There is a tendency for the aging population to fracture their hips. Our aim was to compare survival and functionality at one year, among elderly and very elderly patients with hip fracture.

Material and methodsA prospective cohort of patients included in the Institutional Registry of Elderly Patients with Hip Fracture between 2014 and 2017. We classified patients as elderly patients (EP) <65 and <85 years and very elderly patients (VEP) ≥85 years.

ResultsWe included 952 patients, 43% were EP and 57% were VEP. The proportion of women was 84% and 86% (P = .33) and with 2 or more points in the Charlson comorbidities index (28 and 31%, P = .36), respectively. The VEP were more dependent according to the Barthel score (34% and 62%, P < .01) and frailer according to the Edmonton score (30% and 61%, P < .01).

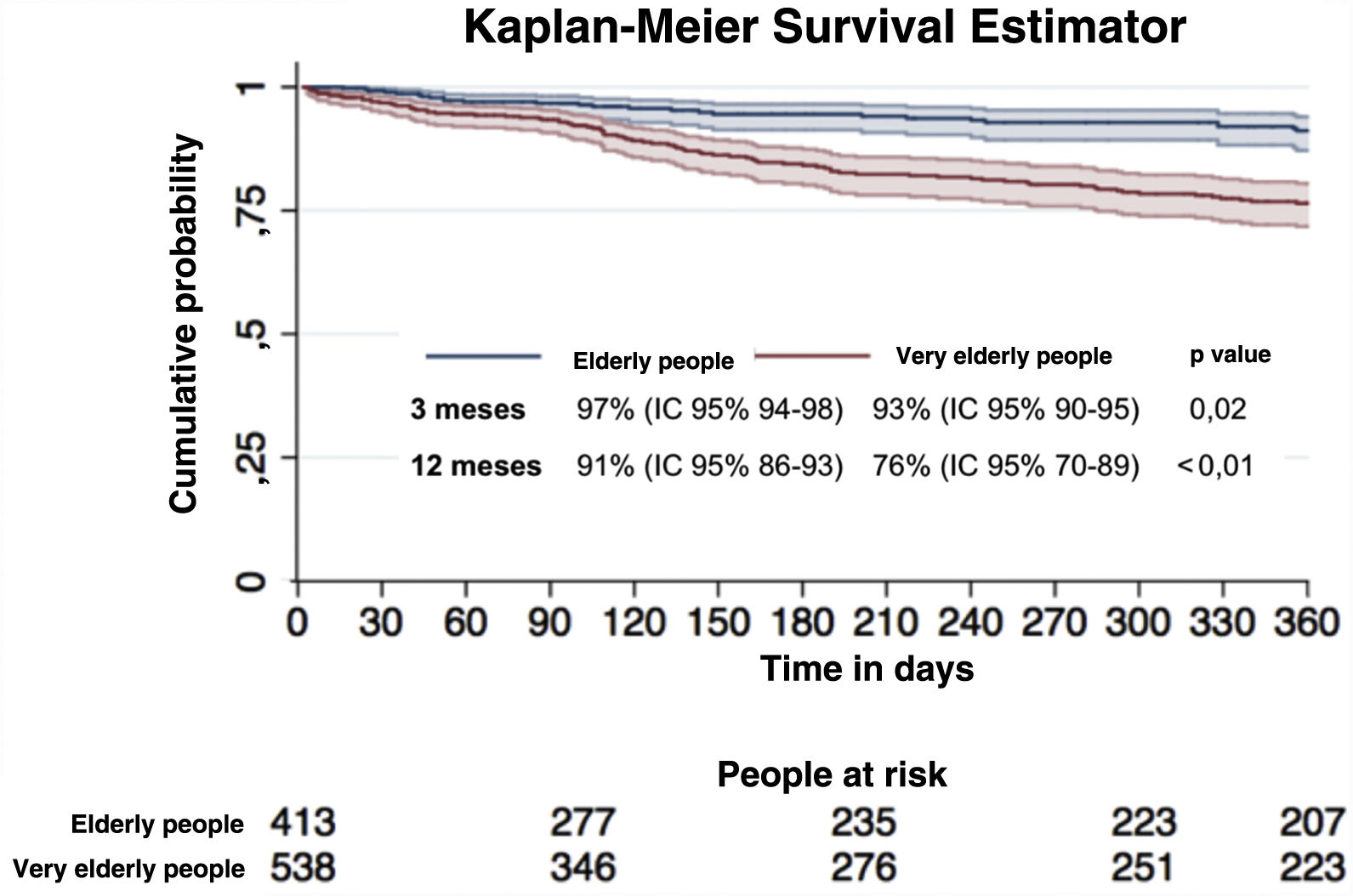

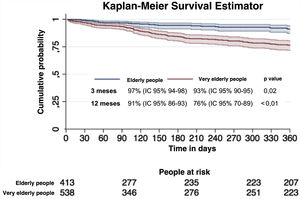

One-year survival was 91% (95% CI 86–93) in the EP and 76% (95% CI 70–89) in the VEP. In-hospital complications were more frequent in the VEP 12% (7% in the EP, P < .01).

Age is an independent risk factor for one-year survival (HR 2.11 (95% CI 1.36−3.29, P < .001).

ConclusionsAge is a risk factor for the VEP group survival despite fragility and comorbidities. Because of their vulnerability, an appropriate care plan should be considered for VEP.

Hay una tendencia al envejecimiento de la población que se fractura la cadera. Nuestro objetivo fue comparar la supervivencia y funcionalidad al año, entre ancianos y muy ancianos con fractura de cadera.

Material y métodosCohorte prospectiva de pacientes incluidos en el Registro Institucional de Ancianos con Fractura de Cadera entre los años 2014 y 2017. La población se clasificó: ancianos (A) entre los 65 y 85 años y pacientes muy ancianos (MA) mayor o igual a 85 años.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 952 pacientes, el 43% fueron A y el 57% fueron MA. De estos hubo 84% y 86% de mujeres (p = 0,33) y con dos o más puntos en el Índice de Comorbilidades de Charlson (28% y 31%, p = 0,36), respectivamente. Los MA fueron más dependientes por la puntuación de Barthel (34% y 62%, p < 0,01) y más frágiles (30% y 61%, p < 0,01).

La supervivencia a un año fue del 91% (IC 95% 86–93) en ancianos y del 76% (IC 95%: 70–89) en muy ancianos. Las complicaciones intrahospitalarias fueron más frecuentes en MA 12% (7% en A, p < 0,01).

La edad fue un factor de riesgo independiente para la supervivencia a un año (HR 2,11 IC 95% 1,36-3,29, p < 0,001).

ConclusiónLa edad es un factor de riesgo para la supervivencia del grupo MA a pesar de la fragilidad y comorbilidades. Debido a su vulnerabilidad, se debe considerar un plan de cuidado adecuado para los pacientes MA.

Between 2000 and 2050, the proportion of the population over 60 will double from 11% to 22% and the number of older people unable to look after themselves will increase by a factor of 4 in the developing countries. They will lose the ability to live independently because they will suffer from limited mobility, frailty or other physical or mental problems, requiring partial or total long-term care. Therapeutic management of chronic diseases and advances in surgical procedures are some of the reasons for longevity in the population.1,2

The annual incidence of hip fracture among people over 65 years of age is 646/100,000 inhabitants and its frequency is increasing due to population ageing (year-on-year growth rate of 1.4/100).3–6 Hip fracture occurs in an older, comorbid population with a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, polymedicated, frail and with a high probability of complications or flare-ups of chronic disease after the event.7–9 Studies focus on the evaluation of factors affecting the recovery of elderly people with hip fractures, but the majority focus on patients with a mean age of no more than 85 years.10

Very elderly patients are more prone to loss of function and institutionalisation after a hip fracture compared to elderly patients.1,8,11–14

Therefore, the objective of our study is to compare survival and function at one year, between the elderly and very elderly (aged 85 years and over) with hip fracture.15,16

Materials and methodsWe conducted a prospective cohort study at the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires (HIBA) between July 2014 and July 2017 with all patients included in the Institutional Registry of Elderly Patients with Hip Fracture (RIAFC).17

The HIBA is a prepaid facility that provides medical care to all beneficiaries through 2 high-complexity hospitals and 24 medical consultation buildings to more than 145,000 members located in Buenos Aires and the surrounding metropolitan area.18 The city of Buenos Aires is the capital of Argentina and has a population of 2,890,151. The city's data show the following socioeconomic status: 20.9% lower class, 51.4% middle class and 27.6% upper class. These affiliates are predominantly middle class.

From July 2014, the RIAFC started including patients and collecting primary data at the time of admission for fracture. All patients aged 65 years or older who presented with an acute hip fracture in HIBA headquarters were included. Pathological, subtrochanteric, periprosthetic, polytraumatic hip fractures were excluded.

The patients who met the selection criteria and agreed to participate underwent an oral consent process and a structured interview by a specially trained data collector. The interview targeted the patient, family and treating physician to gather all baseline clinical, geriatric and trauma characteristics of the patient. The clinical and geriatric characteristics of the patients evaluated were assessed with the Charlson comorbidities index (CCI), basic activities of daily living (BADL) functionality was assessed with the Barthel scale, instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) with the Lawton and Brody scale, and frailty with the Rockwood frailty scale.19–22 The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA)23 was used to assess nutritional risk. Trauma data were collected from the surgical area and the treatment team was contacted in the case of missing data or discrepancies. Data from hospitalisation to discharge were collected from electronic medical histories. In addition, in-hospital complications (infections, acute myocardial infarction, thromboembolic disease, atrial fibrillation, acute renal failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, stroke and loosening of prostheses) were collected.

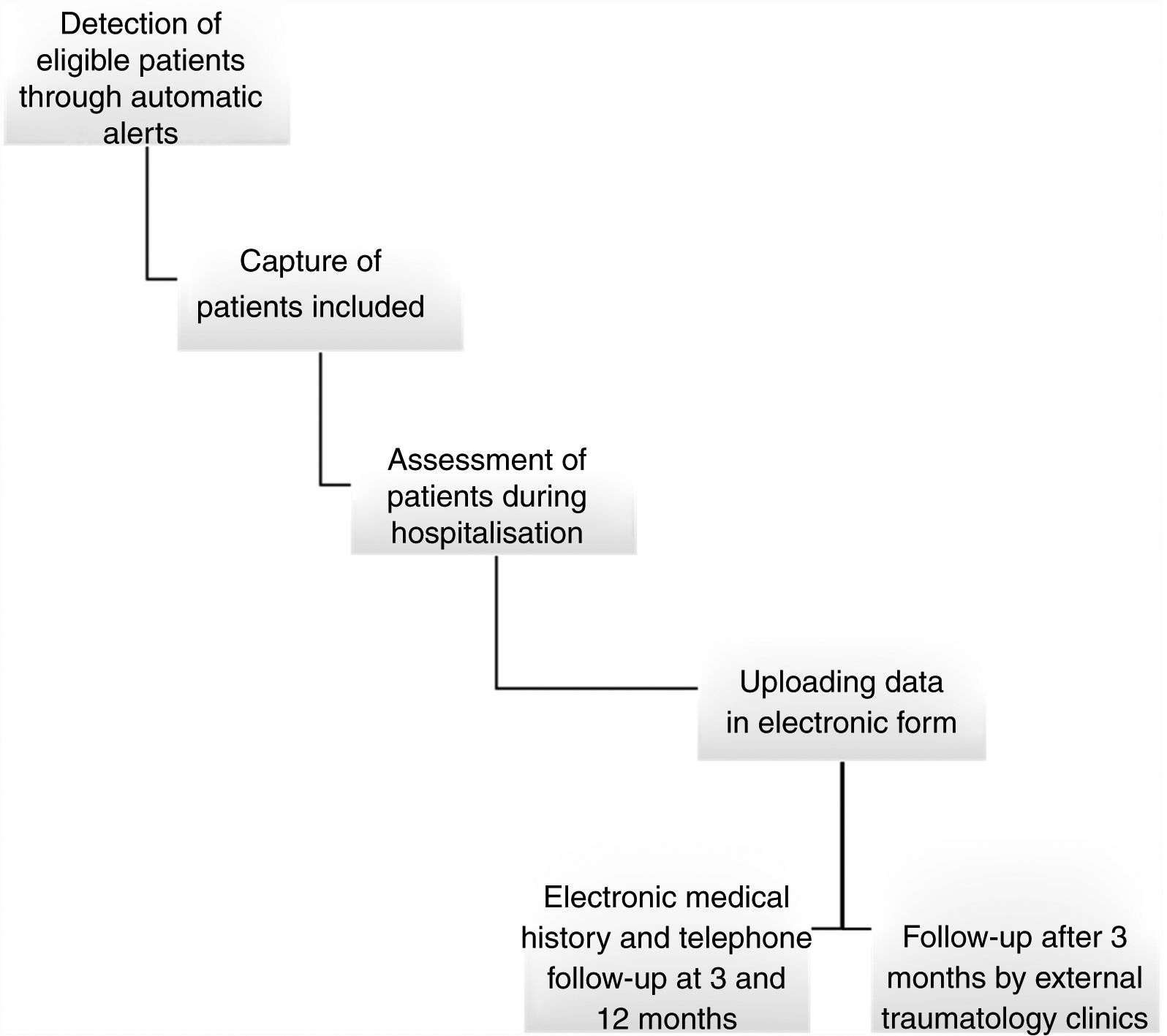

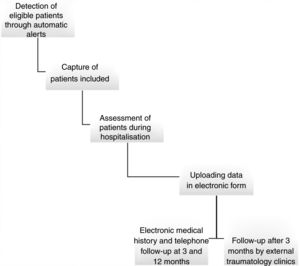

The data collector, for this study, followed up the patients, at 3 and 12 months, searching for information through their electronic medical history and contacted them by telephone (Fig. 1). The protocol for this study and their oral informed consent were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and the RIAFC is registered in clinicaltrials.gov with registration code NCT02279550. The authors have no conflict of interest.

For this study, the population was classified according to age into elderly (between 65 and under 85 years) and very elderly (85 years or over). Additionally, the following characteristics were dichotomised: frailty (Rockwood Frailty Scale ≥5), ICC ≥2, ASA (I-II and III-IV), malnutrition (MNA ≥12), functionality (Barthel BADL dependency <100; Lawton AIVD dependency <8).

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) according to observed distribution. Categorical variables will be presented with their absolute and relative value as proportions.

For the main hypothesis, the association of each exposure variable with survival by age group (elderly vs. very elderly) was tested using the Kaplan Meier estimator and Cox-Mantel test to compare survival curves. A Cox proportional risk model was constructed with significant dichotomous explanatory variables in the univariate analysis, to estimate the coefficient associated with each exposure variable and calculate the crude hazard ratio (HR), with its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We adjusted as confounding variables those that were statistically significant in the bivariate analysis or that the research group considered clinically relevant. The HR adjusted for confounding variables was estimated. A p < .05 was considered statistically significant. STATA 14 software, College Station, Texas, USA, was used for statistical analysis.

ResultsDuring the study period, 2440 automatic alerts were generated for potentially eligible patients: 1488 patients were excluded (1. 025 hip fracture events as a previous history or diagnostic error of fracture, 68 types of fracture excluded from this register, 24 patients were under 65 years of age, 277 patients were admitted to a centre that is ancillary to the central hospital where the evaluations are carried out, 92 patients were lost to assessment due to hospital discharge before evaluation for the study and only 2 patients refused to participate in the study), and 952 patients were included.

A total of 952 patients were included, of whom 413 were elderly and 539 were very elderly. The mean age was 78 (SD 4.9) for the elderly and 89 (SD 3.2) for the very elderly group. In both groups the majority of patients were female.

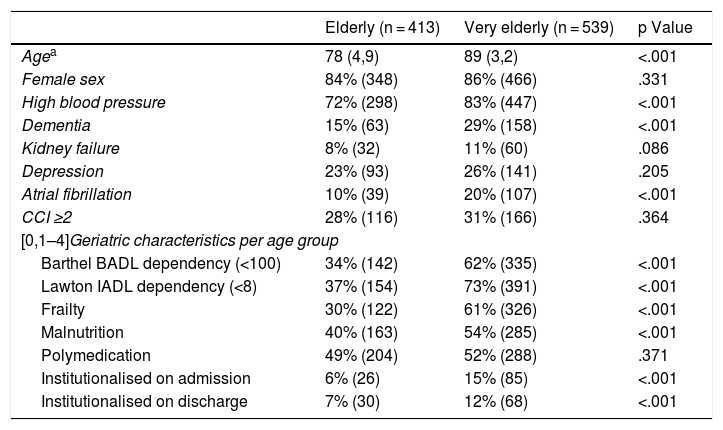

With regard to comorbidities, the elderly group presented less dementia, arterial hypertension and atrial fibrillation than the very elderly population. From the analysis of the geriatric variables we observed that the elderly population presented less dependence in both the basic and instrumental activities of daily living, less frailty and malnutrition than the very elderly group. No statistically significant differences were observed in polymedication between the two groups (Table 1).

General characteristics and geriatric aspects of the population according to age group.

| Elderly (n = 413) | Very elderly (n = 539) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agea | 78 (4,9) | 89 (3,2) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 84% (348) | 86% (466) | .331 |

| High blood pressure | 72% (298) | 83% (447) | <.001 |

| Dementia | 15% (63) | 29% (158) | <.001 |

| Kidney failure | 8% (32) | 11% (60) | .086 |

| Depression | 23% (93) | 26% (141) | .205 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 10% (39) | 20% (107) | <.001 |

| CCI ≥2 | 28% (116) | 31% (166) | .364 |

| [0,1–4]Geriatric characteristics per age group | |||

| Barthel BADL dependency (<100) | 34% (142) | 62% (335) | <.001 |

| Lawton IADL dependency (<8) | 37% (154) | 73% (391) | <.001 |

| Frailty | 30% (122) | 61% (326) | <.001 |

| Malnutrition | 40% (163) | 54% (285) | <.001 |

| Polymedication | 49% (204) | 52% (288) | .371 |

| Institutionalised on admission | 6% (26) | 15% (85) | <.001 |

| Institutionalised on discharge | 7% (30) | 12% (68) | <.001 |

BADL: basic activities of daily living; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index.

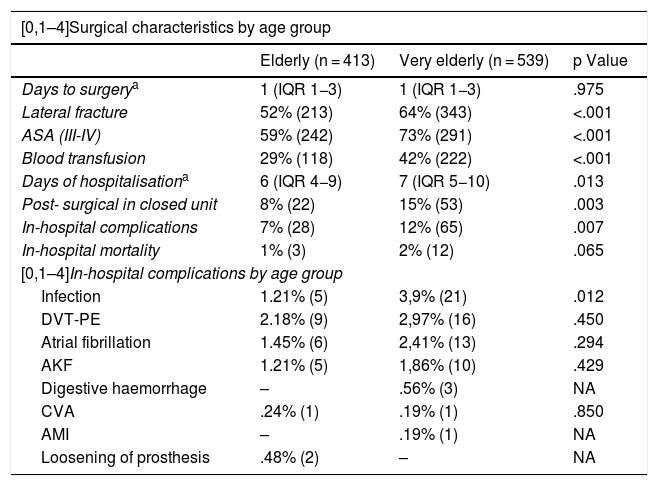

Surgical characteristics between both groups showed that the elderly group had fewer pertrochanteric fractures (52% vs. 64%; p < .01), lower ASA III-IV (59% vs. 73%; p .01), lower transfusion requirement (29% vs. 42%; p = .01) and shorter hospital stay (6 [IQR 4−9] vs. 7 [IQR 5−10]; p = .013) vs. the very elderly group. In-hospital complications were higher in the very elderly group (7% vs. 12%; p = .01).

There was no difference between the two groups in terms of the days from the patient's arrival at the emergency department until surgery (median of 1 day, IQR 1−3, and 1 day, IQR 1−3, in both age groups, P = .97).

The remaining characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of the surgical event and hospitalisation.

| [0,1–4]Surgical characteristics by age group | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Elderly (n = 413) | Very elderly (n = 539) | p Value | |

| Days to surgerya | 1 (IQR 1−3) | 1 (IQR 1−3) | .975 |

| Lateral fracture | 52% (213) | 64% (343) | <.001 |

| ASA (III-IV) | 59% (242) | 73% (291) | <.001 |

| Blood transfusion | 29% (118) | 42% (222) | <.001 |

| Days of hospitalisationa | 6 (IQR 4−9) | 7 (IQR 5−10) | .013 |

| Post- surgical in closed unit | 8% (22) | 15% (53) | .003 |

| In-hospital complications | 7% (28) | 12% (65) | .007 |

| In-hospital mortality | 1% (3) | 2% (12) | .065 |

| [0,1–4]In-hospital complications by age group | |||

| Infection | 1.21% (5) | 3,9% (21) | .012 |

| DVT-PE | 2.18% (9) | 2,97% (16) | .450 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.45% (6) | 2,41% (13) | .294 |

| AKF | 1.21% (5) | 1,86% (10) | .429 |

| Digestive haemorrhage | – | .56% (3) | NA |

| CVA | .24% (1) | .19% (1) | .850 |

| AMI | – | .19% (1) | NA |

| Loosening of prosthesis | .48% (2) | – | NA |

All the variables are expressed in % (n), except for those indicated as median (IQR).

CVA: cerebrovascular accident; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; BADL: basic activities of daily living; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living; AMI: acute myocardial infarction; AKF: acute kidney failure; IQR: interquartile range; DVT-PE: Deep vein thrombosis-pulmonary embolism.

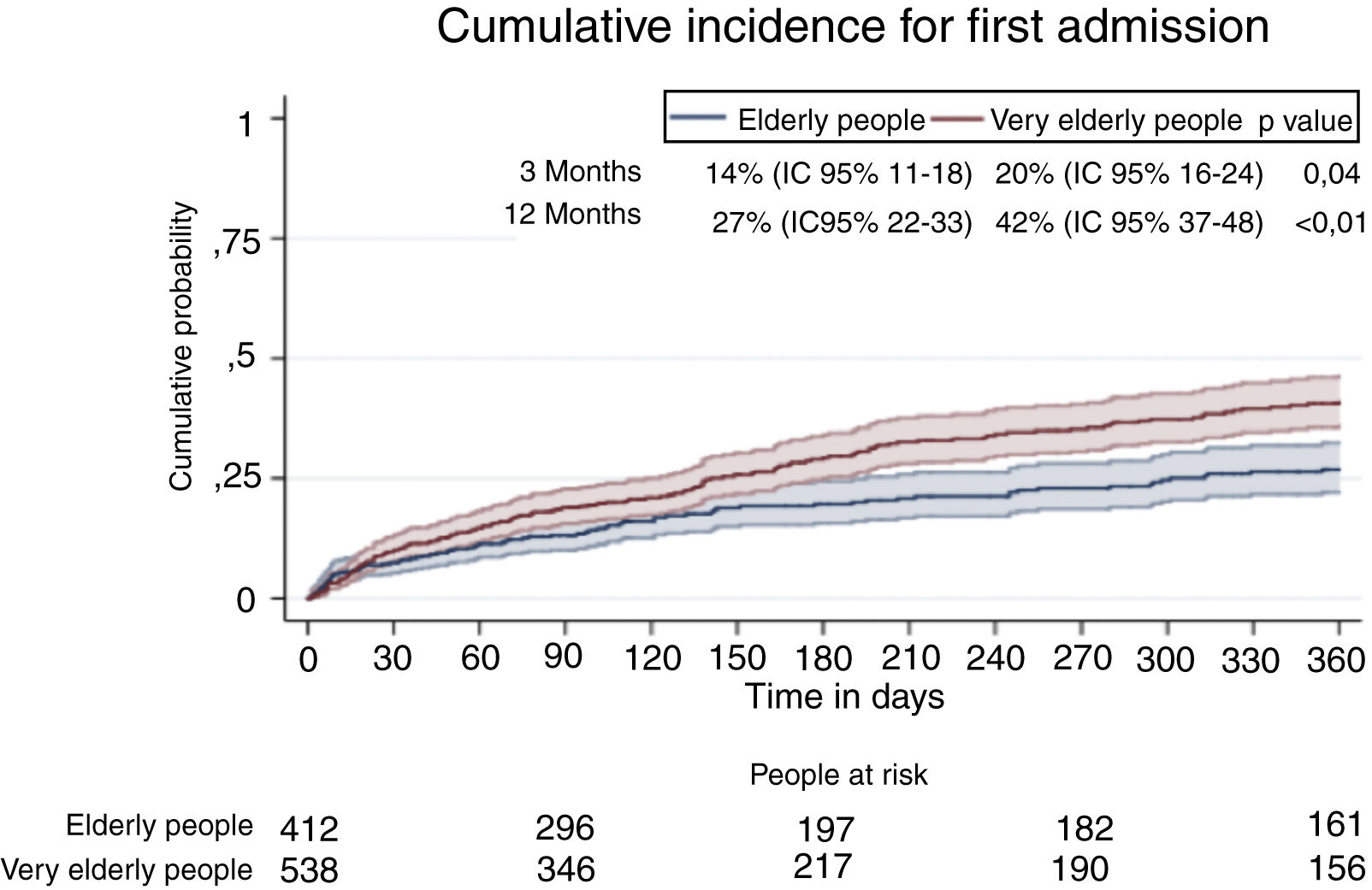

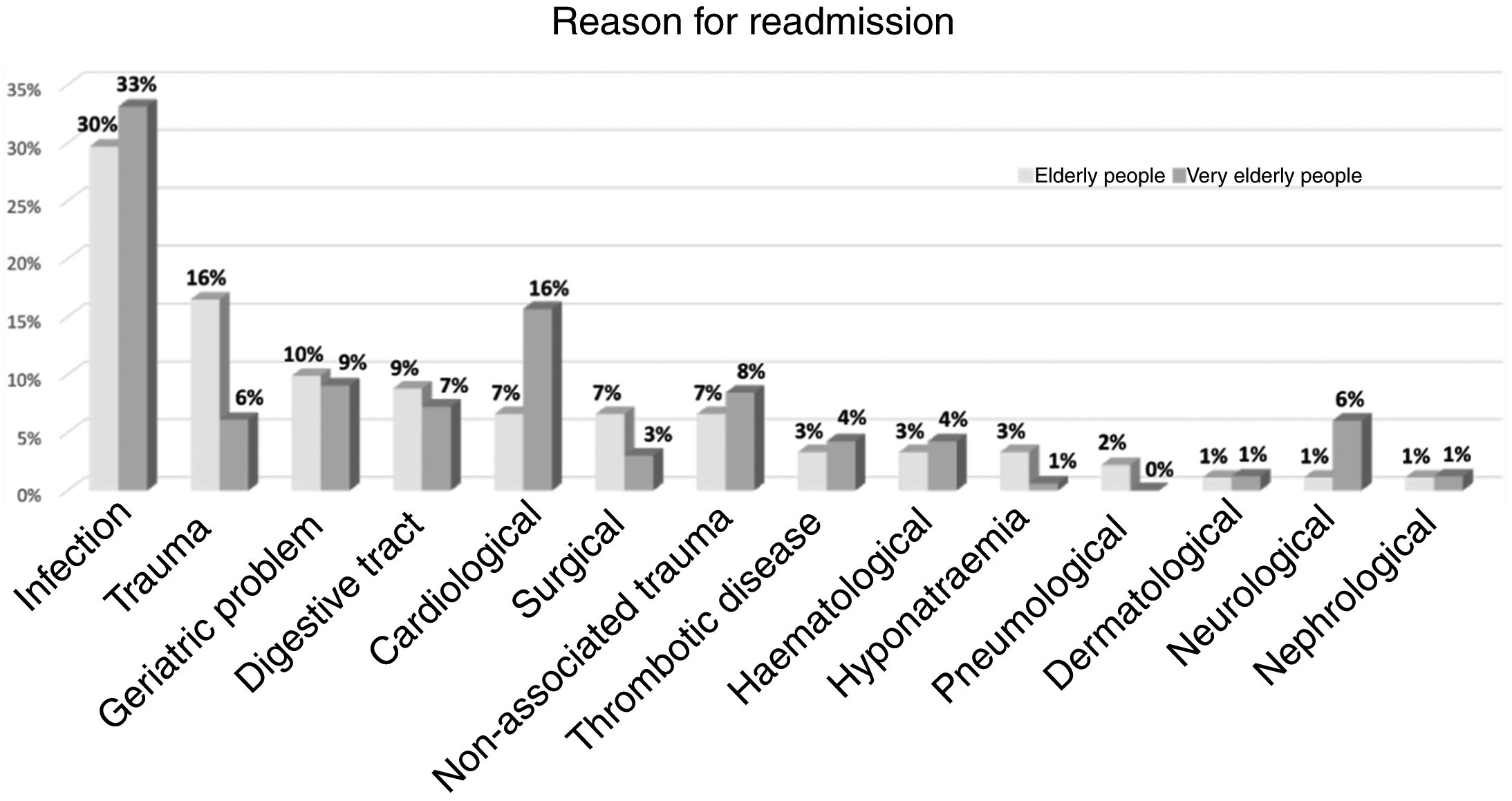

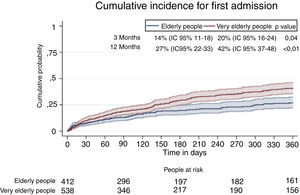

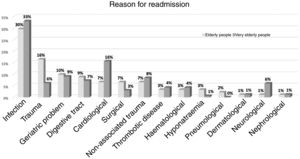

Hospital readmissions in the elderly and very elderly group at 3 months were 14% (95% CI, 11–18) and 20% (95% CI, 16–24), respectively, and at 12 months 27% (95% CI, 22–33) and 42% (95% CI, 37–48) in the elderly and very elderly group respectively (Fig. 2). The reasons for rehospitalisation are described in Fig. 3.

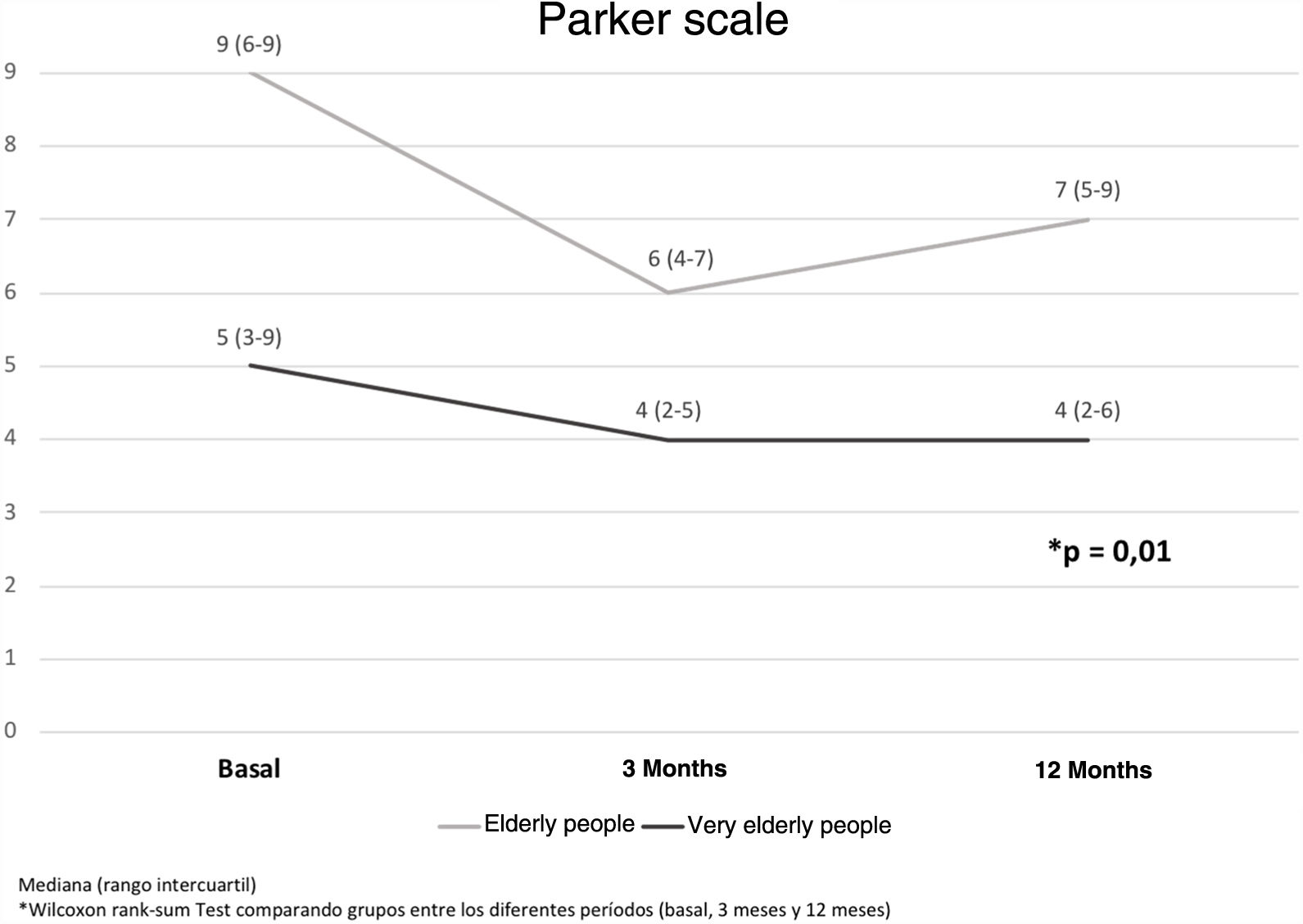

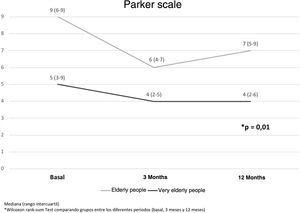

With regard to functionality, it can be seen that the elderly started from a higher Parker scale than the younger patients. At the end of the follow-up, none of the groups recovered their baseline, although the very old group continued at a lower level than the initial level at both 3 months and 12 months (Fig. 4).

Survival among the elderly and very elderly patients after suffering a hip fracture at 3 months was 97% and 93%, respectively (p .02) and at 12 months 91% and 76% (p = .001), respectively. The survival curves of both groups are shown in Fig. 5.

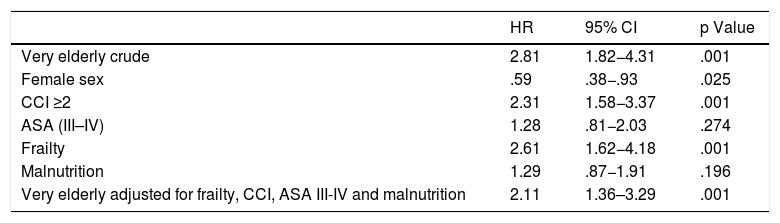

The HR of mortality of the very elderly group with respect to the elderly group was 2.11 (95% CI, 1.36–4.31 p < .01) adjusted for frailty, CCI, ASA and malnutrition (Table 3).

Risk of mortality associated with belonging to the very elderly group.

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very elderly crude | 2.81 | 1.82−4.31 | .001 |

| Female sex | .59 | .38−.93 | .025 |

| CCI ≥2 | 2.31 | 1.58−3.37 | .001 |

| ASA (III–IV) | 1.28 | .81−2.03 | .274 |

| Frailty | 2.61 | 1.62−4.18 | .001 |

| Malnutrition | 1.29 | .87−1.91 | .196 |

| Very elderly adjusted for frailty, CCI, ASA III-IV and malnutrition | 2.11 | 1.36–3.29 | .001 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; CCI: Charlson comorbidity index.

In a subgroup analysis of the very elderly population, factors were found that could explain the phenomenon of the mortality associated with this particular group. Of these factors, the most important identified in this study were frailty and CHF ≥ 2 (HR 2.30, 95% CI, 1.39–3.81, p < .001 and HR 2.32, 95% CI, 1.56–3.45, p < .001, respectively).

DiscussionAccording to the results of the study, the very elderly group had shorter survival and more impaired functionality than the elderly group.

In the literature, the mortality of very elderly patients at 12 months is reported to be between 10% and 36%, these results being consistent with ours.24–34

Our very elderly population is frail, with functional deterioration and malnutrition, with an increased risk of worse clinical outcome from a stressful event such as hip fracture.35 Despite these factors that influence mortality, age proved to be an independent factor for mortality at one year. We included demented elderly, chronic renal and oncological patients in our cohort, these comorbidities being frequently associated with patient mortality and excluded in other publications.36

Intrahospital complications were greater in the very elderly group, who mainly presented infections, thromboembolic disease and atrial fibrillation. These data are similar to other papers publishing that the main post-surgical complications are respiratory infections and cardiovascular complications.28 We do not systematically assess for delirium during hospitalisation of patients with hip fracture; we are in the process of implementing this information in the RIAFC.

Functionality, both baseline and post hip fracture, was better in the elderly group. It was observed that at 3 months after surgery both groups deteriorated from baseline. At 12 months, the elderly group partially recovered their functionality, while the very elderly group maintained the deterioration in functionality from 3 months to one year without achieving the same recovery as the elderly group. We think that this is related to the frail status of the very elderly patients before surgery and their low capacity for rehabilitation after the fracture.32 However, the baseline status of this group was more impaired when they fractured their hips than the elderly group and their being able to maintain a stable functional state could be an achievement and a potential therapeutic goal.

In the very elderly group, the median hospital stay is one day less compared to the elderly group. This difference is statistically significant, although we did not consider it from a clinical point of view. This latter concept is related to prompt surgery from their arrival at the hospital and to the same care that all patients with hip fracture receive, despite their age. We believe that we achieve international standards by having a care model in the hospital under the charge of traumatology specialists and geriatric clinical physicians who work interdisciplinarily forming a virtual orthogeriatric unit. Although this study was conducted in a single high-complexity centre, it is a referral hospital, where referrals are received from all over the country.

The hospital stay for the very elderly group is lower than that reported internationally (10–25 days).29,37,38 This difference could be to do with the fact that all patients who are discharged from hospital continue their transitional care with doctors and kinesiologists at home.

ConclusionsThe findings of our study attempt to demonstrate that belonging to the very elderly group, regardless of other poor prognostic factors such as frailty and comorbidities, is associated with higher morbidity and mortality. This information provides knowledge for the patient, his or her family members and the treating medical team. Thus, we can establish a more precise prognosis, determine therapeutic adequacy and expectation for recovery for the very elderly patient.

It would be useful to evaluate whether the very elderly patient group requires medical care tailored to their frailty and comorbidities to improve their post-hip fracture recovery.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence ii.

FundingThis research study has received no specific grants from agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors. It was funded by the HIBA Medical Clinic Service, Argentina.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Benchimol JA, Elizondo CM, Giunta DH, Schapira MC, Pollan JA, Barla JD, et al. Supervivencia y funcionalidad en ancianos mayores de 85 años con fractura de cadera. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:265–271.