Depression is not uncommon among infertile couples. The objective of the study is to analyze factors that predict depression in these couples, when they are in Assisted Reproduction Techniques programs.

Materials and methodWe analyze the level of depression in couples referred from the Human Reproduction Unit to study the male factor using the Beck Depression Inventory and the clinical information contained in the SARAplus program.

ResultsDepressive ranges appear in approximately half of the participants. The degree of depression correlates in a statistically significant way between both members of the couple. Among the analyzed clinical factors, we observed relational tendency between depression and obesity and depression and smoking.

ConclusionsDepression in infertile couples is a fact. ART specialists should be on the lookout for symptoms of depression in order to provide patients psychological and psychiatric care and treatments, as part of the overall therapeutic framework for infertility.

Infertility is defined as the absence of conception after 12 months of regular, unprotected coitus.1 Infertility affects approximately 15% of couples. About one-third of cases are due to a female factor, one-third are due to a male factor, and another third is a mixed type. Remaining 5% for unexplained causes.2 In this situation, many couples look for a solution to the problem asking for help from reproduction professionals.3–5

Infertility is mainly caused by the delay in the woman's procreative age and the decrease in the quality of semen in men (low concentration of spermatozoa, low percentage of mobility and higher percentage of anomalous morphology).3

In Spain there is no legal age limit to apply for ART.6 However, the Spanish Fertility Society discourages ART on women over 50 years of age. The National Health System establishes a limit of 40 years for women and 55 years for men.7

Some studies have shown the influence of stress and emotions on a biological level, even frustration per se can deteriorate fertility status.8–12 The high levels of anxiety generated by the diagnostic-therapeutic process of infertility can cause moderate depression up to 19% of couples and severe depression to 13%.13 Negative feelings can self-revert in anxiety, depression and impotence.14 Therefore, psychosocial attention is important in the treatment of infertility, but paradoxically it is unusual in the reproductive clinic.13,14 As a result, the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) published a manual entitled “Routine psychosocial care in infertility and medically assisted reproduction”.15

About 23% of couples prematurely discontinue ART treatment as a result of the perceived emotional burden,16 a third of patients complete treatment with no successful pregnancy17 and couples with a previous history of depression present a high risk of relapse.17,18 In the same vein, our group has also found a relation between ART and depression.19–22

In view of the above, two issues are of relevance: (a) infertility and ART produce stress, anxiety, depression and worsening sexual response and (b) the available data do not provide sufficient evidence on these issues, which clearly reinforces the need to study the psychological and sexual response of couples submitted to ART, observing the interconnections between Biology, Medicine and Psychology, with the practical clinical objective of improving the treatment of couples in ART and their reproductive outcomes.

MethodSampleThe sample is made up of 99 heterosexual couples referred to the Andrology-Sexual and Reproductive Medicine Unit from the Human Reproduction Unit of the University Hospital Complex of the Canary Islands. Between February 2015 and June 2017 we attend 99 men with pathological reproductive factor, defined as at least two consecutive altered seminograms,1 along with their corresponding 99 women. Men's age ranged from 25 to 56 years (=38.2±6.38) and women's between 22 and 42 years (=34.37±4.71). The average time of infertility varied between 1 and 8 years (=2.52±1.43).

InstrumentsThe Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)23 was initially developed as a heteroaplicated scale of 21 items to assess the severity (symptomatic intensity) of depression; however, its subsequent use has become widespread as a self-applied scale. Beck et al.24 present a new revised version (first release) of their inventory, adapted and translated into Spanish by Sanz and Vázquez.25

This self-applied 21-item questionnaire evaluates a broad spectrum of depressive symptoms. Four response alternatives (0–3) are systematized for each item, which evaluate the severity/intensity of the symptom. The time frame refers to the current moment and the previous week. The total score is obtained by adding the values of the answers (max=63). The cut-off points for the first release usually accepted for grading intensity/severity are as follows: no depression: 0–9 points; mild depression: 10–18 points; moderate depression: 19–29 points; severe depression: more than 30 points. Its psychometric indices have been studied exhaustively, showing a good internal consistency (Cronbach alpha 0.76–0.95).25

We include an additional category of “Subclinical Depression” for values between 6 and 9, based on to the definition of Judd et al., referred by Rivas et al.,26 “two or more simultaneous symptoms of depression, present most of the time, at least for two weeks, associated with evidence of social dysfunction, in an individual who does not meet criteria for the diagnosis of minor depression, major and/or distinct depression”.

Information has also been collected on weight, smoking and the existence of urological or gynaecological disorders.

ProcedureCouples who come for an Andrology appointment undergo a clinical review in which the possible causes of infertility are studied. A clinical history (SARAplus, version 1.5.35249, Merck Serono) is made and they are asked to collaborate in this research. Once both members of the couple were informed of the intent of this study, their verbal consent was requested. Subsequently, both partners completed the BDI independently and without interference.

Ethic statementAll procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments o comparable ethical standards and has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the CHUC.

Data analysisThe obtained data were subjected to descriptive analysis, Pearson's correlations, t-tests and Chi-square tests. In all tests the level of significance was set at 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM© SPSS Statistics, v.21.0. (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

ResultsIn our series, the average time of infertility is 2.52 (±1.43) years. More than half of couples (55.9%) start ART protocol in the first 2 years of infertility. Only 1.9% come with more than five years of reproductive problems. Both members of couples had mainly primary sterility (84.2%), and only 2.1% had secondary sterility. The combination of primary sterility in women and secondary sterility in men is more frequent (9.5%) than the opposite case (4.2%).

In relation to depression, men present an average score lower than 6 in the BDI (=5.79±6.76) and women somewhat higher (=6.85±7.02). This difference is not significant (t193=1.07; p=0.284). The correlation of the depression total BDI score of men with that of their women (r=.49; p=.000) is significant, sharing 23.52% of its variability.

Regarding the categorized ranges of depression, we observe that slightly more than half of the women (54.6%) are found in one of the ranges of depression (subclinical, mild, moderate or severe): 25.8% (n=25) subclinical depression; 24.7% (n=24) mild depression, 2.1% (n=2) moderate depression and 2.1% (n=2) severe depression. In contrast, slightly less than half of males were found in one of the ranges of depression (43.9%): 24.5% (n=24) subclinical depression; 14.3% (n=14) mild depression; 3.1% (n=3) moderate depression and 2.0% (n=2) severe depression. Unfortunately there were three missing cases (two women and one man from different couples) in relation to the measure of depression. Given the lack of cases involving moderate or severe depressions, it was decided to regroup the latter together with mild depression (Table 1). The distribution of depressive ranges does not depend on sex (χ22=4.07;p=.397).

Depressive ranges according to sex (% by row and n).

| Gender | No depression | Subclinical depression | Depression* | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 56.1% (55) | 24.5% (24) | 19.4% (19) | 100% (98) |

| Female | 45.4% (44) | 25.8% (25) | 28.9% (28) | 100% (97) |

| Total | 50.8% (99) | 25.1% (49) | 24.1% (47) | 100% (195) |

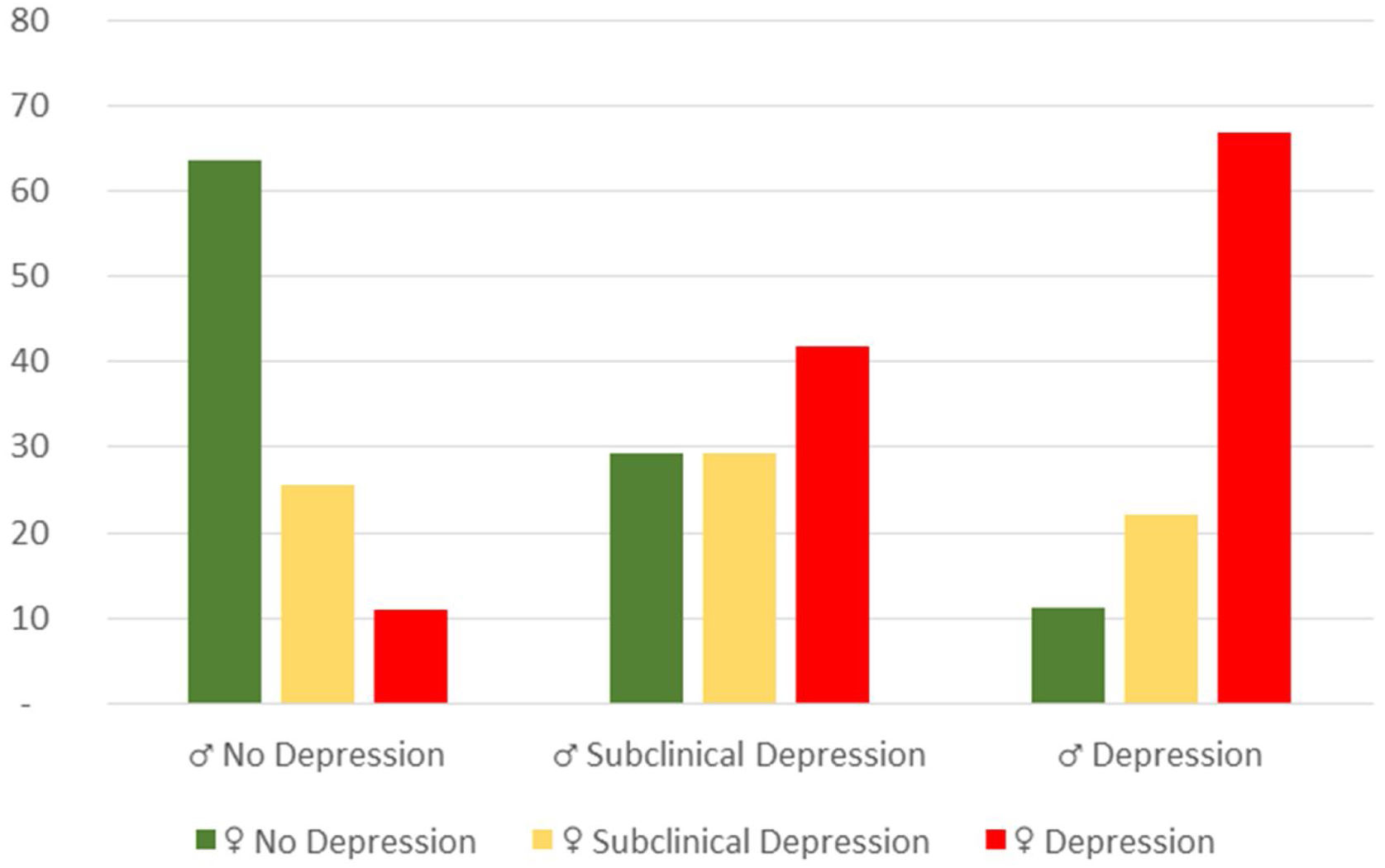

Fig. 1 shows the combination of a man's depressive category with his partner's category. In Table 2 we can observe that in case the male is not depressed, in 63.6% his partner is not depressed either.

Depressive range of women combined with depressive ranges of their men (% per row).

When the male is in the subclinical depressive category, his partner is also subclinical depressive at 29.2% or even in a mild/moderate/severe depressive range at 41.7%. When the male is depressed, his partner is mostly in a depressed range (66.7%) or subclinical range (22.2%). That is, the mood in the couples is related in both members of the couple (χ42=26.71;p=.000), according to the above obtained relation for total scores.

When linking depression with categorized weight (normal BMI: <25; overweight: 25≤BMI<30), there is no significant relation, although there is a trend towards a higher percentage of depression among overweighed men (χ22=1.33;p=.513) and a contrary trend in women (χ22=3.44;p=.179). 14.1% of men and 24.2% of women were overweighted.

Relating ranges of depression to smoking, also there is a tendency, although not significant, to a higher percentage of depression among smokers, both in men (χ22=44.52;p=.104) and in women (χ22=3.21;p=.201). 28.3% of men and 26.3% were smoker.

Concerning urological and gynaecological alterations, more than half of the men (59.6%) have no urological alterations and approximately half of the women (51.5%) have no gynaecological alterations (Table 3). However, the distribution of depression categories among men does not depend on urological alterations (χ22=.10;p=.953), nor among women on gynaecological alterations (χ22=.03;p=.985).

Men's depressive ranges as a function of urological or gynaecological alterations.

| No depression | Subclinical depression | Depression* | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | ||||

| No alteration | 55.9% (33) | 25.4% (15) | 18.6% (11) | 100.0% (59) |

| Alteration | 56.4% (22) | 23.1% (9) | 20.5% (8) | 100.0% (39) |

| Total | 56.1% (55) | 24.5% (24) | 19.4% (19) | 100.0% (98) |

| Females | ||||

| No alteration | 44.9% (22) | 26.5% (13) | 28.6% (14) | 100.0% (49) |

| Alteration | 45.8% (22) | 25.0% (12) | 29.2% (14) | 100.0% (48) |

| Total | 45.4% (44) | 25.8% (25) | 28.9% (28) | 100.0% (97) |

As for the mean age of women in ART protocol, according to the Spanish Registry of Assisted Reproduction Techniques of the Spanish Fertility Society (SEF) for 2004, more than 54% of patients were over 35 years of age.3 By 2017, they have risen to 70% (46% between 35 and 39 and 24% 40 or more years).27 Simultaneously, Khademi et al. (Iran 2005) observed a mean of 29 years among women (28.9±5.5).28 Peterson et al. (USA 2014) report a mean age of 32 (31.9±3.6).11 In the present study (Spain 2017) we obtained a mean of 34 years (34.37±4.7), similar to the data presented by the SEF.

Regarding the mean age of males in the TRA protocol, Ahmadi et al. (2011), describe a mean age of 34 years (34.1±7.1).29 Peterson et al.11 (2014) also observe a mean age of 34 years (34.3±5.1). Ozkan et al.30 (2015) also 34 years (33.9±5.1). In our study (2017) we found a higher mean compared to these authors (38.2±6.4), as well as in the women case.

We realize that there are differences between the ages among the different studies, probably as a consequence of chronological, geographical and cultural differences.

In the present study, the mean duration of infertilities found was two and a half years (2.52±1.4), contrary to what was described in the study by Peterson et al.,11 where couples had suffered infertility for four years (4.2±2.3). This duration increases to seven years (7±6) for Ahmadi et al.,29 resulting a significant parameter in relation to depression. According to the references, there seems to be a tendency to reduce the time for consultation in assisted reproduction units, probably as a consequence of the evolution of this medical field.

Men and women respond differently to the diagnosis of infertility. We observe that women are in one of the categories of depression (subclinical, mild, moderate or severe) in slightly more than half of the cases (54.7%). However, in men the percentage is lower (43%). The degree of depression, measured by BDI, correlates positively between both partners.

Our data, when incorporating the category of subclinical depression (BDI>5), may surpass those found in other studies, which do not consider this state of mind.13 For Khademi et al., following the BDI ranges, 31% of women suffer mild depression (score from 16 to 31) and only 8% had moderate (≥19) or severe symptoms (≥32).28 Ahmadi et al. included 42.9% of men in depression categories (BDI≥17).29 These percentages are similar to those found by us, despite the ethnic, cultural and geographical difference, as well as the difference in BDI score and degree of depression.

We consider the contribution of Khademi et al. interesting; they found statistically significant differences in the BDI between the start of treatment vs. the end. The mean BDI score rose after unsuccessful treatment and dropped after successful treatment.28 Consequently, it would be relevant to monitor depression in order to assess its status in couples undergoing ART at different stages, type of treatment and outcome (pregnancy).

As for non-specific variables, we observed a relational tendency between depression and overweight, without being able to demonstrate it in a statistically significant way. On one hand, among women, Volgsten et al.10 referred that obese women had an increased risk of developing depression during the treatment. On the Contrary, our results let see that there is a trend to overweighed women had minor depression risk than normal weighted. This could be because in our sample, due to the norms of the National Health System, obese women (BMI>30) should not be treated before they reach a BMI<30. On the other hand, among males, it has been proposed that obesity affects male fertility both directly and indirectly, inducing alterations in sexual behaviour, hormonal profiles, scrotal temperature and seminal parameters. Also a higher incidence of obesity has been described for men in need of infertility treatment.31 This fact could be related to Volgsten et al. finding of lower testosterone levels in men undergoing infertility treatment.10 In the same way, we found that overweighed men had higher risk for depression.

Concerning smoking, various studies have shown that smokers, in general, are more likely to be in depressive episodes compared to non-smokers.32 In the same vein, Ahmadi et al. found that 19.3% of men were smokers at the time of treatment. Smoking was found to significantly affect mood.29 In our study, the percentage of men and women who smoked is similar (28.7% vs. 27.2%), finding no significant relationship with depression status, although there is a tendency towards higher levels of depression among smokers.

At the present time, the knowledge acquired through various investigations leads us to think that doctors in the reproductive area should be alert to the detection, among infertile men and women, of symptoms of undetected depression in order to provide them psychological and psychiatric care and treatments, as part of the overall therapeutic framework for infertility.

As we have focused only on couples with a pathological male factor, future studies should include couples of all kinds and perform follow-up studies, not only relating depression with demographic variables, but also with successful or failed pregnancy by ART.

Authors’ contributionsAntonia María Salazar Mederos: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data. (2) Drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published.

Pedro Ramón Gutiérrez Hernández: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, interpretation of data. (2) Drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published.

Yanira Ortega González: (1) substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data. (2) Drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published.

Stephany Hess Medler: (1) substantial contributions to analysis and interpretation of data. (2) Drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content. (3) Final approval of the version to be published.

Ethical disclosureProtection of people and animalsThe authors state that for this research no experiments have been conducted on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that they have followed their workplace's protocols on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in the possession of the corresponding author.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.