The relationship between lobomycosis and paracoccidioidomycosis goes back a long way. Jorge Lobo reported in 1931 the observation of an unusual yeast-like fungal pathogen in a human patient with skin lesions, and described this disease as a mild variety of paracoccidioidomycosis. Over the years, the disease has received various names, such as Lobos’ disease, lobomycosis and, more recently, lacaziosis. Attempts to isolate the fungus from the skin lesions failed. Many years later, a similar skin disease was reported in dolphins, and based on its phenotypic features in the infected tissues and its non-culturable condition, the etiological agent was thought to be the same as that described in humans. Thereafter, this mycosis in humans was found restricted to Latin American countries, mainly in the Amazon basin. In dolphins, it has been described in specimens from several oceans, mostly in coastal areas of the Americas and Japan.

As it is a non-culturable fungus, its nomenclature has always been controversial and this causative agent has been known under various names, such as Paracocciodioides loboi or Loboa loboi, and, more recently, Lacazia loboi. After 90 years of taxonomic uncertainties, using phenotypic, phylogenetic, and population genetics analyses, the two non-culturable fungi which cause this skin disease in humans and dolphins are now, once again, placed as separate species within the genus Paracoccidioides.3 These authors have proposed the names Paracoccidioides cetii for the species that causes the disease in dolphins and P. loboi for the one that causes the disease in human beings.

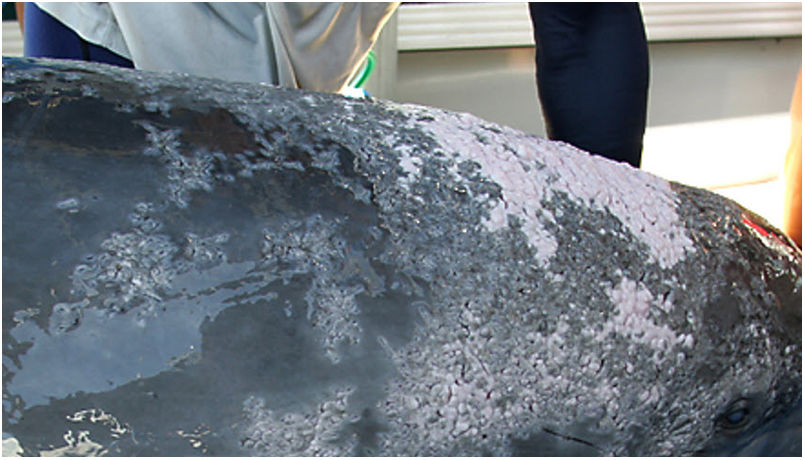

Most lobomycosis-like cases in cetaceans have been described in free-ranging bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and in very few specimens among other species such as Tursiops aduncus, Lagenorhynchus obliquidens, Sotalia guianensis, Sousa plumbea and Stenella frontalis. A Pubmed search using the descriptors “lobomycosis” AND “dolphins” (December 15th, 2021) yielded a total of 33 case reports regarding lobomycosis in different dolphin species. Bottlenose dolphins appeared in 76 percent of these papers. However, in several cases, the diagnosis of lobomycosis was made only through photo-identification. In general, lesions are verrucous and form crusty plaques with ulcerations that are limited to the skin (Fig. 1).

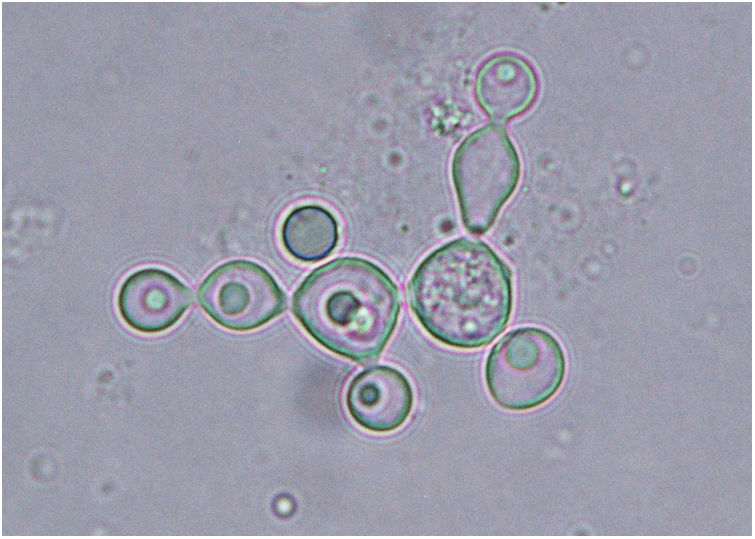

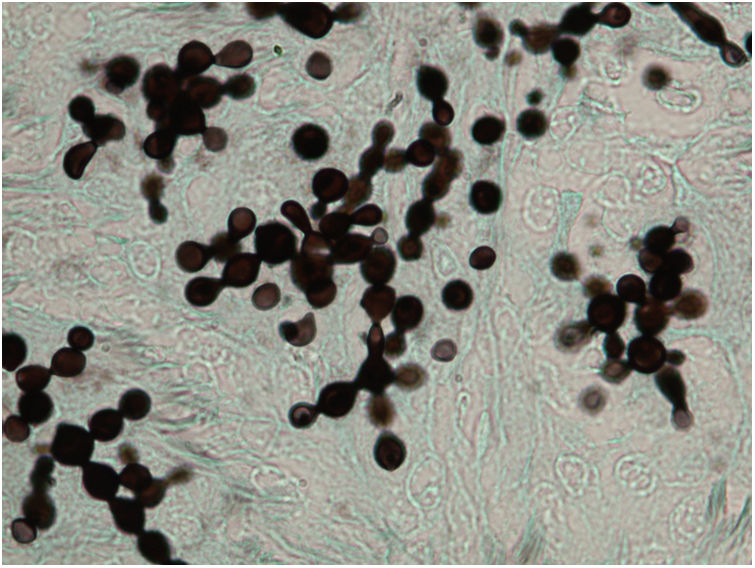

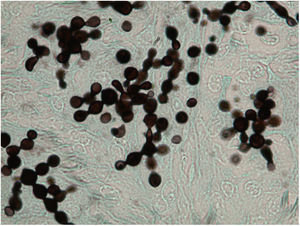

However, this disease has also been diagnosed in dolphins in captivity far from the coastal areas where lobomycosis is distributed. This is the case of a bottlenose dolphin born in the wild who was brought from Cuba to an aquarium in Spain.1 This animal arrived with two localized, slightly prominent, whitish dermal lesions on the left flipper. Cytology and histopathology analyses of the skin lesions showed the presence of yeast-like structures in chains, characteristic of lobomycosis (Figs. 2 and 3). Interestingly, the animal was treated along several phases using mainly itraconazole and terbinafine and, after four weeks, the lesions were reduced to single, small, cicatricial nodules. Usually, these animals are not treated so there is little information about the treatment of this mycosis.

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a systemic fungal infection occurring in Latin America caused by culturable fungi of the genus Paracoccidioides, whose major known hosts are humans and armadillos. Paracoccidioides brasiliensis has been considered for many years the only species causing this disease. Nowadays it is known that, at least, five phylogenetic species may cause this disease: Paracoccidioides americana, P. brasiliensis sensu stricto, Paracoccidioides lutzii, Paracoccidioides restrepiensis and Paracoccidioides venezuelensis. Although Paracoccidioides spp. ecological niche has not yet been precisely identified, this pathogen has been mainly associated with nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus) and their burrows. The infection occurs by inhaling fungal propagules dispersed in the air after soil disturbing activities. The human disease may develop acutely, which is rare but, usually, more severe, and chronically, after a long latency period, years or even decades. Wild animals infected with P. brasiliensis can be important sentinels regarding the presence of this fungus in the environment. The detection of this pathogen in road-killed wild animals has been proven a key strategy for eco-epidemiological surveillance of paracoccidioidomycosis, helping to map hot spots for human infection. Recently, following this approach, two new hosts for this fungal pathogen have been cited, the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyonthous) and the paca (Cuniculus paca).2

As far as the lobomycosis is concerned, although a possible zoonotic transmission has been raised due to the similarity of both lesions and disease agents in humans and dolphins, there are no conclusive data pointing out that these cetaceans infected with P. cetii can transmit the disease to humans.

Conflict of interestAuthor has no conflict of interest.

Financial support came from Servei Veterinari de Bacteriologia i Micologia of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

These Mycology Forum articles can be consulted in Spanish on the Animal Mycology section on the website of the Spanish Mycology Association (https://aemicol.com/micologia-animal/).