Low socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with a higher risk of fragility fractures, as well as higher mortality in the first-year post-fracture. The SES variables that have the greatest impact are educational level, income level, and cohabitation status. Significant disparities exist among racial and ethnic minorities in access to osteoporosis screening and treatment.

In Spain, a higher risk of fractures has been described in people with a low-income level, residence in rural areas during childhood and low educational level. The civil war cohort effect is a significant risk factor for hip fracture. There is significant geographic variability in hip fracture care, although the possible impact of socioeconomic factors has not been analyzed. It would be desirable to act on socioeconomic inequalities to improve the prevention and treatment of osteoporotic fractures.

El estatus socioeconómico (ESE) bajo se asocia con un mayor riesgo de fracturas por fragilidad, así como con una mayor mortalidad en el primer año posfractura. Las variables de ESE que tienen un mayor impacto son el nivel educativo, el nivel de ingresos y el estatus de cohabitación. Existen disparidades significativas entre las minorías raciales y étnicas en el acceso al cribado y tratamiento de la osteoporosis.

En España se ha descrito un mayor riesgo de fracturas en personas con un nivel de ingresos bajo, residencia en el ámbito rural durante la infancia y bajo nivel educativo. El efecto cohorte de la Guerra Civil es un factor de riesgo significativo de fractura de cadera. Existe variabilidad geográfica significativa en la atención a la fractura de cadera, aunque no se ha analizado el posible impacto de factores socioeconómicos. Sería deseable actuar sobre las inequidades socioeconómicas para mejorar la prevención y tratamiento de las fracturas osteoporóticas.

Osteoporosis is a disease that decreases bone mass and its resistance, which increases the risk of fragility fractures, the main clinical consequence of the disease. Its prevalence in the developed world has increased significantly in recent decades due to the progressive increase in life expectancy.

As a result, in 2017 in the five countries with the largest population in the European Union, together with Sweden (EU6), there were an estimated 2.7 million fragility fractures, with an annual cost of 37.5 billion euros and a loss of one million quality-adjusted life years (QALY). The projection for the year 2030 is an increase of 23%, which translates into 3.3 million fragility fractures, with an increase in associated health spending of 27%.1

Specifically in Spain, according to the recent SCOPE 21 report, osteoporosis affects 5.4% of the population, and in the age group over 50 years, 22.6% of women and 6.8% of men have osteoporosis. In 2019, it is estimated that 285,000 new fragility fractures occurred, which would be equivalent to 782 fractures daily (or 33 new fractures per hour).

Also, the expected aging of the population for Spain in the next decade exceeds the European Union average, so that the number of people over 75 years of age is expected to grow in 2034 by 37.7% in the case of men and 28.6% in the case of women. As a consequence, an increase in fragility fractures of 29.6% is expected, reaching 370,000 new fragility fractures in a decade.

The healthcare cost of osteoporotic fractures in Spain is high and accounted for 3.8% of total healthcare expenditure in 2019 (4.3 billion euros in direct costs, excluding the loss in quality of life years), a percentage somewhat higher than the average of the European Union countries (3.5%), which puts Spain in twelfth place among the European countries with the highest economic cost due to this complication.2 These economic data are particularly useful for designing health policies that facilitate early diagnosis and treatment of the disease, providing primary and secondary prevention of fractures.

The impact that economic inequality has on certain prevalent chronic diseases is also of great interest. For example, in a recent study conducted in a Danish population over 16 years of age (n=4,555,439), it was found that among 29 chronic diseases studied, osteoporosis ranked fourth among those with the greatest differences in socioeconomic level.3

According to 2021 data, economic inequality in Europe (measured as income inequality, or Gini index) has great variability, with a marked north-south gradient, with the lowest inequality found in countries such as Norway, Finland, Belgium or the Netherlands and the highest in Southern European countries (Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece). In the ranking of countries with the greatest inequality, first place goes to the United Kingdom, with Spain occupying third place behind Italy.

When broad disposable income is considered, which also takes into account public services such as education, health and housing, Spain's difference in the inequality index is reduced compared to the countries of northern and central Europe, on a par with Germany.4

Regarding osteoporosis, economic inequality may affect different aspects: e.g. inequities in access to diagnostic tests (bone densitometry), medical treatment of the disease (access to anti-osteoporotic treatments), and surgical treatment of fractures and their complications. Furthermore, it could affect the epidemiology of the disease itself (incidence and prevalence).

This review aims to investigate the socioeconomic factors that may contribute to specific regional differences in the incidence and prevalence of osteoporosis, and fragility fractures, together with their medical and surgical management, with particular attention paid to the existing data in Spain.

MethodsA narrative, non-systematic review. A search was conducted in the main databases and repositories (PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar) focusing on the last 10 years (2013–2023). The search terms used were: socioeconomic status, inequality, health inequity, osteoporosis, osteoporotic fractures.

Indicators of socioeconomic statusIn the literature there are a variety of variables indicating socioeconomic status (SES), which can be divided into individual or area SES measures. The most common individual variables are educational level, income, and occupation. Area or population census-based measures make it possible to evaluate socioeconomic deprivation at local or national level. They can consist of a single variable (e.g. average income of a family in a given area) or composite measures of SES with different domains (e.g. income; employment; health; education; housing; or crime indicators) that are combined into a multiple deprivation index.5

Socioeconomic status and incidence of fragility fracturesInternational studiesPrevious studies carried out in national fracture registries in France, the United Kingdom, Denmark and Israel found there was an association between lower socioeconomic status and a higher risk of hip fracture. Thus, in France, a 3% higher risk is described in the highest quartile of social deprivation estimated by the European Deprivation Index (EDI) compared to the lowest quartile.6 This EDI index is a construct obtained from weighted variables in a given census area that include: home ownership; over-population; presence of a bathroom/shower; car ownership; single-parent families; educational level; employment and foreign nationality. In the United Kingdom, in a study of 747,000 hip fractures recorded over a 14-year period, the incidence of hip fracture was higher in areas with a higher rate of multiple, social deprivation. This effect was greater in the case of men, in whom the risk increased by 50%, compared to women, in whom economic deprivation increased the incidence by 17%.7

In Denmark, a registry of nearly 190,000 fractures (hip, humerus or wrist) in people over 50 years of age, analysed during the 1995–20208 period found that the risk of hip fracture was lower (OR: .78; 95% CI: .72–.85) in subjects in the highest income quintile, as well as in urban environments or less than 30min from cities with more than 3000 inhabitants. Furthermore, the risk was higher among unmarried, widowed or divorced individuals compared to married individuals.8

Valentin et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 61 studies carried out in 26 different countries,9 including individual data from 19 million people over 50 years of age. Educational level, income, occupation, and cohabitation status were collected individually as indicators of SES. The effects of age, sex, BMI and health habits (smoking, alcohol consumption and physical inactivity) were analysed as covariates. They found that patients with low SES had a 27% higher risk of fragility fracture than those with high SES (RR: 1.27; 95% CI: 1.12–1.44). This association was consistent across all individual measures of SES, although the highest risk was found in those who lived alone versus those who cohabited (RR: 2.37; 95% CI: 1.88–2.98). A low BMI and unhealthy habits were present as mediators of this association.9

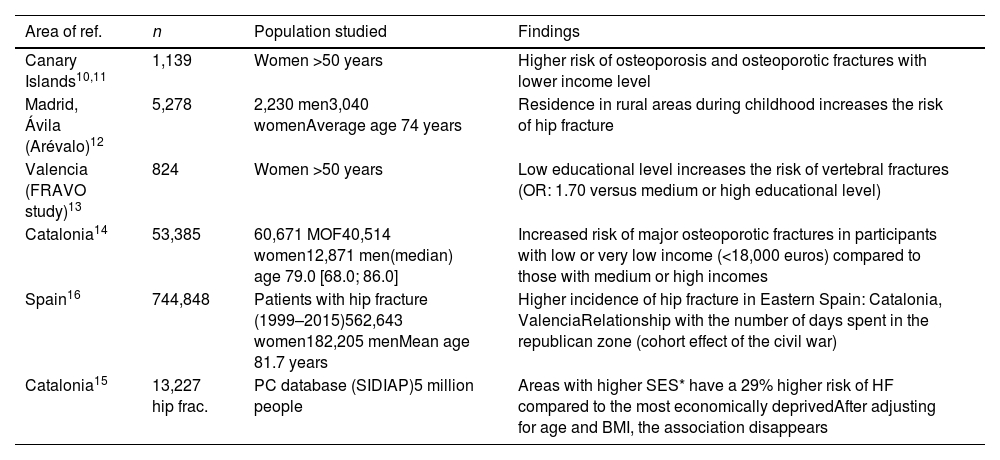

Studies in SpainFew studies have addressed the relationship between SES and osteoporosis and fractures and they are summarised in Table 1.

National studies which link socioeconomic status with osteoporotic fracture risk.

| Area of ref. | n | Population studied | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canary Islands10,11 | 1,139 | Women >50 years | Higher risk of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures with lower income level |

| Madrid, Ávila (Arévalo)12 | 5,278 | 2,230 men3,040 womenAverage age 74 years | Residence in rural areas during childhood increases the risk of hip fracture |

| Valencia (FRAVO study)13 | 824 | Women >50 years | Low educational level increases the risk of vertebral fractures (OR: 1.70 versus medium or high educational level) |

| Catalonia14 | 53,385 | 60,671 MOF40,514 women12,871 men(median) age 79.0 [68.0; 86.0] | Increased risk of major osteoporotic fractures in participants with low or very low income (<18,000 euros) compared to those with medium or high incomes |

| Spain16 | 744,848 | Patients with hip fracture (1999–2015)562,643 women182,205 menMean age 81.7 years | Higher incidence of hip fracture in Eastern Spain: Catalonia, ValenciaRelationship with the number of days spent in the republican zone (cohort effect of the civil war) |

| Catalonia15 | 13,227 hip frac. | PC database (SIDIAP)5 million people | Areas with higher SES* have a 29% higher risk of HF compared to the most economically deprivedAfter adjusting for age and BMI, the association disappears |

BMI: body mass index; HF: hip fracture; MOF: major osteoporotic fractures; PC: primary care.

A cross-sectional study carried out in the Canary Islands in 1139 postmenopausal women >50 years without a previous history of osteoporosis found that in the group of women whose family income per capita/family member was less than 6365 euros per year (considered at that time as a poverty indicator) had a 35% higher risk of suffering from densitometric osteoporosis compared to women of medium or high socioeconomic status, after adjusting for variables such as BMI and age.10 Also in this group there was a 45% higher risk of fragility fractures and, in particular, a much higher risk of radiological vertebral fractures (101%). The same authors, in a subsequent study involving 1229 postmenopausal women, found a greater risk of vertebral fractures in women living in a rural environment, which is also associated with a greater risk of poverty.11

- -

In a cohort study carried out on 5278 subjects (2238 men and 3040 women) over 65 years of age (average age 74 years) belonging to three geographical areas of central Spain with different socioeconomic levels: two urban areas, Getafe – working class –, central Madrid (Lista) – upper class/liberal professionals – and Arévalo, a rural area 125km from Madrid, the prevalence of hip fracture was 3.1%, higher in urban areas (Getafe 3.6%, central Madrid 4.2%) compared to rural areas (1.9%, p<.001). The adjusted mortality was higher in the group with hip fracture 1.40 (95% CI: 1.15–1.71; p=.001). The variables associated with a higher risk of hip fracture in the univariate analysis were age and female sex (p<.001), low BMI (p=.01) as well as childhood in a rural environment (p=.007) and “single” marital status (p=.004). In the multivariate analysis, it was found that advanced age, low BMI, and residence in a rural environment during childhood were significantly and independently associated with the risk of hip fracture.12

- -

A population-based cross-sectional study carried out in the region of Valencia in 824 postmenopausal women over 50 years of age investigated the prevalence of osteoporosis and vertebral fractures, as well as their risk factors (FRAVO study).13 The educational level was analysed (three categories: no studies, primary studies, secondary/university studies). The prevalence of vertebral morphometric fractures was 21.3%. Low educational level was a risk factor for vertebral fractures, both in the bivariate analysis and in the multivariate analysis: almost double the risk in the group of women without education compared to the group with secondary or university education (OR: 1.70; 95% CI: 1.06–2.72; p=.028).

- -

More recently, an analysis of more than 60,000 major osteoporotic fractures in people over 50 years of age, registered in the Catalan Health System in the period 2018–2019, found that among the factors that were associated with a higher risk of fracture, in addition to female sex, advanced age, tobacco and alcohol, as well as some frequent comorbidities, a low SES was found (estimated by the level of per capita income). Specifically, a low or very low-income level (below 18,000euros/year) poses a greater risk of osteoporotic fractures compared to medium (>18,000euros/year) or high incomes (>100,000euros/year).14

- -

In contrast to the studies described above, a retrospective cohort study carried out in an urban area of Catalonia, with coverage of five million people, analysed the relationship of a validated measure of SES composed from data obtained from Health Care Records Primary (proportion of unemployed, temporary and manual workers, educational level achieved) estimates for each urban area on the incidence of hip fractures in the period 2009–2012. The risk of hip fracture was found to be 30% higher in those areas with higher estimated SES. Differences in sex and age composition, as well as a higher prevalence of obesity in areas with greater economic deprivation could have explained this higher risk.15

In a national retrospective analysis of 744,848 patients with hip fracture collected over a 17-year period based on data obtained from the Minimum Data Set provided by the Ministry of Health (TREND-HIP study), a large variability was found in the age-adjusted incidence among the different autonomous communities (AC), with the highest rates in Catalonia and Valencia (363/100,000 persons-years) and the lowest in the Canary Islands (214/100,000 persons-years), thus confirming the existence of an east-west gradient. In a second part, an ecological study was conducted to investigate the possible factors associated with this variability (VAR-HIP study). Among the factors studied, socioeconomic indicators provided by the National Institute of Statistics (INE) were collected. These included: the volume of water registered and distributed (litres/person and day); volume of wastewater (litres/person/day); average level of income per person; risk of poverty or social exclusion (%); households by housing ownership; and average number of vehicles per person. Genetic factors (mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosome haplotypes), demographic and climatic and environmental factors were also included, as well as the number of days that each A.C. remained on the Republican side (more economically disadvantaged than the national side) during the years of the civil war. A significant correlation was found with genetic factors (haplotypes H and J2); demographic (birth rate and fertility) factors; climatic (average annual precipitation); percentage of smokers; and the cohort effect of the civil war, which explained 96% of the variability. The impact of the economic deprivation suffered during the civil war years (1936–1939), more pronounced in certain regions of Spain (Catalonia and Valencia remained on the Republican side until the end of the war), could have negatively affected the acquisition of the peak bone mass of large sectors of the population and, therefore, contributed to the increased risk of hip fracture observed.16

More recently, the PREFRAOS study, carried out in the primary care setting, retrospectively investigated the prevalence of fragility fractures in 665 subjects >70 years old recruited in 30 centres belonging to 14 ACs. The fundamental finding of the study was the high prevalence of fragility fractures (overall 17.7%; women 24% and men 8%) with more than 50% of subjects not receiving treatment for osteoporosis. Although individual SES parameters were collected (educational level and marital status), it is not described that they made any type of difference in the results found.17

Influence of socioeconomic status in the diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracturesIt is also relevant to determine whether socioeconomic status (SES) can influence the management of osteoporosis and fragility fractures. Previous international studies have shown important disparities that affect: (1) the primary prevention of fractures; (2) the time of fracture surgery; and (3) the pharmacological treatment chosen for secondary prevention.18,19

Regarding the first point, previous studies in the US have shown that black women are less likely to be screened for osteoporosis than white women. These differences remain even after adjusting for socioeconomic level, and among other reasons, the false assumption of a lower risk of osteoporosis in the black race.19 A study conducted in white and African American women over 65 years of age found differences in knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs in women with osteoporosis that could influence racial disparities in bone health, indicating a need for greater education and knowledge of osteoporosis in African American women.20 A recent systematic review confirmed in 14 out of 16 studies analysed that racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to undergo bone densitometry for osteoporosis screening.21

Although there is very little data on the prevalence of osteoporosis in sub-Saharan Africa, there appears to be marked variability depending on the country and area of residence.22 In urban South Africa, the prevalence of osteoporosis of the femoral neck is the highest of all studies conducted in Africa, comparable to that of white women in the USA, and much higher than that of black American women, or white British women. A recent study, obtained from the incidence of hip fractures in South Africa in 2020, predicted that the incidence will at least double in the next three decades,23 partly due to progressive aging, but also to the high prevalence of chronic infection by HIV, which affects 25% of South African women. A recent study has shown that bone loss associated with menopause is greater in women living with HIV compared to those living without the virus.24

A study of 926 South Korean women over the age of 50 found that those with poor knowledge of osteoporosis and lower SES (including those who lived alone and with a lower annual income level) were less likely to be screened and treated for osteoporosis.25 In a cohort of 36,965 subjects in the State of Indiana (USA), those with a diagnosis of osteoporosis or fragility fractures after the age of 50 were analysed. Black men using the public health system were found to be less likely to receive medical treatment for osteoporosis.26

Regarding the timing of surgery after a hip fracture, the recommendations of the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons indicate that surgery should be carried out in the first 48h to optimise evolution and avoid complications. Previous studies have shown that black and Asian patients are more likely to experience delays of more than 2 days in surgery compared to white patients, even after adjusting for level of socioeconomic deprivation.27,28

In Spain, a prospective cohort study, carried out in 45 hospitals in 15 different autonomous regions, analysed 997 consecutive patients who were admitted to hospital during the period from June 2014 to June 2016 for a hip or proximal femur fracture. Seventy-six point seven per cent were women and with an average age of 83.6 years. The study revealed a significant delay in surgical treatment from admission (mean 59h) and from the start of rehabilitation treatment (mean 61.9h). Furthermore, the percentage of patients who did not receive any anti-osteoporotic treatment for secondary fracture prevention at discharge was unacceptably high (80%). Although the educational level was collected (basic or primary studies in 67.9% and 20% with no studies), it was not analysed whether this SES indicator was a discriminating factor in the observed results.29

More recently, in a cross-sectional analysis of data from the cohort belonging to the National Registry of Hip Fractures (RNFC for its initials in Spanish), in the period from January 2017 to May 2018, the data of 13,839 patients admitted for hip fracture were analysed in 61 hospitals in 15 ACs. Seventy-five point eight per cent were women and the average age was 86.7 years.

This study revealed the existence of important differences in the management and treatment of hip fractures by different autonomous communities. A significant delay in surgical treatment was demonstrated (mean 70h, only 43% of patients operated on before 48h), but with notable differences between communities such as Madrid (71.2h) and Catalonia (59.6h). Significant differences were also found in the average length of stay, early mobilisation and mortality, among other indicators.30 Strikingly, the study did not analyse the impact of SES on the variability of results observed between the different ACs.

In a continuation of the same study from the National Registry of Hip Fractures (RFNC), 18,262 patients were analysed, 24% of whom lived in nursing homes. It was observed that the management of patients in this group differed significantly from those who lived in the community: they were more likely to receive conservative treatment and less likely to receive anti-osteoporotic or vitamin D treatment, or to be referred to geriatric rehabilitation units. They also had a higher mortality rate in the first month after hospital discharge.31

Regarding medical treatment after recent hip fracture for secondary prevention of new fractures, a retrospective analysis was conducted of a cohort of 30,965 patients aged 65 or older, who were hospitalised for hip fracture in the Valencia region during the period from January 2008 to December 2015. Multiple logistic regression was used to investigate the risk factors associated with the presence of prescription of anti-osteoporotic drugs 3 months after hospital discharge. Once again, an excessively high treatment gap was confirmed, which also worsened significantly during the study period: only 28.9% of patients received anti-osteoporotic medical treatment in 2009, a percentage that worsened in 2015 (16.4%). Significant variability was observed in this percentage in the different health areas studied (between 11% and 40.9%), although in almost all of them (20/24) the decrease in the percentage of patients treated at the end of the study period was confirmed. Furthermore, there were significant differences in the choice of drug between the different areas. The sociodemographic factors associated with a greater probability of receiving medical treatment were female sex, age (<85 years) and the presence of a diagnosis or previous treatment for osteoporosis, but variables indicative of SES were not analysed.32

Mortality and quality of life studies related to health after fragility fracturesMortality after a hip fracture increases between 14% and 36% in the first year after the fracture, with the first 3 months after the fracture being when the increase in mortality risk is greatest (up to 8 times). Although the excess risk of mortality decreases later, it does not equal that of controls of the same age. Likewise, the decrease in quality of life is affected after the fracture with a decrease of 22–42% in the first year after a hip fracture.

Valentin et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 24 studies in 15 countries that included more than one million patients with hip fracture. The total risk of mortality in the first year after fracture was 24% higher in patients with low SES compared to those with high SES (RR: 1.24; 95% CI: 1.19–1.29). This increased risk in the low SES group was consistently observed for all individual SES measures and for all countries included in the study, which had marked differences in social and health policies.33

In Spain, the aforementioned study by Castillón et al. demonstrated great variability between ACs in in-hospital mortality after hip fracture, as well as in 30-day mortality. The highest mortality was found in both cases in the Basque Country (8.4% and 12.5%, respectively) with the lowest in the Balearic Islands, the Canary Islands and the region of Murcia (<3%). No consideration was made regarding the socioeconomic level of the different ACs and the potential effect on the results, despite the genuine interest that this analysis could have had, as recognised by the authors themselves.

Regarding health-related quality of life (HRQoL) after fractures, a population-based study conducted in Denmark in 12,839 women and men >50 years with fractures and 91,246 controls, found significant deficits in both the physical and mental components of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) questionnaire in fractured patients. The fractures with the greatest impact on HRQOL were hip and vertebral fractures with deficits up to 5 years post-fracture. When they analysed the specific effect of SES on HRQOL in fracture patients, the group with low SES had a greater deficit in the mental component of the SF-12 questionnaire than the group with high SES, but not in the mental component.34

ConclusionTo conclude, there is evidence that low SES is associated with a higher risk of fragility fractures, as well as with higher mortality in the first-year post-fracture. SES variables that have been linked to increased risk of fractures are educational level, income level, and cohabitation status. In Spain, some studies have also found a greater risk of fractures in people with a low-income level; those residing in rural environments during childhood; those with a low educational level, and also those affected by the intense economic deprivation suffered in Spain during the civil war, particularly in autonomous communities of the Eastern regions of the peninsula.

When designing health and social policies to improve the prevention and treatment of osteoporotic fractures, effective action on socioeconomic inequalities should be considered. In particular, recent initiatives such as those of the RNFC or fragility fractures (SEIOMM-REFRA)34 should include analysis of these indicators to facilitate adequate resource planning.35

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical considerationsBibliographic review work of clinical trials or meta-analyses already published in indexed scientific journals that comply with all ethical regulations.

FundingThis study had no funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.