To describe the safety and response to treatment with RTX, estimating its impact on the health state utility (HSU) of patients with refractory lupus nephritis (LN) treated in referral centres in several cities in Colombia.

MethodsA registry-based follow-up study. Patients aged between 16 and 75 years, who were refractory to first-line management and had ISN / RPS class III-IV (+/- V) LN, were included. Our primary outcome was total or partial response to treatment; secondary outcomes were HSU measured with the EQ-5D-3 L, and safety of treatment with RTX. The impact analysis of response to RTX on HSU were performed by mean difference estimated by robust regression.

ResultsForty-six patients (44 women) were included, with a median age of 34 years (IQR = 13), the median SDI was 1 (IQR = 1) and the median activity measured by SLEDAI was 4.5 (IQR = 5.9). Response to RTX was observed in 27 (58.7%) patients. Adjusted for SLEDAI and co-interventions, the patients who responded to RTX obtained a higher mean HSU by 0.162 (95% CI 0.006–0.317). Which is equivalent to 1.9 (95% CI 0.2–3.8) more months lived in ideal health conditions for each year with refractory LN. In 54.3% of the patients, RTX had adequate safety.

ConclusionFrom the patient's perspective, the response to treatment with RTX in patients with refractory LN implies a significant impact on their quality of life.

Describir la seguridad y la respuesta al tratamiento con RTX, estimando su impacto en la utilidad del estado de salud de pacientes con nefritis lúpica (NL) refractaria tratados en un centro de referencia de varias ciudades de Colombia.

MétodosEstudio de seguimiento a una cohorte basado en registros. Se incluyeron pacientes con edades entre 16 y 75 años, a quien se les documentó NL clase III-IV (+/− V) según criterios de la International Society of Nephrology/Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS), refractarios al manejo de primera línea. Como desenlace principal se definió la respuesta total o parcial al tratamiento, y como desenlaces secundarios, la utilidad del estado de salud (UES) medida mediante el EQ-5D-3 y la seguridad al tratamiento con RTX. Los análisis de impacto en la UES se realizaron mediante diferencias de medias según respuesta de tratamiento con regresión robusta.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 46 pacientes (44 mujeres), con una edad mediana de 34 años (RIC = 13), mediana de SDI de 1 (RIC = 1) y mediana de actividad por SLEDAI de 4,5 (RIC = 5,9). Se observó respuesta al RTX en 27 (58,7%) pacientes. Con ajuste por SLEDAI y cointervenciones, los pacientes que respondieron al RTX obtuvieron una media de UES mayor en 0,162 (IC 95% 0,006−0,317), lo cual equivale a 1,9 (IC 95% 0,2–3,8) meses más del tiempo vivido en condiciones de salud ideal por cada año con NL refractaria. El 54,3% de los pacientes tuvo una adecuada seguridad al RTX.

ConclusiónDesde la perspectiva del paciente, la respuesta a tratamiento con RTX en pacientes con NL refractaria implica un impacto relevante en su calidad de vida.

Renal involvement in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) usually occurs during the first 3 years of the disease and can be found in up to 90% of renal biopsies; half of these cases entails clinically significant disease.1–3 The prevalence of this manifestation depends on ethnicity, with a prevalence of lupus nephritis (LN) of 27.9% in the EuroLupus cohort and 51.7% in GLADEL (Multinational Latin American Lupus Cohort).4,5

The treatment of LN is determined by the classification system proposed by the International Society of Nephrology and the Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS). Systemic steroids in combination with cyclophosphamide (CYC) or mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) are the first-line therapy for the induction of remission.4,5 Approximately 20–30% of patients will have a disease refractory to these treatments, and 50% will relapse, despite maintenance therapy.6 Refractoriness is defined as persistence of proteinuria >500−700 mg/day at 6−12 months, active sediment and worsening renal function.7

Due to the higher mortality and damage accumulation among the patients with refractory lupus nephritis (RLN),8 other treatment options become relevant. Although rituximab (RTX) did not achieve the primary outcomes in the two randomized clinical trials designed to evaluate its efficacy in renal and non-renal manifestations of SLE (LUNAR9 and EXPLORER7 studies), it has shown a good safety and efficacy profile for the treatment of refractory manifestations in SLE, particularly in arthritis and LN in cohort and open studies.4,5,10,11 Due to its cost, the disparity of evidence and the lack of knowledge of its true impact on quality of life, specifically in patients with LN,12,13 the generation of evidence on the results obtained in real conditions of clinical practice becomes relevant.

The objective of this study was to describe the safety and response to treatment with RTX, estimating its impact on the health state utility (HSU) of patients with RLN treated in a referral center in several cities in Colombia.

MethodsStudy designA descriptive follow-up study of a registry-based cohort was conducted. Approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the CES University was obtained, and the confidentiality and integrity of patients data was respected. This report follows the recommendations of the STROBE statement.14

Context and participantsPatients aged between 16 and 75 years, who had class III-IV (± V) LN documented according to ISN/RPS criteria, refractory to first-line management with steroids in combination with CYC or MMF were included. Refractoriness was defined as the persistence of proteinuria >0.5 g/day at 12 months.15,16 Patients who had already received treatment with RTX or other anti-CD20 therapy, who had had infections prior to the application of RTX, clinically relevant solid or hematological malignancy, and allergies or any contraindication to receiving the medication were excluded.

The patients included are part of the program of surveillance and monitoring of autoimmune diseases of an institution specialized in risk management in high-impact diseases with centers in Armenia, Bogotá, Cali, Manizales, Medellín, Montería, Pasto, Pereira and Tunja. Data were taken from the clinical history of patients registered between January 2015 and May 2020.

VariablesThe primary outcome was defined as the total or partial response to treatment, assessed qualitatively according to the report of the results documented in the clinical history. The response was defined then as a reduction in proteinuria by 50% at 6 months or a proteinuria < 700 mg at 12 months.17 The HSU measured using the EQ-5D-3 and the safety of treatment with RTX were taken as secondary outcomes.

The cumulative dose and the qualitative response to each medication were considered as variables of the pharmacological management. The clinical variables that were taken into account were age at onset of LN, age at onset of RLN, quantitative cumulative damage index (SDI), Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI), antinuclear antibodies (ANA) with their respective titers and pattern, and the data from the urinalysis and renal biopsy with the respective classification of LN. Other clinical variables included the development of end-stage renal disease, the need for dialysis, and kidney transplantation. In addition, the sociodemographic variables sex, age, education, stratum and area of residence were included.

Sample size and bias controlFrom the patients with SLE registered in the database, all patients with LN and those refractory to initial management were obtained, and finally the refractory patients who received RTX were analyzed. To control possible biases, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were thoroughly reviewed, and when patients were included, the clinical histories were verified by trained and standardized personnel. Standardization was carried out during the pilot test and the quality of the data was verified by external audit. Furthermore, for confounding by indication, the epidemiological measures of risk and mean differences were adjusted by baseline prognostic characteristics of the patients using multiple regression. A second review of the clinical history was carried out for the missing data, making emphasis on them. Data that could not be documented are reported.

Statistical analysisThe descriptive analysis was carried out using frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables and with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for quantitative variables. The mean ages at the onset of LN and RLN were estimated using Log-normal regression for interval censored data: patients with unknown age at onset were left-censored, while patients who presented with LN or RLN during the follow-up period were interval-censored. Mean estimates are presented along with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

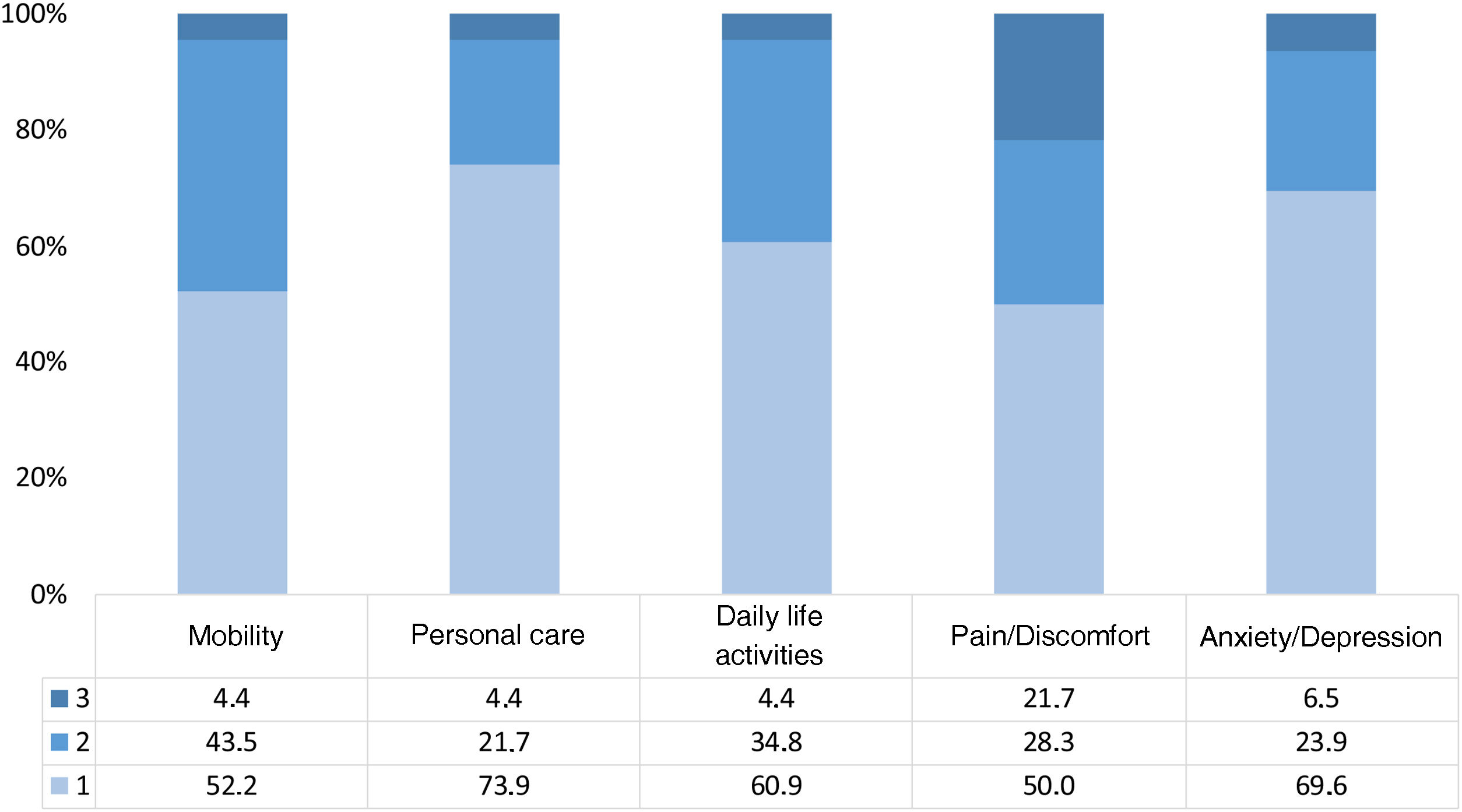

The safety and the response to RTX are presented using frequencies and percentages. The HSU is presented by mean (SD) and median (IQR). The impact profile by dimension of the EQ-5D-3 L is presented graphically.

The impact of the response to treatment on the HSU was analyzed by the difference of means observed and adjusted for SLEDAI, sex, cumulative dose of RTX and use of CYC, MMF and methylprednisolone. These differences were estimated using a robust regression, because the measure of HSU does not fit the assumption of normality. Sensitivity analysis was performed estimating differences in medians, observed and adjusted using quantile regression. Estimates are presented along with the 95% CI and p-values. The significance level was set at 0.05 and differences in HSU ≥0.07 were considered clinically relevant according to the minimal clinically important difference threshold report in patients with SLE.18 The analyses were run in Stata version 16.1 (College Station, TX, USA).

ResultsParticipantsOf 1209 patients with a diagnosis of SLE, 276 had LN. Of them, 46 were refractory and received RTX. These 46 were followed-up for one year and analyzed.

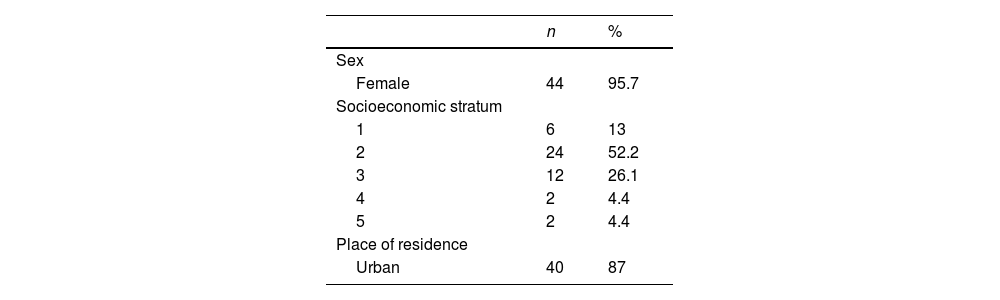

Characteristics of the participantsOf the 46 patients analyzed during the 12 months (Table 1), 44 (95.65%) were women; the median age was 34 years (IQR = 13) and the median number of years of education was 11 years (IQR = 2); 6 (13.04%) patients corresponded to socioeconomic stratum 1, while 24 (52.17%) belonged to stratum 2; 40 (86.96%) of them were residents of urban areas. In addition, the median SDI was 1 (IQR = 1) and the median activity by SLEDAI was 4.5 (IQR = 5.9). The average age at diagnosis of LN was 25.6 years (95% CI: 23.0–28.1), and for RLN it was 30.5 years (95% CI: 27.7–33.3). The median duration of LN was 14 years (IQR = 4.9).

Since the diagnosis of LN, 43 patients in the cohort used CYC or MMF. 74% started with CYC, the rest with MMF, and once the failure of this therapy was demonstrated, the treatment was changed to MMF or CYC, respectively. Of the patients who at some point presented a response to CYC or MMF, this response was maintained on average for months.

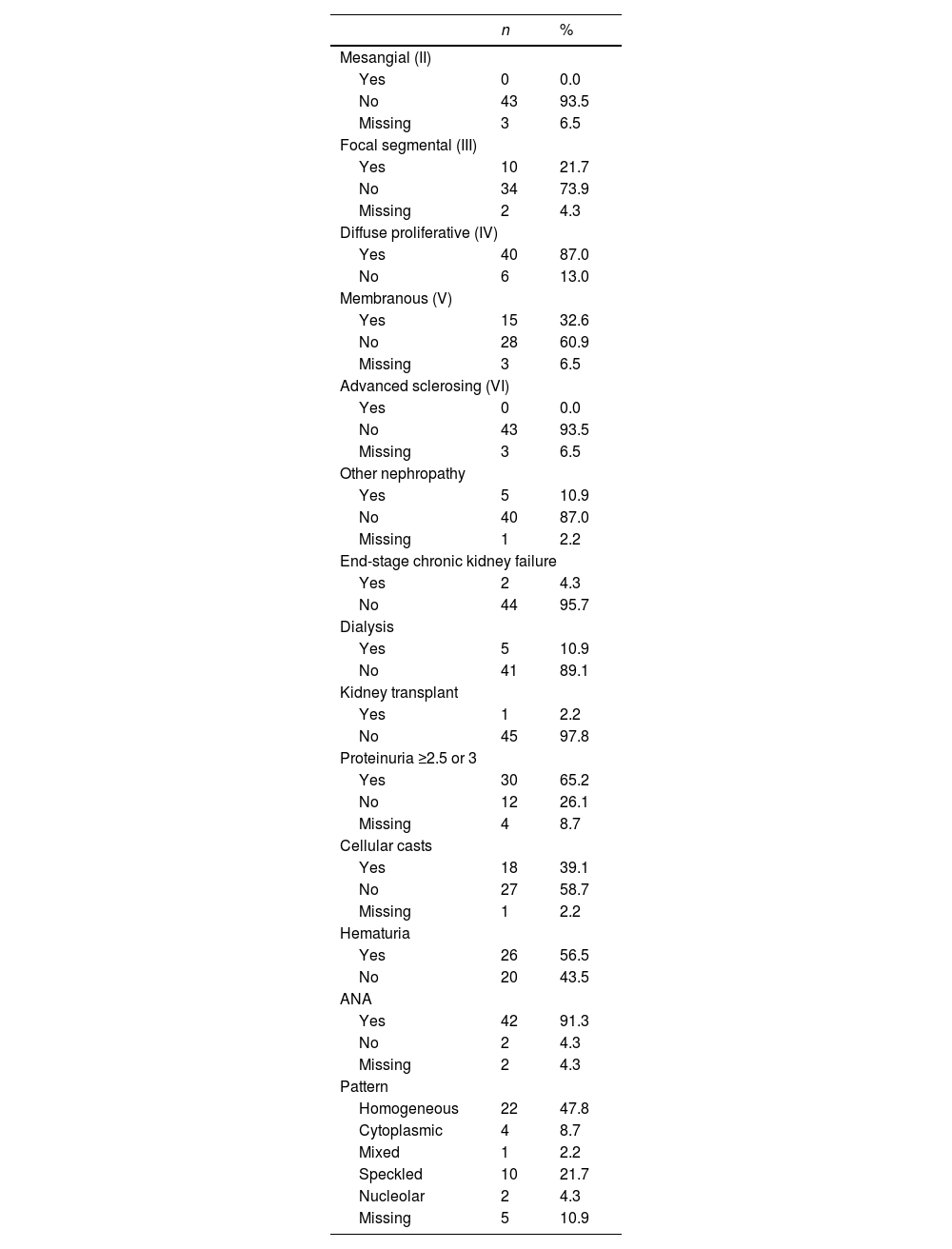

As for the histological and renal characteristics (Table 2), 10 (21.7%) patients had an ISN/RPS classification class III, 40 (87%) class IV and 15 (32.6%) class V, without being exclusive of each other. In total, 5 (10.9%) patients required dialysis at some point during follow-up, 2 progressed to chronic kidney disease and one was taken to kidney transplant (Table 3).

Histological and renal characteristics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Mesangial (II) | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 |

| No | 43 | 93.5 |

| Missing | 3 | 6.5 |

| Focal segmental (III) | ||

| Yes | 10 | 21.7 |

| No | 34 | 73.9 |

| Missing | 2 | 4.3 |

| Diffuse proliferative (IV) | ||

| Yes | 40 | 87.0 |

| No | 6 | 13.0 |

| Membranous (V) | ||

| Yes | 15 | 32.6 |

| No | 28 | 60.9 |

| Missing | 3 | 6.5 |

| Advanced sclerosing (VI) | ||

| Yes | 0 | 0.0 |

| No | 43 | 93.5 |

| Missing | 3 | 6.5 |

| Other nephropathy | ||

| Yes | 5 | 10.9 |

| No | 40 | 87.0 |

| Missing | 1 | 2.2 |

| End-stage chronic kidney failure | ||

| Yes | 2 | 4.3 |

| No | 44 | 95.7 |

| Dialysis | ||

| Yes | 5 | 10.9 |

| No | 41 | 89.1 |

| Kidney transplant | ||

| Yes | 1 | 2.2 |

| No | 45 | 97.8 |

| Proteinuria ≥2.5 or 3 | ||

| Yes | 30 | 65.2 |

| No | 12 | 26.1 |

| Missing | 4 | 8.7 |

| Cellular casts | ||

| Yes | 18 | 39.1 |

| No | 27 | 58.7 |

| Missing | 1 | 2.2 |

| Hematuria | ||

| Yes | 26 | 56.5 |

| No | 20 | 43.5 |

| ANA | ||

| Yes | 42 | 91.3 |

| No | 2 | 4.3 |

| Missing | 2 | 4.3 |

| Pattern | ||

| Homogeneous | 22 | 47.8 |

| Cytoplasmic | 4 | 8.7 |

| Mixed | 1 | 2.2 |

| Speckled | 10 | 21.7 |

| Nucleolar | 2 | 4.3 |

| Missing | 5 | 10.9 |

Own elaboration.

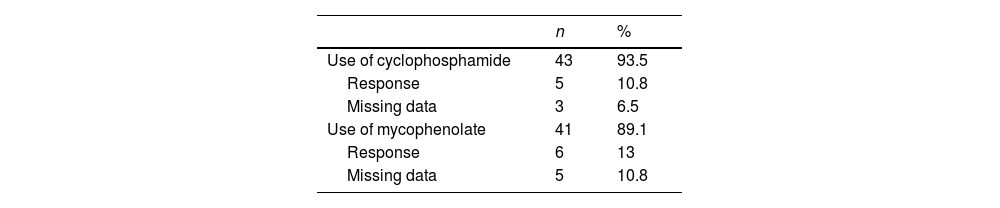

Regarding baseline clinical variables, it should be noted that 30 (65.2%) patients had proteinuria above 2.5 g in 24 h, 26 (56.5%) presented hematuria and in 18 (39.1%) cases cellular casts were observed in the urinalysis. ANAs were positive in 42 (91.3%) cases, being the homogeneous pattern the most commonly reported, which corresponded to 57.8% of the cohort. 93.5% of the patients were treated with CYC in a high-dose monthly scheme (0.5−1 g/m2 monthly), with a response rate of 10.8% and a cumulative dose of 6.5 g. Likewise, 89.1% of patients received MMF, with a response of 13% (Table 2).

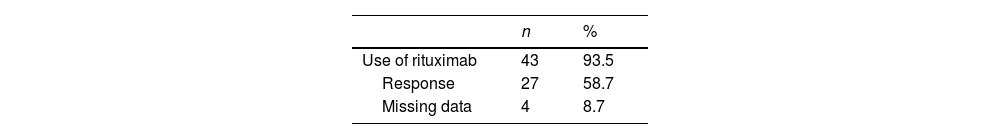

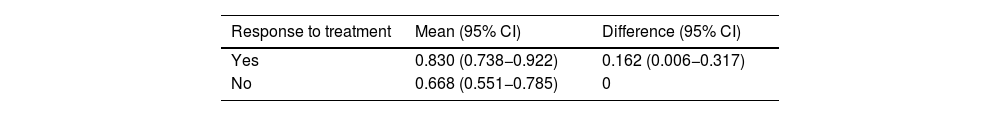

Response to treatment, safety and health state utilityA response to treatment with RTX was observed in 27 (58.7%) patients (Table 4), whose mean HSU was 0.830 (95% CI: 0.738−0.922); among those who did not show response to treatment, the mean HSU was 0.668 (95% CI: 0.551−0.785). With adjustment for SLEDAI and co-interventions, the patients who responded to treatment with RTX obtained a mean HSU higher in 0.162 (95% CI: 0.006−0.317). The difference between medians of HSU was 0.208 (95% CI: 0.017−0.399). This difference implies that for every year lived with RLN, the responders to RTX lose the equivalent of between 1.9 (95% CI: 0.2–3.8) and 2.5 (95% CI: 0.2–4.8) less months of time lived in ideal health conditions, compared with the patients who did not respond to treatment (Table 5). 54.3% of the patients have an adequate safety with the treatment with RTX. The collected data of the adverse events were poorly reported. The most frequently reported was anaphylaxis. There were no major adverse events that led to discontinuation of the drug. In 3 of the patients, the application of the first dose of RTX was delayed due to administrative problems with their insurance company.

Difference in health state utility between responders and non-responders to treatment with rituximab.

| Response to treatment | Mean (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 0.830 (0.738−0.922) | 0.162 (0.006−0.317) |

| No | 0.668 (0.551−0.785) | 0 |

| Response to treatment | Median (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 0.819 (0.710−0.928) | 0.208 (0.017−0.399) |

| No | 0.611 (0.466−0.756) | 0 |

| Adjusted for SLEDAI and use of co-interventions (cyclophosphamide and mycophenolate). | ||

Own elaboration.

In Colombia, it is estimated that half of the adults with SLE will present kidney involvement at some point in their lives, with a predominance of severe histological forms that are characterized by low remission rates15,16,19–21and progression to end-stage chronic kidney disease in one out of every 4–10 patients.22,23

The use of RTX in SLE and LN has generated controversy due to the results of the randomized clinical trials EXPLORER7 and LUNAR,9 as no additional benefit to standard therapy was found; however, several real-life reports have suggested an important role in RLN,9,24 while the difficulties in the evaluation of outcomes with the clinimetrics used in these studies have led to their widespread off-label use.9,10,15,16,19–30 In a cohort of 164 patients with LN who received RTX, half of whom were refractory, complete renal response has been described in 30% of cases at 12 months, with a lower response rate in those with class IV LN.25 Another study, with a Korean population, analyzed 39 patients with refractory SLE, of whom 17 had LN, and a partial renal response was reached in 11 of the 17, without achieving a complete renal response.26 Finally, in a subgroup of 32 Colombian patients with RLN, 61.53% obtained a renal response at 12 months according to the criterion of proteinuria.27 These findings are similar to those found in our study, in which 58.7% of the population reached a response at one year.

Information regarding the impact of RTX on quality of life in the context of NL is scarce.29 The impact on quality of life in patients with SLE, mainly when there is joint involvement, severe renal manifestations, neuropsychiatric manifestations, damage accumulation, drug toxicity and the presence of other comorbidities, has been evaluated.28,31,32 At the time of this review, the only report that evaluated patients with SLE, the use of RTX and its impact on quality of life, which included patients with LN, found that its administration is associated with improvement in the EuroQol score.29 In our study, improvement was seen in all dimensions of the EuroQol, especially in pain, alteration of daily activities and mobility in patients with RLN and response to RTX (Fig. 1). Other studies have yielded similar data on the dimensions of quality of life of patients with SLE, especially in alteration of daily activities, anxiety and depression.30 The average HSU in our study was 0.83 in patients with RLN and response to RTX, configuring approximately 2.5 months more of time lived in a state of full health, compared with non-responders to RTX, indicating that in our cohort, which represents a group in which management of LN is difficult, is suggested an impact on quality of life in patients with LN in the context of refractoriness to treatment, which was improved with the use of RTX. These results support the effectiveness of RTX, as has been reported in other studies,24,25 and suggest a positive impact on quality of life in patients with RLN.

A limitation of the study is not being able to identify other determinants of the use of RTX, such as variability in the timely delivery of the medication or in its application on a regular basis, since in our health system it is difficult to precisely establish periods of non-use, characteristic of real-life conditions and fractionation of care.

In this study, which was subject to information and outcome biases, such biases were controlled with a selection of the population based on standardized classification criteria, both diagnostic and of non-response. In addition, only patients with complete data were included, and a substantial number of patients had to be excluded because of the missing data.

To date, our study is one of the largest cohorts of patients with RLN in Colombia, which allows us to take into consideration the results obtained in our study when evaluating patients with the same disease at the local level. Secondly, of the 27 patients who responded to RTX, 22 (81%) concomitantly received MMF at the induction time. The addition of MMF to RTX reflects the usual clinical practice; however, the response to RTX may be potentiated by the effect of MMF.

It is understood that complete renal response may take up to 2 years to be achieved, and that less than 40% of the patients achieve this result in the first 6 months. Despite this, and following the recommendations of EULAR/ERA-EDTA, patients without a partial response after 6–12 months and who experienced a change of treatment between MMF or CFM or vice versa, are defined as RLN. Taking into account this condition, the variable follow-up time could be another limitation of the study, given that we only had a follow-up period of 12 months and not of 18 months or more, as would be ideal.

Interpretation/conclusionsIn a cohort of Colombian patients with RLN, RTX could be effective to achieve a renal response at 6−12 months of treatment with respect to the outcome of proteinuria.

Our study also suggests that regardless of the SLEDAI and of the previous treatments (CYC and MMF), and despite having accumulated damage, patients who responded to RTX showed improvement in all dimensions of the EuroQol, especially in alteration of daily activities, pain and mobility, with a decrease between 1.9 and 2.5 months in the loss of full health status for each year lived with the disease compared with the patients who did not respond to RTX. Therefore, since the mean SDI of 1 in our study reflects a sick cohort with a poor baseline prognosis, it makes the impact found on quality of life more relevant.

Our study highlights that the evaluation of the impact on quality of life in addition to clinimetry is essential to establish treatments and adjust them in daily clinical practice.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they do not have any conflict of interest.