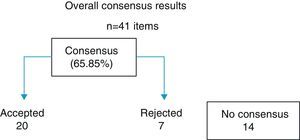

A consensus, prepared by SECOT, is presented on the management of medial knee compartment osteoarthritis, in order to establish clinical criteria and recommendations directed at unifying the criteria in its management, dealing with the factors involved in the pathogenesis of medial femorotibial knee osteoarthritis, the usefulness of diagnostic imaging techniques, and the usefulness of arthroscopy. Conservative and surgical treatments are also analyzed. The experts consulted showed a consensus (agreed or disagreed) in 65.8% of the items considered, leaving 14items where no consensus was found, which included the aetiopathogenesis of the osteoarthritis, the value of NMR in degenerative disease, the usefulness of COX-2 and the chondroprotective drugs, as well as on the ideal valgus tibial osteotomy technique.

Se presenta un consenso elaborado por SECOT sobre la actuación en la artrosis del compartimento medial de la rodilla para establecer criterios y recomendaciones clínicas orientadas a unificar criterios en su manejo, abordando los factores implicados en la patogenia de la artrosis femorotibial medial de rodilla, la utilidad de las técnicas diagnósticas por la imagen y la utilidad de la artroscopia. También se analizarán los tratamientos conservadores y el tratamiento quirúrgico. Los expertos consultados muestran consenso (acuerdo o desacuerdo) en el 65,85% de los ítems planteados, dejando 14ítems donde no se encontró el consenso que se enmarcaron en la etiopatogenia de la artrosis, el valor de la RM en la patología degenerativa, la utilidad de los COX-2 y de los fármacos condroprotectores, así como sobre la técnica idónea de la osteotomía valguizante.

Osteoarthritis of the knee has great impact on healthcare services, with its prevalence in the Spain population aged over 60 years being 12.2% (14.9% in women and 8.7% in men).1 Articular degeneration of the medial knee compartment has been considered as a differentiated phenotype, given that it is a lesion located in the anteromedial quadrant, with the cartilage of the posterior third preserved and with a mirror alteration in the cartilage of the medial femoral condyle.2 The existence of genetic factors in the development of this disease has been demonstrated in twins.3

In clinical practice, there are various approaches to the patient with osteoarthritis of the medial compartment of the knee, in both diagnosis and treatment. For that reason, it was considered of interest to reach a consensus to establish clinical criteria and recommendations aimed at unifying criteria in its management, addressing the factors involved in the pathogenesis of medial femorotibial osteoarthritis of the knee and the usefulness of diagnostic techniques. Conservative treatments (rehabilitation, analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] and chondroprotective agents) will also be analyzed, as well as surgical treatment (addition valgus osteotomy versus that of subtraction, unicompartmental prosthesis and total prosthesis).

MethodThe modified Delphi method is a reliable, wide-spread procedure for achieving professional consensus from groups of experts (in our case, 41) through 2 successive rounds of surveys, with structured response scales that facilitate visual and statistical analysis of the distribution of group opinions. Exposing the intermediate results among the experts makes it possible to evaluate the criteria that separate from the group individually and reconsider personal opinions, bringing initially divergent postures closer together. The Delphi method is reliable and experienced and has been improved since its development in the 1970s by the Rand Corporation (Palo Alto University, CA, USA); it has a long tradition of application in medicine, being used to achieve consensus in a heterogeneous group of experts on a subject of interest submitted to variability of criteria or to professional controversy. The method makes it possible to explore prior opinions and reach professional consensus in a geographically disperse group of experts, avoiding the inconveniences of in-person consensus conferences (cost, trips, influence biases, predominance of leaders, lack of confidentiality, etc.) on the subject under study by means of successive rounds of a closed-response structured survey, with processing and information on the intermediate results. Its strengths are the anonymity of individual opinions during development, controlled interaction among the group, opportunity for reflection and reconsideration of postures, and the statistical validation of the consensus achieved.

The method of development followed for this consensus was to carry out 2 successive rounds of the same questionnaire, with a semi-qualitative structured survey and processing and diffusion of the intermediate results. These were the stages of elaboration we followed: (1) Constitution of the scientific committee, which was in charge of the literature review and the formulation of recommendations for debate. (2) Constitution of the panel of experts, who were professionals of whom opinion was requested during the process. (3) Diffusion of the questionnaire in 2 successive rounds with intermediate processing of opinions and report to the panelists. (4) Preparation of the consensus document.

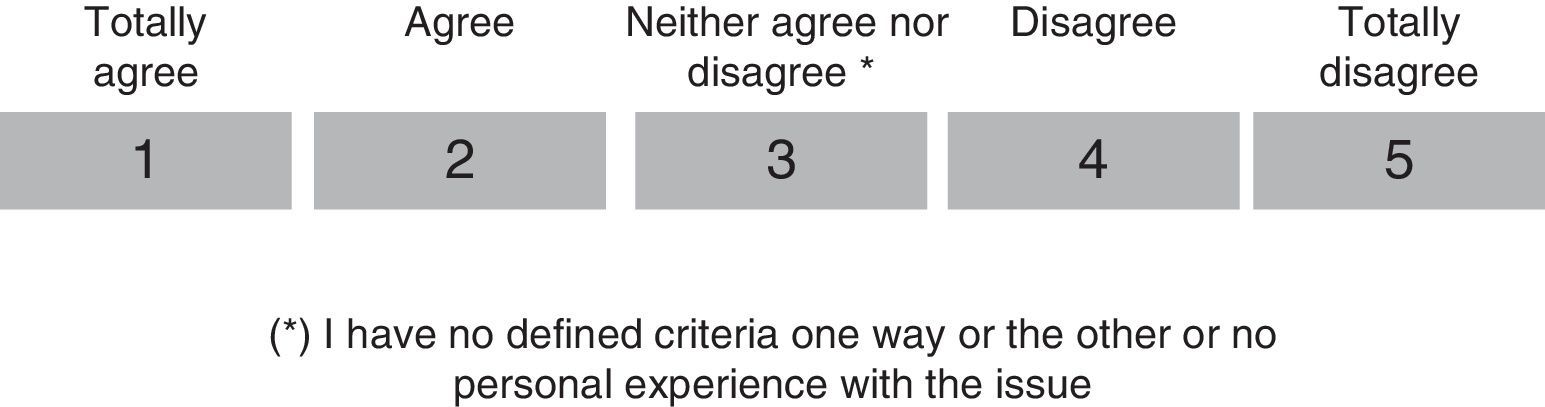

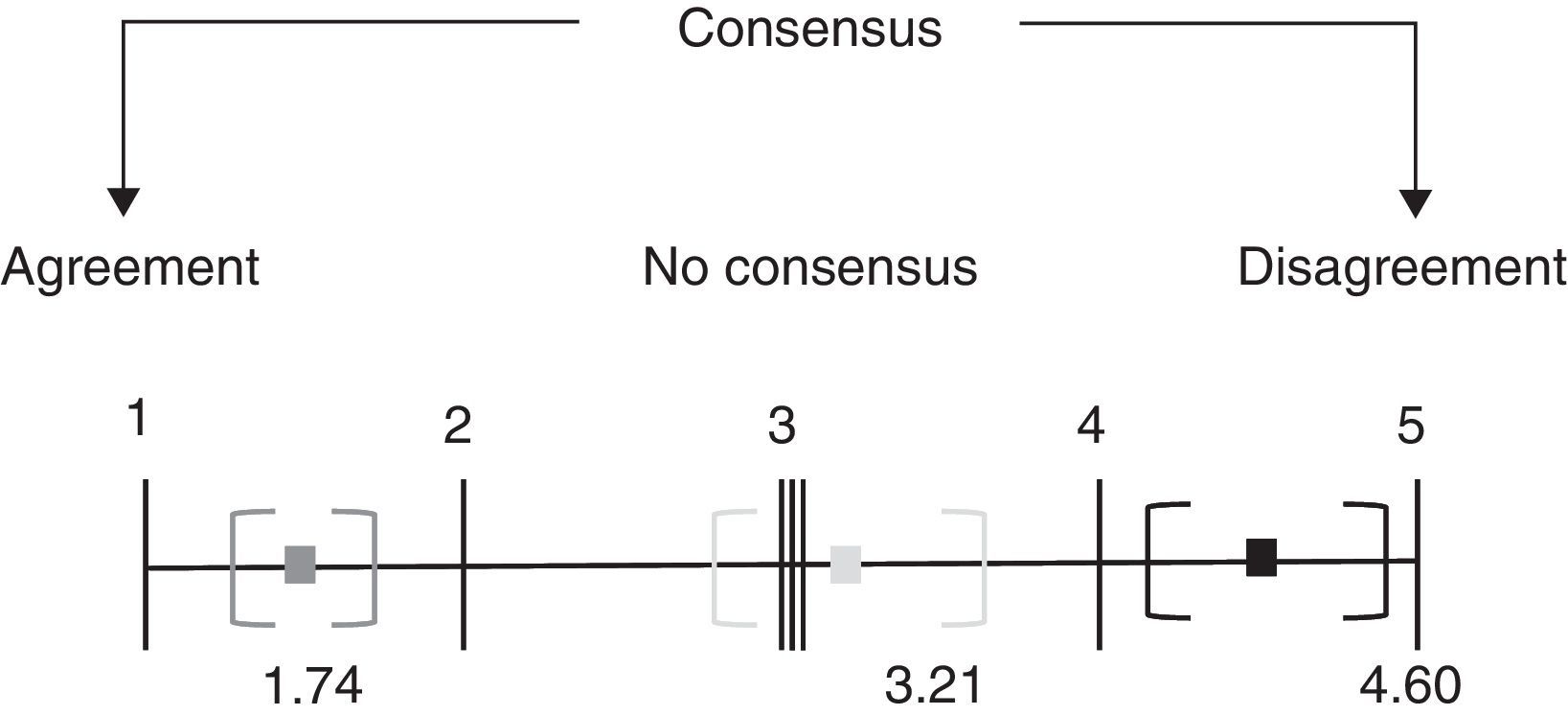

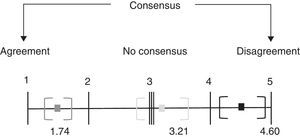

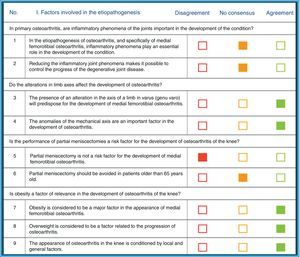

The Likert scale (Fig. 1) was used to score the different items and the analysis of the responses for each item; the average of the scores for the group was obtained and the 95% confidence interval (CI 95%) was constructed. The smaller the average (the closer to 1), the greater the agreement in the group with the item proposed. The larger the average (the closer to 5), the greater the disagreement in the group with the item proposed. If the CI 95% of the average encompassed the value 3, this meant that the group failed to achieve a unanimous consensus in one direction or another. The smaller the confidence interval, the greater the unanimity existing in the opinions of the group (Fig. 2). For items in which no consensus was achieved after circulating the survey twice, the distribution of the responses was analyzed to check whether there were markedly different opinions among the panelists or whether the majority of the group indicated that they had insufficient criteria on the item.

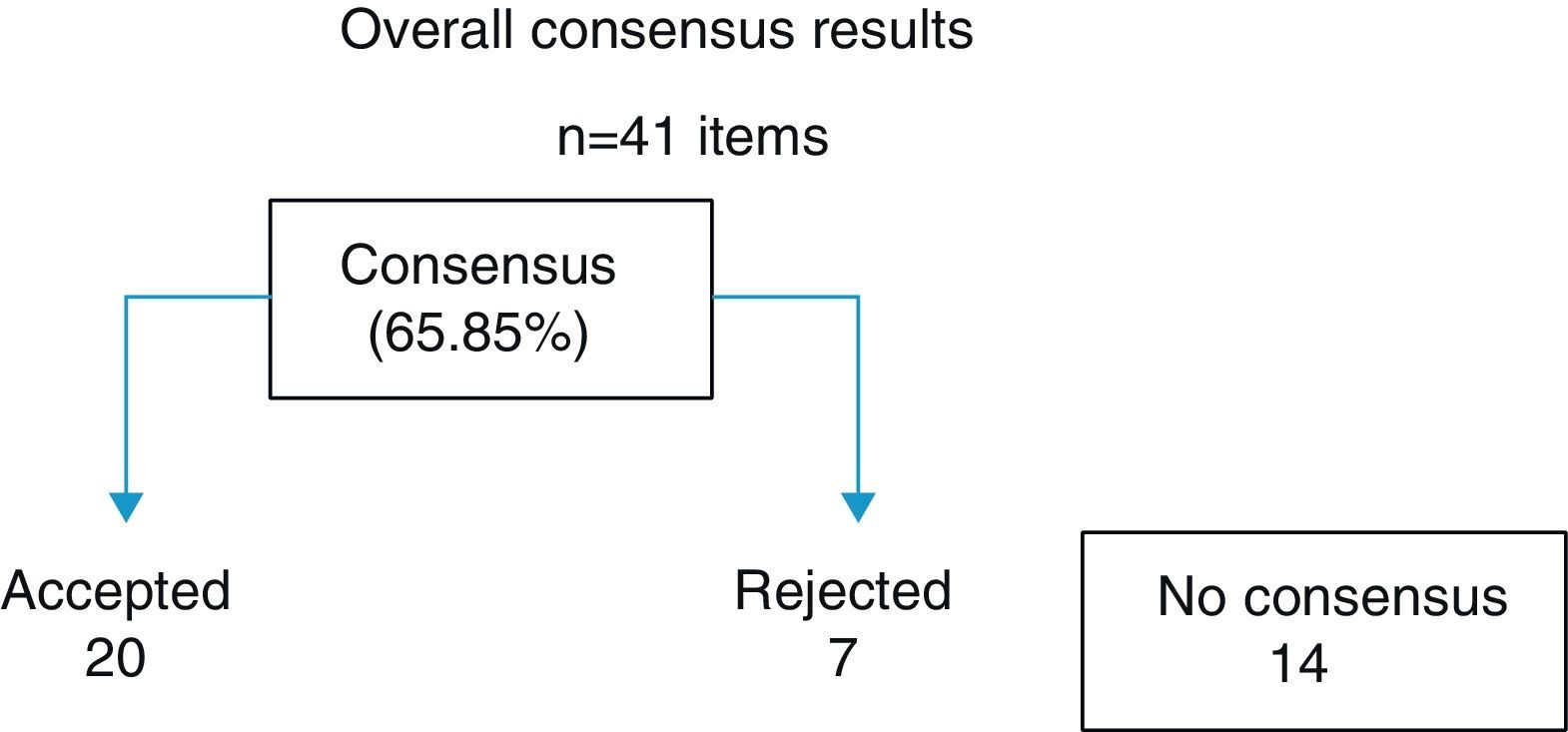

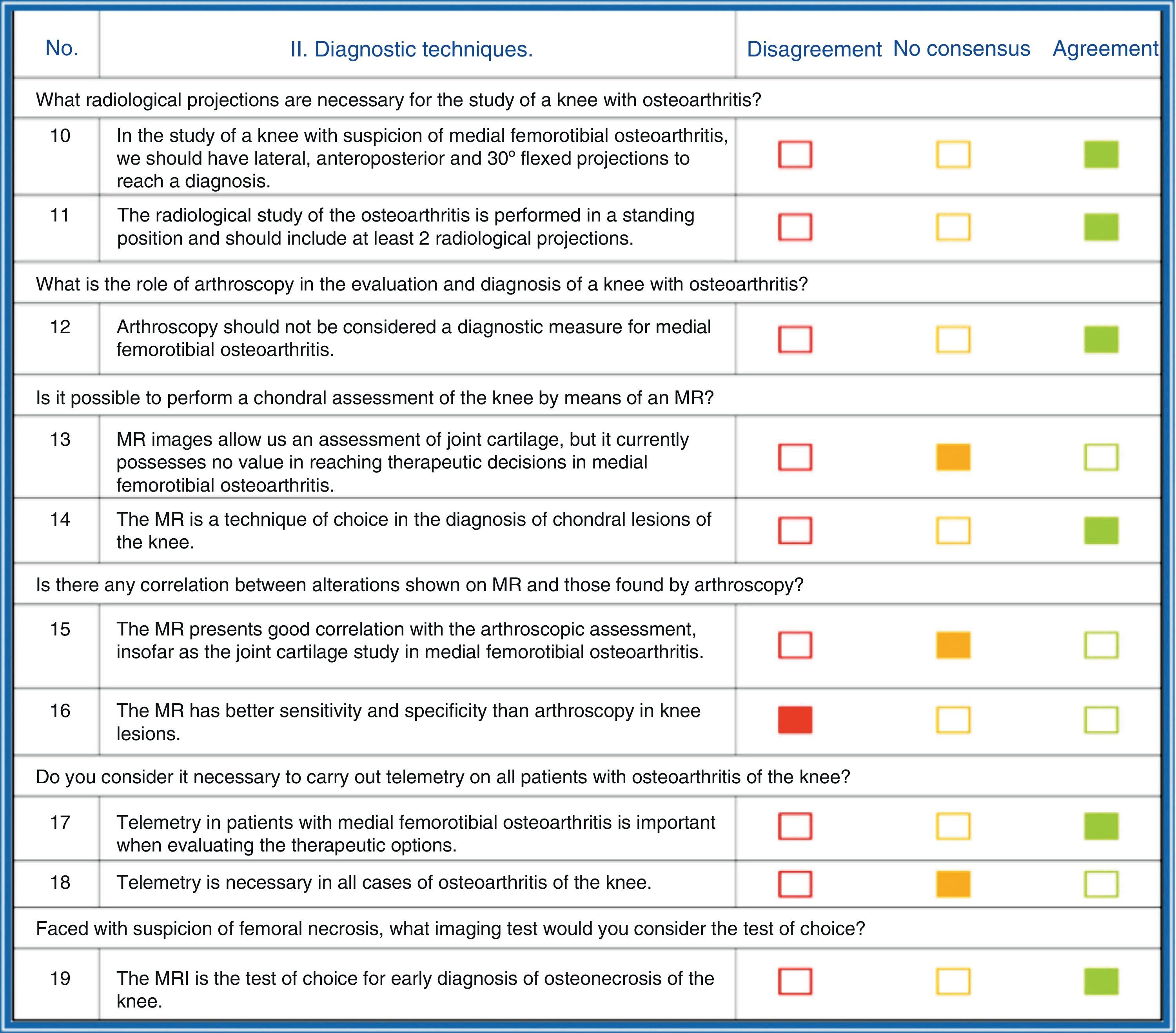

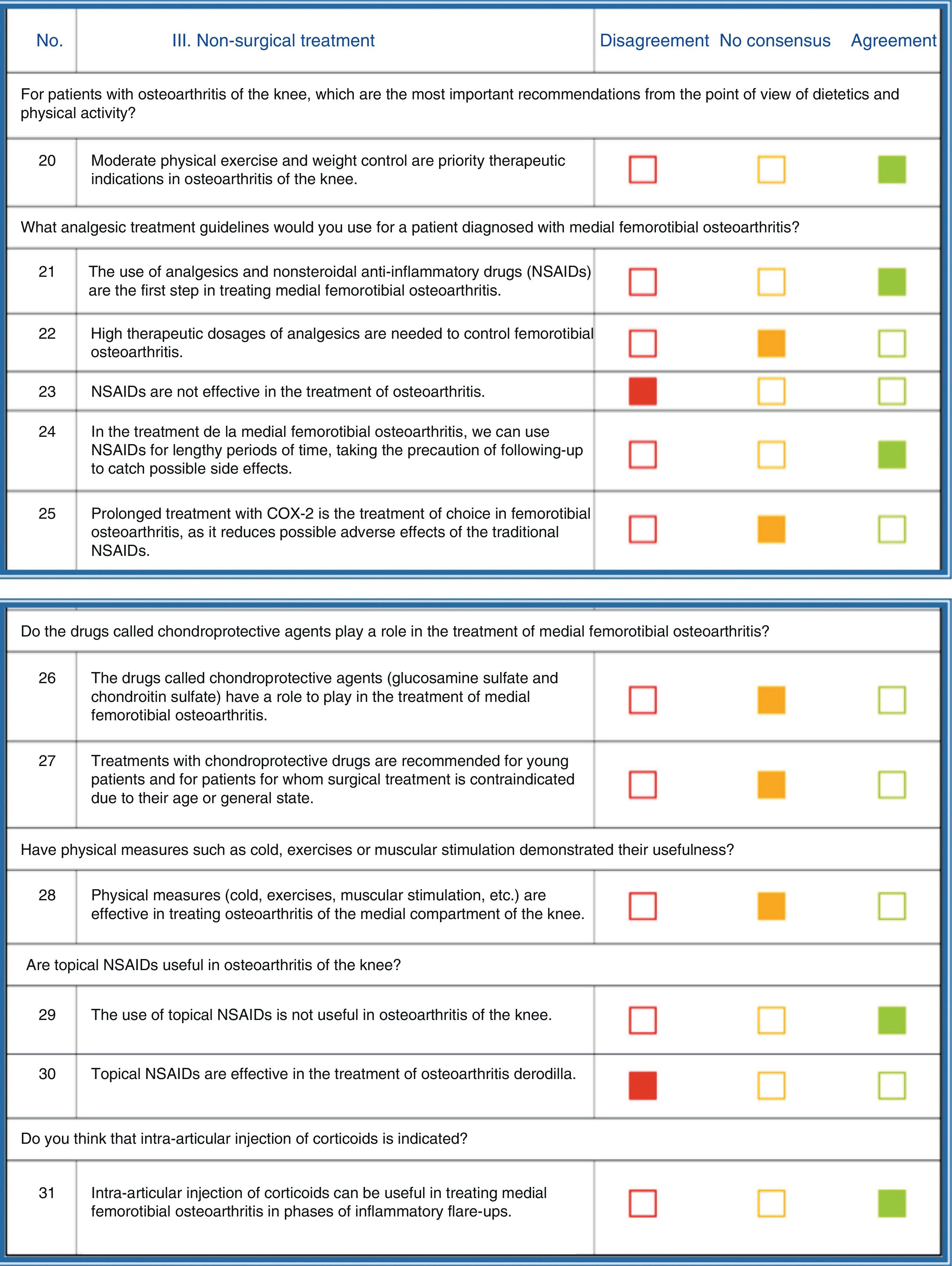

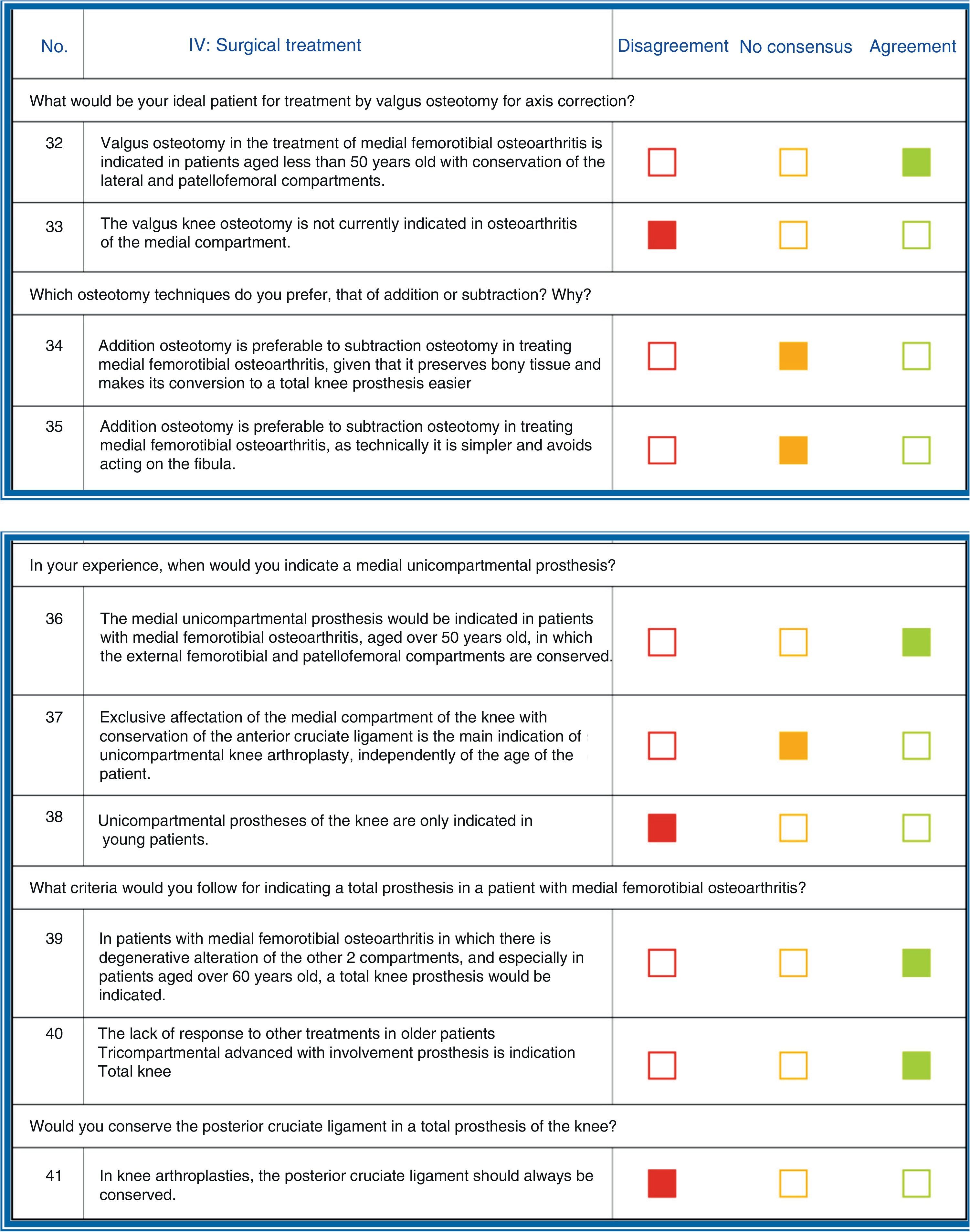

ResultsOut of the 41 questions or items carried out, a consensus was reached on 27 (65.85%). Of these, 20 of the formulations were accepted and 4 rejected. No consensus was reached on 14 of the items (Fig. 3).

The non-consensus items were included in the following sections: etiopathogenesis of osteoarthritis, value of the magnetic resonance (MR) in degenerative pathology, the usefulness of cyclooxgenase-2 (COX-2) in osteoarthritis, usefulness of chondroprotective drugs and the ideal technique for valgus osteotomy (Fig. 4).

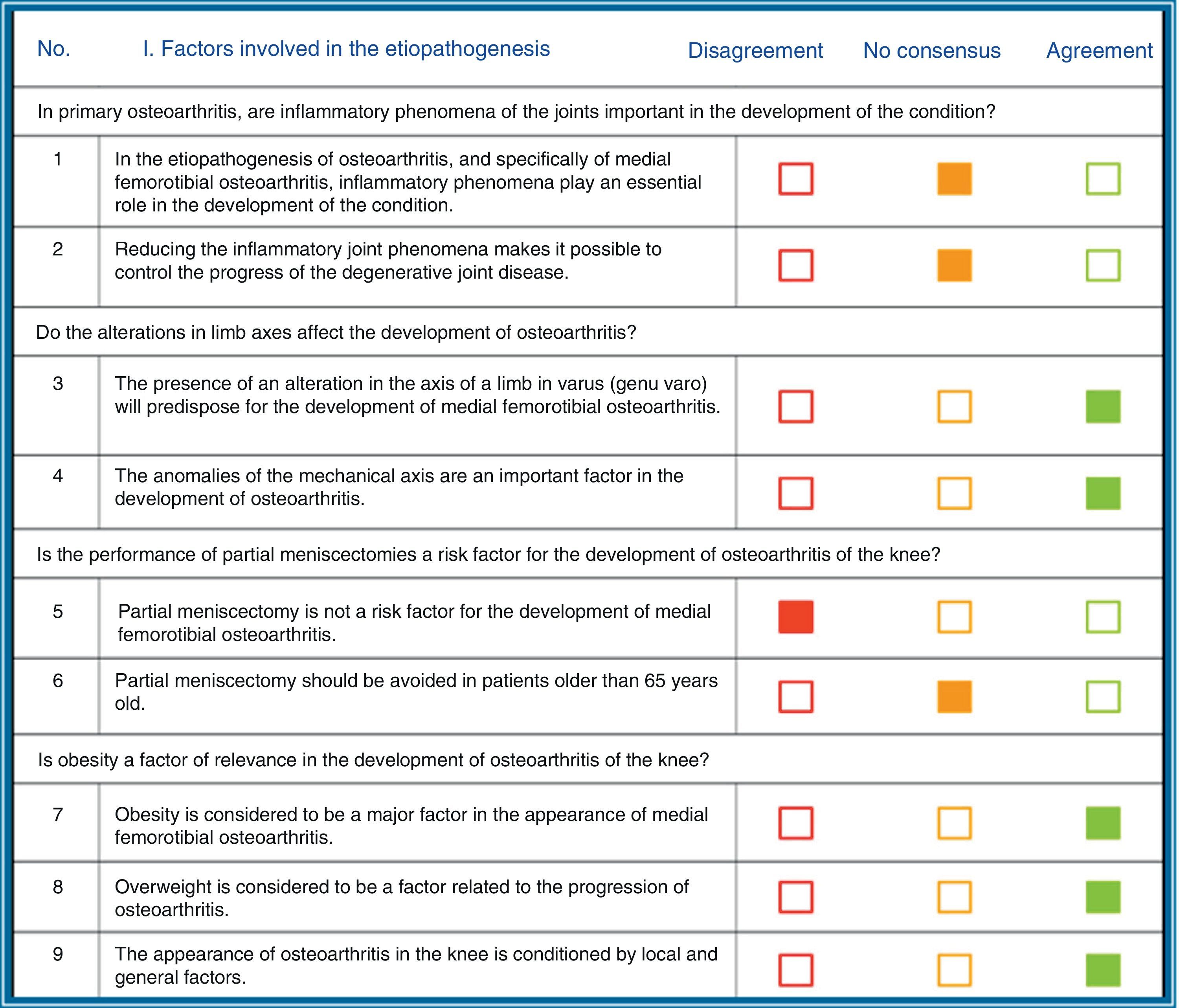

There was no consensus on the importance of the inflammatory phenomena of the disease, or on whether meniscectomy should be indicated for patients older than 65years old. The experts disagreed about whether partial meniscectomy is a risk factor for osteoarthritis of the internal knee compartment. In contrast, there was agreement on the rest of the questions about the influence of alterations in member axes as an influence in the development of osteoarthritis and also on the influence of obesity in the development of osteoarthritis.

With respect to diagnostic techniques, there was no consensus about whether, although the MR makes it possible to evaluate articular cartilage, it lacks value in reaching decisions on therapy in femorotibial osteoarthritis. Another item on which we did not achieve consensus was that the MR presents a correlation with the arthroscopic evaluation for the cartilage study, and the last item without consensus was that telemetry was needed for all osteoarthritis of the knee. There was disagreement in the item on the fact that MR has greater specificity and sensitivity than arthroscopy in knee lesions. In the rest of the items there was agreement (Fig. 5).

On non-surgical treatment, the experts disagreed on the item “NSAIDs are not effective in the treatment of osteoarthritis” and “topical NSAIDs are effective in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee”. There was no consensus on 2items: “Analgesics require high therapeutic dosages to control femorotibial osteoarthritis” and with the item “Prolonged treatment with COX-2 is the treatment of choice in femorotibial osteoarthritis as it reduces possible adverse effects of the traditional NSAIDs”. Neither was there consensus on the items on the use of chondroprotectors and physical measures in the treatment of osteoarthritis. In the rest of the items there was agreement (Fig. 6).

Insofar as the assessment of the items referring to surgical treatment, there was disagreement in 3items: “nowadays, valgus osteotomy of the knee is not indicated in osteoarthritis of the medial compartment”, “unicompartmental prostheses of the knee are only indicated in young patients” and “the posterior cruciate ligament should always be preserved in arthroplasties of the knee”. Consensus was lacking on 3items: “addition osteotomy is preferable to that of subtraction in treating medial femorotibial osteoarthritis given that it preserves the bony tissue and makes its conversion to total knee prosthesis easier”, “addition osteotomy is preferable to that of subtraction in treating medial femorotibial osteoarthritis as technically it is simpler and avoids action on the fibula” and “exclusive affectation of the medial compartment of the knee with preservation of the anterior cruciate ligament is the first indication for unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee, independently of patient age”. In the rest of the items there was agreement (Fig. 7).

DiscussionOsteoarthritis is considered a non-inflammatory arthropathy as there is no increase in leukocytes in the synovial liquid or systemic manifestations. However, we do know today that in the joint inflammatory mediators produced by chondrocytes and the synovial membrane are detected. The activation of this inflammatory process is produced by alterations in the intra-articular environment due to mechanical impairment, degradation products or pro-inflammatory cytokines. The consequence of this activation would be the expression of catabolic genes: cyclooxgenase-2 (COX-2), nitrous oxide synthase and metalloproteinase.4–7 Knowing the mechanisms of chondral degradation supports therapeutic strategies aimed at using anti-inflammatory drugs. Studies have been carried out evaluating the possible effect of the NSAIDs on joint cartilage in patients with osteoarthritis. Some of these studies have suggested a beneficial effect of the selective COX-2 inhibitors, in comparison with the traditional NSAIDs; However, epidemiological studies have not demonstrated this in relation to a possible prevention of the need for prosthetic surgery in patients treated with anti-COX-2.8,9

Etiopathogenic factorsIn the consensus elaborated, there was no agreement on the possible etiopathogenic importance of the joint inflammatory process, even though the use of NSAIDs in treating medial femorotibial osteoarthritis of the knee is accepted by the scientific community surveyed.

With respect to alterations in the mechanical axis and its relationship with the development of osteoarthritis, there was indeed agreement to accept this relationship. Although it is true that the relationship between axis alterations and osteoarthritis presence is very frequent in our daily practice, there was no scientific evidence to support this appraisal until recently. The first study published that corroborated this relationship was that by Brouwer et al.,10 which showed a statistically significant correlation between the presence of alterations in the limb axis and a later development of osteoarthritis and with the progression of the condition. More recently, Sharma et al.,11 in a multicenter observational prospective study on 2958 cases with a follow-up of 30 months, observed that the presence of varus was linked to the development of osteoarthritis and with an increase in the risk of progression of medial femorotibial osteoarthritis.

Meniscectomy, both total and partial, is a well-known risk factor for the development of osteoarthritis, given the biomechanical alterations that it involves,12 increasing the possibility of developing osteoarthritis up to 14 times. Between 30% and 70% of patients that have undergone a meniscectomy develop degenerative radiological phenomena. This fact is particularly frequent in the young patient presenting concomitant ligament instability, post-traumatic chondral lesions and axis alteration.13 In our survey, there was agreement as to the importance of meniscectomy in the development of osteoarthritis of the knee, especially in young patients. This fact has led to new strategies for treating meniscal lesions, such as sutures, transplants and the use of biological therapies.

The link between osteoarthritis of the knee and obesity is well known. The biomechanical overload that obesity produces on joint cartilage favors the appearance of lesions that lead to an extensive degenerative process.14 Gudbergsen et al.15 demonstrated that weight loss, even in patients with established osteoarthritis, is an independent, effective factor in reducing the symptoms in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. In that study, there were patients aged 50 years or older with clinical and radiological criteria of osteoarthritis of the knee, and the effect of the weight loss was assessed as an independent factor in relation to alterations of the axis and muscle force, using the KOOS and OMERACT-OARSI scales. That result supports the beneficial effect of weight loss in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. However, the mere fact of mechanical overload does not completely explain its link with the development of osteoarthritis; consequently, the involvement of endocrinological and genetic factors in its etiopathogenesis has been studied.

There are numerous studies that link altered estrogen levels in obese female patients with the development of osteoarthritis, and alteration in insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) has also been linked to the pathogenesis of the disease. These studies, however, are not conclusive but they do open new lines of research15 and new lines of work that recognize the importance of common genetic alterations to both pathologies. In the survey given to the experts, they agreed on the etiopathogenic role of obesity in the development of medial femorotibial osteoarthritis.

Diagnosis by imageDespite the development of MR imaging in chondral assessment, the simple X-ray is still the standard in evaluating the progression of osteoarthritis of the knee and in its diagnosis. To classify osteoarthritis grade, the Kellgren and Lawrence scale is still accepted, and in clinical studies the measurement of joint space narrowing is the main variable.16 Joint space narrowing is defined as the reduction of the joint space in the femorotibial articulation standing in anteroposterior (AP) projection, either in complete extension, projection at 15–30° semiflexion or the “Lyon schuss” view.17 Joint space narrowing on simple X-ray has been shown to be a variable sensitive to change; however, it is subject to possible errors in the performance technique. Consequently, it is important for the radiological studies to be carried out following projection standards to optimize the information provided by the x-rays. The utilization of fluoroscopy to position the patient has been shown to be effective, increasing the sensitivity of the studies performed. Fluoroscopic control facilitates obtaining optimized images, as the X-ray beam is positioned parallel to the medial tibial tray of the knee.18 In our study, the present agreement on the importance of the simple X-ray for assessment of medial femorotibial osteoarthritis was notable. Insofar as telemetry, its usefulness in presurgical study was accepted by the experts consulted.

With respect to MR imaging, the consensus reached included agreement on the importance of this technique in assessment of the chondral lesion. However, there was disagreement about its value in making therapeutic decisions, despite the fact that several studies have demonstrated its usefulness in studying the evolution of cartilage lesions in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee,19 with this technique being better than simple X-rays due to its sensitivity to chondral deterioration. The introduction of new chondral repair techniques has made it necessary to develop imaging techniques that evaluate the results; the MR has been the technique of choice, demonstrating its correlation with the clinical results experienced by the patients.20 In our study the experts consulted did not reach an agreement on the correlation of MR and arthroscopic findings, considering arthroscopy as the reference to evaluate cartilage.

Life habits and recommendationsAmong the recommendations given to the patient affected by osteoarthritis of the knee, it is necessary to insist on the importance of the information that can be given patients as part of their non-surgical treatment.21 There are meta-analyses and clinical trials that have emphasized that using the educational techniques yields benefits in the reduction of pain and in the decrease in visits to primary care physicians, with the consequent economic savings.22,23 Examples are individualized education programs, regular telephone calls and support groups.24 These procedures make patients learn to live in accordance with their functional condition, avoiding unnecessary efforts or activities and carrying out appropriate practices. Rest is recommended when episodes of acute pain occur, it being helpful to alternate rest with progressive activity while avoiding (as much as possible) prolonged immobilization that would favor muscle atrophy and progression of the disease. Night-time rest of at least 8h seems to be recommendable.25 Another measure about which there was consensus among the specialists was the application of a diet aimed at weight control, given that excess weight in a major risk factor for the development and progression of osteoarthritis in load-bearing joints.26 There is evidence that weight loss is linked to a lower degree of development of symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee in females.27 However, what is not clear is whether weight loss slows the advance of the disease or merely relieves the symptoms of patients affected by prior osteoarthritis. Just as with patients that are candidates for reconstructive knee surgery, patients with medial osteoarthritis of the knee should be encouraged to participate in a rational weight reduction program that includes aerobic exercise and diet.28 The use of specific diets does not appear to be recommendable for these patients.

Another aspect on which there was consensus among the specialists consulted was that moderate physical exercise makes it possible for these patients to perform the activities in daily life for which they sometimes encounter functional limitations.29 Physical therapy improves muscle strength, joint stability and mobility in the arthritic patient. Controlled exercise improves joint mobility and periarticular muscle strength; its objectives are to prevent lesions and incapacity, as well as reduce pain and rigidity while maintaining functionality as long as possible. Aerobic exercise has been demonstrated to be useful and effective in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, especially walking, bicycle riding and water, recreational or gymnastic exercises, all for 30–60min a day.30 Strengthening the quadriceps by isometric or isokinetic exercises is linked to an improvement in the strength of that muscle, to better joint function and to reduction in knee pain. However, performing exercises requires an effort by the patient and it is evident that the degree of adherence to the exercise program is linked to functional and clinical improvement.29 From the therapeutic point of view, only high-impact exercises should be avoided.31 The use of devices that permit the lessening of the load on the affected limb (cane in the contralateral hand) reduces the load on the joint affected and are linked to improved function and reduced pain.32

Drug treatment and physical therapyAnalgesic treatment should be understood as a complement to the diet and health measures mentioned earlier. There was consensus on the fact that treatment based on analgesics and NSAIDs is the first therapeutic option in osteoarthritis of the knee. The oral drug of choice is paracetamol, because of its efficacy, its safety profile and the low economic cost involved. If it is effective in controlling pain, it is the long-term medication of choice.30 The NSAIDs are a group of heterogeneous drugs used generally as the first step in treatment of medial femorotibial osteoarthritis. They are substances with analgesic, anti-inflammatory and fever-reducing properties, whose mechanism of action is the “inhibition of cyclooxgenase”, an enzyme that participates in the metabolism of prostaglandins, so the effect that they achieve is the reduction in the liberation of inflammatory mediators. The NSAIDs are the therapeutic agents of choice for patients not responding to paracetamol and, fundamentally, if the inflammatory component is significant.30,33,34

Paracetamol is an agent effective a high dosages (2–4g/day), although the daily dosage of 4g should not be exceeded as it is hepatotoxic.35–38 It is a good idea to control prothrombin time in subjects under treatment with anticoagulants that are going to receive high dosages of paracetamol.32 However, there are few studies that back the efficacy of paracetamol as a single treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee, given that it is used as a complementary treatment in the majority of cases.30 What has been demonstrated is that the gastrointestinal safety profile of paracetamol is better than that of NSAIDs, which are also used in treating this disease.39 The use of opiates (tramadol, codeine, buprenorphine, transdermal fentanyl and oxycodone) for patients suffering from osteoarthritis of the knee with poor analgesic control could be useful in the short term in acute flare-ups.40,41 There are studies and clinical trials that have shown that tramadol, as it inhibits serotonin and noradrenalin recapture, would make it possible to reduce the dosage of the NSAID; tramadol could consequently be useful as an adjunct treatment in patients whose symptoms are not controlled correctly with anti-inflammatory therapy. Opiates reduce the intensity of the pain, without risk of intestinal hemorrhage or renal problems, but they are of little benefit in the improvement of joint function.42 In addition, the adverse effects opiates trigger can represent a problem, especially in long-term treatments.43 The American College of Rheumatology (ACR)44 suggests using opiates as the last option in treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee.

Different studies have compared paracetamol and NSAIDs directly, with the latter showing greater efficacy; however, the NSAIDs also had a greater number of adverse episodes, especially gastrointestinal. The majority to the experts surveyed considered the NSAIDs as an effective therapeutic option in treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Individualized treatment with NSAID requires an analysis of comorbidities and associated therapies in the patients, as well as of the possible collateral effects and cost of the treatment. It is estimated that, in subjects aged over 65 years, up to 20–30% of hospitalizations and deaths are due to peptic ulcer disease attributable to the consumption of NSAIDs, and that the risk depends on the dosage in this population.45,46 Likewise, patients with underlying renal disease are at risk of developing kidney failure when they use NSAIDs to control osteoarthritis of the knee.32 The use of non-selective NSAIDs together with gastro-protective drugs is a common practice. It has been shown endoscopically that misoprostol significantly reduces the risk of ulcers, although it is an agent that presents side effects (such as diarrhea and flatulence).47 The anti-H2 agents at common dosages reduce the risk of duodenal ulcers but not that of gastric ulcers; consequently, double the normal dosage should be used or proton pump inhibitors should be utilized to reduce the risk of duodenal and gastric ulcers.48 In low-risk patients the use of gastroprotective agents is not indicated.30 Less frequent adverse effects are reactions of hypersensitivity and hematological reactions (agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia, etc.). The majority of the experts surveyed agreed with the fact that these drugs were acceptable for long-term use, as long as correct screening was performed for possible side effects. In this respect we have already mentioned the importance of appropriate control of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients that use NSAIDs chronically, as well as the recommendation not to use NSAIDs in subjects with creatinine clearing above 2ml/min/1.73m2 and high arterial blood pressure values. The NSAID dosage should be the lowest that shows therapeutic efficacy, although there is no consensus as to the appropriate dosage to treat femorotibial osteoarthritis. The initial dosage should be low and increased if it is not effective in relieving the symptoms. The use of this medication should be accompanied by non-drug therapeutic measures, such as moderate exercise, weight control, bed rest in the acute phases and the use of off-load devices (among others), as such measures will allow us to reduce the dosage of the NSAID or even substitute paracetamol for it.29

The combination of various NSAIDs should be avoided as much as possible, except for aspirin at an anti-aggregant dosage, given that this combination of various drugs does not increase anti-inflammatory strength while it does increase adverse effects.32 The choice of a specific NSAID is totally empirical and is largely determined by the frequency of administration and the price. Administration of NSAIDs should preferably be oral, leaving the rectal and parenteral for certain exceptions.

There was no agreement on whether prolonged treatment with COX-2 if the therapy of choice in osteoarthritis of the knee, because although these drugs do present fewer adverse effects than traditional anti-inflammatories, we have pointed out the presence of risk factors for developing gastrointestinal side effects (>65years old, history of ulcus, use of corticoids or oral anticoagulants, etc.) that have to be taken into consideration.49 Los COX-2, including second-generation ones, have shown efficacy similar to non-selective NSAIDs in relieving pain50,51 with a reduction of close to 50% in gastrointestinal complications.52,53 They are well tolerated at the dosages recommended, with scarcely any incidence of collateral gastrointestinal effects as compared to non-selective NSAIDs.54,55 None of these drugs has shown a clinical effect on plaque aggregation or hemorrhage time, which is important in managing patients with osteoarthritis of the knee that also take anticoagulants.34 Nevertheless, the renal and cardiovascular side effects are similar to those that non-selective NSAIDs trigger, so they should be used with caution in patients that have high blood pressure, moderate or severe renal failure and in cases of congestive heart failure.56,57 Nonetheless, some meta-analyses suggest that the COX-2 can be harmful in patients at high gastric risk,58 and clinical guidelines usually advise against their use in this type of patients.

We did not find consensus on the usefulness of the symptomatic slow-acting drugs for osteoarthritis (SYSADOA) in degenerative arthropathy. These slow action drugs have demonstrated their capacity to reduce pain in osteoarthritis of the knee with efficacy equivalent to NSAIDs and with fewer adverse reactions. However, as their name indicates, they are slow-acting and their effect does not come into force until after 2 or 3weeks from commencing treatment; consequently, they are not effective as “rescue” analgesics. Their activity lasts up to 2–6months after ceasing administration, due to the increase in proteoglycan synthesis in joint cartilage, and they modify the progression of the arthritis.25,59 Glucosamine sulfate stimulates the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans (GAG) and inhibits the synthesis of colagenase 1, aggrecanase and phospholipase A2. With the pain visual analog scale (VAS) glucosamine sulfate has been shown to relieve the symptoms evaluated and, above all, to present fewer adverse effects than the NSAIDs.60

Condroitin sulfate is another SYSADOA that reduces synthesis of MMP (colagenase, elastase) and of nitric oxide and increases that of hyaluronic acid and GAGs.61 It is effective in controlling pain; some authors have considered it similar to dyclofenace, which provides a functional improvement in osteoarthritis of the knee, shows an appropriate safety profile and allows decreasing the dosage of analgesics and NSAIDs. However, as has occurred in our survey, the studies published on its efficacy are controversial62 and require a greater number of studies including or excluding this drug in the therapeutic arsenal for osteoarthritis.

After the publication of “The Arthritis Cure” in 1997,63 glucosamine has been the object of many studies and has been shown to be a safe, effective product in different meta-analyses.64–67 However, the conclusions have not been easy to reach due to defects in the methodology used in some cases and to commercial interests. In 2006, the US National Institute of Health (NIH) funded the glucosamine/chondroitin arthritis intervention (GAIT) study,66 on 1583 patients affected by osteoarthritis, comparing glucosamine, chondroitin and the combination of the 2 drugs with celecoxib and a placebo group. The glucosamine/chondroitin sulfate combination showed a response that was 6.5% greater than the placebo group, but without statistical significance. The excellent safety demonstrated in all the clinical research carried out with both SYSADOAs (clinical trials and meta-analyses) is of special interest in prolonged treatment of the disease, particularly when it is a pathology that affects the elderly and the poly-medicated. In the opinion of specialists in orthopedic surgery and traumatology, SYSADOAs are highly useful in patients on waiting-lists for operations, without provoking problems that can delay the surgery. It has been suggested that chondroitin sulfate would be capable of reducing the need for implanting prostheses in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee,68 with the consequent pharmaco-economic, social and health services benefits that this would suppose.

The use of SYSADOAs is not limited to young patients or to those in whom surgical treatment is not indicated. With respect to chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate, there is no evidence that adjusting the dosage is required for elderly patients. In addition, the only aspect to bear in mind with these drugs is to avoid the use of glucosamine sulfate in subjects with inherited intolerance to fructose and in patients affected with phenylketonuria. Nor does diacerein require adjustments in dosage for the elderly, although it can present symptoms at the intestinal, urinary and cutaneous levels when treatment is initiated.59 Despite the results obtained, the traumatologist should know that these drugs are a good option given their scant incidence of adverse effects, and the benefits that these treatments can provide should be clearly explained to the patient.

We did not find consensus and unanimity either with respect to the benefits obtained with physical measures. Cold is useful in the acute phase of pain, applying it by means of frozen bags or gelatin for 10–15min, avoiding direct application on the skin.22 As for heat, there is controversy about the benefits obtained, although improvement in the initial control of the rigidity that is part of arthritic joints is attributed to heat. In the subacute and chronic phases, it seems that infrared heat combined with analgesic currents can have beneficial effects, according to some authors.63

There was consensus in the survey performed with respect to the fact that topical NSAIDs are ineffective in treating osteoarthritis of the medial compartment. Based on the scientific literature, we can state that some of the topical drugs used at present can be useful in cases in which paracetamol is insufficient, and cases prior to or concomitant with the administration of an NSAID.64 These drugs usually liberate substance P in the peripheral nerve terminations that participate in transmitting pain and in the inflammation that a moderate analgesic would produce in the area applied to inhibit these nerve terminations (although we cannot rule out a placebo effect). Nevertheless, they can trigger a slight skin irritation in the area of application. However, we should emphasize that there was total agreement in that therapy with topical NSAIDs did not make it possible to treat osteoarthritis of the knee. The post-application effect is subjective and can stem from the benefit of the massage used in their application, which would encourage venous and lymph drainage.

Our experts surveyed agreed that the use of intra-articular corticoids, in acute phases, could provide symptomatic benefits to the patient. Faced with the presence of an articular hemorrhage, drainage and later study of the joint fluid are recommended, with short- and medium-term infiltration of corticoids to reduce the pain.32 It should be remembered that the beneficial effect of these drugs is in the short- and medium-term,65 and that this treatment is usually used as an adjunct to systemic therapy. However, infiltrations of corticoids should not be performed more than 3 times a year because of the cartilage damage that can be triggered, especially in load-bearing joints such as the knee.69 Likewise, it should be remembered that, as in all invasive techniques, this should be carried out in aseptic conditions.

Surgical treatmentWith respect to surgical treatment, and specifically related to valgus osteotomy, there was consensus in that the ideal patient would be an individual younger than 50years old with preservation of the lateral and patellofemoral compartments. Effectively, the high tibial osteotomy is indicated in young, active patients with osteoarthritis located in the internal compartment of the knee and with genu varo70 that, despite the development of prosthetic surgery, is still a valid option for treating medial femorotibial osteoarthritis, as both the consensus in our study and the literature reflect.71

Insofar as surgical technique, whether addition or subtraction, no consensus was reached. In fact, a meta-analysis72 did not find any significant differences between the 2 types of osteotomy. Nonetheless, the alterations that the osteotomies produce in the tibial slope make it necessary to know the state of the cruciate ligaments to decide upon one technique or the other. Subtraction osteotomy reduces the fall of the tibial stem, while that of addition increases it.73

We found consensus on the indication of the unicompartmental prosthesis unicompartmental: for patients aged 50 years or older with limited osteoarthritis in the medial compartment, and they should not be indicated exclusively for young patients. This is in accordance with the literature.74 Based on the studies published, we should also consider as contraindications (at least relative contraindications) the existence of overweight or ligament alterations, or patients used to significant physical activity.75 However, there was no agreement with the fact that exclusive affectation of the medial internal compartment of the knee with conservation of the anterior ligament is the main indication of this type of arthroplasty, when this is indeed considered to be so in the current literature.76

Insofar as the total knee prosthesis (TKP), there was consensus on the 3 questions, in the indications for its implantation, in agreement with accepted clinical guidelines, and in that it was not always necessary to conserve the posterior cruciate ligament. In a systematic review, it has been shown that sacrificing the posterior cruciate ligament could increase the range of mobility.77

The SECOT consensus on medial femorotibial osteoarthritis of the knee being finalized, we wish to emphasize that axis alterations, obesity and meniscectomy are factors involved in its etiopathogenesis. Simple X-rays still continue to be the fundamental diagnostic method. Systemic NSAIDs, diet and health measures and intra-articular infiltrations with corticoids are indicated in treatment of the condition. It would be necessary to establish a protocol of non-surgical action with symptomatic slow-acting drugs for osteoarthritis (SYSADOA) that have few side effects. Valgus osteotomy, unicompartmental prosthesis and total prosthesis are surgical possibilities in its treatment that have some clear indications for each type of patient.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence V.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments on human beings or on animals were performed for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Please cite this article as: Moreno A, Silvestre A, Carpintero P. Consenso SECOT artrosis femorotibial medial. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2013;57:417–428.