory response and tissue injury triggered by exposure to the virus, the development of this arthropathy can occur in mild, moderate and severe cases of the disease.13,22–45

The presentation and musculoskeletal sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 are mainly related to a post-infectious multisystem inflammatory syndrome and inflammatory reactions after the virus has been eliminated.5,9,13,45,52 The clinical symptoms described in post-COVID syndrome were also observed in previous infectious diseases, such as Middle East respiratory syndrome and severe acute respiratory syndrome, due to the extensive tissue damage in organs and systems.4,5,53,54 The joint pain can usually last from 6 weeks to 3–6 months after the SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the duration may be related to the anti-inflammatory medical treatment established and the severity of the disease.6,48

The viral agents with capacity to cause joint damage most frequently are, in general, parvovirus, alphavirus, hepatitis B, hepatitis C virus, Epstein-Barr, Zika, and chikungunya, which trigger symptoms such as fever, rash, and lymphadenopathy.52,53,55,56 The diagnostic definition of ostseomuscular symptoms related to ReA in patients who survive COVID-19 is similar to viral-mediated arthritis, which is characterized by being self-limiting, as well as by the presence of synovial fluid positive for the infectious agent and patients who respond to treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. However, it is necessary to establish criteria and definitions for a timely clinical diagnosis of these 2 diseases with a high incidence today.4,13,53,54

LimitationsIn the vast majority of the studies included in this review, there was a lack in the definition of the osteomuscular symptoms characteristic of ReA, as well as their differences with other rheumatological or infectious diseases that affect the joints.21,43,45 On the other hand, all of the included studies were purely descriptive observational studies, without taking into account the age and other variables that worsened symptoms, such as sleeping habits, employment and physical activity.

The evidence was extracted only from PubMed and Scopus, in Spanish and English; nevertheless, the members of the research team are experienced in properly extracting and synthesizing this type of data. Being an exploratory review, the quality of the evidence was not evaluated, in accordance with the recommendations made by the Prisma-ScR guideline.17–19

ConclusionThe medical literature describes pain in the joints of the extremities as one of the main clinical manifestations of ReA in patients with a history of COVID-19, whose symptoms can occur within a period of days to weeks, from the onset of the clinical symptoms or the microbiological diagnosis of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, for a timely diagnosis and therapeutic approach, it is necessary to establish criteria and definitions of ReA in patients who survived COVID-19.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.