Tension band plates (TPBs) are frequently used in guided growth (CG) surgeries. Recently, the concept of removing the metaphyseal screw only to stop the growth modulating effect rather than completely removing the implant, has gained popularity. Although this strategy would have certain potential advantages, the associated risks are unknown. The aim of this study is to report the experience of three institutions with this strategy.

MethodsA database was compiled with the demographic information of patients treated by guided growth using TBPs between January 2014 and January 2019 at three institutions. The cases where only the metaphyseal screw was removed were identified. The records were reviewed to analyze the indications, demographic data, characteristics of the procedure, complications and need for additional procedures.

ResultsWe reviewed 28 partial hardware removals, performed in 10 patients (all male). Initial surgery was indicated for angular deformity (N=6), and leg-length discrepancy (N=4). The average age at the time of surgery was 9.5±2.9 years (range 4–13 years). Three procedures were performed on the distal femur, 3 on the proximal tibia, 2 on the distal tibia, and 20 combined. The average follow-up was 23.3±11 months (range 12–52 months). We observed recurrence of deformities in 7 of 28 (22%) limbs that required re-insertion of the metaphyseal screw. Two patients presented complications from the procedure: soft tissue irritation (N=1) and angular deformity (N=1). Both patients required unplanned surgery.

DiscussionPartial hardware removal in guided growth surgery could favor the presentation of complications. The benefits of this strategy must be considered against the possible undesired effects generated by its application.

Study designTherapeutic study (Level IV).

Las placas en banda de tensión (PBT) son utilizadas con frecuencia en cirugías de crecimiento guiado (CG). Recientemente, ha ganado popularidad el concepto de retirar solo el tornillo metafisario para detener el efecto de modulación del crecimiento, en lugar de retirar completamente el implante. Si bien esta estrategia tendría ciertas ventajas potenciales, se desconocen los riesgos asociados. El objetivo de este trabajo es reportar la experiencia de tres instituciones con esta estrategia.

MétodosSe recopiló una base de datos con la información demográfica de todos los pacientes tratados mediante CG entre Enero de 2014 y Enero de 2019 en tres centros. Se identificaron los casos en los que se realizó solo el retiro del tornillo metafisario. Se revisaron los registros para analizar las indicaciones, datos demográficos, características del procedimiento, complicaciones y necesidad de procedimientos adicionales de estos casos.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 28 retiros parciales, realizados en 10 pacientes (todos masculinos). La cirugía inicial fue indicada en 6 casos por deformidad angular y en 4 casos por discrepancia de longitud. La edad promedio al momento de la cirugía fue de 9.5±2.9 años (rango 4 a 13 años). Tres procedimientos se llevaron a cabo en el fémur distal y 3 en tibia proximal, 2 en tibia distal y 20 en ambos segmentos. El seguimiento promedio fue de 23.3±11 meses (rango 12 a 52 meses). El 25% (7/28 PBT) requirieron re-colocación del tornillo metafisario por recurrencia del diagnóstico inicial. Dos pacientes presentaron complicaciones por el procedimiento: irritación partes blandas (N=1) y deformidad angular (N=1). Ambos pacientes requirieron de una cirugía no programada.

DiscusiónEl retiro aislado del tornillo metafisario en cirugía de crecimiento guiado podría favorecer la presentación de complicaciones. Los beneficios de esta estrategia deben considerarse frente a los posibles efectos no deseados generados por la aplicación de la misma.

Diseño del estudioEstudio terapéutico (Nivel de evidencia IV).

Guided growth surgery (GG) consists in temporarily preventing the growth of long bones in order to correct deformities gradually without permanently damaging the physis. Hueter, Volkmann and Delpech were the first to describe the effect of pressure on epiphyseal growth.1 At the end of 1940, Blount et al.2,3 described an implant which would correct the discrepancy in the length of the extremity and in angular deformities. For over 50 years, the Blount staple (Zimmer, Warsaw, IN, USA) was widely used for the treatment of several pathologies in skeletally immature patients. In 1998, Métaizeau et al. Introduced a technique using transphyseal screws4 which had the advantage of being percutaneous, and this reduced morbidity. However, the disadvantage of damaging the physis with a hard implant has limited its extensive use as a temporary method. Tension band plates (TBP) were introduced a little over a decade ago5 and are the most used system now. This hardware consists of a plate with two openings permitting the insertion of two divergent screws, one epiphyseal and the other metaphyseal, which act by producing an extra-physeal fulcrum, asymmetrically preventing physeal growth. Many study series have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of this hardware when indications are right.6–9

Due to the fact that this technique is reversible, once correction has been obtained, the hardware is removed and this allows for renewed bone growth. Recently, the concept of removing the metaphyseal screw to stop the growth modulation effect has gained in popularity (Sleeping plate).10,11 Those who support this technical modification sustain that maintaining the plate and the epiphyseal screw in situ for future reactivation would minimize morbidity and reduce the cost of further surgery.

The aim of this study was to report the experience of three institutions with this strategy.

MethodsStudy design and populationRetrospective study. Level of evidence 4.

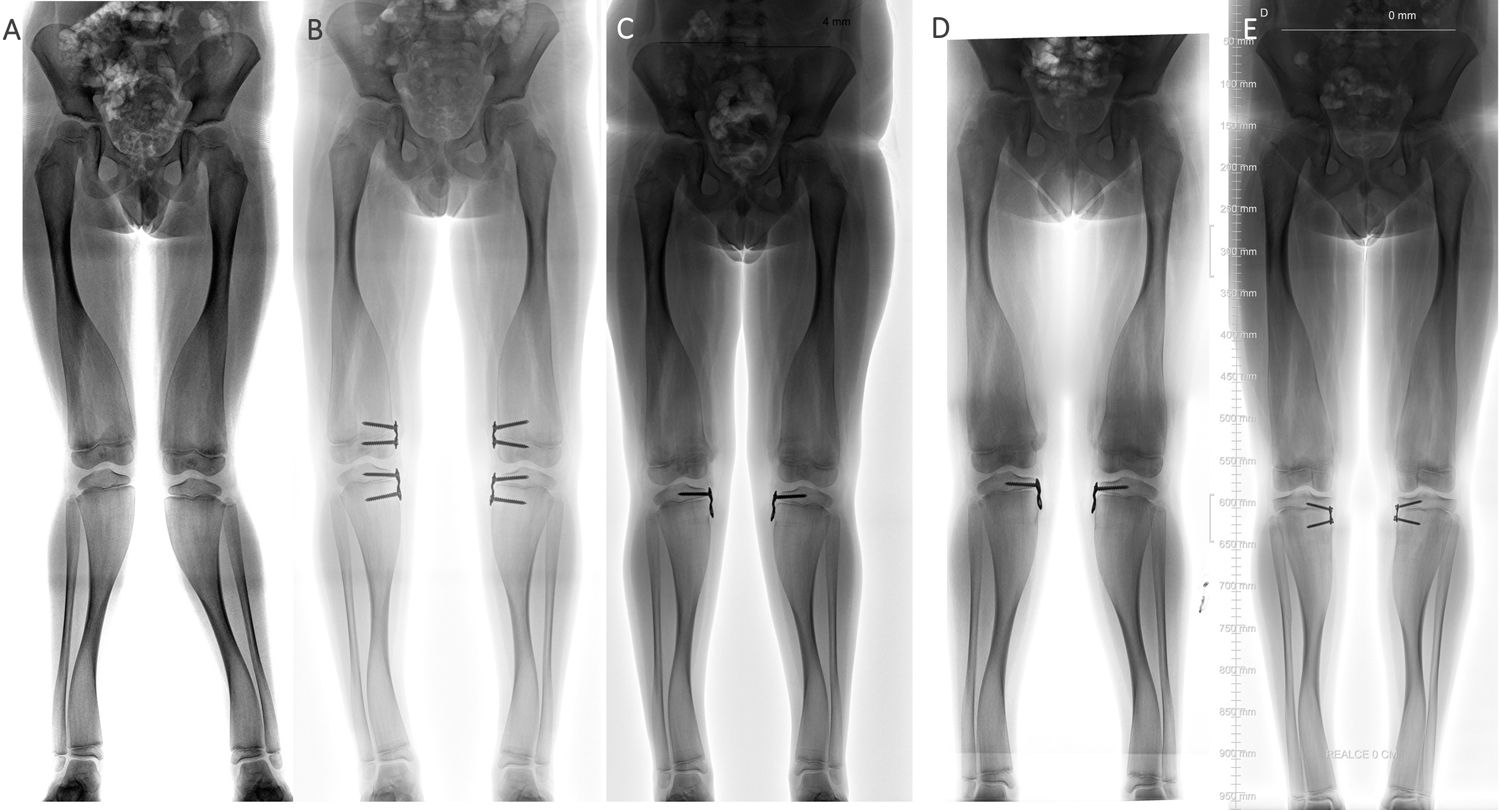

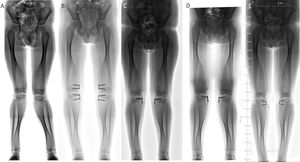

The study was approved by the ethics committee prior to start. The demographic information of all patients treated by guided growth surgery were collected between January 2014 and January 2019. They included for analysis those patients who presented with a minimal follow-up of 12 months from removal of the metaphyseal screw (Fig. 1). The medical records were reviewed to analyse indications, demographic data, prior treatment, procedural characteristics, complications and the need for further procedures. All procedures were performed by five surgeons with formal training in orthopaedic and paediatric surgery. The patients with incomplete records were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysisFor description of the quantitative variables, descriptive statistics were used (average/standard deviation) and for the qualitative variables absolute frequencies.

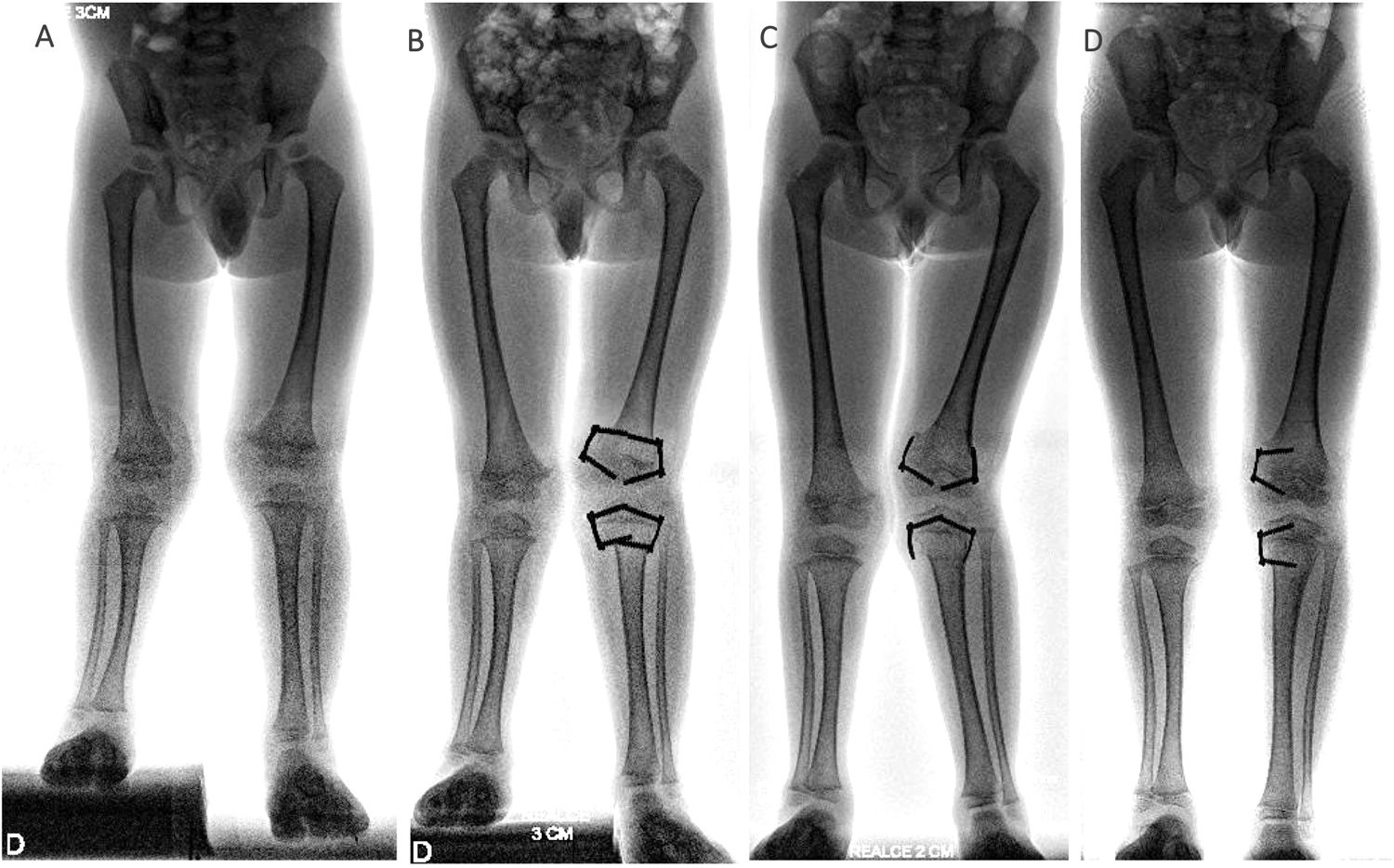

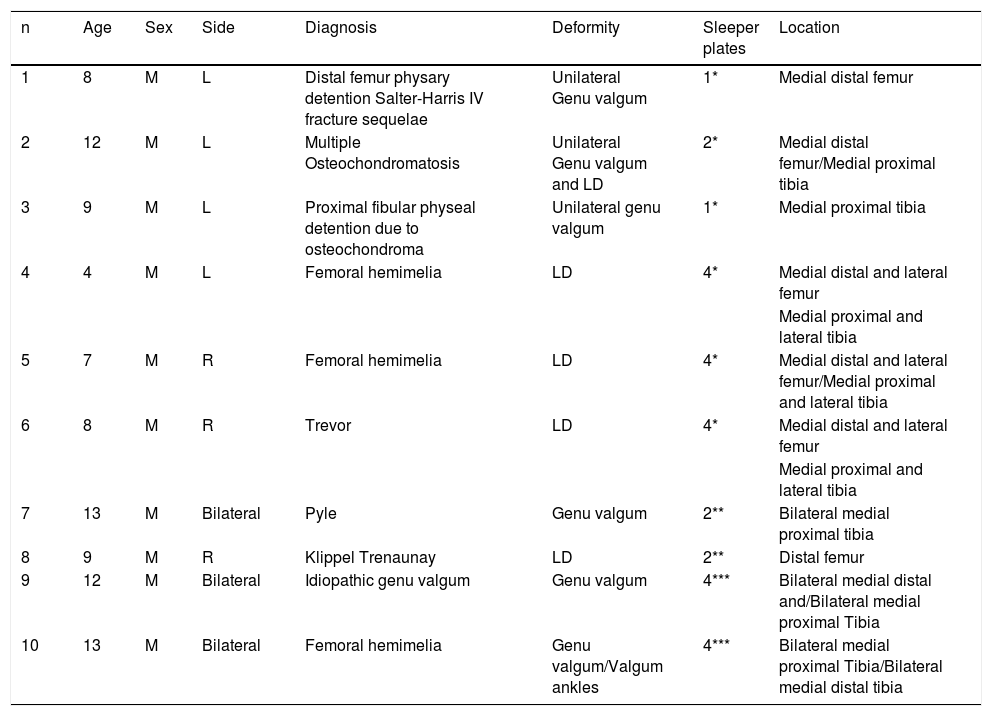

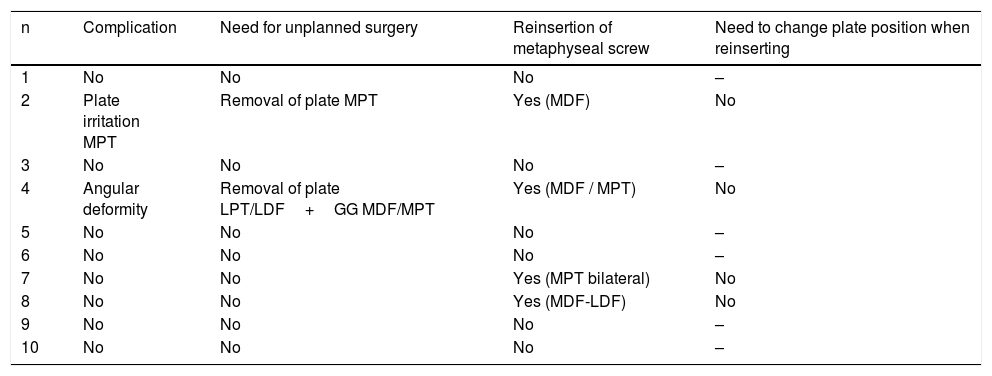

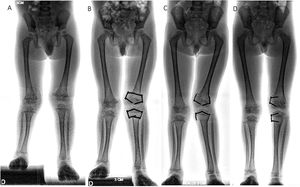

ResultsBetween January 2014 and January 2019, guided growth surgery with TBP was performed on 232 patients in the three centres involved. Of this cohort, 28 partial hardware removal was undertaken in 10 patients (all male). This technique was used on all patients. Initial surgery was indicated in six cases for angular deformity and in four cases for discrepancy of length. The average age at time of surgery was 9.5±2.9 years (range from four to 13 years). Three procedures were undertaken in the distal femur and three in the proximal tibia, two in the distal tibia and 20 in both segments. Average follow-up was 23.3±11 months (range of 12–52 months). Demographic characteristics of the sample are contained in Table 1. Twenty five percent (n=7) of the plates required relocating of the metaphyseal screw due to recurrence of initial diagnosis (Fig. 2). Two plates (7%) presented with complications: soft tissue irritation (n=1) and angular deformity (n=1) (Table 2) (Fig. 3). Both patients required unplanned surgery. There were no implant failures.

Demographic data of patients.

| n | Age | Sex | Side | Diagnosis | Deformity | Sleeper plates | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | M | L | Distal femur physary detention Salter-Harris IV fracture sequelae | Unilateral Genu valgum | 1* | Medial distal femur |

| 2 | 12 | M | L | Multiple Osteochondromatosis | Unilateral Genu valgum and LD | 2* | Medial distal femur/Medial proximal tibia |

| 3 | 9 | M | L | Proximal fibular physeal detention due to osteochondroma | Unilateral genu valgum | 1* | Medial proximal tibia |

| 4 | 4 | M | L | Femoral hemimelia | LD | 4* | Medial distal and lateral femur |

| Medial proximal and lateral tibia | |||||||

| 5 | 7 | M | R | Femoral hemimelia | LD | 4* | Medial distal and lateral femur/Medial proximal and lateral tibia |

| 6 | 8 | M | R | Trevor | LD | 4* | Medial distal and lateral femur |

| Medial proximal and lateral tibia | |||||||

| 7 | 13 | M | Bilateral | Pyle | Genu valgum | 2** | Bilateral medial proximal tibia |

| 8 | 9 | M | R | Klippel Trenaunay | LD | 2** | Distal femur |

| 9 | 12 | M | Bilateral | Idiopathic genu valgum | Genu valgum | 4*** | Bilateral medial distal and/Bilateral medial proximal Tibia |

| 10 | 13 | M | Bilateral | Femoral hemimelia | Genu valgum/Valgum ankles | 4*** | Bilateral medial proximal Tibia/Bilateral medial distal tibia |

M: MaleLD: Length discrepancy.

Characteristics of complications and further surgery.

| n | Complication | Need for unplanned surgery | Reinsertion of metaphyseal screw | Need to change plate position when reinserting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | No | No | – |

| 2 | Plate irritation MPT | Removal of plate MPT | Yes (MDF) | No |

| 3 | No | No | No | – |

| 4 | Angular deformity | Removal of plate LPT/LDF+GG MDF/MPT | Yes (MDF / MPT) | No |

| 5 | No | No | No | – |

| 6 | No | No | No | – |

| 7 | No | No | Yes (MPT bilateral) | No |

| 8 | No | No | Yes (MDF-LDF) | No |

| 9 | No | No | No | – |

| 10 | No | No | No | – |

GG: Guided growth, LDF: Lateral distal femur, LPT: Lateral proximal tibia, MDF: Medial distal femur, MPT: Medial proximal tibia.

Several years ago, certain authors10 recommended using a modified growth guided technique, in which only the metaphyseal screw was removed, leaving the plate and the epiphyseal screw in situ once the desired correction was complete. This meant that if there was a recurrence of deformity, a simpler operation could be performed to reinsert a single screw instead of carrying out the whole surgical procedure. The advantages would be related to a lower surgical dissection, lower morbidity and costs (one screw vs. one plate+two screws). In our series we observed that most patients where the hardware had been partially removed did not require reinsertion of the metaphyseal screw because there was no recurrence of deformity. Only seven of the 28 plates were reused, and their usefulness was therefore lower than expected. Only two studies describe a cohort of patients treated with this modification.7,8 Kadhim et al.11 assessed 13 physes where this strategy was used, but only three (23%) had recurrence and the metaphyseal screw had to be replaced. Keshet et al.12 assessed 55 segments, of which only 12 (22%) required a new guided growth procedure. Unfortunately, only in three of these cases were the plate and the epiphyseal screw found to be in an appropriate position for re-insertion of the metaphyseal screw. In the other nine cases, the authors had to change the plate and both screws. This problem did not arise in any of the cases in our series.

Although leaving part of the hardware in situ would have certain potential advantages, the associated risks to this practice are unknown. In one of the cases in our series, we observed a prolongation of the tension band effect, which led to undesirable secondary deformity and this could have been connected to the formation of scar tissue between the plate and the metaphysis or a bony bridge. According to Keshet et al.12 the anchorage of the plate to the physis long term would be a risk associated with physary detention. In their series, two patients developed a physary rod which required surgical correction. Kadhim et al.11 proposed the separation of the metaphyseal plate when it had been partially removed and placing wax in-between the two. Although this surgical procedure would reduce the chances of metaphyseal plate anchorage, it would increase risk of irritation by greater prominence of the plate in the soft tissues.

The results of our study should be interpreted within the context of the limitations presented by its retrospective design. Despite being a multicentre study, the sample is small, which may magnify or underestimate the incidence of associated complications to the practice of partial hardware removal in guided growth. It should be taken into consideration that this strategy was applied only in specific cases, where it was considered that it would benefit the patient. Despite these limitations, we believe that this study contributes the experience of three centres from the last five years and how it has resulted in us modifying our practice. Following analysis of this sample, two of the three centres involved decided to discontinue application of this strategy. The remaining centre considers that it may be applied in highly select cases which present with a high probability of recurrence, provided that the plate is inserted in an ideal position.

To conclude, the isolated removal of the metaphyseal screw in guided growth surgery could lead to the presentation of complications, which requires further study. The benefits of this strategy should be considered compared to the possible undesired effects generated by their application.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Masquijo J, Allende V, Artigas C, Hernández Bueno JC, Morovic M, Sepúlveda M. Retiro parcial del implante en cirugía de crecimiento guiado: ¿una estrategia conveniente? Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2021;65:195–200.