Posterior lumbar screw fixation is a common surgical procedure nowadays. However, it can sometimes produce complications that can be devastating. One of the less common causes of major complication is the misplacement of a pedicle screw. This highlights the importance of being methodical when placing pedicle screws, and checking that the pathway has been created correctly and their placement.

We present a case of a massive bleed after a pedicular screw placement during lumbar canal stenosis surgery. Screw malposition led to intraoperative haemodynamic instability after failed attempts to control bleeding in the surgical site. Contrast enhanced CT imaging revealed a lumbar intersegmentary artery injury that was eventually controlled by means of a coil embolisation.

La fusión instrumentada lumbar por vía posterior se realiza de manera habitual hoy en día, aunque en algunas ocasiones puede inducir complicaciones que pueden llegar a ser devastadoras. Una de las causas, aunque poco frecuentes, de complicación mayor es la malposición de los tornillos pediculares, de ahí la importancia de ser metódicos a la hora de su colocación, comprobando el correcto labrado del trayecto y su introducción.

Presentamos un caso de sangrado masivo tras la introducción de un tornillo pedicular lumbar durante una cirugía por estenosis de canal. La malposición del tornillo conllevó la inestabilidad hemodinámica intraoperatoria de la paciente tras el fracaso de los métodos habituales de control de sangrado en el campo quirúrgico. La realización de una TAC con contraste evidenció lesión de la arteria intersegmentaria lumbar que fue finalmente controlada mediante embolización e implantación de coil vascular.

Degenerative lumbar surgery has increased in the past 20 years and specialist units in the treatment of spine disorders have been created over this time. Despite the prevalence of this type of surgery and the experience of surgical teams, the procedures are not free from complications.

Bleeding from the surgical field is usually associated in these operations with dissection of the epidural vessels during the procedure to release and decompress the spinal canal. Pedicle screw instrumentation offers better grip of fixation and fusion rates, but has involved an associated risk of injury to the neurovascular structures.1,2 Large-vessel vascular injury is rare in this type of surgery, and in most cases is secondary to mechanical aggression during the procedure.3 If it does occur, it can be resolved by laparotomy and repair of the bleeding vessel, or by peripheral embolisation.3–5 There are few cases in the literature, and none specific to injury of a segmental artery due to malposition or a defect in the lumbar pedicle screw pathway.

We present the case of an extensive arterial bleed after preparation of a lumbar pedicle screw secondary to laceration of the L5 lumbar artery and its therapeutic management by arteriography and embolisation.

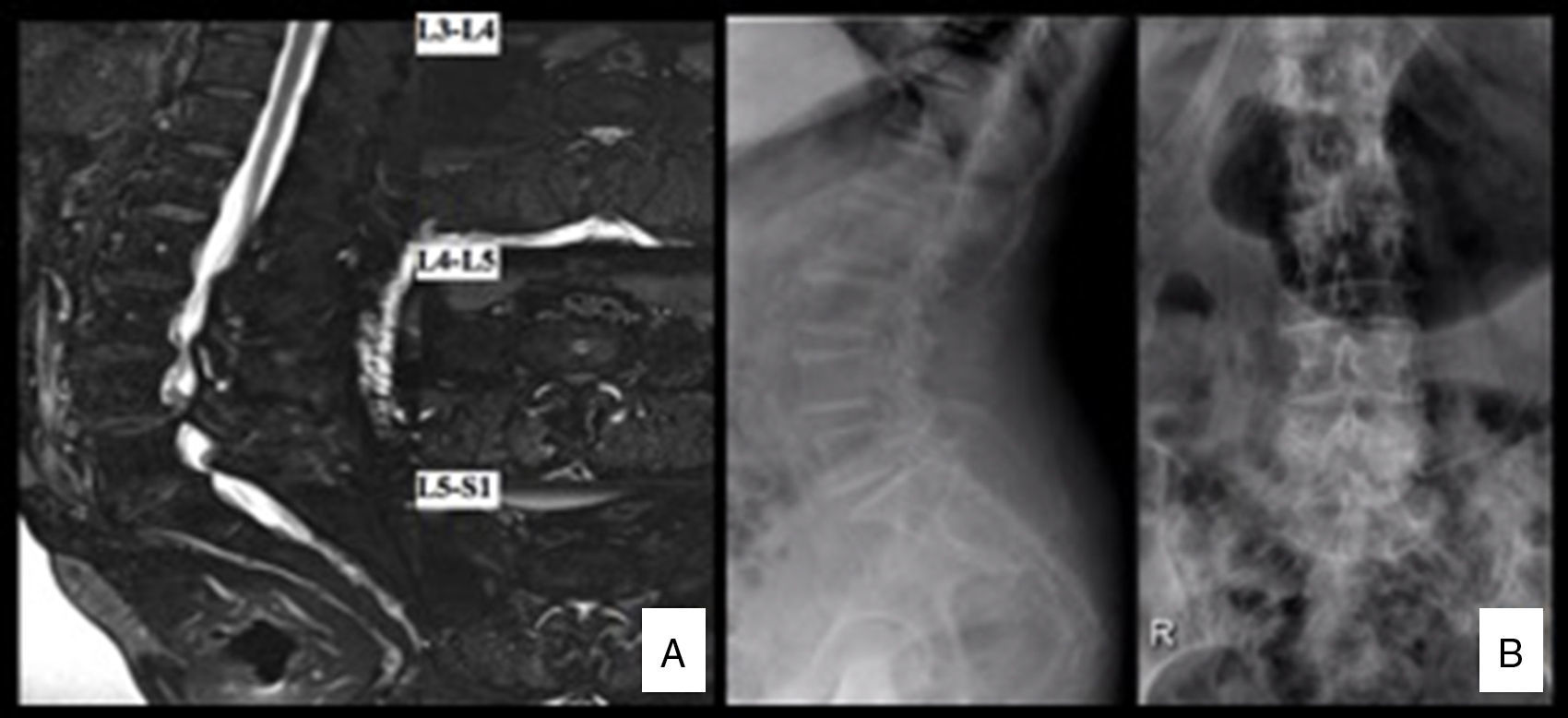

Clinical caseWe present the case of a 77-year-old woman who underwent elective decompressive lumbar surgery and posterolateral L3-S1 fusion secondary to stenosis of the lumbar canal (Fig. 1A,B), with no contraindications to anaesthesia, and ASA II-III. The surgery progressed without incident until one of the pedicle screws was introduced; we detail what followed below.

(A) Anteroposterior and lateral radiography of the lumbar spine showing interapophyseal degenerative changes of the L5-S1 space, and degenerative listhesis L4–L5. (B) MRI scan of the lumbar spine: major stenosis of the spine at three levels, essentially at level L4-L5 due to disc bulging, interapophyseal degenerative changes and hypertrophy of the yellow ligament.

Anaesthetic induction and intubation took place with no complications. A bolus of 10mg/kg tranexamic acid (Amchafibrin® 500mg) was administered over 20minutes prior to the operation, followed by intravenous perfusion of 2mg/kg/h until the end of the procedure. Blood pressure was strictly monitored and a mean 90mmHg maintained, the patient was placed in the prone position on a radiotransparent table in the knee-chest position (all fours) position with a roller below the chest and two cushioned rollers supporting the iliac crests, leaving the abdomen free from pressure. The operation was performed by an orthopaedic assistant surgeon with more than 10 years experience in spinal surgery and assisted by a third-year resident.

A standard posterior lumbar midline approach was used and dissection in layers followed by central decompression with release of the bilateral foramen without associated discectomy. Then the pedicle screws were placed in L3 to S1 on the left side, without complications, as were the pedicle screws L3 and L4 on the right side. The right pedicle was prepared in the standard way, selecting the insertion point at the confluence of the transverse process with the upper facet of the vertebra (Magerl's insertion point). The pathway was started with the Steffee device, checking that the pathway had been correctly created with the palpation probe. As is usual, a starting tap of 5.5 was passed and the integrity of the four pedicle walls checked again with the palpation probe. Then a screw of 6.5mm by 40mm was selected for insertion. The pedicle screw did not appear to gain purchase correctly as it was introduced; therefore it was removed for checking. After removing the pedicle screw, bright red bleeding started from the region of the lateral edge of the vertebral body, deeper than the level of the transverse process. We attempted to establish the source of the bleeding with suction and bipolar coagulation. The bleeding continued despite the first attempts at coagulating the bleeding vessel, which we could not identify. We then decided to apply plugging and applied 8ml of haemostatic gel (Surgiflo®), packing with gauze and irrigation with warm saline. Because the bleeding did not stop, a further attempt was made to locate the bleeding point, but it was impossible to reach due to the difficulty in dissecting the anterior part of the vertebra from the posterolateral region with such extensive bleeding. Three-four minutes after the onset of the acute haemorrhage the patient started to become haemodynamically unstable. The anaesthetics team started volume replacement therapy with a massive transfusion protocol with volume infusion of saline and colloids.

The pillows at the iliac crests were removed to reduce pressure on the iliac vessels. Local posterolateral packing was placed. We decided to obtain mechanical stability of the operation rapidly. The right S1 pedicle screw was inserted, the rods contoured to lordosis were rapidly placed and the packing was removed just before closing, checking that the bleeding had partially abated. After adding an intertransverse autogenous graft and placing a deep drain, the wound was closed as quickly as possible. Meanwhile, the interventional radiologist was informed to perform a diagnostic-therapeutic arteriography due to suspected injury to the lumbar segmental artery.

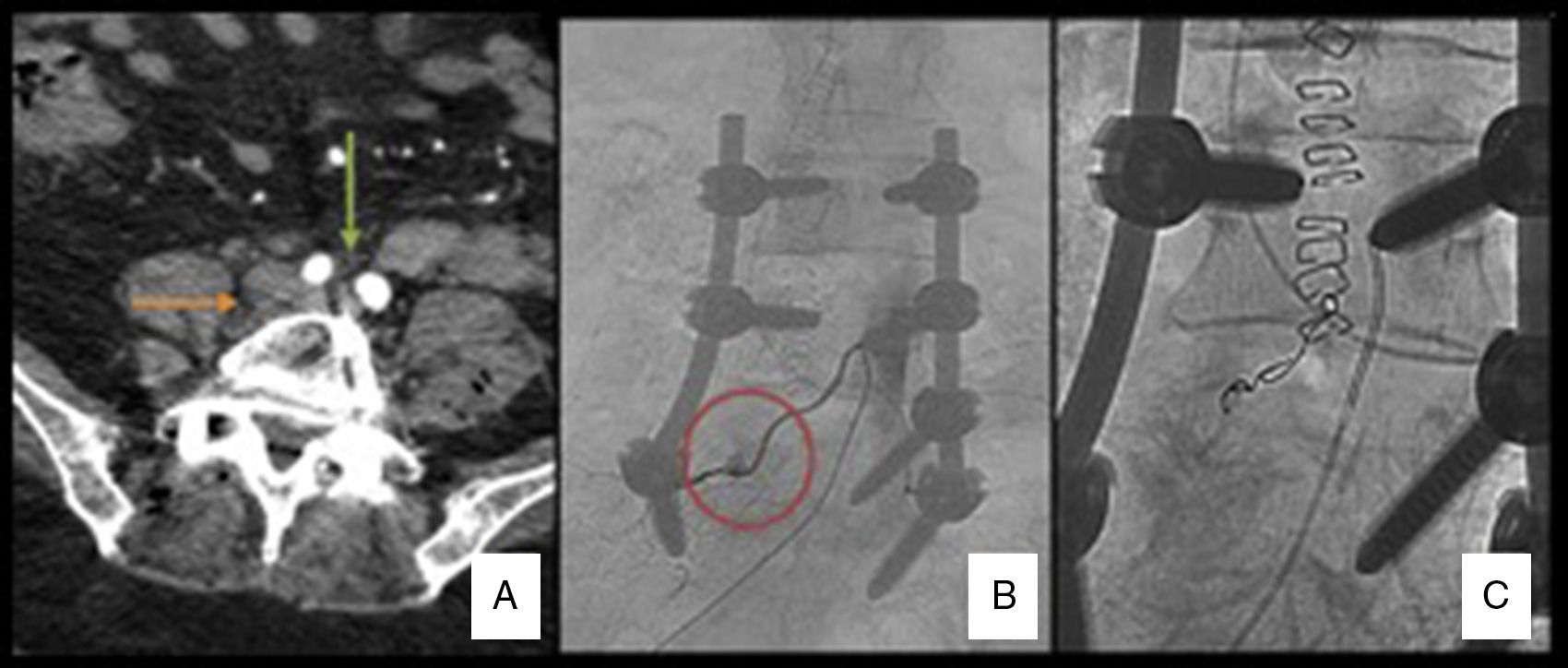

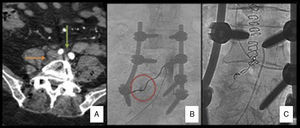

After placing the patient in the supine position, she became unstable again. Her blood pressure dropped to 37mm Hg for 3–5min, requiring dopamine, crystalloids and fluids to stabilise her. Resuscitation manoeuvres were not necessary. After the patient had been stabilised, she was transferred to X-ray under monitoring where under the instructions of the interventional radiologist she underwent an angio-CAT scan which ruled out bleeding from the large vessels or active intra-abdominal bleeding; only a haematoma was observed suggesting active bleeding in the right lumbar paravertebral region (Fig. 2A). Once large-vessel bleeding had been discounted, selective arteriography was performed through the right common femoral artery with a cobra type catheter, performing retrograde catheterisation until reaching the right L5 lumbar artery. A pseudoaneurysmatic lesion was revealed after the introduction of contrast with active extravasation of the contrast medium from the right L5 lumbar artery (Fig. 2B). This pseudoaneurysm was then embolised with 300–500μm microspheres and then 3×3 microcoils. A further contrast injection confirmed that the extravasation of contrast had stopped at the level of the pseudoaneurysm and, therefore, the bleeding had stopped (Fig. 2C). From the start of the bleed until it was stabilised by embolisation the patient required vasoactive drugs and a transfusion of 5 units of red cell concentrate, 700ml of fresh plasma, 1g fibrinogen, 1000cc colloids and 2500 crystalloids.

(A) Abdominal CAT with contrast; slice at the level of the L5 vertebral body L5. Green arrow: iliac arteries with contrast. Orange arrow: right paravertebral haematoma. (B) Arteriography: extravasation of contrast at the level of the right L5 lumbar artery suggestive of pseudoaneurysm. (C) Postembolisation arteriography: microcoils can be observed in the root of the L5 lumbar artery without the passage of contrast.

The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for monitoring. Two days later, following stabilisation of haemodynamics and analytical tests, the patient was discharged to the main ward, where she started sitting and assisted walking on the fourth postoperative day. All the analytical, clinical and radiographic checks were satisfactory, and therefore the patient was discharged on the seventh postoperative day. Follow-up check at one year after surgery was satisfactory with clinical improvement of the preoperative symptoms. There were no complications after the vascular repair.

DiscussionDespite the routine nature of degenerative lumbar surgery in adults and the experience of surgical teams in this common scenario, complications can arise that endanger the life of the patient. The importance of reporting a clinical case in this paper is to show the different alternatives for solving intraoperative complications to enable us to react appropriately should encounter such a situation in the future.

In general, good anaesthetic control is essential for all spinal surgery general, to reduce the risk of bleeding with measures such as appropriate muscle relaxation, control of blood pressure and the use of antifibrinolytic agents. The patient should be positioned so as to leave the abdomen free and not compress the epidural venous plexus and reduce pressure on Batson's venous plexus. Supports should prevent compression of the vascular structures, essentially the iliac vessels in the inguinal area.

The usual sources of bleeding in degenerative, lumbar decompression surgery with instrumented fusion are from the epidural vessels during foraminotomy or discectomy, or from the vertebral body during canalisation of the pedicle. Damage to a large vascular structure is very rare. Most published cases of vascular injury occurred during an intervention on L4-L5 or L5-S1, due to the proximity of the ventral area of the aortic bifurcation in the iliac arteries. The right and left common iliac arteries are usually located anterior to the vertebral body of L4 or disc space L4-L5 in 90% of cases. At this level, the inferior vena cava is located between the disc and the right iliac artery or both common iliac arteries.6 Most of the vascular injuries described were caused during discectomy,6–8 when the work instruments go over the safe line marked by the anterior longitudinal ligament. Ganesan et al.9 published a study on the effect of positioning the patient and the distance from the intervertebral spaces L4-L5 and L5-S1 to the common iliac vessels. In the supine position, the distance to the iliac vessels is less than 5mm from the anterior face of the disc space in the lower lumbar area, especial at level L4-L5. These relationships are not very different in the prone position, and even the attempt to decompress the abdominal content positioning the patient with crest supports did not distance the retroperitoneal vessels from the vertebral column.

Traditionally, bleeding from a large vessel should be approached via exploratory laparotomy to locate the point of bleeding.3 This enables repair of the injury by direct suture or with autologous or synthetic vein patches.5 However, these operations are not free from risk and increase global morbidity and mortality of the surgical process.4,5,10 Another therapeutic option in the case of non-embolisable large-vessel injuries is the placement of endoprostheses with endovascular techniques commonly performed by vascular surgeons,5 which reduces the potential comorbidity of open techniques. It must be borne in mind that positioning patients prone during surgery can cause some vascular compression and as such can temporarily block some vascular injuries which can cause a worsening of the haemodynamic situation of the patient when they go to the supine position, as in our case. In these circumstances, an intraoperative, diagnostic and therapeutic arteriography was suggested.8 The literature describes a recent case of arterial injury that was intraoperatively embolised by popliteal catheterisation.4 There are several studies about the incidence, aetiology and location of the vascular lesions associated with anterior approach spinal surgery; however, vascular lesions through posterior approaches are less common, and we found no studies in the literature on the incidence of these types of lesions.

In our patient, the injury was caused during insertion of the screw into a pedicle channel that had been correctly created beforehand. Our hypothesis is that probably the screw did not follow the probed pathway causing a problem of non convergence that might have caused the pedicle to rupture or even invade the region of the lumbar region when it came out of it. It is essential to emphasise the importance of checking the integrity of the pedicle with a probe every time we complete a gesture with the Steffee device, or the tap. The integrity of the four walls of the pedicle channel must be checked and if there is any gap, the screw should not be placed because of the risk that would entail. Although with all these precautions, given that most screws are self-tapping, there is always the risk that when they are introduced they might take the wrong route or there could be incorrect convergence and injuries caused. Misplacement of pedicle screws can cause damage to the nerve structure if we invade the canal, and organic structures if we invade the retroperitoneum.1,2

A failure in inserting the screw can have several causes. Under-tapping the channel can mean that when the screw is inserted the diameter is large and it does not pass through correctly. It can be that the force applied at the screwdriver handle is not realised in the axis in the direction of the probing, and creates a faulty track as the screw is inserted. Even so, no surgery is complication-free, despite checking the pedicle channel beforehand and the experience of the surgeon in this type of surgery. This experience alerted our team when they felt that the screw was not gripping correctly.

In the event of a bleed, first local haemostasis should be achieved, the area of active bleeding located and cauterised with the cautery knife. If we cannot find the bleeding vessel, either due to difficulties in dissection or poor visualisation, the area should be packed with gauze or dressings, and if this is not sufficient haemostatic matrices can be applied. Removing the iliac crest supports can reduce the pressure on the iliac arteries, and help to reduce the haemorrhage, we must be prepared for treatment alternatives.

In our case, because we located the bleeding in the anterolateral area of the vertebral body, we thought at first that there was injury to the lumbar segmental artery. There are five pairs of lumbar arteries (left and right). The first four pairs are direct branches of the abdominal aorta and the fifth pair forms the branch of the middle sacral artery, which is also a branch of the abdominal aorta. They run from their anterior origin lateroposteriorly, passing posterior to the sympathetic trunk and penetrate below the medial arcuate ligament and when they reach the neural foramen, divide into two branches: dorsospinal and abdominal. They irrigate the abdominal wall, the vertebrae and lumbar muscles. An abdominal approach would not have enabled the injury to be easily identified because of the depth of its anatomical location. For this reason embolisation was considered the best option to locate and treat the point of bleeding. The process was accelerated by anticipating the need for arteriography, and alerting the interventional radiologist of the situation as we brought the operation to an end. The anaesthetists kept the patient haemodynamically stable enabling her to be transferred to radiology for CAT scan and arteriography.

If it is not possible to maintain the patient's haemodynamic stability and they cannot be transferred to radiology, an exploratory laparotomy or intraoperative arteriography is possible.

To conclude, surgery of lumbar pain and fixation with pedicle screws is a very common, effective and safe procedure at present. Even in the hands of an expert surgeon, there can be complications with this type of surgery due to the anatomical hazards in this location. Vascular damage must be considered if there is uncontrollable bleeding on insertion of the screws. It is important to be aware of this type of complication and how to act to combat it in future operations, and to acknowledge the coadjuvant role of interventional radiology.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that neither human nor animal testing have been carried out under this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have complied with their work centre protocols for the publication of patient data.

Privacy rights and informed consentThe authors declare that no patients’ data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To Dr. Enrique Izquierdo, for his dedication and for instilling all those around him with a thirst for knowledge.

Please cite this article as: Álvarez Postigo M, Pizones Arce J, Izquierdo Núñez E. Pseudoaneurisma de arteria segmentaria lumbar tras introducción de tornillo transpedicular L5. Una rara complicación vascular. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:436–440.