Co-infections between SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens is an important consideration for the treatment of patients with COVID-19. Aspergillus infections are part of this consideration since they present high morbidity and mortality. We present the case of a patient with COVID-19 and Aspergillus Fumigatus coinfection that evolves with brain death due to multiple heterogeneous lesions in the brain, which after a post-mortem biopsy found pathological lesions compatible with Aspergillus.

Las coinfecciones entre SARS-CoV-2 y otros patógenos son una cuestión importante para el tratamiento de los pacientes con COVID-19. Las infecciones por Aspergillus forman parte de esta consideración, ya que presentan elevada morbilidad y mortalidad. Presentamos el caso de un paciente con coinfección de COVID-19 y Aspergillus fumigatus que evolucionó a muerte cerebral debido a múltiples lesiones heterogéneas en el cerebro donde, tras biopsia post-mortem, se encontraron lesiones patológicas compatibles con Aspergillus.

COVID-19 is a disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. A significant number of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 develop secondary fungal infections, such as invasive pulmonary aspergillosis, that lead to serious complications. Invasive aspergillosis is nearly always localised in the brain, following haematogenous spread from pulmonary aspergillosis. This is one of the worst prognosis factors of invasive aspergillosis.

We present the case of a patient with COVID-19 who presented cerebral aspergillosis and progressed rapidly to brain death.

Case reportA 19-year-old man with a history of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura since childhood was transferred to the hospital with a diagnosis of liver failure secondary to Budd Chiari's syndrome. On physical examination, he presented stage 2 portosystemic encephalopathy, tense ascites and oedema in both lower limbs. A contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a heterogeneous liver with narrow suprahepatic veins with obstructed blood flow. These findings confirmed Budd Chiari’s syndrome, so erythropheresis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt were performed. The brain CT scan was unremarkable. The patient’s clinic course improved, but he was infected by SARS-CoV-2 during his hospital stay.

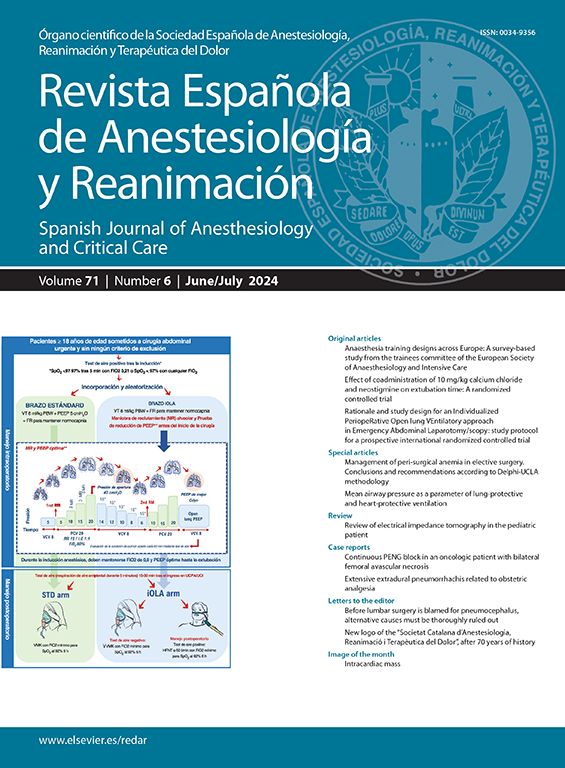

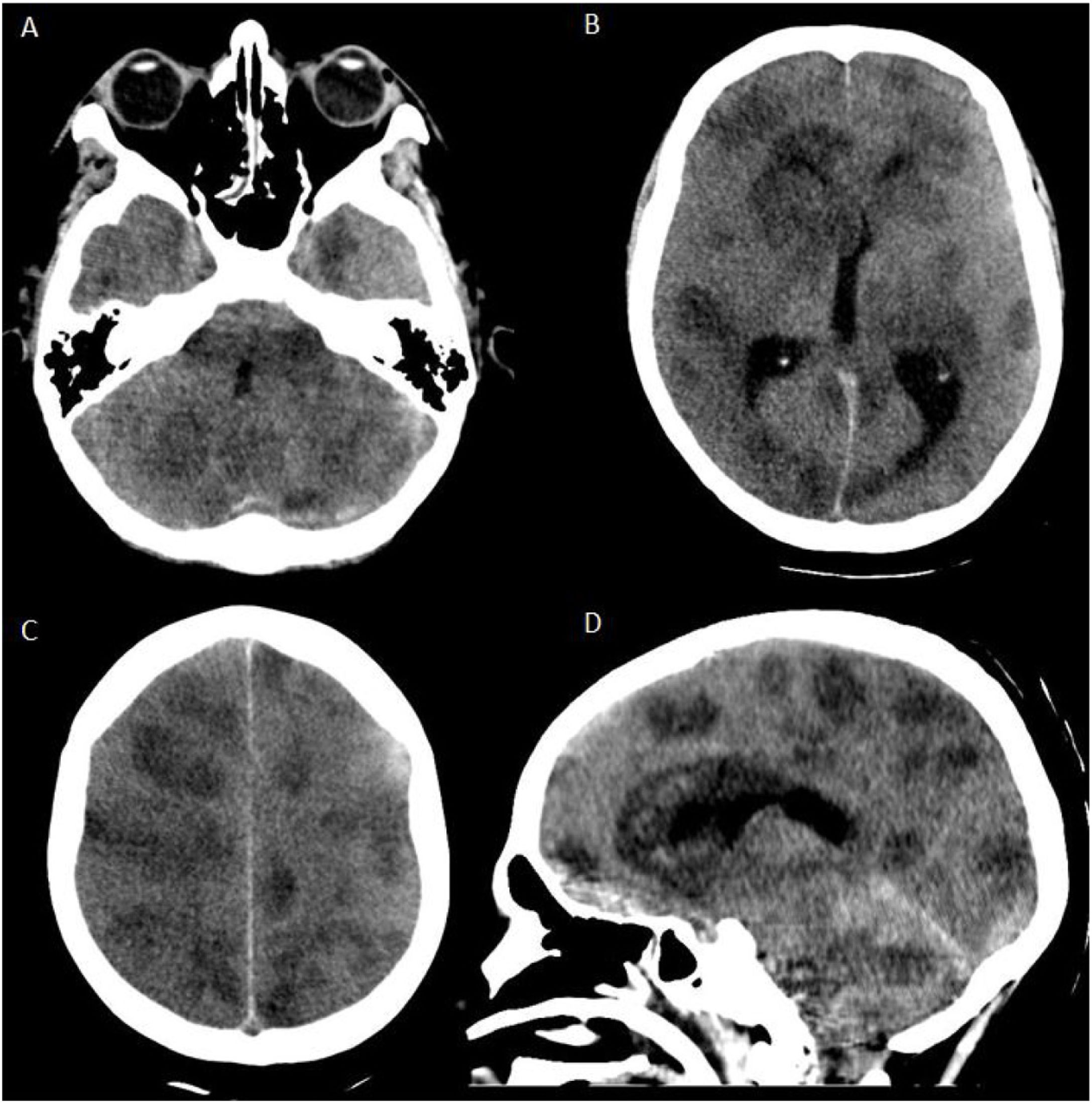

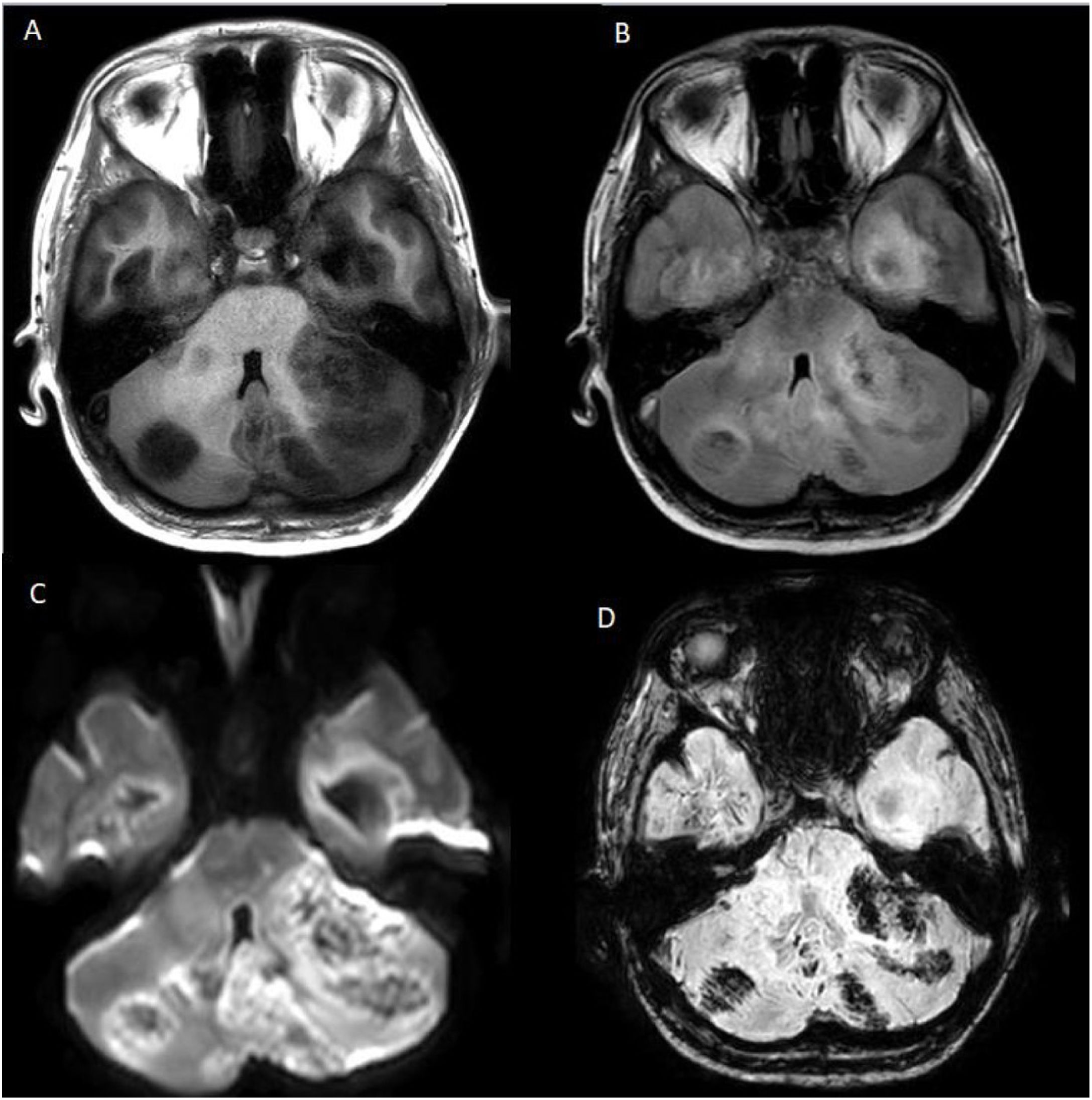

Two weeks later, he progressed to encephalopathy, fever, and respiratory failure and was intubated. The chest X-ray showed lobar consolidation in the left upper lung, so tracheal secretions were sampled for culture. The culture was positive for Aspergillus Fumigatus, so antifungal treatment with amphotericin b liposome was started. On the third day of mechanical ventilation, the patient presented bilateral fixed mydriasis. A brain CT was performed (Fig. 1), which showed several bilateral hypodense lesions with brain swelling and displacement of cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. Intracranial hypertension was treated with hypertonic sodium and mannitol, and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to characterize the images (Fig. 2). The MRI showed multiple supra- and infratentorial hyperintense lesions in T2, no uniform diffusion restriction on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and evidence of central haemorrhaging in susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI). There was no clear contrast enhancement or intracerebral blood flow secondary to severe intracranial hypertension (Fig. 3).

Brain CT showing multiple supra- and infratentorial hypodense lesions plus swelling and alteration of the interface between grey-white matter. Sagittal view (d) shows herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. At the level of the brainstem (A, D), absence of peritroncal cisterns and distortion of the fourth ventricle are observed.

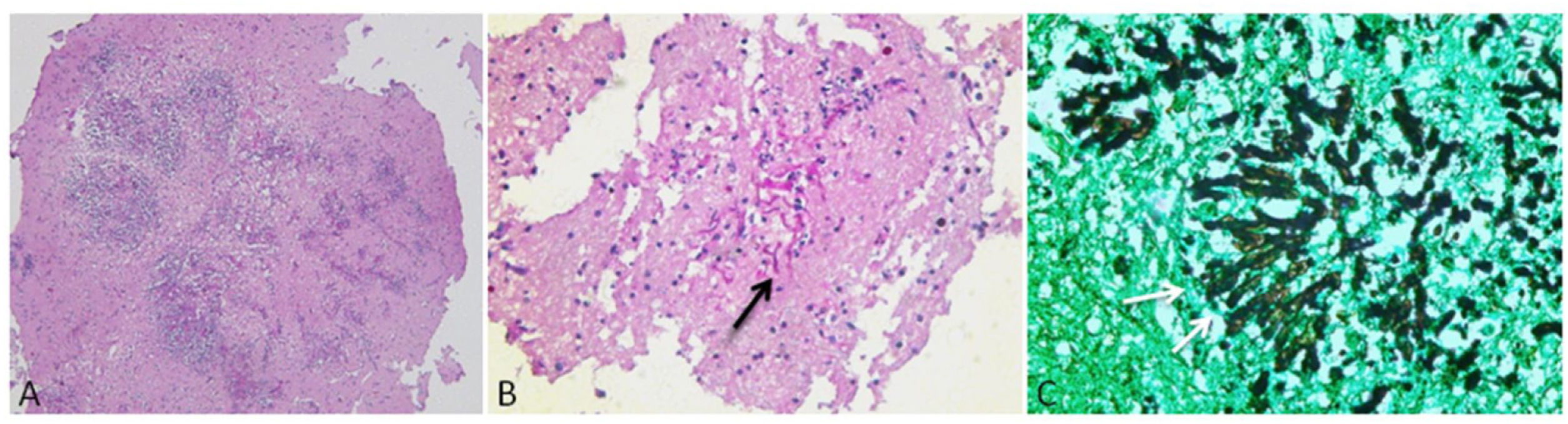

The patient remained unresponsive without sedation. Cranial nerve examination showed fixed dilated pupils, absent corneal, oculocephalic and cough reflexes, no spontaneous breathing, and absent motor response to central and peripheral noxious stimulation. Apnoea testing was deemed unsafe due to hypoxia (moderate ARDS). The patient was declared brain dead after clinical tests had been performed and 2 transcranial doppler showed a systolic spike in both the middle cerebral artery and basilar artery, as required by to national regulations. A minimally invasive post mortem biopsy of cerebral tissue through the trans-nasal route and lumbar puncture were performed, with the family’s consent. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was remarkable for hypoglycorrhachia, leucorrhachia and high lactic acid. Aspergillus Fumigatus was identified in CSF mycologic culture. Histological examination revealed areas of necrosis, perivascular neutrophils, and septate mycelia with 45° angle branching that invaded the brain parenchyma, suggesting the presence of Aspergillus. (Fig. 4)

The final diagnosis in this case was cerebral aspergillosis secondary to invasive fungal infection in a patient infected with SARS-CoV-2.

DiscussionCentral nervous system (CNS) infection by Aspergillus is a rare but fatal condition that tends to occur as a result of hematogenous dissemination (10%–20%)1 in immunocompromised patients or by local extension or direct inoculation secondary to trauma in immunocompetent hosts. Neuroaspergillosis in immunosuppressed patients may have several consequences, such as cerebral infarction, haemorrhage, encephalomalacia, multiple or isolated abscess, and meningitis.2 Brain imaging is essential for diagnosis, but there are no specific radiological findings for neuroaspergillosis. CT is probably the first study to be performed, but it cannot distinguish fungal from bacterial abscesses. Fungal abscesses are often multiple, whereas bacterial abscesses are single, do not involve the deep grey matter, and spare the basal ganglia.4 Patients with CNS aspergillosis secondary to direct invasion from the sinuses develop single lesions in the frontal or temporal lobe, while patients with hematogenous dissemination may present single or multiple lesions at the grey–white junction. Cerebral cortical and subcortical infarction, with or without haemorrhagic transformation and mycotic aneurysms, typically develop as result of angioinvasion,3 and may be followed by conversion to an infected area with abscess formation.

Some authors have reported CNS damage in autopsies of COVID-19 infected patients.4–6 Glial activation, mild meningeal inflammation, and fresh infarcts with variable detection of COVID-19 RNA and/or antigens were found in these patients; however co-infections were not reported in autopsy series in brain tissue.

Although more statistical data are needed, studies in co-infections in SARS-CoV-2 patients7,8 have reported that a significant number of hospitalized patients develop secondary systemic mycoses that leads to serious complications and even death.9 In severe cases, the risk of invasive fungal infections is high, not only due to the clinical situation of the patient and the need for invasive care, but also to the immune alterations caused by SARS-CoV-2. Patients with severe COVID-19 have higher pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels, fewer CD4 and CD8 cells, and less interferon-gamma expression by CD4 cells than those with more moderate disease. Cytokine release syndrome and immune exhaustion may predispose to fungal superinfection.10

In this report, we discuss the case of a 19-year-old man with a history of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura since childhood, who was admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of liver failure secondary to Budd Chiari's syndrome. He became infected with SARS-CoV-2, and was later diagnosed with brain death in the context of neuroaspergillosis secondary to invasive aspergillosis. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a case of COVID-19 and neuroaspergillosis. Early diagnosis of neuroaspergillosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion due to the absence of typical clinical symptoms or CSF findings. Clinical manifestations are usually dramatic and tend to progress rapidly, so it is important to identify the characteristic features of neuroaspergillosis on CT and MRI in order to start the appropriate therapy as soon as possible.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.