We present a case series report of patients with Charcot foot treated by single-stage surgery with static circular fixation.

Material and methodRetrospective review of 10 cases treated with static circular external fixation since 2016, with the following inclusion criteria: (1) Deformity with any of the following: ulcers, osteoporosis, osteomyelitis or instability; (2) peripheral neuropathy; (3) failed orthopaedic treatment. Exclusion criteria: (1) peripheral vascular obstruction without revascularization; (2) inability to comply with treatment; (3) non-ambulatory patients; (4) medical contraindication for surgery. Of the 10 patients, 7 men and 3 women, 6 had involvement of the left foot and 4 of the right one. The average age of our patients was 58 years (range 39–71). We also evaluated Eichenholtz and Brodsky classification, presence of ulcers, osteomyelitis and instability. All were treated with circular external fixation with a medium follow up of 17 months (11–24 months). Postoperatively we evaluated limb salvation, ulcer healing, stability and re-ulcerations.

ResultsIn all patients a functional plantigrade foot was achieved, cutaneous ulcer healed without recurrence. Four cases presented superficial pin infection, solved with local wound care. We had wire ruptures in 2 cases, which did not require replacement. We had a traumatic tibial fracture after frame removal, orthopedically solved. All patients were satisfied and would opt for the same technique, if necessary.

ConclusionsThe objectives of the study in Charcot foot are to avoid amputation and achieve a functional plantigrade foot, without ulcer.

Single-stage surgery with static circular external fixation is reproducible in our country, and also a valid technique for those cases in which internal fixation may not be the best option.

Presentamos los resultados de una serie de casos de pie de Charcot tratados mediante cirugía en un solo tiempo con fijador circular estático.

Material y métodoRevisión retrospectiva de 10 casos tratados con fijación externa circular estática desde 2016, con los siguientes criterios de inclusión: 1) deformidad asociada a alguno de los siguientes signos: úlcera cutánea, osteomielitis o inestabilidad articular; 2) neuropatía periférica, y 3) fallo del tratamiento ortopédico previo. Criterios de exclusión: 1) obstrucción vascular periférica sin revascularizar; 2) incapacidad para cumplir el tratamiento; 3) pacientes no deambulantes, y 4) contraindicación médica para la cirugía. De los 10 pacientes, 7 hombres y 3 mujeres, 6 tenían afectación del pie izquierdo y 4 del derecho. La edad promedio de nuestros pacientes era de 58 años (rango 39–71). Valoramos además estadio de Eichenholtz, clasificación de Brodsky, presencia de úlceras cutáneas, osteomielitis e inestabilidad. Todos los pacientes fueron tratados con fijación circular con un seguimiento medio de 17 meses (rango 11–24 meses). Postoperatoriamente, valoramos la conservación de la extremidad, curación de la úlcera cutánea, estabilidad e índice de reulceraciones.

ResultadosEn todos los pacientes se consiguió un pie plantígrado funcional, curación de la úlcera cutánea sin recidiva de la misma. Cuatro casos presentaron infección cutánea en las agujas, resuelta con cuidados locales. Evidenciamos rotura de aguja en 2 casos, que no requirieron recambio. Todos los pacientes están satisfechos y optarían por la misma técnica, de ser necesario.

ConclusionesEn el pie de Charcot los objetivos son evitar la amputación y conseguir un pie plantígrado funcional, sin úlcera cutánea.

La cirugía en un solo tiempo con fijación externa circular estática es una técnica reproducible en nuestro medio, válida además para aquellos casos en que la fijación interna puede estar contraindicada.

Diabetes mellitus is highly prevalent worldwide, with incidence rates ranging between 4% and 6.5%.1 In Spain prevalence is 13.8%.2 The World Health Organisation states this is the 21st century epidemic2 and its complications have high impact on the health service.3

Charcot foot which is a consequence of diabetic neuropathy, is a inflammatory process with different degrees of bone destruction and deformity.4 Its prevalence is approximately 7.5% of all diabetic patients.5 Between 9% and 35% of these patients will present with a bilateral lesion.6

Charcot foot patients, with or without bone infection, are highly costly for healthcare systems.7

In Charcot foot there is a loss of protective sensitivity and high local bone turnover, together with repeated load on injured structures8 during normal ambulation. The combination of these elements leads to a fragile and insensate foot.

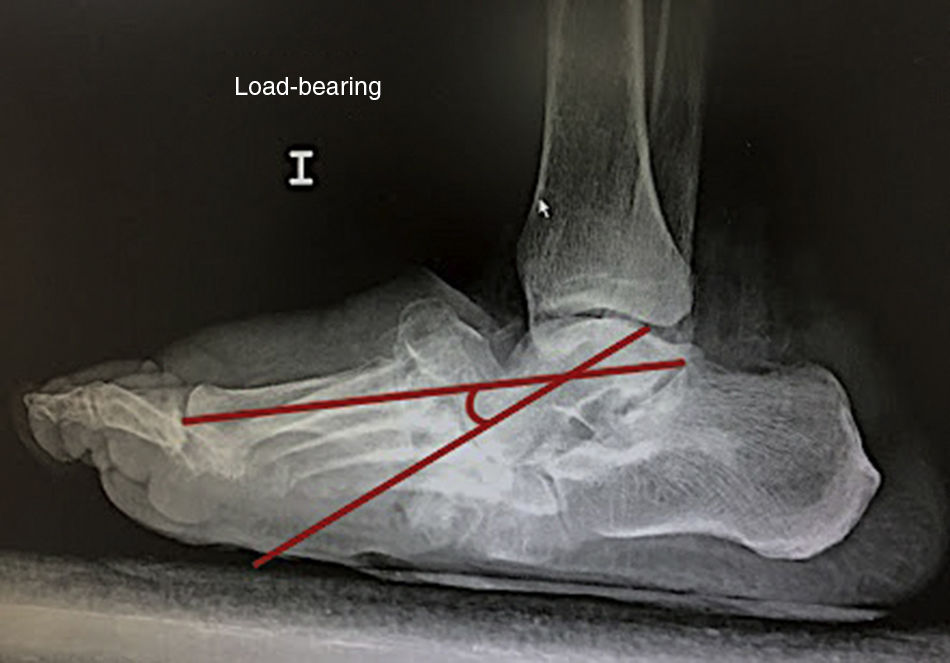

Diagnosis of Charcot in active phase is usually clinical (distal neuropathy, increase in volume and reddening of the foot), whilst in the “non-active” phase characteristic deformities are prominent, such as rocker bottom foot (Fig. 1) and axial deformities of the ankle.9

In their radiographic analysis Wukich et al.10 established a limit of 27 degrees of alteration in Meary's line as a predictor of the appearance of ulcers (Fig. 2).

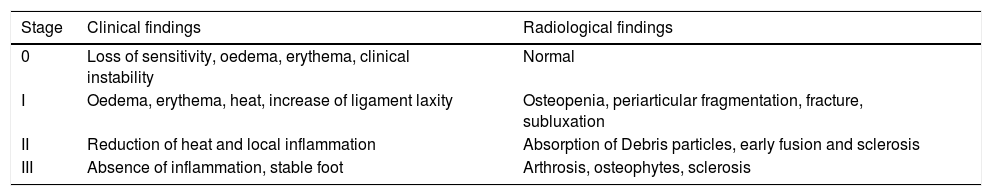

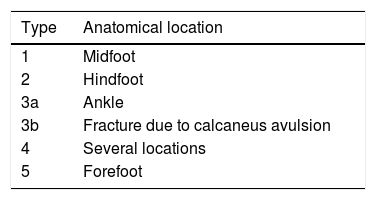

Eichenholtz's11 classification (Table 1) defines the clinical stage of Charcot foot and the classification by Brodsky12 (Table 2) anatomically situates the lesion, with the midfoot being the most frequently affected region. It has recently been proposed to simply divide the Charcot foot into active or inactive.13

Modified Eichenholtz classification. Charcot neuroarthropathy.

| Stage | Clinical findings | Radiological findings |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Loss of sensitivity, oedema, erythema, clinical instability | Normal |

| I | Oedema, erythema, heat, increase of ligament laxity | Osteopenia, periarticular fragmentation, fracture, subluxation |

| II | Reduction of heat and local inflammation | Absorption of Debris particles, early fusion and sclerosis |

| III | Absence of inflammation, stable foot | Arthrosis, osteophytes, sclerosis |

Amputation is the most essential complication to avoid in Charcot foot.14 The mortality of a diabetic patient after an amputation is higher than that of many types of cancer.15 Furthermore, evidence suggest that it is cheaper to provide these patients with surgical reconstruction than to amputate extremities.16 Due to this, the aim of treatment is to achieve a plantigrade, functional foot with structural stability.17

Non-surgical treatment of patients with Charcot foot is effective in 60% of cases.17 Surgical treatment was indicated on rare occasions due to unpredictable results. At present there is evidence to suggest that early surgical treatment may have better outcome with correction and stabilisation of the deformity.18

Poor bone quality in diabetics seems to be a determining factor in the failure of internal fixation.19 For this reason Sammarco et al.20 proposed superconstruction, which were recently designed with specific plates.19 The presence of infectious bone processes and soft tissues, and the precarious skin status may also be contraindicative of internal osteosynthesis.19

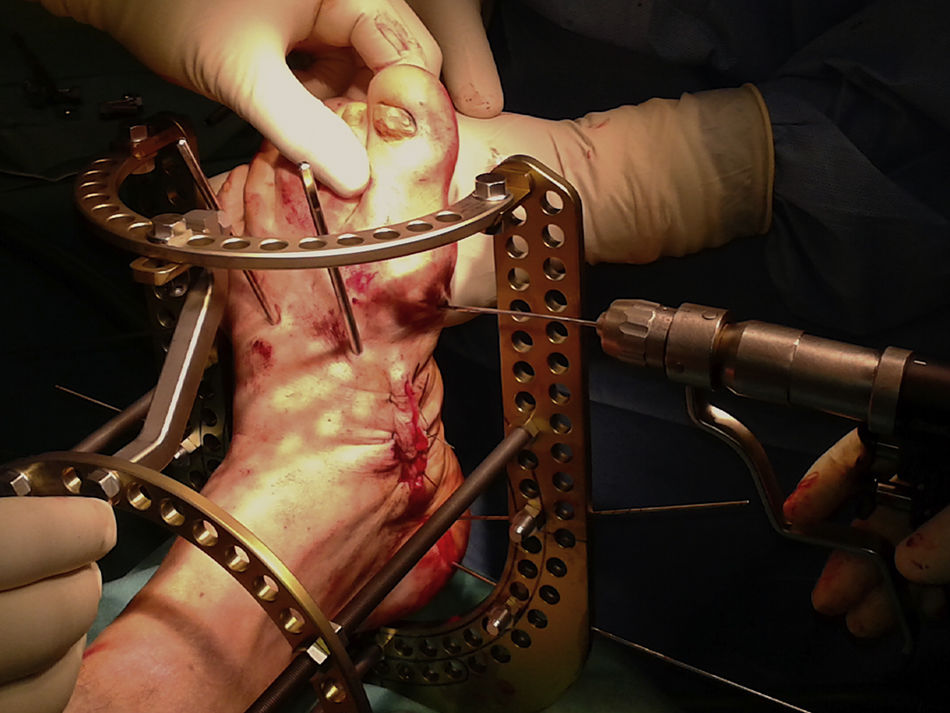

Several authors19,21–23 describe static circular fixation (Fig. 3), which prevents amputation and has excellent outcomes. We therefore tried to confirm the reproducibility of this technique in this series in our environment.

Material and methodsRetrospective review of 10 patients with Charcot foot treated by single stage surgery with static circular fixation, by the same surgeon of the foot and ankle department of our hospital, from 2016.

Inclusion criteria taken into account were: (1) deformity associated with any of the following signs: cutaneous ulcer, osteomyelitis and instability, (2) peripheral neuropathy, and (3) orthopaedic treatment which had previously failed. The latter consisted in total contact cast, orthopaedic boots and specific insoles.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) patients with peripheral vascular obstruction without revascularisation; (2) patients with inability to comply with treatment; (3) non-ambulatory patients, and (4) medical contraindication for surgery.

Of the 10 patients, 7 men and 3 women, 6 had involvement of the left foot and 4 of the right one. The average age of our patients was 58 (range 39–71).

With regard to Brodsky's classification, 6 cases presented with radiological involvement in midfoot, 3 in ankle and one in subtalar joint. All patients were in Eichenholtz stage III. Eight cases presented with cutaneous ulcers (6 lateral plantar, 2 lateral malleolus) with clinical suspicion of osteomyelitis (bone exposure, bone contact, radiographical changes, history of osteomyelitis) on surgery and 2 cases were affected by an unstable deformity with a high risk of ulceration.

Single stage surgical treatment was completed using a static circular fixation system, with a mean follow-up of 17 months (range between 11 and 24 months), following the indications recommended by Pinzur,24 as described overleaf.

Surgical techniqueAfter epidural or regional blockage, a pneumatic vacuum sleeve was inserted at thigh level to induce ischaemia, only during the osteotomy phases. The patient was in supine position.

Correction of hindfoot equinusPercutaneous tenotomy was performed on the achilles tendon with 3 para-achilles incisions at approximately 3cm distance from one another.

Modelling osteotomy and excision of the osteomyelitis focusA medial and a lateral approach was made on the midfoot. If the deformity affected the hindfoot, the approach was adapted to the affected joint. Dissection was performed up to a subperiosteal plane, creating a workspace which respected the tendon and neurovascular elements.

Osteotomy wedge was performed to achieve the final objective: a plantigrade and correctly aligned foot. Bone samples were sent to the microbiological and pathological anatomy department. The reduction was then fixed with two 3.2mm diameter Steinman pins, inserted through the dorsal of the midfoot (Fig. 4). Control with image intensifier verifies the obtainment of a plantigrade foot.

Excision of the plantar ulcer and debridementIf there is a skin ulcer, it is resected and sent for microbiological analysis. Any fluid collection in the area is drained. Partial closure of the plantar ulcer is made with spaced stitches of non absorbable material. If skin closure without stress is not possible, we recommend a second attempt at closure or assisted by negative pressure wound therapy.

Circular fixation methodWe used the Distraction Osteogenesis Ring System® (DePuy Synthes Johnson & Johnson) static circular external fixator with standard montage of 2 rings and a base for the foot.

1.8mm reduction transfixion wires were used for connecting the foot with the circular fixator. We inserted the first 2 wires in the hindfoot with a 30 degree angle between them.

In the Charcot midfoot, the distal wire to the area of the osteotomies was used to compress the focal point (Fig. 5). We then inserted 2 wires in each of the 2 tibial rings with a 30 degree angle between both.

It is vital to be precisely aware of the anatomical disposition of the neurovascular elements at each level of transfixion wire insertion and to avoid areas of conflict between the skin and the different fixator components.

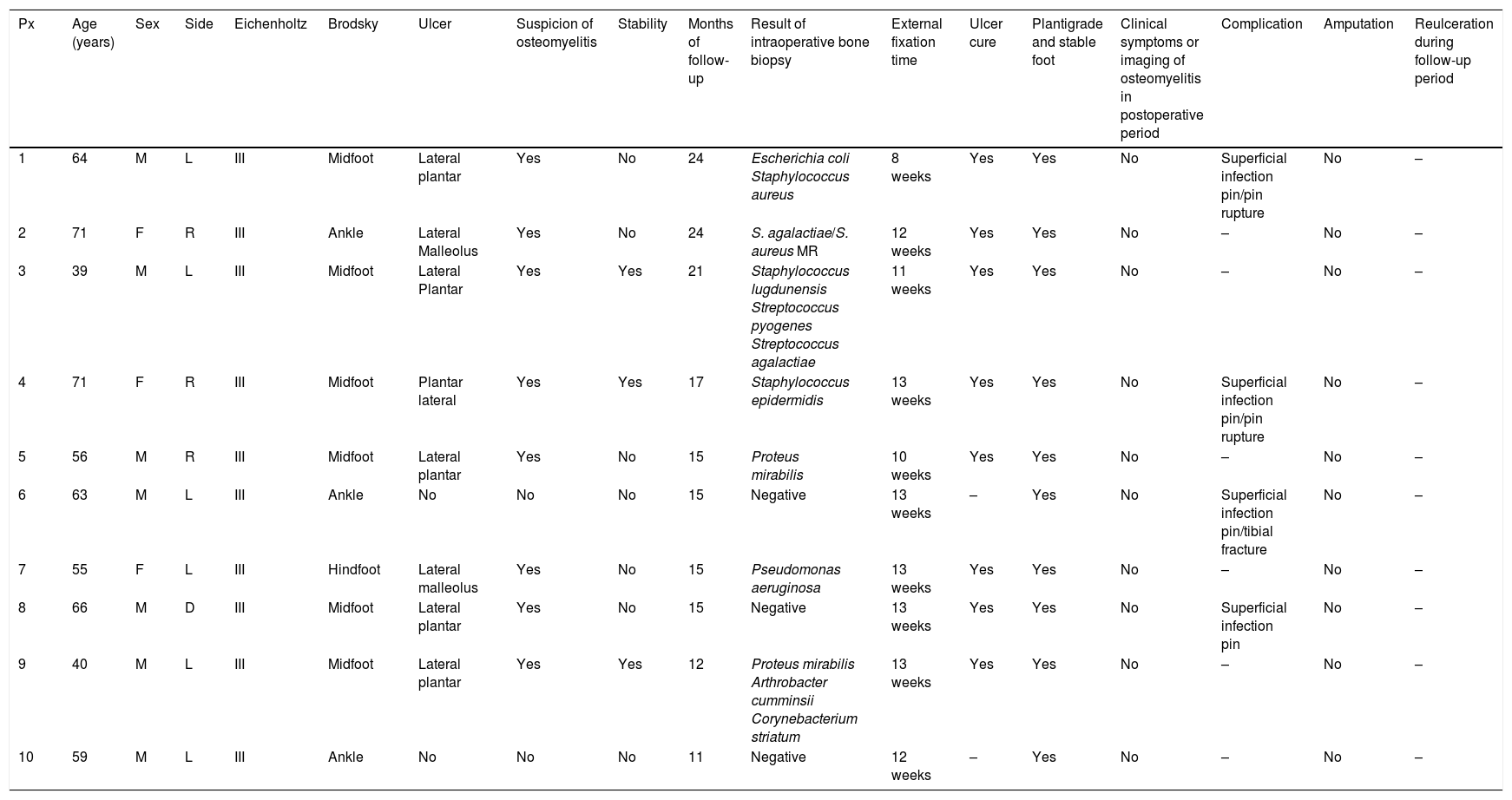

Postoperative periodBone and ulcer samples were sent to the microbiological and pathological anatomy laboratories in all cases, with positive results for osteomyelitis in 70% of them (7 cases). These results (Table 3) were assessed by the infectious diseases service, with prescription of specific antibiotics for at least 6 weeks, whilst in the cases which tested negative for osteomyelitis (3 cases) antibiotic therapy was withdrawn 5 days after surgery.

Series of cases treated with single stage surgery with circular fixation.

| Px | Age (years) | Sex | Side | Eichenholtz | Brodsky | Ulcer | Suspicion of osteomyelitis | Stability | Months of follow-up | Result of intraoperative bone biopsy | External fixation time | Ulcer cure | Plantigrade and stable foot | Clinical symptoms or imaging of osteomyelitis in postoperative period | Complication | Amputation | Reulceration during follow-up period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 64 | M | L | III | Midfoot | Lateral plantar | Yes | No | 24 | Escherichia coli Staphylococcus aureus | 8 weeks | Yes | Yes | No | Superficial infection pin/pin rupture | No | – |

| 2 | 71 | F | R | III | Ankle | Lateral Malleolus | Yes | No | 24 | S. agalactiae/S. aureus MR | 12 weeks | Yes | Yes | No | – | No | – |

| 3 | 39 | M | L | III | Midfoot | Lateral Plantar | Yes | Yes | 21 | Staphylococcus lugdunensis Streptococcus pyogenes Streptococcus agalactiae | 11 weeks | Yes | Yes | No | – | No | – |

| 4 | 71 | F | R | III | Midfoot | Plantar lateral | Yes | Yes | 17 | Staphylococcus epidermidis | 13 weeks | Yes | Yes | No | Superficial infection pin/pin rupture | No | – |

| 5 | 56 | M | R | III | Midfoot | Lateral plantar | Yes | No | 15 | Proteus mirabilis | 10 weeks | Yes | Yes | No | – | No | – |

| 6 | 63 | M | L | III | Ankle | No | No | No | 15 | Negative | 13 weeks | – | Yes | No | Superficial infection pin/tibial fracture | No | – |

| 7 | 55 | F | L | III | Hindfoot | Lateral malleolus | Yes | No | 15 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 13 weeks | Yes | Yes | No | – | No | – |

| 8 | 66 | M | D | III | Midfoot | Lateral plantar | Yes | No | 15 | Negative | 13 weeks | Yes | Yes | No | Superficial infection pin | No | – |

| 9 | 40 | M | L | III | Midfoot | Lateral plantar | Yes | Yes | 12 | Proteus mirabilis Arthrobacter cumminsii Corynebacterium striatum | 13 weeks | Yes | Yes | No | – | No | – |

| 10 | 59 | M | L | III | Ankle | No | No | No | 11 | Negative | 12 weeks | – | Yes | No | – | No | – |

The external fixator was removed after an average of 12 weeks.8–13

The patients began with partial weight-bearing of approximately 50% of their weight with the help of 2 crutches, after 48–72h (Fig. 6). The fixator was removed between 8 and 14 weeks depending on clinical and radiographic assessment. Criteria for removal were medical (reduction of oedema and curing of ulcers) and radiographic (signs of the beginning of consolidation or image indicative of fibrous union).

Later, we used a total contact cast for 4 weeks, followed by a walker type boot, and then footwear adapted for diabetic patients when the swelling had gone down.

Monthly outpatient check-ups were carried out for the first 6 months. After this, they were every 6 weeks until a year of follow-up was complete. The patients were then controlled by health personnel trained in diabetic foot (nurse, podologist, etc.).

Due to the actual patient characteristics, standard functional scales did not offer the relevant information. Patients were asked about their satisfaction with the outcome and if they were willing to be operated on with the same technique on the contralateral foot, if necessary.

Results100% of the patients were able to preserve their lower extremity, achieved a functional planigrade foot, with curing of the skin ulcer and the osteomyelitis, correction of the deformity and recovery of ambulation without any reulceration.

All patients would choose to have the same treatment and would recommend it to a friend.

In 4 cases there were mild complications from superficial infection at the pin insertion site, and these were resolved with local care. A wire also broke in 2 patient but did not require replacing.

One patient presented with a tibial fracture after the removal of the total contact cast in their home and due to complete load bearing with posterior casual fall and trauma in the leg. The fracture was at the level of one of the fixator pin tracts. The fracture was resolved by orthopaedic treatment.

DiscussionCharcot foot is a complex disease due to the combination of bone and soft tissue injuries but also because of the pathophysiological changes of the diabetic patient. Treatment objectives are to avoid amputation and achieve a functional limb with no cutaneous ulcers or osteomyelitis.

Pinzur et al.21 described their series of 178 patients for whom single stage surgery with static circular fixation was applied with a follow-up of 78 months, thus achieving an extremity salvage rate of 95.7% and ambulation in commercial footwear of these patients, with only 3 amputations.21

In 2009, Dalla Paola et al.23 presented the results of their series of 45 patients with Charcot foot associated with osteomyelitis treated with external fixation. They cured 39 of them with the fixator being maintained for an average of 26 weeks.23

Cooper25 described a retrospective series of 100 Charcot feet treated with static circular fixation over a period of 4 years. 80% of the patients presented with an ulcer when surgery was performed, and had an average age of 56 years. They achieved a salvage rate of 96%, with a follow-up of 22 months. They referred to complications as superficial infection at pin entry (7 patients), tibia fracture (2) and repeated ulcerations (4).25

Some publications have suggested Charcot foot treatment with hybrid external fixation systems using transfixion wires and standard monolateral fixators.26 Its drawback is the risk of fracture in the insertion area of the standard thick fixator pins. Jones27 described this complication in his retrospective series of 245 patients treated with this system, obtaining fractures of this type in 10 patients, and for which its use was not recommended. In our series we observed one tibia fracture despite not having used thick pins. The osteoporosis which was present together with trauma produced by a fall and the creation of a weak bony point in the pin tract could have impacted in this fracture.

Rogers et al.28 state that complications of the use of the static circular fixation system are usually frequent but of little clinical relevance. The most common, with prevalence of between 10% and 20% is superficial infection of the skin around the entry and exit of the transfixion wires which is satisfactorily resolved with local would care and oral antibiotics. In our series management and prognosis of superficial infection at this level was no different from that published in the literature.21,28

Other complications related to ischaemia time are compressive neurapraxia, deep vein thrombosis, skin necrosis and surgical wound infection,28,29 although none of these presented in our series.

In some patients, standard techniques of internal fixation could fail due to the poor secondary bone quality from low level vitamin D osteoporosis which characterises them.19 The latter is associated with pseudoarthrosis of these patients and results in osteosynthesis material being submitted to continuous mechanical stress with a high risk of rupture and surgical failure.19

Results from our series with regard to extremity salvage rates, cure of plantar ulcers, correction of deformity, eradication of osteomyelities and absence of repeated injury coincide with those obtained by these authors.21,23,25 This confirms that despite our short series, treatment with a static circular fixator could be reproducible in our environment.

One of the weaknesses of our study was that it was retrospective, with few patients, which is explained by the low prevalence of this pathology. Also, there was no control group, which is ethically difficult to reconcile with our series. We would therefore encourage further prospective, multicentre studies with a larger patient sample and a comparison of the different possible fixation techniques in these patients.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rios Ruh JM, López Capdevila L, Domínguez Sevilla A, Roman Verdasco J, Santamaría Fumas A, Sales Pérez JM. Tratamiento del pie de Charcot complejo mediante cirugía en un solo tiempo con fijador circular estático. Serie de casos. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol. 2019;63:41–48.