Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome is an acute neurological disorder characterized by variable symptoms and radiological images characteristic of vasogenic parietal-occipital edema. It is associated with clinical conditions such as high blood pressure, infection/sepsis, or cytotoxic/immunosuppressive drugs, among others. It is characterized pathophysiologically by endothelial damage with breakdown of blood-brain barrier, cerebral hypoperfusion, and vasogenic edema.

The cases are presented on 2 critical COVID-19 patients who were admitted to pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation and who, after removing sedation, developed acute and reversible neurological symptoms consisting of epilepsy and encephalopathy, associated with hyperintense subcortical lesions on brain magnetic resonance imaging compatible with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus would activate an inflammatory response that would damage brain endothelium. It could be triggered by cytokine release, as well as by direct viral injury, given that endothelium expresses ACE2 receptors. It could explain the possible association between posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and COVID-19.

El síndrome de encefalopatía posterior reversible es un trastorno neurológico agudo caracterizado por una sintomatología variable e imágenes radiológicas características de edema vasogénico parietooccipital. Está asociado a condiciones clínicas como hipertensión arterial, infección/sepsis o fármacos citotóxicos/inmunosupresores, entre otros. Se caracteriza fisiopatológicamente por daño endotelial con rotura de la barrera hematoencefálica, hipoperfusión cerebral y edema vasogénico.

Presentamos 2 casos de pacientes críticos COVID-19 que ingresaron por neumonía con necesidad de ventilación mecánica y que tras retirar la sedación desarrollaron clínica neurológica aguda y reversible consistente en epilepsia y encefalopatía, asociada a lesiones subcorticales hiperintensas en la resonancia magnética cerebral compatibles con síndrome de encefalopatía posterior reversible.

El coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 activaría una respuesta inflamatoria que produciría daño en el endotelio cerebral. Este último podría ser desencadenado por la liberación de citocinas, así como por una lesión viral directa, dado que el endotelio expresa receptores ACE2. Esto podría explicar la posible asociación entre el síndrome de encefalopatía posterior reversible y la COVID-19.

Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) is a clinical and radiological entity first described by Hinchey et al. in 1996 in which up to 40% of cases require critical care due to severe complications such as status epilepticus, stroke or intracranial hypertension1,2.

This syndrome is clinically characterised by headache, decreased level of consciousness, seizures, visual disturbances and neurological deficits. Radiological findings include vasogenic cerebral oedema predominantly in the white matter of the parieto-occipital regions1,2. In addition, haemorrhagic complications, such as petechial haemorrhages and intraparenchymal haematomas, are associated in 15%–20% of cases3.

PRES is associated with various clinical conditions, such as renal failure, arterial hypertension (AHT), infection/sepsis, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, autoimmune diseases or cytotoxic/immunosuppressive drugs, among others. It is characterised pathophysiologically by acute endothelial damage with blood–brain barrier breakdown and vasogenic brain oedema, although its pathogenesis is not fully understood4,5.

Fugate et al. proposed as diagnostic criteria the association of acute neurological symptoms, image of focal vasogenic cerebral oedema and reversibility of findings6.

Imaging tests are important in the differential diagnosis, which includes progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL), encephalitis, mitochondrial encephalopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), among others. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more accurate than computed tomography (CT) for diagnosis1,2.

Treatment is symptomatic. Antihypertensives and/or anticonvulsants and elimination of the underlying cause are required. If there are no serious complications, the prognosis is favourable1,2.

Case presentationCase 1The patient was a 66-year-old male, with a history of AHT and dyslipidaemia, who was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit of the Anaesthesiology Department with SARV-CoV-2 coronavirus pneumonia requiring mechanical ventilation.

During the first days of admission, the patient presented a multi-organ dysfunction syndrome that required the use of vasoactive amines together with renal replacement therapy and continuous venovenous haemofiltration due to anuric acute renal failure with peak creatinine values of 2.5mg/dl. From the respiratory point of view, several prone decubitus sessions were necessary in the first 10 days and a tracheotomy was performed to advance respiratory weaning.

In accordance with the unit’s protocol, he was administered lopinavir–ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, ceftriaxone and levofloxacin for 5 days, in addition to dexamethasone for 10 days and low molecular weight heparin at anticoagulant doses due to maximum D-dimer levels of 5630ng/ml. Between the first day of admission and the seventh, he received immunomodulatory treatment with tocilizumab, baricitinib and interferon beta, with ferritin values of 3485ng/ml, IL-6 of 413pg/ml, CRP of 138mg/dl and lymphocytes of 120U/mm3.

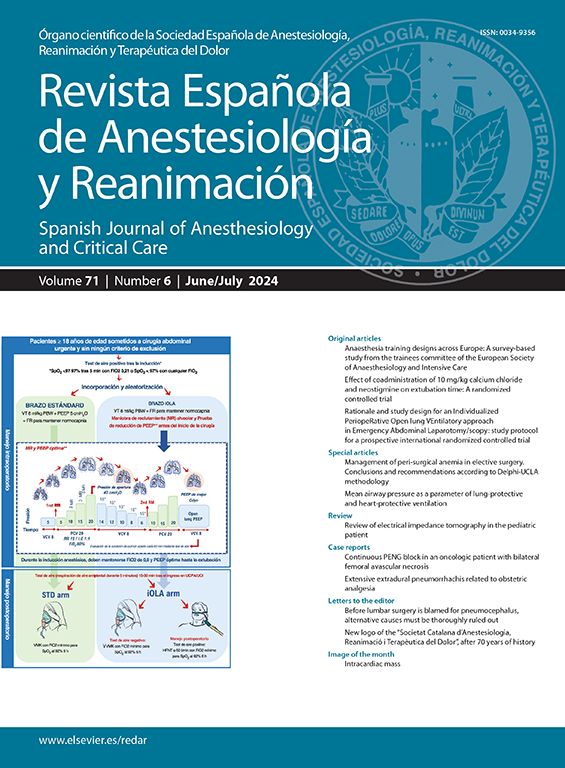

He required sedoanalgesia with midazolam at a dose of 20mg/h, fentanyl 100g/h and propofol 150mg/h. Due to respiratory improvement, on day 13 of evolution, sedation was withdrawn and during the following 24–48h a low level of consciousness persisted with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 9, so an electroencephalogram was requested, which reported mild encephalopathy. The patient evolved favourably, with an improved level of consciousness and a GCS of 14. However, 16 days after admission, he began to experience right hemispheric focal seizures characterised by left hemifacial clonus with secondary generalisation, which subsided with diazepam 10mg and levetiracetam 1.5g iv every 12h. After stabilisation, a CT scan was performed, which reported bilateral parietooccipital subcortical hypodense lesions, predominantly on the right (Fig. 1). The differential diagnosis between ischaemic lesions due to low cardiac output and a PRES was raised, for which reason a CT angiography of the supra-aortic trunks and an MRI were requested.

At 24h the same neurological symptoms recurred, requiring a new dose of diazepam, to which lacosamide 200mg iv every 12h was added.

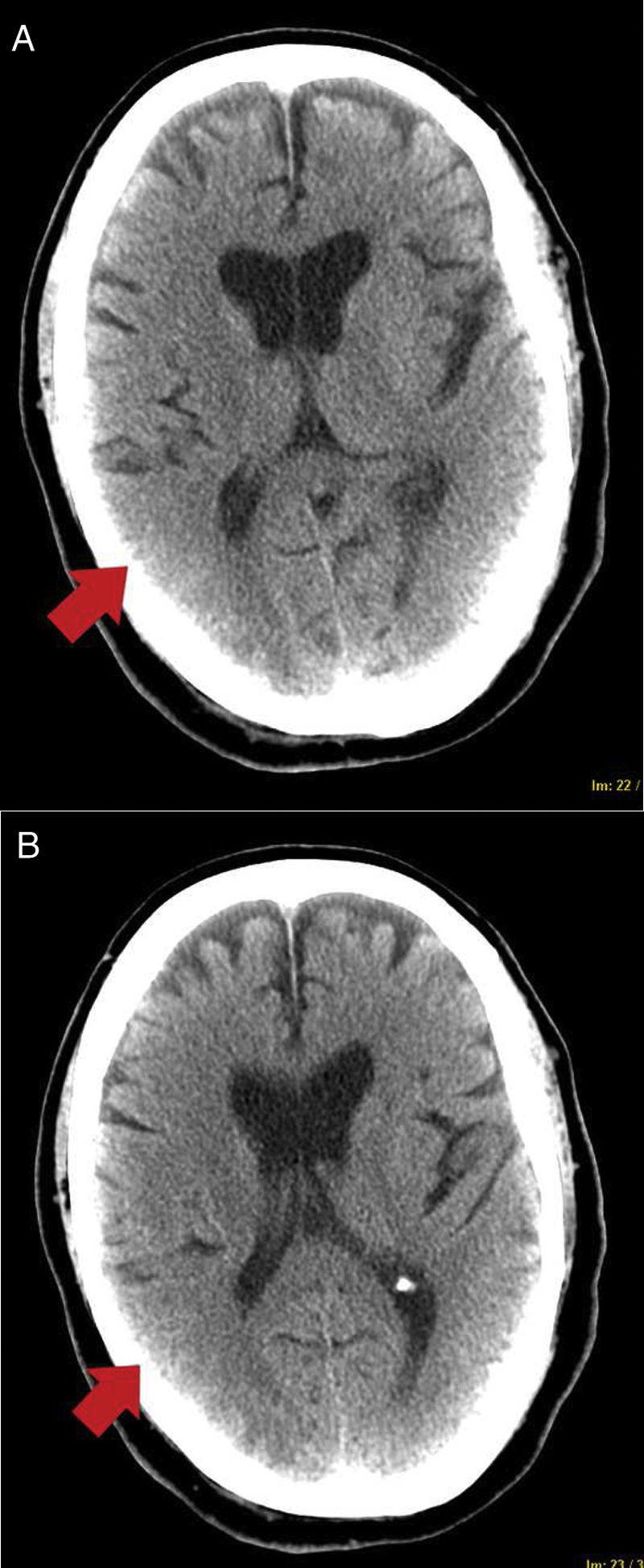

Electroencephalograms reported focal intercritical abnormalities leading to complex partial seizures located in the right hemisphere. CT angiography was normal and MRI showed subcortical T2 hyperintense lesions in the parietooccipital border territory. As a first possibility, the diagnosis of PRES (Fig. 2) was raised in the context of severe COVID-19 infection.

After the combination of antiepileptic drugs and improvement of the viral infection, no new seizures appeared. The patient evolved satisfactorily, with mild bradypsychia and a tendency to left ocular deviation that resolved progressively, without other neurological focality.

Case 2The patient was a 64-year-old male, hypertensive and dyslipidaemic, who was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit due to COVID-19 pneumonia. In the first few days he developed a multi-organ dysfunction syndrome that required mechanical ventilation, noradrenaline and dobutamine perfusion, in addition to treatment with continuous venovenous haemofiltration due to anuric renal failure with maximum creatinine levels of 2.7mg/dl.

He was treated with lopinavir–ritonavir, hydroxychloroquine, ceftriaxone and levofloxacin for 5 days, in addition to dexamethasone for 10 days and low molecular weight heparin at anticoagulant doses due to peak D-dimer levels of 5666ng/ml, in addition to immunomodulatory treatment with tocilizumab, baricitinib and interferon beta. Blood tests showed ferritin of 4483ng/ml, CRP of 180mg/dl and lymphocytes of 70U/mm3.

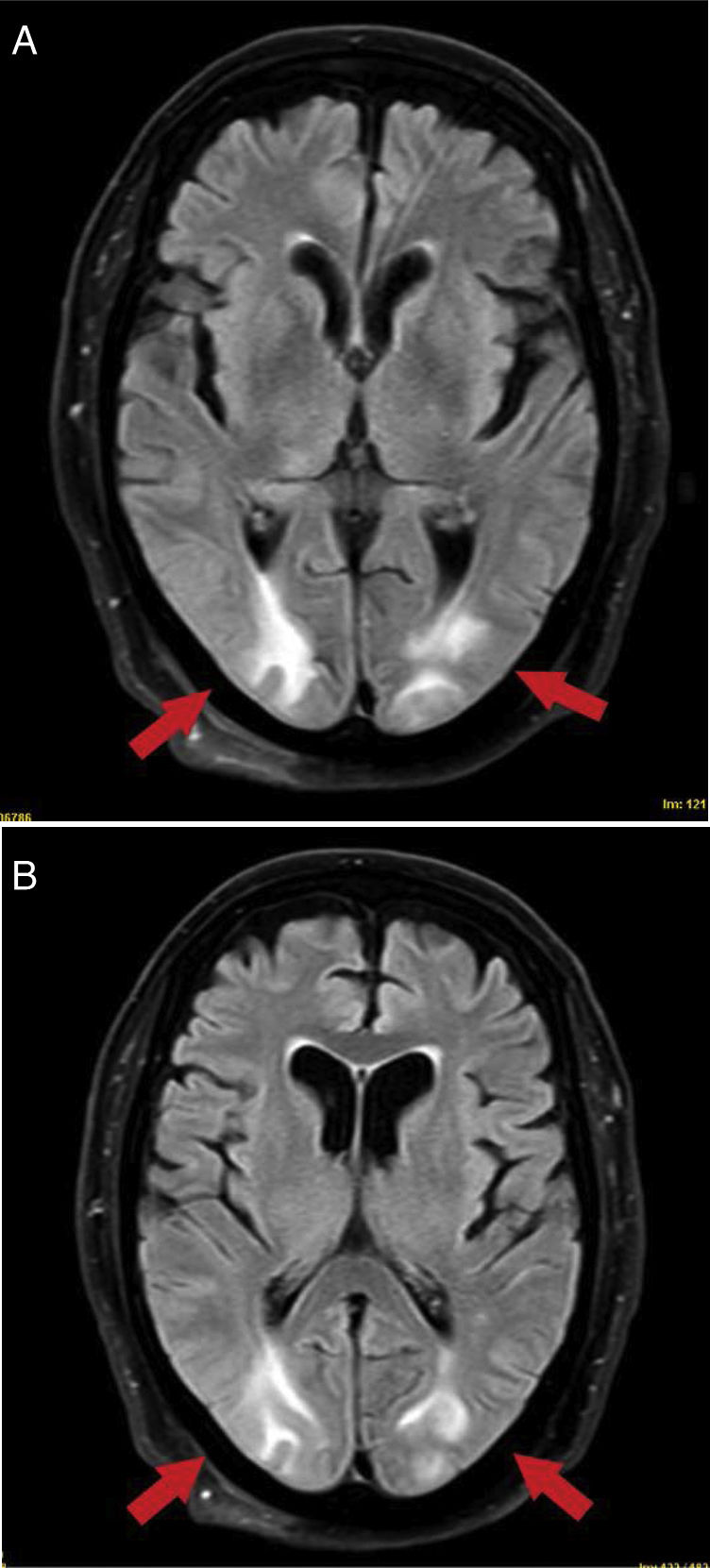

He received sedoanalgesia with midazolam at a dose of 20mg/h and fentanyl 100g/h for 13 days. On the 14th day of evolution, the respiratory and haemodynamic symptoms had improved, so the sedation was withdrawn and he progressively presented a tendency towards hypertension with maximum blood pressure of 170/100mmHg, associated with clinical signs of decreased level of consciousness with a GCS of 5. An electroencephalogram was requested, which ruled out status epilepticus, confirming severe encephalopathy. A brain CT scan was performed, which reported bilateral supratentorial parenchymal parenchymal haematomas with perilesional oedema, and areas of subarachnoid and petechial haemorrhages with perivascular predominance (Fig. 3). Neurosurgery ruled out surgical treatment.

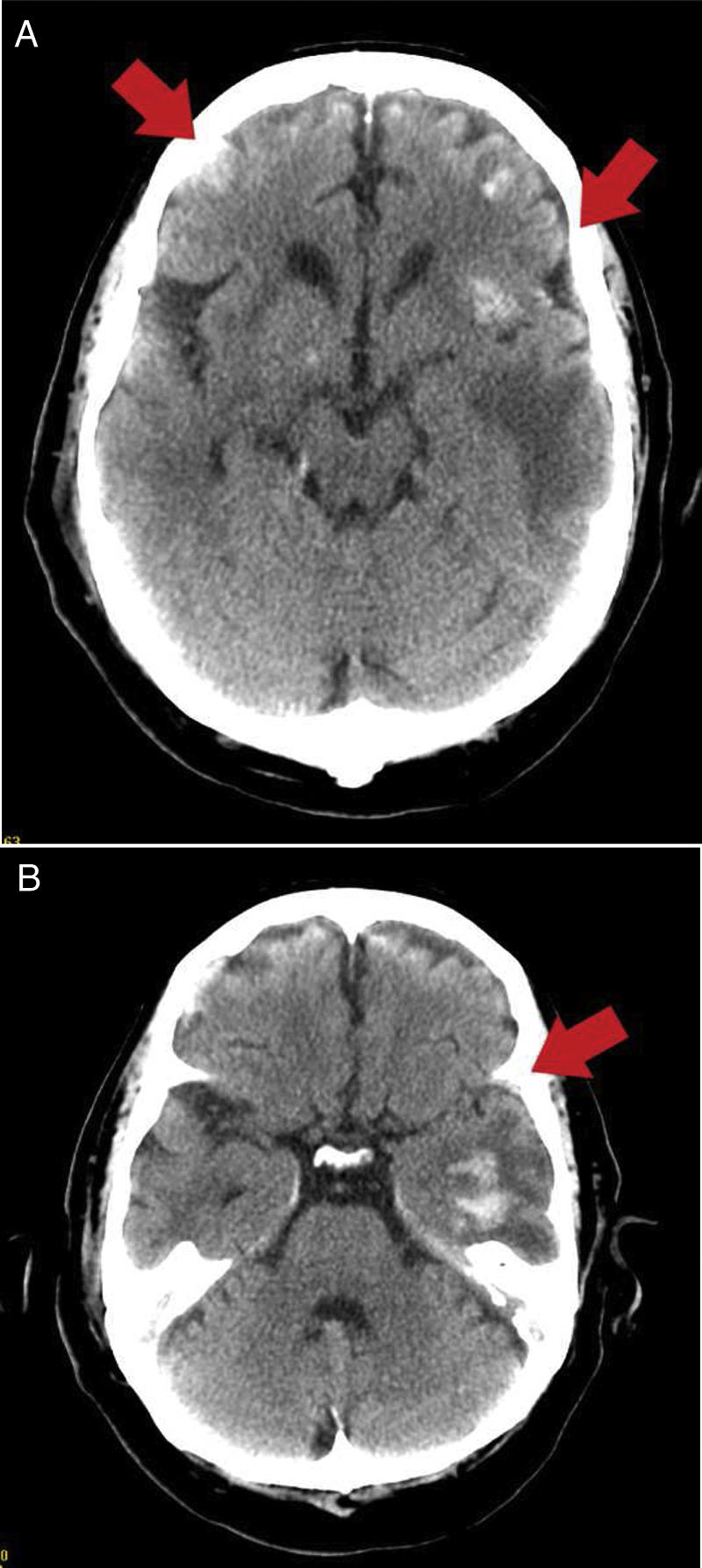

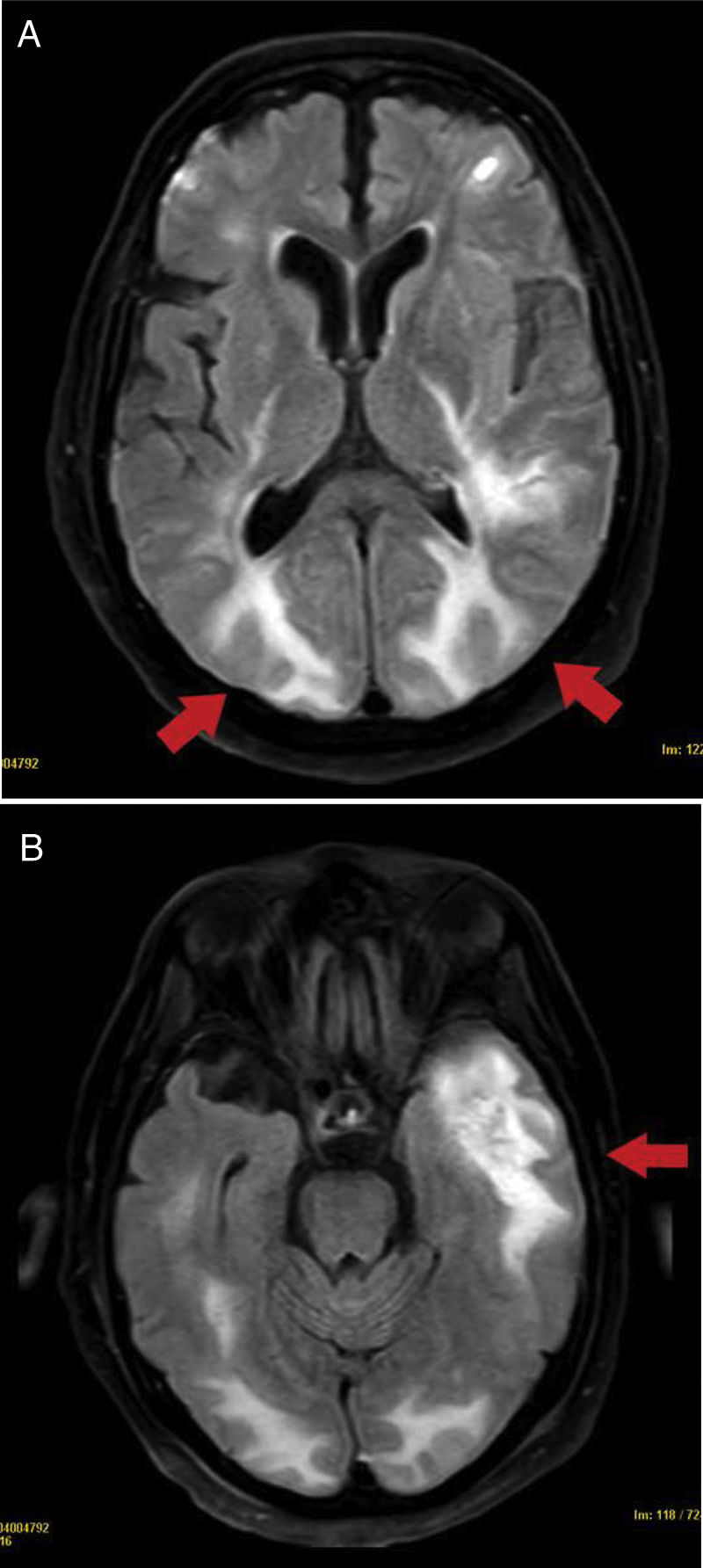

The study was completed with an MRI, which showed bilateral supratentorial lesions with vasogenic oedema, mainly in the bilateral occipital and left temporal region, indicative of PRES (Fig. 4). In addition, the lesions had a haemorrhagic and necrotising component, which made it impossible to rule out necrotising encephalitis.

In the following days, the evolution was favourable with supportive treatment and control of hypertension with iv labetalol and later with oral losartan. He was discharged with a GCS of 15 and no neurological deficits. The control MRI did not detect white matter involvement with a PRES pattern.

DiscussionSeveral etiopathogenic theories have been proposed for this syndrome. The most widely accepted proposes that the increase in blood pressure results in impaired cerebral autoregulation. However, 30% of cases have normal or slightly elevated blood pressure values that do not exceed the autoregulatory limit. Another theory is that endogenous circulating toxins, such as pre-eclampsia/eclampsia or infection/sepsis, or exogenous toxins, such as cytotoxic/immunosuppressive drugs and pro-inflammatory cytokines cause endothelial dysfunction2.

Several pathophysiological mechanisms triggered by the coronavirus could explain the endothelial dysfunction associated with PRES. The latter could be triggered by cytokine release with the development of an exaggerated systemic response, as well as by direct viral injury by SARS-CoV-2, since the nervous system endothelium expresses ACE receptors3,7.

In a recent study of early post-mortem brain MRI findings in COVID-19, subcortical oedematous changes indicative of PRES, were visualised in one patient8.

Other viruses, such as parainfluenza or Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, have been associated with the development of PRES1,3. PRES in SARS-CoV-2 infection has not yet been well described, although it appears that COVID-19 is associated with multiple risk factors that have been observed in this entity3,7.

In our cases, the reversible clinical and radiological features supported the diagnosis of PRES. We know that SARS-CoV-2 infection itself can produce endothelial damage in the central nervous system, however, we cannot rule out the contribution of other clinical conditions present in critically ill COVID-19 patients, such as acute renal failure, multi-organ dysfunction syndrome and immunomodulatory treatment, including tocilizumab, which has been linked to the syndrome9.

In the first case, ischaemic aetiology was ruled out by CT angiography and hypertensive encephalopathy, as the patient’s blood pressure remained stable.

However, in the second patient, fluctuations with peaks of hypertension were recorded, which could have acted as a risk factor for PRES associated with haemorrhagic complications, in addition to the possible contribution of treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin at anticoagulant doses in these patients10. We dismissed the diagnosis of necrotising encephalitis given the reversible nature of the lesions and the radiological pattern on MRI without involvement of the thalami.

In conclusion, PRES was probably multifactorial: renal failure, severe SARS-CoV-2 infection, immunosuppression and/or cytotoxic drugs. Further studies are needed to determine the possible relationship with COVID-19. We recommend keeping it in mind as a cause of acute neurological symptoms in these patients in order to detect it early, given its reversible nature.

FundingThis research has not received specific support from the public, commercial or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.