To review the complications associated with the minimally invasive retropleural approach used in the anterior approach to the thoraco-lumbar spine.

Material and methodWe present the MIS surgical technique and the evaluation of data collected prospectively from the initial series of 31 patients undergoing surgery. Pleural opening during the approach, lung complications derived, other surgical complications, time of intervention, intraoperative bleeding, need for transfusion and hospital stay are evaluated.

DiscussionThe mean age of the patients was 58 years, the surgical time 225min, and the bleeding 274ml, with a 13% postoperative transfusion. Intraoperatively, pleural opening was detected in 8 cases, of which none had major pulmonary complications during the postoperative period. There were 3 cases of mild pleural effusion, all patients without pleural opening, and one case of haemopneumothorax due to intercostal vessel bleeding that required reoperation. The percentage of intercostal neuralgia was 3%. The mean hospital stay was 6.7 days, and 24 of 31 patients were able to initiate early mobilization on the first postoperative day.

ConclusionsThe retropleural approach allows the surgical treatment of pathologies requiring anterior access to the thoraco-lumbar spine, with a low profile of pulmonary complications, and with the advantages of minimally invasive techniques in terms of less bleeding, early recovery and shorter hospital stay. Nevertheless the learning curve is long.

Revisar las complicaciones asociadas al abordaje retropleural mínimamente invasivo utilizado en el abordaje anterior a la columna toracolumbar.

Material y métodoSe presenta la técnica quirúrgica y la evaluación de datos recogidos de manera prospectiva de la serie inicial de 31 pacientes intervenidos. Se evalúa la apertura de pleura durante el abordaje, las complicaciones pulmonares derivadas, otras complicaciones quirúrgicas, el tiempo de intervención, el sangrado intraoperatorio, la necesidad de transfusión y la estancia hospitalaria.

ResultadosLa edad media de los pacientes fue de 58años, el tiempo quirúrgico de 225min y el sangrado de 274ml, con un 13% de transfusión en el postoperatorio. De forma intraoperatoria se detectó la apertura de la pleura en 8casos, de los cuales ninguno tuvo complicaciones mayores pulmonares durante el postoperatorio. Se produjeron 3 casos de derrame pleural leve en pacientes sin apertura de pleura, y un caso de hemoneumotórax por sangrado de vaso intercostal que requirió reintervención. El porcentaje de neuralgia intercostal fue del 3%. La estancia media hospitalaria fue de 6,7días, y 24 de 31 pacientes pudieron iniciar movilización precoz el primer día postoperatorio.

ConclusionesEl abordaje retropleural permite el tratamiento quirúrgico de patologías que requieren un acceso anterior a la columna toracolumbar, con un perfil bajo de complicaciones pulmonares y con las ventajas de las técnicas mínimamente invasivas en cuanto a menor sangrado, recuperación precoz y menos estancia hospitalaria. Su curva de aprendizaje es larga.

The anterior approach to the thoraco-lumbar segment enables reconstruction of the anterior wall in cases of vertebral fracture, metastasis and inflammatory injuries.1,2 It is also used for decompression of the medullary canal and correction of deformities in cases where the posterior approach alone would not be sufficient.3–7

The percentage of complications associated with the classical approach using thoracotomy in the literature is found to be around 40%–50%,3,5,8 with specifically pulmonary complications accounting for up to 64% in some series.9

With the boom of minimally invasive techniques (MIS) as alternatives to standard approaches, thorascopy has acquired a major significance, due to the reduction of morbidity in contrast to the extensive incision-dissection used in thoracotomy. The thorascopic approach is associated with lower bleeding, less postoperative pain and early post surgical recovery.1,10,11 However, it is still a transthoracic approach, with possible associated pulmonary complications because the approach thresholds invade the pleural cavity.1,10

The first retropleural approach was described by McCormick12 in the 1990s for observation of the anterolateral spine without the need to enter the pleural cavity and therefore in theory, reducing pulmonary morbidity associated with thoracotomy. The retropleural approach in its minimally invasive mode combines the advantages of the MIS techniques (regarding bleeding, early recovery, hospital stay time…) with fewer pulmonary complications and the preservation of the pleura intact.2,3,6,7 Its use is not extensive, as shown by the low quantity of publications in recent years.

The aim of this study is to review the complications associated with the minimally invasive retropleural approach in patients who underwent surgery in our hospital, with particular emphasis on pulmonary complications, to assess the safety of this surgical technique.

Material and methodBetween January 2012 and June 2016, 31 patients underwent surgery in our hospital with the MIS retropleural approach. Prospective recording in all patients was made of time in surgery; intraoperative bleeding; pleural opening during the approach and other intraoperative complications. During hospitalization the following were recorded: pulmonary complications; non pulmonary complications; the need for transfusion and hospital stay. During follow-up the following were recorded: complications and the need for further surgery due to causes relating to the approach. The patients were reviewed in external surgeries after 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, one year and 2 years.

A retrospective review of data obtained prospectively was carried out.

Description of the surgical techniqueSurgery was performed under general anaesthesia with selective pulmonary intubation for posterior lung collapse, if required. Generally a left-sided approach was preferred as vascular status was more favourable, close to the aorta instead of the azygos venous system. The left-sided approach also allows for better mobilization of the diaphragm, which is hindered by the liver in a right-sided approach. For the left-sided approach the patient is in right lateral decubitus position. The correct lateral position of the patient's spine must be confirmed under scopic observation since in the case of obliquity there is an increased risk of invading the medullary canal or causing damage to the large blood vessels when manipulating the disc and the vertebral body.

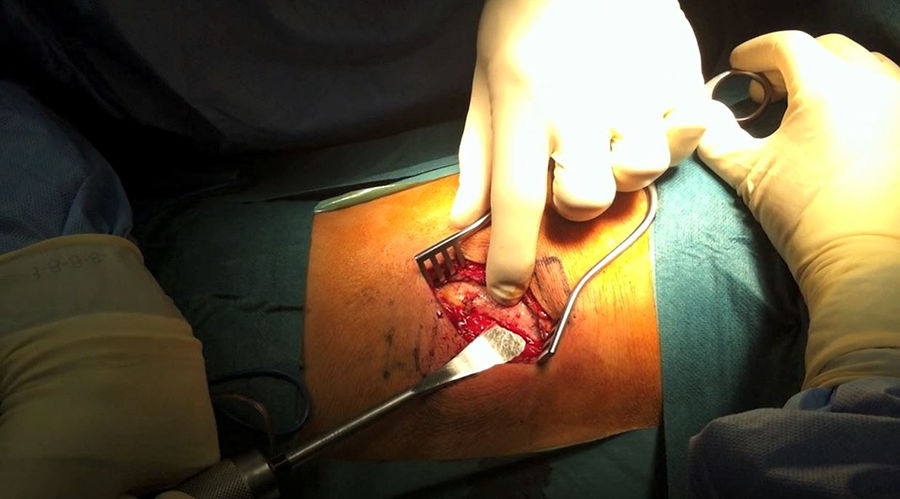

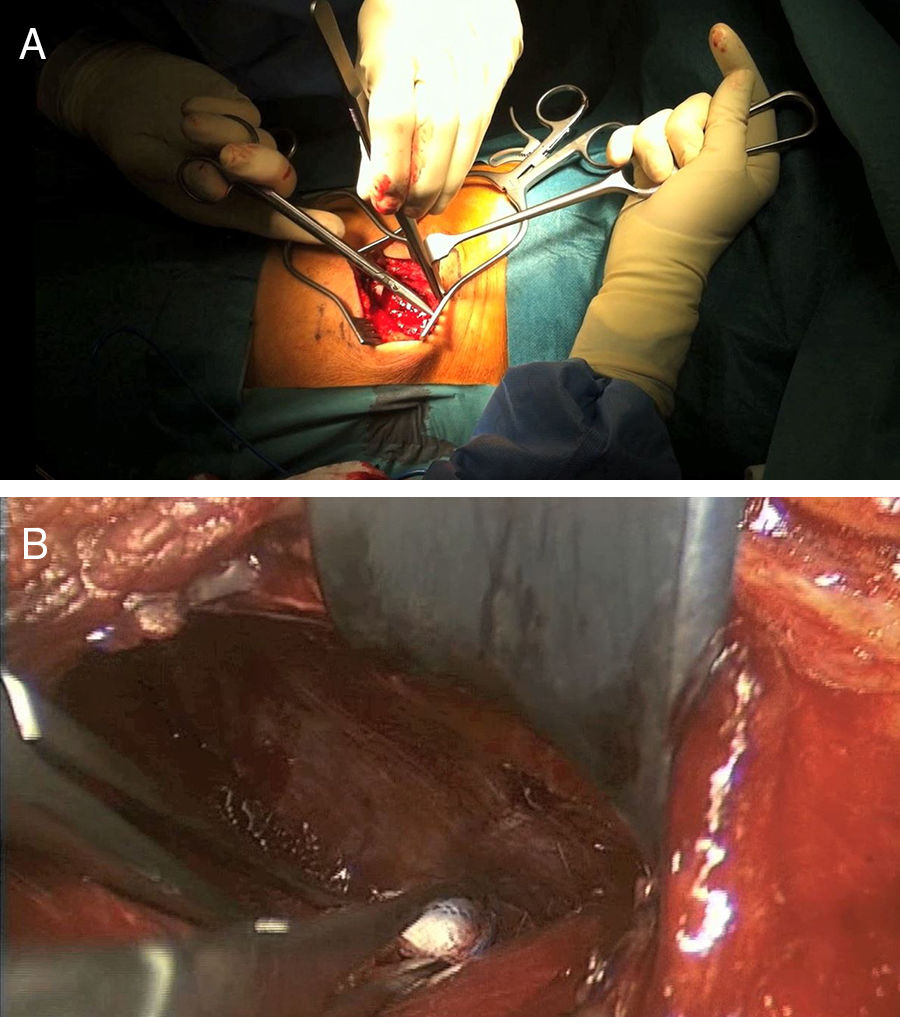

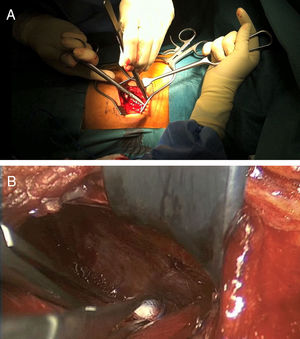

After identifying skin level and marking with scopic assistance, an incision of 5–7cm was made on the disc to be approached by following the direction of the rib. The underlying muscle mass was separated and the rib was carefully detached from the periosteum so as not to damage the vessel bundle, with the periosteum continuing to be attached to the pleura (Fig. 1). Osteotomy of the rib was then performed, resecting a fragment of 4–5cm. Retropleural dissection was performed generally with the lung collapsed, patient characteristics permitting. If not, this is not necessary. This facilitates dissection of the soft tissues and separation from the parietal pleura of the endothoracic fascia from the posterior region of the costal osteotomy to the thoracic spine (Fig. 2).

To create space to access the disc and the vertebral bodies, the parietal pleura was separated from the lung using a pneumatic separator with valves anchored to the operating table (Unitrac®, Aesculap B-Braun). The spine was accessed at thoraco-lumbar level between the fibres of the psoas muscle separating the diaphragm inferiorally and at times the diaphragm cross should be slightly divided if we wished to extend the approach to further inferior levels (L1–L2).

With this approach bipolar forceps may be used to coagulate the segmental arteries if required in the case of corpectomy. A surgical microscope may also be used and implants may be inserted as a replacement for the vertebral body or screwed plates, without the need to extend the incision.

Following surgery, the separator must be carefully removed so as to avoid damaging the pleura. Physiological serum is used to confirm that there are no leakages and a drain is inserted.

If pleural opening is observed a thoracic tube for pleural drainage is inserted which is removed after 48h if the control chest X-ray is appropriate. Should a minimal opening appear or the opening may not be sutured, only a drain is inserted.

During the post-operative period the patient is encouraged to start sitting and walking on the first day if the saturation is correct, and respiratory physiotherapy is recommended during their hospital stay. A control chest X-ray is recommended the day after surgery and prior to hospital discharge.

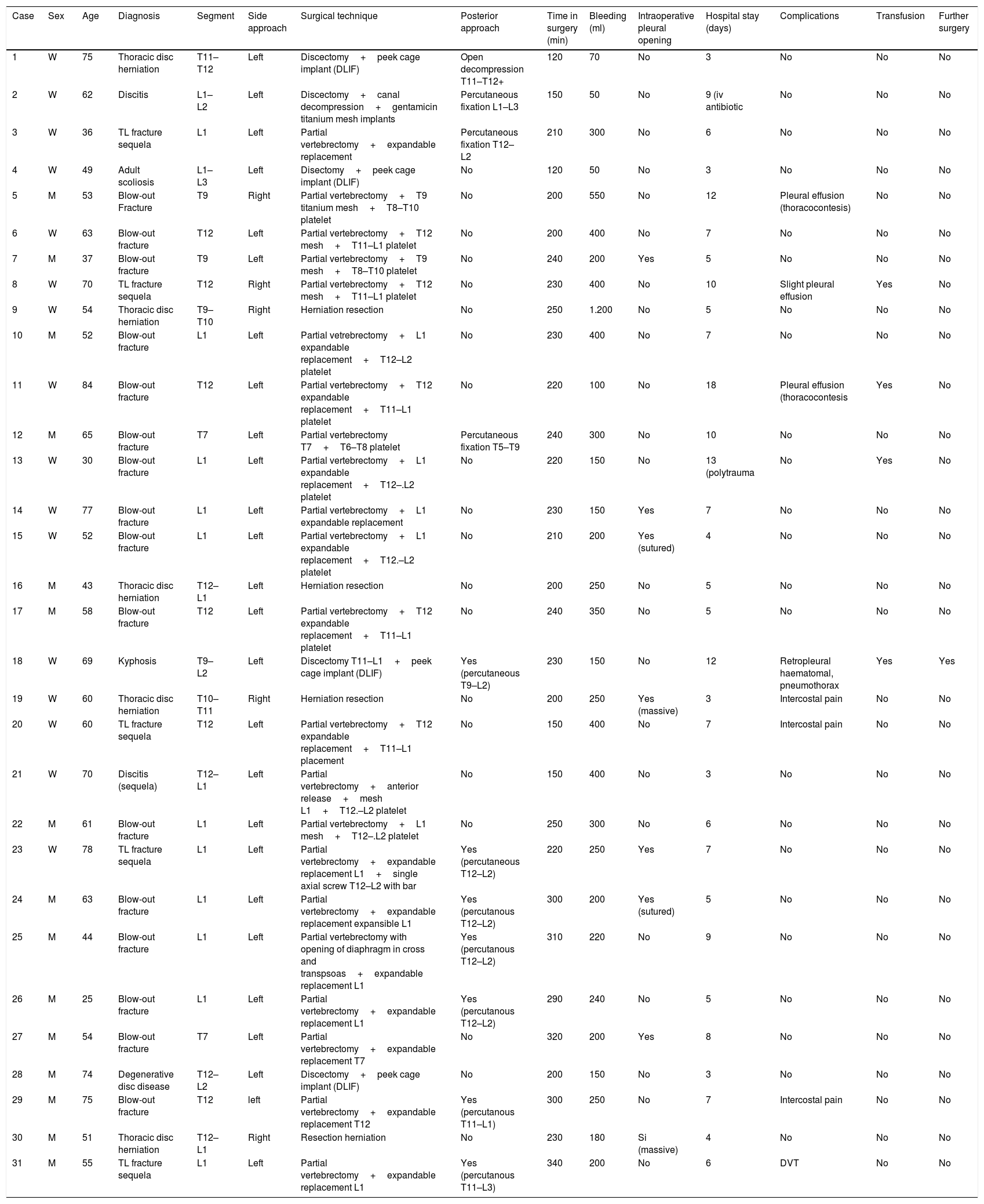

ResultsBetween January 2012 and June 2016, 31 patients – 16 women and 15 men – underwent surgery in our hospital with a MIS retropleural approach. Their mean age was 58 [25–84] years. In 5 patients resection of thoracic herniation was performed, in 16 patients fixation of thoraco-lumbar fracture, in 5 patients correction of kyphosis after thoracic fracture sequela, in 3 patients intersomatic cages were implanted for the correction of degenerative deformities, and in 2 cases treatment for discitis was performed. Table 1 contains the different techniques employed.

Techniques used.

| Case | Sex | Age | Diagnosis | Segment | Side approach | Surgical technique | Posterior approach | Time in surgery (min) | Bleeding (ml) | Intraoperative pleural opening | Hospital stay (days) | Complications | Transfusion | Further surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | W | 75 | Thoracic disc herniation | T11–T12 | Left | Discectomy+peek cage implant (DLIF) | Open decompression T11–T12+ | 120 | 70 | No | 3 | No | No | No |

| 2 | W | 62 | Discitis | L1–L2 | Left | Discectomy+canal decompression+gentamicin titanium mesh implants | Percutaneous fixation L1–L3 | 150 | 50 | No | 9 (iv antibiotic | No | No | No |

| 3 | W | 36 | TL fracture sequela | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+expandable replacement | Percutaneous fixation T12–L2 | 210 | 300 | No | 6 | No | No | No |

| 4 | W | 49 | Adult scoliosis | L1–L3 | Left | Disectomy+peek cage implant (DLIF) | No | 120 | 50 | No | 3 | No | No | No |

| 5 | M | 53 | Blow-out Fracture | T9 | Right | Partial vertebrectomy+T9 titanium mesh+T8–T10 platelet | No | 200 | 550 | No | 12 | Pleural effusion (thoracocontesis) | No | No |

| 6 | W | 63 | Blow-out fracture | T12 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+T12 mesh+T11–L1 platelet | No | 200 | 400 | No | 7 | No | No | No |

| 7 | M | 37 | Blow-out fracture | T9 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+T9 mesh+T8–T10 platelet | No | 240 | 200 | Yes | 5 | No | No | No |

| 8 | W | 70 | TL fracture sequela | T12 | Right | Partial vertebrectomy+T12 mesh+T11–L1 platelet | No | 230 | 400 | No | 10 | Slight pleural effusion | Yes | No |

| 9 | W | 54 | Thoracic disc herniation | T9–T10 | Right | Herniation resection | No | 250 | 1.200 | No | 5 | No | No | No |

| 10 | M | 52 | Blow-out fracture | L1 | Left | Partial vetrebrectomy+L1 expandable replacement+T12–L2 platelet | No | 230 | 400 | No | 7 | No | No | No |

| 11 | W | 84 | Blow-out fracture | T12 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+T12 expandable replacement+T11–L1 platelet | No | 220 | 100 | No | 18 | Pleural effusion (thoracocontesis | Yes | No |

| 12 | M | 65 | Blow-out fracture | T7 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy T7+T6–T8 platelet | Percutaneous fixation T5–T9 | 240 | 300 | No | 10 | No | No | No |

| 13 | W | 30 | Blow-out fracture | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+L1 expandable replacement+T12–.L2 platelet | No | 220 | 150 | No | 13 (polytrauma | No | Yes | No |

| 14 | W | 77 | Blow-out fracture | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+L1 expandable replacement | No | 230 | 150 | Yes | 7 | No | No | No |

| 15 | W | 52 | Blow-out fracture | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+L1 expandable replacement+T12.–L2 platelet | No | 210 | 200 | Yes (sutured) | 4 | No | No | No |

| 16 | M | 43 | Thoracic disc herniation | T12–L1 | Left | Herniation resection | No | 200 | 250 | No | 5 | No | No | No |

| 17 | M | 58 | Blow-out fracture | T12 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+T12 expandable replacement+T11–L1 platelet | No | 240 | 350 | No | 5 | No | No | No |

| 18 | W | 69 | Kyphosis | T9–L2 | Left | Discectomy T11–L1+peek cage implant (DLIF) | Yes (percutaneous T9–L2) | 230 | 150 | No | 12 | Retropleural haematomal, pneumothorax | Yes | Yes |

| 19 | W | 60 | Thoracic disc herniation | T10–T11 | Right | Herniation resection | No | 200 | 250 | Yes (massive) | 3 | Intercostal pain | No | No |

| 20 | W | 60 | TL fracture sequela | T12 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+T12 expandable replacement+T11–L1 placement | No | 150 | 400 | No | 7 | Intercostal pain | No | No |

| 21 | W | 70 | Discitis (sequela) | T12–L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+anterior release+mesh L1+T12.–L2 platelet | No | 150 | 400 | No | 3 | No | No | No |

| 22 | M | 61 | Blow-out fracture | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+L1 mesh+T12–.L2 platelet | No | 250 | 300 | No | 6 | No | No | No |

| 23 | W | 78 | TL fracture sequela | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+expandable replacement L1+single axial screw T12–L2 with bar | Yes (percutaneous T12–L2) | 220 | 250 | Yes | 7 | No | No | No |

| 24 | M | 63 | Blow-out fracture | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+expandable replacement expansible L1 | Yes (percutanous T12–L2) | 300 | 200 | Yes (sutured) | 5 | No | No | No |

| 25 | M | 44 | Blow-out fracture | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy with opening of diaphragm in cross and transpsoas+expandable replacement L1 | Yes (percutanous T12–L2) | 310 | 220 | No | 9 | No | No | No |

| 26 | M | 25 | Blow-out fracture | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+expandable replacement L1 | Yes (percutanous T12–L2) | 290 | 240 | No | 5 | No | No | No |

| 27 | M | 54 | Blow-out fracture | T7 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+expandable replacement T7 | No | 320 | 200 | Yes | 8 | No | No | No |

| 28 | M | 74 | Degenerative disc disease | T12–L2 | Left | Discectomy+peek cage implant (DLIF) | No | 200 | 150 | No | 3 | No | No | No |

| 29 | M | 75 | Blow-out fracture | T12 | left | Partial vertebrectomy+expandable replacement T12 | Yes (percutanous T11–L1) | 300 | 250 | No | 7 | Intercostal pain | No | No |

| 30 | M | 51 | Thoracic disc herniation | T12–L1 | Right | Resection herniation | No | 230 | 180 | Si (massive) | 4 | No | No | No |

| 31 | M | 55 | TL fracture sequela | L1 | Left | Partial vertebrectomy+expandable replacement L1 | Yes (percutanous T11–L3) | 340 | 200 | No | 6 | DVT | No | No |

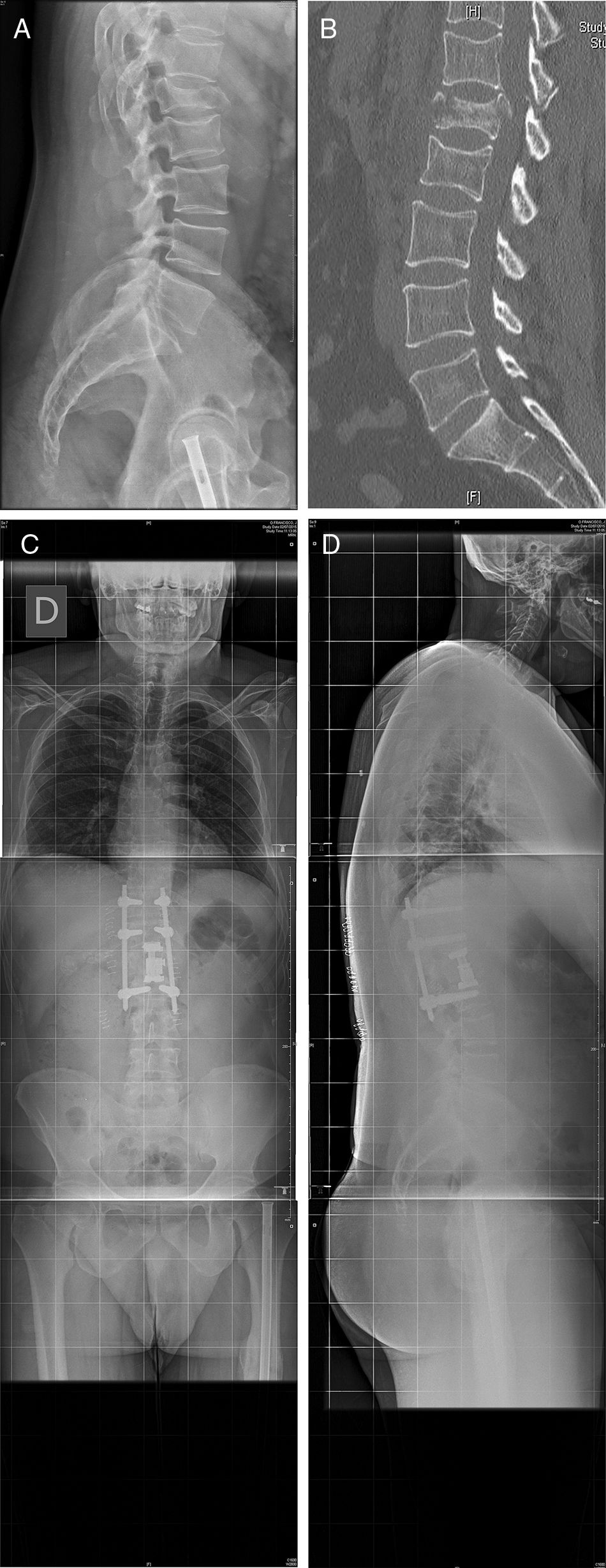

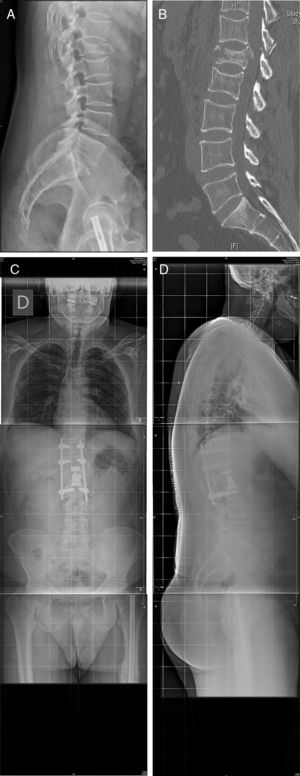

Twenty six approaches were left-sided and 5 were right-sided due to the requirements of the pathology involved. Mean time in surgery was 225 [120–340]min, and mean intraoperative bleeding was 274 [50–1.200]ml. Fig. 3 illustrates one of the cases (case 25).

Case 25: Blow-out fracture L1 in polytraumatised patient in a traffic accident (A). The TC (B) is compromised in the posterior wall and there is comminution. We therefore decided to perform surgery with a double approach: retropleural corpectomy and the insertion of a vertebral replacement, with posterior fixation using percutaneous screws (C, D). No pleural opening took place during surgery and there were no complications during the postoperative and follow-up periods.

In 8 cases an opening of the pleura occurred during the approach. In 2 patients the pleura was sutured, in the other 6 cases a thoracic draining tube was inserted which was removed after 48h. As a result, 24 patients were able to initiate early mobilization one day after surgery because they did not require pleural drainage.

No major pulmonary complications associated with pleural opening during the postoperative period were recorded (atelectasis, pneumonía, pleural effusion, pneumothorax…). No other intraoperative complications were recorded (large blood vessel injuries, medular-radicular injury ….) and in no case did surgery have to be converted from minimally invasive to an open surgery technique.

In the immediate postoperative period only 4 of the 31 patients (13%) required a transfusion of 2 packed red blood cells.

In the control X-ray after 24h in 3 of the cases without intraoperative opening of the pleura a minimal effusion in the thoracic cavity was detected: in one case the patient was asymptomatic and this was interpreted as reactive pleuritis and was resolved spontaneously without the need for thoracocentesis prior to hospital discharge. In the other two cases the effusion caused mild dyspnoea which improved after thoracocentesis of the serohaematic fluid.

The most notable pulmonary complications in our series was a case of retropleural haematoma caused by bleeding of the intercostal bundle and complicated with a pneumothorax and severe dysnoea which required surgical review on the second postoperative day, with drainage of the haematoma, ligature of the bleeding vessel and the insertion of an endothoracic tube. The patient evolved favourably and was discharged 6 days after surgery when a chest X-ray was normal.

The only major non pulmonary surgical complication in the series was a case of DVT and there were 3 cases of minor complications of intercostal pain, which improved with anti-inflammatory treatment. Mean hospital stay was 6.7 days.

No complications were detected during follow-up in the doctor's surgery nor did any of the patients receive further surgical treatment for complications relating to this surgical approach.

DiscussionIn this first series of 31 cases we confirmed that the minimally invasive retropleural approach provides good vision of the anterolateral spine, using a similar working angle to the mini-thoracotomy and this allows for the segmental arteries to be ligated in the case of vertebrectomy, expanding up to L1–L2 when necessary, using light de-insertion of the diaphragm. Furthermore, unlike thorascopy implants may be inserted through the same incision and this allows for the use of surgical microscopy with observation of the surgical field increased three-dimensionally. As a result of all of these technical reasons this approach may now be used for the treatment of multiple pathologies, such as thoracic herniation resection, the treatment of thoraco-lumbar fractures, degenerative pathologies, treatment of infections and tumours and correction of deformities.2,6,7,13,14 The main advantage associated with the retropleural approach is that it does not invade the pleural space, and the percentage of postoperative pulmonary complications is therefore lower.1,3,4,6,12

In our series the only recorded intraoperative complications was the opening of the pleura during surgery, which occurred in 8 cases, out of which none led to complications during the postoperative and follow-up period. The pulmonary complications described occurred in patients without pleural opening during the approach, although in the two symptomatic cases which required thoracocentesis the effusion could have been related to the unnoticed opening of the pleura intraoperatively. There were no postoperative cases of pneumonia or atelectasis, and the percentage of pulmonary complications in our series was 6.5%.

The general percentage of pulmonary complications described in the MIS published series is low, similar to our series. In a series of 38 patients, who mostly underwent surgery for tumours, Scheufler6 refers to 11 sutured pleural openings, and only in 2 cases was postoperative endothoracic tubing required, one due to the pleural opening and the other due to the postsurgical pleural effusion. He refers also to 2 cases of postoperative atelectasis. Moran et al. Recorded 5 suturable pleural openings during the approach in the treatment of 17 cases of giant thoracic herniation, with the need for endothoracic tubes in one case.3 Baaj et al.,2 in their series of 80 cases, published a global rate of complications of 12.5%, with specifically pulmonary complications being 3% of the total, with one case of haemothorax and another of pleural effusion.

One of the minor complications described in anterior approaches is intercostal neuralgia. The MIS retropleural approach requires minimal costal resection and it is also possible to perform it with intercostal entry with dilators, where there is a lower risk of intercostal nerve damage and therefore a lower rate of postoperative intercostal neuralgia compared with thoracotomy.3,4,6,13,14 In our series there were only 3 cases of intercostal neuralgia which was relieved in under one month with NSAIDs s (3%), a percentage that is similar to other published series, with only one or two cases.2,6,7

No other major intraoperative complications were recorded (large blood vessel damage, dural opening, medullary radicular damage …). There was only one case of DVT immediately after surgery. In no case did the surgery have to be converted from minimally invasive to an open technique and there was only one case of surgical revision, which has been described above.

The major complication most frequently described in the literature is the opening of the dura mater to the thoracic cavity,3,6 with the technical difficulty required for repair of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fistula in these cases. We were unable to confirm the theoretical advantage of not opening the pleura since we did not record dura mater injury in any cases, but we agree that if the pleura is to remain whole, dealing with CSF fistulas in the thoracic cavity, should they arise, is technically simpler.

In our series mean intraoperative bleeding was 274ml, with a low rate of transfusion (13%). If bleeding was higher than expected (1.200ml) this was due to the comorbidities of the patient Scheufler6 estimates mean bleeding of 280ml and Patel et al.7 of 200ml. Our series is therefore within the range published up until now.

Hospital stay was 6.7 days in our series. In the series by Patel et al.,7 which only includes degenerative pathologies, hospital stay was 4days. The increase in hospital stay in our series was possibly due to the fact that the majority of cases underwent surgery for thoraco-lumbar fractures and correction of deformities. Low hospital stay was possible because not all cases required a thorax tube after surgery, and this allowed for the patient to rapidly start moving, leading to early postoperative recovery.1,3,12

In our series the mean time in surgery was 225min. Due to the scarcity of publications in this regard it is difficult for us to compare this aspect. Scheufler6 published a mean time in surgery of 163min, whilst Uribe et al.,4 with only 4 cases, published a mean time of 300min. This surgical technique is demanding and has a long learning curve. In our case we presented the first 31 patients who underwent this type of surgery in our hospital, and it is therefore probable that the time in surgery would be lower in the future, as would the number of cases of intraoperative pleural opening.

Among the limitations for this study are a short series of cases where a retrospective review of data acquired prospectively was made, without a control group or comparison with other series where thoracotomy or thoracoscopy was used. Since this was an initial series different diagnoses and techniques were mixed together, which would definitely have had an influence on bleeding and time in surgery. Our current objective was to assess the pulmonary complications associated with the approach and assess their safety profile. A comparative study between pathologies is therefore necessary when future larger patient series are used. Despite the before-mentioned limitations, no article has yet been published which specifically assesses pulmonary complications relating to the advantage of the retropleural approach in maintaining the pleura intact.

ConclusionThe retropleural approach facilitates observation of the anterolateral spine and the performing of corpectomy and decompression of the medullary canal, with a lower general rate of complications compared with the open transthoracic approach. The rate of complications is comparable to thoracoscopic techniques, with the advantage of increased three-dimensional vision using a microscope, and the possibility of inserting implants without the need for additional incision. Bleeding and hospital stay is lower because this is a minimally invasive technique. It does, however, require a long learning curve.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence 4.

Please cite this article as: Bordon G, Burguet Girona S. Evaluación crítica de las complicaciones asociadas al abordaje retropleural mínimamente invasivo en cirugía de columna toracolumbar. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:209–216.