To describe the characteristics of patients with periprosthetic femoral fractures after hemiarthroplasty and to analyse their treatment.

Materials and methodsAn observational, longitudinal, retrospective study was conducted on a series of 17 patients with periprosthetic femoral fractures after hip hemiarthroplasty. Fourteen fractures were treated surgically. The characteristics of patients, fractures and treatment outcomes in terms of complications, mortality and functionality were analysed.

ResultsThe large majority (82%) of patients were women; the mean age was 86 years with an ASA index of 3 or 4 in 15 patients. Ten fractures were type B. There were 8 general complications, one deep infection, one mobilisation of a non-exchanged hemiarthroplasty, and 2 non-unions. There were 85% consolidated fractures, and only 5 patients recovered the same function prior to the injury. At the time of the study 9 patients had died (53%).

DiscussionPeriprosthetic femoral fractures after hemiarthroplasty will increase in the coming years and their treatment is difficult.

ConclusionPeriprosthetic femoral fractures after hemiarthroplasty are more common in women around 90-years-old, and usually occur in patients with significant morbidity. Although the Vancouver classification is reliable, simple and reproducible, it is only a guide to decide on the best treatment in a patient often fragile. The preoperative planning is essential when deciding a surgical treatment.

Describir las características de los pacientes y las fracturas femorales periprotésicas sobre hemiartroplastias, y realizar un análisis del tratamiento a partir de sus resultados.

Material y métodoEstudio observacional, longitudinal y retrospectivo de una serie de 17 pacientes con fracturas femorales periprotésicas sobre hemiartroplastias de cadera. Catorce se trataron quirúrgicamente. Se analizaron las características de los pacientes y de las fracturas y los resultados del tratamiento en términos de complicaciones, mortalidad y funcionalidad.

ResultadosEl 82% de los pacientes fueron mujeres, la edad media fue de 86 años y el índice ASA de 15 de ellos fue 3 o 4. Diez fracturas fueron de tipo B. Se registraron 8 complicaciones generales, una infección profunda, una movilización de la hemiartroplastia no recambiada y 2 seudoartrosis. Consolidaron el 85% de las fracturas y solo 5 pacientes recuperaron la función previa al traumatismo. Al final del estudio habían fallecido 9 pacientes (53%).

DiscusiónEl tratamiento de las fracturas periprotésicas sobre hemiartroplastias, cuya frecuencia aumentará en los próximos años, es difícil.

ConclusionesLas fracturas femorales periprotésicas sobre hemiartroplastias son más frecuentes en mujeres próximas a los 90 años y suelen ocurrir en pacientes con importante morbilidad. La indicación de su tratamiento no debe basarse solo en la clasificación de Vancouver que, aunque fiable, simple y reproducible, no deja de ser una guía para decidir el mejor tratamiento en un paciente a menudo frágil. Cuando aquel sea quirúrgico, la planificación preoperatoria es fundamental.

Fractures of the femur with some previously implanted material are relatively frequent. Among them, periprosthetic fractures in patients with hip or knee prostheses constitute the majority, and their incidence is increasing day by day because more and more arthroplasties are being implanted due to the ageing and greater demands of the population. The increase of osteoporotic hip fractures for the same motive is another reason. Treatment for all of these fractures is difficult and represents a challenge for multidisciplinary orthogeriatric teams, which have to take care of fracture demands in a context that is often of local and general fragility.

The overall incidence of periprosthetic femoral fractures in patients with total hip prostheses is estimated to be around 1–6%, with figures of 1% among the primary and of 2–6% among those of revision (always greater if they are not cemented).1–5 There are numerous publications about this and the majority of them refer to patients with total prostheses, when they do not group patients with total prostheses and hemiarthroplasties together, or postoperative with intraoperative fractures. Postoperative periprosthetic femoral fractures after hemiarthroplasties have seldom been studied specifically. In fact, in the revisions on the matter carried out by Marsland and Lears,5 Giannoudis et al.3 and Schwarzkopf et al.4 (adding up to a total of 246 references), there is only 1 that expressly mentions periprosthetic fractures after hemiarthroplasties in its title. In addition, the article in question dates back to 1986.6

Hemiarthroplasties or partial hip prostheses are indicated in displaced fractures of the femoral neck or as a rescue for failed osteosynthesis in fractures of this type. The usefulness of the head bipolarity7 and the age of the patient that is to receive the implant are controversial, given that total prostheses offer better results than partial ones. Cemented prostheses, on the other hand, are preferable to non-cemented ones because they also achieve better functional results.8 In our service (although not as a strict rule and always taking into account general patient condition and any comorbidity), we routinely indicate hemiarthroplasty, always cemented, in patients older than the mean expected survival age in our region, reserving the unipolar Thompson model for the patients of greater age with worse general or functional condition. Life expectancy for the population in Castilla-León is currently calculated to be 81 years for males and 83 years for women.

Based on everything that has been indicated previously and considering the demographic characteristics of the population in our setting, which allows us to work with a sample that we estimate as sufficient and relatively homogeneous, we carried out this study, with the following objectives: (1) describe the patient characteristics and the periprosthetic femoral fractures after hemiarthroplasties and (2) critically analyse the treatments given based on their results.

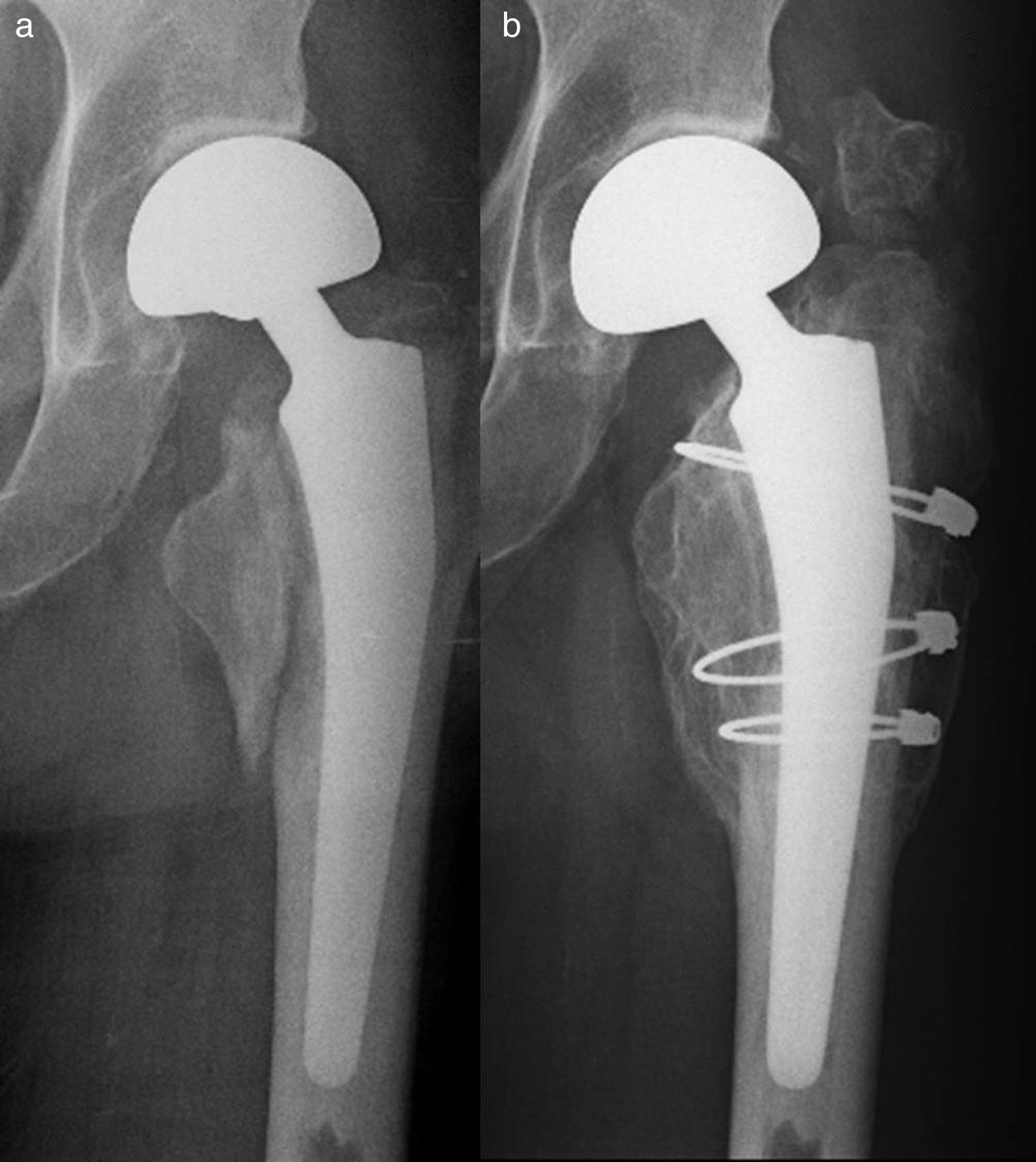

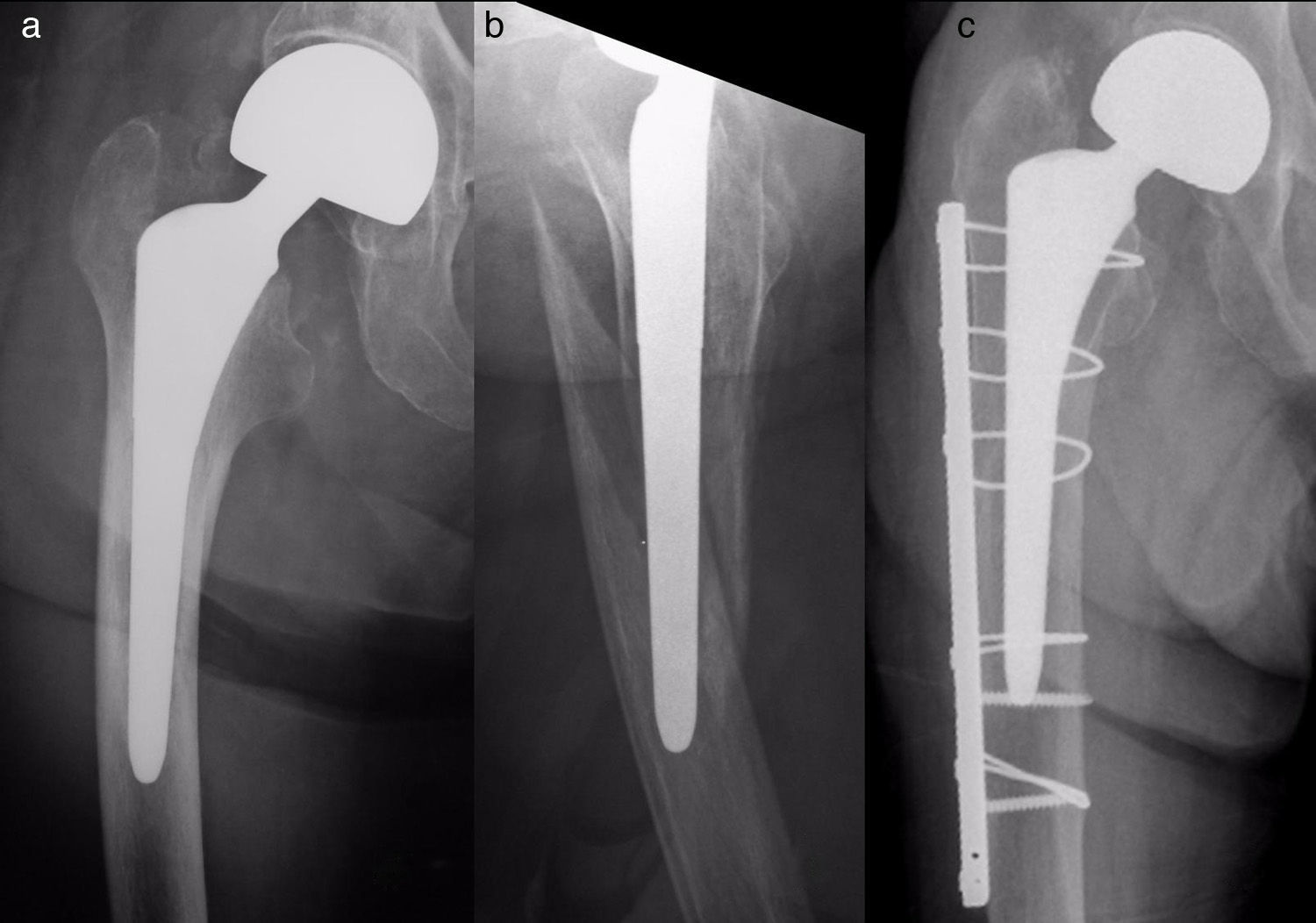

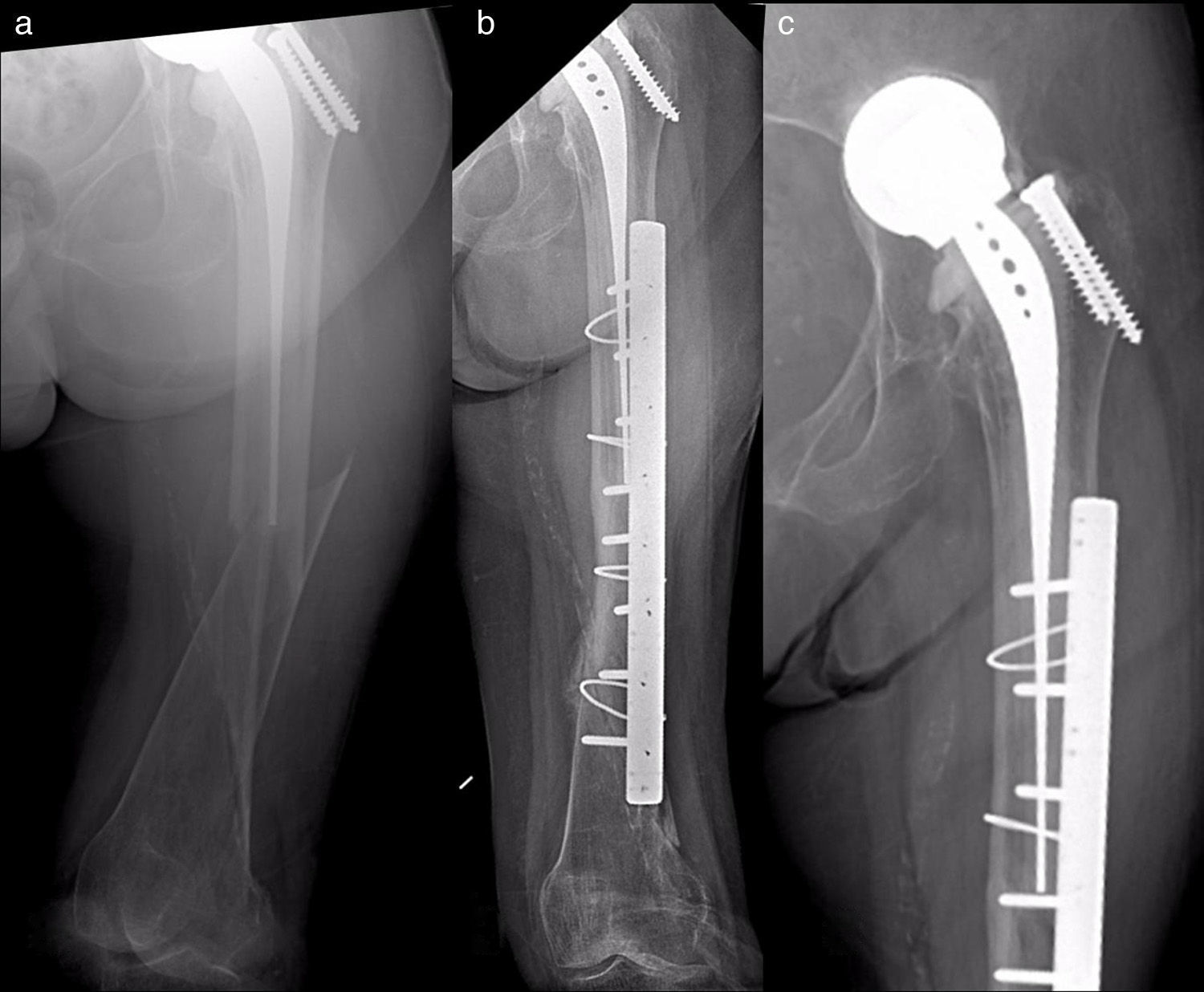

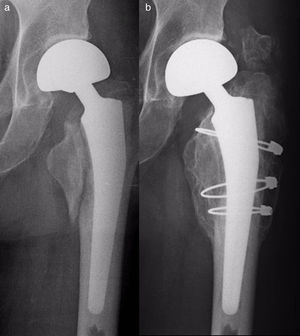

Materials and methodsThis was a retrospective, observational, longitudinal study on a series of 17 patients with periprosthetic femoral fractures after hip hemiarthroplasties seen on a continuous basis in our service from 2005 to 2013 (1 in 2005, 1 in 2007, 2 in 2008, 2 in 2009, 6 in 2011, 2 in 2012 and 3 in 2013). Seven hemiarthroplasties were unipolar (6 Thompson type and 1 isoelastic Mathys type), while 10 were various bipolar models. All the unipolar were cemented, including the isoelastic, which was implanted and cemented in another centre. Among the bipolar models, 6 were cemented and 4, cementless. Two fractures were AL type according to the Vancouver classification5,9 (Fig. 1); 10 were type B (6 B1 – Figs. 2 and 3 and 4 B2 – Fig. 4); and 5 were type C (Fig. 5). Three fractures were treated orthopaedically due to fracture type (Case 9) or to the combination of poor general patient condition and poor function (Cases 10 and 12). The remaining patients (14) were treated surgically. Table 1 details the treatment for each case. Cases 4 and 7 were treated with retrograde intramedullary supracondylar nailing (SCN) type (Stryker) nails, which were not overlaid with the prosthesis stem in any case.

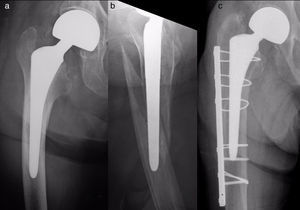

Case 15. (a) Type B1 fracture; (b) postoperative radiographic monitoring 3 months after the intervention, with delay in consolidation and varus shift in the fracture; (c) radiographic monitoring 3 months after having changed the first plate, which still remains short, with precarious proximal fixation and which has varus shift again.

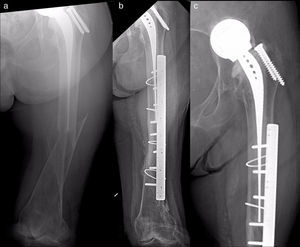

Case 11. (a) Type C fracture after isoelastic hemiarthroplasty; (b) postoperative radiographic monitoring 6 months afterwards, with fracture consolidation; (c) detailed view of the prosthesis, with signs of cotyloid infection. All the images show that the stem had been cemented when it was implanted, more than 20 years before the fracture.

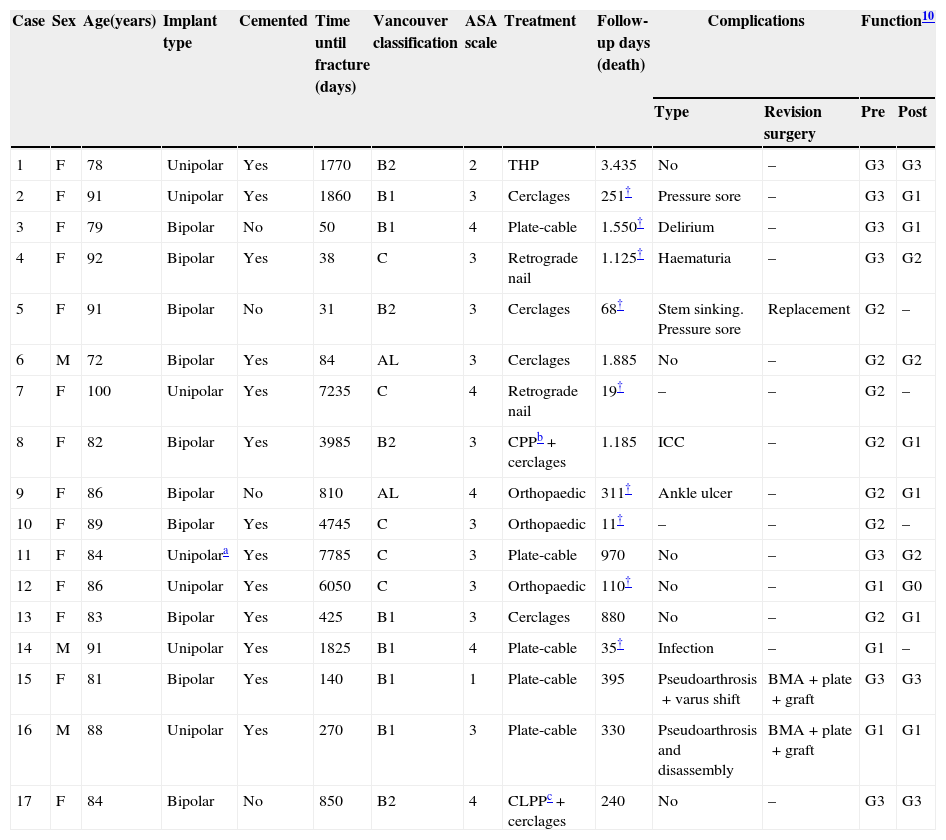

Summary of the cases in the series, their treatment and results.

| Case | Sex | Age(years) | Implant type | Cemented | Time until fracture (days) | Vancouver classification | ASA scale | Treatment | Follow-up days (death) | Complications | Function10 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Revision surgery | Pre | Post | ||||||||||

| 1 | F | 78 | Unipolar | Yes | 1770 | B2 | 2 | THP | 3.435 | No | – | G3 | G3 |

| 2 | F | 91 | Unipolar | Yes | 1860 | B1 | 3 | Cerclages | 251† | Pressure sore | – | G3 | G1 |

| 3 | F | 79 | Bipolar | No | 50 | B1 | 4 | Plate-cable | 1.550† | Delirium | – | G3 | G1 |

| 4 | F | 92 | Bipolar | Yes | 38 | C | 3 | Retrograde nail | 1.125† | Haematuria | – | G3 | G2 |

| 5 | F | 91 | Bipolar | No | 31 | B2 | 3 | Cerclages | 68† | Stem sinking. Pressure sore | Replacement | G2 | – |

| 6 | M | 72 | Bipolar | Yes | 84 | AL | 3 | Cerclages | 1.885 | No | – | G2 | G2 |

| 7 | F | 100 | Unipolar | Yes | 7235 | C | 4 | Retrograde nail | 19† | – | – | G2 | – |

| 8 | F | 82 | Bipolar | Yes | 3985 | B2 | 3 | CPPb+cerclages | 1.185 | ICC | – | G2 | G1 |

| 9 | F | 86 | Bipolar | No | 810 | AL | 4 | Orthopaedic | 311† | Ankle ulcer | – | G2 | G1 |

| 10 | F | 89 | Bipolar | Yes | 4745 | C | 3 | Orthopaedic | 11† | – | – | G2 | – |

| 11 | F | 84 | Unipolara | Yes | 7785 | C | 3 | Plate-cable | 970 | No | – | G3 | G2 |

| 12 | F | 86 | Unipolar | Yes | 6050 | C | 3 | Orthopaedic | 110† | No | – | G1 | G0 |

| 13 | F | 83 | Bipolar | Yes | 425 | B1 | 3 | Cerclages | 880 | No | – | G2 | G1 |

| 14 | M | 91 | Unipolar | Yes | 1825 | B1 | 4 | Plate-cable | 35† | Infection | – | G1 | – |

| 15 | F | 81 | Bipolar | Yes | 140 | B1 | 1 | Plate-cable | 395 | Pseudoarthrosis+varus shift | BMA+plate+graft | G3 | G3 |

| 16 | M | 88 | Unipolar | Yes | 270 | B1 | 3 | Plate-cable | 330 | Pseudoarthrosis and disassembly | BMA+plate+graft | G1 | G1 |

| 17 | F | 84 | Bipolar | No | 850 | B2 | 4 | CLPPc+cerclages | 240 | No | – | G3 | G3 |

death; BMA: bone marrow aplasia; CLPP: cementless partial prosthesis; CPP: cemented partial prosthesis; F: female; M: male; THP: total hip prosthesis.

The unipolar prosthesis used in Case 11 was the Mathys isoelastic model. The rest of the unipolar prostheses were the Thompson model.

Analysis was carried out on the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the patients in the series, the circumstances in which the fractures occurred and the treatment results with a mean follow-up of 2 years and 23 days until the end of the study or patient death, when applicable (range: 11 days–9 years and 5 months). Results included the local and general complications, readmissions and reinterventions, percentages of consolidation and need for transfusion, mortality data, functional results (G3=walks without support or with a cane; G2=walks with 2 supports or with a walker; G1=requires wheelchair to move around; G0=does not walk or is a bed patient),10 length of hospital stay and destination after discharge. Pseudoarthrosis cases and reinterventions were defined as surgical treatment failures. No patient was lost during follow-up.

Surgical treatment, when applicable, was carried out on all patients by physicians in the Hip Unit of the Service according to prevailing surgical protocols. Orthopaedic treatment in the patients that received it consisted of member unloading (Case 9) or immobilisation with inguinal-pedicle plaster (Cases 10 and 12). Patients were discharged when their general condition permitted; patients were sent to a subsidised centre in the same location when they required chronic care not available in another destination. All patients received follow-up in external consultation 1 month after hospital discharge and, after that, at the third and sixth months. Further follow-up visits were annual until patient death.

The information for the study was gathered by the first 2 study authors based on patient medical history review, completing the data in all cases by a telephone interview with each patient (or with the patient's relatives or caregivers if the patient had died or was not in condition to respond to the interview). All data treatment was anonymous and confidential, with the data being transferred to a database created with Microsoft Excel 2000 programme, with which the statistical analysis was performed. This consisted of a descriptive analysis of the variables, calculating the distribution of frequencies for the qualitative variables and the median and interquartile range (IQR) for the quantitative. Approval from the hospital's Ethics Committee was unneeded.

ResultsEpidemiological and clinical resultsOf the 17 patients in the series, 14 (82%) were women and 3 (18%) were men. Median age was 86 years and the IQR ranged from 72 to 100 years. For the men only, these statistics were a median age of 84 years and the IQR, from 72 to 91; for the women, they were 86 years and IQR, from 78 to 100. Nine fractures involved the right side and 8, the left side. Six patients had some degree of dementia; 6 were on hemostasis-modifying drugs (1 took Adiro 100® and 5, Sintrom®), with a mean intake of 4.7 drugs (range: 0–9). The mean value of the Barthel index was 57 (range: 20–95), and that of the appraisal of self-care agency (ASA) scale, 3.1. The ASA value and functional condition for each patient are indicated in Table 1.

Fifteen fractures occurred in the patient's normal residence, while 1 was produced during hospital admission (Case 10) and another in the street (Case 11). Fracture cause was an accidental fall in 16 patients. In 1, the fracture was produced by a movement in bed (Case 16). In that patient the fracture occurred 9 months after implanting the hemiarthroplasty, which was complicated by an intraoperative fracture that required fixation with 3 cerclages in the same operation, which could have promoted the new fracture. The periprosthetic fractures arose after a mean time of 6 years and 1 month from the hemiarthroplasty implant (range: 31 days–21 years and 4 months). The fracture occurred in the first 3 months that followed after the original implant in 4 patients (Cases 3, 4, 5 and 6).

Results of the treatmentGeneral complications in the series included 2 cases of pressure sores, 1 ankle ulcer, 1 delirium, 1 haematuria, 1 congestive heart failure and 2 progressive multisystem failures that led to the death of both patients at 11 days and 19 days of the intervention (Cases 10 and 7). Case 10 was diagnosed with multiple myeloma.

Local complications related to the surgical intervention included 1 infection (from Proteus mirabilis) in a patient that died 35 days after the intervention from multisystem failure (Case 14), 1 postoperative mobilisation of the original prosthesis (Case 5) and 2 cases of pseudoarthrosis (Cases 15 and 16). These last 2 were type B1 fractures treated with Ready type cable-plate systems that seemed short to us in postoperative radiographic monitoring and with a precarious proximal fixation (Fig. 3). Both patients were readmitted and operated again with the replacement of the same fixation system and provision of homograft. At present, 4 and 8 months after the revision surgery, they are still alive and have function similar to that before the periprosthetic fracture. The prosthetic mobilisation occurred in a 91-year-old woman that had a type B2 fracture, initially misinterpreted as a B1 and treated with 3 cerclages. Due to immediate sinking of the original prosthesis, she was reoperated and the prosthesis was changed; however, the patient died 68 days after the first surgery during her hospital stay. Excluding 4 patients in whom there was insufficient time for consolidation because of their early death (Cases 5, 7, 10 and 14), 11 fractures were consolidated from the remaining 13 (including Cases 9 and 12 treated orthopaedically) (85%). In all, 3 patients of the 14 operated on were surgical failures (21%). Of the total cases operated, 10 required intra- (2 cases) or postoperative (9 cases) blood transfusions.

Nine patients had died at the end of the study, after a mean time period of 387 days since the treatment (range: 11–1550 days). Seven died during the first year, 4 during the first trimester and 2 during the first month. Three patients died during their hospital stay (Cases 5, 7 and 10). Mean age of all the deceased was 89 years; 8 were women, 5 suffered from some degree of dementia, an average of 5.4 drugs were taken, mean Barthel index was 41 and mean ASA score was 3.4 (4 patients with ASA 4).

The functional results of the treatment are detailed in Table 1. Only 5 patients recovered their level of pre-trauma function (Cases 1, 6, 15, 16 and 17).

Although 3 patients were transferred to subsidised centres following hospital discharge (Cases 11, 14 and 15), the mean stay in our hospital was 16 days, with an IQR of 1 day (Case 12) to 72 days (Case 5). Excluding the extreme cases 12 and 5, mean hospital stay was 13.5 days. Mean hospital stay for the cases operated was 18 days.

DiscussionHemiarthroplasty is the treatment of choice for displaced fractures of the femoral neck in patients of advanced age.7,11–13 Femoral fractures after hemiarthroplasties are relatively rare and the subject has received much less attention that this type of fracture in femurs with total arthroplasties.13–16 The exception to this statement is the series of Phillips et al.17 including 79 patients with periprosthetic fractures after hemiarthroplasties recruited consecutively from 1999 to 2010.

Periprosthetic femoral fractures in patients with hemiarthroplasties complicate 0–14% of these interventions and are more frequent in cementless implants,11–15,17–19 which is the reason why these are usually discouraged at the present time. The incidence in cemented stems is estimated to be 0–2% of the cases, while in cementless stems, the estimate is 4–14%. Insofar as age and sex, the age is generally around 85 years and the patient is usually female, as in our experience.13,17 The condition has been described more frequently in femurs with bipolar implants than in unipolar in a few series, although it has been impossible to specify if this finding was incidental or related with some unknown factor.14 In all cases, including fractures on total prostheses, the most frequent are those of type B (Vancouver classification), representing 30–80% of the total.4,17,20 In the series of McGraw et al.,13 who analysed 15 patients with fractures on Austin-Moore type cementless prostheses, 13 (87%) were of type B2. In contrast with our series, those researchers did not find any type C fractures.

Mean time between total prosthesis implant and fracture is calculated to be 7.4–8.1 years, and 3.9 years when it is a revision prosthesis.4,5 With a hemiarthroplasty the mean time lapse in the series published has been 24–35 months,13,17 although those diagnosed during the first month were possibly unnoticed intraoperative fractures.17 In our series, the fact that the fractures occurred at the end of a mean time of more than 6 years might be because the majority were after cemented hemiarthroplasties, which provide the femur more resistance in a hypothetical fall.

While the most frequent causes of a postoperative fracture of a femur with a total hip prosthesis are aseptic loosening of the arthroplasty and falls,4 the fractures produced after hemiarthroplasties generally develop without prosthetic loosening. Apart from the technical factors that make the bone more fragile during the primary operation (as in our previously-mentioned Case 16), predisposing factors are considered to be female sex, rheumatoid arthritis, massive osteolysis, advanced age and the osteoporotic disease itself.5 At any rate, the majority are the result of low-energy falls from a seated or standing position.

Treating a periprosthetic femoral fracture in a patient with a hemiarthroplasty is difficult and expensive,15 and requires precise therapeutic planning with respect to indication and method. You have to consider the general condition of the patient (often fragile), rule out any underlying infection3,5 and determine exact fracture type and implant stability, as well as bearing in mind the surgeon's experience.16 To mobilise the patient rapidly and have them recover function, it is necessary to achieve and maintain fracture reduction, ensure implant stability and accelerate osseous healing.

As for the type of fracture, type A fractures are usually treated with conservative measures. However, they could compromise implant stability with large fragments or significant periprosthetic osteolysis. Type B1 fractures are normally treated with open reduction and internal fixation using plates or cerclages. Types B2 and B3 are generally treated by replacing the prosthesis with another,13 cemented or not, combined with internal fixation or not. Finally, type C fractures are usually treated with hybrid plates with proximal unicortical screws and cables and distal bicortical; intramedullary devices are reserved for cases in which lesser surgical aggression is desired, attempting to overlay the stem and the nail to avoid stress zones between them.3,4,21 In reference to this, Zuurmond et al.22 demonstrated that this system, with a specially-designed nail, achieved stable connection with the femoral stem and provided sufficient strength to resist full load. The stem length to be overlaid would be 2–3.5cm. This was not, in either of the 2 cases in our series, even attempted. Another possibility, in selected cases, above all in young patients, would be to combine intramedullary fixation with extramedullary.23 In all Vancouver classification fractures, structural cortical homografts could be used as additional stabilising elements.

In our series, 1 of the 2 type AL fractures was operated because it was thought that fracture displacement could compromise implant stability through loss of its medial support. The other AL case was treated orthopaedically, as were 2 other patients for whom surgery was inadvisable after anaesthetic evaluation because of high surgical risk and poor previous functional condition. The remaining patients received surgical interventions appropriate to their type of fracture. Cerclages, plates-cable with uni- and bicortical screws were used as osteosynthesis methods; in 2 patients, retrograde nails that provided discrete but sufficient fixation were also used, taking the estimated survival into consideration. We never used block plates or minimally invasive techniques to implant them, which are described as methods especially useful in osteoporotic bones.4,5,16 Neither were clamping plates joined to others to allow lateralised fixation of bicortical screws used.20

Patient condition, as well as functionality, consequently affects the therapeutic decision in that a procedure of greater morbidity can be rejected for another that might yield lower morbidity.4,16 The fact that the age of patients with periprosthetic fractures after hemiarthroplasties is so advanced works in favour of this measure, as does its frequent associated comorbidity.17 In our series, 15 of the 17 patients had elevated anaesthesia risk of ASA 3 or 4.

There are many complications after surgical treatment of periprosthetic fractures. A 7–23% of revision surgeries are foreseen in series with a predominance of total arthroplasties.2,5,24,25 Pseudoarthrosis can be seen in up to 57% of the cases and is difficult to treat.26 Deep infections are also difficult, with the possibility of suppressive treatment in patients of advanced age.5 In hemiarthroplasty series, complications are expected to occur in 42% of the patients, with 3–25% infections, 1–8% haemorrhages and 1–8% assembly failures.13 In the series of Phillips et al.,17 there were 55% medical complications, 4.5% deep infections, 3% pseudoarthrosis cases, 1 luxation and 11% revision operations. The 3 failures in our series represented 21% of the cases operated. Two type B1 fractures were complicated with pseudoarthrosis, attributed to the fact that the plate had been excessively short and had an equally precarious proximal fixation. Although the screw can compromise the cement layer and it is necessary to attempt to reduce their number near the focus of the fracture, at the proximal level at least 4 cortical screws must grip. When the fracture is fixed with a plate, its length should exceed the fracture by, at least, 2 femur widths, which did not happen in our 2 patients. Our third complication was due to classifying a B2 fracture as a B1 and not replacing the original prosthesis in the first surgery, as is recommended.2–5,27,28 Although the implant was shown to be unstable intraoperatively, the decision was made not to replace it in benefit of a shorter intervention with lower morbility. Later evolution of the case showed that this had not been a good choice, although it probably would not have changed even if the prosthesis had been replaced. At any rate, optimum plate length is unknown, biomechanical studies on the most stable assemblies have not been clinically validated, the general patient condition justifies orthopaedic treatment in some B2 fractures6 and our failure index is compatible with those of other series, which estimate a 24–34% failure rate in treating type B1 fractures.5,20

Insofar as mortality of patients with periprosthetic fractures, at 6 months this is calculated to be about 7% in total arthroplasties, and between 9% and 11% at 1 year, although it is higher among males and with increasing age.4,5 However, in the case of hemiarthroplasties, the figures are significantly higher. In the Phillips et al. series,17 11% died during the first postoperative month, 23% in the first 3 months, 34% by 1 year, 49% at 2 years and 63% at 3 years. In our series, with a mean follow-up of more than 2 years, the figures for the first month, first trimester and at 1 year were 12%, 24% and 41%, respectively. At the end of the study, 53% of the patients had died, with a worse Barthel index score and anaesthesia risk, as was to be expected, than in the global in the series.

Postoperative functional recovery among the survivors is unpredictable. In the McGraw et al. series,13 75% of patients had a significant reduction of mobility. Functional results are equally poor in more than half of the patients with B2 fractures treated with isolated internal fixation.3 In our series, only 29% recovered their functional level from before the trauma.

Our study had various limitations, which are repeated in the majority of articles on this subject. The first is that it is a retrospective study. The second is the limited number of cases involved. The third was that there were no control groups for comparison. In spite of this, we consider that the sample was relatively uniform and sufficient. We can also emphasise the study strength represented by the facts that our Service was the only one that treated these fractures in our health care area and that specialists having similar training and commitment managed all the cases.

In conclusion, periprosthetic femoral fractures after hemiarthroplasties are likely to increase in frequency in the coming years and have to be taken into consideration. In our setting, such fractures are more frequent in women of an age of approximately 90 years and usually occur in patients with important morbidity. The indication for their treatment should not be based solely on the Vancouver classification, which (although reliable, simple and reproducible) can only be considered a guideline for deciding on the best treatment for a frequently fragile patient. When such treatment is surgical, preoperative planning is fundamental.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Therapeutic study level IV (case series).

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or animals were performed in this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that their work centre protocols on publication of patient data were followed in this study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained the informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in this article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FundingThe authors have not received any funding for preparing this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Suárez-Huerta M, Roces-Fernández A, Mencía-Barrio R, Alonso-Barrio JA, Ramos-Pascua LR. Fracturas periprotésicas de fémur sobre hemiartroplastia. Análisis de una serie de 17 casos. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2015;59:333–342.