Necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTI) are increasing, posing a significant risk of morbidity and mortality. Due to nonspecific symptoms, a high index of suspicion is crucial. Treatment involves a multidisciplinary approach, with broad-spectrum antibiotics, early surgical debridement, and life support. This study analyzes the characteristics, demographics, complications, and treatment of NSTI in a hospital in Madrid, Spain.

MethodsA retrospective observational study was conducted, including all surgically treated NSTI patients at our center from January 2016 to December 2022, examining epidemiological and clinical data. The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) was prospectively calculated for all patients.

ResultsTwenty-two patients (16 men, 6 women, mean age 54.8) were included. Median time from symptom onset to emergency room visit was 3.5 days. All reported severe treatment-resistant pain; sixteen had fever exceeding 37.8°C (72.7%). Skin lesions occurred in twelve (54.5%), and thirteen had hypotension and tachycardia (59.1%).

Treatment involved resuscitative support, antibiotherapy, and radical debridement. Median time to surgery was 8.25h. Intraoperative cultures were positive in twenty patients: twelve Streptococcus pyogenes, four Staphylococcus aureus, one Escherichia coli, and four polymicrobial infection. In-hospital mortality rate was 22.73%.

ConclusionsWe examined the correlation between our results, amputation rates and mortality with LRINEC score and time to surgery. However, we found no significant relationship unlike some other studies. Nevertheless, a multidisciplinary approach with radical debridement and antibiotic therapy remains the treatment cornerstone. Our hospital stays, outcomes and mortality rates align with our literature review, confirming high morbimortality despite early and appropriate intervention.

Las infecciones necrotizantes de partes blandas (NSTI), suponen un riesgo significativo de morbimortalidad. Debido a sus síntomas inespecíficos, es crucial mantener un alto índice de sospecha. El tratamiento implica un enfoque multidisciplinar con antibióticos de amplio espectro, desbridamiento quirúrgico precoz y radical y soporte vital. En este estudio, analizamos las características clínicas y demográficas, complicaciones y el tratamiento de las NSTI en un hospital de Madrid, España.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional retrospectivo incluyendo a todos los pacientes con NSTI intervenidos en nuestro centro desde enero de 2016 hasta diciembre de 2022, donde se analizaron los datos epidemiológicos y clínicos. La escala Laboratory risk indicator for Necrotizing fasciitis (LRINEC) se calculó de manera prospectiva para todos los pacientes.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 22 pacientes (16 hombres, seis mujeres; edad media 54,8). El tiempo medio desde el inicio de los síntomas hasta la consulta en urgencias fue de 3,5 días. Todos los pacientes presentaban dolor resistente al tratamiento y 16 presentaban fiebre mayor de 37,8°C (72,7%). Presentaban lesiones cutáneas 12 pacientes (54,5%) y 13 hipotensión y taquicardia (59,1%). El tratamiento consistió en soporte vital, antibioterapia y desbridamiento radical. El tiempo medio hasta la cirugía fue de 8,25 horas. Los cultivos intraoperatorios fueron positivos en 20 pacientes: 12 Streptococcus pyogenes, cuatro Staphylococcus aureus y uno Escherichia coli. En cuatro casos la infección fue polimicrobiana. La mortalidad intrahospitalaria fue del 22,73%.

ConclusionesEl enfoque multidisciplinar, incluyendo desbridamiento radical y terapia antibioterapia, sigue siendo la piedra angular del tratamiento de las NSTI. En este estudio no encontramos correlación significativa entre nuestros resultados, tasas de amputación y mortalidad con la puntuación de la escala LRINEC ni el tiempo hasta la cirugía. Nuestros resultados, estancia hospitalaria y tasa de mortalidad coinciden con lo reportado por la literatura, confirmando la alta morbimortalidad de estas infecciones a pesar del tratamiento precoz.

Necrotizing soft tissue infections (NTSI) are rapidly progressive and destructive infections affecting the skin, subcutaneous tissue, fascia and muscle, ultimately leading to necrosis with high mortality and long-term morbidity. Currently, the estimated incidence of 0.045 cases per 1000 individuals annually.1,2 The current mortality rate ranges from 7.6 to16.6%.3,4

A high index of suspicion is crucial, since symptoms are nonspecific, with fever and treatment-resistant pain being the most common manifestations. Additionally, approximately half of the patients exhibit associated skin lesions. Common risk factors include diabetes mellitus, obesity, immunosuppression or alcohol abuse. Nevertheless, cases of young adult patients without any known risk factors have also been documented.5

The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) is a scoring system derived from carious common laboratory values, including white blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, creatinine and glucose concentrations. It is believed to have a high positive predictive value.2,3 Additionally, the presence of air or bubbles, along with thickening of the fascia, are findings that further support the diagnosis.4

Treatment should be accomplished by a multidisciplinary team and is based on broad-spectrum antibiotics, early surgical debridement and life support therapy.

The objective of this research is to identify clinical, analytical and imaging factors that contribute to the early diagnosis and treatment of patients with NSTIs. We conducted a retrospective analysis of patient characteristics, clinical presentations, treatments, complications, mortality, and their correlation with the LRINEC score at our hospital.

Patients and methodsA retrospective study was conducted, including all patients admitted to our hospital in Madrid (Spain) between January 2016 and December 2022, who underwent surgical debridement due to a necrotizing infection. Data, including demographics, pre-existing comorbidities, symptoms, vital signs, time to surgery, microbiology and clinical outcome were collected and analyzed. Clinical outcomes, such as pain scores on the visual analog scale, ability to return to work and the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score, were recorded one year after the infection.

This study was conducted following the ethical standards outlined in the Helsinki Declaration and resolution 008430 of 1993, and it was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution (internal approval code 24/005-E). Additionally, all patients included in this study were informed about it, and their consent to participate was obtained.

The LRINEC scale was calculated for each patient upon admission (Table 1).6 All patients underwent early surgical debridement and received immediate broad-spectrum antibiotics, which were deescalated based on culture results afterwards.

Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis scale (LRINEC).

| Variables | Value | Punctuation |

|---|---|---|

| C reactive protein (mg/mL) | <150 | 0 |

| ≥150 | 4 | |

| White blood (cell/mm3) | <15 | 0 |

| 15–25 | 1 | |

| >25 | 2 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | >13.5 | 0 |

| 11–13.5 | 1 | |

| <11 | 2 | |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | ≥135 | 0 |

| <135 | 2 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ≤1.6 | 0 |

| >1.6 | 2 | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | ≤180 | 0 |

| >180 | 1 |

LRINEC: low risk<6; moderate risk 6–7; high risk>7. Reference values: CRP<10mg/mL, white blood cell 4–10.5/mm3, hemoglobin 12–16g/dL, sodium 135–145mmol/L, creatinine 0.51–0.95mg/dL, glucose 60–100mg/dL.

Continuous data were summarized as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile (IQ) range while categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and Fisher's exact probability tests through the SPSS software.

The authors, or their immediate families, and any research foundation with which they are affiliated did not receive any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

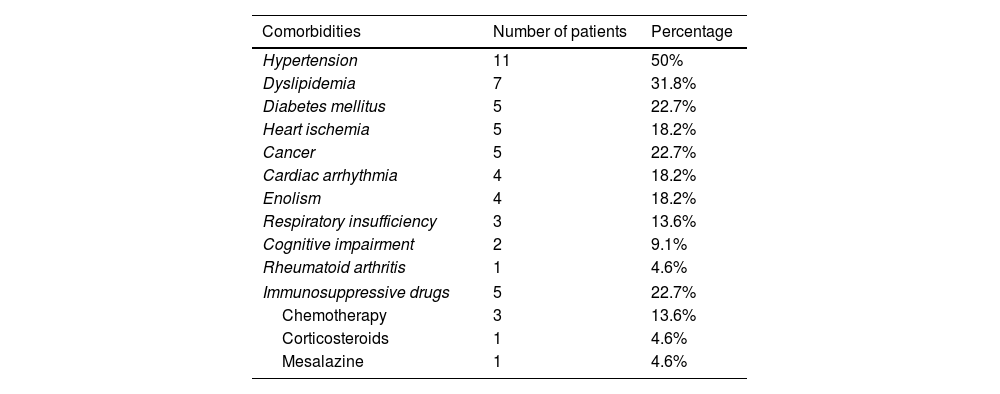

ResultsTwenty-two patients were included in the study, comprising sixteen men and six women. The mean age was 54.8 years (SD14.2). Among the participants, five had diabetes (22.7%), four were active alcoholics (18.2%) and five were under immunosuppressive therapy (22.7%): three patients were undergoing chemotherapy, one was on mesalazine and one was taking prednisone for rheumatoid arthritis (Table 2).

Comorbidity.

| Comorbidities | Number of patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Hypertension | 11 | 50% |

| Dyslipidemia | 7 | 31.8% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 | 22.7% |

| Heart ischemia | 5 | 18.2% |

| Cancer | 5 | 22.7% |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 4 | 18.2% |

| Enolism | 4 | 18.2% |

| Respiratory insufficiency | 3 | 13.6% |

| Cognitive impairment | 2 | 9.1% |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | 4.6% |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | 5 | 22.7% |

| Chemotherapy | 3 | 13.6% |

| Corticosteroids | 1 | 4.6% |

| Mesalazine | 1 | 4.6% |

Lower limbs were affected in fifteen patients (68.2%), while upper limbs were affected in seven (31.8%). Regarding the side affected, there was a higher incidence on the left side compared to the right side, with sixteen and nine cases, respectively.

The median time between symptom onset and emergency room (ER) admission was 3.5 days (range 1–10). However, eight patients (36.4%) had sought medical consultation previously due to an event, such as blunt soft tissue trauma or an insect bite, which could have triggered the entire process (Fig. 1). All patients reported severe pain that was refractory to treatment, and sixteen of them (72.7%) also presented with a fever exceeding 37.8°C. Nine patients (40.9%) had experienced mild trauma in the affected area in the preceding days, and two patients (9.1%) had been stung by a wasp. Clinical findings are summarized in Table 3.

Clinical findings.

| Patient | Previous trauma or possible cause | Days until admission | Previous antibiotic treatment | Fever | Skin lesion | Blood press | Bpm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Massage | 7 | No | Yes | Erythema | 70/40 | 90 |

| 2 | No | 60 | Amoxi-clav | Yes | Erythema | 140/90 | 100 |

| 3 | Insect bite | 0 | No | No | No | 130/60 | 90 |

| 4 | Abscess | 11 | Levofloxacin | No | No | 130/60 | 90 |

| 5 | Blount trauma | 2 | No | Yes | No | 80/60 | 140 |

| 6 | Wound | 3 | Amoxi-clav | Yes | Wound | 100/50 | 90 |

| 7 | No | 1 | No | Yes | Erythema | 80/60 | 130 |

| 8 | No | 14 | No | No | No | 85/60 | 130 |

| 9 | Closed forearm fracture | 10 | No | Yes | No | 60/30 | 160 |

| 10 | Blount trauma | 2 | No | Yes | Erythema | 100/60 | 112 |

| 11 | Celullitis | 10 | No | No | Purple dots | 75/45 | 140 |

| 12 | Insect bite | 1 | No | Yes | Erythema | 100/60 | 110 |

| 13 | No | 3 | No | Yes | Venous ulcer | 90/60 | 120 |

| 14 | No | 2 | No | Yes | Erythema | 120/60 | 120 |

| 15 | Intestinal perforation | 3 | No | No | No | 70/60 | 100 |

| 16 | No | 1 | No | Yes | No | 140/80 | 100 |

| 17 | Physical exercise | 3 | No | Yes | No | 80/60 | 140 |

| 18 | Wound | 5 | No | Yes | Erythema | 70/50 | 70 |

| 19 | No | 4 | No | Yes | No | 110/90 | 90 |

| 20 | Wound | 7 | No | No | No | 110/80 | 130 |

| 21 | No | 20 | Amoxi-clav | Yes | Pustules | 90/60 | 130 |

| 22 | No | 6 | No | Yes | Erythema | 60/40 | 120 |

Upon admission to the ER, thirteen patients (59.1%) presented with hypotension and tachycardia. Twelve patients (54.5%) were hemodynamically unstable, requiring inotropic support drugs upon arrival, leading to their immediate admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

In terms of laboratory results, seventeen patients (66.7%) exhibited a white blood cell count exceeding 10,500/μL, with all patients showing neutrophilia along with elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin. Creatine kinase (CK) levels were elevated in thirteen patients (59.1%), and hyponatremia was observed in fourteen patients (63.6%).

Broad-spectrum treatment was initiated promptly, even though four of the patients (18.2%) had received antibiotics previously. Table 4 summarizes the antibiotic treatments administered to each patient.

Antibiotic treatment.

| Patient | Empirical antibiotics | Adjusted to cultures |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Meropenem+Linezolid+Clindamycin | Penicillin G |

| 2 | Meropenem+Daptomycin | Levofloxacin |

| 3 | Cefazolin+Gentamicin+Clindamycin | Penicilin G |

| 4 | Levofloxacin | Linezolid |

| 5 | Meropenem+Linezolid+Clindamycin | Penicillin+Clindamycin |

| 6 | Piperacillin-Tazobactam+Clindamycin | Levofloxacin |

| 7 | Meropenem+Linezolid+Clindamycin | Penicillin G+Clindamycin |

| 8 | Piperacilin-Tazobactam+Linezolid | Piperacilin-Tazobactam+Linezolid |

| 9 | Meropenem+Linezolid+Clindamycin | Penicilin G |

| 10 | Linezolid+Clindamycin+Ciprofloxacin | Penicilin G |

| 11 | Meropenem+Linezolid+Clindamycin | Meropenem+Cloxacilin |

| 12 | Ceftriaxone+Clindamycin+Doxycycline | Negative cultures |

| 13 | Ertapenem+Daptomycin | Penicilin G |

| 14 | Meropenem+Daptomycin+Clindamycin | Amoxi-clav |

| 15 | Meropenem+Daptomycin+Clindamycin | Meropenem+Daptomycin+Clindamycin |

| 16 | Ceftriaxone+Clindamycin+Daptomycin | Cloxacilin |

| 17 | Meropenem+Cloxacilin | Cloxacilin |

| 18 | Meropenem+Linezolid | Amoxi-clav |

| 19 | Meropenem+Linezolid | Metronidazole+Linezolid+Ceftazidine |

| 20 | Piperacilin-Tazobactam+Daptomycin+Clindamycin | Cloxacilin+Clindamycin |

| 21 | Meropenem+Daptomycin+Clindamycin | Ceftazidine+Cloxacilin+Amphotericine |

| 22 | Piperaciline-Tazobactam+Daptomycin+Clindamycin | Cloxacilin |

Radiographic studies were conducted for all patients: ultrasound in three cases, MRI in two, and CT scan in sixteen. The findings were nonspecific in all instances, showing edema and infiltration of subcutaneous tissue and fascia, consistent with infection or inflammation. Air bubbles were identified in one patient, and collections were found in two cases.

The diagnosis was confirmed based on the results from microbiological cultures of tissue samples obtained during the initial operative debridement. In seventeen patients (77.3%), the infection was monomicrobial. Streptococcus pyogenes was the predominant causative organism, isolated in twelve patients. Other microbes identified from tissue cultures included Staphylococcus aureus (four patients) or Escherichia coli (one patient). Polymicrobial infection was observed in only four cases. Only in one patient, who had received antibiotic therapy prior to ER admission, intraoperative cultures yielded negative results. No patients were diagnosed with fungal infection. We did not find significant differences in the clinical course based on the cause of the infection.

Radical debridement was carried out in all patients, being aggressive enough to control the infection while trying to minimize the sequelae (Figs. 1 and 2). A supracondylar amputation was immediately required in one patient (4.5%), and in two additional cases (9.1%), amputations were necessary following the initial debridement due to a poor clinical course: one patient underwent a shoulder disarticulation, while the other required a right hip disarticulation and left supracondylar amputation.

Median time between arrival at the ER and surgical debridement was 8.25h (IQ range: 3.7–50.8). We did not find any significant relationship between clinical course, (need for amputation, reinterventions, complications or mortality) and time to surgery. Second-look surgeries were necessary for eighteen patients (81.8%). Median number of reoperations was 3 (IQ range: 0.75–4). In ten cases (45.5%), the expertise of a plastic surgeon was required for soft tissue coverage and reconstruction (Fig. 3).

The main complications following surgery included heart failure (three patients, 13.6%), kidney failure (ten patients, 45.5%) and respiratory failure (six patients, 27.3%). The duration of hospital stay ranged from 1 to 71 days (median 22.5 days, IQ range 15.1–34.1). For those patients requiring ICU admission, the median duration of ICU stay was 13 days (IQ range 8.5–21.5). There were five in-hospital deaths in this series, accounting for a mortality rate of 22.7%.

The LRINEC score was prospectively calculated for all patients. Six patients were classified as low risk (27.3%), nine as moderate risk (40.9%%) and seven as high risk (31.8%). The clinical course of each group is summarized in Table 5.

The minimum follow-up period was one year. One patient died during follow-up due to cancer, which was already in an advanced stage when the necrotizing infection occurred. The mean score on the visual analog pain scale was 5.3 (SD 1.2) one year after the infection. The median Functional Independence Measure (FIM) score one year after the infection was 109 (95.5–119.5) out of 126, with a score of 112 (100–126) in patients younger than 50 years and 102 (95–115) in patients older than 50 years. Only seven patients were able to return to their previous jobs, however, five of them needed to adapt or change them.

DiscussionEpidemiologyCurrently, the incidence of NSTIs is estimated at 0.045 cases per 1000 annually, nearly double the incidence reported in 1999, which was 0.024 cases per 1000.1,2 This increase is likely associated with the rise in life expectancy and the prevalence of pre-existing comorbidities. Furthermore, factors such as the growing bacterial resistance and the use of immunosuppressive medications may be contributing to this upward trend.1 In this report, we present a series of 15 NSTI cases treated at our hospital over 6-year period, averaging 2.5 cases per year.

Diabetes mellitus is the most prevalent risk factor, present in up to 71% of infections (35.7% in our series).7 Kidney failure or drug abuse are common predisposing factors, but they are not present in our series.4 On the other hand, two patients in our series have a history of alcohol abuse, which is also believed to be a risk factor.7 Up to 40% of patients have no known risk factor, therefore, a high index of suspicion is critical.

There is a higher incidence in males over 50 years. Furthermore, some studies show more frequent involvement of lower limbs, as observed in our series, followed by the trunk and head.6,8–12

Clinical findingsAs previously indicated, clinical findings are nonspecific, making it difficult to differentiate from other processes. NSTI should be considered in patients who experiences a sudden worsening2 or in whom skin lesions progress despite antibiotic treatment.4

Pain is present in 60–100% of cases,13–15 generally associated with fever, and described as disproportionate to physical examination.2,4 Physical examination findings can be subtle, and visible external signs are often minimal. In order of frequency, the typical manifestations are edema (75%), erythema (72%) and blisters or necrosis (38%). “Red flags” include pain out of proportion, hemorrhagic bullae, skin anesthesia, rapid erythema progression, crepitus on physical exam or presence of gas in the soft tissues. The incidence of these “red flags” is 7–44% and is indicative of advanced disease requiring immediate surgery.7,16

The triggering event could be trauma, including non-penetrating trauma, minor injuries, surgical or traumatic wounds. In these cases, the onset of symptoms usually occurs a week after the event.11 However, in up to 50% of cases, there is no triggering event,17 as observed in 31.8% of our patients.

DiagnosisThere are no specific laboratory values or radiographic features in NSTIs. However, some findings could aid surgeons in early diagnosis. Leukocytosis, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, and increased muscle enzymes are common in these patients.17 Additionally, dehydration, metabolic acidosis and organ dysfunction reflect the severity of illness and should raise suspicion of the presence of a NSTI.4

Several scores have been developed to aid surgeons in stablishing the diagnosis. The LRINEC score is the most widely used, created by Wong et al. in 2004.6,18 This score incorporates white blood cell count, hemoglobin, sodium, glucose, serum creatinine, and serum C-reactive protein to aseess the likelihood of necrotizing fasciitis. In the original publication, a score equal to or greater than 6 had a positive predictive value (PPV) of 92% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 96%. However, in a more recent study involving 215 patients in Singapore, the PPV decreased to 40%, while the NPV remained at 95%.16 In our series, 27.3% of the patients were classified as low risk according to the LRINEC score. Therefore, although the LRINEC score can support the diagnosis, it should be used in conjunction with clinical suspicion and under no circumstances should it be a reason for treatment delay.

Ballesteros et al.6 described a series of 24 patients treated between 2001 and 2008 and suggested that a higher LRINEC score might be associated with the clinical course, amputation risk and hospital stay. Heng Pek et al.8 reported a series of 27 patients treated between 2006 and 2012 and observed that higher LRINEC score was associated with a higher risk of amputation and death, although it was not statistically significant. In our series, only three patients (one from de low-risk group and two from the medium-risk group) required amputation as a treatment. Furthermore, the number of deceased patients was higher in the high-risk group (three patients) compared to the medium and low risk group (one patient each). While these findings were not statistically significant, they suggest a potential relationship between a worse prognosis and a higher LRINEC score.

Furthermore, Wall et al.16,19 have demonstrated a NPV of 99% in patients with a serum sodium above 135mEq/L and a white blood cell count below 15,400/μL. However, 22.72% of patients in our series exhibited these laboratory findings, indicating that these parameters alone are not sufficient to rule out the diagnosis.

On the other hand, the role of radiology is limited. The lack of enhancement of the fascia is the most specific finding in MRI.2,15 Other typical findings include subcutaneous emphysema in plain radiographs, which is observed in only 17–30% of cases, and deep tissue infiltration, fluid and thickening of the fascia in MRI or CT.4 However, the delay caused by imaging outweighs its potential benefit.

The gold standard for diagnosis is intraoperative findings, which include gray necrotic muscle or fascia, purulent fluid (“dishwater”), lack of resistance to digital pressure against fascial planes (“finger test”) and lack of muscle bleeding or contraction.2,3,7 It is also crucial to identify the causative microorganism through intraoperative cultures. Polymicrobial NSTIs account for approximately 75% of cases in some studies, usually associated with multiple risk factors.7 However, in our study, only 18.18% of infections were polymicrobial. Monomicrobial infections are primarily caused by S. pyogenes infection and S. aureus,7 representing 72.73% of our cases.

TreatmentThe cornerstone of treatment is decompression and debridement of necrotic tissue as soon as possible since NSTIs have a rapid progression that can be life-threatening. This rapid progression is believed to be related to bacterial toxins, which produce an inflammatory response that led to microthrombosis, ischemia, tissue dysfunction and, consequently, greater dissemination of infection.2,7

The term “radical debridement” is not clearly defined. It is recommended to remove all necrotic and devitalized tissues in all affected layers until healthy, bleeding tissue margins are reached (Fig. 1).5 Limb functionality and reconstruction should be considered during surgery; however, they should not determine the extent of debridement. For extremity NSTIs, factors such as the magnitude of systemic illness, the extent of debridement required and the likelihood of a functional extremity should be taken into account to determine if an amputation would be necessary.4 Additionally, it should be noted that planned amputation often results in better and faster recovery and a quicker return to function compared to futile attempts at limb salvage through multiple debridement surgeries, which may expose extensive neurovascular and bony structures.5

Delay in the identification and surgical management results in an increase in mortality and the number of surgeries needed to control the source.2 In 1998, Bilton et al.6,20 presented a series of 68 patients, and 21 of these were treated after 24h, resulting in a mortality of 38% and an average hospital stay of 46 days (IQ range 11–104). The other 47 patients were operated before 24h, resulting in a mortality of 4.2% and an average hospital stay of 28 days (IQ range 4–45) days. Wong et al.6,18 reported a series of 89 patients treated between 1997 and 2002, determining that the only independent factor associated with higher mortality was the delay of surgical treatment by more than 24h. However, in our series, we did not find any relationship between the time of surgery and complications, amputation or mortality.

Second-look surgery is recommended within 24–48h as it is believed to decrease mortality. It allows for a reassessment of the extent of the infection, perform new debridement and ensures the absence of progression. The average number of surgical procedures is 3–4 before coverage.2,5 More often than not, specific procedures are required to achieve the definitive coverage of soft tissue defects. Reconstructive options include primary closure, split-thickness skin grafts, full-thickness skin grafts, tissue expansion and pedicled or free flaps.5

In addition to surgery, early and aggressive antibiotic therapy is essential. While there are no randomized controlled trials on this matter, there is general agreement that broad-spectrum therapy must include a Meticilin-resistant Staphyloccoccus aureus active agent (vancomycin, daptomycin or linezolid) as well as an agent against gram-negative pathogens (piperacillin–tazobactam, ampicillin–sulbactam, cephalosporins or carbapenems). If necessary, an agent against anaerobic pathogens should be added, such as metronidazole or clindamycin. “Surgical Infection Society and Infectious Disease Society of America” recommends the use of clindamycin, since it decreases toxin production.2 Guidelines suggest maintaining antibiotic treatment until 48–72h after the disappearance of symptoms and fever.4

Adjunct therapies, such as hyperbaric oxygen (eliminates anaerobic pathogens and toxin production) or intravenous immunoglobulin have been investigated. These options are not routinely recommended, as there is no evidence of their utility. Nevertheless, they might be considered in extreme situations.4,7

ResultsHistorically, mortality rates have been reported as high as 50–60% in older series and 20–30% in more recent reviews. Currently, the most recent series report mortality rates of 7.6–16.6%.4 The associated morbidity is also quite high and is directly related to the extent of surgical debridement performed, amputation and the severity of the systemic illness. Early and intravenous antibiotic administration, along with prompt debridement, improve the prognosis.5

Five patients died in our series (22.73%), consistent with our literature research. All of them were taken to surgery before 24h and only three of them belonged to the high-risk group according to the LRINEC score. Table 6 summarizes the results of the published case series.

Case series previously reported.

| Author | Years | Places | Cases | Amputation | Number surgery | Surgical delay | Mean stay (days) | Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current research | 2016–2022 | Madrid | 22 | 13.64% | 3 | 8.25h | 22.51 | 22.73% |

| Pek8 | 2006–2012 | Singapur | 27 | – | – | 321.5h | 40.7 | 14.8% |

| Ferrer Lozano23 | 2008–2010 | Cuba | 11 | – | 6.5 | – | 37 | 9.09% |

| Kibadi10 | 2005–2009 | Francia | 17 | – | – | 64.8h | – | 11.7% |

| Ballesteros6 | 2001–2008 | BCN | 24 | 25% | 2.6 | 24h | 39.9 | 4.2% |

| Khanna24 | 1995–2007 | India | 118 | 20.3% | 2.3 | – | 34.3 | 15.2% |

| Rieger13 | 1999–2004 | Suiza | 16 | – | 5.2 | 72h | 46.6 | 18.7% |

| Ozalay11 | 1998–2003 | Turquía | 22 | 41% | 2 | – | 35.8 | 14% |

| Tiu9 | 1997–2002 | N. Zelanda | 48 | 10.41% | 4 | 21h | 31 | 29% |

| Hassel17 | 1994–2001 | Australia | 14 | 21.42% | – | – | – | 29% |

| Mulla12 | 1996–2000 | Florida | 257 | – | – | – | – | 18% |

Few studies on long-term outcomes have been reported. Light et al.5,21 found that survivors of NSTI have a higher mortality due to infectious causes. In our series there was only one death during follow-up and it was not related with infection.

There are currently no validated tools for the assessment of function in these patients. In the study of Pham et al.,22 30% of patients had at least mild to severe functional limitation. Hakkarainen et al.5 reported lower scores on physical and mental health scores in these patients. Additionally, they reported that 48% of patients were unable to return to their previous activity. In our study, 38.89% of patients returned to work, although 71.42% of them needed to adapt their activity, supporting the fact that, in addition to high mortality rates, NSTI have significant morbidity.

ConclusionsThe rapid and aggressive progression of NSTIs could endanger limbs or even life. Therefore, early suspicion and multidisciplinary treatment involving radical debridement, life support and antibiotic therapy are essential.

Various tools, such as the LRINEC score have been proposed to aid in the diagnosis of NSTIs. However, in our study, it accurately identifies only 72.72% (high or medium risk) of patients, indicating that low scores do not rule out the diagnosis. While some studies have reported an association between the LRINEC score and prognosis, we did not find any significant relationship. Similarly, we did not find a relationship between any risk factor and mortality, likely due to the sample size. Our hospital stays, outcomes and mortality rates align with our literature research, confirming high morbidity and mortality despite early and adequate treatment.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical considerationThis study has the approval of the Ethics and Research Committee of the Clínico San Carlos Hospital (23/813-E). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants or their relatives included in the study.

FundingThe authors declare that no funds, grants or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestNone.