Closing wedge high tibial osteotomy (CW-HTO) is a surgical option for active patients with medial knee pain and mild–moderate osteoarthritis with varus limb deformity. Despite its good reported results, this technique has been losing popularity. The aim of this study was to analyse the survival rate, clinical functional outcomes and radiological results of CW-HTO.

MethodsIt is a retrospective case series study. Seventy patients with primary knee osteoarthritis, operated on between 2010 and 2020 in a single Spanish tertiary hospital using the CW-HTO technique and with a minimum follow-up of 2 years were analysed.

ResultsSurvival rate was 87.6% and 75.5% after a follow-up of 5 and 10 years respectively. Functional outcomes were good-to-excellent (KSS 77.7/100 and OKS 35.6/48) and good pain control (VAS 3.9/10) and high satisfaction (7.2/10) were achieved. Limb varus malalignment was significantly corrected (mean postoperative HKA angle 177.6° and MPTA 90.7°). However, 30% of patients presented hypocorrection, which was associated with inferior survival, functionality and satisfaction.

ConclusionCW-HTO technique can be useful for patients with knee osteoarthritis and varus limb. It allows to correct varus malalignment while achieving good-to-excellent functional outcomes, good pain control, high patient satisfaction and acceptable medium-long term survival rate. However, it is associated with a non-negligible risk of hypocorrection or medial hinge disruption.

La osteotomía tibial alta de sustracción lateral (OTA-SL) es una opción quirúrgica para pacientes activos con dolor en el compartimento medial de la rodilla y artrosis leve-moderada, acompañada de deformidad en varo de la extremidad. A pesar de los buenos resultados reportados, esta técnica ha ido perdiendo popularidad. El objetivo del estudio fue analizar la tasa de supervivencia, resultados clínicos funcionales y resultados radiológicos de la OTA-SL.

MétodosEste estudio es una serie de casos retrospectiva. Se analizaron 70 pacientes con artrosis primaria de rodilla, intervenidos entre 2010 y 2020 en un único hospital español de tercer nivel mediante la técnica OTA-SL y con un seguimiento mínimo de dos años.

ResultadosLa tasa de supervivencia fue de 87,6% a los cinco años y de 75,5% a los 10 años de seguimiento. Los resultados funcionales fueron buenos-excelentes (KSS 77,7/100 y OKS 35,6/48) y se obtuvo un buen control del dolor (EVA 3,9/10) y elevada satisfacción (7,2/10). Se logró corregir de forma significativa la malalineación vara de la extremidad (ángulo HKA posoperatorio medio 177,6° y MPTA 90,7°). Sin embargo, 30% de los pacientes presentó hipocorrección, asociándose a inferior supervivencia, funcionalidad y satisfacción.

ConclusiónLa técnica OTA-SL puede ser una opción útil para pacientes con artrosis de rodilla y extremidad en varo. Permite corregir la malalineación vara de la extremidad, ofreciendo buenos-excelentes resultados funcionales, buen control del dolor, elevada satisfacción y una aceptable tasa de supervivencia a medio-largo plazo. Sin embargo, se asocia a un riesgo no despreciable de hipocorrección o disrupción de la bisagra medial.

Knee valgus osteotomy is a joint preservation technique based on moving the mechanical axis of the limb laterally to reduce the percentage of load on the medial compartment of this joint.1 The classic criterion for performing this technique is the young and active patient with medial joint pain, mild–moderate osteoarthritis isolated to the medial compartment and varus axis of the limb.2,3 Furthermore, in recent years, the indications for performing this procedure concomitantly with meniscal, chondral or ligamentous surgery have increased.4,5

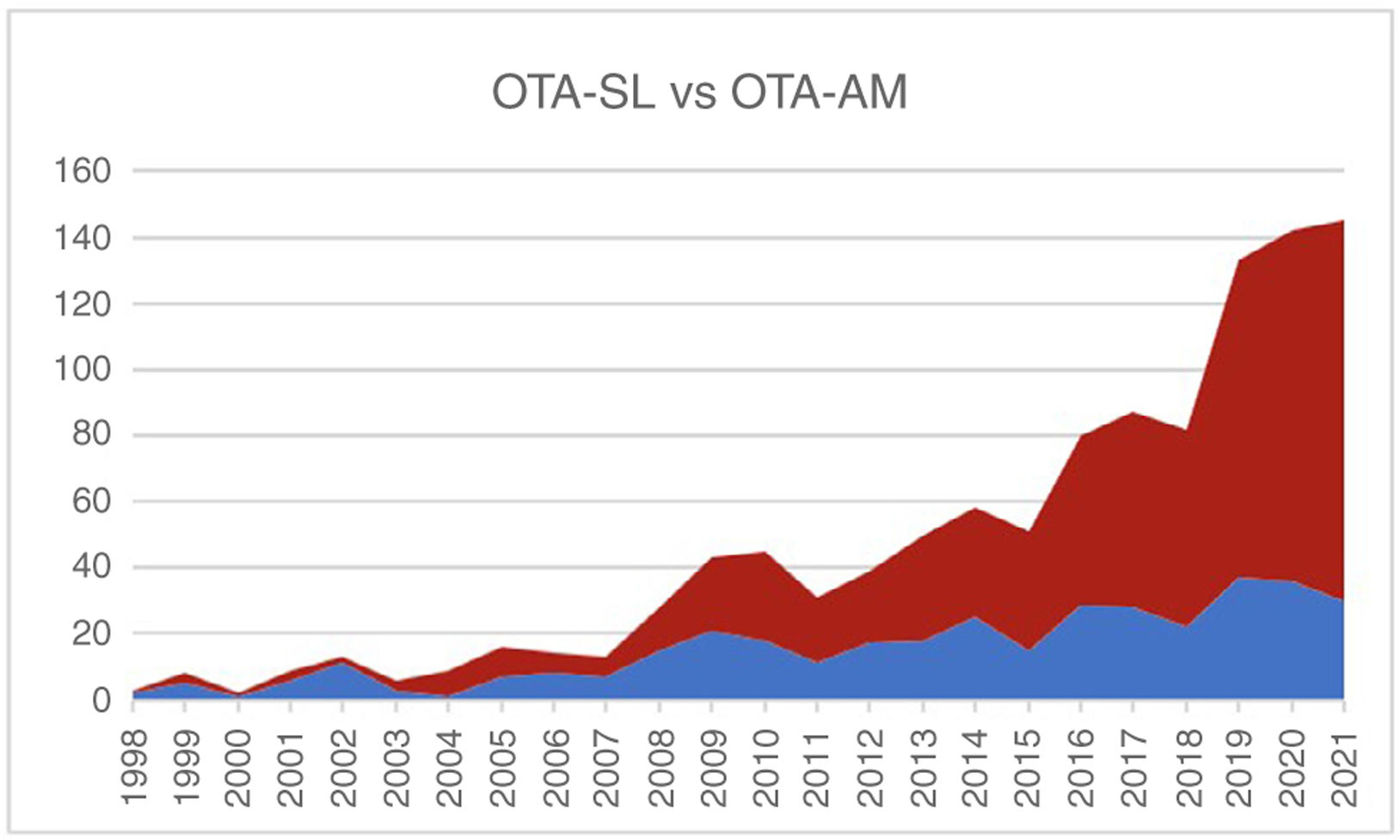

There are various surgical techniques to perform this axis correction. When the variation is due to a tibial metaphyseal varus, the two most used techniques are the medial opening high tibial osteotomy (MO-HTO) and the closing wedge high tibial osteotomy (CW-HTO). Although these two present particularities and nuances, most prospective comparative studies have not found relevant differences in their clinical and radiological results or conversion rate to arthroplasty.6–9 However, the medial opening technique has been gaining popularity compared to the closing wedge technique (Fig. 1).

The objective of our study was to analyse the survival rate, functional clinical results and radiological results of knee valgus osteotomy using the CW-HTO technique.

MethodsStudy designThis study is a retrospective case series. As this was a retrospective observational study, exemption from informed consent was obtained from the Ethics Committee of our centre. The inclusion criteria were: (a) adult patients, (b) primary knee osteoarthritis, (c) operated on in a single Spanish tertiary hospital, (d) CW-HTO technique, (e) operated between 2010 and 2020, (f) minimum follow-up of two years, (g) have strictly correct preoperative and postoperative radiographs (anteroposterior and knee profile and lower extremity telemetry) and (h) have functional questionnaires at the end of follow-up. The exclusion criteria: (a) skeletally immature patients, (b) secondary osteoarthritis, (c) inflammatory arthritis or (d) deformity secondary to infection, malignancy or fracture.

Study variables- (1)

Survival rate: measured based on the requirement for conversion to total knee prosthesis (TKA) during follow-up.

- (2)

Functional clinical results: they were determined at the end of follow-up using the questionnaires Knee Society Score – Function (KSS) (0–100 points), Oxford Knee Score (OKS) (0–48 points), visual analogy pain scale (VAS) (0–10 points) and satisfaction scale (0–10 points).

- (3)

Radiological results: the last preoperative radiographs and the last radiographs available at the end of follow-up were analysed. The Hip-Knee-Ankle (HKA) angle, medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA), tibial slope, patellar height (Caton-Deschamps index) and the degree of femorotibial osteoarthritis (Ahlback classification) were measured.

Other variables were also recorded: (a) preoperative demographic (gender and age at the time of intervention), (b) intraoperative (duration of surgery and intraoperative complications) and (c) postoperative (complications and follow-up time).

Information regarding the survival rate and radiological data were obtained through the computerised medical record. All radiological measurements were performed only once by a resident doctor in orthopaedic surgery (member of the research team) using the RaimViewer software (UDIAT Diagnosis Centre, Sabadell, Spain). To obtain functional clinical data, a member of the research team conducted a telephone interview with all patients and it was confirmed that they would not have required conversion to TKA in another centre.

Surgical techniquePatients with knee osteoarthritis who are candidates for tibial osteotomy are studied radiologically before indicating surgery using anteroposterior projections and knee profile and telemetry of the lower extremities. The criteria to indicate the CW-HTO technique in our centre are: pain in the medial interline, osteoarthritis of the medial compartment, absence of significant osteoarthritis in the lateral compartment, varus axis of the limb (5–15°), tibial metaphyseal varus (MPTA <87°), absence of patella alta and preserved joint balance (>90°). Although they are not absolute criteria, it is preferred to indicate the procedure in patients aged <65 years, active, body mass index (BMI) <35kg/m2 and non-smokers. Interventions are planned preoperatively using computer software. The final alignment goal (magnitude of correction) was established between the neutral mechanical axis and the Fujisawa point.10 This objective is individualised depending on the indication, severity of the disease and axis of the contralateral limb.3 All osteotomies were performed by two surgeons from the knee unit who were experts in this technique.

The clincian places the patient in a supine position, dropping the leg over the lower edge of the surgical table with 90° knee flexion. The proximal ischaemia cuff is placed on the thigh and the knee is fixed with a clamp. It is verified that the positioning of the fluoroscopy allows for a strict anteroposterior projection and knee profile. A longitudinal incision of about 5cm is made cantered on Gerdy's tubercle. The iliotibial band is partially disinserted. After identifying and protecting the common peroneal nerve, the proximal tibiofibular joint is disarticulated using a blunt chisel. The location where the osteotomy cuts will be made is identified and marked on the anterolateral tibial surface, proximal to the anterior tibial tuberosity, according to the previous planning. Two bone cuts are made in the tibia using an oscillating saw and under scopic control. A bone wedge is obtained in the shape of an isosceles triangle, maintaining a 1cm medial hinge. The osteotomy is carefully closed under clinical and radiological control and is then synthesised using a staple. At the end, an X-ray is performed to check the correct closure and fixation of the osteotomy, the alignment of the limb, the posterior tibial slope and the patellar height. The surgical wound is washed and sutured in layers.

Partial weight bearing and knee flexion–extension are allowed from the first postoperative day. The full load is introduced progressively from the third week. They are visited in the first, second and third week to carry out a clinical control and ensure the correct evolution of the surgical wound. Subsequently, they are visited at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months to perform a clinical and radiological control (Fig. 2).

Radiological and intraoperative images of a patient undergoing two-stage bilateral CW-HTO. (A) Telemetry and HKA measurement pre (A.1) and postoperative (A.2). (B) Intraoperative fluoroscopy after removing the subtraction wedge (B.1) and after placing the fixation clip (B.2). (C) Intraoperative clinical images showing the execution of the bone cuts (C.1) and the verification of the thickness of the subtraction wedge once it has been removed (C.2).

Descriptive statistics were used to present the characteristics of the cohort. Categorical variables were described through their absolute value and percentages. The continua were presented with their mean, standard deviation and range. The comparative analysis of parametric quantitative variables was performed with the t-test, considering statistical significance with a p value <.05. The osteotomy survival study was analysed using the Kaplan–Meier curve. The SPSS Statistics 20.0 programme (IBM-SPSS, New York, USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis.

ResultsA total of 70 patients (60% men and 40% women) met the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were analysed for the study. The mean age at the time of the intervention was 58.7±7.1 years (range 36–73). The mean follow-up time was 8.0±2.8 years (range 2–12).

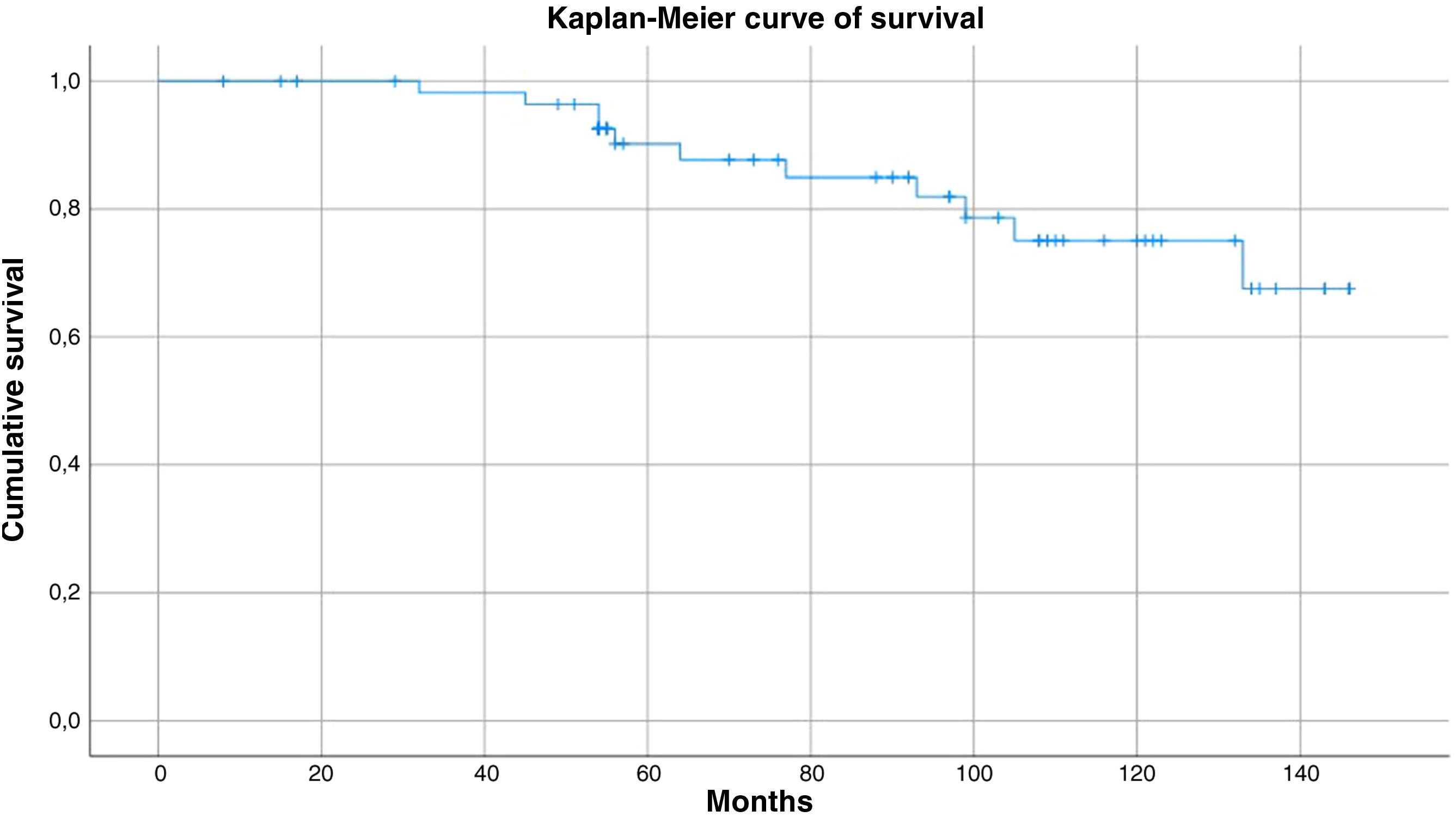

The osteotomy survival rate at three, five, eight and 10 years was 96.4%, 87.6%, 75.5% and 75.5%, respectively, with a survival at the end of follow-up of 72.9%. Fig. 3 shows the Kaplan–Meier survival curve. At the end of follow-up, 19 patients required conversion to TKA (or were on the waiting list). In these subjects, the mean time between osteotomy and conversion to arthroplasty was 4.3 years. Age <55 years and medial hinge disruption have not shown an association with the survival rate (p=.82 and p=.72, respectively).

The functional results at the end of follow-up were: KSS 77.7±22.5 and OKS 35.6±9.4. The pain perceived by patients according to the VAS scale went from 8.1±1.8 before surgery to 3.9±3.1 at the end of follow-up. The overall satisfaction of the patients regarding the osteotomy was 7.2±2.8 out of 10. However, patients who did not require conversion to a prosthesis presented a satisfaction of 7.9±2.1.

The radiological results are summarised in Table 1. The mean grade of preoperative femorotibial osteoarthritis according to the Ahlback classification was 1.9±.8 (G-I: 37.1, G-II: 40, G-III: 17.1 and G-IV: 5.8%). When comparing the radiological and clinical results between patients who had a milder stage of osteoarthritis and those who had a more advanced stage, no significant differences were found (Table 2). Likewise, patients who achieved a postoperative HKA angle ≥177° (49/70, 70%) and those who presented undercorrection with HKA <177° (21/70, 30%) were also compared. The analysis of the association between the correction of malalignment and various relevant variables (survival, functionality, pain and satisfaction) is summarised in Table 3.

Preoperative and postoperative radiological results and the differences between both in patients operated on using the CW-HTO technique.

| Variable | Preoperative | Postoperative | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| HKA angle | 170.1±3.5 | 177.6±3.0 | .01* |

| MPTA angle | 86±2.9 | 90.7±3.9 | .04* |

| Tibial slope | 9.3±3.3 | 7.5±3.5 | .01* |

| Patellar heighta | .95±.2 | .98±.2 | .33 |

CW-HTO: closing wedge high tibial osteotomy; HKA: Hip-Knee-Ankle; MPTA: medial proximal tibial angle.

Analysis of the association between the degree of preoperative osteoarthritis (Albhack ≤II vs. Albhack >II) and various relevant variables.

| Variable | Albhack ≤II(n=54/70, 77.1%) | Albhack >II(n=16/70, 22.9%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative HKA angle | 171.0±3.2 | 170.0±4.0 | .38 |

| Postoperative HKA angle | 179.5±2.9 | 177.2±3.2 | .72 |

| Tibial slope difference | −3.1±2.8 | −3.6±2.5 | .60 |

| Patellar height differencea | .08±.68 | .05±.37 | .11 |

| Suvivalb | 75.5% | 91.7% | .22 |

| Functionality (KSS) | 79.44±21.54 | 82.92±19.36 | .62 |

| Functionality (OKS) | 36.36±9.01 | 37.42±9.25 | .72 |

| Improvement in painc | 4.56±3.14 | 4.42±2.50 | .89 |

| Overall satisfaction | 7.51±2.46 | 8.42±1.31 | .28 |

HKA: Hip-Knee-Ankle; KSS: Knee Society Score; OKS: Oxford Knee Score.

Analysis of the association between the degree of correction of varus malalignment of the limb using the CW-HTO technique (HKA ≥177° vs. HKA <177°) and various relevant variables.

| Variable | HKA ≥177(n=49/70, 70%) | HKA <177(n=21/70, 30%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rate of survivala | 81.1% | 64.5% | .03* |

| Functionality (KSS) | 87.2±13.9 | 66.3±25.9 | .01* |

| Functionality (OKS) | 39.7±7.5 | 30.8±9.5 | .06 |

| Improvement in painb | 5.6±2.8 | 2.3±2.5 | .25 |

| Overall satisfaction | 8.53±1.89 | 5.73±2.84 | .01* |

HKA: Hip-Knee-Ankle; KSS: Knee Society Score; OKS: Oxford Knee Score.

The average duration of surgery was 34±3min. Regarding the complication rate, 17 patients (24.3%) suffered a disruption of the medial hinge when performing the osteotomy. All cases were diagnosed intraoperatively. None required treatment by additional fixation. These individuals followed a rehabilitation protocol with load limitation depending on the degree of disruption. Osteotomy consolidation was achieved in 100% of cases. No patient (0%) suffered infection, symptoms compatible with common peroneal nerve injury, or required unplanned reintervention.

DiscussionThe most important results of our study were that knee valgus osteotomy using the CW-HTO technique presented a survival rate of 87.6% at five years and 75.5% at 10 years of follow-up, good-excellent functional results (KSS 77.7/100 and OKS 35.6/48), good pain control (VAS 3.9/10) and high satisfaction (7.2/10). Furthermore, the varus malalignment of the extremity was significantly corrected (mean postoperative HKA angle 177.6° and MPTA 90.7°).

Knee valgus osteotomy is a classic joint preservation technique. In recent years, its use has increased thanks to virtual planning tools, the improvement of surgical instruments and the expansion of indications.2 In many cases, it allows knee prostheticisation to be deferred or avoided. In our series, we observed a survival rate of 87.6% at five years of follow-up and 75.5% at 10. Our result is compatible with the survival reported in a recent systematic review: 86–100%, 64–97%, 44–93% and 46–85% at five, 10, 15 and 20 years, respectively.11

The functional results of the patients operated on with CW-HTO in our study were good-excellent, also achieving a relevant reduction in pain. Berruto et al.,12 analysed 82 patients operated on using this technique and reported functional results similar to ours. Of the cases, 97.4% presented good-excellent values according to the Crosby-Insall scale and pain was reduced from 7.9±1.4 to 1.6±1.1. Many other authors7,13 also defend the effectiveness of OTA to achieve very good clinical results in individuals with osteoarthritis of the medial compartment and malalignment. We consider that, probably, for the patient the most relevant results are the functional ones. However, there is great heterogeneity in the literature in the scales used to report them, making it difficult to understand the results, compare between studies, and aggregate data.7 For this reason, we emphasise that in our study we have also assessed the patient's overall satisfaction with the procedure. Satisfaction with osteotomy was 7.2/10 (rising to 7.9/10 in those who did not require conversion to TKA).

Knee valgus osteotomy is based on moving the mechanical axis of the limb laterally to reduce the load on the medial compartment.1 In the patients in our study, the mean HKA angle went from 170.1° to 177.6° (p value .01) and the MPTA angle from 8° to 90.7° (p=.04). However, 30% (21/70) of patients had a postoperative HKA <177°. Furthermore, undercorrection was associated with a lower survival rate (64.5 vs. 81.1%, p=0.03), lower functionality according to the KSS scale (66.3 vs. 87.2, p=.01) and lower satisfaction (5.73 vs. 8.53, p=.01) (Table 3). The correction of the alignment of the limb has been reported as a determining element to generate good results after a high tibial osteotomy (HTO).14 The high rate of patients with undercorrection after CW-HTO observed in our study is probably related to multiple factors. Firstly, it could be due to technical errors made during the planning or execution of the surgery. Murray et al.1 argued that CW-HTO is technically demanding and, therefore, could be associated with less predictable results than MO-HTO. Secondly, the final alignment objective was not systematically hypercorrection seeking the Fujisawa point 10, but was established on an individual basis based on the indication, severity of the disease and axis of the contralateral limb.3 Finally, despite the undercorrection in the HKA, a correct correction of the MPTA (90.7±3.9°) was achieved in the majority of patients. It could be that, in some cases, part of the limb malalignment was due to femoral deformity. However, it must be remembered that a second osteotomy should not be added to any femoral deformity.3 Double osteotomy significantly increases surgical aggression and is only recommended when the femoral deformity is relevant and performing the entire correction at the tibial level affects the obliquity of the interline.15

It has been reported that CW-HTO has a tendency to decrease the tibial slope, not affect the height of the patella and shorten the limb, while MO-HTO raises the tibial slope, lowers the patella and lengthens the limb.16–18 The dysmetria generated is not usually clinically relevant, but it could be a problem if it is added to a previous discrepancy.3 Likewise, in our study, the patients did not show any change in patellar height (.95 vs. .98, p=.33). On the other hand, the tibial slope presented a slight but statistically significant decrease (9.3 vs. 7.5°, p=.01). The advantages of CW-HTO are the potential superiority in consolidation when contacting bone-bone and the probable lower economic cost compared to MO-HTO due to the use of implants and/or graft. Furthermore, CW-HTO is considered more technically demanding1,19 Some of the reasons are that its surgical approach may require identifying and protecting the common peroneal nerve, performing disarticulation or resection of the proximal tibiofibular joint, and it requires two bone cuts. Despite its good results, CW-HTO has an intraoperative complication rate of 5.5% and a postoperative complication rate of 6.9%.20 The most frequent are disruption of the cortical hinge (29.4%), loss of correction (10%), injury to the common peroneal nerve (6%), infection (2%) and nonunion (1.2%)1. It is notable that, despite being a specific complication of CW-HTO, in our series no patient suffered symptoms compatible with common peroneal nerve injury. To achieve this, we consider it necessary to disarticulate the proximal tibiofibular joint without having to identify the common peroneal nerve, instead of a proximal fibular osteotomy with identification and protection of the nerve.21 However, 17 patients (24.3%) suffered a disruption of the medial hinge. All cases were intraoperative findings that did not require additional fixation, although the rehabilitation protocol was modified by limiting the load. Of these subjects, 100% consolidated without requiring reoperation.

This study is not without limitations. First of all, it is an observational and non-comparative study. Likewise, the retrospective nature of the work has limited the ability to collect some variables. Secondly, radiological measurements were performed only once by a member of the research team. But, on the other hand, the researcher who performed the measurements was qualified (a resident in orthopaedic surgery) and only patients who had strictly correct radiographs (anteroposterior and knee profile and telemetry) were included. Third, we do not have preoperative functionality data. They would have been useful to analyse the evolution after the intervention. However, we consider that a strength of the study is the extensive collection of variables that has allowed us to evaluate the postoperative outcome of CW-HTO in a holistic manner. Survival (conversion rate to TKA), clinical (KSS, OKS, pain and satisfaction) and radiological (HKA, MPTA, patellar height and tibial slope) outcomes were assessed.

In conclusion, knee valgus osteotomy using the CW-HTO technique may be a useful option for patients with knee osteoarthritis and varus limb. It allows correcting varus malalignment of the extremity, offering good-to-excellent functional results, good pain control, high satisfaction and an acceptable medium-long term survival rate. However, it presents a non-negligible risk of undercorrection, which is associated with a lower survival rate, functionality and satisfaction. Furthermore, a high rate of disruption of the medial hinge stands out.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our centre. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards established in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consentAs this was a retrospective observational study, exemption from informed consent was obtained from the Ethics Committee of our centre.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, material preparation, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RF, OP, and JF and they all commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Likewise, they have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the authors’ order of presentation.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.