SARS-CoV-2 infection has evolved into a pandemic and a Public Health Emergency of International Importance that has forced health organizations at the global, regional and local levels to adopt a series of measures to address to COVID-19 and try to reduce its impact, not only in the social sphere but also in the health sphere, modifying the guidelines for action in the health services. Within these recommendations that include the Pain Treatment Units, patients with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection may be waiting for medical consult or interventional procedures for the management of chronic pain refractory to other therapies. A series of guidelines aimed at reducing the risk of infection of health personnel, other patients and the community are included in this manuscript.

La infección por SARS-CoV-2 ha evolucionado hasta convertirse progresivamente en una pandemia y en una emergencia de salud pública de importancia internacional que ha obligado a las organizaciones de salud a nivel mundial, regional y local a adoptar una serie de medidas para hacer frente a la COVID-19 e intentar disminuir su impacto, no solo en el ámbito social sino también en el ámbito sanitario, modificándose las pautas de actuación en los servicios de salud. Dentro de estas recomendaciones, que incluyen las unidades de tratamiento del dolor, los pacientes con sospecha o infección confirmada por SARS-CoV-2 pueden encontrase en situación de espera para consulta médica o técnicas invasivas para el manejo de dolor crónico refractario a otras terapias. Se recogen en este manuscrito una serie de pautas encaminadas a disminuir el riesgo de infección del personal de salud, de otros pacientes y de la comunidad.

The first report of a series of patients in China with a pulmonary infection of initially unknown aetiology and clinical features similar to viral pneumonia emerged at the end of 2019. Deep sequencing analysis from lower respiratory tract samples identified a new type of virus belonging to the family Coronaviridae called SARS-CoV-2 as the agent responsible for the disease that was renamed COVID-191. Since then, millions of cases have been identified worldwide. The World Health Organization classified this infection as a pandemic, and it later developed into a public health emergency of international importance2,3.

Although the vast majority of coronaviruses are responsible for mild upper respiratory tract infections in immunocompetent adults, they can also cause more serious conditions, such as severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and sepsis in patients with certain risk factors, namely, cardiovascular disease (10.5%), diabetes (7.3%), chronic respiratory disease (6.3%), high blood pressure (6%) or cancer (5.6%)1,2.

Experts currently believe that person-to-person transmission of the infection occurs mainly through respiratory droplets and when mucous membranes (oral, ocular and nasal) come into contact with contaminated material. It can also be transmitted by aerosols when these are produced during certain therapeutic procedures. According to estimates, a single case of COVID-19 produces between 2 and 3 new cases2,4. The mean incubation period is between 5.2 and 12.5 days, although incubation periods of 24 days have been observed in some cases1.

The potential repercussions of COVID-19 have prompted international, regional and local health organizations to adopt a series of containment measures in an attempt to reduce its impact5 on both society and healthcare services. These measures include changing health service action guidelines and promoting strategies such as eHealth6, a remote care resource that has been introduced into several specialist fields, among them, pain management. Ehealth portals have now become an essential part of scheduled, non-urgent medical consultations (clinical course, start and follow-up of medical treatment, psychological interventions, etc.)6. Ehealth services, however, are not suitable in certain situations, such as in patients with chronic pain refractory to medical treatment in which direct contact is indicated, despite the corresponding risk of transmission and contamination.

All these interventions and different approaches to patient-doctor interaction have made it necessary to establish a series of clinical guidelines to reduce the risk of infection for patients, health personnel and the community as a whole. These recommendations cover most aspects of healthcare, from the initial evaluation (either online or in person) to the performance of non-surgical invasive procedures for the control of chronic pain, and can also be useful in clinical situations involving a risk of infection by microorganisms that are similar to the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Few articles have been published on the practical approach to and management of patients with chronic pain during the COVID-19 pandemic. To promote safe clinical practice in this context, we assembled the most relevant indications and adapted them for use in our setting.

General objectivesThese guidelines have been drawn up to provide a framework that will allow healthcare professionals responsible for the management of patients with chronic pain to mitigate the risk of contamination to both healthcare providers and patients, preserve and optimize resources, and guarantee access to specialized medical services. The specific issues addressed include in-person or remote (eHealth) patient care, general and specific interventional risks, problems relating to patient flow and staff organisation, and the use of resources during the COVID-19 pandemic7.

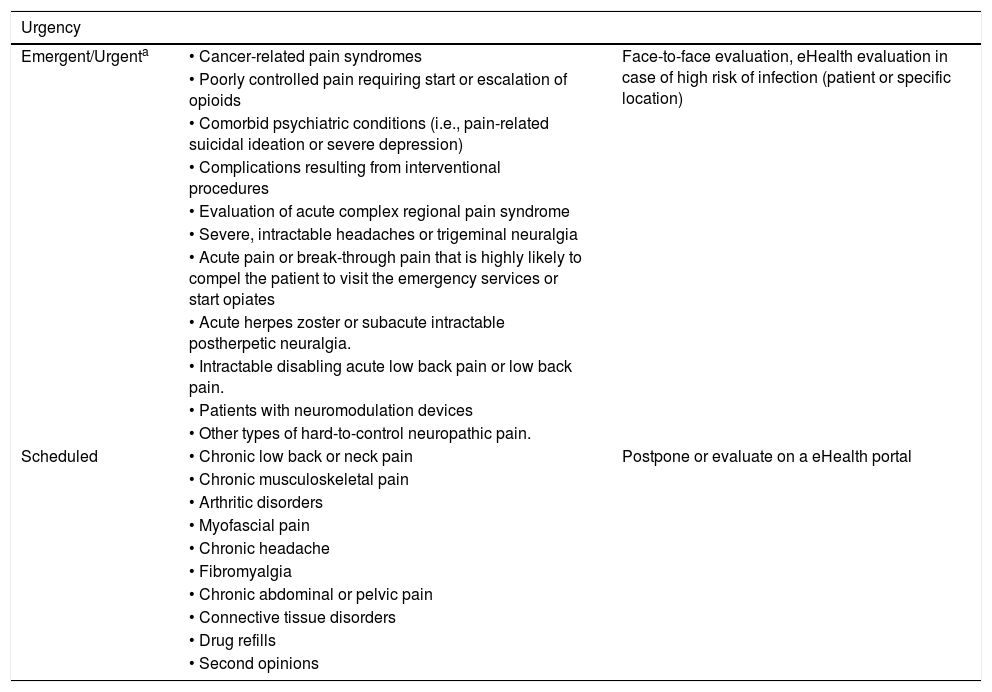

Clinical scenarios TriageEven during the COVID-19 pandemic, pain management units must prioritise cases that cannot be managed through eHealth portals, i.e., patients in whom conventional therapies have failed and who need to be evaluated by a specialist who will probably need to perform an invasive pain management procedure during the consultation. Patients should be prioritised on the basis of their need for treatment using both medical criteria and logistic considerations. In the case of patients with chronic pain, the following situations should be considered (Table 1)8:

- •

Symptom worsening.

- •

Psychiatric symptoms associated with chronic pain (e.g., severe pain-related depression).

- •

Social problems derived from the lack of pain therapy (e.g., caregiver needed to care for dependent persons with disabling pain).

- •

High level of pain accompanied by functional impairment.

- •

High probability that the face-to-face visit/procedure will provide a significant benefit.

- •

Likelihood that the patient will call emergency services that are already overstretched by the pandemic or will have to start undesirable therapies (e.g., opioids).

- •

Need for physical examination.

- •

Employment/work status: first responders (police, fire-fighters, etc.) must be given priority.

Pain treatment unit triage based on clinical criteria during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Urgency | ||

|---|---|---|

| Emergent/Urgenta | • Cancer-related pain syndromes | Face-to-face evaluation, eHealth evaluation in case of high risk of infection (patient or specific location) |

| • Poorly controlled pain requiring start or escalation of opioids | ||

| • Comorbid psychiatric conditions (i.e., pain-related suicidal ideation or severe depression) | ||

| • Complications resulting from interventional procedures | ||

| • Evaluation of acute complex regional pain syndrome | ||

| • Severe, intractable headaches or trigeminal neuralgia | ||

| • Acute pain or break-through pain that is highly likely to compel the patient to visit the emergency services or start opiates | ||

| • Acute herpes zoster or subacute intractable postherpetic neuralgia. | ||

| • Intractable disabling acute low back pain or low back pain. | ||

| • Patients with neuromodulation devices | ||

| • Other types of hard-to-control neuropathic pain. | ||

| Scheduled | • Chronic low back or neck pain | Postpone or evaluate on a eHealth portal |

| • Chronic musculoskeletal pain | ||

| • Arthritic disorders | ||

| • Myofascial pain | ||

| • Chronic headache | ||

| • Fibromyalgia | ||

| • Chronic abdominal or pelvic pain | ||

| • Connective tissue disorders | ||

| • Drug refills | ||

| • Second opinions |

In purely practical terms, however, the following priority clinical situations should be taken into consideration7:

- •

Intractable cancer pain.

- •

Acute herpes zoster or subacute intractable postherpetic neuralgia.

- •

Acute and severe low back pain or sciatica.

- •

Trigeminal neuralgia or other facial neuralgia or headaches that cause severe pain.

- •

Complex regional pain syndrome.

- •

Other types of hard-to-control neuropathic pain.

- •

Breakthrough pain in patients with patient-controlled analgesia pumps or neuromodulation devices.

- •

Other types of severe, hard-to-control pain, after carefully assessing the risk-benefit ratio.

- •

Patients with neuromodulation implants (posterior spinal cord/peripheral/subcutaneous or dorsal root ganglion stimulators and intrathecal drug infusion devices).

During the health crisis, the following strategies should be considered in patients with chronic pain who need to consult a specialist, usually in a hospital pain management unit:

- •

Promote non-face-to-face, telephone or eHealth consultation as far as possible, provided this does not undermine therapeutic effectiveness or symptom control. Patients must always agree to receive online or video-based care. The non-face-to-face consultation should include both the patient interview and a review of the tests ordered. Mechanisms must be implemented to enable online access to test results wherever this service is not already available.

- •

In face-to-face consultations, the following is important:

- o

Patients should be seen and treated as quickly as possible in order minimize the time spent in waiting rooms, and consultation and procedure rooms. To achieve this, the appointment schedule should be carefully planned and adhered to as far as possible.

- o

Whenever possible, patients, particularly priority cases, should be evaluated, diagnosed and treated in a single session.

- o

Never make overlapping appointments. Schedule appointments to avoid crowding in common areas and to allow time to disinfect between patients. This may mean reducing the number of daily appointments.

- o

Patients should wait in rooms that are large enough to follow the 2 m safety rule. The rooms must be equipped with a hand sanitizer and instructions for use. If this is not possible, allow patients to wait in their vehicle, and notify them by phone when it is time for their appointment.

- o

Patients must always wear a surgical mask at all times.

- o

Patients may not be accompanied by another person, unless they are dependent on a carer, in which case only 1 carer will be allowed per patient.

- o

Always ask patients about the presence of symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection (fever, cough, general malaise, anosmia) and whether they have had a PCR or blood test to detect COVID-19 infection.

- o

All waiting rooms must be equipped with an infrared thermometer to take the temperature of all patients before they can go in to the consultation room.

- o

The use of transparent protection screens between secretarial staff/doctors and patients can be considered.

- o

Clinicians must use personal protective equipment during examinations: disposable gown, surgical mask, goggles or face shield, and disposable gloves.

- o

All surfaces in treatment rooms, including tables, gurneys, chairs, doorknobs, and other equipment, must be disinfected between patients.

- o

Known COVID + patients must follow a special circuit established by each hospital.

- o

At the end of the consultation, patients requiring follow-up must be assigned to either the eHealth portal, provided this is feasible, or a face-to-face visit, in which case they must be given an appointment straight away, without the need to wait in reception.

- o

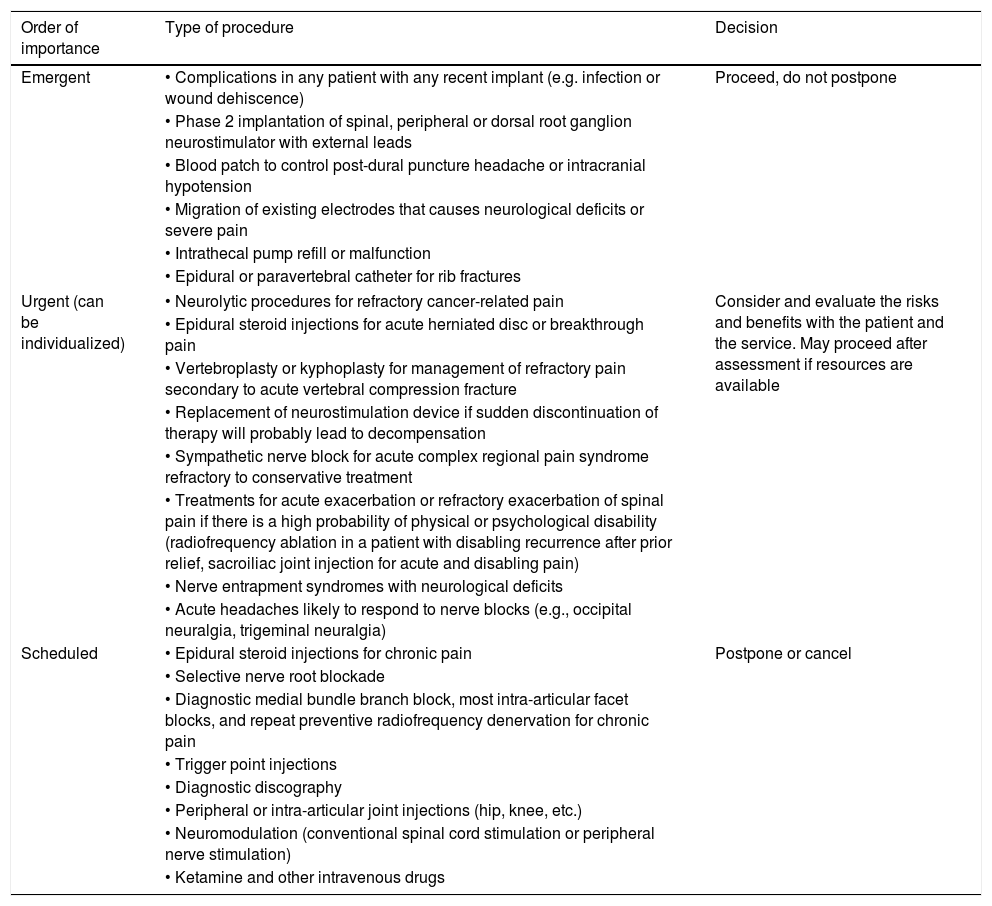

Interventional procedures should be reserved for priority patients, and should be scheduled after carefully evaluating the risk in each case. All patients should be asked to sign a consent form informing them of the risk of contact with COVID-19 in the hospital environment (Table 2)8.

- •

Hospital outpatient invasive procedure room:

- -

Minimise as far as possible patient circulation and the length of stay in care areas.

- -

Establish as much physical distance between patients as possible; if possible, avoid the presence of more than 1 patient at a time in any given area. If this is not possible, patients must follow the 2 m separation rule.

- -

Patients and their carers, as applicable, must wear a surgical mask on arrival at the area.

- -

Only 1 carer, who must be asymptomatic, should be allowed per patient. Carers with fever or symptoms will not admitted.

- -

Carers should wait in rooms that are large enough to follow the 2 m safety rule. The rooms must be equipped with a hand sanitizer and should not contain any waiting room accessories, such as flyers, magazines, etc. If this is not possible, the carer must be allowed to wait in their vehicle, and must be notified by phone when it is time for them to collect the patient.

- -

All procedures must be performed by an experienced practitioner.

- -

Precautions to prevent contact and droplet contamination must be taken when performing the procedure, and clinical personnel must wear FFP2/FFP3 masks (particularly in aerosol-generating procedures), goggles or face shield, waterproof gown, and double gloves.

- -

There should be enough space in the area to don and doff PPE safely and to perform proper hand washing.

- -

All equipment (nerve block and epidural needles, radiofrequency needles, etc.) and infusion sets or syringes must be prepared before starting the procedure in order to minimise the need for opening and handling trolleys. Use disposable material whenever possible. Likewise, to minimise the need to open drug carts, any medication that will or might be required must be prepared and placed on a large tray.

- -

Minimize the number of personnel present during the procedure, but ensure there is immediate access to additional personnel should they be required.

- -

Pre-procedural administration of midazolam or long-acting benzodiazepines should be avoided. If these cannot be avoided, administer the lowest possible dose in each case. The aim is to reduce excessive muscle relaxation or respiratory depression that will cause discharge delays and prolong the presence of the patient in high risk areas and in the hospital in general.

- -

Monitoring should be tailored to the patient's status and the analgesic technique to be performed. The standard monitoring techniques recommended by the ASA and SEDAR (continuous ECG, NIBP, SatO2) should be used.

- -

If point-of-care devices such as ultrasound or telemetry systems are used, the main unit and cable must be encased in plastic to minimise equipment contamination.

- -

Patients should recover from the intervention in the procedure room itself (avoid moving them to another unit). Post-intervention recovery should be as long as required to guarantee patient safety after discharge home.

- -

Patient should always wear a surgical mask during recovery and discharge.

- -

If the patient is discharged home, both they and their carer must be given printed instructions and self-care recommendations.

- -

All patients should be followed up on the eHealth portal, unless they present procedure- or analgesia- related complications or side effects.

- -

- •

Outpatient procedures in the surgical suite:

- -

Preoperative considerations:

- o

Patients should be screened by telephone 24 h before the intervention to determine their current health status and to explain the organisational aspects of the procedure: arrival, accompanying carer, discharge from the centre after the intervention.

- o

Patients and their carers, as applicable, must wear a surgical mask on arrival at the area.

- o

Only 1 carer, who must be asymptomatic, should be allowed per patient. Carers with fever or symptoms will not admitted.

- o

Carers should wait in rooms, equipped with a hand sanitizer, that are large enough to follow the 2 m safety rule. If this is not possible, the carer must be allowed to wait in their vehicle, notifying them by phone when it is time for them to collect the patient.

- o

When the patient arrives in the surgical suite, make a note their medical history, allergies and other routine information in their clinical record.

- o

Tell the patient that an airway examination will not be performed, and explain why.

- o

The patient, or a member of their family if they are in isolation, must sign an informed consent form. A digital document that can be signed directly on an electronic device should be used, whenever possible.

- o

Check the report of the preoperative workup, if available.

- o

- -

Intraoperative considerations:

- o

There must be enough space in the surgical suite to don and doff PPE safely.

- o

The most experienced practitioner should perform the procedures.

- o

The operating room doors must remain hermetically sealed during the intervention. Only essential personnel wearing full PPE: FFP2/FFP3 masks (particularly in aerosol-generating procedures), goggles or face shield, waterproof gown and double gloves, should remain inside in operating room.

- o

All equipment (radiofrequency needles, fluoroscope, etc.) and infusion sets or syringes must be prepared before starting the procedure in order to minimise the need for opening and handling trolleys. Use disposable material whenever possible. Likewise, any medication that will or might be required must be prepared and placed on a large tray in order to minimise the need to open drug carts. Anything that may be needed for the procedure must be available inside the operating room to avoid the need to open the doors after the patient has arrived.

- o

A runner nurse may be placed outside the doors to fetch anything that is not already available in the COVID operating room.

- o

Monitoring should be tailored to the patient's status and the analgesic technique to be performed. The standard techniques recommended by the ASA and SEDAR (continuous ECG, NIBP, SatO2) should be used.

- o

Non-opioid drugs such as paracetamol or NSAIDs should be used for postoperative pain control.

- o

Sedation should be performed with appropriately titrated, short-acting, intravenous drugs (propofol, remifentanil).

- o

Intraoperative oxygen therapy in awake patients should preferably be performed with low flow nasal cannulas with the patient wearing a surgical mask. High flow oxygen and Venturi masks or non-invasive ventilation should be avoided, as they can cause aerosolization. Hui et al.9 showed that dispersion of particles exhaled by the patient increases in direct proportion to the increase in oxygen flow (distances of 0.2, 0.22, 0.3 and 0.4 m during the administration of 4, 6, 8 and 10 l/min, respectively).

- o

If point-of-care devices such as ultrasound or fluoroscopes are used, the main unit and cable must be encased in plastic to minimise equipment contamination.

- o

- -

Postoperative considerations:

- o

Patients should recover in the operating room itself (avoid moving them to another unit). Postoperative recovery should take as long as required to guarantee patient safety after discharge home.

- o

Patients should always wear a surgical mask during recovery and discharge.

- o

If the patient is discharged home, both they and their carer must be given printed instructions and self-care recommendations.

- o

All patients should be followed up on the eHealth portal, unless they present procedure- or analgesia- related complications or side effects.

- o

Triage for interventional procedures to treat chronic pain in the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Order of importance | Type of procedure | Decision |

|---|---|---|

| Emergent | • Complications in any patient with any recent implant (e.g. infection or wound dehiscence) | Proceed, do not postpone |

| • Phase 2 implantation of spinal, peripheral or dorsal root ganglion neurostimulator with external leads | ||

| • Blood patch to control post-dural puncture headache or intracranial hypotension | ||

| • Migration of existing electrodes that causes neurological deficits or severe pain | ||

| • Intrathecal pump refill or malfunction | ||

| • Epidural or paravertebral catheter for rib fractures | ||

| Urgent (can be individualized) | • Neurolytic procedures for refractory cancer-related pain | Consider and evaluate the risks and benefits with the patient and the service. May proceed after assessment if resources are available |

| • Epidural steroid injections for acute herniated disc or breakthrough pain | ||

| • Vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty for management of refractory pain secondary to acute vertebral compression fracture | ||

| • Replacement of neurostimulation device if sudden discontinuation of therapy will probably lead to decompensation | ||

| • Sympathetic nerve block for acute complex regional pain syndrome refractory to conservative treatment | ||

| • Treatments for acute exacerbation or refractory exacerbation of spinal pain if there is a high probability of physical or psychological disability (radiofrequency ablation in a patient with disabling recurrence after prior relief, sacroiliac joint injection for acute and disabling pain) | ||

| • Nerve entrapment syndromes with neurological deficits | ||

| • Acute headaches likely to respond to nerve blocks (e.g., occipital neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia) | ||

| Scheduled | • Epidural steroid injections for chronic pain | Postpone or cancel |

| • Selective nerve root blockade | ||

| • Diagnostic medial bundle branch block, most intra-articular facet blocks, and repeat preventive radiofrequency denervation for chronic pain | ||

| • Trigger point injections | ||

| • Diagnostic discography | ||

| • Peripheral or intra-articular joint injections (hip, knee, etc.) | ||

| • Neuromodulation (conventional spinal cord stimulation or peripheral nerve stimulation) | ||

| • Ketamine and other intravenous drugs | ||

The possibility of prescribing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics (NSAIDs) is still under debate. Case reports of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 who appeared to show clinical deterioration after taking ibuprofen has raised concerns among clinicians and patients about the safety of NSAIDs during the COVID-19 pandemic. The association between NSAIDs and increased angiotensin levels appears to increase susceptibility to infection or aggravate symptoms. Currently, neither the FDA nor the European Medicines Agency are aware of any evidence linking the use of any NSAIDs with COVID-19 infection10,11. Therefore, it seems reasonable that patients who were taking NSAIDs on a long-term basis before the pandemic can continue to do so, and that patients with newly diagnosed acute or chronic pain can start treatment with NSAIDs. NSAIDs, however, being anti-inflammatory agents, can mask the early symptoms of the disease, such as fever and myalgia, and should always be used with caution and close monitoring in elderly patients and in those with cardiovascular or kidney disease, in whom low-dose, short courses are recommended12,13. In any event, although NSAIDs are not officially contraindicated in COVID-10, patients with pain should immediately report any possible symptoms of COVID-19 (mild fever or myalgia) or recent high-risk exposure to the disease so that they can be switched to paracetamol, a drug recommended by the World Health Organization for use as an analgesic and antipyretic during the COVID-19 pandemic14,15.

Recommendations for the use of opioids during the COVID-19 pandemicOpioids are the most effective treatment for acute and chronic pain, and have been shown to be effective in neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain16,17. Although opioid critics point to the lack of quality evidence to show any benefit for more than 3 months, systematic reviews have shown that they can improve long-term quality of life in patients with severe chronic pain18,19.

COVID-19-related morbidity and complications are more common in the elderly and immunocompromised patients, a fact that highlights the importance of the immune response in avoiding infection and minimizing fatalities. The effect of opioids on the immune system is complex and depends on the type of opioid used, the dose, the nature of the immunity (opioids have different effects on different immune cells) and the clinical context20. Chronic opioid therapy has been linked to infection21. Pain itself, however, may have an immunosuppressive effect, so using opioids to relieve acute pain may actually enhance the immune response22.

Taking all these factors into consideration, eHealth portals can be used to prescribe provisional short courses of opioids in all patients taking non-opioid drugs and presenting break-through pain. In these cases, patients should be contacted after 1 or 2 weeks. If they still need opioids, they should attend a monthly in-person medical consultation to perform a physical examination to assess the severity of the pathology or its progression, confirm the symptoms, monitor the non-organic signs, detect possible red flags, and identify patients that are candidates for interventional procedures.

Patients who are already taking opioids can receive a temporary dose increase, but should be scheduled for a face-to-face visit within 2 months of dose escalation to assess possible progression of the underlying disease, opioid tolerance, opioid hyperalgesia, and use of opioids to treat painless conditions that could benefit from other treatments, such as psychotherapy.

In patients with intrathecal drug infusion devices, drug refills are considered priority procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic, and will be managed according to the recommendations provided in these guidelines.

Patients with transdermal opioids presenting active infection should be carefully monitored, because high fever can alter the rate of absorption.

Recommendations for the use of steroids during the COVID-19 pandemicSteroids are known to suppress the immune system, and systemic steroids have been linked to infections, including pneumonia23. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression usually lasts less than 3 weeks, but may last more than 1 month in some individuals24,25. Dexamethasone and betamethasone appear to reduce this type of immunosuppression26. All this suggests that procedures that involve the administration of steroids may increase the risk of infection and, therefore, should be prescribed with caution, particularly in immunocompromised patients who may be at increased risk of infection during the corticosteroid-associated immune suppression window.

It is also important to consider dosage. Randomized trials have evaluated different doses of steroids administered by various routes, and for the most part have found that the doses typically used in clinical practice are too high27.

The Spine Interventional Society has shown that there is no clear evidence of a causal effect between spinal steroid injections and periprocedural infection in immunosuppressed patients28. Based on this recommendation and the foregoing information, we believe that neuraxial procedures involving corticosteroids can continue to be performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, provided the risk/benefit ratio is evaluated in each case, the lowest possible dose is administered, and patients are informed of the possibility of immunosuppression and potential risk of infection. In immunosuppressed patients that are, consequently, at high risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection, steroid injections can be ruled out, except in cases of severe radicular pain refractory to other measures. Even in these cases, the benefit of steroid therapy must always be weighed up against the potential risk of infection7.

Psychological monitoring of patients with chronic pain during the COVID-19 pandemicThe mental health problems associated with the COVID-19 pandemic include mainly psychiatric symptoms (depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, insomnia) related to confinement and quarantine: fear of infection, frustration and boredom, poor housing, shortage of food and hygiene supplies, access to information, financial losses, and social stigma29.

These mental health considerations are very important, because mental health problems are common in patients with chronic pain30. Mental health issues associated with the COVID-19 pandemic could exacerbate these pre-existing conditions, and this, in turn, could negatively affect pain management outcomes31,32.

A survey conducted in China between 31 January and 8 February 2020 provided important preliminary data on the impact of COVID-19 on the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms. The psychological impact of the pandemic was rated as moderate to severe by 53.8% of respondents, 16.5 to 28.8% reported moderate to severe symptoms of depression and anxiety, while 8.1% reported moderate to severe levels of stress33.

All this supports the need for psychological monitoring in patients with chronic pain during health crises.

ConclusionsManagement of chronic pain has not traditionally been considered important in times of crisis, including epidemics. However, the right of patients to well-being, social benefits and the public health standards inherent to pain management, as well as the responsibility of healthcare providers and caregivers to provide comprehensive care, including adequate analgesia, have highlighted the importance of chronic pain management.

The health system has a duty of care for patients with chronic pain due to the serious physical, psychological and social repercussions of neglecting their needs in any context. This includes the current pandemic, in which, despite the need to reorganise resources, healthcare providers must still guarantee that patients receive appropriate follow-up.

FundingThis manuscript has not received any funding.

Conflict of interestsNo conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Asensio-Samper JM, Quesada-Carrascosa M, Fabregat-Cid G, López-Alarcón MD, de Andrés J. Recomendaciones prácticas para el manejo del paciente con dolor crónico durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2021;68:495–503.