Descriptive anatomical study of the different surgical approaches to the talus with photographic documentation using a 3-dimensional technique. The objective of this study is to evaluate macroscopic reference points, anatomical planes, structures at risk, field of visualization and possible applicability of each approach to help decision-making at the time of surgical planning in the event of a fracture of the talus. Eighteen fresh specimens and two specimens injected with black latex through the popliteal artery were dissected, performing each surgical approach twice with photographic documentation.

Estudio anatómico descriptivo de las diferentes vías de abordaje de astrágalo, con documentación fotográfica, utilizando técnica en 3 dimensiones. Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar puntos de referencia macroscópicos, planos anatómicos, estructuras en riesgo, campo de visualización y posible aplicabilidad de cada vía de abordaje para ayudar a la toma de decisiones en el momento de la planificación quirúrgica ante una fractura de astrágalo. Dieciocho especímenes frescos y 2 inyecciones con látex en la arteria poplítea fueron estudiados realizando 2 veces cada vía de abordaje con documentación fotográfica. Este estudio propone la necesidad de realizar una correcta planificación prequirúrgica para elegir la mejor vía de abordaje en cada caso y la importancia de realizar, en la gran mayoría de casos, la vía combinada para conseguir una reducción correcta.

Fractures of the talus are the second most common fracture of the tarsus, following those of the calcaneus. They are, however, infrequent, due to the bony protection offered by the tibiofibular overlap with its ligament structures.

The peculiarity of the talus is that up to 70% of it is enveloped in articular cartilage, there are no tendinosous insertions and vascularity is poor, mainly coming from the branches of the posterior tibial nerve, the perforating peroneal artery and the anterior tibial nerve.1

Although lesions are not very common, they are considered serious due to the complexity of surgical treatment and subsequent sequelae. Exhaustive pre-surgical planning is therefore required for each case to decide the best access route for optimum visualization and to achieve the most anatomically possible reduction.

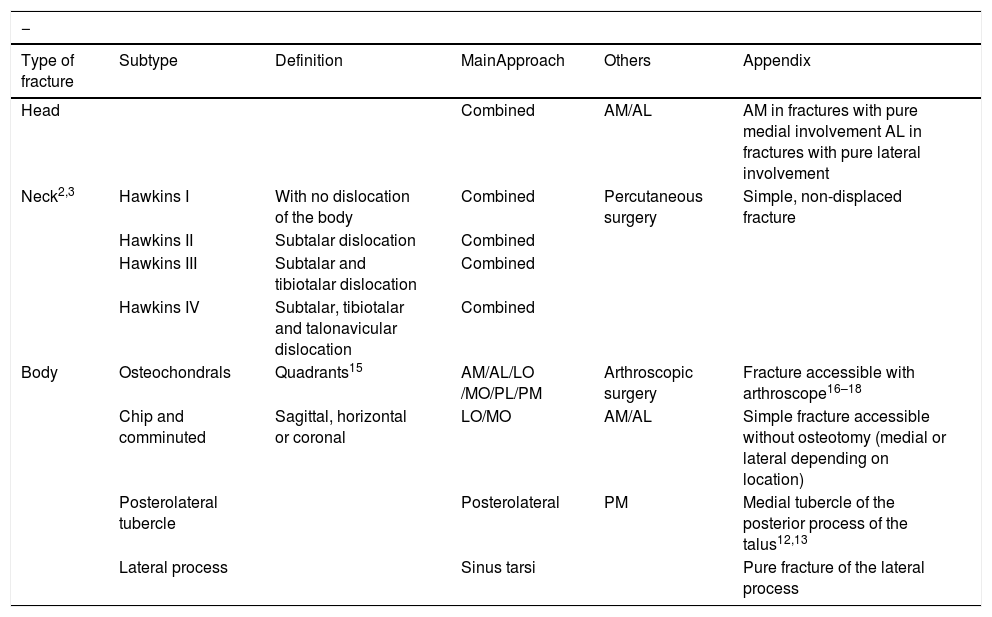

Historically great importance has been attached to the type of fracture (Hawkins classification modified by Canale),2,3 with detailed awareness of access routes being secondary, even though they are essential for any surgeon when performing surgery on these fractures (Table 1).

Summary of talus fracture classification.

| − | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of fracture | Subtype | Definition | MainApproach | Others | Appendix |

| Head | Combined | AM/AL | AM in fractures with pure medial involvement AL in fractures with pure lateral involvement | ||

| Neck2,3 | Hawkins I | With no dislocation of the body | Combined | Percutaneous surgery | Simple, non-displaced fracture |

| Hawkins II | Subtalar dislocation | Combined | |||

| Hawkins III | Subtalar and tibiotalar dislocation | Combined | |||

| Hawkins IV | Subtalar, tibiotalar and talonavicular dislocation | Combined | |||

| Body | Osteochondrals | Quadrants15 | AM/AL/LO /MO/PL/PM | Arthroscopic surgery | Fracture accessible with arthroscope16–18 |

| Chip and comminuted | Sagittal, horizontal or coronal | LO/MO | AM/AL | Simple fracture accessible without osteotomy (medial or lateral depending on location) | |

| Posterolateral tubercle | Posterolateral | PM | Medial tubercle of the posterior process of the talus12,13 | ||

| Lateral process | Sinus tarsi | Pure fracture of the lateral process | |||

AM: anteromedial; AL: anterolateral; LO: lateral osteotomy; MO: medial osteotomy; PM: posteromedial; PL: posterolateral.

The purpose of this study was to analyse the different routes with points of reference, risks and fields of view to aid decision-making when addressing each type of talus fracture.4

Material and methodsAn anatomical descriptive study of 10 access routes for talar fractures (anterolateral, anteromedial, combined anterior, lateral process, extended anterolateral, tibial malleolar osteotomy, fibular malleolar osteotomy, bilateral osteotomy, posteromedial and posterolateral).

Anatomic dissections were performed on 18 fresh lower limbs, obtained from our institution’s cadaver donation programme. Two injections with black latex were also made through the popliteal artery to evaluate talar vascularisation.

Photographs were taken with a Nikon 810D reflex camera, using a Nikon AF-S VR Micro-Nikkor 105 mm f/2.8G IF-ED lens. The specimens were photographed at f/20 with a sensitivity of 64 ISO. The specimens were illuminated with 4 Godox Wistro Pocket Flash AD200 flashes in TTL mode, providing 3 dimensional observation of the specimen, defining the volume of the object and providing a more realistic image, with greater detail to each route performed.

Each approach was performed on 2 anatomical specimens, assessing macroscopic points of reference, anatomical planes, structures at risk, field of view and possible applicability of each route according to fracture type.

ResultsAnterolateral routeIndicationsTalar body fractures. Osteochondral fractures of the anterolateral dome (quadrants 2 and 3)15–18 and comminuted fractures or from chipping of the lateral wall most anterior to the talar body.

Fractures of the head and neck of the talus with pure lateral fracture line.

Field of view. Anterolateral talar dome, anterolateral wall of the lateral body, head and neck.

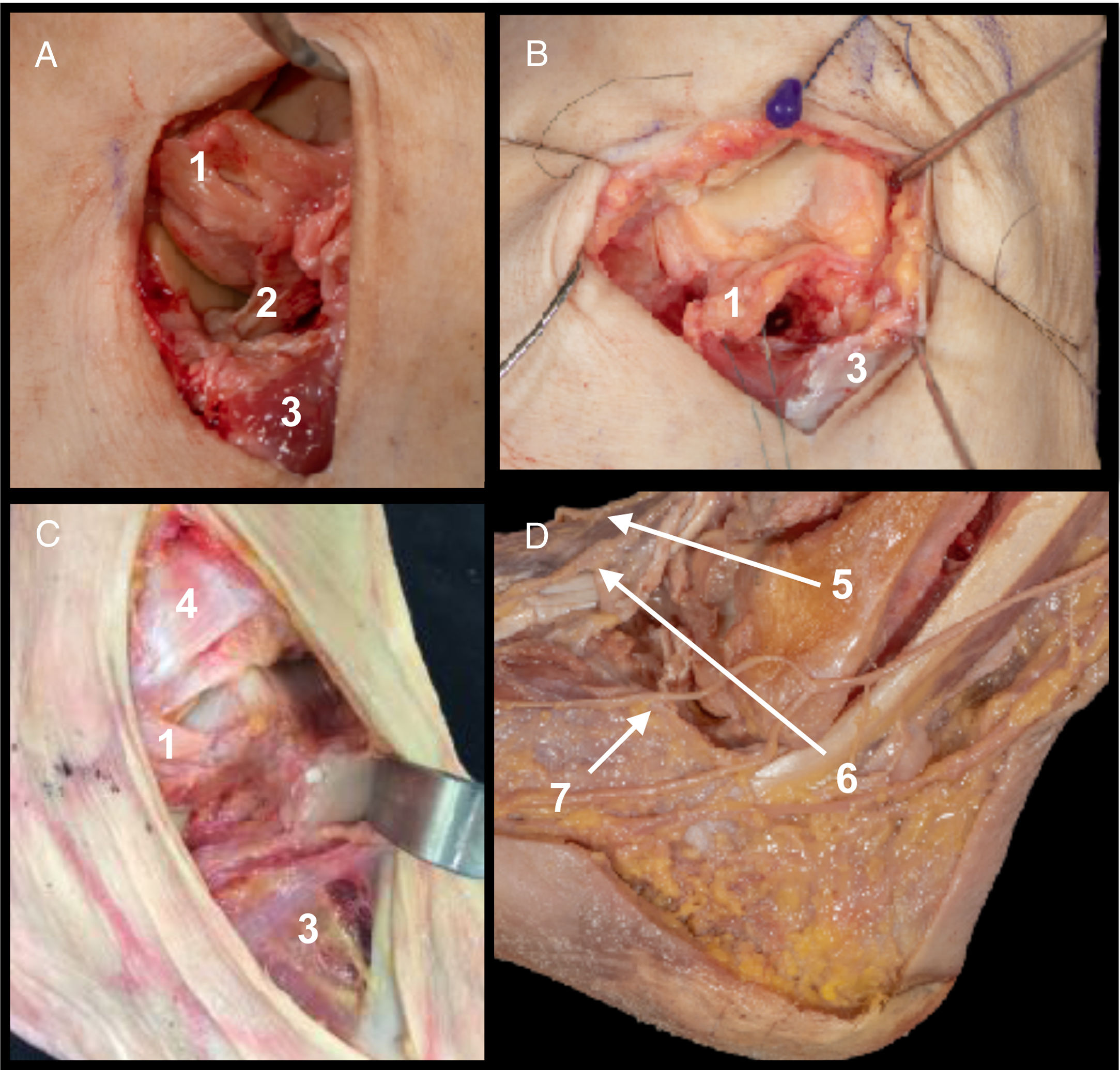

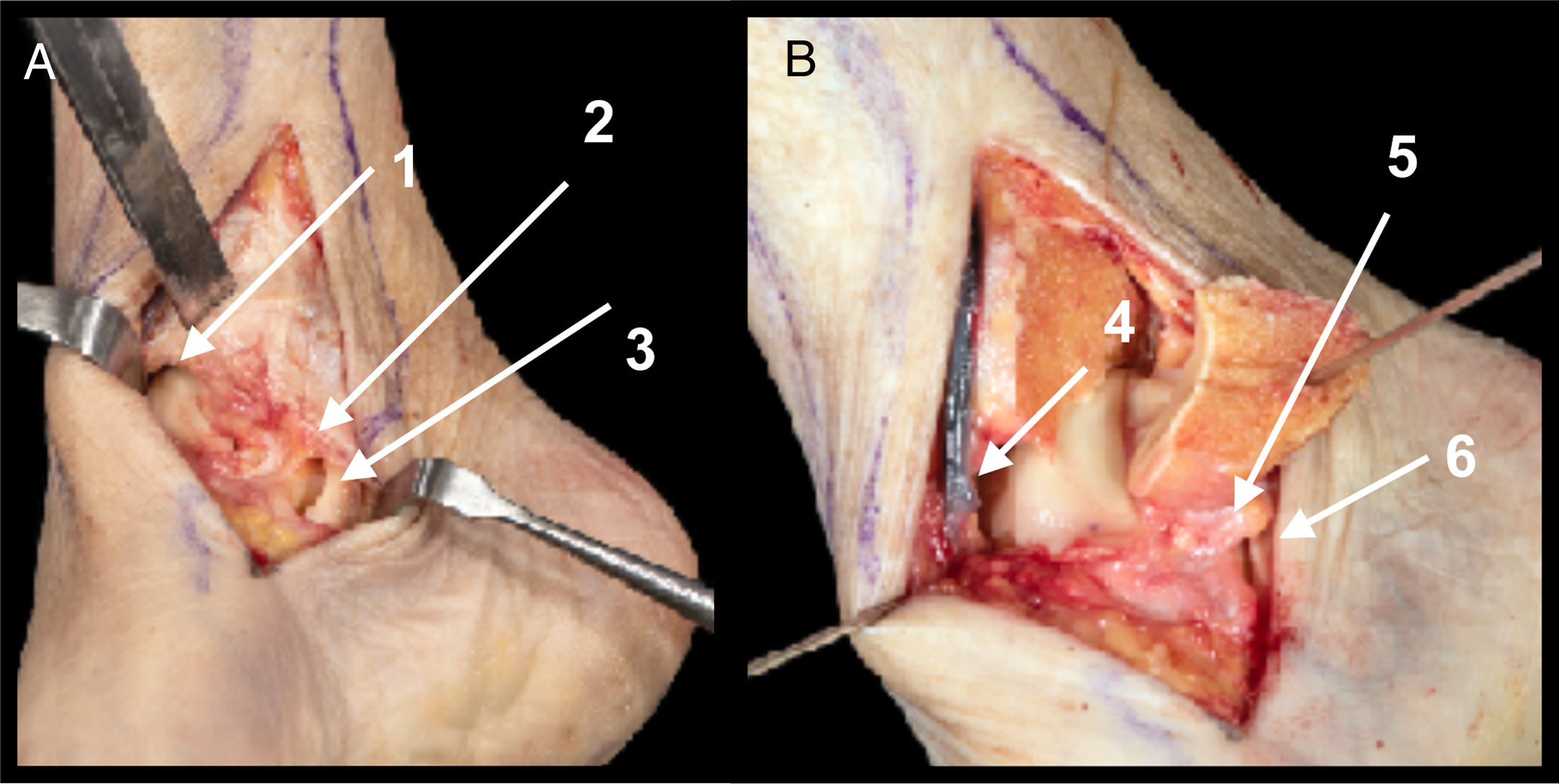

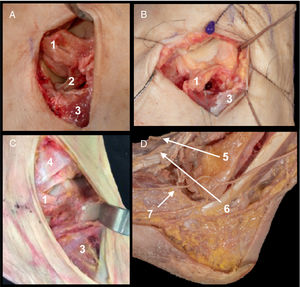

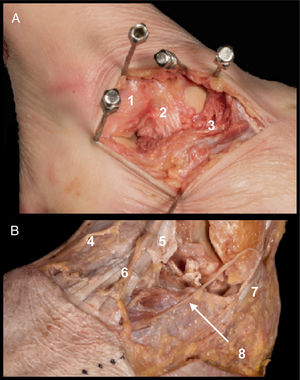

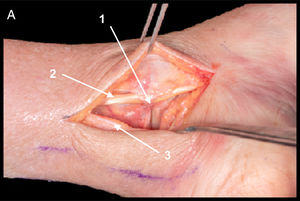

ApproachReferences. Anterior section of the peroneal malleolus to the calcaneocuboid joint, following the direction of the diaphysis of the fourth metatarsal. Approximately 6 cm of extension. Anatomical details. Extraction of tarsal fatty tissue-opening of the lateral talocalcaneal ligament and of the interosseous ligament (Fig. 1A). Transversal sectioning of the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL)5 (sectioning of the ATFL would only be necessary in fractures of the talar body, and is not essential in fractures of the neck or head. Sectioning of the ligament may be transversal in the middle third or in the peroneal insertion, and in both cases suture or posterior reinsertion would be required [Fig. 1B]). Proximal removal of the extensor digitorum brevis (EDB) (proximal removal of the EDB provides access to the region of the head and neck, and in a talar body fracture this may be avoided [Fig. 1C]).

A. Anterior tibiotalar ligament (1) and interosseous talocalcaneal ligament (2). Insertion of EDB (3).

B. Field of view of the neck with sectioning of ATFL (1) and without removal of EDB (3).

C. Field of view of head with opening of EDB (3) without removal of anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (4).

D. Structures at risk. Medial dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial fibular nerve (5), intermediate dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial fibular nerve (6) and dorsolateral cutaneous branch of the sural nerve (7).

Structures at risk. Intermediate dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial fibular nerve and lateral dorsal cutaneous branch of the sural nerve. Sinus tarsi artery7–9 (it should be taken into consideration that due to the high energy required to cause these fractures arterial irrigation of the talus may be damaged) (Fig. 1D).

Anteromedial routeIndicationsTalar body fractures. Osteochondrals of the anteromedial dome (quadrants 1 and 2)15–18 and comminuted fractures or from chipping of the medial wall most anterior to the talar body (in more posterior fractures of the talar body medial osteotomy of the tibial malleolus is recommended).

Fracture of the head and neck with pure medial line fracture.

Field of view. Anteromedial dome, medial wall of the medial body, head and neck (Fig. 2D).

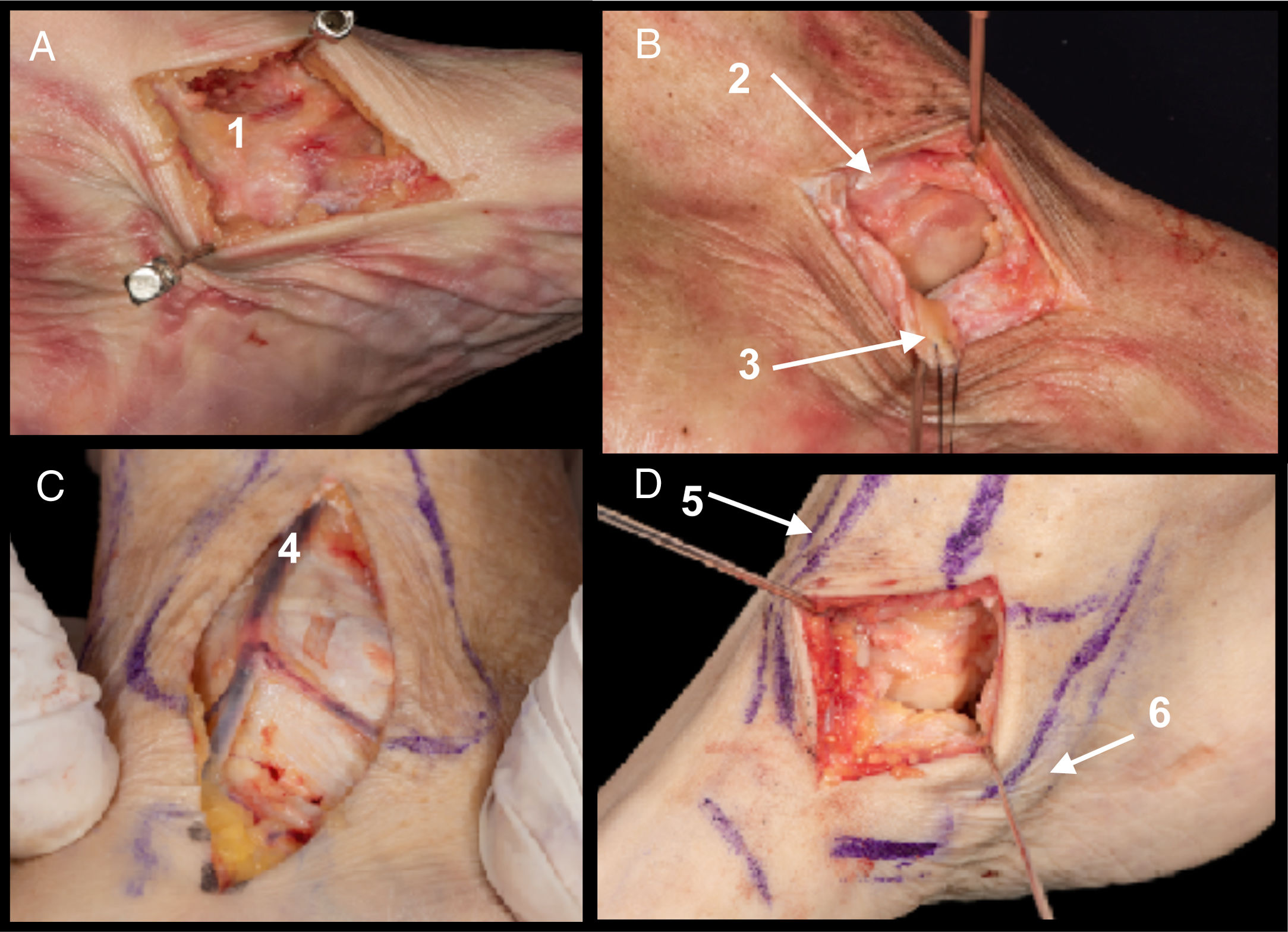

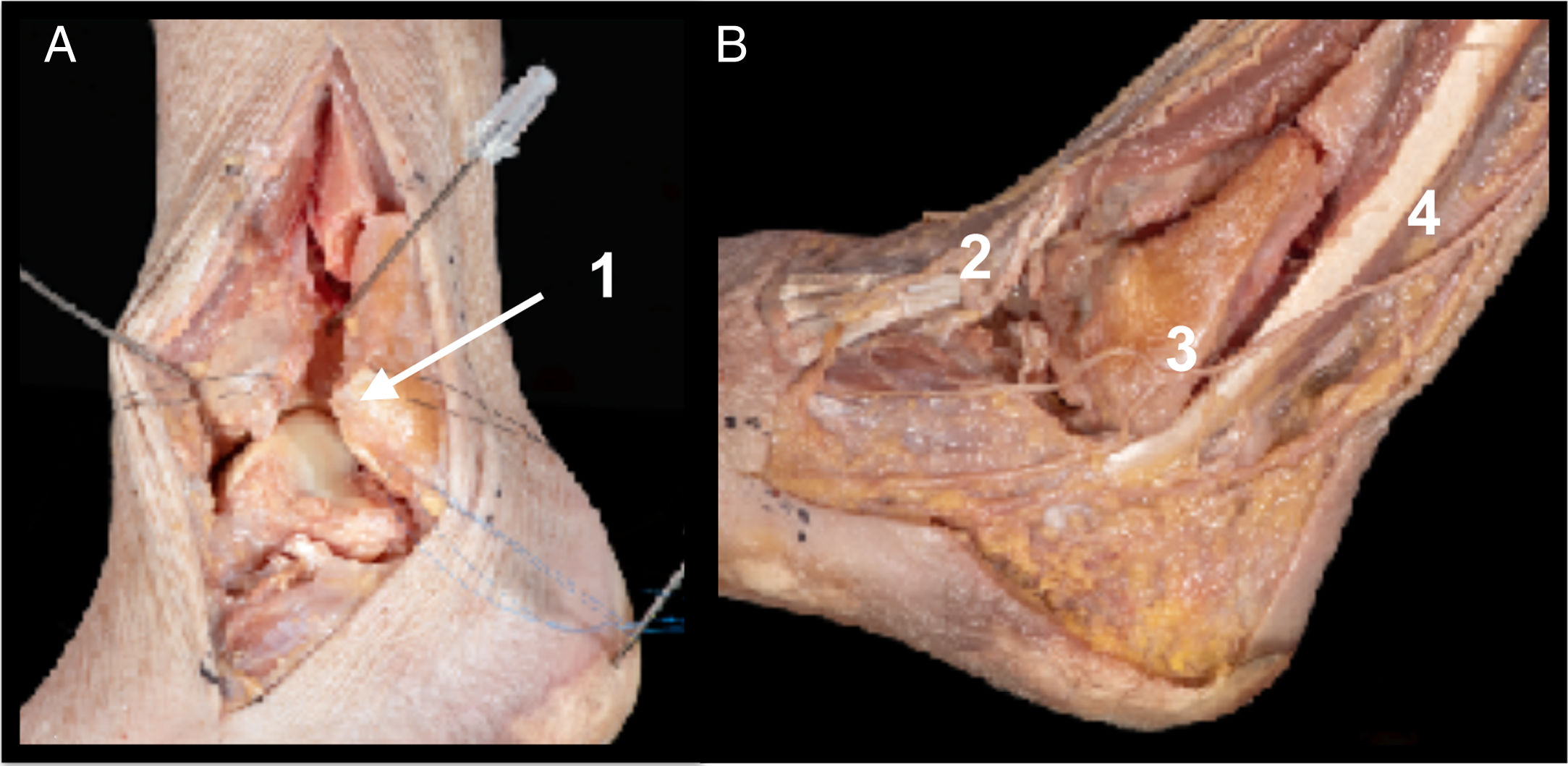

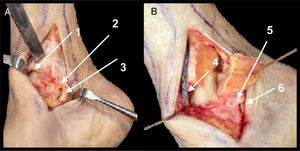

A. Superficial deltoid ligament (1).

B. Opening of the deep deltoid ligament. Anterior tibiotalar fascicle (2) and tibionavicular fascicle (3).

C. Structures at risk. Internal saphenous nerve and great saphenous vein (4).

D. Field of view after opening of deep deltoid fascicles. Anterior tibial route (5) and posterior tibial route (6).

References. From the anterior end of the malleolus to the talonavicular joint in the direction of the diaphysis of the first metatarsal, between the anterior tibial tendon and the posterior tibial tendon. Approximately 5 cm in length.

Anatomical details. Longitudinal opening in keeping with the direction of the incision of the superficial deltoid ligament (Fig. 2A). Opening of the deep deltoid ligament (tibionavicular and anterior tibiotalar fascicle) (Fig. 2B) (the opening of the more posterior deep deltoid fascicles is not recommended) [posterior tibiotalar and tibiocalcaneal], or the plantar calcaneonavicular ligament, since this is the region where vascularisation occurs through the branches of the posterior tibial artery7–9). Opening of the dorsal talonavicular artery.5

Structures at risk. Greater saphenous vein and internal saphenous nerve (Fig. 2C), deltoid artery and tarsal canal artery (branches of the posterior tibial artery with high variability of origin) and medial talar artery and recurrent arteries (branches of the dorsalis pedis artery).

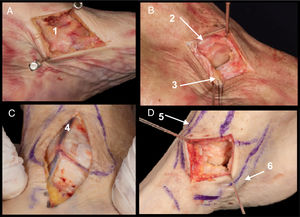

Pure lateral route or through sinus tarsiIndicationsLateral process fractures (“snowboard” fracture) and control of subtalar joint.

Field of view. Lateral process of the talus and posterior subtalar joint (Fig. 3C).

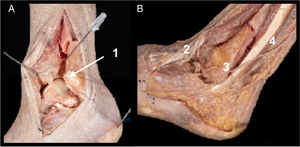

A. Field of view of the lateral process and posterior subtalar joint (1). Extensor retinaculum (2).

B. Pure lateral route where the ATFL is exposed with superior and inferior fascicle (3) and the talus and posterior subtalar lateral process (4).

C. Presentation with anatomical variant in which the inferior fascicle of the ATFL is jointed with fibres of the PCL above the lateral process of the talus (5). Sectioning of the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament. (6).

References. From 1 cm posterior to the peroneal malleolus up to 2 cm anterior probing the lateral process of the talus, superior to the peroneals and parallel to the ground. Approximatey 3 cm in length.

Anatomical details. Sectioning of the interosseous talocalcaneal ligament. Opening of the joint capsule between the ATFL and the peroneocalcaneal ligament (PCL) (Fig. 3A).5 (anatomical variant [Fig. 3B]. On occasions anatomical variants have been found in which the inferior fascicle of the ATFL is joined to the fibres of the PCL above the lateral process of the talus, and therefore on these occasions it would be necessary to section this fascicle in order to view the lateral process).6

Structures at risk. Peroneal tendons, ATFL and PCL.

Combined anterior route (combining anteromedial and anterolateral routes)IndicationsFractures of the head and neck. Main route for this type of fractures.

Fractures of the body: comminuted fractures or chip fractures of the anterior body.

Field of view. Head, neck, body and anterior talar dome. Improves visualisation and fracture control, facilitating reduction and synthesis.

ApproachThe same references, anatomical planes and risks as described previously for the anteromedial and anterolateral routes, leaving a minimum distance, between both approaches of 5 cm to prevent cutaneous necrosis.10

Extended anterolateral route (modified Ollier route)IndicationsFracture of the head with proximal extension to the neck or the body (with involvement or non-involvement of the lateral process). This route could be combined with the AM route to improve control of the fracture.

Field of view. Head, neck, lateral process and inframalleolar body.

ApproachReferences. Two centimeters posterior to the border of the fibula up to the talonavicular joint. Curved incision of 8−10 cm in length.

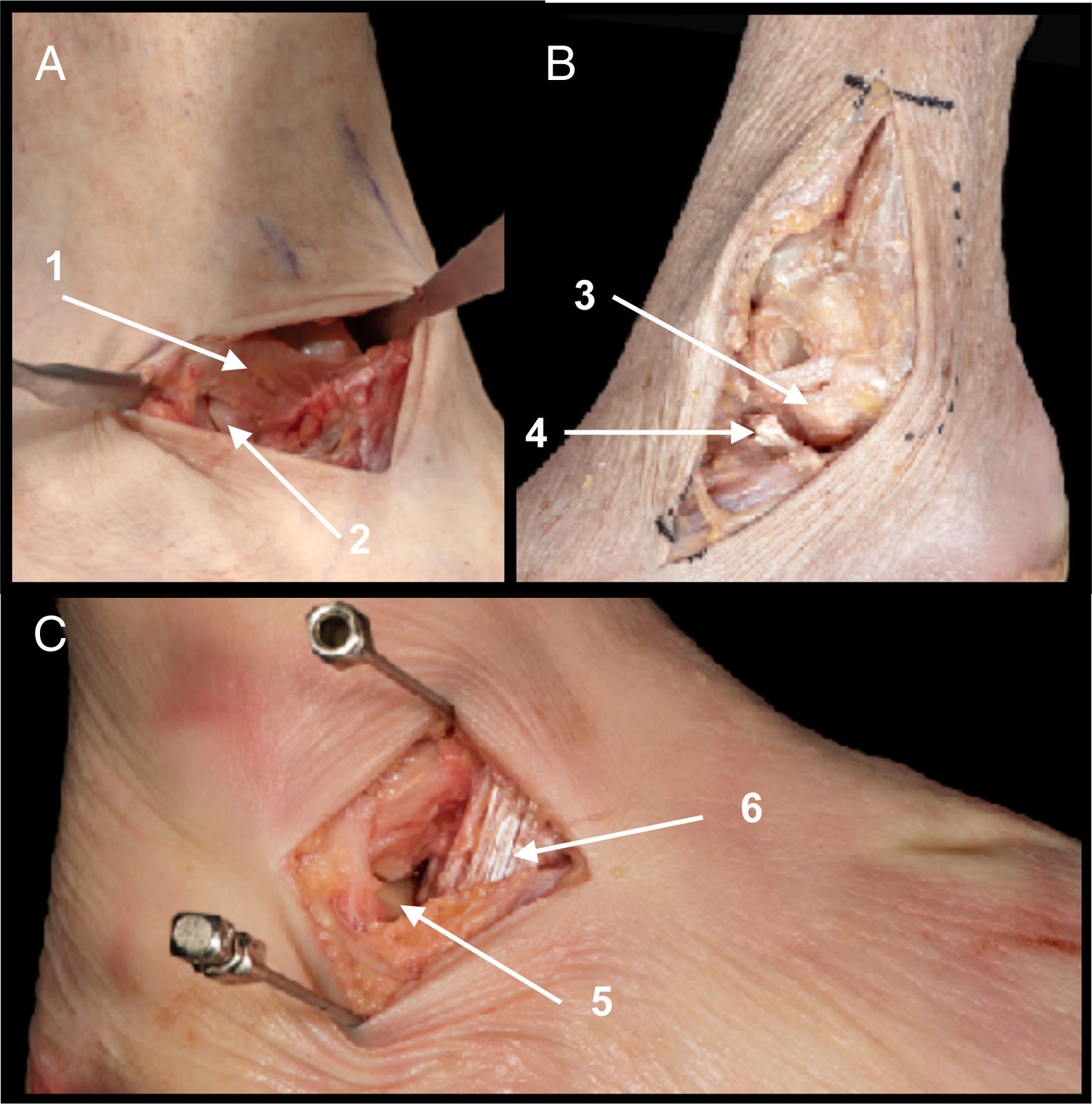

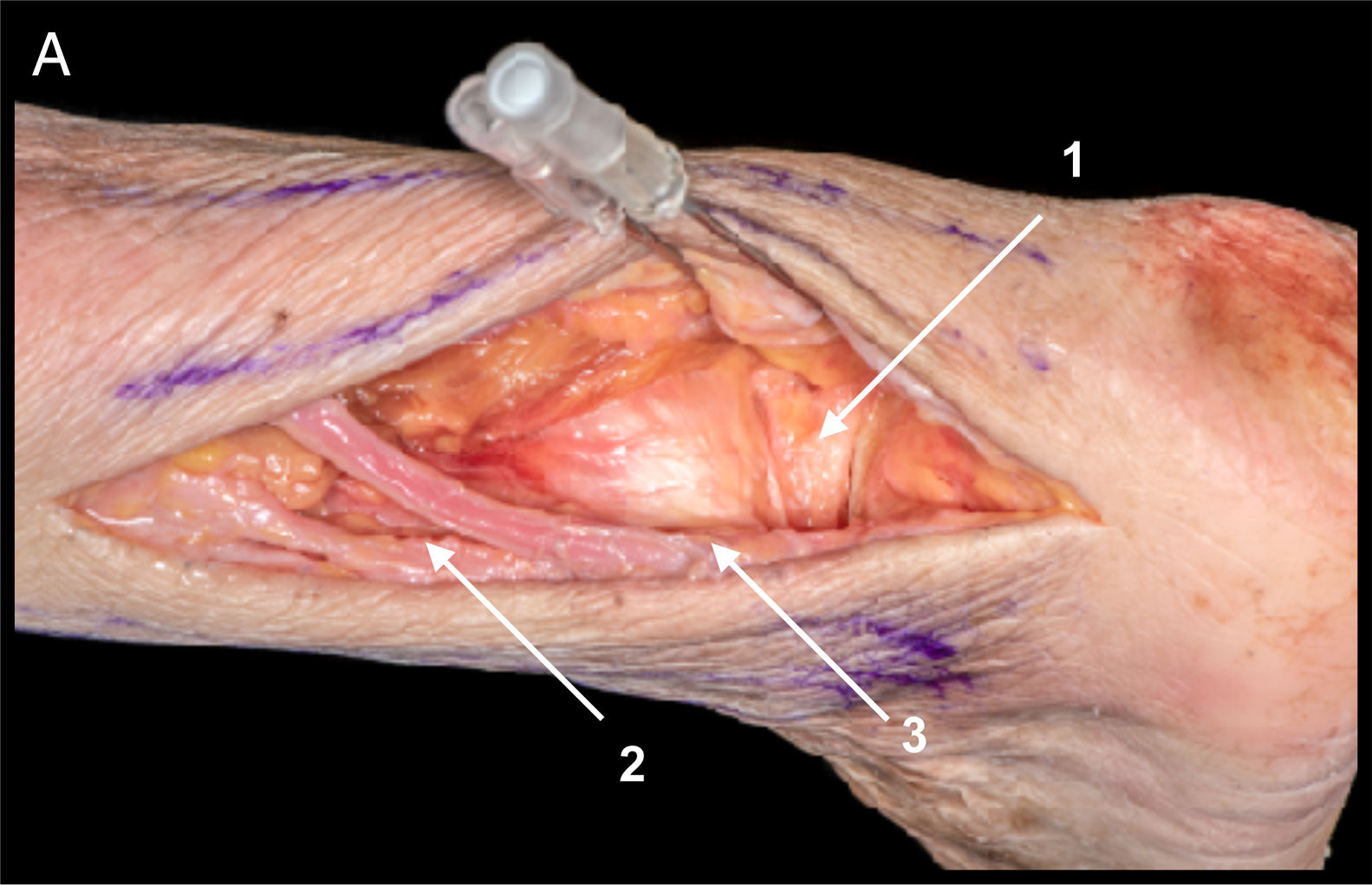

Anatomical details. Resection of adipose tissue from the sinus tarsi, proximal removal of extensor digitalis brevis (EDB) (if the fracture of the body has a posterior line, PCL sectioning may be necessary to view the most posterior section of the talus, and occasionally fibula osteotomy may need to be performed. PCL sectioning must be repaired with simple suture after talus synthesis has been performed),14 sectioning of the lateral talocalcaneal ligament and of the interosseous ligament, transversal sectioning of theATFL which will be subsequently repaired with simple suture with non-resorbable thread (Fig. 4A).

A. Extended anterolateral route. After sectioning of the ATFL (1) and lateral talocalcaneal ligament (2) proximal removal of the EDB (3) is performed to view the neck of the talus.

B. Structures at risk. Medial dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial fibular nerve (4), extensor digitalis longus (5), intermediate dorsal cutaneous branch of the superficial fibular nerve (6), peroneal tendons (7) and branches of the sural nerve (8).

In contrast to the Ollier route used to view the Chopart joint for performing triple arthrodesis, in this route there is no opening of the calcaneocuboid capsule and therefore sectioning of the bifurcate ligament is not necessary.

Structures at risk. Superficial fibular nerve and branches, extensor digitalis longus tendon, peroneal tendons and branches of the sural nerve (Fig. 4B).

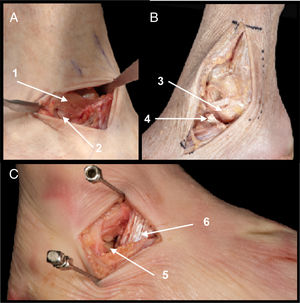

Approach with medial osteotomyIndicationsOsteochondral fractures of the medial talar dome.

Field of view. Medial talar dome (quadrants 1, 4 and 7).15–18

ApproachAnatomical references. From 5 cm proximal to the malleolus up to 3 cm distal and anterior to the talonavicular joint. Incision approximately from 8−10 cm.

Anatomical details. Sectioning of the superficial anterior deltoid ligament, part of the anterior tibiotalar fascicle and the anterior capsule with posterior repair, osteotomy perpendicular to the joint protecting the posterior tibial tendon (Fig. 5A).

A. Osteotomy of the tibial malleollus. Sectioning of the superficial and deep deltoid (anterior tibiotalar fascicle and tibionavicular fascicle) and articular capsule (1). Posterior tibiotalar fascicle of the deep deltoid ligament (2). Posterior tibial tendon (3).

B. Exposure of the internal talar dome. Greater saphenous vein injected with latex (4) and posterior fascicles of deep deltoid ligament (5) and posterior tibial tendon (6).

Malleolus drilling is advised prior to the osteotomy to facilitate subsequent synthesis with screws and to terminate the osteotomy with osteotome, to provide greater precision and avoid chondral damage.

Structures at risk. Posterior tibial tendon, internal saphenous nerve and greater saphenous vein, posterior fascicles of the deep deltoid ligament from risk of damaging vascularity.7–9 (Fig. 5B).

Fibula osteotomy routeIndicationFracture of the lateral talar body and osteochondral lesions in the middle and lateral quadrants of the talar dome (quadrants 2, 5, 8 y 3, 6 and 9).15–18

Field of view. Lateral talar body.

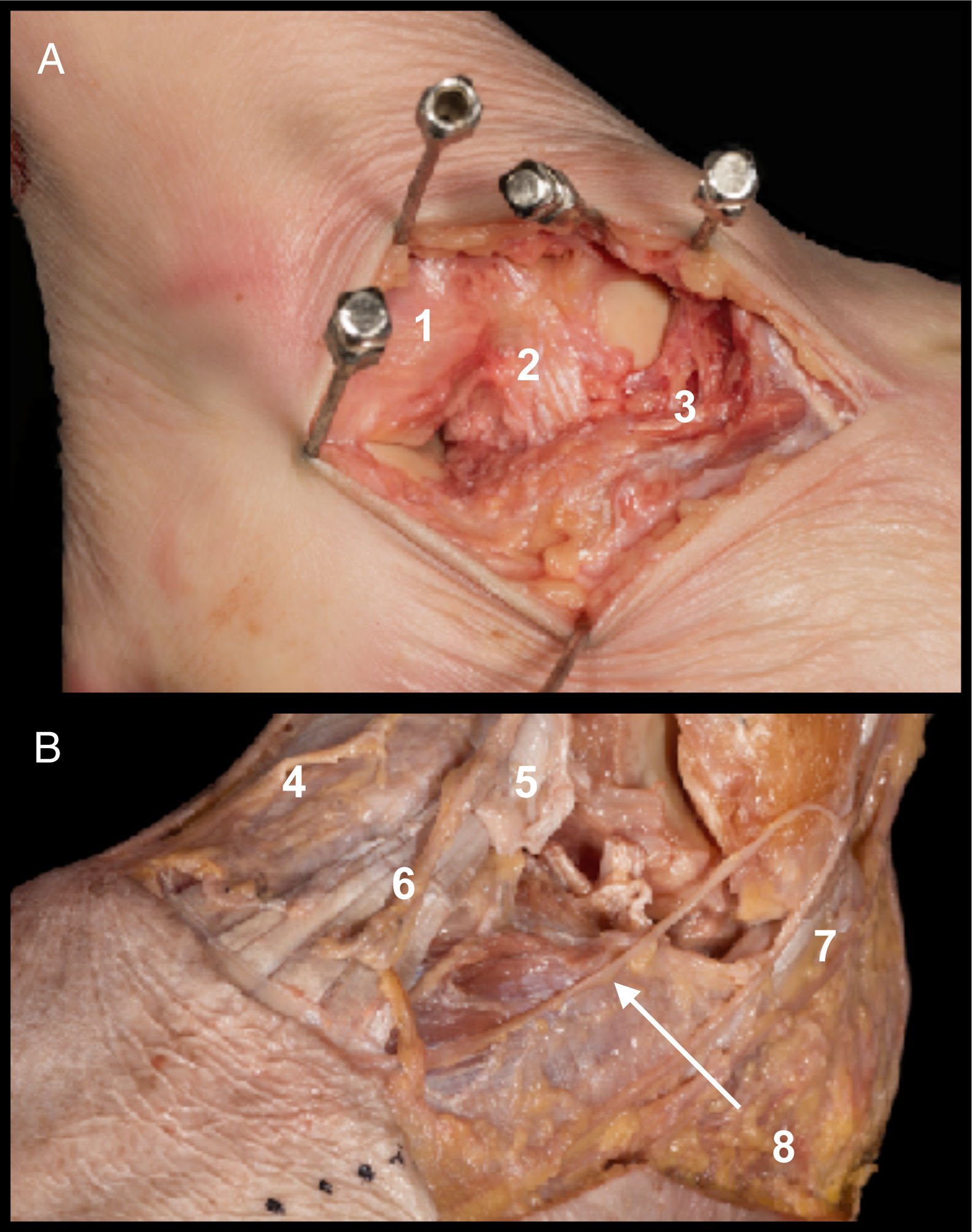

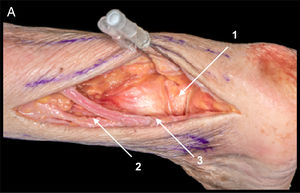

ApproachAnatomical references. From 7 cm proximal to the peroneal malleolus up to 3 cm distal following the direction of the 4thMT. Incision of approximately 9−10 cm.

Anatomical details. Section of the anterior syndesmosis and of the ATFL (Fig. 6A) (after sectioning the anterior syndesmosis and ATFL subsequent repair is required using simple suture or bone anchors to reestablish ankle stability), necessary for the rotation of the fibular malleolus. Transverse osteotomy of the fibula at 4 cm of the fibula protecting the peroneal tendons. External rotation of the fibula (the fibula calcaneal ligament does not need to b sectioned to achieve rotation of the fibula).

Structures at risk. Superficial fibular nerve and its branches, peroneal tendons and perforating peroneal artery (Fig. 6B).

Route with bilateral osteotomyIndicationsTalar body fractures: Comminuted fractures or chip fractures of the posterior body.

Field of view. Body and talar dome. The previously described routes may be combined (MO and LO). This improves vision of the most posterior part of the talar body and aids reduction and synthesis of the fracture. It appears to preserve talar vascularity on reducing the dissection of soft tissues, although no definitive studies exist to confirm this.14

ApproachThe same references, anatomical planes and previously described risks.

Posterolateral routeIndicationsFracture of the lateral tubercle of the posterior process of the talus. Control of the posterior talar joint. Chondral lesions of the posterior talar dome (quadrants 7, 8 and 9).15–18

Field of view. Posterior process of the talus, posterior talar dome and posterior talar joint.

ApproachAnatomical references. Approach of approximately 8−10 cm between the achilles tendon and the peroneal tendons.

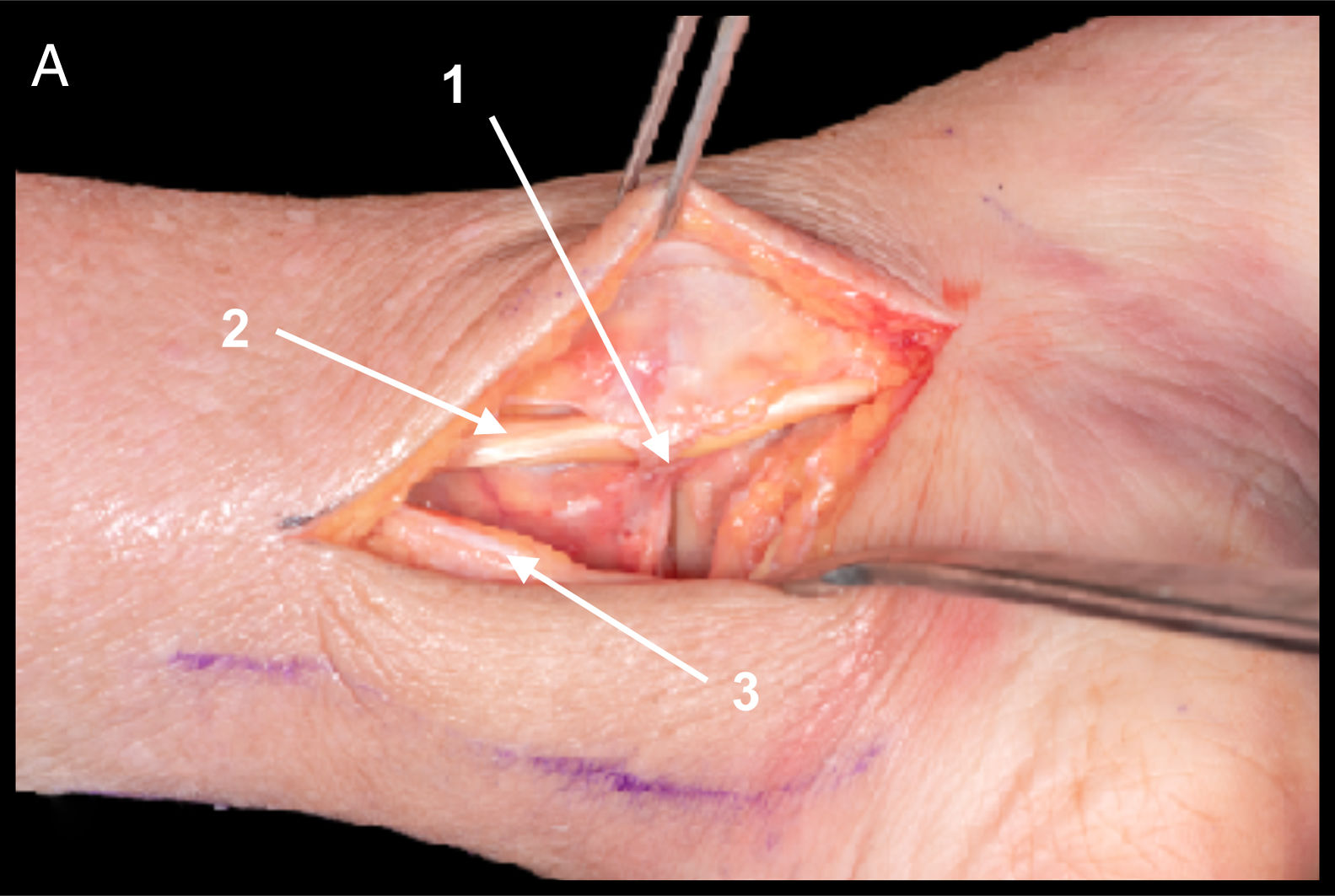

Anatomical details. Dissection between the between the achilles tendon and the peroneal tendons following identification of the sural nerve and small saphenous vein. Identification and medialisation of the flexor hallucis longus which will protect the neurovascular bundles. Sectioning of the posterior tibiotalar ligament and the posterior intermalleolar ligament (Fig. 7A) (after sectioning part of the posterior ligament complex, repair must be performed using simple suture or bone anchors).

PL. Field of view of the posterior process of the talus. Approach between peroneal tendons and FLH and achilles tendon. For viewing the posterior subtalar ligament opening of the posterior tibiotalar ligament and of the posterior intermalleolar ligament is required (1). The main risks are: sural nerve (2) and lesser saphenous vein (3).

Structures at risk. Sural nerve with its calcaneal branch, small saphenous vein, peroneal tendons, the perforating branch of the peroneal artery (crossing the interosseous membrane posteriorly, approximately 3 cm from the distal end of the fibula). The posterior tibial neurovascular bundle is protected by the flexor hallucis longus.

Posteromedial routeIndicationsFracture of the posterior process of the talus (medial tubercle of the posterior process of the talus). Control of the posterior subtalar joint. Osteochondral lesions (quadrants 7 and 8).15–18

Field of view. Posteromedial region of the talus and posterior subtalar region.12,13

ApproachAnatomical references. From 7 cm proximal to the tibial malleolus up to 1 cm distal and slightly posterior.

Anatomical details. Dissection between posterior tibial tendon and flexor digitorum longus tendon to avoid neurovascular bundle (Fig. 8A).

Structures at risk. Neurovascular bundle, posterior tibial tendon, flexor digitorum communis of the first toe.

Results and discussionThe most common fractures of the talus are the neck of the talus. Standard observation of these fractures uses AM or AL routes but at times exposure through these routes is insufficient and the majority of current literature therefore advocates the double combined route of AL and AM as the most effective in fractures of the neck of the talus. This route enables optimized control of reduction and synthesis although an anterior route has also been described leading to good observation of fractures of the neck of the talus.11 The authors believe that in the vast majority of cases it is essential to undertake the double approach, combining the AL route or the extended anterolateral route with the AM route to achieve accurate reduction, with continuous control of the 2 sides of the talus to prevent any valgus varus displacement and poorly positioned unions, which would change the bone centerline and therefore lead to a change in the biomechanics of the foot, with disastrous results.

In the case of these fractures it is essential to perform a CAT scan previously so as to accurately plan surgery and ensure meticulous reduction. A pre-surgical study will lead to the best approach route for each case, the one offering the greatest field of vision whilst respecting structures and preventing loss of blood supply as much as possible.

This article describes the extended anterolateral route, a modified Ollier approach used as standard for triple arthrodesis of the tarsus. This route is recommended for complex fractures of the head with proximal line to the neck or body (with involvement or non-involvement of the lateral process) because it provides visualization of its entire extension. This could also be combined AM approach to optimize control of the fracture.

After the anatomical study the authors deduced that in fractures of the talar body EDB removal could be avoided, but not sectioning of the ATFL. In contrast, for fractures of the head and neck of the talus removal of the EDB would be essential, and would scarcely alter the ligamentous structures of the lateral complex of the ankle.

For an approach to the posterior process of the talus some of the literature advocates the posteriomedial approach as a favourable route for exposure, and osteotomy of the posterior malleolus has even been described.19 In our experience the posteromedial route has no real practical uses, as this route presents with a high neurovascular risk due to its proximity with the posterior tibial bundle, and falls short of any advantage compared with the posterolateral approach.

Regarding osteochondral lesions, these should be approached in accordance with location. In quadrants 1, 2, 4 and 5 an anteromedial approach may be undertaken, in quadrants 2, 3, 5 and 6 approach would be anterolateral and in quadrants 8 and 9 it would be posterolateral. In many cases malleolar osteotomies would be necessary to achieve good exposure, especially in quadrants 4, 6 and 8.15–18 If there are osteochondral lesions in quadrant 7 osteotomy of the tibial malleolus is advocated, since with the posteromedial approach very little exposure is achieved and there is a high risk of damaging the posterior neurovascular bundle.

ConclusionsFractures of the talus are not common but they are considered to be serious lesions due to their associated complications. The most feared complication is necrosis of bone, which is due to the precarious vascularisation of this bone, owing to its extensive articular surface. This has traditionally resulted in treating this type of lesion as quickly as possible by surgeons who are at times not experienced and who are unfamiliar with the necessary approach routes.

The surgeon’s knowledge of the foot and ankle anatomy, together with the blood vessels irrigating the talus and their related contributions and locations, is key to the success of this type of surgical treatment.

FinancingThe authors received no financial assistance for undertaking this study. Neither did they sign any agreement by which they would receive benefits or fees from any business entity. This research did not receive any specific grants from public sector or business agencies or any non-profit-making entities

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gutiérrez García M, López Capdevila L, Vacas Sánchez E, Mota Gomes T, Pineda J, Santamaría Fumas A, et al. Estudio y descripción anatómica de vías de abordaje del astrágalo. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:272–280.