To evaluate the efficacy of topical tranexamic acid topical in cementless total hip arthroplasty from the point of view of bleeding, transfusion requirements and length of stay, and describe the complications of use compared to a control group.

Material and methodsA prospective, randomised, double-blinded and controlled study including all patients undergoing cementless total hip arthroplasty in our centre between June 2014 and July 2015. Blood loss was estimated using the formula described by Nadler and Good.

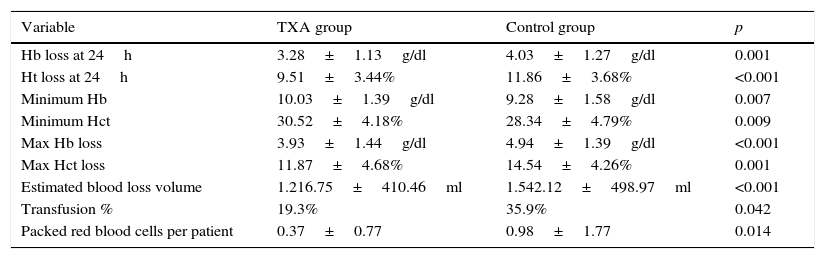

ResultsThe final analysis included 119 patients. The decrease in haemoglobin after surgery was lower in the tranexamic acid group (3.28±1.13g/dL) than in the controls (4.03±1.27g/dL, p=0.001) and estimated blood loss (1216.75±410.46mL vs. 1542.12±498.97mL, p<0.001), the percentage of transfused patients (35.9% vs. 19.3%, p<0.05) and the number of transfused red blood cell units per patient (0.37±0.77 vs. 0.98±1.77; p<0.05). There were no differences between groups in the occurrence of complications or length of stay.

ConclusionsThe use of topical tranexamic acid in cementless total hip arthroplasty results in a decrease in bleeding and transfusion requirements without increasing the incidence of complications.

Evaluar la eficacia del ácido tranexámico tópico en la artroplastia total de cadera no cementada desde el punto de vista del sangrado, las necesidades transfusionales y la estancia media, así como describir las complicaciones derivadas de su uso respecto a un grupo control.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo, aleatorizado, controlado y doble ciego que incluye todos los pacientes intervenidos de artroplastia total de cadera no cementada en nuestro centro entre junio de 2014 y julio de 2015. La pérdida de sangre se estimó mediante la fórmula descrita por Nadler y Good.

ResultadosEl análisis final incluyó 119 pacientes. El descenso de hemoglobina tras la cirugía fue menor en el grupo del ácido tranexámico (3,28±1,13g/dL) que en el control (4,03±1,27g/dL, p=0,001), así como el volumen estimado de sangre perdida (1.216,75±410,46mL vs. 1.542,12±498,97mL, p<0,001), el porcentaje de pacientes transfundidos (35,9% vs. 19,3%, p<0,05) y el número de unidades de hematíes transfundidas por paciente (0,37±0,77 vs. 0,98±1,77, p<0,05). No hubo diferencias entre los grupos en la aparición de complicaciones ni en la estancia media.

ConclusionesEl uso de ácido tranexámico tópico en la artroplastia total de cadera no cementada produce una disminución en las necesidades transfusionales y el sangrado sin aumentar la incidencia de las complicaciones.

Total hip replacement is a surgical procedure that improves quality of life and combats the pain caused by joint degeneration or injury. Bleeding is one of the most common problems associated with this procedure. Bleeding occurs during the operation and will continue, usually to a lesser extent, during the postoperative period. It is estimated that the average blood loss is 1236mL1 and it is also possible that many surgeons underestimate this blood loss.2 The most notable direct consequence of this bleeding is the need to transfuse up to 30% of patients according to the series.3,4 Blood transfusions are a finite resource and not always available, are generally costly,5 and carry potential risks such as the transmission of infection, and immune and anaphylactic reactions.6

Antifibrinolytics drugs are able to prevent clot degradation after they form, increasing their duration, and thus have a net procoagulant effect. Many studies have demonstrated that antifibrinolytics can reduce bleeding, the need for transfusions and even the costs involved in hip and knee joint replacement surgery,7 adult spinal reconstructive surgery,8 and paediatric scoliosis surgery.9

Tranexamic acid has a very similar molecular structure to that of the amino acid lysine and creates a reversible block of the specific site for this amino acid in the plasminogen molecule, preventing it from bonding to the fibrin of the blood clot and thus inhibiting the activation of the plasminogen-tPA-fibrin complex.10

Orthopaedic surgeons have become increasingly interested in tranexamic acid in recent years. On the one hand, it has been demonstrated in a great many publications to be a safe and effective drug even in high doses11 and on the other, its topical use appears to facilitate application without compromising its efficacy.12,13

Although minor adverse reactions after taking the drug have been described such as nausea, vomiting and orthostatism14 and, to a lesser extent, renal failure and epileptic seizures,15 theoretically the most significant problem that can occur after using tranexamic acid is thrombophilia. Since this is a procoagulant drug there might be an increased risk of major adverse events such as pulmonary thromboembolism or deep vein thrombosis. This is why patients with a history of thrombotic disorder are excluded from most published papers.16–18 Nevertheless, practically none of the published studies have been able to demonstrate this risk.

Moreover, as this is a cheap drug, many authors acknowledge that its use might constitute a financial saving, up to 25% in some cases, in the peri-operative management of these patients.7

This study was planned with the aim of assessing the reduction of bleeding and the needs for a transfusion of patients undergoing primary total cementless hip arthroplasty via an anterolateral approach using 1.5g topical tranexamic acid during surgery.

Material and methodsA prospective, randomised, double blinded clinical study was undertaken, which included all the patients operated in our hospital's Orthopaedic Department for total hip arthroplasty via the anterolateral approach (Watson-Jones), using different models of cementless prostheses, in the period between June 2014 and July 2015.

Inclusion criteriaPatients aged over the age of 18 years, operated in our centre during the study period (between June 2014 and July 2015) for cementless total hip arthroplasty using an anterolateral approach (Watson-Jones), after obtaining their informed consent.

Exclusion criteriaPatients who were allergic to tranexamic acid (Amchafibrin®) or any of its components, who had experienced adverse reactions previously after administration of the drug and when the reason for surgery was an acute fracture (admitted via the emergency department) were excluded from the study.

Sample sizeThe sample size calculated to demonstrate a reduction in transfusion rate from the theoretical 30% to 10%, with statistical power of 80%, a significance level of 5% and losses of 10% was 124 patients (62 in each arm of the study).

Groups and maskingWe describe a control group and an intervention or study group (tranexamic acid). A simple computer-obtained randomisation list was used to allocate the patients to each group.

During anaesthetic induction, once it was known which group the patient belonged to according to the randomisation list, the circulating theatre nurse prepared a syringe with 60ml sterile physiological serum for the control group, and for the study group a solution of 45ml physiological serum and 3 ampoules of Amchafibrin® (each syringe contained 500mg tranexamic acid and 5ml serum). The preparation was given to all of the cases at three different times during the operation: 20ml were applied in the acetabular bed, once it had been milled and before impaction of the definitive component, and left to act for 3min. Another 20ml were applied once the medullary cavity of the femur had been prepared before impaction of the definitive stem, leaving 3min for the drug to act. The final 20ml were applied on completion of the operation through a Redon drain, once the wound had been sutured. The drain remained closed for 60min in all the patients and maintained for 48h.

Measurement of results and variablesThe principal measurement of the results of this study was the transfusion rate. Patients with a haemoglobin less than or equal to 25% detected on control tests at any time during their admission (at 24h and then every 48h until discharge) were transfused.

The demographic variables and any cardiovascular history were also recorded and other variables relative to the intervention (such as the type of prosthesis or duration of the surgery), the haemoglobin levels and haematocrit on the various analytical tests on admission, the number of red blood cell units transfused per patient, the estimated volume of blood loss according the TVP formulae of Nadler19 and Good20 and complications (in particular PTE and DVT).

Data collectionSpecific sheets were designed for data collection. Data from the hospital's electronic clinical histories were obtained and if no information of interest was found, contact was made by telephone directly to the patients or their near relatives to gather data. All of the data were collected once all the patients had been gathered in line with the sample size calculated, at which time the authors knew the randomisation sequence. The data were recorded on an Excel 2011 sheet for Mac (Microsoft® Corporation) and after filtering were analysed by an expert using SPSS v. 15.0 (SPSS Inc. 1989–2006). A loss of values above 15% in a particular variable was considered a potential bias of the study.

StatisticsThe Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check normal distribution of a variable. The normal distribution variables are described as mean±standard deviation (SD) and those that were not normal distribution as median and interquartile range. In turn, the qualitative variables are described in absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) of the categories. The Chi-square test was used to study the association between qualitative variables with Fisher's exact test or likelihood ratio test depending on their application conditions. The Student t-test or Mann–Whitney U test were used to study the differences between means, depending on the application conditions, for 2 groups. An intention to treat analysis was made, calculating measures of association and effect with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI). Logistic regression analysis was also undertaken to explain the result variable (transfusion rate), including analysis of age, sex, study group and the variables that resulted associated to the study variable in the bivariate analysis. A significance level for all the tests was considered for a p value ≤0.05.

Ethical aspectsThis paper was undertaken following the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 (last amended in 2013). The study was approved by the Research Commission of the Hospital Universitario Río Hortega-Área Oeste of Valladolid. The patients’ informed consent was obtained for participation in the study.

There are no conflicts of interest to declare, and no funding was received from public or private bodies.

ResultsBetween June 2014 and July 2015, 122 patients were included in the study (124 primary hip arthroplasties). Of this initial group, 2 patients could not be identified because the label was missing with their personal data at the time the data was analysed. Another patient was excluded because they had a subcapital hip fracture implanted with a partial Thompson prosthesis. The final analysis was performed on 119 patients (121 interventions, since 2 patients were operated on both hips at different times). Fifty-two point nine percent of the sample was randomised to the control group and the remaining 47.1% to the study group (tranexamic acid).

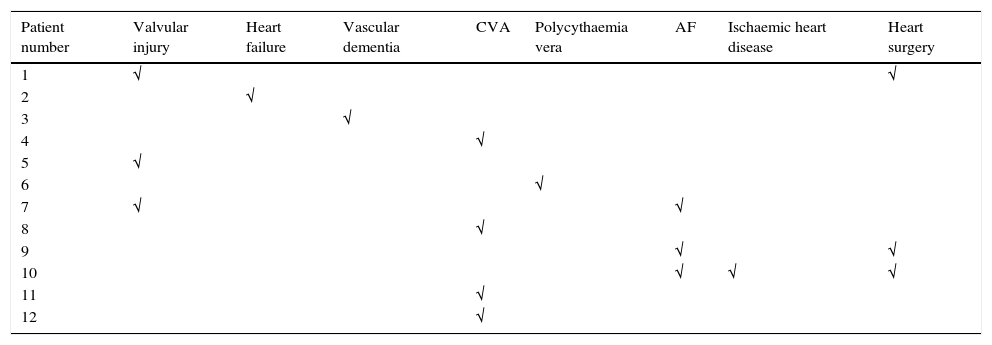

The mean age of the operated patients was 65.48±12.48 years, mean weight 75.02±14.38kg and height 164.30±8.11cm; 63 of the patients operated were females (52.1%) and 58 were males (47.9%). Fifty-four point five percent of the interventions were to the right side (66 patients) and the remaining 45.5% to the left (55 patients). None of these filiation variables presented differences between the study group and the control group. A total of 12 patients (9.9%) had some type of cardiovascular history, the most frequent being CVA, atrial fibrillation and coronary revascularisation surgery (Table 1). Fourteen percent of the sample (17 patients) took some type of anticoagulant or antiplatelet medication. No significant differences were found between the study and control groups for any of these variables.

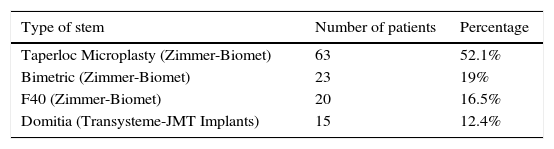

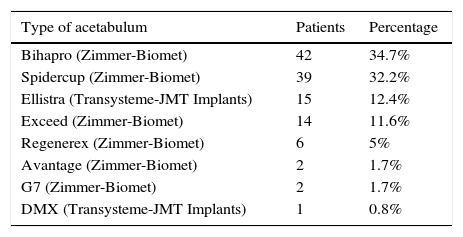

The surgery time (73.77±18.18min), the size and type of stem and acetabulum (Tables 2 and 3), head and insert and mean hospital stay (6±1 day) showed no significant differences either between the study and control group.

Types of acetabulum.

| Type of acetabulum | Patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Bihapro (Zimmer-Biomet) | 42 | 34.7% |

| Spidercup (Zimmer-Biomet) | 39 | 32.2% |

| Ellistra (Transysteme-JMT Implants) | 15 | 12.4% |

| Exceed (Zimmer-Biomet) | 14 | 11.6% |

| Regenerex (Zimmer-Biomet) | 6 | 5% |

| Avantage (Zimmer-Biomet) | 2 | 1.7% |

| G7 (Zimmer-Biomet) | 2 | 1.7% |

| DMX (Transysteme-JMT Implants) | 1 | 0.8% |

Haemoglobin levels and haematocrit prior to the intervention and at 24h were similar in both groups.

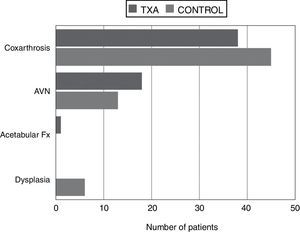

Significant differences were found between the patients who were given tranexamic acid and those in the control group in reduced haemoglobin levels and haematocrit in the first 24h from the earlier levels after the intervention, the lowest point reached during admission and maximum decrease in haemoglobin levels and haematocrit (compared to preoperative levels), estimated blood loss, transfusion rate and number of red blood cell units transfused per person, all in favour of the tranexamic acid group (Table 4). The “diagnosis” variable was also unequally distributed between the groups (Fig. 1).

Variables with significant differences between the TXA group and the control group.

| Variable | TXA group | Control group | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hb loss at 24h | 3.28±1.13g/dl | 4.03±1.27g/dl | 0.001 |

| Ht loss at 24h | 9.51±3.44% | 11.86±3.68% | <0.001 |

| Minimum Hb | 10.03±1.39g/dl | 9.28±1.58g/dl | 0.007 |

| Minimum Hct | 30.52±4.18% | 28.34±4.79% | 0.009 |

| Max Hb loss | 3.93±1.44g/dl | 4.94±1.39g/dl | <0.001 |

| Max Hct loss | 11.87±4.68% | 14.54±4.26% | 0.001 |

| Estimated blood loss volume | 1.216.75±410.46ml | 1.542.12±498.97ml | <0.001 |

| Transfusion % | 19.3% | 35.9% | 0.042 |

| Packed red blood cells per patient | 0.37±0.77 | 0.98±1.77 | 0.014 |

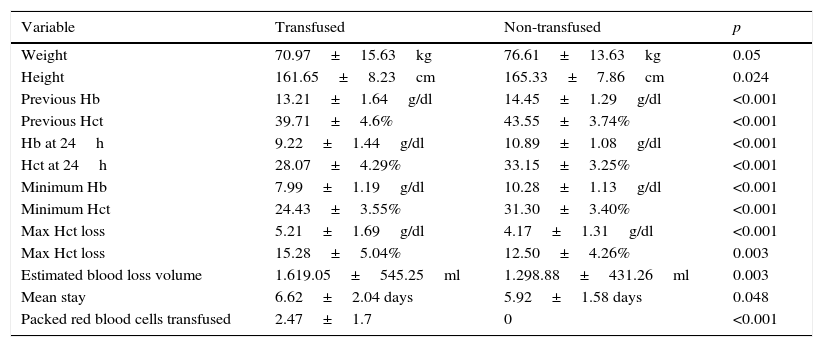

A second comparison was made, this time between the transfused patient group and the non-transfused group and no differences were found between them for the variables age, diagnosis, laterality, cardiovascular history and previous medication, type and size of stem, head, insert and acetabulum, reduction in haemoglobin levels and haematocrit in the first 24h compared to the earlier levels after the intervention and during the intervention.

The variables with significant differences between the transfused and non-transfused groups were weight, height, haemoglobin as well as haematocrit levels prior to the intervention, haemoglobin and haematocrit 24h after the operation, the lowest point during admission and maximum decrease in haemoglobin and haematocrit, estimated blood loss volume and number of red blood cell units transfused per patient (Table 5). The “sex” variable also showed significant differences between both groups (32.4% of transfused patients were male and 67.6% female, p<0.05). The mean hospital stay was longer in the transfused patient group (6.62±2.04 days vs 5.92±1.58 days, p<0.05).

Variables with significant differences between the group of transfused patients and the non-transfused patients.

| Variable | Transfused | Non-transfused | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight | 70.97±15.63kg | 76.61±13.63kg | 0.05 |

| Height | 161.65±8.23cm | 165.33±7.86cm | 0.024 |

| Previous Hb | 13.21±1.64g/dl | 14.45±1.29g/dl | <0.001 |

| Previous Hct | 39.71±4.6% | 43.55±3.74% | <0.001 |

| Hb at 24h | 9.22±1.44g/dl | 10.89±1.08g/dl | <0.001 |

| Hct at 24h | 28.07±4.29% | 33.15±3.25% | <0.001 |

| Minimum Hb | 7.99±1.19g/dl | 10.28±1.13g/dl | <0.001 |

| Minimum Hct | 24.43±3.55% | 31.30±3.40% | <0.001 |

| Max Hct loss | 5.21±1.69g/dl | 4.17±1.31g/dl | <0.001 |

| Max Hct loss | 15.28±5.04% | 12.50±4.26% | 0.003 |

| Estimated blood loss volume | 1.619.05±545.25ml | 1.298.88±431.26ml | 0.003 |

| Mean stay | 6.62±2.04 days | 5.92±1.58 days | 0.048 |

| Packed red blood cells transfused | 2.47±1.7 | 0 | <0.001 |

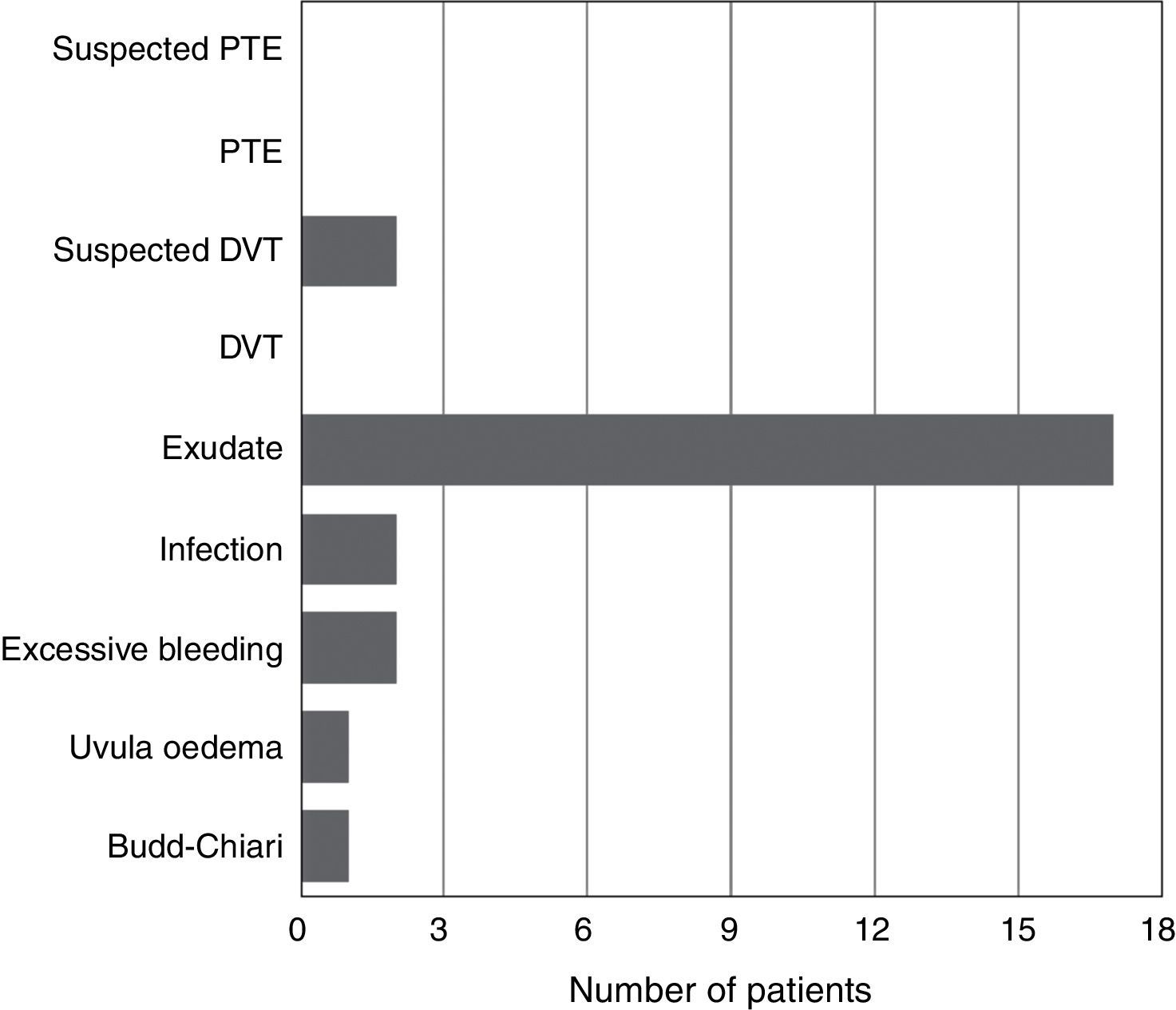

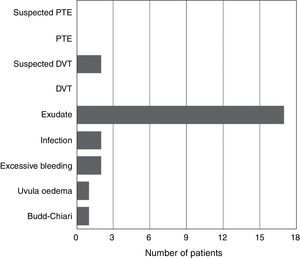

None of the patients presented symptoms compatible with pulmonary thromboembolism in any of the groups; 2 patients had symptoms compatible with deep vein thrombosis. There were significant differences between the groups studied with regard to complications (Fig. 2).

At the time of data collection 3 patients (2.5%) had died. All 3 belonged to the study group (tranexamic acid), although no significant differences were demonstrated in terms of “mortality” between the groups compared (tranexamic-control and transfused-non-transfused).

A logistic regression analysis was performed to study the relationship of different variables with the dependent “transfusion” variable. From the models proposed we conclude that there are 2 variables that notably influence the need for a transfusion: previous haemoglobin and estimated blood loss volume.

DiscussionInterest in the topical use of tranexamic acid has increased in recent years and the number of studies on the issue has multiplied. Alshryda13 is one of its pioneers, and raises the hypothesis that the systemic distribution of the drug when used intravenously might reduce the concentration in the target organ and also increase adverse effects. The dose of the drug is a point of debate in the different publications, although it seems to be effective and safe irrespective of the dose used. In our study we used 1.5g in 45ml physiological serum, which was an intermediate dose with regard to the doses that can be found in the references, is theoretically effective and was easy to distribute equally into the 3 amounts given during the operation. Another point of some controversy is the time that tranexamic acid should be used, although most papers support the idea that when it is used some time after completing the operation its effectiveness is reduced.21–23 Suction drainage was used in all the patients in to homogenise the sample.

Patients with history of cardiovascular disease or taking anticoagulant/antiplatelet medication were not excluded from the study because one of this paper's objectives was to check the cardiovascular safety of the drug. Wind et al. published a study where they used tranexamic acid topically rather than intravenously in these patients, without an increase in adverse effects or the incidence of complications.24 Furthermore, patients with increased thrombotic risk were not excluded from the CRASH-2 study performed on major trauma patients, and in the group using tranexamic acid a significant reduction in the risk of fatal and non fatal thrombotic events and the incidence of arterial thrombosis was observed.25,26

The study and control groups were comparable in terms of characteristics, except the “diagnosis” variable, which was distributed unequally between the 2 groups because the 6 patients with dysplasia formed part of the control group. Although in theory joint replacement surgery in a patient with dysplasia can be more complex, longer and carry the risk of greater bleeding, the fact is that no significant differences were demonstrated between the study group and the control group in surgery time or transfusion rates for the people with this condition (no significant differences were found on comparing the “diagnosis” variable in the transfused patient group with the non-transfused group).

Haemoglobin levels and haematocrit dropped lower in the test at 24h after the intervention in the tranexamic acid group than in the control group, and the lowest point reached during admission for both variables was also better in the tranexamic acid group. The mean difference in bleeding between the 2 groups was 325.37mL, this data was very similar to that published by other authors such as Yamasaki et al.27 and Yue et al.28 The patients in the control group required transfusion more often than the patients in the study group and also more red blood cell units per patient. Yue et al.28 obtained transfusion rates of 22.4% for the control group and 5.7% for the tranexamic acid group, March et al.29 had rates of 19.3% for the control group and 4.5% for the group with intravenous tranexamic acid, while Chang et al.30 achieved rates of 35% for the control group and 17% for the study group, these percentages were proportionally comparable with those of our paper. These differences observed in the transfusion rates between the different studies might be due to the transfusion criteria and protocols used in each centre. Although tranexamic acid appears to be a possible protective factor for transfusion, we could not demonstrate this in our study from a statistical point of view (RR=0.54; 95%CI: 0.29–0.99).

On comparing the transfused patient group with the non-transfused group, significant differences were found in terms of sex, weight and height between the groups. As a general rule, the male patients who were taller and heavier were less likely to be transfused. There were significant differences in haemoglobin and haematocrit levels before surgery as well, higher starting levels of these variables were associated with a lower need for transfusion; this fact has already been observed by authors such as March et al., in their study of 2013.29 There were also significant differences between the groups in haemoglobin levels and haematocrit at 24h after surgery, probably because these variables were used as the guideline for transfusing the patients. It is easy to think that the greater the blood loss during surgery, the more haemoglobin and haematocrit will reduce and therefore the higher the risk of transfusion, therefore there were also significant differences in minimum haemoglobin and haematocrit variables during admission, maximum drop in haemoglobin and haematocrit compared with the baseline levels and estimated blood volume between the transfused patient and the non-transfused patient groups.

There were no events compatible with pulmonary thromboembolism in any of the groups. Two patients in the tranexamic acid group had symptoms compatible with deep vein thrombosis, which could not be confirmed with Doppler ultrasound and both cases resolved spontaneously. There were 2 cases of early infection (one in the study group and the other in the control group) which were resolved with lavage, change of mobile parts and intravenous antibiotherapy for 2 weeks, followed by an oral regimen as outpatients. Two patients developed bleeding through the surgical wound which required angio CT scan and arteriography, without finding the cause of the bleeding, and which resolved spontaneously in both cases. Other complications were evenly distributed between the two groups and a higher incidence in the group with a cardiovascular history or anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet medication was not found.

The 3 patients who died belonged to the tranexamic acid group, although no significant differences were found between the groups for the “mortality” variable. None of the cases seemed to be clearly attributable to the use of tranexamic acid but rather to the patients’ personal histories: 2 patients died months after the intervention (one due to a longstanding idiopathic fibrosis and the other due to peritoneal carcinomatosis) and the other died 48h after the intervention following a Budd–Chiari syndrome, from a history of prostate carcinoma. This complication was described as a paraneoplastic syndrome and although a study from 2010 relates the onset of Budd–Chiari syndrome with a reduction in the body's fibrinolysis ability,31 there are no articles that directly relate this complication with the use of antifibrinolytic drugs.

There were no significant differences in mean hospital stay between the study and control groups, although there were between the transfused and non-transfused patient groups. Despite these differences, probably the clinical importance is small since there are no rigid criteria for patient discharge in our work centre, although there are several factors that have an influence (including social factors), not bleeding on its own.

Various logistic regression analysis models were used in the final part of the study to find the variables which most influenced the need for transfusion. The “haemoglobin prior to surgery” and “estimated blood loss volume” variables showed a strong correlation with a need for transfusion. The “randomisation” variable (belonging to the study group or to the control group) only showed significance with one of the models, although the correlation was very weak statistically; this might very probably be due to the small sample size. Although it was not possible to demonstrate a direct relationship between the 2 variables in the logistic regression, it seems clear that there are clinical and statistical differences between the tranexamic acid group and the control group that support the current references with regard to the use of topical tranexamic acid.

Limitations of the studyThe participation of different surgeons (although using the same surgical access approach) might have caused differences in the patients’ intraoperative bleeding. The level of experience of the surgeons was not the same and this might have influenced surgical trauma and the duration of the operation, although the differences in this regard were not studied.

Furthermore, calculating blood loss using a mathematical formula rather than measuring it directly might have over/underestimated the real bleeding. The formula used in this paper has a tendency to underestimate moderate loss (around 10% of total volume). Even so, it has been demonstrated in many studies to be an efficient method for estimating blood loss during surgery. The fact that the blood loss was directly measured in the surgical field, and collected in the drain, might have increased the study's precision in this regard, although much more complex methodologically.

The sample size was small to demonstrate statistically significant associations between some of the variables during the logistic regression analysis. Despite the fact that the number of patients analysed was included in the size calculated before the study and the loss less than estimated, it was not possible to demonstrate a direct relationship between the “use of topical tranexamic acid” and “need for transfusion” variables. Given the remaining results obtained in the study, it can be concluded that a larger sample size might demonstrate this relationship in a statistically significant way.

ConclusionsThe use of 1.5g of topical tranexamic acid diluted in 45ml physiological saline during cementless total hip arthroplasty using the Watson-Jones anterolateral approach resulted in less haemoglobin and haematocrit loss, a reduction in the need for transfusion and lower estimated blood loss, without increasing general complications or thromboembolic events (DVT and PTE), even in patients with cardiovascular histories or taking anticoagulant/antiplatelet drugs. Haemoglobin levels prior to surgery very significantly influence the need for transfusion, therefore it is essential for patients to undergo surgery in the best condition possible, from both a physical and from a blood test perspective. The mean hospital stay does not seem to be significantly affected by the use of topical tranexamic acid. Based on these results, we have started to use topical tranexamic acid as part of our centre's hip arthroscopy protocol.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence I.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the research was carried out according to the ethical standards set by the responsible human experimentation committee, the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their centre of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Tavares Sánchez-Monge FJ, Aguado Maestro I, Bañuelos Díaz A, Martín Ferrero MÁ, García Alonso MF. Eficacia y seguridad de la aplicación del ácido tranexámico tópico en la artroplastia primaria no cementada de cadera: estudio prospectivo, aleatorizado, doble ciego y controlado. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2018;62:47–54.