The aim of this study was to determine the levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) patients who attended our clinic.

Materials and methodsA total of 40 male patients were included in the study troubled with non-obstructive azoospermia. An etiological classification was made according to the hormone levels of the patients. The semen specimen was obtained by masturbation from the patients. Three questionnaires, the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Anxiety Inventory, and the Short Form of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire, were utilized in the study.

ResultsThe mean age of the patients in the study was 32.75±5.22 years. The patients were classified as follows: 26 (65%) patients were idiopathic, 11 (27.5%) patients were hyper–hypo and 3 (7.5%) patients could not be reached. In this cohort, 62.5% of patients had minimal depression, 27.5% of patients had mild depression and 10% of patients had moderate depression. In addition, 97.5% of patients had minimal anxiety and 2.5% of the patients had mild anxiety. Quality of life scores of the patients were 58.75% for general health status, 70.98% for physical health status, 72.92% for psychological status, 65% for social relations and 66.25% for environmental status.

ConclusionNOA particularly affects men in terms of biological, psychological and social aspects. In order to evaluate the quality of life and psychiatric conditions patients with azoospermia, various questionnaires may be applied before infertility treatment. Thus, patients who need psychiatric support can be identified.

El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar los niveles de depresión, ansiedad y calidad de vida de los pacientes con azoospermia no obstructiva (ANO) que acudieron a nuestra clínica.

Materiales y métodosUn total de 40 pacientes varones con problemas de azoospermia no obstructiva fueron incluidos en el estudio. Se realizó una clasificación etiológica según los niveles hormonales de los pacientes. La muestra de semen se obtuvo por masturbación de los pacientes. En el estudio se utilizaron 3 cuestionarios: el Inventario de Depresión de Beck, el Inventario de Ansiedad de Beck y la Forma Corta del Cuestionario de Calidad de Vida de la Organización Mundial de la Salud.

ResultadosLa edad media de los pacientes en el estudio fue de 32,75±5,22 años. Los pacientes se clasificaron de la siguiente manera: 26 (65%) pacientes eran idiopáticos, 11 (27,5%) pacientes eran hiperhipóficos y 3 (7,5%) pacientes no pudieron ser alcanzados. En esta cohorte, el 62,5% de los pacientes tenía depresión mínima, el 27,5% de los pacientes tenía depresión leve y el 10% de los pacientes tenía depresión moderada. Además, el 97,5% de los pacientes tenían ansiedad mínima y el 2,5% de los pacientes tenía ansiedad leve. Las puntuaciones de calidad de vida de los pacientes fueron del 58,75% para el estado de salud general, del 70,98% para el estado de salud física, del 72,92% para el estado psicológico, del 65% para las relaciones sociales y del 66,25% para el estado ambiental.

ConclusiónLa ANO está afectando particularmente a los varones en términos de aspectos biológicos, psicológicos y sociales. Para evaluar la calidad de vida y las condiciones psiquiátricas de los pacientes con azoospermia, se pueden aplicar varios cuestionarios antes del tratamiento de la infertilidad. Por lo tanto, pueden identificarse los pacientes que necesitan apoyo psiquiátrico.

Infertility is the inability to reach a pregnancy despite of one year unprotected sexual intercourse.1 Approximately 15% of couples do not reach pregnancy in one year and apply for medical treatment for infertility.2,3 The male factor is responsible for nearly half of infertility cases. Sperm analysis is the main step in the evaluation of male infertility and the sperm concentration is expected to be at least 15 million per milliliter in a normal semen.4 The absence of spermatozoa in semen analysis is defined as azoospermia. Obstructive azoospermia (OA) is the absence of sperm in semen analysis or post ejaculatory urine analysis due to obstruction. Non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA), that is more common than OA, is detected in approximately 10% of all infertile men.5 NOA refers to spermatogenesis disorder. Despite numerous studies in this field, unfortunately the sperm retrieval outcomes by microdissection testicular sperm extraction (m-TESE) in patients with NOA do not exceed the rate of 50%.5 Even if a sperm obtained by m-TESE, it is not certain that pregnancy will occur.

Although infertility is seen as a physical problem, it has also biological, social, cultural, psychological and economic aspects.6,7 Infertility may cause frustration, mental symptoms, a sense of guilt, and a mutual blame between couples. People who cannot have children can see themselves as inadequate about reproduction. Male and female partners may show different emotional reactions in case of infertility. It is reported that women experience more stress than men in case of having infertility.8 There are publications showing that psychological problems, especially anxiety and depression, are more common in infertile men than fertile men.9–11 Many factors can be responsible for the results, such as uncertainty in the etiology of infertility, uncertainty of treatment period, negative outcomes of treatment, economic burden of treatment, and community pressure. It is very important that a man to have a child in Middle Eastern countries.12 In these societies, it is argued that the virility of infertile men is discussed and a serious stress is created on them.

NOA is one of the causes of male infertility which is difficult to treat. In recent years, NOA has become increasingly widespread and it has turned into a life crisis for couples. Therefore, we think that psychiatric symptoms should be defined in NOA patients. Psychological counseling, psychosocial support or medical treatment may be required for this group.

In fact there are several studies that examine the relationship between male infertility and mental status.3,9,11,13 Infertile males were evaluated according to sperm quality in only a part of these publications but azoospermic patients were not mentioned. Since azoospermia is a spermatogenesis disorder, it can be very difficult to obtain sperm, so these people may not have children throughout their lives. Therefore, mental disorders can be seen more frequently in these patients. The aim of this study was to determine the levels of depression, anxiety and quality of life in NOA patients who applied to our clinic.

Materials and methodsParticipants and study designFourty male patients who troubled from NOA and applied to our fertility clinic from January 2018 to March 2019 were collected to the study. The selection criteria for the study were as follows: (a) not being able to have a baby due to azoospermia; (b) female reproductive systems to be healthy; (c) at least 18 years old; (d) had no mental illness or psychiatric disorders; (e) ability to read and write in Turkish.

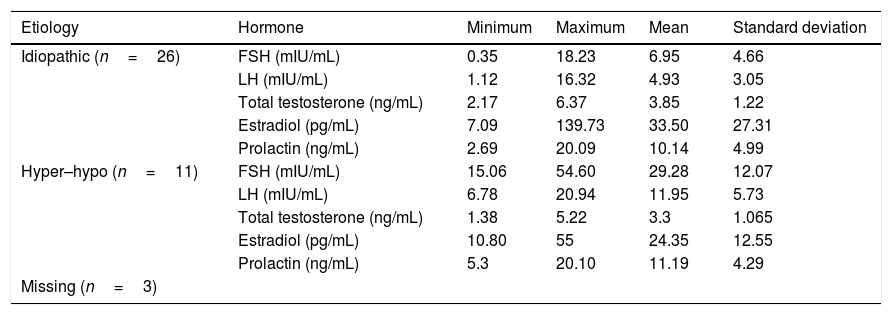

A thorough urogenital examination (secondary sex characteristics, testicular size, presence of vas deferens, presence of varicocele) was performed by a urologist to the all patients. After the physical examination, all patients were evaluated by serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), total testosterone (TT), estradiol (E) and prolactin (P). An etiologic classification was made according to the hormone levels of the patients. In this infertility classification, patients were recorded as hypergonadotropic hypogonadism (hyper–hypo), hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (hypo–hypo) or idiopathic. The patients with normal hormone levels were evaluated in the idiopathic infertility group.

The semen specimen was obtained by masturbation from the patients. At least two semen specimens were collected from each patient for the diagnosis of azoospermia. The diagnosis of azoospermia was determined according to the WHO laboratory guide.4

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Gülhane Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey. Oral and written informed consent was obtained by a physician from all patients.

QuestionnairesThree questionnaires, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and the Short Form of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire, were utilized in the study. All patients filled out the questionnaires in a quiet place. BDI and BAI are characterized by high validity, credibility, reliability and test–retest reliability with regard to isolation of patient symptoms.7,9,11,14–17 Sociodemographic data were gathered from patients including age of couples, duration of infertility, educational status, smoking, chronic diseases, failure of previous male infertility treatment.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)The BDI was developed by Beck et al. to measure the behavioral findings of depression in adolescents and adults.18 It is a self-assessment scale for general and psychiatric population.19 Its aim is to determine the risk for depression and to measure the level of depressive symptoms and the severity of depression. This form, which includes a total of 21 self-assessment measures, provides a 4-point Likert-type scale. Depression-specific behaviors and symptoms are defined by a series of sentences and each sentence is numbered as 0–3 point. Total points are obtained by collecting them. The high total score indicates the severity of depression. The Turkish reliability and validity assessment was performed previously and the cut-off score was determined as 17 points for clinically significant depression.20 According to the BDI, the classification of depression was expressed as follows: 0–9, minimal; 10–18, mild; 19–29, moderate; and 30–63, severe.21 The reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of the scale was determined in this study to be 0.80.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)The BAI was developed by Beck et al. and adapted to Turkish by Ulusoy.22,23 The scale aims to determine the frequency and severity of anxiety symptoms that experience by individuals.9 It provides a Likert-type scale. There are four options in each of twenty-one questions and each item gets a score between 0 and 3. A high total score indicates that the individual's anxiety is severe. According to the BAI, the classification of anxiety was expressed as follows: 0–7, minimal; 8–15, mild; 16–25, moderate; and 26–63, severe.24 The reliability (Cronbach's alpha) of the scale was determined in this study to be 0.90.

Short Form of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (Turkish) (WHOQOL-BREF-TR)The World Health Organization (WHO) has started to define the quality of life in 1980 and has developed the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL)-100 scale which allows cross-cultural comparisons with the contribution of 15 centers from various countries. The Short Form of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL-BREF) is a short form of the WHOQOL-100, it has consists of 5 sub-dimensions. The scale is composed of 26 questions that measure general health, physical, psychological, social and environmental health.25,26 The validity and reliability study of the Turkish version was conducted by Eser et al.27 WHOQOL-BREF-TR is composed of 27 questions by adding a national question during validation studies in Turkish. Each of the questions contains Likert type closed-ended responses and the options are scored between 1 (very poor, very dissatisfied, not at all, never) and 5 (very good, very satisfied, an extreme amount, always).25,26 The scoring system of the scale was defined by the WHO. It can be scored from 0 to 100 points. High scores indicate a better quality of life.27

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences 20.0 software (SPSS 20.0 for MAC). Descriptive statistics were expressed with numbers, percentiles, or mean±standard deviation (minimum–maximum). Shapiro–Wilk, Kurtosis, and Skewness Tests were used to assess the variables’ normalization. Pearson Correlation and Chi Square Test were used to correlate two samples. Probability of p<0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

ResultsA total of 40 male patients were included in the study. The mean age of patients in the study was 32.75±5.22 (range 19–43) years. The mean age of the spouses of the azoospermia patients was 30.4±5.24 (range 20–41) years. The duration of infertility was 29.1±20.96 (range 9–120) months. None of the patients had a child during this study. Patients were categorized according to levels of education as follows: 11 (27.5%) patients graduated from primary–secondary school, 11 (27.5%) patients graduated from high school, 18 (45%) patients graduated from university. The rate of cigarette smoking among NOA patients was 45% (n=18). Five (12.5%) in 40 patients had one chronic illness. Of the patients, 30% (n=12) declared at least one unsuccessful in previous infertility treatment.

The patients were classified as follows: 26 (65%) patients were idiopathic, 11 (27.5%) patients were hyper–hypo and 3 (7.5%) patients could not be reached (Table 1). There were no hypo–hypo patients according to the hormone levels.

Etiological classification of patients according to hormone levels.

| Etiology | Hormone | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic (n=26) | FSH (mIU/mL) | 0.35 | 18.23 | 6.95 | 4.66 |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 1.12 | 16.32 | 4.93 | 3.05 | |

| Total testosterone (ng/mL) | 2.17 | 6.37 | 3.85 | 1.22 | |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 7.09 | 139.73 | 33.50 | 27.31 | |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 2.69 | 20.09 | 10.14 | 4.99 | |

| Hyper–hypo (n=11) | FSH (mIU/mL) | 15.06 | 54.60 | 29.28 | 12.07 |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 6.78 | 20.94 | 11.95 | 5.73 | |

| Total testosterone (ng/mL) | 1.38 | 5.22 | 3.3 | 1.065 | |

| Estradiol (pg/mL) | 10.80 | 55 | 24.35 | 12.55 | |

| Prolactin (ng/mL) | 5.3 | 20.10 | 11.19 | 4.29 | |

| Missing (n=3) |

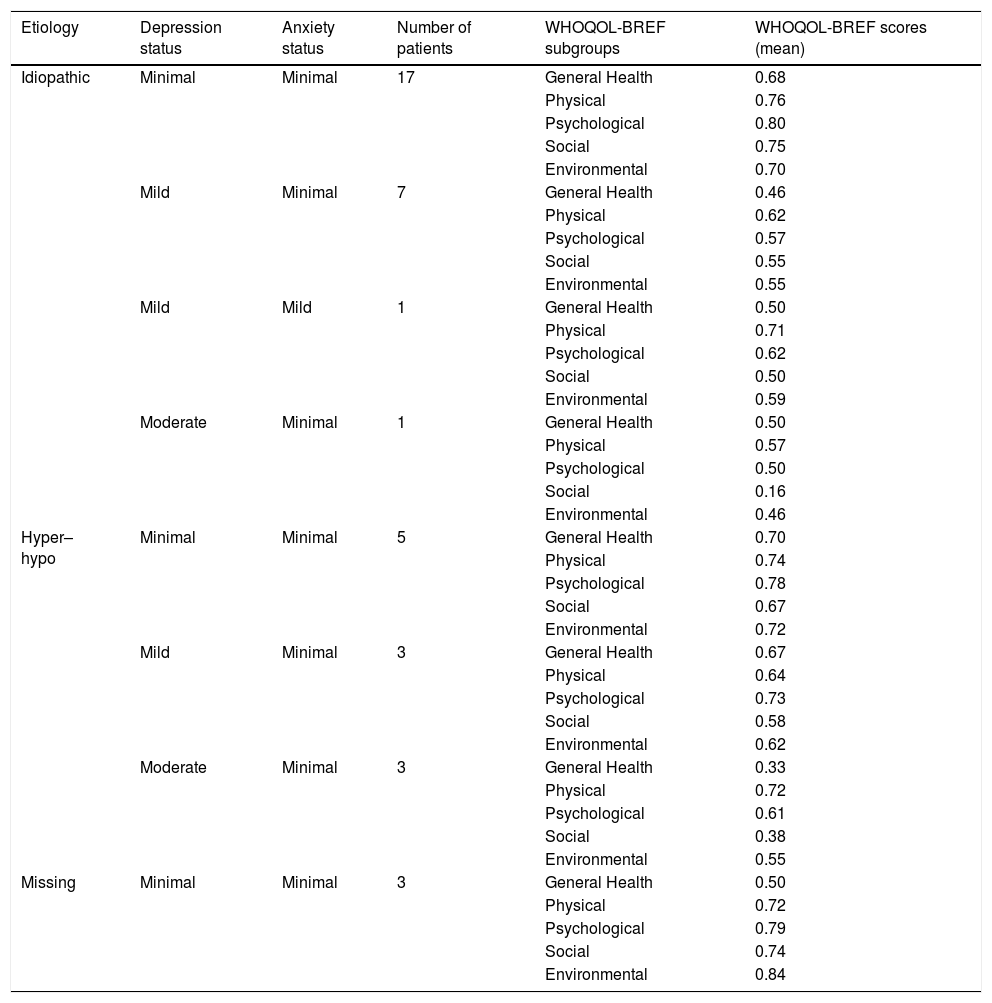

Detailed psychological conditions of the patients are shown in Table 2. In this cohort, 62.5% (n=25) of patients had minimal depression, 27.5% (n=11) of patients had mild depression and 10% (n=4) of patients had moderate depression. In this cohort, 97.5% (n=39) of patients had minimal anxiety and 2.5% (n=1) of patients had mild anxiety.

Detailed examination of patient groups according to depression, anxiety and quality of life scores.

| Etiology | Depression status | Anxiety status | Number of patients | WHOQOL-BREF subgroups | WHOQOL-BREF scores (mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idiopathic | Minimal | Minimal | 17 | General Health | 0.68 |

| Physical | 0.76 | ||||

| Psychological | 0.80 | ||||

| Social | 0.75 | ||||

| Environmental | 0.70 | ||||

| Mild | Minimal | 7 | General Health | 0.46 | |

| Physical | 0.62 | ||||

| Psychological | 0.57 | ||||

| Social | 0.55 | ||||

| Environmental | 0.55 | ||||

| Mild | Mild | 1 | General Health | 0.50 | |

| Physical | 0.71 | ||||

| Psychological | 0.62 | ||||

| Social | 0.50 | ||||

| Environmental | 0.59 | ||||

| Moderate | Minimal | 1 | General Health | 0.50 | |

| Physical | 0.57 | ||||

| Psychological | 0.50 | ||||

| Social | 0.16 | ||||

| Environmental | 0.46 | ||||

| Hyper–hypo | Minimal | Minimal | 5 | General Health | 0.70 |

| Physical | 0.74 | ||||

| Psychological | 0.78 | ||||

| Social | 0.67 | ||||

| Environmental | 0.72 | ||||

| Mild | Minimal | 3 | General Health | 0.67 | |

| Physical | 0.64 | ||||

| Psychological | 0.73 | ||||

| Social | 0.58 | ||||

| Environmental | 0.62 | ||||

| Moderate | Minimal | 3 | General Health | 0.33 | |

| Physical | 0.72 | ||||

| Psychological | 0.61 | ||||

| Social | 0.38 | ||||

| Environmental | 0.55 | ||||

| Missing | Minimal | Minimal | 3 | General Health | 0.50 |

| Physical | 0.72 | ||||

| Psychological | 0.79 | ||||

| Social | 0.74 | ||||

| Environmental | 0.84 |

WHOQOL-BREF-TR scores of the patients were 58.75%±19.24 (0.13–1) for general health status, 70.98%±13.41 (0.43–0.96) for physical health status, 72.92%±14.97 (0.46–1) for psychological status, 65%±22.97 (0.08–1) for social relations and 66.25%±17.07 (0.28–1) for environmental status.

When the severity of depression increased, all of the quality of life data were found to be decreased. It was determined that the general health status, which is one of the parameters of quality of life, has a significant inverse correlation with depression or anxiety of the patients (p=0.000, p=0.005) (Fig. 1).

There was no relation between depression versus duration of infertility (p=0.895), cigarette smoking (p=0.950), education status (p=0.618), having a chronic illness (p=0.565), or previous unsuccessful infertility treatment (p=0.942). There was also no relationship between anxiety and same parameters, either (p=0.061, p=0.826, p=0.423, p=0.583, p=342, respectively).

We also could not find any relation between etiologic classification of patients versus depression or anxiety status (p=0.682, p=0.916).

DiscussionAzoospermia is called as the absence of spermatozoa in the semen.5 It is classified as OA or NOA. Spermatogenesis in the testis is usually abnormal in NOA patients.28 In NOA, there is a diagnostic process and treatment challenges that negatively affect the life of couples. If sperm cannot be obtained by m-TESE procedure in NOA, these patients have no other alternative to continue their reproduction. This difficult situation can create a pressure on NOA patients.

When the period of infertility is prolonged, spouses’ blame of each other and deterioration in marital adjustment may become apparent. As a result, marriage may weaken in time and may even sometimes result in divorce. In other words, NOA is a condition that can affect patients’ family, friends and other environmental relations, sexual and social life and quality of life. Although there have been many studies on the etiology, treatment and follow-up of azoospermic individuals, the psychiatric aspects of azoospermia and the social, psychological consequences of infertility related to the lives of individuals have not been adequately investigated.

Current studies have shown that depression and anxiety are more common in infertile men.9–11

Drosdzol et al. reported that comparable frequency of negative results for depression and anxiety in infertile men.9 Statistically, depression and anxiety were more frequent in infertile men than in fertile men (respectively, p=0.048 and p=0.02). In their study, it was shown that male infertility and the duration of infertility up to 3–6 years was a risk factor for depression and anxiety. In our study, the mean duration of infertility was 29.1 months. In our study, we found minimal depressive symptoms in 62.5% and minimal anxiety in 97.5% of our patients. Yang et al. reviewed a broad-based questionnaire survey of psychiatric symptoms in infertile Chinese men.13 The frequency of depression and anxiety in the study was 20.8% and 7.8%, respectively. They found a significant relationship between the duration of infertility of more than 2 years and the high risk of anxiety symptoms (p<0.02). In our study, we found minimal depression and anxiety in 25 patients, and most of them were in the idiopathic infertility group (n=17). Ahmadi et al. examined only the depression and conducted a study to assess the frequency with Beck depression questionnaire in infertile men.11 According to them, if the total score was ≥17, they defined the condition as depression. In their study, depression was detected in 42.9% of infertile men. It was also shown that there was a statistically significant relationship between depression and education (p<0.001), smoking (p<0.008) and duration of infertility (p<0.03). We determined that the BDI score above 10 points in 11 patients and above 19 points in 4 patients. If we used the same cut off in our study too, 7 (17%) patients were detected to have depression in NOA. Comparing our study with other studies, the depression rate seemed to be lower in NOA than other infertility causes. However, we could not find any relation between depression and duration of infertility, cigarette smoking, education status, or having a chronic illness in patients with NOA. We also could not find any relation between these parameters and anxiety, either. Babore et al. recommended that infertile men should be screened for depressive symptoms before starting treatment with assisted reproductive techniques.3 Because these patients may experience a problem that can be ignored by doctors during infertility treatments. In our study, we found minimal, mild and moderate depressive symptoms in all patients. Of the 40 patients, 11 had mild and 4 had moderate depression. Therefore, patients who apply for NOA treatment should be referred to psychiatrists, if necessary. They also reported that half of the infertile men completed a secondary school, but in our study, about half of our patients has graduated from university (45%).

As seen, NOA is not a simple urological disease, it is particularly affecting the men in terms of biological, psychological and social aspects. This condition may decrease health and quality of life. Psychological symptoms of patients may not take the attention of doctors. It is important to examine the patients in both bio and psychosocially, and provide psychiatric support when if necessary. In previous studies, the quality of life of infertile men has been evaluated by authors but NOA have not been mentioned as a subgroup.6 They could not find significant results in terms of quality of life among infertile and fertile men (p>0.05). In our study, in the WHOQOL-BREF-TR, which consists 5 sub-groups, the lowest score was determined in the general health section (58.75%), an interestingly, the highest score was observed in psychological health section (72.92%). This can be explained by the fact that most patients consider this condition as both: a general health problem and a psychological problem.

ConclusionOne of the basic instincts of man is the capability of breeding and continuing the generation. Dissatisfaction with this instinct can be result in stress. As a result, men who are in the pursuit of azoospermia therapies may have a problem that can be ignored by doctors at this time. In order to evaluate the quality of life and psychiatric conditions patients with azoospermia, various questionnaires may be applied before infertility treatment. Thus, patients who need psychiatric support can be identified.

Limitations of the studyThough our study has a prospective construction, it has some limitations. First of all our patient populations were not big enough. Secondly, the effects of male infertility on psychiatric symptoms could be understood more clearly by comparing with the other male infertility reasons except NOA. In spite of these limitations, there is no study in the literature that evaluates depression, anxiety and quality of life of NOA patients. In this study, we have shown that it can be a resource for urologists and psychiatrists for future research.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Turgay Ebiloğlu coordinated and helped to draft the manuscript, Selçuk Sarıkaya find patients group, Adem Emrah Coğuplugil and Selahattin Bedir get results, performed statistical analyze and Ömer Faruk Karataş collected samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.