To evaluate the clinical results and survival of primary hip prosthesis with ceramic delta bearings (C-C) with a minimum follow-up of 5 years.

Material and methodA total of 205 primary hip arthroplasties performed between 2008 and 2012 were studied. The clinical results, pre-surgical and at 5 years of follow-up were evaluated using the Harris Hip Score (HHS), the Short Form-36 (SF-36), the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), and the visual analogue scale (VAS). The position of the prosthetic components, periprosthetic osteolysis, loosening of the prosthetic components and ruptures of the ceramic components were studied radiologically. The adverse events related to bearings were recorded according to their diameter, paying special attention to prosthetic dislocations and the presence of noise. Survival with an endpoint of prosthetic revision for any cause was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

ResultsSignificant improvements were obtained in the HHS (88.7% of good/excellent results), SF36, WOMAC and EVA, p<.001. There were 19 adverse events related to the prosthesis (4 periprosthetic fractures, 4 dislocations, 2 superficial infections, 1 mobilisation of the cup, 2 noises, 4 aseptic loosenings and 2 breaks of the prosthetic neck); 47.3% needed revision. The cumulative survival of the prostheses was 97.5% (95% CI: 96.4–98.5). No differences were found in survival, prosthetic adverse events, noise incidence or dislocations and clinical results among the different diameters used.

ConclusionsPrimary hip prostheses with fourth-generation ceramic bearings showed good survival in the medium term, and good clinical results.

Evaluar los resultados clínicos y la supervivencia de las prótesis de cadera primarias con par cerámica-cerámica (C-C) de cuarta generación implantadas en nuestro centro con un seguimiento mínimo de 5años.

Material y métodoSe estudiaron 205 artroplastias primarias de cadera realizadas entre 2008 y 2012. Los resultados clínicos, prequirúrgicos y a los 5años de seguimiento fueron evaluados mediante el Harris Hip Score (HHS), el Short Form-36 (SF-36), el Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) y la escala analógica visual (EVA). Radiológicamente se estudiaron la posición de los componentes protésicos, la osteólisis periprotésica, el aflojamiento de los componentes protésicos y las roturas de los componentes cerámicos. Se registraron los eventos adversos relacionados con el par según su diámetro, con especial atención a las luxaciones protésicas y a la presencia de ruidos. La supervivencia con punto final como revisión protésica por cualquier causa fue estimada mediante el método de Kaplan–Meier.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron mejorías significativas del HHS (88,7% de resultados buenos o excelentes), SF-36, WOMAC y EVA, p<0,001. Se presentaron 19 eventos adversos relacionados con la prótesis (4 fracturas periprotésicas, 4 luxaciones, 2 infecciones superficiales, 1 movilización del cotilo, 2 ruidos, 4 aflojamientos asépticos y 2 roturas del cuello protésico); el 47,3% necesitaron revisión. La supervivencia acumulada de las prótesis fue del 97,5% (IC95%: 96,4–98,5). No encontramos diferencias en la supervivencia, en eventos adversos protésicos, en la incidencia de ruidos o luxaciones y en los resultados clínicos entre los diferentes diámetros empleados.

ConclusionesLas prótesis primarias de cadera con par de fricción cerámica-cerámica de cuarta generación han mostrado una buena supervivencia a medio plazo y buenos resultados clínicos.

In total hip arthroplasty, ceramic delta bearings are associated with minimum wear and tear rates over time, with release of particles which produce a biological tissue reaction of lower intensity compared to that of particles from the wear and tear of polyethylene.1–3 This has markedly reduced the rate of osteolysis and the failure of implants. However, first generation ceramic has been associated with 13% fracture rates of the head or the component and this rate has dropped to 5% with the development of second generation ceramic.1 The technology used to develop third generation ceramic has been able to reduce this complication to .004%.4,5 Fourth generation ceramic (Biolox®delta) is characterised by the addition of zirconium, providing greater robustness and resistance to the fracture in the laboratory,6 with the rate of this complication being .001% for head fractures and .025% for component fractures.7 Despite the reliability this ceramic bearing appears to provide, few studies report their clinical and functional outcomes with a follow-up of over 5 years. As far as we are aware only 4 studies provide information with this minimal follow-up,8–11 of which 2 are prospective.9,11 Our objective was to assess the clinical and survival rates of the primary hip prosthesis with fourth-generation ceramic bearings implanted in our centre.

Material and methodA prospective follow-up study was undertaken to analyse the clinical outcomes and the survival of the fourth-generation ceramic delta bearings (C-C) Biolox®delta (CeramTec GmbH, Plochingen, Germany). The study was approved by the ethical committee of our centre (CEIC reference 115/16) and all the patients gave their informed consent. All total primary hip prostheses implanted in our centre with a minimum follow-up of 5 years were included, or those which presented with an adverse event of interest (prosthetic review for any reasons). Between September 2008 and December 2012, 312 primary hip prostheses were undertaken in our centre and in 220 ceramic delta bearings (C-C) were used. Of the patients included in the initial sample, 205 hips (93.1%) in 205 patients were available for analysis. The causes of losses were due to ending the follow-up before 5 years had passed in 5 cases (discharge) unknown in 5 cases and death in the remaining 5 cases.

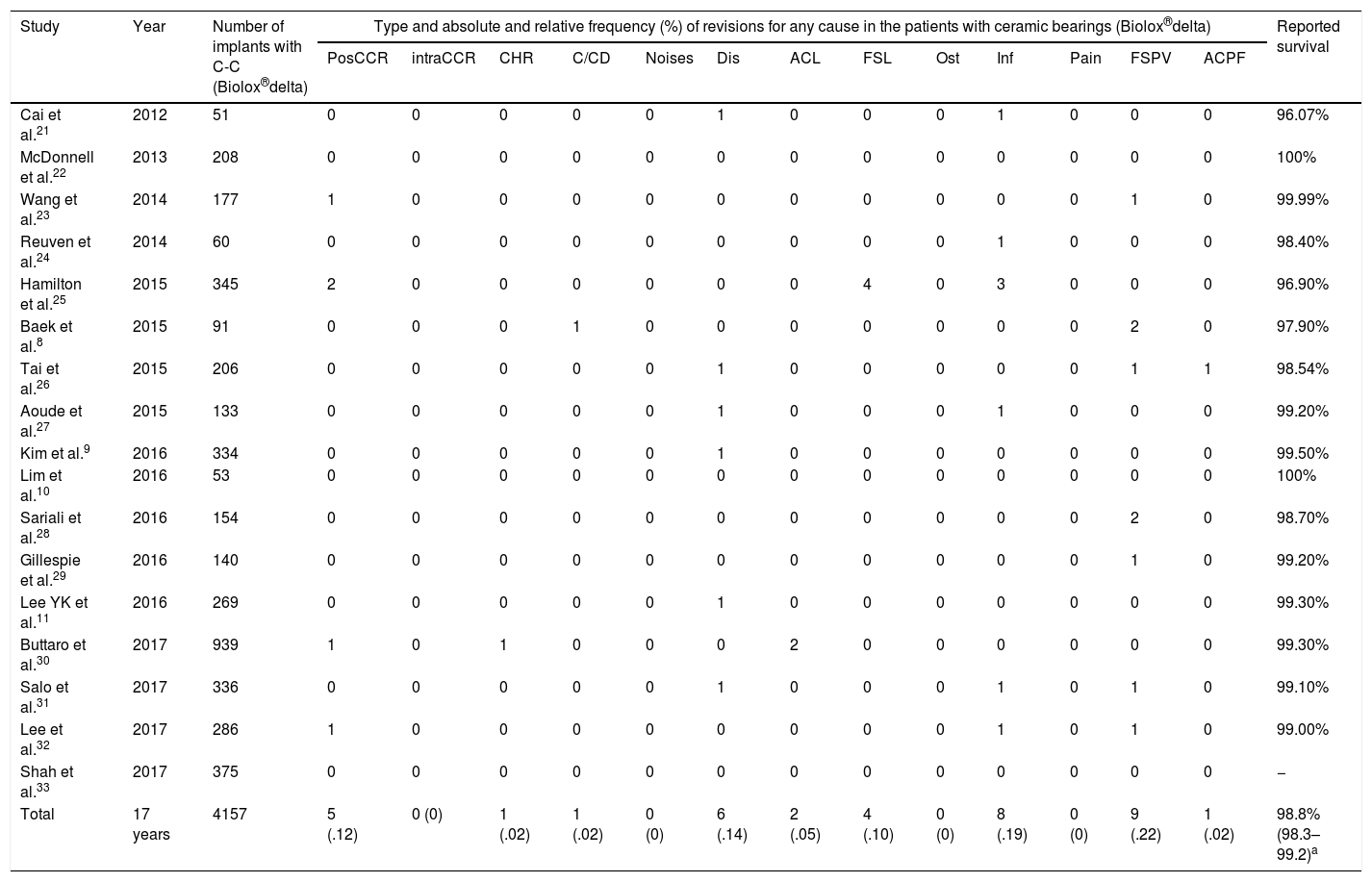

Prior to data analysis a systematic review was undertaken to assess the reported results relating to survival of the bearings (Table 1). Average reported survival was calculated through the model of random effects of DerSimonian and Laird1,2 since this statistical model accepts that the studies included in the review represent a random sample of all potentially available studies. A survival average of 98.8% (95% CI: 98.3–99.2; I2=32.6%) was obtained. A simple size for 98% survival was calculated, assuming that in our series survival would be 100%, for a statistical power of 80% and a p of .05; minimum sample size required was 189 cases.

Study relating to fourth-generation ceramic delta bearings (C-C) and reported survival.

| Study | Year | Number of implants with C-C (Biolox®delta) | Type and absolute and relative frequency (%) of revisions for any cause in the patients with ceramic bearings (Biolox®delta) | Reported survival | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PosCCR | intraCCR | CHR | C/CD | Noises | Dis | ACL | FSL | Ost | Inf | Pain | FSPV | ACPF | ||||

| Cai et al.21 | 2012 | 51 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 96.07% |

| McDonnell et al.22 | 2013 | 208 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% |

| Wang et al.23 | 2014 | 177 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 99.99% |

| Reuven et al.24 | 2014 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 98.40% |

| Hamilton et al.25 | 2015 | 345 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 96.90% |

| Baek et al.8 | 2015 | 91 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 97.90% |

| Tai et al.26 | 2015 | 206 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 98.54% |

| Aoude et al.27 | 2015 | 133 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99.20% |

| Kim et al.9 | 2016 | 334 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99.50% |

| Lim et al.10 | 2016 | 53 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% |

| Sariali et al.28 | 2016 | 154 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 98.70% |

| Gillespie et al.29 | 2016 | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 99.20% |

| Lee YK et al.11 | 2016 | 269 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99.30% |

| Buttaro et al.30 | 2017 | 939 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99.30% |

| Salo et al.31 | 2017 | 336 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 99.10% |

| Lee et al.32 | 2017 | 286 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 99.00% |

| Shah et al.33 | 2017 | 375 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − |

| Total | 17 years | 4157 | 5 (.12) | 0 (0) | 1 (.02) | 1 (.02) | 0 (0) | 6 (.14) | 2 (.05) | 4 (.10) | 0 (0) | 8 (.19) | 0 (0) | 9 (.22) | 1 (.02) | 98.8% (98.3–99.2)a |

ACl: acetabular CUP loosening; FSL: femoral stem loosening; C/CD: component/cup dislocation; Pain: pain with no fixed cause; ACPF: periprosthetic acetabular cup rupture; FSPF: femoral stem periprosthetic fracture; Inf: deep infection; Dis: dislocation; Ost: osteolysis; CHR: ceramic head rupture; intraCCR: intraoperative ceramic component rupture; PosCCR: postoperative ceramic component rupture; Noises: noises, any type.

The patients selected to use the ceramic delta bearings (C-C) were usually under 65 years of age, although no inclusion protocol was followed and the surgeon was able to take other factors into consideration such as physical activity, associated comorbidity and weight when choosing the ceramic bearings.

The patients were operated on by 5 experienced surgeons. Surgery was performed under spinal anaesthesia in 151 (73.7%) cases and under general anaesthesia in 54 (26.3%) cases. Posterolateral approach was used in 199 (97.1%) cases and anterolateral in 6 (2.9%) cases. When posterolateral approach was used we proceeded with the reconstruction of posterior soft tissues. Antibiotic prophylaxis was performed with first generation cephalosporin for 24h and thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin for one month. All patients adhered to the same postoperative rehabilitation protocol. Weight-bearing, when tolerated, was allowed the day after surgery with the help of a walking frame.

AssessmentsClinical and radiologic assessments were made by two independent observers who had not participated in surgery. No concordance analysis was made between them.

Clinical assessments were made preoperatively and postoperative at 3, 6, 12, 24months and then annually. The functional result was assessed in each annual visit using the Harris Hip Score (HHS),13 which was classified as excellent (90–100 points), good (80–89 points), average (70–79 points) or poor (69 points or under). Quality of life was obtained using the Short-Form 36 (SF-36)14 and the Western Ontario y McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)15 questionnaires, both of which had been validated for Spain. Pain was measured using the visual analogue scale (VAS) of 0 (no pain) to 10 (maximum pain). For analysis of results only the presurgical results were considered and those after 5 years of follow-up.

The radiologic study included an anteroposterior and lateral projection of the hip which had been operated on. Orientation of the acetabular component was assessed using the modified Lewinnek et al.16 model. Loosening of the acetabular component was assessed using the DeLee and Charnley17 classification. It was considered that this existed, for a continuous radiolucent line of over 1mm, osteolysis or migration of under 2mm18 or a change in direction of over 2 degrees. The loosening of the femoral component was assessed using the Gruen et al.19 areas. It was considered that this existed where there was a continuous radiolucent line of over 2mm, osteolysis, progressive collapse of over 5mm or progressive change in position of 3 degrees or more.20

Adverse events related to the ceramic delta bearings were reported in accordance with their diameter, with particular attention paid to prosthetic dislocations and the presence of noises. Assessment of the latter was not made using any type of questionnaire but by communicating with the patients and getting them to reproduce the sounds when consulted.

Statistical analysisThe distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A comparison of the categorical variables was undertaken using the exact Fisher test and the likelihood ratio test. The Mann–Whitney U test or the Kruskal–Wallis test were used for continuous variables. Post hoc comparisons were undertaken by adjusted pairs according to the Bonferroni method. For intragroup comparisons (preoperative versus postoperative) the Student's paired t test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to assess accumulated survival with the end point as prosthetic revision for any reasons. Comparisons were undertaken according to the diameter of the head used with the Breslow test. The results of the continuous variables were presented as a mean with their standard deviation and 95% confidence interval, those of nominal variables were presented as an absolute number and percentage. Statistical significance was considered as p values below .05 in all tests. The 2010 Excel programmes were used for data collection and for the creation of tables, SPSS v.22 for making comparisons, MedCalc v.13 for application of the DerSimonian and Laird method, Stata v.12 for sample calculation.

ResultsSample characteristicsThe sample consisted of 79 women and 126 men, with a mean age of 62.8±10.6 (95% CI: 61.4–64.3) years. One hundred operations were for the right hip and 105 for the left. Thirty eight patients (18.5%) had been previously operated on for the contralateral hip. The BMI of patients included in the study was 28.8±5.2 (95% CI: 28.1–29.5) kg/m2. Diagnosis was primary osteoarthritis in 197 (96.1%) cases, femoral neck fracture in 4 (2%), osteonecrosis of the femoral head in 2 (1%), hip dysplasia in 1 (.5%), and femoral epiphysiolysis sequelae in 1 (.5%). The ASA classification was 1 in 16.8%, 2 in 65.9% and 3 in 17.3% of cases. Mean follow-up 6.4±1.3 (95% CI: 6.2–6.6) years.

Characteristics of the prosthetic systems usedThe hip stems had a modular neck in 178 (86.8%) occasions: 167 H-MAX-M (Lima, San Danielle, Italy) and 11 F2L (Lima, San Danielle, Italy); and no modular neck in 27 (13.2%) occasions: 15 QUADRA-H (Medacta, Chicago, USA) and 12 H-MAX-S (Lima, San Danielle, Italy). The acetabular component was cementless in all cases. In 175 (85.4%) it was coated with hydroxyapetite (HA), 152 Delta PF (Lima, San Danielle, Italy), 23 VersaFit (Medacta, Chicago, USA) and 30 (14.6%) Delta TT (Lima, San Danielle, Italy) were of porous metal. The head diameter was 28mm in 10 (4.9%) cases, 32mm in 61 (29.8%), 36mm in 129 (62.9%) and 40mm in 5 (2.4%).

Overall resultsClinical assessment. The presurgical functional result measured through the HHS was 41.7±14.2 (95% CI: 39.7–43.7) points and the postsurgical results after 5 years were 89.6±7.1 (95% CI: 88.6–90.6) points, p<.001. Outcome relating to quality of life measured with the SF36 passed from 40.3±15.9 (95% CI: 38.1–42.5) to 81.5±14.8 (95% CI: 79.4–83.5) points, p< 001. The WOMAC scale result passed from 56.3±14.5 (95% CI: 54.3–58.4) to 8.1±9.2 (95% CI: 6.8–9.4) points, p<.001. Headaches valued on the VAS passed from 7.5±1.7 (95% CI: 7.3–7.7) to 1.3±1.5 (95% CI: 1.1–1.5) points, p<.001.

Radiologic assessment. The mean inclination angle of the acetabular cup was 44.7±7.0 (95% CI: 43.8–45.7) degrees and the mean anteversion angle of the acetabular cup was 29.7±7.0 (95% CI: 28.8–30.7) degrees. Sixteen patients (8.2%) presented with radiolucency around the acetabluar cup: 6 in region 1, 7 in region 2, 3 in region 3, and one in regions 1, 2 and 3. One patient (0.4%) presented with loosening of the acetabular component with mobilisation of the cup and this was revised.

Twenty seven patients (13.1%) presented with radiolucency around the stem: in region 1 (22) and in regions 1 and 7 (5). Out of these, 4 patients (1%) presented with radiologic criteria of loosening of the femoral component and were revised.

The remaining patients presented with signs of osteointegration of the prosthetic components. We did not observe any signs of osteolysis in any patients.

Nineteen adverse events relating to the prostheses were reported: 4 (1.9%) were periprosthetic fractures, 2 of which were operated on again and 2 were from falls; 4 (1.9%) dislocations; 2 superficial infections (1%); 1 cup migration (.5%); 2 clicking noises from the prostheses; 4 (1.9%) aseptic loosening and 2 (1%) prosthetic modular neck ruptures. Both neck ruptures presented in male patients, who were overweight and led an active life; the neck in both cases was made of titanium and was of L length in one case and S length in the other. In both cases the heads used were cut. Out of these 19 patients, 9 (47.3%) required revision surgery. None of the ceramic components broke.

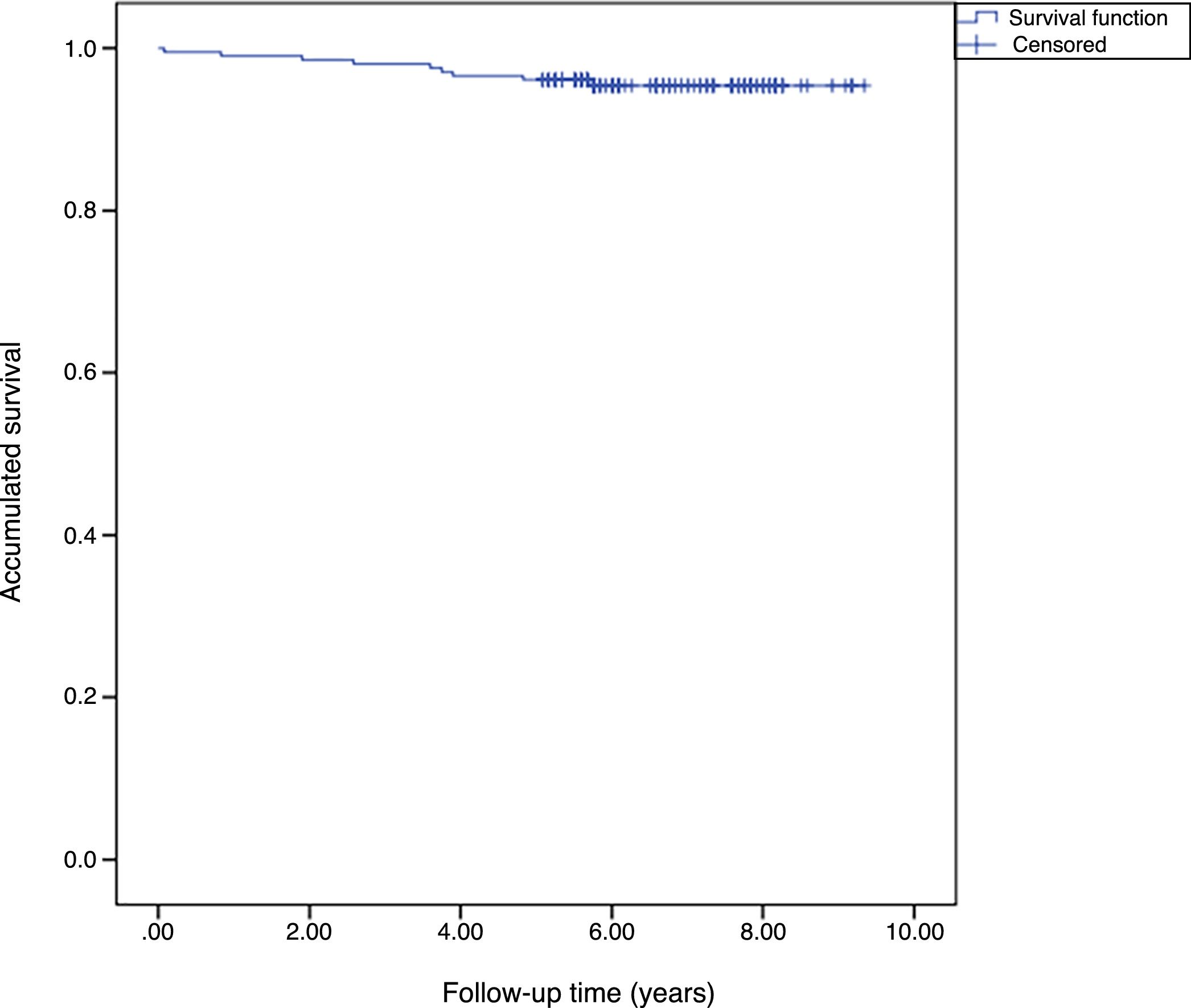

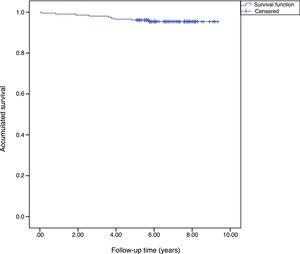

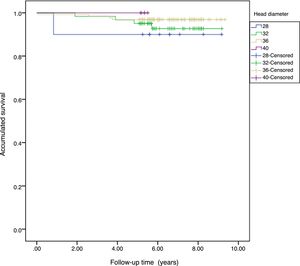

The accumulated survival of the prostheses included in the sample was 97.5% (95% CI: 96.4–98.5) (Fig. 1).

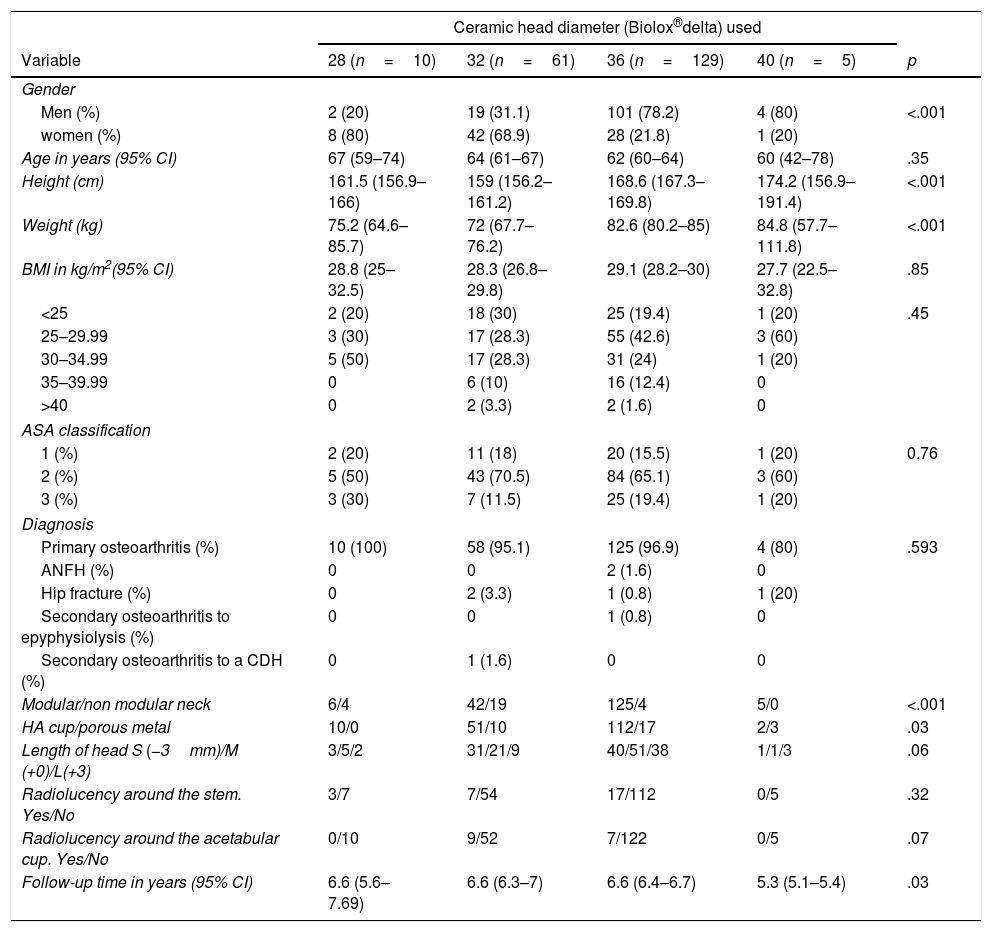

Outcomes according to the head diameter usedBaseline characteristics. The groups were different with regards to gender distribution (32mm vs 36mm, p<.001), with the greatest use of 32mm heads in the women (68.9%) versus the men (31.1%) and of 36mm heads in the men (78.2%) versus the women (21.8%). Differences were also found with regard to the size (32 vs 36, p<.001; 32 vs 40, p=.02; 28 vs 36, p=.36), weight (32 vs 36; p<.001), type of stem used (depending on the modularity of the neck, 32mm vs 36mm, p<.001), type of cup used (according to type of coating for the pressfit, 28mm vs 40mm, p=.02) and follow-up time, although the minimum follow-up time of them all was 5 years. All these differences may be found summarised in Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the simple according to head diameter used.

| Ceramic head diameter (Biolox®delta) used | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 28 (n=10) | 32 (n=61) | 36 (n=129) | 40 (n=5) | p |

| Gender | |||||

| Men (%) | 2 (20) | 19 (31.1) | 101 (78.2) | 4 (80) | <.001 |

| women (%) | 8 (80) | 42 (68.9) | 28 (21.8) | 1 (20) | |

| Age in years (95% CI) | 67 (59–74) | 64 (61–67) | 62 (60–64) | 60 (42–78) | .35 |

| Height (cm) | 161.5 (156.9–166) | 159 (156.2–161.2) | 168.6 (167.3–169.8) | 174.2 (156.9–191.4) | <.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 75.2 (64.6–85.7) | 72 (67.7–76.2) | 82.6 (80.2–85) | 84.8 (57.7–111.8) | <.001 |

| BMI in kg/m2(95% CI) | 28.8 (25–32.5) | 28.3 (26.8–29.8) | 29.1 (28.2–30) | 27.7 (22.5–32.8) | .85 |

| <25 | 2 (20) | 18 (30) | 25 (19.4) | 1 (20) | .45 |

| 25–29.99 | 3 (30) | 17 (28.3) | 55 (42.6) | 3 (60) | |

| 30–34.99 | 5 (50) | 17 (28.3) | 31 (24) | 1 (20) | |

| 35–39.99 | 0 | 6 (10) | 16 (12.4) | 0 | |

| >40 | 0 | 2 (3.3) | 2 (1.6) | 0 | |

| ASA classification | |||||

| 1 (%) | 2 (20) | 11 (18) | 20 (15.5) | 1 (20) | 0.76 |

| 2 (%) | 5 (50) | 43 (70.5) | 84 (65.1) | 3 (60) | |

| 3 (%) | 3 (30) | 7 (11.5) | 25 (19.4) | 1 (20) | |

| Diagnosis | |||||

| Primary osteoarthritis (%) | 10 (100) | 58 (95.1) | 125 (96.9) | 4 (80) | .593 |

| ANFH (%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.6) | 0 | |

| Hip fracture (%) | 0 | 2 (3.3) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (20) | |

| Secondary osteoarthritis to epyphysiolysis (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 | |

| Secondary osteoarthritis to a CDH (%) | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | |

| Modular/non modular neck | 6/4 | 42/19 | 125/4 | 5/0 | <.001 |

| HA cup/porous metal | 10/0 | 51/10 | 112/17 | 2/3 | .03 |

| Length of head S (−3mm)/M (+0)/L(+3) | 3/5/2 | 31/21/9 | 40/51/38 | 1/1/3 | .06 |

| Radiolucency around the stem. Yes/No | 3/7 | 7/54 | 17/112 | 0/5 | .32 |

| Radiolucency around the acetabular cup. Yes/No | 0/10 | 9/52 | 7/122 | 0/5 | .07 |

| Follow-up time in years (95% CI) | 6.6 (5.6–7.69) | 6.6 (6.3–7) | 6.6 (6.4–6.7) | 5.3 (5.1–5.4) | .03 |

CDH: congenital dysplasia of the hip; HA: hydroxiapatite; BMI: body mass index; ANFH: avascular necrosis of the femoral head.

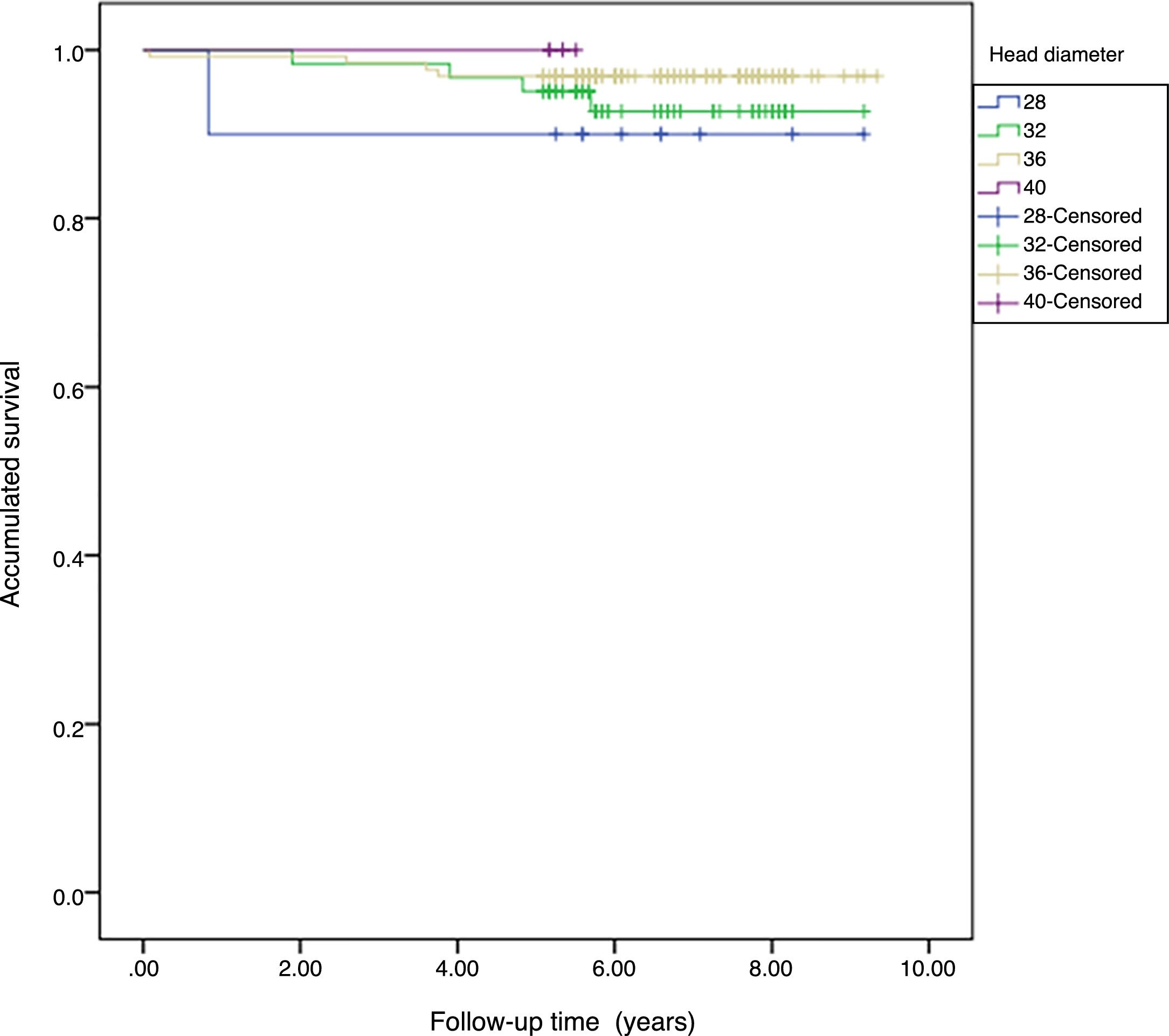

Survival. The accumulated survival for the 28mm diameter was 90%, for the 32mm 95.7% (95% CI: 91.8–99.5), for the 36mm 98.6% (95% CI: 96.4–99.6) and for the 40mm 100%. We found no statistical differences between the group survival, p=.571 (Fig. 2).

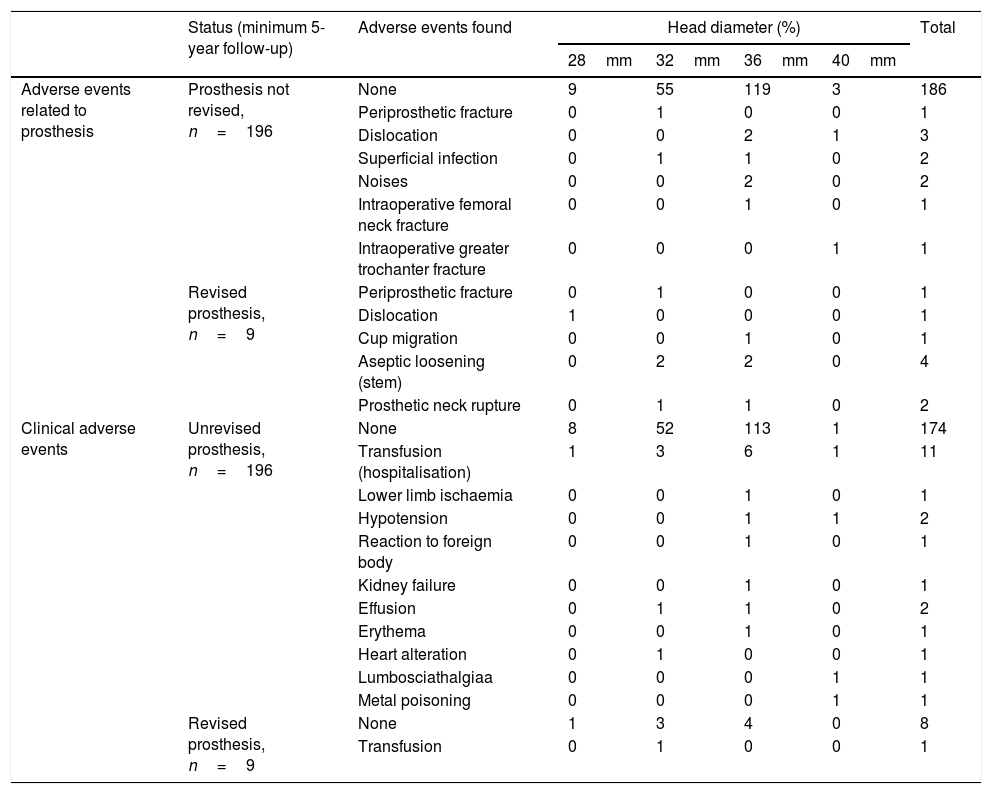

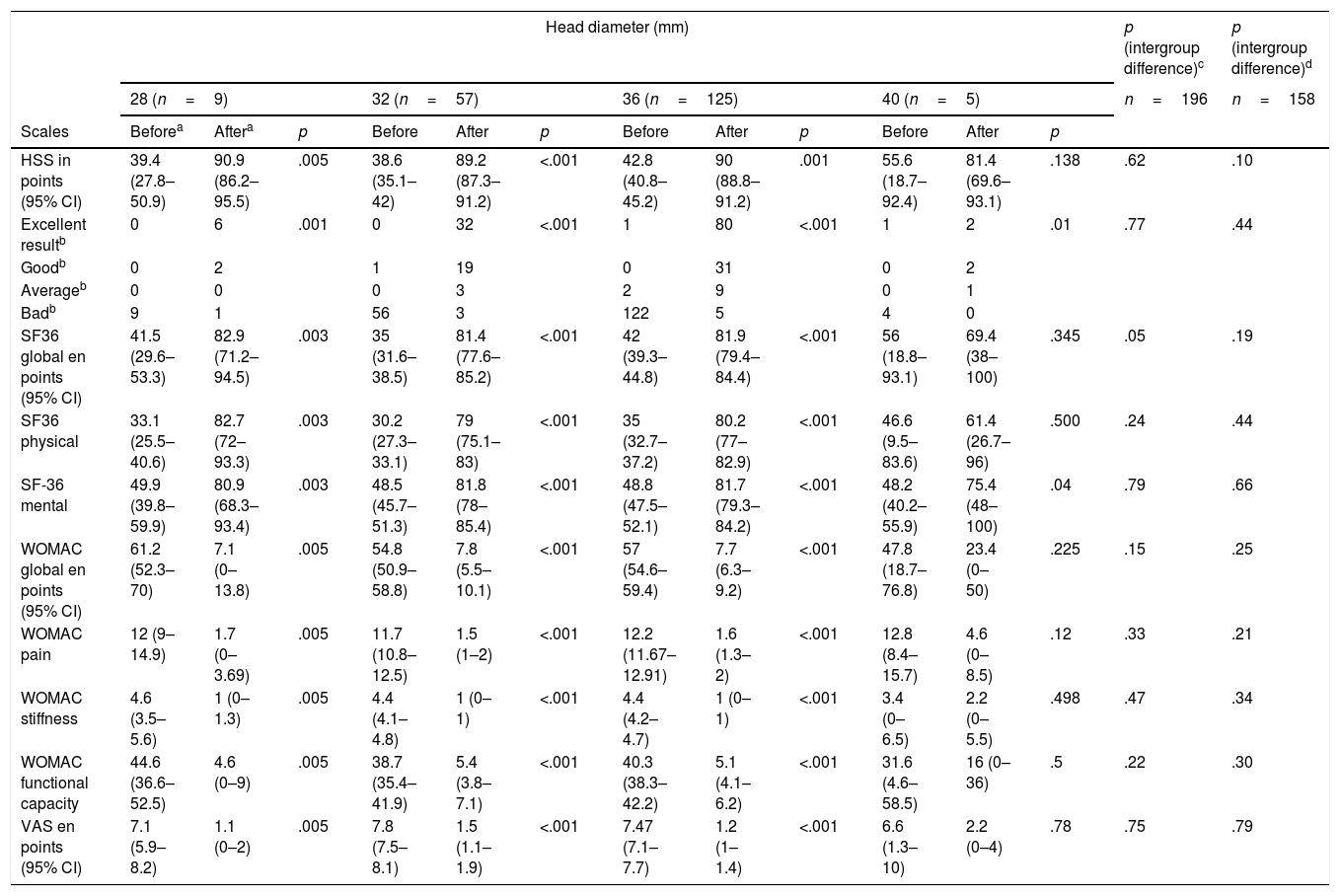

Clinical assessment. The 32mm and 36mm diameter groups differ regarding their previous functional state through the SF-36 (p=.01) questionnaire, and particularly in its physical scale (p=.049), and the mean difference was 4.8 points. In intragroup assessment only the 40mm diameter did not present with any improvement in the assessed parameters, although we considered that this was due to intraoperative complications in one case (greater trochanter fracture which required osteosynthesis with poor outcome, although the patient had not wished to undergo another operation) and medical complications in 2 cases: one patient presented with lumbosciatic pain prior to surgery and another presented with signs of metal poisoning (miocardiopathy and constitutional syndrome, with serum chromium levels of 50.7μg/l and of cobalt of 551μg/l). We should highlight that this patient had a resurfacing prosthesis in the contralateral hip with metal bearings which had already been revised (Table 3). On comparing the final clinical outcome we found no differences regarding the different diameters of the heads used (Table 4).

Adverse events found in the simple according to the head diameter used.

| Status (minimum 5-year follow-up) | Adverse events found | Head diameter (%) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28mm | 32mm | 36mm | 40mm | ||||

| Adverse events related to prosthesis | Prosthesis not revised, n=196 | None | 9 | 55 | 119 | 3 | 186 |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Dislocation | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Superficial infection | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Noises | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Intraoperative femoral neck fracture | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Intraoperative greater trochanter fracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Revised prosthesis, n=9 | Periprosthetic fracture | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Dislocation | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Cup migration | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Aseptic loosening (stem) | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 4 | ||

| Prosthetic neck rupture | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Clinical adverse events | Unrevised prosthesis, n=196 | None | 8 | 52 | 113 | 1 | 174 |

| Transfusion (hospitalisation) | 1 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 11 | ||

| Lower limb ischaemia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Hypotension | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Reaction to foreign body | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Kidney failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Effusion | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Erythema | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Heart alteration | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Lumbosciathalgiaa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Metal poisoning | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Revised prosthesis, n=9 | None | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 8 | |

| Transfusion | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

Clinical results of the patients who survived in accordance with the diameter of the head used at 5 years follow-up.

| Head diameter (mm) | p (intergroup difference)c | p (intergroup difference)d | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 (n=9) | 32 (n=57) | 36 (n=125) | 40 (n=5) | n=196 | n=158 | |||||||||

| Scales | Beforea | Aftera | p | Before | After | p | Before | After | p | Before | After | p | ||

| HSS in points (95% CI) | 39.4 (27.8–50.9) | 90.9 (86.2–95.5) | .005 | 38.6 (35.1–42) | 89.2 (87.3–91.2) | <.001 | 42.8 (40.8–45.2) | 90 (88.8–91.2) | .001 | 55.6 (18.7–92.4) | 81.4 (69.6–93.1) | .138 | .62 | .10 |

| Excellent resultb | 0 | 6 | .001 | 0 | 32 | <.001 | 1 | 80 | <.001 | 1 | 2 | .01 | .77 | .44 |

| Goodb | 0 | 2 | 1 | 19 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 2 | ||||||

| Averageb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 1 | ||||||

| Badb | 9 | 1 | 56 | 3 | 122 | 5 | 4 | 0 | ||||||

| SF36 global en points (95% CI) | 41.5 (29.6–53.3) | 82.9 (71.2–94.5) | .003 | 35 (31.6–38.5) | 81.4 (77.6–85.2) | <.001 | 42 (39.3–44.8) | 81.9 (79.4–84.4) | <.001 | 56 (18.8–93.1) | 69.4 (38–100) | .345 | .05 | .19 |

| SF36 physical | 33.1 (25.5–40.6) | 82.7 (72–93.3) | .003 | 30.2 (27.3–33.1) | 79 (75.1–83) | <.001 | 35 (32.7–37.2) | 80.2 (77–82.9) | <.001 | 46.6 (9.5–83.6) | 61.4 (26.7–96) | .500 | .24 | .44 |

| SF-36 mental | 49.9 (39.8–59.9) | 80.9 (68.3–93.4) | .003 | 48.5 (45.7–51.3) | 81.8 (78–85.4) | <.001 | 48.8 (47.5–52.1) | 81.7 (79.3–84.2) | <.001 | 48.2 (40.2–55.9) | 75.4 (48–100) | .04 | .79 | .66 |

| WOMAC global en points (95% CI) | 61.2 (52.3–70) | 7.1 (0–13.8) | .005 | 54.8 (50.9–58.8) | 7.8 (5.5–10.1) | <.001 | 57 (54.6–59.4) | 7.7 (6.3–9.2) | <.001 | 47.8 (18.7–76.8) | 23.4 (0–50) | .225 | .15 | .25 |

| WOMAC pain | 12 (9–14.9) | 1.7 (0–3.69) | .005 | 11.7 (10.8–12.5) | 1.5 (1–2) | <.001 | 12.2 (11.67–12.91) | 1.6 (1.3–2) | <.001 | 12.8 (8.4–15.7) | 4.6 (0–8.5) | .12 | .33 | .21 |

| WOMAC stiffness | 4.6 (3.5–5.6) | 1 (0–1.3) | .005 | 4.4 (4.1–4.8) | 1 (0–1) | <.001 | 4.4 (4.2–4.7) | 1 (0–1) | <.001 | 3.4 (0–6.5) | 2.2 (0–5.5) | .498 | .47 | .34 |

| WOMAC functional capacity | 44.6 (36.6–52.5) | 4.6 (0–9) | .005 | 38.7 (35.4–41.9) | 5.4 (3.8–7.1) | <.001 | 40.3 (38.3–42.2) | 5.1 (4.1–6.2) | <.001 | 31.6 (4.6–58.5) | 16 (0–36) | .5 | .22 | .30 |

| VAS en points (95% CI) | 7.1 (5.9–8.2) | 1.1 (0–2) | .005 | 7.8 (7.5–8.1) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) | <.001 | 7.47 (7.1–7.7) | 1.2 (1–1.4) | <.001 | 6.6 (1.3–10) | 2.2 (0–4) | .78 | .75 | .79 |

Radiologic assessment. When assessing the frequency of the appearance of radiolucent lines we found no differences between the groups for femoral (p=.32) and acetabular (p=.07) components.

Adverse events. The adverse events relating to each bearing are detailed in Table 3. When assessing the frequency of dislocations between the groups we found no statistically significant differences, p=.06. Evaluation of noise frequency between the groups did not reveal any statistically significant differences, p=.601, and they were no reproducible results in the surgery. We found no statistically significant differences when comparing patient groups who presented these phenomena to those who did not, with respect to baseline features and positioning of prosthetic components.

DiscussionWe prospectively studied 205 patients for whom 19 adverse events were found relating to the prosthesis and 9 of whom required revision surgery. Survival with an endpoint of prosthetic revision for any cause in our sample was 97.5% (95% CI: 96.4–98.5) at 6.14±1.85 (95% CI: 5.9–6.39) years. General clinical outcome was good at 5-year follow-up and similar to that reported by other published works8–11,21–33 (Table 1). The 40mm diameter head group presented with the poorest results, which were justified by other reasons beyond bearings. We did not find any variable associated with the development of noise or prosthetic dislocation. There were no cases of fracture of the ceramic components.

The first published study concerning fourth generation ceramic delta bearings (C-C) was by Hamilton et al.5 In this study a comparison was made with the highly cross-linked polyethylene ceramic bearing and the authors reported results of 177 C-C bearings at 2.6 (95% CI: 1.75–4.08) years of mean follow-up. The n of this study was extended and published in 2015,25 which is why we have not added the first study to Table 1. Therefore, with a mean follow-up of 5.3±1.4years, the authors report of a C-C bearing survival of 96.9% (95% CI: 94–98.4). The causes of their revisions are contained in Table 1. Similarly to their sample, we had 4 revisions due to the loosening of the femoral stem. These authors also report 9 dislocations: 6 in the 28mm group and 3 in the 36mm group; both frequencies of appearance of this complication coincide with ours: 1/10 in the 28mm group (p=.324) and 2 in the 36mm (p=.99). Furthermore, we found one dislocation in the 40mm group. They reported 26 noises (squeaking), with no differences being found between the clinical outcomes of the patients who complained about this and those who did not. They found associated factors to these were gender (women), use of 36mm diameter heads and a BMI>30kg/m2.

The noises were described as clicking and squeaking or grinding. The last two were related to ceramic insert edge overload due to over inclination of the acetabular cup.34 In our sample we found there were 2 patients who complained about noises, both with 36mm cups but we did not find any variable associated with this phenomenon. Hamilton et al.25 found there was an association between the 36mm diameter and the development of noises compared with the 28mm heads. Although the rate of noises in the series whose objective is its study8,22,26,29,31,33 is of that of 16.5% (95% CI: 9.73–24.8; I2=92.8%), in the overall series8–11,21–33 this phenomenon was not a reason for revision, and its clinical importance is under study (Table 1). Gillespie et al.29 found that in patients with noise ceramic bearing C-C hip prostheses satisfaction was lower than those patients whose prostheses made no noise. Similar results were found by McDonnell et al.22 and Salo et al.31 It would therefore be pertinent to warn patients of this risk even though it would not be a cause for revision. In one recent review where the prosthetic design traits and orientation of components in relation to the appearance of noise were described, the authors suggested the use of long, thick titanium stems, the avoidance of high rimmed cups and maintaining their orientation between 25±10degrees anteversion and 45±10degrees inclination. These strategies may reduce vibrations and the possibility of noises.35

Dislocation frequency in the published series is of 26 out of 4157 patients, .7% (95% CI: .33–1.21; I2=62.9%). Out of these 6 had to be revised, .19% (95% CI: .08–.35; I2=0%). Our data, despite appearing to be worse, did not present with any statistically significant differences for the number of dislocations p=.05) or for the number of revisions due to this cause (p=.28).

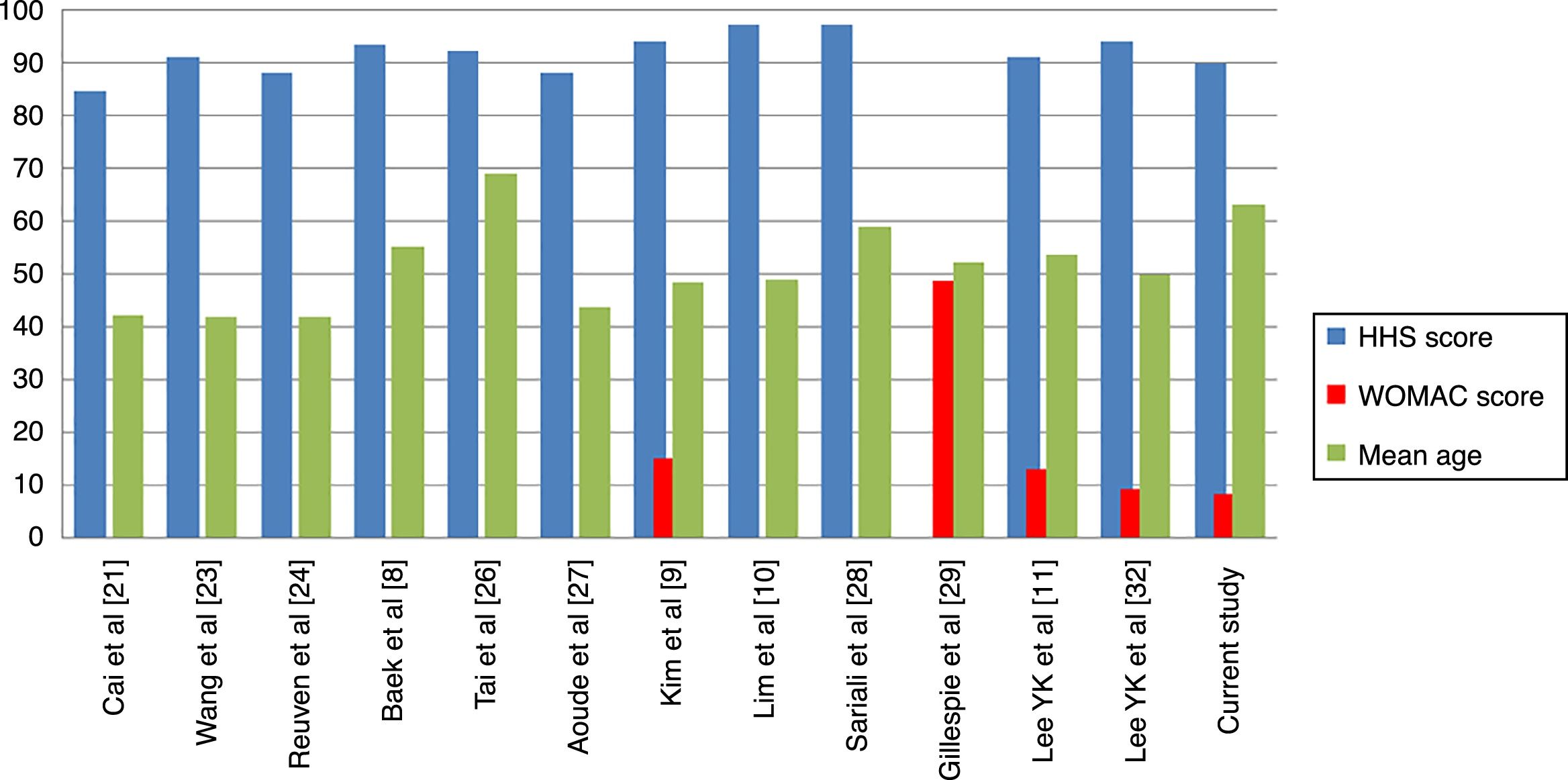

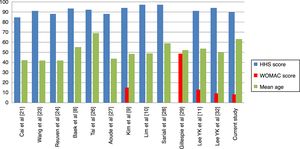

Regarding clinical outcome, ours did not differ from those previously published. When comparing the mean of published results with ours we found no differences in the results of functional capacity measured through the Harris Hip Score (p=.66) or in quality of life measured through the WOMAC (p=.50) (Table 5). We must consider that of the 12 studies11,21,23,24,26–29,32 which assess at least a similar scale to ours, in 11 the mean age of patients was under 60years. Only our study and that of Tai et al.26 have a mean age above 60 years, although when comparing results divided by this factor we did not find any statistically significant differences.

Final results reported in the literature.

| Study | Patient age | Questionnaires used for assessing results | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional results | Quality of life | Pain | ||||||||||

| HHS | UCLA | OHS | HOOS | OS | WOMAC | SF-12 | SF-36 | VR12 | RAND-36 | VAS | ||

| Cai et al.21 | 42.1±1.5 (21–60) | 84.6 | ||||||||||

| McDonnell et al.22 | 59 (22–84) | |||||||||||

| With noises | 56 (23–73) | 6.84 (3–10) | 41 (22–48) | 79 (25–100) | 50.5 (24–63) | |||||||

| Without noises | 60 (22–84) | 6.7 (0–10) | 42 (8–48) | 86.4 (9.8–100) | 51.5 (15–67) | |||||||

| Wang et al.23 | 41.8±8.3 (22–55) | 91.0±5.1 | ||||||||||

| Reuven et al.24 | 41.8 (21–56) | 88 (40–90) | 6 (2–10) | |||||||||

| Hamilton et al.25 | (20–75) | |||||||||||

| 28mm | 56.4±10.6 | 94.5±9.9 | ||||||||||

| 36mm | 57.3±11 | 93.7±10.2 | ||||||||||

| Baek et al.8 | 55±14 | 93.2±6.8 | ||||||||||

| Tai et al.26 | 69 (38.1–93) | 92 (44–100) | ||||||||||

| Aoude et al.27 | 43.6 (14–65) | 88.1±13.6 (32–99) | 6.2±1.9 (2–10) | |||||||||

| Kim et al.9 | 48.2±11.3 (21–49) | 94±6.1 (70–100) | 8.6 (8–10) | 15±8 (5–25) | ||||||||

| Lim et al.10 | 49 (20–80) | 97 (78–100) | ||||||||||

| Sariali et al.28 | 58.8±13.5 (18–84) | 97±7 (59–100) | 57±6 (37–60) | |||||||||

| Gillespie et al.29 | 52 (16–76) | 40.8 | 48.5 | 38.2 | ||||||||

| Lee et al.11 | 53.7 (17–75) | 91 (41–100) | 4.6 (2–9) | 12.9±14.9 (4–37) | ||||||||

| Buttaro et al.30,a | 49 (17–82.7) | |||||||||||

| Salo et al.31 | 61 (29–78) | 46 [41–48] | 76 [57–88] | |||||||||

| With noises | 58 (32–72) | 43 [36–47] | 72 [48–85] | |||||||||

| Without noises | 61 (29–78) | 46.5 [42–48] | 76 [57–89] | |||||||||

| Lee et al.32 | 49.7 (16–83) | 93.8±7.6 | 6.2±1.9 | 9.3±10.8 | ||||||||

| Shah et al.33,b | − | |||||||||||

| Conventional | 67.2±9.4 | |||||||||||

| Navigated | 58.3±9.1 | |||||||||||

| Current study | 63±10.6 (24–85) | 89.6±7.2 (65–100) | 8.3±9.2 (0–57) | 81.5±14.8 (26–100) | 1.3±1.5 (0–7) | |||||||

| 28mm | 67±10.9 | 90.9±6.5 (80–99) | 7.1±9.5 (0–25) | 82.9±16.2 (46–97) | 1.1±1.3 (0–4) | |||||||

| 32mm | 64±10.6 | 89.2±7.6 (65–100) | 7.8±8.8 (0–40) | 81.4±14.8 (26–100) | 1.5±1.6 (0–7) | |||||||

| 36mm | 62±10.4 | 90±6.8 (70–100) | 7.7±8.3 (0–32) | 81.9±14.3 (38–100) | 1.2±1.4 (0–5) | |||||||

| 40mm | 60±14.4 | 81.4±9.4 (70–92) | 23.4±21.4 (3–57) | 69.4±25.2 (29–90) | 2.2±1.4 (0–4) | |||||||

VAS: visual analogue scale of pain; HOOS: Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; HHS: Harris Hip Score; OHS: Oxford Hip Score; OS: Oxford quality of life score; RAND-36: Research and Development 36-item health survey 1.0); SF-12: Short Form 12; SF-36: Short Form 36; UCLA: University of California at Los Angeles: Activity Score; VR12: Veterans Rand 12-Item health survey; WOMAC: The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

In our study we found no statistically significant differences in the intragroup clinical assessment (before/after surgery) regarding the head diameter used. We observed that in the 40mm diameter patients did not improve. As previously stated, these results are probably related to complications other than bearings. Only Tai et al.26 and Salo et al.31 report on the use of 40mm or larger ceramic heads, but they do not report clinical outcomes for these specifically, and we are therefore unable to compare our results. Hamilton et al.25 compare the presurgical and postsurgical clinical results of the 28mm (177cases) and 36mm (168) heads, obtaining significant improvements in intragroup comparisons and no differences in intergroup comparisons. Their results are comparable to ours for heads of 28mm (HHS, p=.28), although they are better for heads of 36mm (HHS, +3.7points; 95% CI: 1.7–5.6; p<.001). it is difficult to establish the causes of the differences between the samples due to variations of methodology, follow-up and prosthetic systems used (Table 5, Fig. 3).

It is important to note the large number of modular necks used in our sample. The decision for their use makes the surgeon legally responsible for the construct. In our sample there were two titanium modular neck ruptures and we would suggest not using this type of neck in active, overweight patients.

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample was calculated to obtain sufficient power to establish adequate assessment of survival, but not to find differences in the clinical results between the different diameters. Secondly, in 96% of our cases the initial diagnosis recorded was primary hip osteoarthritis, and therefore the resulting severity of the deformity or the bone characteristics hinder extrapolation of results to other diagnoses. Thirdly, the groups with 28mm and 40mm heads are very small and it is difficult to interpret and extrapolate their results. Fourthly, depending on the diameter of the head used, the groups used presented differences with regards to their baseline and prosthetic characteristics. Four types of stems and 3 types of cups were used, without their frequency of use being homogeneously distributed. We consider that this may affect the interpretation of results. Fifthly, despite follow-up of over 5years, results are still mid-term and greater follow-up needs to be gained to determine the safety and durability of fourth-generation ceramic delta (C-C) bearing prostheses.

ConclusionsPrimary hip prostheses with fourth-generation ceramic bearings showed good survival in the medium term and good clinical results.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence II.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that for this investigation no experiments were carried out on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors did not receive any financial assistance with any of this study. Neither did they sign any agreement by which they would receive profits or fees from any business entity. The foundations, educational establishments and other non-profitmaking organisations to which the authors are affiliated are not paid nor will be paid by any business entity.

Please cite this article as: Novoa-Parra CD, Pelayo-de Tomás JM, Gómez-Aparicio S, López-Trabucco RE, Morales-Suárez-Varela M, Rodrigo-Pérez JL. Prótesis total de cadera primaria con par de fricción cerámica sobre cerámica de cuarta generación: resultados clínicos y de supervivencia con un seguimiento mínimo de 5 años. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:110–121.