Determine the complications related to the different techniques for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients under 18 years old.

MethodologySystematic review using the databases Medline, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Embase (until July 2016), additional studies were included conducting a search of the references of previous studies. The terms included in the search were: “cruciate”, “ligament”, “anterior”, “immature”, “complications”, “outcome”, “acl reconstruction”, “cruciate ligament anterior reconstruction”, “children”, “child”, “infants”, “adolescent”, “open physis”, “growth plate” and “skeletally immature”.

ResultsA number of 73 studies were included; 1300 patients in total, average age 13 years, 70% were male, medial and lateral meniscal lesions in 26% and 30% respectively. Eleven cases of length discrepancy (0.8%): 4 cases were presented with physeal-sparing techniques (1.4%), 3 cases with partial physeal-sparing techniques (2.2%) and 4 cases were presented with transphyseal techniques (0.4%). There were 22 cases of axis deviation: 6 cases with physeal-sparing techniques (2%), 3 cases with partial physeal-sparing techniques and 13 cases with transphyseal techniques (1.4%). The use of allograft Achilles tendon allograft and fascia lata was associated with increased length discrepancy and axis deviation (25%). There was no difference according to Tanner.

ConclusionsThe different anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction techniques in patients under 18 years old had low complications related to lower limb growth, arthrofibrosis and review. There was a higher percentage of cases of length discrepancy and axis deviation with physeal-sparing techniques than with the other surgical techniques. The evidence level studies cannot determine causality.

Determinar las complicaciones de las técnicas de reconstrucción de ligamento cruzado anterior en menores de 18 años.

MetodologíaRevisión sistemática usando las bases de datos Medline, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews y Embase (hasta julio de 2016). Se incluyeron estudios adicionales realizando búsqueda en las referencias bibliográficas de estudios previos. Los términos incluidos fueron «cruciate», «ligament», «anterior», «immature», «complications», «outcome», «ACL reconstruction»,«cruciate ligament anterior reconstruction», «children», «child», «infants», «adolescent», «open physis», «growth plate» y «skeletally immature».

ResultadosEstudios incluidos: 73; pacientes: 1.300, con un promedio de edad de 13 años, el 70% eran hombres, con lesiones meniscales mediales en un 26% y laterales en un 30%. Hubo 11 casos de dismetría de longitud (0,8%), de los cuales, 4 se presentaron con las técnicas que respetan la fisis (1,4%), 3 con las técnicas que respetan las fisis parciales (2,2%) y 4 con las técnicas transfisiarias (0,4%). Hubo 22 casos de desviación del eje de la extremidad: 6 con las técnicas que respetan la fisis (2%), 3 con las técnicas que respetan la fisis parcial y 13 con las técnicas transfisiarias (1,4%). El uso de aloinjerto de tendón Aquiles y fascia lata se asoció a mayor presentación de dismetría de longitud y desviación de eje (25%).

ConclusionesLas técnicas quirúrgicas tienen bajas tasas de complicaciones relacionadas con el crecimiento de los miembros inferiores, artrofibrosis y revisión. Hubo un mayor porcentaje de casos de dismetría de longitud y desviación de eje con las técnicas que respetan las físis parciales pero, debido al nivel de evidencia de los estudios, no se puede determinar su relación de causalidad.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are considered rare in skeletally immature patients. However, the incidence has increased in recent years. Dodwell et al. reported an increased incidence in New York from 17 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 1990 to 50 cases per 100,000 in 2009.1 Comstock et al. reported an incidence of 14 cases per 100,000 in players of American football.2

Certain intrinsic and extrinsic factors have been considered risk factors for ACL injury. The extrinsic factors include contact sports (football, basketball, skiing), type of footwear and climatic conditions.2–6

The anatomical conditions include reduced intercondylar groove width, reduced ACL volume, increased posterior femoral and tibial slope, ligament hypermobility, increased Q angle, anterior pelvic slope and femoral anteversion.7–9 There is a higher incidence in females than males by a ratio of 2.9–1, because women have more of the anatomical conditions that predispose to ACL injury.

Luhmann reported an anterior cruciate ligament injury in 29% of patients presenting traumatic joint effusion, while Stanistski et al. reported an injury in 63% of children with haemarthrosis. The incidence of associated meniscal injury is 29%.10,11 Krych et al. reported a cure rate of 74% in all types of meniscal injuries after repair.12

Prevention strategies for ACL injury using neuromuscular training have shown that a reduction of up to 67% can be achieved in the incidence of tear.13

Conservative management of these injuries has been associated with ceasing sporting activities in 50% of cases, with irreparable meniscal and joint cartilage injury observed on MRI and arthroscopy, and the possible development of osteoarthritis.14

Many surgical management techniques have been described. The risk of growth alterations after ACL reconstruction that perforates the physis has not been established. The femoral distal physis and proximal tibial physis provide 60% of the growth of the lower limb. The femoral distal physis provides 70% of femoral length with a growth rate of 10mm/year. The distance between the distal femoral physis and the proximal insertion of the ACL is 3mm, and is constant from birth until bone maturity.15 The proximal tibial physis provides 55% of tibial growth, with a growth rate of 64mm per year. The direction, size and speed that the tunnels are created are factors associated with the magnitude of the injury to the physis.16

The surgical techniques can be divided into extraphyseal, total or partial transphyseal and epiphyseal. The types of graft are classified as allograft or autograft from the hamstrings, patellar tendon, quadriceps tendon and iliotibial band.17

Despite the great variety of surgical treatments, there is no evidence-based algorithm for the management of these injuries in children and adolescents.18

MethodologyStudy populationPatients under the age of 18 years with injury to the cruciate ligament, who underwent surgical reconstruction.

ObjectivesThe main objective of the study was to determine the complications associated with ACL reconstruction in patients under the age of 18 years, particularly growth alterations in the lower limbs, infection and arthrofibrosis rates. The secondary objectives were to determine the functional outcomes of the different surgical techniques and the level of evidence in the current literature on the surgical management of ACL injuries in people under the age of 18.

Eligibility criteriaStudies in patients under 18 years of age reporting complication rates; the studies had to describe the surgical technique used, and the follow-up had to be a minimum of 6 months.

SourcesA search was undertaken of the electronic databases: Medline, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and Embase.

Search methodNo restriction was made as to the initial date, up until July 2016. There was no language restriction. The search was limited to age (under 18 years) and studies on human beings. The following MesH terms (medical subject headings) were used: “anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction”, “humans”, “infant”, “child”, “adolescent”, along with the following keywords (free-text words): “cruciate”, “ligament”, “anterior”, “immature”, “complications”, “outcome”, “ACL reconstruction”, “cruciate ligament anterior reconstruction”, “children”, “open physis”, “growth plate” and “skeletally immature”. The Boolean elements “and” and “or” were used. In addition, a manual search was undertaken of the bibliographic references of the studies found. The search methodology was verified by 2 authors.

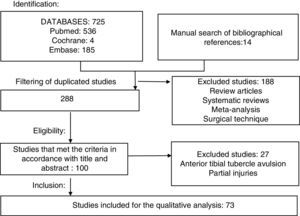

Selection of studiesThe titles and summaries of all the studies found and those that met the eligibility criteria were included. Once the complete studies were obtained, those that met the inclusion criteria were selected. Studies that included patients with tibial tubercle avulsion and partial injuries, and review or surgical technique articles were excluded.

The studies were extracted by one author and verified according to the eligibility criteria by 2 authors independently, based on the PRISMA statement.19

Variables analysedThe type of study, level of evidence, age, Tanner stage, associated meniscal injury, type of graft, follow-up time, length discrepancy, angular deformities, revision rates, other complications, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, subjective IKDC score, average Lysholm score, and average KT1000/KT2000 difference were analysed.

Evaluation of risk of biasThe studies were classified according to the level of evidence as per the description made by Wright et al. in 2003.20

Statistical analysisWe planned to perform the statistical analysis by means of meta-analysis; however, due to the diversity of the design of the studies, this was not possible. Therefore a descriptive analysis of the data was made by way of a systematic review. We calculated averages, frequencies and percentages to present the patients’ characteristics. The quantitative variables are presented as averages and standard deviations.

The studies were divided according to the type of physis-sparing surgery (extraphyseal and epiphyseal), partial transphyseal, transphyseal. They were also classified according to level of evidence.

The inclusion, exclusion and analysis methodology were specified in the protocol designed beforehand.

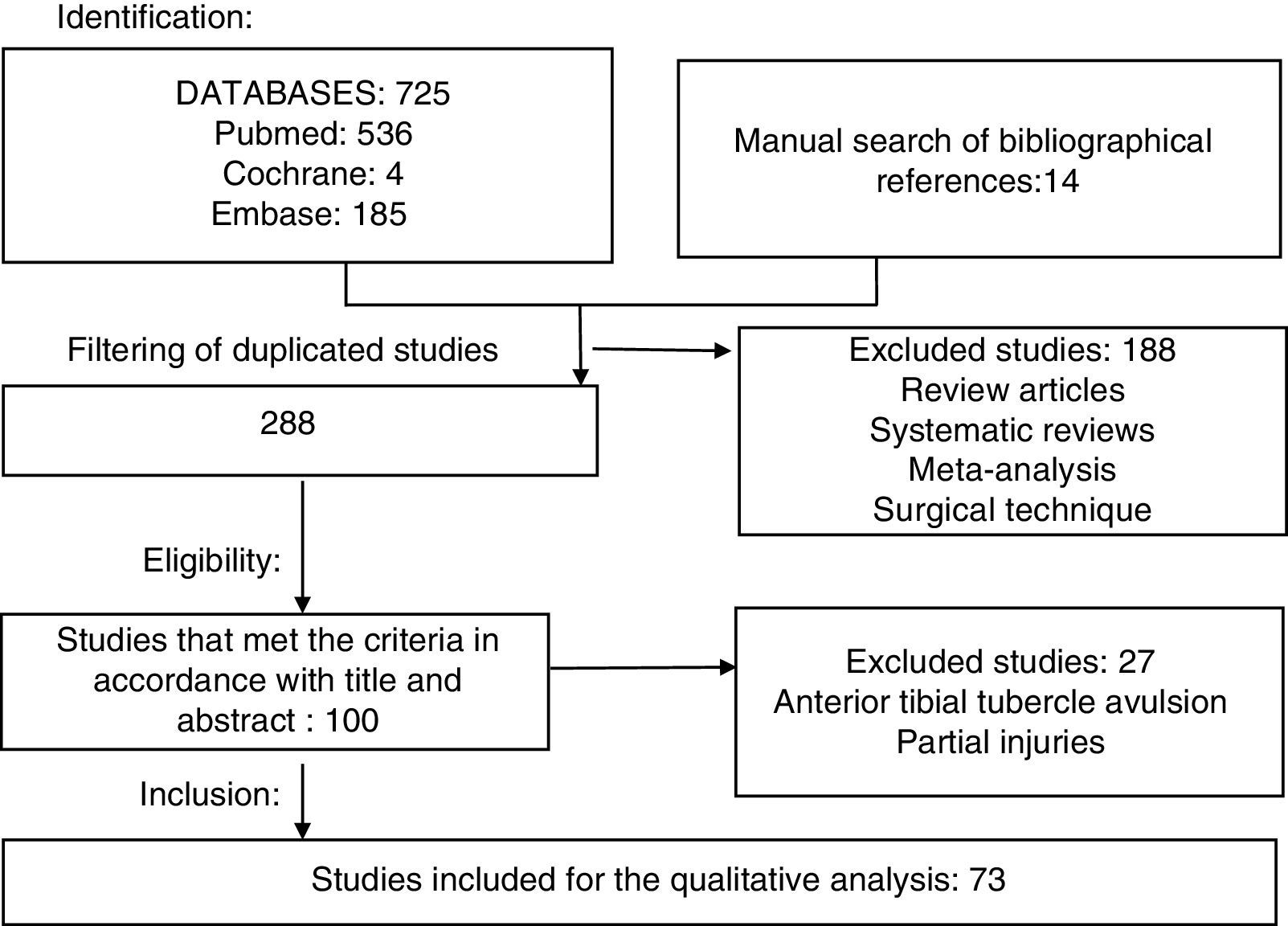

ResultsStudies selectedThe search of the PubMed, Cochrane and Embase databases yielded 725 results and the manual search found 14 additional studies. Two hundred and eighty-eight studies remained after filtering the duplicated studies. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 188 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were removed. The complete text of the 100 remaining studies was obtained, of which 27 were excluded that did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eventually 73 studies were included in the systematic review (Fig. 1).

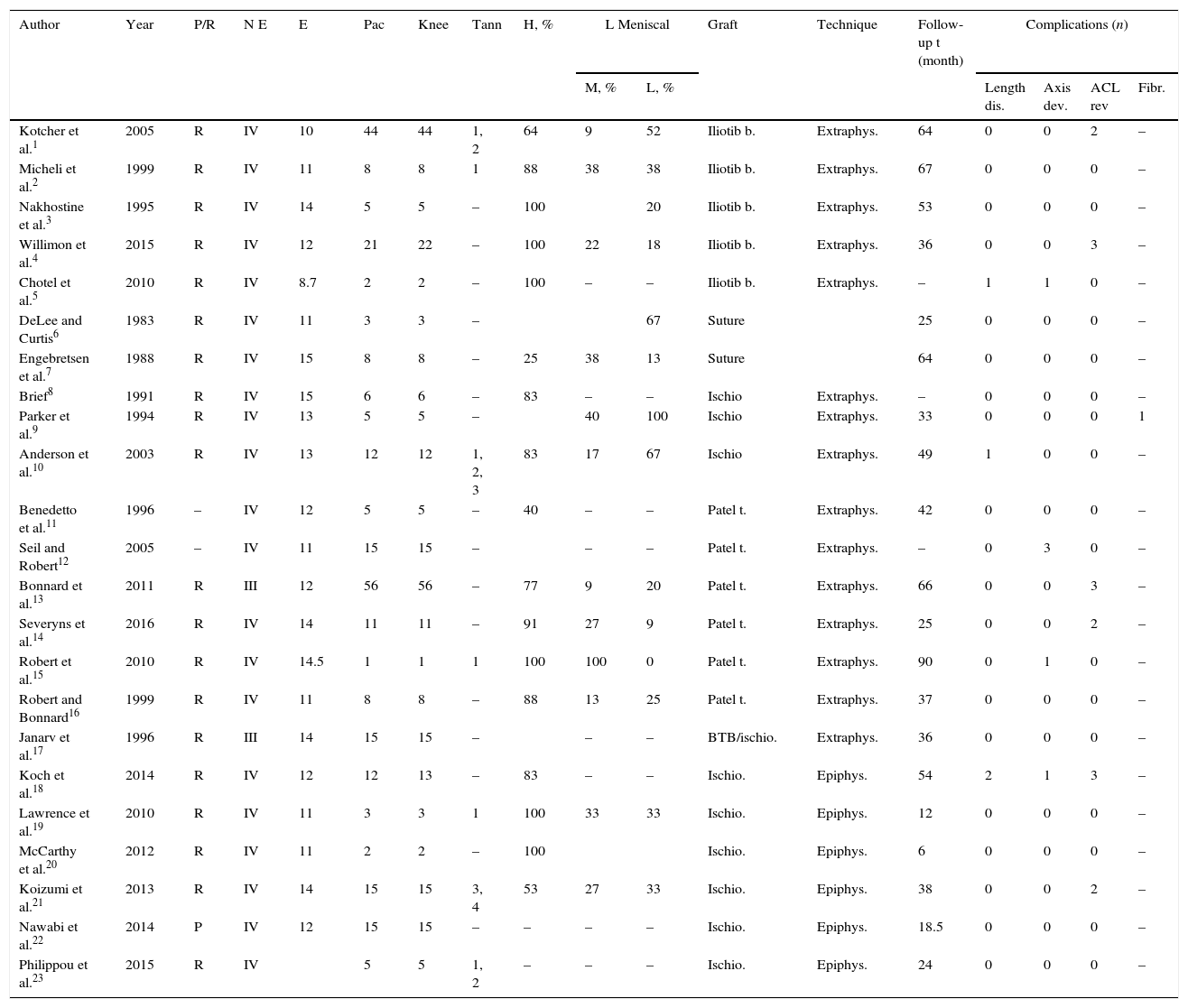

Characteristics of the studiesThe mean age of the patients included in the studies was 13.03 years (SD: 1.4); the average number of patients in the studies was 17.8 (17.9 knees). Seventy percent of the patients were male. There were 23 studies that mentioned the patients’ Tanner stage: Tanner 1–2 was the most frequent (43%). A total of 46 studies reported a rate of medial meniscal lesions with a mean percentage of 26% (0–100%), while 48 studies reported lateral meniscus lesions with an average of 30% (0–100%). The surgical techniques were divided into 3 groups: physeal-sparing (23 studies), partial physeal- sparing (8 studies) and transphyseal (42 studies). Many types of graft were used. The characteristics of each study are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Physis-sparing.

| Author | Year | P/R | N E | E | Pac | Knee | Tann | H, % | L Meniscal | Graft | Technique | Follow-up t (month) | Complications (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M, % | L, % | Length dis. | Axis dev. | ACL rev | Fibr. | ||||||||||||

| Kotcher et al.1 | 2005 | R | IV | 10 | 44 | 44 | 1, 2 | 64 | 9 | 52 | Iliotib b. | Extraphys. | 64 | 0 | 0 | 2 | – |

| Micheli et al.2 | 1999 | R | IV | 11 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 88 | 38 | 38 | Iliotib b. | Extraphys. | 67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Nakhostine et al.3 | 1995 | R | IV | 14 | 5 | 5 | – | 100 | 20 | Iliotib b. | Extraphys. | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| Willimon et al.4 | 2015 | R | IV | 12 | 21 | 22 | – | 100 | 22 | 18 | Iliotib b. | Extraphys. | 36 | 0 | 0 | 3 | – |

| Chotel et al.5 | 2010 | R | IV | 8.7 | 2 | 2 | – | 100 | – | – | Iliotib b. | Extraphys. | – | 1 | 1 | 0 | – |

| DeLee and Curtis6 | 1983 | R | IV | 11 | 3 | 3 | – | 67 | Suture | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

| Engebretsen et al.7 | 1988 | R | IV | 15 | 8 | 8 | – | 25 | 38 | 13 | Suture | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| Brief8 | 1991 | R | IV | 15 | 6 | 6 | – | 83 | – | – | Ischio | Extraphys. | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Parker et al.9 | 1994 | R | IV | 13 | 5 | 5 | – | 40 | 100 | Ischio | Extraphys. | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Anderson et al.10 | 2003 | R | IV | 13 | 12 | 12 | 1, 2, 3 | 83 | 17 | 67 | Ischio | Extraphys. | 49 | 1 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Benedetto et al.11 | 1996 | – | IV | 12 | 5 | 5 | – | 40 | – | – | Patel t. | Extraphys. | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Seil and Robert12 | 2005 | – | IV | 11 | 15 | 15 | – | – | – | Patel t. | Extraphys. | – | 0 | 3 | 0 | – | |

| Bonnard et al.13 | 2011 | R | III | 12 | 56 | 56 | – | 77 | 9 | 20 | Patel t. | Extraphys. | 66 | 0 | 0 | 3 | – |

| Severyns et al.14 | 2016 | R | IV | 14 | 11 | 11 | – | 91 | 27 | 9 | Patel t. | Extraphys. | 25 | 0 | 0 | 2 | – |

| Robert et al.15 | 2010 | R | IV | 14.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 100 | 100 | 0 | Patel t. | Extraphys. | 90 | 0 | 1 | 0 | – |

| Robert and Bonnard16 | 1999 | R | IV | 11 | 8 | 8 | – | 88 | 13 | 25 | Patel t. | Extraphys. | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Janarv et al.17 | 1996 | R | III | 14 | 15 | 15 | – | – | – | BTB/ischio. | Extraphys. | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| Koch et al.18 | 2014 | R | IV | 12 | 12 | 13 | – | 83 | – | – | Ischio. | Epiphys. | 54 | 2 | 1 | 3 | – |

| Lawrence et al.19 | 2010 | R | IV | 11 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 100 | 33 | 33 | Ischio. | Epiphys. | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| McCarthy et al.20 | 2012 | R | IV | 11 | 2 | 2 | – | 100 | Ischio. | Epiphys. | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | ||

| Koizumi et al.21 | 2013 | R | IV | 14 | 15 | 15 | 3, 4 | 53 | 27 | 33 | Ischio. | Epiphys. | 38 | 0 | 0 | 2 | – |

| Nawabi et al.22 | 2014 | P | IV | 12 | 15 | 15 | – | – | – | – | Ischio. | Epiphys. | 18.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Philippou et al.23 | 2015 | R | IV | 5 | 5 | 1, 2 | – | – | – | Ischio. | Epiphys. | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| Author | Year | P/R | LE | E | Pac | Knee | Tann | H | L Meniscal | Graft | Technique | Follow-up t (month) | Complications | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | L | Length dis. | Axis dev. | ACL rev | ||||||||||||

| Guzzanti et al.24 | 2003 | R | IV | 10.9 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 100 | 20 | 0 | Ischio | Fem. t | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hoffman et al.25 | 1998 | R | IV | – | 11 | 11 | – | – | 36 | 27 | Ischio | Fem. T | 56 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lipscomb et al.26 | 1986 | R | IV | – | 24 | 24 | – | 0 | 50 | 29 | Ischio | Tib. T | 35 | 1 | 0 | |

| Bisson et al.27 | 1998 | R | IV | – | 9 | 9 | – | 100 | – | – | Ischio | Tib. t | 39 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Nawabi et al.22 | 2014 | P | IV | 14.3 | 8 | 8 | – | – | – | – | Ischio | Tib. T | 18.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kawamura et al.28 | 2014 | P | IV | 10.7 | 12 | 12 | 1, 2 | 58 | 17 | 0 | Ischio | Tib. t | 180 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Cassard et al.29 | 2014 | R | IV | 13 | 28 | 28 | – | 71 | – | – | Ischio | Tib. t | 34 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Henry et al.30 | 2009 | R | III | 12.6 | 29 | 29 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 90 | 10 | 31 | Iliotib b./Q | Tib. t | 27 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Andrews et al.31 | 1994 | R | IV | 13.5 | 8 | 8 | – | 100 | 50 | 50 | F. lata/Ach. allo | Tib. t | 58 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

Iliotib b.: iliotibial band; Axis dev.: axis deviation; Length dis.: length discrepancy; Epiphys: epiphyseal; Extraphys: extraphyseal; Fibr: arthrofibrosis; M: males; ischio: ischiotibial; L: lateral; M: medial; LE: level of evidence; P: prospective; Pat: patient; R: retrospective; Knee: knees; ACL rev: ACL revision; Patel t.: patellar tendon; Tann: Tanner stage; follow-up t: follow-up time.

Iliotib band: iliotibial band; Axis dev.: axis deviation; Length dis.: length discrepancy; Ischio: ischiotibial; M: medial; L: lateral; LE: level of evidence; P: prospective; Pat: patient; Q: quadriceps; R: retrospective; Knee: knees; ACL rev: ACL revision; Fem t.: Femoral transphyseal; Tib t: tibial transphyseal; Tann: Tanner stage; M: males; Follow-up t: Follow-up time.

Transphyseal.

| Author | Year | P/R | LE | Age | P | K | Tann | H | L Meniscal | Graft | Follow-up t (month) | Length dis. | Complications (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | L | Axis dev. | ACL rev | Fibr. | ||||||||||||

| Aichroth et al.32 | 2002 | R | III | 13 | 45 | 47 | – | 71% | 19% | 17% | Ischio | 49 | 0 | 0 | 3 | – |

| Attmanspacher et al.33 | 2002 | P | IV | 10 | 8 | 8 | – | 13 | Ischio | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | ||

| Bollen et al.34 | 2008 | P | IV | 13.4 | 5 | 5 | 1, 2 | 100% | 20% | 20% | Ischio | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Casper et al.35 | 2006 | R | IV | 14.7 | 13 | 13 | – | 54% | – | – | Ischio | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Gaulrapp and Haus36 | 2006 | R | IV | 14.6 | 15 | 15 | – | – | – | – | Ischio | 78 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

| Kocher et al.37 | 2007 | R | IV | 14.7 | 59 | 61 | – | 39% | 16% | 41% | Ischio | 43 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Liddle et al.38 | 2008 | P | IV | 12.1 | 17 | 17 | 1, 2 | 82% | 41% | 24% | Ischio | 44 | 0 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Marx et al.39 | 2008 | R | IV | 13.4 | 55 | 55 | 60% | 25% | 42% | Ischio | 42 | 0 | 0 | 3 | – | |

| Matava and Siegel40 | 1997 | R | IV | 14.8 | 8 | 8 | – | 75% | 13% | 50% | Ischio | 32 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

| Koman et al.40 | 1999 | R | IV | 14.3 | 1 | 1 | – | 100% | 0% | 0% | Ischio | 35 | 0 | 1 | 0 | – |

| McIntosh et al.41 | 2006 | R | IV | 13.6 | 16 | 16 | – | 69% | 31% | 13% | Ischio | 41 | 1 | 0 | 2 | – |

| Schneider et al.42 | 2008 | R | IV | 15 | 15 | 53% | 53% | 53% | Ischio | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | ||

| Higuchi et al.43 | 2009 | P | IV | 14.5 | 10 | 10 | – | 40% | Ischio | 6 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Seon et al.44 | 2005 | R | IV | 14.7 | 11 | 11 | 2, 3, 4 | 100% | 55% | 55% | Ischio | 78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Sobau and Ellermann45 | 2004 | R | IV | 14.2 | 25 | 25 | – | 24% | 40% | Ischio | 31 | 0 | 0 | 3 | – | |

| Courvoisier et al.46 | 2011 | R | IV | 14 | 37 | 37 | – | 46% | 11% | 21% | Ischio | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Streich et al.47 | 2010 | P | II | 13.7 | 94 | 94 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 60% | 20% | 10% | Ischio | 38 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Hui et al.48 | 2012 | R | IV | 12 | 12 | 12 | 1, 2 | 75% | Ischio | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | ||

| Kumar et al.49 | 2013 | P | IV | 11.3 | 32 | 32 | 1, 2, 3 | 89% | 19% | 22% | Ischio | 72.3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Lemaitre et al.50 | 2014 | R | IV | 13.5 | 13 | 14 | – | – | 14% | 36% | Ischio | 15.5 | 0 | 2 | 0 | – |

| Calvo et al.51 | 2014 | R | IV | 13 | 27 | 27 | 2, 3, 4 | 59% | 37% | 7% | Ischio | 127 | 0 | 0 | 4 | – |

| Larson et al.52 | 2016 | R | IV | 13.5 | 29 | 30 | 1, 2, 3 | 45% | 13% | 33% | T. ant/Ischio | 48.1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | – |

| Shifflett et al.53 | 2016 | R | IV | 14.6 | 4 | 4 | – | 50% | – | – | Ischio | 30.7 | 0 | 4 | 0 | |

| Thompson et al.54 | 2006 | – | IV | – | 30 | 30 | – | – | – | – | Ischio/allo. | 36 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Ach. | ||||||||||||||||

| Arbes et al.55 | 2007 | R | IV | – | 7 | 7 | – | – | – | – | Patel t. | 65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Lukas et al.56 | 2007 | 13.2 | 16 | 16 | – | 13% | 13 | Patel t. | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| McCarroll et al.57 | 1994 | R | III | 13.7 | 60 | 60 | – | 48 | – | – | Patel t. | 50 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Shelbourne et al.58 | 2004 | R | IV | 14.8 | 16 | 16 | 3, 4 | 69 | 38 | 56 | Patel t. | 41 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

| Memeo et al.59 | 2012 | R | IV | 14.4 | 10 | 10 | 3 | – | – | – | Patel t. | 24.9 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – |

| Cohen et al.60 | 2009 | R | IV | 13.3 | 26 | 26 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | 42 | 19 | 3 | Q | 45 | 0 | 0 | 3 | – |

| Mauch et al.61 | 2011 | R | IV | 13 | 49 | 49 | – | 57 | – | – | Q | 60 | 0 | 1 | 0 | – |

| Redler et al.62 | 2012 | R | IV | 14.2 | 18 | 18 | 67 | 22 | 33 | Q | 43.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |

| Kohl et al.63 | 2014 | P | IV | 12.8 | 15 | 15 | 2, 3, 4 | 80 | – | – | Q | 49 | 2 | 1 | 0 | – |

| Lo et al.64 | 1997 | R | IV | 12.9 | 5 | 5 | – | – | 40 | 40 | Isch/Q | 89 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Vaquero et al.65 | 2005 | 13.6 | 15 | 15 | – | 40 | Patel t./ischi | 27 | 0 | 0 | 1 | – | ||||

| Pressman et al.66 | 1997 | R | III | – | 11 | 11 | – | – | – | – | Patel t./ischi | – | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Edwards and Grana67 | 2001 | 13.7 | 19 | 20 | – | 37 | 20 | 65 | Patel t./ischi | 34 | 1 | 1 | 2 | – | ||

| Sankar et al.68 | 2006 | R | IV | 15.6 | 12 | 12 | – | 50 | 33 | 58 | Ach. allo | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Aronowitz et al.69 | 2000 | 13.4 | 15 | 15 | 47 | – | – | Ach. allo | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

| Fuchs et al.70 | 2002 | R | IV | 13.2 | 10 | 10 | – | 60 | 50 | 40 | Patel t. allo. | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

| Cho et al.71 | 2011 | R | IV | 12.4 | 4 | 4 | 2, 3 | 0 | – | – | Ant t. allo | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | – |

Allo: allograft; Ach: Achilles; Axis dev.: axis deviation; Length dis.: length discrepancy; F. lata: fascia lata; M: males; ischio: ischiotibial; L: lateral; M: medial; LE: level of evidence; P: patient; P: prospective; Q: quadriceps; R: retrospective; K: knees; ACL rev: ACL revision; Ant t.: anterior tibial; Patel t.: patellar tendon; Tann: Tanner stage; Follow-up t: follow-up time.

The 73 studies included in the review had a level of evidence II–IV. One study was classified as level II, 6 studies as level III, and the remainder as level IV. Of the total number of studies, only 10 were prospective, 55 were retrospective, and 8 did not mention a design type. Most of the studies were case and cohort series, where there was no blinding, and did not include a control group. These types of studies enable hypotheses to be formulated but they cannot be verified.

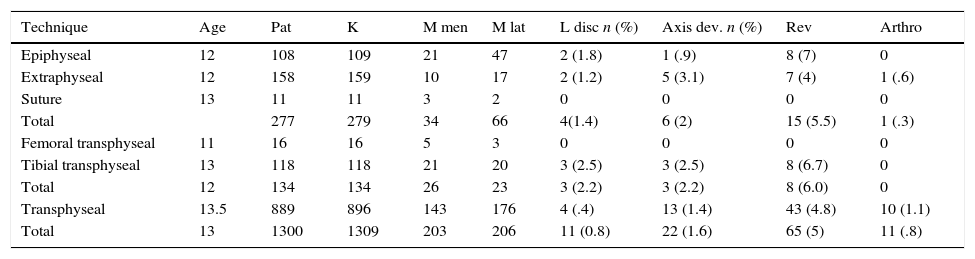

Physeal-sparing techniquesA total 23 studies described physeal-sparing techniques, for a total of 277 patients (21% of the total), with a mean age of 12.3 years (range: 8.7–15). Four cases of lower limb length discrepancy were presented (1.4%)—all due to overgrowth—, 6 patients had axis deviation (2%)—4 valgus deformities and 2 varus deformities—, there were 15 revisions (5.5%) and one case of arthrofibrosis (0.3%). Two studies performed a primary repair, with a total of 11 patients, and described no associated complications. Another 7 studies described epiphyseal techniques in a total of 108 patients (109 knees), with a mean age of 12 years (range: 11–14); 10 cases of medial meniscal injury (23%), 17 lateral meniscus (29%), 2 cases of length discrepancy (1.8%), one case of axis deviation (0.9%), 8 revision cases (7%), there was no arthrofibrosis. Fourteen studies described extraphyseal techniques, with a total of 158 patients (159 knees), with a mean age of 12 years, with 7 cases of length discrepancy, 2 of axis deviation, 7 revision surgeries, and one case of arthrofibrosis (Table 3).

Complications according to surgical technique.

| Technique | Age | Pat | K | M men | M lat | L disc n (%) | Axis dev. n (%) | Rev | Arthro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epiphyseal | 12 | 108 | 109 | 21 | 47 | 2 (1.8) | 1 (.9) | 8 (7) | 0 |

| Extraphyseal | 12 | 158 | 159 | 10 | 17 | 2 (1.2) | 5 (3.1) | 7 (4) | 1 (.6) |

| Suture | 13 | 11 | 11 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 277 | 279 | 34 | 66 | 4(1.4) | 6 (2) | 15 (5.5) | 1 (.3) | |

| Femoral transphyseal | 11 | 16 | 16 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tibial transphyseal | 13 | 118 | 118 | 21 | 20 | 3 (2.5) | 3 (2.5) | 8 (6.7) | 0 |

| Total | 12 | 134 | 134 | 26 | 23 | 3 (2.2) | 3 (2.2) | 8 (6.0) | 0 |

| Transphyseal | 13.5 | 889 | 896 | 143 | 176 | 4 (.4) | 13 (1.4) | 43 (4.8) | 10 (1.1) |

| Total | 13 | 1300 | 1309 | 203 | 206 | 11 (0.8) | 22 (1.6) | 65 (5) | 11 (.8) |

Arthro: arthrofibrosis; L disc: length discrepancy; Axis dev.: axis deviation; L men: lateral meniscus; M men: medial meniscus; Pat: patients; Rev: revision; K: knee.

Nine studies were included, with a total of 134 patients and an average age of 12 years. There were 26 cases of medial meniscus injuries (19%) and 23 lateral meniscus injuries (17%), 3 cases of length discrepancy (reduced length) and 3 cases of axis deviation (2.2%). The revision rate was 6% (8 cases); there were no cases of arthrofibrosis. Seven of the studies described the tibial transphyseal technique, with a total of 118 patients. All the cases of length discrepancy, axis deviation and revision presented using the tibial transphyseal technique (Table 3).

Transphyseal techniquesForty-one studies described transphyseal techniques, with a total of 889 patients and 896 knees, with an average age of 13.5 years: they covered 143 cases of medial meniscus injuries and 176 of lateral meniscus injuries (16% and 20% respectively). Four cases of lower limb length discrepancy were presented (0.4%) (one case of overgrowth), 11 cases of axis deviation of the limb (1.4%), 9 cases due to valgus deformity and the other 2 due to recurvatum. There were 43 cases of revision surgery (4.8%), (Table 3).

Subdivision according to Tanner stagingTwenty-three studies described their results according to the Tanner stage. However, only 13 described Tanner stages 1–2 and 3–4. Another 10 studies included patients with Tanner stage 1–3 studies Tanner stages 3–4. In the studies with Tanner stage 1–2, one case of axis deviation was presented (0.8%), 6 cases of revision surgery (5%) and no case of length discrepancy. In the studies with Tanner stage 3–4, there were 4 cases of revision (10%) and there were no cases of lower limb growth alterations.

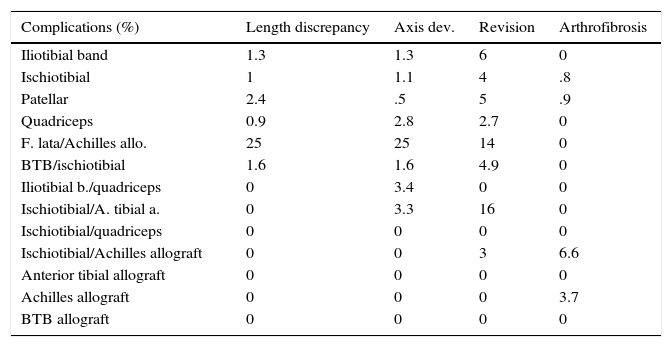

Subdivision according to type of graftMany grafts were used: iliotibial band (5 studies), ischiotibial tendon (40 studies), patellar tendon (10 studies), quadriceps (4 studies), Achilles allograft (2 studies), BTB allograft (one study), anterior tibial allograft,1 a combination of several of the above (20 studies). The grafts that presented length discrepancy cases were: iliotibial band (1.3%), ischiotibial tendon (1%), patellar tendon (2.4%), quadriceps (0.9%), fascia lata/Achilles allograft (25%), BTB/ischiotibial tendon (1.6%) (p<0.05). The cases of axis deviation were distributed as follows: iliotibial band (1.3%), ischiotibial tendon (1.1%), patellar tendon (0.5%), quadriceps (2.8%), fascia lata/Achilles allograft (25%), BTB/ischiotibial (1.6%), iliotibial band/quadriceps (3.4%), ischiotibial/Achilles (3.3%) (p<0.05) (Table 4).

Complications according to graft type.

| Complications (%) | Length discrepancy | Axis dev. | Revision | Arthrofibrosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iliotibial band | 1.3 | 1.3 | 6 | 0 |

| Ischiotibial | 1 | 1.1 | 4 | .8 |

| Patellar | 2.4 | .5 | 5 | .9 |

| Quadriceps | 0.9 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0 |

| F. lata/Achilles allo. | 25 | 25 | 14 | 0 |

| BTB/ischiotibial | 1.6 | 1.6 | 4.9 | 0 |

| Iliotibial b./quadriceps | 0 | 3.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Ischiotibial/A. tibial a. | 0 | 3.3 | 16 | 0 |

| Ischiotibial/quadriceps | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ischiotibial/Achilles allograft | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6.6 |

| Anterior tibial allograft | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Achilles allograft | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.7 |

| BTB allograft | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

F. lata allo.: fascia lata allograft; A. tibial a: anterior tibial allograft anterior; iliotibial b.: iliotibial band; Dev.: deviation.

The incidence of ACL injuries in skeletally immature patients is increasing. Shea et al. reported that these injuries constituted 6.7% of all football injuries from the age of 5–18 years, and 30.8% of knee injuries in this population.21

The incidence of injuries associated with ACL tear is considered high.18 Millet et al. found associated intra-articular injuries in 67% of patients with ACL tears.22 Moreover, in the same study they found that delayed surgery increased the incidence of meniscal injuries (from 37% to 53.4%, with a cut-off point of 5 months). Chhadia et al. demonstrated in a retrospective study of 1252 patients that the risk of meniscal and irreparable joint cartilage injury increased when the surgical procedure was delayed (meniscal injury: 6 months OR: 1.8; >12 months OR: 2.19; p: 0.01; joint cartilage >12 months; OR: 1.57; p: 0.009).23 However, Moksnes et al. found a low incidence of meniscal injuries after conservative management, with a rate of 19%.24 This review revealed a prevalence of 26% of medial meniscus injury and a prevalence of 30% of lateral meniscus injury, and no relationship was found between the delayed surgery time and the increase in meniscal injuries (lateral p=0.5; medial p=0.1).

Conservative treatment of these injuries was previously considered the treatment of choice in skeletally immature patients, because surgical reconstruction can increase the risk of physeal bars, which result in altered lower limb growth.25,26 Vavken et al. performed a systematic review of the treatment of ACL injuries and found that conservative treatment had poor clinical outcomes and a high incidence of secondary defects, including meniscal and joint cartilage injuries. However, this review included studies with level of evidence III and IV.27 Ramski et al. undertook a meta-analysis to compare functional outcomes, return to previous activity, symptomatic meniscal injuries and instability in patients treated conservatively vs surgical management: 33 studies reported instability, which was more common in the conservatively managed group (13.6 vs 75%; p<0.01). Meniscal injuries were more common in the group that was not managed surgically (35.4 vs 3.9%; p=0.02), and also had better functional outcomes on the a International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) scale (p=0.02).2 Similar results have been described by other authors.29,30

Many ACL reconstruction techniques have been described. They can be classified into 3 groups according to the location of the tunnels with respect to the physis: physis-sparing, partial transphyseal and total transphyseal.17

From a theoretical point of view, the transphyseal techniques can generate altered lower limb growth. Many studies on animals and humans have been undertaken in this regard. Stadelmaier et al. compared the physeal defect with and without the use of soft tissue interposition in the graft in dogs, and concluded that the use of tissue interposition prevented the formation of physeal bars.31 Other animal studies have shown that physeal drill injury of 7–9% generates altered limb growth even if soft tissue interposition is used.32 Kercher et al. reviewed 31 patients with transphyseal reconstruction of the ACL using MRI and three-dimensional modelling, and found that 8mm tunnels affected <3% of the physeal area, and concluded that the tunnel diameter is more damaging than the drilling angle.16

Keading et al. performed a systematic review with the aim of determining the best surgical technique for Tanner stage I, II and III patients under the age of 15: they found excellent clinical and functional outcomes, and a low complication rate with the transphyseal and the physis-sparing techniques in Tanner stage II and III patients. In addition, they made a recommendation of use for physis-sparing techniques in Tanner I patients; however, the review did not include studies with transphyseal techniques in Tanner I patients.33 Collins et al. performed a systematic revision that analysed lower limb growth alterations according to surgical technique, type of graft and fixation method. The review included 21 studies, with an average age of 13 years, there were 39 cases of altered growth, of which 25% of the angular deformities and 47% of the length discrepancies occurred with the physis-sparing techniques. Furthermore, 62% of the 29 cases of length discrepancy were due to overgrowth of the limb (50% physis-sparing techniques).

The review's limitations are the low level of evidence of the studies included and the abnormality parameters in length discrepancy and angular deformity, which are not standardised.34 Frosch et al. performed a meta-analysis which included 55 studies and 935 patients; the transphyseal techniques were associated with a lower risk of length discrepancy or axis deviation compared to the physis-sparing techniques (1.9 vs 5.8%; RR: 0.34; 95% CI: 0.14–0.81), but were associated with a greater risk of rerupture (4.2 vs 1.4%; RR: 2.91; 95% CI: 0.70–12.12).35

Most of the cases of axis deviation presented recurvatum and valgus. This might be because the anterior medial part of the epiphysis can be injured when the tibial tunnel is made and cause premature closure of the anterior physis. Another explanation might be that the graft, when placed distal to the tibial physis (extraphyseal), creates tension and blocks the growth of the anterior portion of the physis.36,37

In our review, we found similar rates of length discrepancy and axis deviation with the different surgical techniques, with a greater percentage of cases of length discrepancy in the partial transphyseal group, compared to the physis-sparing and transphyseal techniques (2.2; 1.4% and 0.4%, respectively).

With regard to the complications associated with the type of graft, it was found that the patients using a fascia lata or Achilles tendon allograft presented 25% axis deviation and length discrepancy; all the cases were presented in the study by Andrew et al. who used the tibial transphyseal and femoral over-the-top technique. The 2 cases of length discrepancy had a difference of 10 and 8mm in tibial length, but the difference in length of the entire limb was 3 and 7mm compared to the healthy leg.38 The use of patellar tendon was associated with a greater percentage of length discrepancy compared to ischiotibial tendon (2.4% vs 1%). This finding coincides with the meta-analysis by Frosch et al., in which there was a slight risk of length discrepancy and axis deviation in the BTB group, but not statistically significant.35

LimitationsMost of the studies had a level of evidence IV. This means that none of the studies used blinding. Although associations can be made between the variables, we could not establish causality, and in the case of this review, the causality between the type of surgical technique used and the complications presented cannot be established. Moreover, the characteristics of the different studies were very heterogeneous, which makes indirect comparison difficult. In addition, the definition of length discrepancy and axis deviation was not established; therefore the studies might have different cut-off points.

ConclusionsThis systematic review demonstrates a low rate of complications related to lower limb growth, arthrofibrosis and revision surgery in patients under the age of 18 years. Therefore the different surgical techniques are safe. There was a higher percentage of cases of length discrepancy with the physis-sparing techniques and axis deviation with the partial transphyseal technique but, due to the level of evidence of the studies, causality cannot be established.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments with human beings or animals have been performed while conducting this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Tovar-Cuellar W, Galván-Villamarín F, Ortiz-Morales J. Complicaciones asociadas a las diferentes técnicas de reconstrucción del ligamento cruzado anterior en menores de 18 años: Revisión sistemática. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:55–64.