Avian aspergillosis is mainly a respiratory disease that affects all types of birds and is mostly caused by Aspergillus fumigatus. Factors such as the abundant presence of conidia in the environment, the impairment of the immune system due to stress or other causes, and the special respiratory tract of birds, make these animals more susceptible to infection by this species.

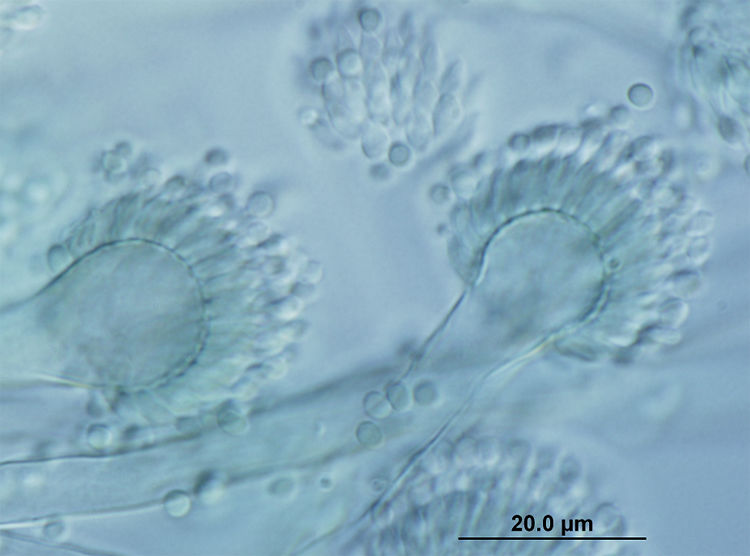

In poultry farming, intensive production systems may facilitate some of these situations if management and hygiene conditions are not suitable. Egg incubation chambers, hatching rooms and the quality of the poultry litter are critical. In these facilities a high amount of A. fumigatus conidia can accumulate. These spores are among the smallest that can be found among the Aspergillus species, with a size of 2–3μm in diameter (Fig. 1).

One of the main routes of entry of conidia into hatcheries is through contaminated eggs. The spores present on the shell can penetrate the egg through small cracks and find the optimal culture conditions to produce millions of new conidia in few hours. A. fumigatus conidia remain in the environment and can rapidly increase in a wide range of conditions, but especially in organic matter such as egg yolk, cardboard boxes, sawdust and wood shavings, chopped straw and feed residues, which can be found in various rooms used in poultry production. In addition, the high humidity and temperature conditions (37–45°C) in these facilities favour the growth of this thermophilic species.

Chicks inhale these spores, which due to their small size easily reach the lungs and air sacs causing the acute form of the disease. This form is responsible for the increased mortality seen in the first few days of the chick's life. In infected birds, the air sacs and lungs usually show white or yellowish nodules and even greenish fungal plaques characteristic of this species (Fig. 2). Subacute and chronic forms are detected in older birds and the infection may even spread to other organs.

In contrast to isolates from other animals or humans, only A. fumigatus sensu stricto strains within the Fumigati section are isolated from poultry and poultry production facilities.1 Although there are not many studies on this subject in poultry, no cryptic species close to A. fumigatus have been detected.

In a study of 175 strains mostly isolated from poultry in France and China, all were identified as A. fumigatus.3 None of the strains studied were considered resistant to itraconazole. Although treatment with antifungal agents is not usually administered in these production systems, certain non-triazole antifungals can be used for the disinfection of the facilities and the prevention of some mycoses (e.g. enilconazole, thiabendazole, parconazole). Therefore, it is important to know the potential risk of emergence of resistant strains related to poultry production, since antifungal resistance in A. fumigatus strains of clinical and environmental origin is an emerging problem.

Several triazole antifungals (e.g. itraconazole, voriconazole) are recommended as drugs of choice in the treatment and prophylaxis of aspergillosis in humans, being the main factor in the selection of resistant strains in A. fumigatus. However, numerous resistant strains of this species have also been associated with the massive use of various triazole fungicides in agriculture to prevent and control different diseases in cereals, fruits, legumes and ornamental plants.2 We do not know whether this will end up happening in poultry farms where A. fumigatus is the most prevalent species.

Conflict of interestAuthor has no conflict of interest.

Financial support came from Servei Veterinari de Bacteriologia i Micologia of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

These Mycology Forum articles can be consulted in Spanish on the Animal Mycology section on the website of the Spanish Mycology Association (https://aemicol.com/micologia-animal/).