Due to its high prevalence and serious consequences it is very important to be well aware of factors that might be related to medical complications, mortality, hospital stay and functional recovery in elderly patients with hip fracture.

Material and methodsA prospective study of a group of 130 patients aged over 75 years admitted for osteoporotic hip fracture. Their medical records, physical and cognitive status prior to the fall, fracture type and surgical treatment, medical complications and functional and social evolution after hospitalisation were evaluated.

ResultsPatients with greater physical disability, more severe cognitive impairment and those who lived in a nursing home before the fracture had worse functional recovery after surgery. Treatment with intravenous iron to reduce transfusions reduced hospital stay and improved walking ability. Infections and heart failure were the most frequent medical complications and were related to a longer hospital stay. The prescription of nutritional supplements for the patients with real indication improved their physical recovery after the hip fracture.

ConclusionsEvaluation of physical, cognitive and social status prior to hip fracture should be the basis of an individual treatment plan because of its great prognostic value. Multidisciplinary teams with continuous monitoring of medical problems should prevent and treat complications as soon as possible. Intravenous iron and specific nutritional supplements can improve functional recovery six months after hip fracture.

Analizar las características de los pacientes ingresados por fractura de cadera y su evolución 6 meses tras la cirugía para determinar los factores potencialmente relacionados con estancia hospitalaria, complicaciones médicas, mortalidad y recuperación funcional tras esta enfermedad tan prevalente y con graves consecuencias.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo de un grupo de 130 pacientes mayores de 75 años hospitalizados por fractura de cadera de perfil osteoporótico. Se evaluaron sus antecedentes médicos, situación mental y física previas a la caída, tipos de fractura y tratamiento quirúrgico, complicaciones hospitalarias, así como evolución funcional y social tras la hospitalización.

ResultadosLos pacientes que tenían mayor grado de deterioro físico y mental previamente a la fractura y los institucionalizados tuvieron peor capacidad de recuperación tras la cirugía. El empleo de terapias alternativas a la transfusión para el tratamiento de la anemia se relacionó con disminución de estancia hospitalaria y mejor capacidad de deambulación a medio plazo. Las principales complicaciones médicas en el ingreso fueron infección e insuficiencia cardiaca, e implicaron prolongación de la hospitalización. La prescripción de suplementos nutricionales en pacientes adecuadamente seleccionados se relacionó con mejor evolución funcional.

ConclusionesLa valoración de la situación mental, física y social previas a la fractura debe ser la base de un plan de tratamiento individualizado por ser claramente determinante de pronóstico. Los equipos multidisciplinares con seguimiento médico continuado simultáneo al quirúrgico son importantes para prevenir y tratar precozmente las frecuentes complicaciones perioperatorias. La administración de ferroterapia intravenosa y la prescripción de suplementos de nutrición pueden mejorar la recuperación física a medio plazo del paciente intervenido fractura de cadera.

Hip fractures in elderly patients are important because of their high prevalence, serious associated functional deterioration and the high costs they entail. Patients with hip fractures often have many comorbidities, dementia and/or functional deterioration prior to the fracture and frequently have medical complications during their hospital stay. Multidisciplinary medical and surgical treatment is associated with fewer complications, lower mortality and better prognosis.1 The professionals in orthogeriatric teams have a common interest in identifying factors that will potentially result in a favourable outcome for patients who undergo intervention.

The objective of this study was to analyse the clinical features of elderly patients admitted after a hip fracture, their outcome and treatment after surgical admission to determine the parameters relating to mortality, functional recovery and hospital stay. The aim was to individualise care plans and identify the therapeutic measures that might improve outcomes. It was considered of particular interest to evaluate how the recovery of these frail patients was influenced by a systematic nutritional approach and by treating anaemia with complementary therapies to transfusion.

Material and methodsStudy designAn observational prospective study of the medical and surgical features of 130 patients aged over 75 admitted consecutively after proximal fracture of femur to the orthopaedics department of the University Hospital of Guadalajara between the months of November 2014 and June 2015. All of the patients were assessed on admission and treated by the geriatric team on a daily basis during their hospital stay. Progress was monitored on discharge, and at 3 and 6 months after the fracture.

The medical treatment of elderly hip fracture patients is protocolised and based on recent literature.2 According to this protocol, patients with a haemoglobin lower than 11g/dl received treatment with intravenous ferrotherapy (400mg iron sucrose and 30,000IU of epoetin alfa as a single dose on admission) and those with haemoglobin below 8.5g/dl were given a transfusion. Daily analyses were taken in the peri-operative period and postoperative days 1, 2 and 4, unless there were complications. Treatment with nutritional supplements was indicated on discharge for the patients with hypoproteinaemia (total proteins under 60g/l and/or albumin under 35g/l) and cholesterol below 150mg/dl in the analysis on admission and/or very reduced intake during their hospital stay. The patients were supplemented with 250kcal and 10g protein per day during the first 3 months, and from 3 to 6 months for those whose analyses continued to show signs of malnutrition.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaAll patients with proximal fracture of femur with an osteoporotic profile and older than 75 years of age who were capable of understanding and completing the informed consent form or who had a legal representative to do so were included in the study. Patients with pathological fractures, or high impact trauma fractures, those with iron deposit disorders, intolerant to ferrotherapy or in whom erythropoietin was contraindicated were excluded.

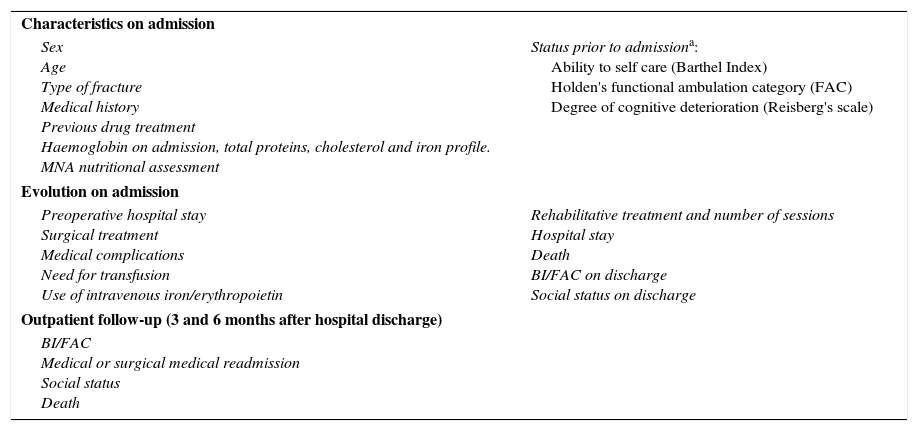

Data collection and description of variablesThe information was gathered from the hospital's electronic clinical histories and the assessment by the geriatrics researchers in the first 3 days after the fracture. A first assessment took place on admission to hospital and then at 3 and 6 months by telephone to the patients’ home. Table 1 shows the parameters assessed.

Parameters assessed.

| Characteristics on admission | |

| Sex Age Type of fracture Medical history Previous drug treatment Haemoglobin on admission, total proteins, cholesterol and iron profile. MNA nutritional assessment | Status prior to admissiona: Ability to self care (Barthel Index) Holden's functional ambulation category (FAC) Degree of cognitive deterioration (Reisberg's scale) |

| Evolution on admission | |

| Preoperative hospital stay Surgical treatment Medical complications Need for transfusion Use of intravenous iron/erythropoietin | Rehabilitative treatment and number of sessions Hospital stay Death BI/FAC on discharge Social status on discharge |

| Outpatient follow-up (3 and 6 months after hospital discharge) | |

| BI/FAC Medical or surgical medical readmission Social status Death | |

Functional and mental capacity were assessed before and after surgery by means of validated scales. The Barthel Index (BI)3 was used to assess self-care ability, using a score from 0 (total physical dependence and immobility) to 100 (complete independence for ambulation and self-care). Holden's scale4 was used to assess ambulation ability, which ranges from 0 (completely immobilised patient) to 5 points (independent ambulation, including stairs). The level of cognitive impairment was described using Reisberg's scale (GDS),5 from 1 (no cognitive deterioration) to 7 points (severe dementia). The Mini Nutritional Assessment Test (MNA)6 was used to assess risk of malnutrition. This classifies the patients into 3 groups according to the score achieved in a simple survey on nutritional habits and anthropometric characteristics (>24 points well-nourished; between 17 and 24 points a risk of malnutrition and more than 24 points satisfactory nutritional condition). This clinical evaluation was complemented with an analytical assessment of protein and fats.

Statistical analysisIn the descriptive statistical study, the continuous variables were expressed by the median and interquartile interval and the categorical variables in percentages. A univariate statistical study was carried out initially. The chi-square test was used for comparison between variables, and Fisher's exact test when appropriate. To compare between the means of the continuous variables, when the values adapted to normal distribution, the Student's t-test was used, and variance or linear regression analysis. In the event of strong asymmetry or lack of normality, non parametric tests were used. The significant variables in the univariate analysis were entered into a stepwise backward linear regression or multiple logistics model. A p value below .05 was considered statistically significant

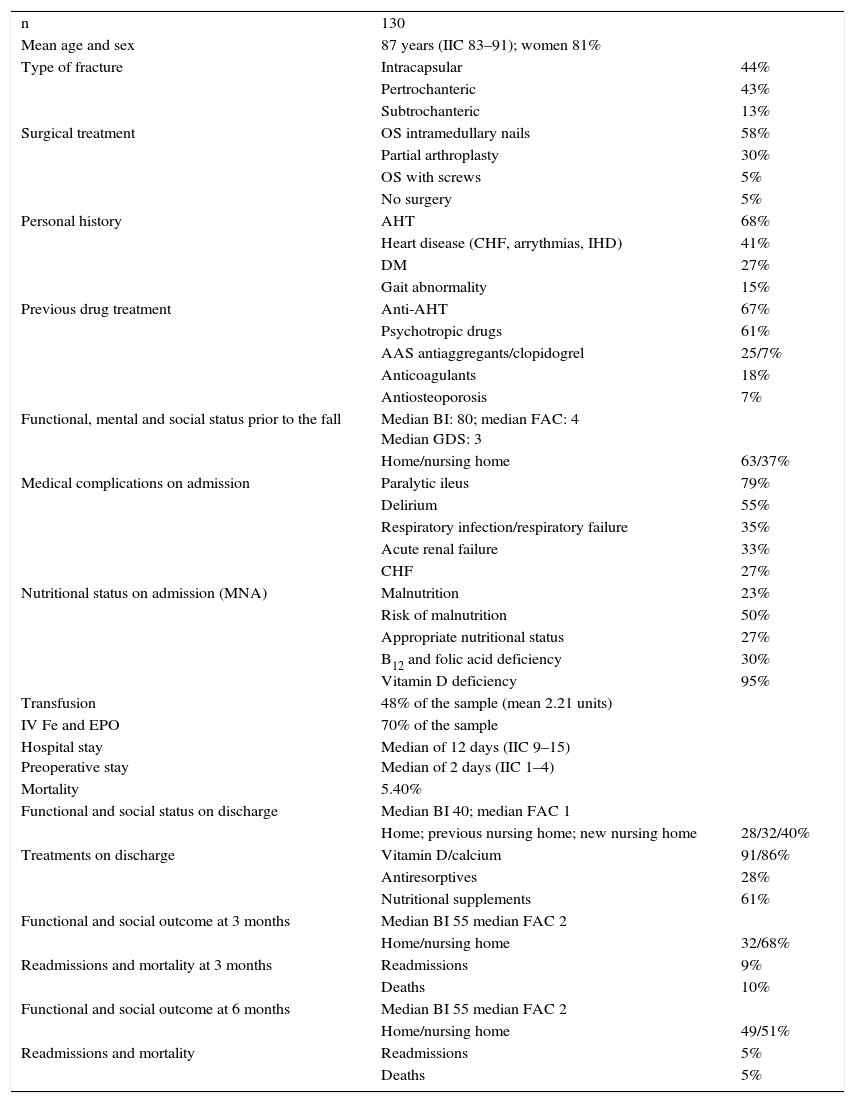

ResultsSample characteristicsThe patient's characteristics, hospital treatment and their physical and social progress on admission and over the 6 subsequent months are described in Table 2.

Patients’ characteristics and outcome.

| n | 130 | |

| Mean age and sex | 87 years (IIC 83–91); women 81% | |

| Type of fracture | Intracapsular | 44% |

| Pertrochanteric | 43% | |

| Subtrochanteric | 13% | |

| Surgical treatment | OS intramedullary nails | 58% |

| Partial arthroplasty | 30% | |

| OS with screws | 5% | |

| No surgery | 5% | |

| Personal history | AHT | 68% |

| Heart disease (CHF, arrythmias, IHD) | 41% | |

| DM | 27% | |

| Gait abnormality | 15% | |

| Previous drug treatment | Anti-AHT | 67% |

| Psychotropic drugs | 61% | |

| AAS antiaggregants/clopidogrel | 25/7% | |

| Anticoagulants | 18% | |

| Antiosteoporosis | 7% | |

| Functional, mental and social status prior to the fall | Median BI: 80; median FAC: 4 Median GDS: 3 | |

| Home/nursing home | 63/37% | |

| Medical complications on admission | Paralytic ileus | 79% |

| Delirium | 55% | |

| Respiratory infection/respiratory failure | 35% | |

| Acute renal failure | 33% | |

| CHF | 27% | |

| Nutritional status on admission (MNA) | Malnutrition | 23% |

| Risk of malnutrition | 50% | |

| Appropriate nutritional status | 27% | |

| B12 and folic acid deficiency | 30% | |

| Vitamin D deficiency | 95% | |

| Transfusion | 48% of the sample (mean 2.21 units) | |

| IV Fe and EPO | 70% of the sample | |

| Hospital stay Preoperative stay | Median of 12 days (IIC 9–15) Median of 2 days (IIC 1–4) | |

| Mortality | 5.40% | |

| Functional and social status on discharge | Median BI 40; median FAC 1 | |

| Home; previous nursing home; new nursing home | 28/32/40% | |

| Treatments on discharge | Vitamin D/calcium | 91/86% |

| Antiresorptives | 28% | |

| Nutritional supplements | 61% | |

| Functional and social outcome at 3 months | Median BI 55 median FAC 2 | |

| Home/nursing home | 32/68% | |

| Readmissions and mortality at 3 months | Readmissions | 9% |

| Deaths | 10% | |

| Functional and social outcome at 6 months | Median BI 55 median FAC 2 | |

| Home/nursing home | 49/51% | |

| Readmissions and mortality | Readmissions | 5% |

| Deaths | 5% |

The relationship with age, history and medical complications, types of fracture and surgical treatment with functional outcomes after discharge are described later.

All the cases that were not operated were irreversibly immobile.

The patients that came from care homes were less able to walk and care for themselves, and were more mentally impaired than those that came from their own homes (p<.05). Moreover, the hospital stay of those who had been institutionalised was shorter (10.5 vs 12.6 days from home, p<0.005). At time of discharge their BI was poorer as well (p<0.005). The patients who required temporary care in a care home on discharge were functionally better than those who came from their home. Fifteen percent of those who lived at home beforehand were still in an institution 6 months after their fracture.

The rehabilitation department was asked to assess all the patients who were not completely immobile previously and whose surgical outcomes allowed post-operative weight bearing. Seventy eight percent of the patients received rehabilitation treatment, a mean of 4 physiotherapy sessions during their hospital stay. More of the patients who were in a better physical and mental situation before surgery (p<0.05) and those who came from their own homes (own home 73% vs care home 27%; p<.005; OR: .14; 95%CI: .05–.37) received physiotherapy treatment.

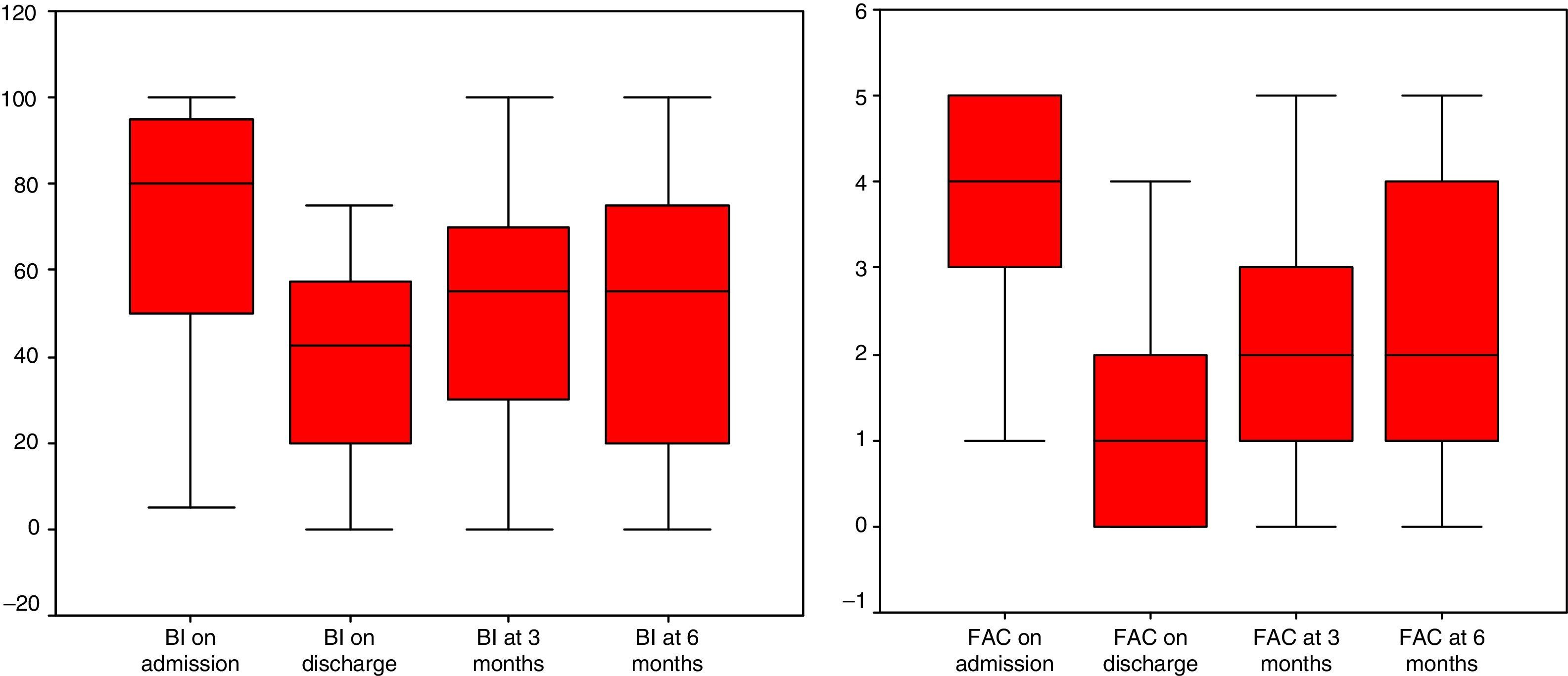

Fig. 1 shows the patients’ progress in ability to walk and perform self-care from prior to admission to time of discharge, and their improvement over the 3 months following the fracture. Their functional capacity remained stable between 3 and 6 months after discharge from hospital, but the initial improvement did not increase.

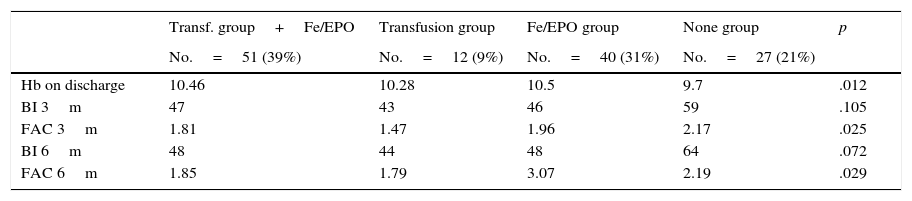

Influence of the type of anaemia treatment on functional outcome in the medium termThe characteristics of the patients’ outcomes according to the type of anaemia treatment indicated are shown in Table 3.

Effects on physical outcome of the different types of anaemia treatment.

| Transf. group+Fe/EPO | Transfusion group | Fe/EPO group | None group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No.=51 (39%) | No.=12 (9%) | No.=40 (31%) | No.=27 (21%) | ||

| Hb on discharge | 10.46 | 10.28 | 10.5 | 9.7 | .012 |

| BI 3m | 47 | 43 | 46 | 59 | .105 |

| FAC 3m | 1.81 | 1.47 | 1.96 | 2.17 | .025 |

| BI 6m | 48 | 44 | 48 | 64 | .072 |

| FAC 6m | 1.85 | 1.79 | 3.07 | 2.19 | .029 |

Forty-eight percent of the patients underwent blood transfusion (an average 2.2 units). The need for transfusion of blood products was not associated with increased complications or mortality on admission. The hospital stay of the transfused patients was 1.7 days longer than those who were not (p<.005, MD CI: .07–3.29). Three months after the fracture the ability to walk of those who had undergone a transfusion was poorer than those who had not, and this difference was maintained at 6 months. In the 6 months of follow-up after the fracture a transfusion was not associated with mortality or readmission.

Seventy percent of the patients received intravenous ferrotherapy and erythropoietin (FE/EPO). This treatment was associated with better medium term walking ability (FAC 3–6 months). Self-care ability was also better in the non-transfused patients with a near statistically significant difference at 3 and 6 months. The functional recover of the group of patients that received transfusion and intravenous ferrotherapy was better than those who only received a transfusion. The patients who did not require anaemia treatment on admission also had a better outcome at 6 months than the transfused patients, although with a slightly lower haemoglobin on discharge.

Influence of nutritional treatment on mid-term functional prognosisSeventy-five percent of the patients showed signs of malnutrition or risk according to the MNA test. The malnourished patients had poorer functional ability and greater previous mental impairment (p<.005) and most often came from a care home. Likewise, compromised nutritional status was associated with a greater need for transfusion on admission and poorer subsequent functional evolution in the univariate analysis (p<.005).

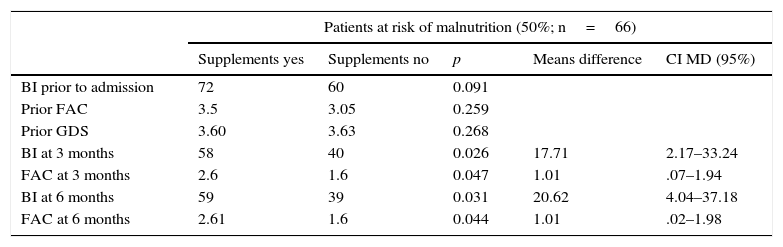

Seventy percent of the patients with an MNA test score below 24 (indicator of malnutrition or risk) and 45% of patients with a normal MNA due to poor intake were receiving treatment with nutritional supplements on discharge. On examining the effect of nutritional supplements on the development of functional ability, relevant differences were found in the group at risk of malnutrition, indicating the efficacy of this treatment. Its prescription in this group was associated with better functional recovery measured by both BI and FAC, and the previous situation was comparable (Table 4).

Functional outcome of the patients at risk of malnutrition (MNA score between 17 and 24 points) according to treatment with protein calorie supplements.

| Patients at risk of malnutrition (50%; n=66) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplements yes | Supplements no | p | Means difference | CI MD (95%) | |

| BI prior to admission | 72 | 60 | 0.091 | ||

| Prior FAC | 3.5 | 3.05 | 0.259 | ||

| Prior GDS | 3.60 | 3.63 | 0.268 | ||

| BI at 3 months | 58 | 40 | 0.026 | 17.71 | 2.17–33.24 |

| FAC at 3 months | 2.6 | 1.6 | 0.047 | 1.01 | .07–1.94 |

| BI at 6 months | 59 | 39 | 0.031 | 20.62 | 4.04–37.18 |

| FAC at 6 months | 2.61 | 1.6 | 0.044 | 1.01 | .02–1.98 |

The patients who waited for surgery for longer, the transfused patients, those who had infectious or cardiorespiratory complications and those who needed to return to a care home after discharge spent more days in hospital (p<0.05 in the univariate analysis). Delirium was not associated with prolonged hospital stay. In the multivariate analysis, a longer preoperative stay and cardiological complications showed an independent association with more days of admission. Suffering heart failure on admission lengthened hospital stay by more than 4 days (β 4.16 95% CI β 2.5–5).

Determining factors of mortality on admissionSeven patients died on admission (5.4%). In the univariate analysis the only factors that were significantly associated with mortality were complications such as infection and heart failure.

Determining factors of functional situation at hospital dischargeA greater ability for self care and lower degree of cognitive impairment prior to the fracture were associated independently with better functional recovery at hospital discharge in the multivariate analysis (previous BI β .339 p<.05 95% CI β .21–.46; previous GDS β −3.18 p<.05; 95%CI β −5.06 to −1.29). Delirium on admission lowered the Barthel index by more than 5 points at time of discharge (β 5.48; p=.051; 95%CI β −10.993 to −.023; adjusted R2 .51). Rehabilitation treatment, once its relationship with physical recovery was adjusted to the patient's previous disability, was not a factor that was clearly associated with recovery at time of discharge.

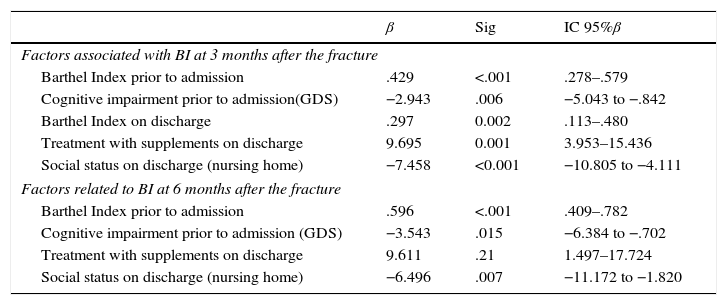

Determining factors of functional recovery at 3 and 6 months after the fractureThree months after the fracture, better physical status prior to admission, the prescription of nutritional supplements and returning home on discharge after adjustment by the remaining associated factors in the univariate analysis (BI and FAC, previous and on discharge, transfusion and rehabilitation on admission, social status) showed an independent relationship with the ability for walking and self care in the multivariate analysis. The patients who returned home scored 7 points more on the BI at 3 months and those who took nutritional supplements almost 10 points more (BI adjusted R2 .70; FAC adjusted R2 .40).

At 6 months after the fracture, the BI and GDS prior to admission, treatment with nutritional supplements and social status at time of discharge maintained their association with functional recovery (BI) in the multivariate analysis, adjusted by the remaining previously related factors (rehabilitation on admission, transfusion, prescription of nutritional factors and living at home and returning home on discharge) (adjusted R2 .57).

The type of fracture was not related to mortality, hospital stay or functional recovery. The patients who received a partial prosthesis had better ability to walk and to self care in the medium term but the difference was not statistically significant.

The list of predictors for better functional outcome (BI) at 3 and at 6 months after the fracture is given in Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with functional outcome – independence for self care (BI) at 3 and 6 months after the fracture.

| β | Sig | IC 95%β | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors associated with BI at 3 months after the fracture | |||

| Barthel Index prior to admission | .429 | <.001 | .278–.579 |

| Cognitive impairment prior to admission(GDS) | −2.943 | .006 | −5.043 to −.842 |

| Barthel Index on discharge | .297 | 0.002 | .113–.480 |

| Treatment with supplements on discharge | 9.695 | 0.001 | 3.953–15.436 |

| Social status on discharge (nursing home) | −7.458 | <0.001 | −10.805 to −4.111 |

| Factors related to BI at 6 months after the fracture | |||

| Barthel Index prior to admission | .596 | <.001 | .409–.782 |

| Cognitive impairment prior to admission (GDS) | −3.543 | .015 | −6.384 to −.702 |

| Treatment with supplements on discharge | 9.611 | .21 | 1.497–17.724 |

| Social status on discharge (nursing home) | −6.496 | .007 | −11.172 to −1.820 |

This was a sample of very advanced age, predominantly female, in line with the references. More than 40% of the patients had some history of heart disease and, therefore, more complications associated with perioperative anaemia and taking more drugs altering haemostasis and involving more risk. With regard to the functional status prior to their fall, this sample had major prior disability, as described in other publications.7

The patients who were in nursing homes before their fracture were more physically impaired prior to their admission and their outcomes were worse. This group had fewer days of hospital say and received less rehabilitation in hospital, possibly because their previous physical status was poorer and because it was possible for them to receive physiotherapy in a different place. The primary care and nursing home coordination teams play an essential role in guaranteeing continuity of care after hospital discharge and in monitoring these patients’ progress, ensuring that their physical recovery is optimal.

The preoperative waiting time of 2 days was lower than that of the majority of publications, and was related to overall stay in this paper, but not with mortality. Due to its demonstrated association with more complications and poorer functional recovery it was a fundamental objective for all the professional practitioners involved.8

The mean stay of 12 days was currently similar to that published in the references for comparable centres, with no attached functional recovery unit, as is the case in our healthcare area.7 If there is no convalescent unit, it is not recommended to reduce the postoperative hospital stay by much more than this, so as to allow a minimum of physical recovery after surgery.9

The most usual medical complications that occur on admission were in line with the literature, delirium and constipation due to perioperative paralytic ileus. Confusional states are clearly associated with poorer physical recovery. Both problems, due to their importance and prevalence, are subsidiary to the protocolised application of specific preventive measures.10 Heart failure and infections were related to mortality and hospital stay, and their prompt and thorough prevention and treatment are a priority.

Five percent mortality is currently comparable to other studies and has progressively improved, as has hospital stay, since the beginning of multidisciplinary intervention.1,11,12

Hip fracture implies acute serious functional impairment. At the time of hospital discharge, 75% of patients were immobile or required the help of 2 people to walk. Severe and acute disability inherent to the process was a cause for admission to a nursing home for almost 40% of those who previously lived at home. Given the short hospital stay, extending rehabilitation treatment in a specific, medium-stay hospital might improve functional recovery and reduce the rate of rehospitalisation. Of the group of patients requiring residential care after hip fracture, 15% will remain there long term. Fractures and their secondary disability mark a turning point for definitive institutionalisation.

Physical recovery after hospital discharge occurs most in the first 3 months after the fracture, the stage at which intervention is most important. However, this can be up to 6 months if there are fewer institutionalised patients. Less than 40% managed to recover the physical ability they had prior to their fall. Care planning for these patients should cover their rehabilitative prognosis in particular, which is related directly to their status prior to the fracture,12–14 and the emphasis should be on treating those who will benefit most, complementing physiotherapy with a specific nutritional approach.

The erythropoiesis stimulation protocol tended to relate to better medium-term functional recovery in this study (3–6m), and this effect was maintained, although to a lesser degree, if a transfusion was required as well. This might be due to the fact that administration of ferrotherapy and EPO enables better aetiological treatment of anaemia, with erythropoiesis stimulation maintained over a longer period of time. The literature clearly supports restricting treatment with transfusion in elective orthopaedic surgery, due to the association of blood products with infections and heart failure in surgical patients.15,16 Papers that assess the effect of intravenous iron vouch for its efficacy in reducing the need for surgical transfusion and thus reducing the risk of complications.17–19 However, in the case of elderly patients with hip fracture, advanced age, comorbidities and the semi-urgent nature of the surgery make it difficult to generalise the recommendation to save blood. The level of haemoglobin at the time of discharge did not influence the ability to self care in the medium term.

Patients who did not require treatment for anaemia to maintain haemoglobin levels above 11g/dl on admission achieved a functional recovery that does not seem to be any poorer than those who received ferrotherapy or transfusion. From this it can be concluded that the universal indication for intravenous iron on admission does not seem correct, and should be based on perioperative haemoglobin levels, although it is true that iron deficiency is a constant component of this process.

The high prevalence of malnutrition and vitamin deficiency in the sample could have influenced not only bone fragility, but also impaired balance and muscle mass that predispose to falls and fractures. According to the mean MNA values, this sample were much more malnourished than the average elderly population of the community.20

The importance of nutritional status on the prognosis of the femoral fracture process make its prompt assessment and treatment a priority.21,22 The high number of patients with malnutrition and a risk of malnutrition are highlighted in this paper (22% and 50%), higher than that described in similar publications (rates of 10% and 40% respectively), although these include younger patients.20 The most poorly nourished patients had more comorbidities, worse physical and mental status prior to admission and a poorer functional outcome after their fracture, unrelated to further complications on admission unlike other studies.21,22

Evaluation of the effect of nutritional supplements alone on the outcome of these patients is difficult due to many confounding factors that affect the functional recovery of such complex patients.23–27 Some meta-analyses in this regard conclude that the results of the papers analysed cannot be generalised and often do not include patients with cognitive impairment.28,29 In our study, treatment with supplements improved functional outcome after the fracture, in an independent and maintained way at 3 and 6 months, after adjustment by the previous baseline status and location at the time of discharge. This relationship was particularly evident in the group of patients at risk of malnutrition. In addition, we consider the simultaneous prescription of dietary recommendations and calcium and vitamin D supplements, and precise physical activities guidelines essential to optimise physical recovery and to reduce the risk of future falls.30

Limitations of the study include the fact that the follow-up could be considered short, limited to the 6 months following the fracture, and that contact with the patients in this period was by telephone, with the disadvantages that this implies. The paper was not able to detect changes in complications or mortality related with the treatment of anaemia.

ConclusionsFunctional status prior to the fracture, measured by the Barthel Index, and the extent of cognitive impairment are reliable parameters associated with short and medium term physical recovery after intervention. They should, therefore, be the basis for planning the individualised treatment of elderly hip fracture patients. Patients who come from home and who can return home after their fracture achieve the best functional recovery medium term, and thus it appears to be a priority objective of intervention to promote sufficient physical improvement for the elderly hip fracture patient to return home as soon as possible.

The administration of alternative treatments to blood transfusion with FE/EPO relates to medium term functional improvement in the frail elderly with a hip fracture, and transfusion is associated with poorer clinical outcomes. Nutritional status is a determining factor in the medium-term physical outcome of hip fracture patients with bone fragility. Nutritional supplements given at the time of discharge promoted functional recovery in patients at risk of malnutrition irrespective of their previous situation.

Functional improvement essentially occurs in the 3 months following hip fracture, rehabilitation efforts should be focussed at this stage.

Level of evidenceLevel II.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the responsible Clinical Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with those of the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have adhered to the protocols of their centre of work on patient data publication.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Pareja Sierra T, Bartolomé Martín I, Rodríguez Solís J, Bárcena Goitiandia L, Torralba González de Suso M, Morales Sanz MD, et al. Factores determinantes de estancia hospitalaria, mortalidad y evolución funcional tras cirugía por fractura de cadera en el anciano. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2017;61:427–435.