We reviewed the clinical features of post-traumatic infections produced by Clostri-dium celerecrescens reported in the literature. C. celerecrescens is an emerging pathogen involved in traumatic wound infection that progresses to deep infection and osteomyelitis.

MethodsWe found only 4 cases reported in the literature with enough data to be analysed and we added our own case and experience with this type of infection. The identification was performed by matrix-assisted desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI TOF) or API Gallery, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing were performed to confirm identification in all cases.

ResultsIdentification of the bacteria is discrepant according to the method used due to the genetic and phenotypic similarities of other species of the genus. Identification through MALDI-TOF and API gallery is not suitable for determining the specie, confirmation by 16S rRNA sequencing being necessary. Treatment of the infection included complex antibiotic combinations and surgical treatment together with skin and soft tissue dressings due to the persistence of the pathogen over time.

ConclusionThis report supports the pathogenic role of C. celerecrescens in post-traumatic infections and the need to improve the management of these difficult-to-treat infections.

Se ha realizado una revisión sobre las infecciones producidas por Clostridium celerecrescens que aparecen recogidas en la literatura. C. celerecrescens es un patógeno emergente relacionado con infecciones de heridas traumáticas que progresan a infecciones profundas y osteomielitis.

MétodoEn la literatura sólo se han encontrado 4 casos con suficientes datos para ser analizados; nosotros añadimos un nuevo caso y experiencia en el manejo de la infección. La identificación se realizó mediante espectrometría desorción/ionización láser asistida por matriz acoplada a un detector de tiempo de vuelo (MALDI-TOF) o mediante Galería API. Se realizó secuenciación del 16S rRNA en todos los casos.

ResultadosLa identificación de la bacteria fue discrepante según el método utilizado debido a las similitud fenotípica y genética con otras especies del mismo género. La identificación mediante MALDI-TOF y Galerías API no resulta adecuada para la determinación a nivel de especie, siendo necesaria la secuenciación del ARNr 16S. El tratamiento de la infección incluye combinaciones de antibióticos complejas y tratamiento quirúrgico junto con curas de piel y partes blandas debido a la persistencia de la bacteria a lo largo del tiempo.

ConclusiónEl presente estudio manifiesta el potencial patogénico de C. celerecrescens en infecciones postraumáticas y la necesidad de mejorar el manejo de estas infecciones.

The origin of post-traumatic osteomyelitis is the result of trauma or a nosocomial infection after trauma treatment, where pathogens reach the bone, proliferate in the damaged tissue and cause bone infection. Implants or open fractures favour the entry of anaerobes and gram-negative bacilli. Persistent bone infection favours chronic, often polymicrobial, osteomyelitis. Although all bones can be involved, osteomyelitis mainly occurs in the lower limbs. Appropriate therapy should include drainage and debridement of the site accompanied by antibiotic treatment, which in most cases can be based on the microbiological result.1

The Clostridium genus is formed by a heterogeneous group of sporulated gram-positive bacilli that are present in the environment and colonise the intestinal tract of mammals.2 The genus comprises over 220 species of strict anaerobes (some of which may be aerotolerant), but only a few are considered clinically relevant.3 Due to the large number of species in the genus, some Clostridium spp. may not be correctly identified. This is the case with Clostridium celerecrescens, a species that shares the same biochemical properties and sensitivity of other species of the Clostridium genus.2,4,5 The first case of C. celerecrescens was published in 1989 and isolated from cow dung in a methanogenic cellulose-enriched culture. The microorganism was given its name due to its rapid growth.6

To date, more than 800 cases of bone infections caused by anaerobes over the last 50 years have been published. In fact, the Clostridium genus is involved in many cases of long bone infections.7 Only 4 articles have been published to date on osteomyelitis caused by C. celerecrescens; there was a history of post-traumatic bone fracture in all cases. We present a new case and a review of the published cases, with the aim of appropriately identifying and managing osteomyelitis caused by C. celerecrescens.

Material and methodsA search was conducted from 1980 onwards for all articles in English and Spanish in which the keywords Clostridium celerecrescens and/or Clostridium sphenoides appeared.

Identification was carried out by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) or API gallery. 16S rRNA sequencing was performed in all cases. Mass sequencing was performed in one case.8

The minimum inhibitory concentration was determined by E-test of anaerobes in all cases. In our case, the interpretation of the minimum inhibitory concentration was made according to the criteria for gram-positive anaerobes of the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (EUCAST 2016/2017)

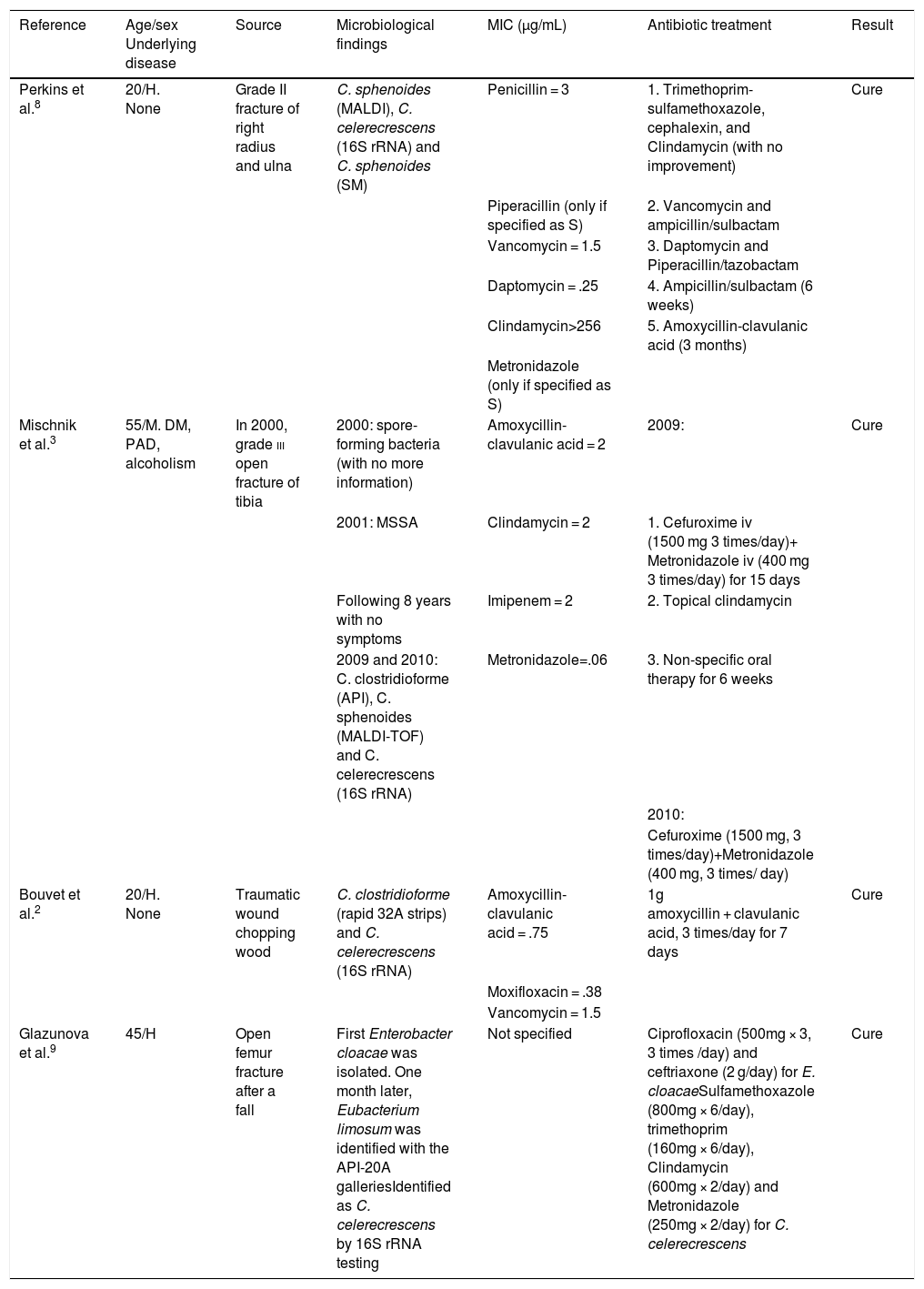

ResultsWe found 4 cases in the literature and we add a further case with similar characteristics to the published cases. These articles’ references are shown and summarised in Table 1.

Summary of the 4 cases published in the literature related to Clostridium celerecrescens.

| Reference | Age/sex Underlying disease | Source | Microbiological findings | MIC (μg/mL) | Antibiotic treatment | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perkins et al.8 | 20/H. None | Grade II fracture of right radius and ulna | C. sphenoides (MALDI), C. celerecrescens (16S rRNA) and C. sphenoides (SM) | Penicillin = 3 | 1. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephalexin, and Clindamycin (with no improvement) | Cure |

| Piperacillin (only if specified as S) | 2. Vancomycin and ampicillin/sulbactam | |||||

| Vancomycin = 1.5 | 3. Daptomycin and Piperacillin/tazobactam | |||||

| Daptomycin = .25 | 4. Ampicillin/sulbactam (6 weeks) | |||||

| Clindamycin>256 | 5. Amoxycillin-clavulanic acid (3 months) | |||||

| Metronidazole (only if specified as S) | ||||||

| Mischnik et al.3 | 55/M. DM, PAD, alcoholism | In 2000, grade iii open fracture of tibia | 2000: spore-forming bacteria (with no more information) | Amoxycillin-clavulanic acid = 2 | 2009: | Cure |

| 2001: MSSA | Clindamycin = 2 | 1. Cefuroxime iv (1500 mg 3 times/day)+ Metronidazole iv (400 mg 3 times/day) for 15 days | ||||

| Following 8 years with no symptoms | Imipenem = 2 | 2. Topical clindamycin | ||||

| 2009 and 2010: C. clostridioforme (API), C. sphenoides (MALDI-TOF) and C. celerecrescens (16S rRNA) | Metronidazole=.06 | 3. Non-specific oral therapy for 6 weeks | ||||

| 2010: | ||||||

| Cefuroxime (1500 mg, 3 times/day)+Metronidazole (400 mg, 3 times/ day) | ||||||

| Bouvet et al.2 | 20/H. None | Traumatic wound chopping wood | C. clostridioforme (rapid 32A strips) and C. celerecrescens (16S rRNA) | Amoxycillin-clavulanic acid = .75 | 1g amoxycillin + clavulanic acid, 3 times/day for 7 days | Cure |

| Moxifloxacin = .38 | ||||||

| Vancomycin = 1.5 | ||||||

| Glazunova et al.9 | 45/H | Open femur fracture after a fall | First Enterobacter cloacae was isolated. One month later, Eubacterium limosum was identified with the API-20A galleriesIdentified as C. celerecrescens by 16S rRNA testing | Not specified | Ciprofloxacin (500mg × 3, 3 times /day) and ceftriaxone (2 g/day) for E. cloacaeSulfamethoxazole (800mg × 6/day), trimethoprim (160mg × 6/day), Clindamycin (600mg × 2/day) and Metronidazole (250mg × 2/day) for C. celerecrescens | Cure |

MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; DM: diabetes mellitus; PAD: peripheral artery disease; iv: intravenous; MSSA: Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; MS: massive sequencing.

We present the case of a 39-year-old women with no underlying disease who was involved in a car accident in 2016 and whose main injuries were an open, bilateral diaphyseal femur fracture and multiple rib fractures. After initial stabilisation, the patient underwent emergency surgery in another centre, with reduction and intramedullary nailing of both femur fractures. She made satisfactory progress in the immediate postoperative period and was discharged from hospital.

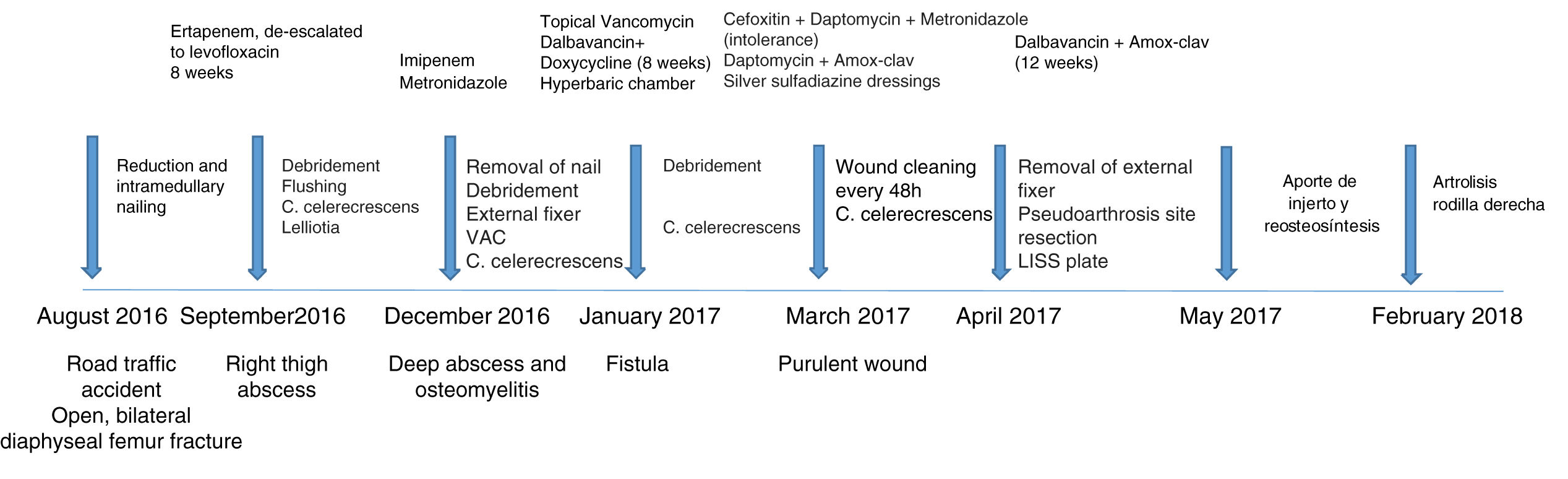

In September 2016, the patient attended our centre’s emergency department with an abscess in her right thigh that required draining in the operating theatre. Intra-operative cultures of Lelliottia amnigena and Clostridium spp. were isolated. Therefore, given these findings, we decided to re-operate and perform debridement, copious flushing, and antibiotic treatment. On completion of the antibiotic treatment, the L. amnigena was eradicated. However, Clostridium spp. continued to be isolated in cultures until March 2017 despite different combinations of antibiotics and more than 18 debridements. Fig. 1 shows the patient’s clinical progress along with the prescribed antibiotic treatment.

The patient is currently undergoing rehabilitation treatment and needs to use a crutch and a raised insole of 7 mm for the lower left limb due to dysmetria. She has shown no further clinical or analytical signs of infection during follow-up to date and the risk-benefit of a total right knee replacement is being considered.

In the 5 cases, MALDI-TOF identified C. sphenoides and the API gallery Clostridium clostridioforme.

16S rDNA gene sequencing related in all cases to C. celerecrescens. In our case, the 16S rDNA gene was sequenced with primers 16S-F and E533R and related to C. celerecrescens by 99% (QC 100%, Ident 99%) (NCBI accession no. AB 910754.1).

Antibiotic sensitivity, in our case, was: benzylpenicillin = 4, ampicillin≤4, amoxycillin-clavulanic acid≤4/2, piperacillin-tazobactam = 16, imipenem = 8, clindamycin>256, metronidazole≤4 and vancomycin = .5 μg/mL. The minimum inhibitory concentration of the other cases is shown in Table 1. It is worth mentioning that although moxifloxacin showed a good profile against this bacterium, quinolone treatment was not selected as therapy in any of the published cases except the last, where C. celerecrescens was isolated from an abscess

DiscussionPost-traumatic osteomyelitis can be caused by a wide range of microorganisms, such as Aeromonas, Pseudomonas and other enterobacteria, most of which are present in soil, water, and organic detritus.9–11 Therefore in the case of open fractures anaerobic infection must be suspected where Clostridium is particularly relevant. The virulence factors of some of some Clostridium species in bone and soft tissues are not completely known,4,6 but various studies indicate that spore production, different degrees of mobility and the production of enzymes and toxins can cause necrosis and leukocyte lysis.

C. celerecrescens appears in all the cases shown in the literature on post-traumatic osteomyelitis. This bacterium was isolated in different samples and at different times. In fact, in our case, the patient suffered her accident in August 2016 and C. celerecrescens continued to be isolated after more than 7 months, and antibiotic treatment ended in July 2017.

Identification by MALDI-TOF and by the API gallery is not suitable for testing at species level, as they are not able to discriminate between C. sphenoides and C. celerecrescens. In fact, in 2 cases isolation of both genera in the same sample was reported using 2 different methods; identification was subsequently confirmed by 16S rRNA. However, in one case, mass sequencing was inconsistent with 16S rRNA, possibly because the primer used in the 16S rRNA analysis was non-specific. One possible explanation for why the bacterium is rarely isolated from clinical samples may be its phenotypic and genetic similarity to other species in the genus. For this reason, molecular testing is necessary

In the published cases, treatment included complex combinations of antibiotics, in all cases with anaerobic coverage. It is important to highlight that within the C. clostridioforme group, which includes C. celerecrescens, antibiotic resistance is relatively frequent. In our case, the empirical treatment was not adequate due to the choice of carbapenems, in vitro sensitivity to imipenem being intermediate. Despite adjusting the treatment with specific antibiotics, the bacteria could not be eradicated, hyperbaric therapy and dalbavancin treatment were required for more comfortable management of the patient. Further study of a larger number of cases is needed to obtain more representative data on the antibiotic sensitivity of this species.

On the other hand, we must bear in mind that treatment of osteomyelitis must be combined with debridement surgery to control the focus of infection. How surgery will affect the patient’s progress should be considered when evaluating a case.

Similarly, appropriate treatment of the skin and soft tissue is essential for bone tissue recovery. We believe it is relevant to point out that in this case silver-sulfadiazine-impregnated dressings resulted in the best outcome for the patient. This product is widely used in the treatment of other injuries such as burns, but there is no evidence of its use in soft tissue coverage in infectious disease.11

In all cases, the patients made a full recovery, although the bacteria were isolated repeatedly over time.

Intensive surgical treatment, together with skin and soft tissue dressings, is essential. This article supports the pathogenic role of C. celerecrescens in causing rare and difficult-to-treat infections. For this reason, molecular testing is important to identify related species correctly.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Mormeneo Bayo S, Ferrer Cerón I, Martín Juste P, Lallana Dupla J, Millán Lou MI, García-Lechuz Moya JM. Osteomielitis postraumática difícil de tratar: papel del Clostridium celerecrescens. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2020;64:281–285.