The development of sexual dysfunction (SD) in dialysis patients is multifactorial. We aimed to evaluate whether adequate dialysis had an effect on the development of SD in male and female patients undergoing dialysis due to end stage renal disease. Anxiety, depression, health-related quality of life and the other risk factors related to dialysis were also evaluated in terms of SD.

MethodsSeventy men and 57 women undergoing haemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) and 65 healthy male volunteers and 48 healthy female volunteers, age-matched, were included in the study. The International Index of Erectile Function, Female Sexual Function Index, Beck Depression Inventory, Beck Anxiety Inventory and The Short Form-36 Health Survey were applied to all participants. The cut off value of Kt/V was determined as 1.3 for HD and 1.7 for PD to assess dialysis adequacy. Per gender, all the participants were divided into three groups as control, adequate dialysis and non-adequate dialysis.

ResultsDialysis adequacy [OR: 3.225, 95%CI (1.213–8.620), p=.019] was found as a more decisive factor for male SD, while dialysis adequacy [OR: 3.015, 95%CI (.991–7.250), p=.041] and depression [OR: 4.280, 95%CI (1.705–10.747), p=.002] were more significant for female SD. In addition, a strong relationship was found between male SD and physical functioning (r: .524, p=.032), social functioning (r: .565, p=.042), general health (r: .693, p=.037) perception, while female SD was found to be strongly associated with anxiety (r: −.697, p=.002) and depression (r: −.738, p=.001).

DiscussionDialysis adequacy was found to be the most important factor in reducing SD. Non-adequate dialysis resulted in worse sexual function, higher levels of depression and anxiety. Its negative effect on health-related quality of life was only seen in men.

El desarrollo de la disfunción sexual (DS) en pacientes en diálisis es multifactorial. El objetivo fue evaluar si la diálisis adecuada tuvo un efecto sobre el desarrollo de la DS en los pacientes masculinos y femeninos sometidos a diálisis debido a enfermedad renal en etapa terminal. La ansiedad, la depresión, la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud y los otros factores de riesgo relacionados con la diálisis también se evaluaron en términos de DS.

MétodosSetenta varones y 57 mujeres sometidos a hemodiálisis (HD) o diálisis peritoneal (PD) y 65 voluntarios varones sanos y 48 voluntarias sanas se incluyeron para estudiar. Se aplicaron a todos los participantes el índice internacional de la función eréctil, el índice de la función sexual femenina, el inventario de depresión de Beck, el inventario de ansiedad de Beck y el formulario breve-36 encuesta de salud. El valor de corte de Kt/V se determinó como 1,3 para HD y 1,7 para PD para evaluar la adecuación de la diálisis. Para cada género, todos los participantes se dividieron en 3 grupos como control, diálisis adecuada y diálisis no adecuada.

ResultadosAdecuación de la diálisis (OR: 3,225; IC 95%: 1,213-8,620; p=0,019) se encontró un factor más decisivo para la DS masculina, mientras que la adecuación de la diálisis (OR: 3,015; IC 95%: 0,991-7,250; p=0,041) y depresión (OR: 4,280; IC 95%: 1,705-10,747; p=0,002) fueron más significativas para las mujeres con DS. Además, se encontró una fuerte relación entre la DS de los varones y el funcionamiento físico (r: 0,524; p=0,032), el funcionamiento social (r: 0,565; p=0,042), la percepción general de salud (r: 0,693; p=0,037), mientras que se descubrió que la DS femenina estaba fuertemente asociada con la ansiedad (r: −0,697; p=0,002) y la depresión (r: −0,738; p=0,001).

DiscusiónLa adecuación de la diálisis se encontró como el factor más importante para reducir la DS. La diálisis no adecuada resultó en una función sexual peor, niveles más altos de depresión y de ansiedad. Su efecto negativo en la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud solo se observó en los hombres.

The development of sexual dysfunction (SD) is multifactorial in dialysis patients. The accumulation of toxic materials due to chronic renal failure (CRF) may trigger renal failure-associated atherosclerosis, anemia, dyslipidemia. The smooth muscle and structural components of the erectile tissue would be negatively affected by this hypoxia related mechanism.1 The hormonal changes, the side effects of medications used in CRF and the psychological effects based on CRF such as depression, anxiety may also disturb patients’ sexual health.2 The psychosomatic effects related to CRF may have bad effects on quality of life. This may also trigger SD. These factors cause a vicious cycle that affect each other.

The adequate dialysis is expected to protect the residual renal function (RRF) and decrease the metabolic and hormonal dysfunction in patients with end stage renal disease (ESRD). The mostly used method to assess dialysis adequacy is Kt/V. It shows an average urea clearance. The average value of Kt/V should be at least 1.2 over three consecutive months. This value may be improved by increasing either time on dialysis or blood flow through the dialyzer.3

Although there are many studies about SD in men and women with ESRD, common deficiencies in literature are not evaluating the level of depression, anxiety and the quality of life based on SD.4–6 We aimed to predict independent risk factors that may affect the development of SD in both genders, undergoing dialysis. We also aimed to investigate whether adequate dialysis will have a positive effect on SD. According to our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the factors affecting SD in detail.

Materials and methodsPatient selectionOur study was designed as a prospective, cross-sectional study after obtaining the approval of the local ethics committee (protocol number: 77192459-050.99-E.2813, 3/18) and written informed consent from all participants.

The married men and women with ESRD undergoing on hemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD) under stable medical condition at the same dialysis center were assessed between March 2019 and May 2019. The presence of SD, depression, anxiety and the quality of life were evaluated through the questionnaire forms. Among them, 70 men and 57 women who were eligible and willing to participate in the study were included. In addition, age-matched 65 healthy male volunteers and 48 healthy female volunteers were included as control group. The control group consisted of healthy participants presenting for routine check up to urology or nephrology outpatient clinics with normal renal function.

The HD group was chosen from patients receiving HD three times a week for 4h at the dialysis center for at least 6 months. The PD group was chosen from patients undergoing automated PD for at least 6 months. The inclusion criterias were following: between the ages of 18 and 70 years, male and female gender, undergoing dialysis for at least 6 months and regularly followed up at the same dialysis center, sexually active, married, no psychiatric disease including depression or anxiety in the previous 6 months, having enough mental capacity and being literate to understand and answer the questionnaire forms.

The exclusion criterias were following: Patients who refused to participate the study, without a sexual partner, those with cognitive or auditory impairment, previous pelvic operations, being undergone surgical menopause, those with major psychiatric disorders, having used hormone replacement therapy within the last 5 years and those with severe diseases (such as acute congestive heart failure, stroke, peritonitis and acute complications of uremia) within the last month.

Male and female participants were evaluated separately. In both gender, all participants were divided into three groups as control, adequate dialysis and non-adequate dialysis.

Demographic and clinical dataAge, body mass index, etiology of renal failure, type of dialysis, dialysis duration, educational level, comorbidities, hematologic and biochemical parameters were recorded.

The assessment of sexual function, depression, anxiety and health related quality of lifeAll sexual assessment surveys were intended for participants who were sexually active in the previous four weeks. For avoiding any unnecessary embarrassments related to sexual assessment, a male doctor was chosen for male participants, while a female nurse for female participants. Face-to-face interviews with all participants were obtained. They were explained how to fill in the questionnaires. The responses of the participants were not interfered.

International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)It is a self-administered fifteen-item validated questionnaire and used to assess male SD.7 The domains of erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, sexual satisfaction and overall satisfaction are scored separetaly.

Patients with a score of ≤25 for the erection domain are considered to have ED. The severity levels of ED are classified as: none (26–30), mild (22–25), mild/moderate (17–21), moderate (11–16), and severe (0–10). For the other domains, higher scores indicate better function.

Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)It is a nineteen-item validated questionnaire and used for the assessment of female SD.8 The domains of desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain during sexual intercourse are assessed separately. Each domain is scored between 0 and 6. The full score ranges from 2 to 36. Higher scores indicate better function for each domain. The score below 22.7 is defined as female SD.2

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)It is a twenty one-item validated questionnaire and used to measure the presence and severity of depressive symptoms.9 Each item is scored from 0 to 3 based on severity of symptoms. The total score ranges from 0 to 63. The severity of depression is classified as: mimimal (0–9), mild (10–16), moderate (17–29), and severe (30–63).

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)It is a twenty one-item validated questionnaire and used to measure the presence and severity of anxiety symptoms.10 Each item is scored on a scale value of 0 to 3 and total score ranges from 0 to 63. The severity of anxiety is classified as: mimimal (0–7), mild (8–15), moderate (16–25), and severe (26–63).

The Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF36)The SF-36 is a thirty six-item validated assessment about the functional status and sense of well-being of patients with chronic diseases. It consists of eight scales.11 Physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health disease, role limitations due to emotional problems, energy/fatigue, emotional well being, social functioning, pain and general health perception are evaluated and scored separately. Each scales are worth for 100 points. The higher scores represent a better quality of life.

The assessment of adequate dialysisThe Kt/V value is commonly used to assess dialysis adequacy.12 The formula used to calculate is: Kt/V=−Ln (R−0.008×t)+(4–3.5×R)×UF/W. The abbreviations in this formula are as follows: K is clearance of urea, t is the dialysis session length in hours, V is distribution of urea, R is the ratio between post-dialysis blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and pre-dialysis BUN, UF is the ultrafiltration volume in liters and W is the patient's post-dialysis weight in kilograms.13

The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative guidelines and the Renal Association Clinical Practice guidelines state that if average Kt/V value for HD is over 1.3 for three consecutive months, it is defined as adequate dialysis. The cut off value of Kt/V for PD is 1.7 to assess dialysis adequacy.4,14 RRF was defined as at least 250ml daily urine volume in many studies.3,15 We made the distribution of patients according to these definitions. Because higher daily urine volume indicates better RRF, it is one of the valuable parameters in patients with ESRD.16

Statistical analysesKolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were used for the evaluation of normality. ANOVA test was used to detect the differences between three groups of normally distributed continuous variables and a Bonferroni-correction test was used as a multiple comparison test. Independent sample t test was performed in normal distribution between two dialysis groups, whereas Mann–Whitney-U test was performed in non-normal distribution. The Chi-square analysis was used for categorical variables, while Spearman's correlation test was used to investigate the association between questionnaires. A binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine the predictive factors for the development of SD. All analyses were made using the IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY USA) software package. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

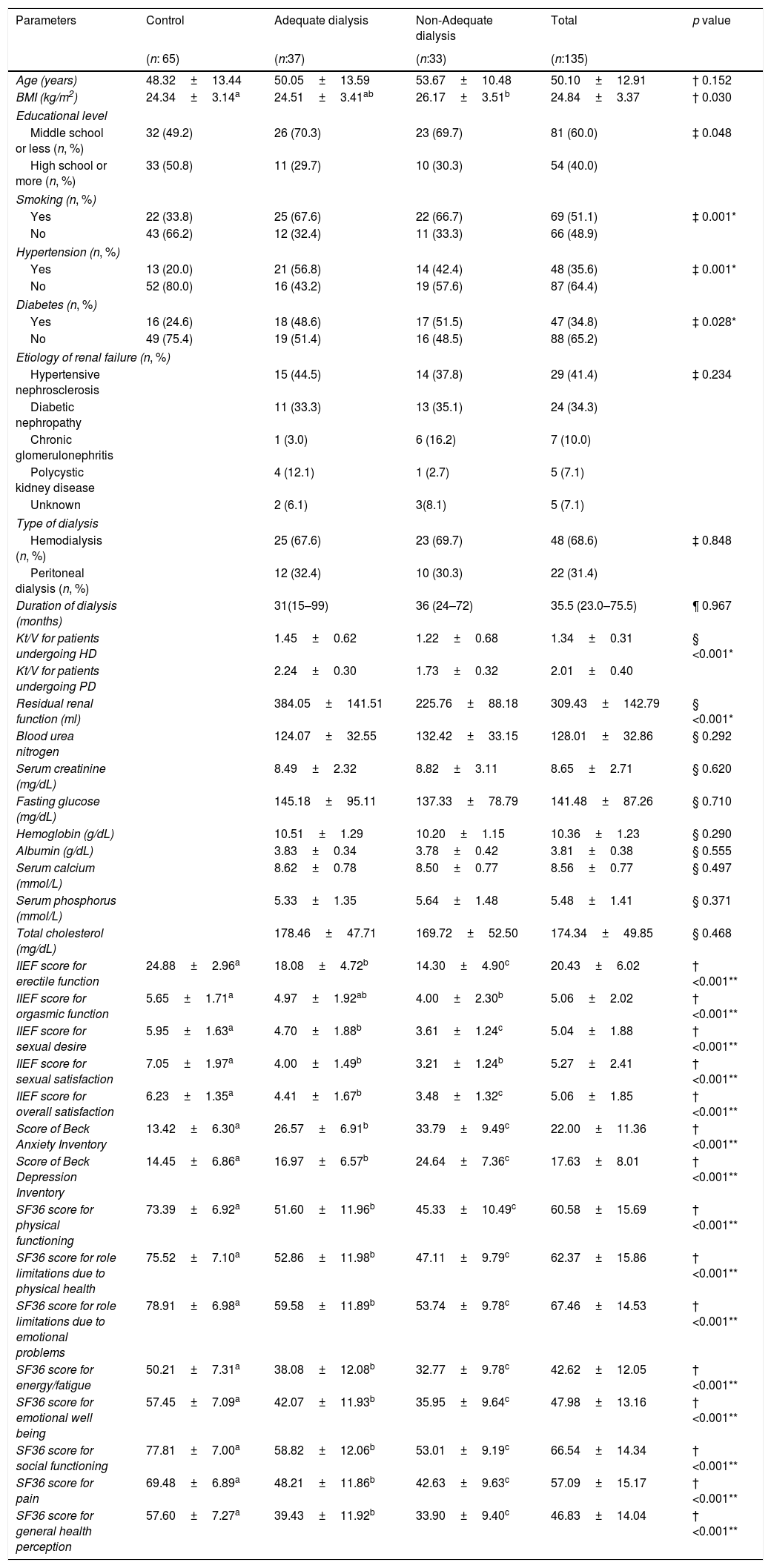

ResultsDemographic and clinical characteristics of the men and women are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the men included in the study.

| Parameters | Control | Adequate dialysis | Non-Adequate dialysis | Total | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n: 65) | (n:37) | (n:33) | (n:135) | ||

| Age (years) | 48.32±13.44 | 50.05±13.59 | 53.67±10.48 | 50.10±12.91 | † 0.152 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.34±3.14a | 24.51±3.41ab | 26.17±3.51b | 24.84±3.37 | † 0.030 |

| Educational level | |||||

| Middle school or less (n, %) | 32 (49.2) | 26 (70.3) | 23 (69.7) | 81 (60.0) | ‡ 0.048 |

| High school or more (n, %) | 33 (50.8) | 11 (29.7) | 10 (30.3) | 54 (40.0) | |

| Smoking (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 22 (33.8) | 25 (67.6) | 22 (66.7) | 69 (51.1) | ‡ 0.001* |

| No | 43 (66.2) | 12 (32.4) | 11 (33.3) | 66 (48.9) | |

| Hypertension (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 13 (20.0) | 21 (56.8) | 14 (42.4) | 48 (35.6) | ‡ 0.001* |

| No | 52 (80.0) | 16 (43.2) | 19 (57.6) | 87 (64.4) | |

| Diabetes (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 16 (24.6) | 18 (48.6) | 17 (51.5) | 47 (34.8) | ‡ 0.028* |

| No | 49 (75.4) | 19 (51.4) | 16 (48.5) | 88 (65.2) | |

| Etiology of renal failure (n, %) | |||||

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 15 (44.5) | 14 (37.8) | 29 (41.4) | ‡ 0.234 | |

| Diabetic nephropathy | 11 (33.3) | 13 (35.1) | 24 (34.3) | ||

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 1 (3.0) | 6 (16.2) | 7 (10.0) | ||

| Polycystic kidney disease | 4 (12.1) | 1 (2.7) | 5 (7.1) | ||

| Unknown | 2 (6.1) | 3(8.1) | 5 (7.1) | ||

| Type of dialysis | |||||

| Hemodialysis (n, %) | 25 (67.6) | 23 (69.7) | 48 (68.6) | ‡ 0.848 | |

| Peritoneal dialysis (n, %) | 12 (32.4) | 10 (30.3) | 22 (31.4) | ||

| Duration of dialysis (months) | 31(15–99) | 36 (24–72) | 35.5 (23.0–75.5) | ¶ 0.967 | |

| Kt/V for patients undergoing HD | 1.45±0.62 | 1.22±0.68 | 1.34±0.31 | § <0.001* | |

| Kt/V for patients undergoing PD | 2.24±0.30 | 1.73±0.32 | 2.01±0.40 | ||

| Residual renal function (ml) | 384.05±141.51 | 225.76±88.18 | 309.43±142.79 | § <0.001* | |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 124.07±32.55 | 132.42±33.15 | 128.01±32.86 | § 0.292 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 8.49±2.32 | 8.82±3.11 | 8.65±2.71 | § 0.620 | |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 145.18±95.11 | 137.33±78.79 | 141.48±87.26 | § 0.710 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.51±1.29 | 10.20±1.15 | 10.36±1.23 | § 0.290 | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.83±0.34 | 3.78±0.42 | 3.81±0.38 | § 0.555 | |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | 8.62±0.78 | 8.50±0.77 | 8.56±0.77 | § 0.497 | |

| Serum phosphorus (mmol/L) | 5.33±1.35 | 5.64±1.48 | 5.48±1.41 | § 0.371 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 178.46±47.71 | 169.72±52.50 | 174.34±49.85 | § 0.468 | |

| IIEF score for erectile function | 24.88±2.96a | 18.08±4.72b | 14.30±4.90c | 20.43±6.02 | † <0.001** |

| IIEF score for orgasmic function | 5.65±1.71a | 4.97±1.92ab | 4.00±2.30b | 5.06±2.02 | † <0.001** |

| IIEF score for sexual desire | 5.95±1.63a | 4.70±1.88b | 3.61±1.24c | 5.04±1.88 | † <0.001** |

| IIEF score for sexual satisfaction | 7.05±1.97a | 4.00±1.49b | 3.21±1.24b | 5.27±2.41 | † <0.001** |

| IIEF score for overall satisfaction | 6.23±1.35a | 4.41±1.67b | 3.48±1.32c | 5.06±1.85 | † <0.001** |

| Score of Beck Anxiety Inventory | 13.42±6.30a | 26.57±6.91b | 33.79±9.49c | 22.00±11.36 | † <0.001** |

| Score of Beck Depression Inventory | 14.45±6.86a | 16.97±6.57b | 24.64±7.36c | 17.63±8.01 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for physical functioning | 73.39±6.92a | 51.60±11.96b | 45.33±10.49c | 60.58±15.69 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for role limitations due to physical health | 75.52±7.10a | 52.86±11.98b | 47.11±9.79c | 62.37±15.86 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for role limitations due to emotional problems | 78.91±6.98a | 59.58±11.89b | 53.74±9.78c | 67.46±14.53 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for energy/fatigue | 50.21±7.31a | 38.08±12.08b | 32.77±9.78c | 42.62±12.05 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for emotional well being | 57.45±7.09a | 42.07±11.93b | 35.95±9.64c | 47.98±13.16 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for social functioning | 77.81±7.00a | 58.82±12.06b | 53.01±9.19c | 66.54±14.34 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for pain | 69.48±6.89a | 48.21±11.86b | 42.63±9.63c | 57.09±15.17 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for general health perception | 57.60±7.27a | 39.43±11.92b | 33.90±9.40c | 46.83±14.04 | † <0.001** |

BMI: Body mass index, IIEF: International Index of Erectile Function, SF36: The Short Form (36) Health Survey.

† Anova ‡ Chi-square § Independent sample t test ¶ Mann–Whitney U.

a, b, c: Statistically significant groups are shown in different letters. There is no statistical difference between the groups indicated by the same letter.

ab: The group that has no statistically significant difference from the other two groups.

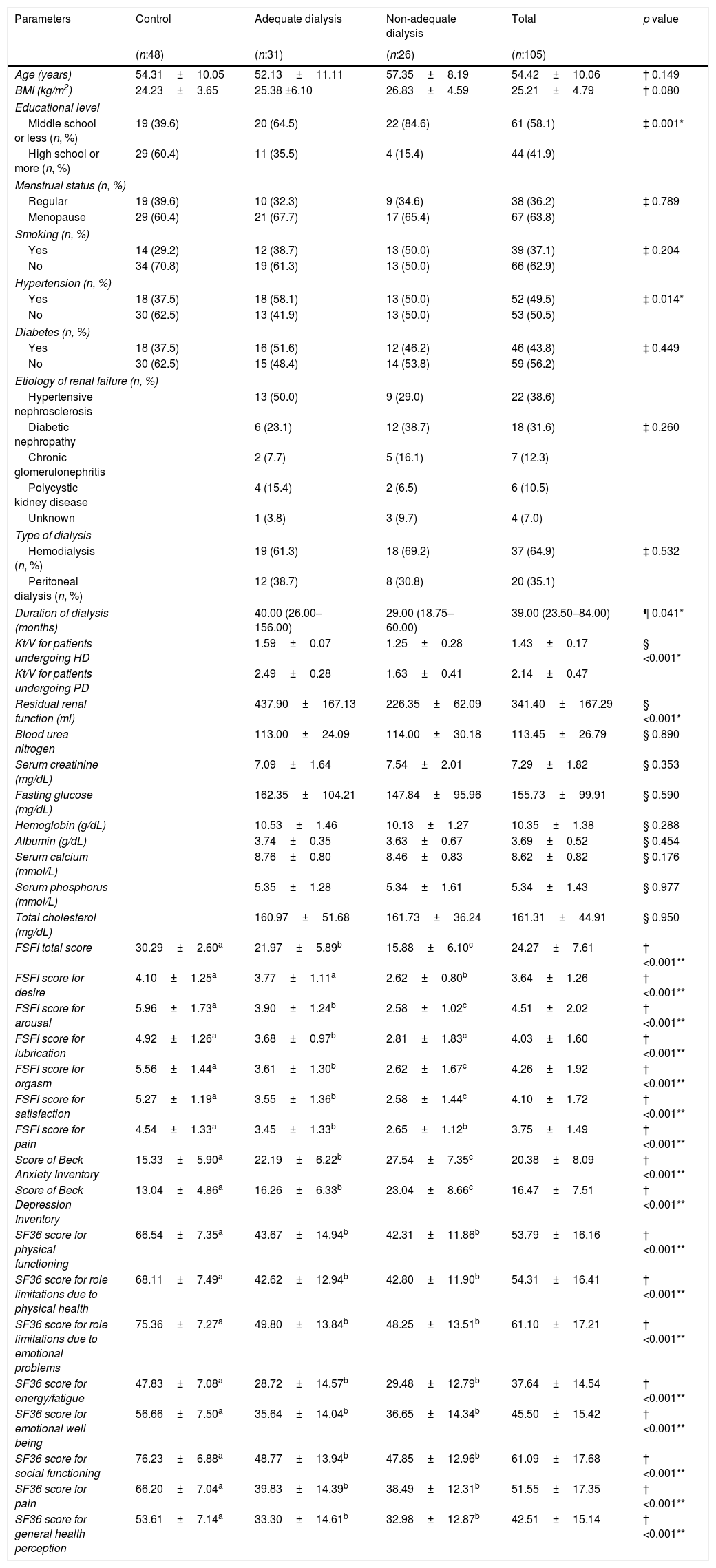

All domains of IIEF scores except ‘orgasmic function’ were significantly higher in control group than dialysis groups (Table 1). On the other hand, all domains of FSFI scores except ‘desire’ were significantly higher in control group (Table 2). In evaluation of both gender, scores of BAI and BDI were significantly lower in control group, while all domains of SF36 scores were significantly higher (Tables 1 and 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the women included in the study.

| Parameters | Control | Adequate dialysis | Non-adequate dialysis | Total | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n:48) | (n:31) | (n:26) | (n:105) | ||

| Age (years) | 54.31±10.05 | 52.13±11.11 | 57.35±8.19 | 54.42±10.06 | † 0.149 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.23±3.65 | 25.38 ±6.10 | 26.83±4.59 | 25.21±4.79 | † 0.080 |

| Educational level | |||||

| Middle school or less (n, %) | 19 (39.6) | 20 (64.5) | 22 (84.6) | 61 (58.1) | ‡ 0.001* |

| High school or more (n, %) | 29 (60.4) | 11 (35.5) | 4 (15.4) | 44 (41.9) | |

| Menstrual status (n, %) | |||||

| Regular | 19 (39.6) | 10 (32.3) | 9 (34.6) | 38 (36.2) | ‡ 0.789 |

| Menopause | 29 (60.4) | 21 (67.7) | 17 (65.4) | 67 (63.8) | |

| Smoking (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 14 (29.2) | 12 (38.7) | 13 (50.0) | 39 (37.1) | ‡ 0.204 |

| No | 34 (70.8) | 19 (61.3) | 13 (50.0) | 66 (62.9) | |

| Hypertension (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 18 (37.5) | 18 (58.1) | 13 (50.0) | 52 (49.5) | ‡ 0.014* |

| No | 30 (62.5) | 13 (41.9) | 13 (50.0) | 53 (50.5) | |

| Diabetes (n, %) | |||||

| Yes | 18 (37.5) | 16 (51.6) | 12 (46.2) | 46 (43.8) | ‡ 0.449 |

| No | 30 (62.5) | 15 (48.4) | 14 (53.8) | 59 (56.2) | |

| Etiology of renal failure (n, %) | |||||

| Hypertensive nephrosclerosis | 13 (50.0) | 9 (29.0) | 22 (38.6) | ||

| Diabetic nephropathy | 6 (23.1) | 12 (38.7) | 18 (31.6) | ‡ 0.260 | |

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | 2 (7.7) | 5 (16.1) | 7 (12.3) | ||

| Polycystic kidney disease | 4 (15.4) | 2 (6.5) | 6 (10.5) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (3.8) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (7.0) | ||

| Type of dialysis | |||||

| Hemodialysis (n, %) | 19 (61.3) | 18 (69.2) | 37 (64.9) | ‡ 0.532 | |

| Peritoneal dialysis (n, %) | 12 (38.7) | 8 (30.8) | 20 (35.1) | ||

| Duration of dialysis (months) | 40.00 (26.00–156.00) | 29.00 (18.75–60.00) | 39.00 (23.50–84.00) | ¶ 0.041* | |

| Kt/V for patients undergoing HD | 1.59±0.07 | 1.25±0.28 | 1.43±0.17 | § <0.001* | |

| Kt/V for patients undergoing PD | 2.49±0.28 | 1.63±0.41 | 2.14±0.47 | ||

| Residual renal function (ml) | 437.90±167.13 | 226.35±62.09 | 341.40±167.29 | § <0.001* | |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 113.00±24.09 | 114.00±30.18 | 113.45±26.79 | § 0.890 | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 7.09±1.64 | 7.54±2.01 | 7.29±1.82 | § 0.353 | |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 162.35±104.21 | 147.84±95.96 | 155.73±99.91 | § 0.590 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.53±1.46 | 10.13±1.27 | 10.35±1.38 | § 0.288 | |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.74±0.35 | 3.63±0.67 | 3.69±0.52 | § 0.454 | |

| Serum calcium (mmol/L) | 8.76±0.80 | 8.46±0.83 | 8.62±0.82 | § 0.176 | |

| Serum phosphorus (mmol/L) | 5.35±1.28 | 5.34±1.61 | 5.34±1.43 | § 0.977 | |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 160.97±51.68 | 161.73±36.24 | 161.31±44.91 | § 0.950 | |

| FSFI total score | 30.29±2.60a | 21.97±5.89b | 15.88±6.10c | 24.27±7.61 | † <0.001** |

| FSFI score for desire | 4.10±1.25a | 3.77±1.11a | 2.62±0.80b | 3.64±1.26 | † <0.001** |

| FSFI score for arousal | 5.96±1.73a | 3.90±1.24b | 2.58±1.02c | 4.51±2.02 | † <0.001** |

| FSFI score for lubrication | 4.92±1.26a | 3.68±0.97b | 2.81±1.83c | 4.03±1.60 | † <0.001** |

| FSFI score for orgasm | 5.56±1.44a | 3.61±1.30b | 2.62±1.67c | 4.26±1.92 | † <0.001** |

| FSFI score for satisfaction | 5.27±1.19a | 3.55±1.36b | 2.58±1.44c | 4.10±1.72 | † <0.001** |

| FSFI score for pain | 4.54±1.33a | 3.45±1.33b | 2.65±1.12b | 3.75±1.49 | † <0.001** |

| Score of Beck Anxiety Inventory | 15.33±5.90a | 22.19±6.22b | 27.54±7.35c | 20.38±8.09 | † <0.001** |

| Score of Beck Depression Inventory | 13.04±4.86a | 16.26±6.33b | 23.04±8.66c | 16.47±7.51 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for physical functioning | 66.54±7.35a | 43.67±14.94b | 42.31±11.86b | 53.79±16.16 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for role limitations due to physical health | 68.11±7.49a | 42.62±12.94b | 42.80±11.90b | 54.31±16.41 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for role limitations due to emotional problems | 75.36±7.27a | 49.80±13.84b | 48.25±13.51b | 61.10±17.21 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for energy/fatigue | 47.83±7.08a | 28.72±14.57b | 29.48±12.79b | 37.64±14.54 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for emotional well being | 56.66±7.50a | 35.64±14.04b | 36.65±14.34b | 45.50±15.42 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for social functioning | 76.23±6.88a | 48.77±13.94b | 47.85±12.96b | 61.09±17.68 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for pain | 66.20±7.04a | 39.83±14.39b | 38.49±12.31b | 51.55±17.35 | † <0.001** |

| SF36 score for general health perception | 53.61±7.14a | 33.30±14.61b | 32.98±12.87b | 42.51±15.14 | † <0.001** |

BMI: Body mass index, FSFI: Female Sexual Function Index, SF36: The Short Form (36) Health Survey.

† Anova ‡ Chi-square § Independent sample t test ¶ Mann–Whitney U.

a, b, c: Statistically significant groups are shown in different letters. There is no statistical difference between the groups indicated by the same letter.

ab: The group that has no statistically significant difference from the other two groups.

In the comparison of two dialysis groups, the domains of IIEF scores except ‘orgasmic function’ and ‘sexual satisfaction’ and the domains of FSFI scores except ‘pain’ were significantly higher in adequate dialysis group (Tables 1 and 2). The scores of BDI and BAI were significantly lower in adequate dialysis group in both genders (Tables 1 and 2).

In male patients, all domains of SF36 scores were significantly higher in adequate dialysis group than non-adequate dialysis group. Conversely, in female patients, the two dialysis groups did not differ in any of the domains of SF36 (Tables 1 and 2).

A strong relation was observed between RRF and Kt/V values in men (r: 0.763, p<0.001), However, the relation was weak for women (r: 0.369, p=0.005).

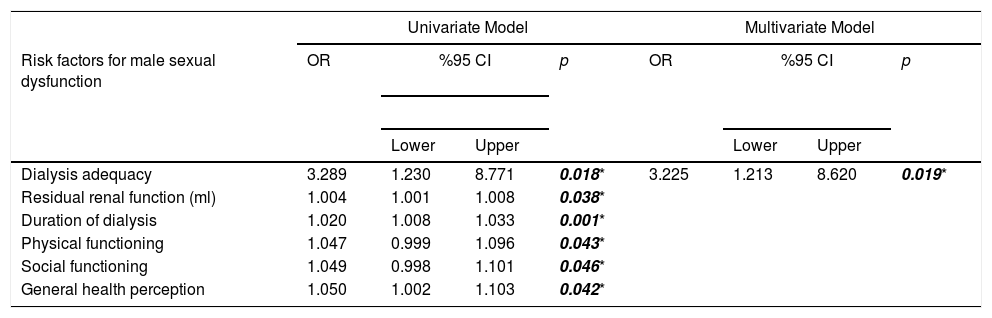

Dialysis adequacy, RRF, duration of dialysis, physical functioning, social functioning and general health perception were found as risk factors causing erectile dysfunction (ED) in men with ESRD in univariate analysis. But in multivariate analysis, dialysis adequacy (OR: 3.225, 95% CI 1.213–8.620, p=0.019) was more significant determinant (Table 3).

Risk factors causing male and female sexual dysfunction in patients with end-stage renal disease.

| Univariate Model | Multivariate Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors for male sexual dysfunction | OR | %95 CI | p | OR | %95 CI | p | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Dialysis adequacy | 3.289 | 1.230 | 8.771 | 0.018* | 3.225 | 1.213 | 8.620 | 0.019* |

| Residual renal function (ml) | 1.004 | 1.001 | 1.008 | 0.038* | ||||

| Duration of dialysis | 1.020 | 1.008 | 1.033 | 0.001* | ||||

| Physical functioning | 1.047 | 0.999 | 1.096 | 0.043* | ||||

| Social functioning | 1.049 | 0.998 | 1.101 | 0.046* | ||||

| General health perception | 1.050 | 1.002 | 1.103 | 0.042* | ||||

In univariate analysis, dialysis adequacy, anxiety and depression were found as risk factors causing female SD in women with ESRD. In multivariate analysis, dialysis adequacy (OR: 3.015, 95% CI 0.991–7.250, p=0.041) and depression (OR: 4.280, 95% CI 1.705–10.747, p=0.002) were more significant determinants (Table 3).

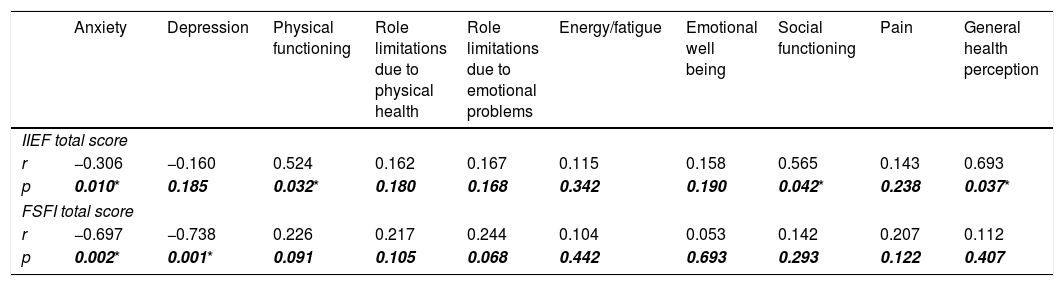

In correlation analysis, a strong relationship was found between ED and physical functioning, social functioning, general health perception (Table 4). The weak relationship between ED and anxiety did not gain importance according to univariate analysis. On the other hand, female SD was found to be strongly associated with anxiety and depression. However, it did not affect the quality of life (Table 4).

The correlations between sexual function assessment scores and other variates.

| Anxiety | Depression | Physical functioning | Role limitations due to physical health | Role limitations due to emotional problems | Energy/fatigue | Emotional well being | Social functioning | Pain | General health perception | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IIEF total score | ||||||||||

| r | −0.306 | −0.160 | 0.524 | 0.162 | 0.167 | 0.115 | 0.158 | 0.565 | 0.143 | 0.693 |

| p | 0.010* | 0.185 | 0.032* | 0.180 | 0.168 | 0.342 | 0.190 | 0.042* | 0.238 | 0.037* |

| FSFI total score | ||||||||||

| r | −0.697 | −0.738 | 0.226 | 0.217 | 0.244 | 0.104 | 0.053 | 0.142 | 0.207 | 0.112 |

| p | 0.002* | 0.001* | 0.091 | 0.105 | 0.068 | 0.442 | 0.693 | 0.293 | 0.122 | 0.407 |

SD is seen in 72–83% of patients with ESRD. Uremia is an important organic factor in the pathophysiology of SD.17 SD may develop in these patients due to peripheral neuropathy, anemia, dyslipidemia, hormonal changes, medical treatments given for CRF. Hypoxia-induced changes in vascular smooth muscles and erectile tissues may develop due to increased toxic substances.18,19 Psychological factors such as depression or anxiety caused by the presence of chronic disease and mental or physical fatigue caused by dialysis process may also increase the development of SD in both gender. Prevalence of SD is estimated to increase from 9% to 60–70% in both gender after starting dialysis.2 Our aim is to investigate whether the dialysis related factors effect SD and make additional contribution to improvement in sexual function in both gender by organizing dialysis related factors.

Spontaneous urine output, which is defined as RRF, decreases in dialysis patients. This situation reduces the excretion of metabolic products affecting the quality of life such as potassium, sodium, phosphate, uric acid. Consequently, effectiveness of dialysis may decrease. Preservation of RRF reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease by controlling blood pressure, preventing left ventricular hypertrophy, controlling anemia, and ensuring fluid-electrolyte balance. RRF is also an indicator of preserved glomerular filtration rate, tubular excretion rate, erythropoietin synthesis, calcium-phosphate-vitamin D hemostasis.20,21

High RRF levels provide body volume stabilization, control of arterial blood pressure, increase in erythropoietin secretion, elevated excretion of toxic substances. It is hypothesized that these mechanisms reduce risk of vascular calcification and all these conditions prevent development of ED. Conversely, decreased RRF is stated to be associated with endothelial dysfunction, which increases the predisposition to ED.22 In accordance with this hypothesis, we observed in both gender that RRF levels were higher in adequate dialysis group and sexual functions were better in higher RRF levels.

Stolic et al.3 stated that male patients undergoing HD with preserved RRF were found to have higher Kt/V values and less rates of ED. In our study, we found similar results in compatible with Stolic. Ye et al.22 found that ED was higher in men undergoing PD without preserved RRF. In contrast to our findings, although Kt/V value was significantly lower in their patients with ED, Kt/V value was not found to be a parameter affecting ED. They also found that RRF was associated with Kt/V value. The inconsistent result in the multivariate analysis can be attributed to the low rate of patients without ED (19.4% of all patients) in their study. One of their main limitations was also not to evaluate the relationship between depression and ED. In another study, a significant difference was not observed in the adequate and nonadequate HD groups in terms of FSFI scores. Compared to the healthy female volunteers, the rates of SD were higher in HD group.4 But they stated their limitations as not being a prospective study, not evaluating the depression status related to CRF, having a small patient population and not investigating other risk factors related to SD such as vascular abnormalities, medications, personal and social characteristics.

The incidence of SD was also found to be 5.23 times higher in women undergoing HD than in those undergoing PD according to Kettas et al.2 In addition, women with ESRD had more SD than healthy volunteers. We also found the SD rates higher in patients with ESRD, but the two types of dialysis did not differ in terms of SD development in both gender. According to the view of Kettas et al.2 dialysis treatment have a negative effect on patients’ quality of life. The effects are also depend on the dialysis type. The increased rate of peritonitis and catheter malfunction have been seen in patients undergoing PD. On the other hand, those undergoing HD are at greater risk of developing fistula, changes in the skin color, fatigue, headache, chest pain, decreased muscle tone, and weight loss. These changes in body image and also being dependent on a machine for lifetime may increase SD. Other studies supporting their opinion, specified that SD increases from 9% to 60–70% in both gender after starting dialysis.2,17,23 On these studies, it is believed that these negative effects may be related to self-concept, intimate relationship or family/social roles rather than negative physiologic effects associated with CRF and dialysis.24 Although Kettas et al.2 shared this opinion, they did not compare the pre- and post-dialysis sexual functions of patients. Moreover, dialysis adequacy and the effects of depression, anxiety and quality of life on SD were not evaluated to support their findings.

Savadi et al.25 administered the IIEF questionnaire to the male patients with CRF who were first-time candidates for routine HD. The evaluation was done before the first HD and at the end of the sixth month. According to their results, a six-month course of HD improved all domains of IIEF. But they did not evaluate dialysis adequacy. Unlike many other studies and ours, the mean patient age in their study was 40. They found that the most important factor affecting the improvement in sexual performance quality in HD patients was young age. But in their comment, they stated that young patient age and also inclusion of a small number of patients may cause this difference in results. As in this study, there are some common hypotheses in the other studies which explain that sexual function improves after HD.26–28 Firstly, cleaning the toxin-induced uremic blood may provide improvements in hormonal disorders. In addition, an increase in hematocrit may also help to improve the quality of erection. But according to the opposite idea, HD alone may not be enough to compensate vascular and nervous damages or emotional and social problems caused by CRF.29 However, additional predisposing factors such as endocrine, cardiovascular, psychological, and social disorders or the high prevalence of depression associated with CRF that may cause SD were not excluded in most studies.25,29,30 As a result, this limitation may cause differences in findings.

Although a significant improvement in quality of life was observed, the rate of ED was stated to decrease from 32.2–61.7% to 20–50% in both kidney transplants recipients and patients undergoing HD in the study of Yavuz et al.31 Despite the decreases in ED, these rates were expressed to be high. The main reasons for this high rate were shown as accompanying intensive pharmacologic treatments, major surgeries, psychological and physical stresses, anxiety, and changes in self image; even if patients of a closer age without atherosclerosis, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia or smoking habits were selected.

Azevedo et al.32 evaluated sexual function in patients aged 18–85 years, who underwent PD for at least 3 months via FSFI and IIEF. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the General Quality of Life Scale (EQ 5D) were applied to all patients to determine the level of depression and anxiety. SD was observed in 67.9% of female patients and in 44.8% of males. Increased calcium and low testosterone levels were associated with SD in men, while low albumin, creatinine, phosphorus levels and poor quality of life were found to be associated with SD in women. There were no statistically significant effects of adequate dialysis, depression and anxiety on SD in both gender. Our results were different from this study. All of our dialysis patients had SD at different severities in both genders. Hematologic and biochemical parameters had no differences between dialysis groups. Three domains of quality of life (physical functioning, social functioning and general health perception) were found as risk factors for ED in male patients. However, we did not find any domains of quality of life to be associated with SD in women. Dialysis adequacy was the main determinant for SD in both gender, while anxiety and depression were significant risk factors for SD in only female patients. Unlike the above-mentioned study, we also evaluated patients undergoing HD as well as PD patients.

In a study evaluating the effect of HD duration on ED, patients were divided into two groups in terms of HD duration (<10 years vs. >10 years). No significant difference was found between duration of dialysis and ED.5 According to our results, duration of dialysis is a determining risk factor in terms of ED in men with ESRD, while its importance on female SD was not shown. However, the median duration of dialysis (35.5 months) in our male patients was shorter than the above study.

Filocamo et al.6 evaluated SD and the level of depression in female patients with ESRD. Each patients were evaluated while undergoing HD for at least 6 months and re-evaluation was performed at 12 months after renal transplantation. There was a significant improvement in SD after transplantation. However, no significant correlation was found between female SD and severity of depression. In our study, although we did not have a transplantation group, there was no difference between type of dialysis in terms of SD development. But we observed that adequate dialysis provided better sexual function in both gender. The scores of BDI were significantly lower in adequate dialysis group than non-adequate dialysis group in our patients. Moreover, we found depression as a significant risk factor for female SD in women with ESRD.

According to our results, the dialysis adequacy has a direct protective effect on the sexual functions, so optimization of the dialysis programs is very important to provide better renal replacement treatment as well as sexual functions. If Kt/V values are low, increasing the dialysis time to at least 4h, increasing the blood flow rate to more than 300ml/min, increasing the dialysate flow rate to more than 800ml/min, increasing the frequency of dialysis, changing the dialysis membrane surface area or application of intradialytic exercise are recommended.13,33 An exponential decline in RRF is observed at the starting of dialysis.3 Horinek et al.34 declared that 58% of patients lost their RRF in the first eighteen months on HD. But there was a strong positive correlation between RRF and the dialysis adequacy. Therefore, improving the dialysis adequacy may preserve RRF. Both parameters are also stated to directly affect sexual functions.25,26,31

There was no significant difference between two dialysis groups in terms of age, BMI, educational level and comorbidities in our study. In addition, there was no difference in terms of menstrual status between female participants. The main statistically differences were belonged to the control group. In this way, we tried to form two homogeneous dialysis groups in terms of other characteristics. As a result, we tried to evaluate the effects of anxiety, depression, health related quality of life, factors associated with dialysis (dialysis adequacy, duration, type, Kt/V, RRF) on SD more accurately. We think that our study is more comprehensive because all domains of IIEF, FSFI, BAI, BDI and SF36 were evaluated in detail unlike the literature.

LimitationsOur first limitation is small number of patients in a single center. The participation rate in studies investigating sexual attitudes is generally low and the degree of conservatism in sexual attitudes is high in our society. Even so, we determined sample size based on statistical power analysis and it is larger than other similar studies mentioned above.

Secondly, as we could not evaluate sex hormone levels, we could not observe whether there was a decrease in these values due to ESRD and whether these values were significantly different in patients with dialysis adequacy. We also could not assess whether differences in hormone levels had an impact on SD, anxiety, depression, or health-related quality of life.

Thirdly, we could not compare sexual functions between pre-dialysis and post-dialysis. It is difficult to find a patient with ESRD who has not yet received dialysis because symptom onset is diverse, indication and the type of dialysis differ according to each patient's health condition.

ConclusionSD may develop in male and female patients undergoing HD or PD. Dialysis adequacy is the most important target in reducing SD in our study. Dialysis-related insufficiency worsens female sexual function, the levels of depression and anxiety but it does not negatively affect health-related quality of life in women. In male patients, the increased SD caused by dialysis-related insufficiency affects health-related quality of life more significantly. In the vicious circle, the decrease in health related well-being further reduces male sexual function.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Authors’ contributionSelvi I: the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Sarikaya S: the conception and design of the study, revising the article critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Atilgan KG: the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, revising the article critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Ayli MD: the conception and design of the study, revising the article critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Informed consentFormal written informed consent was also supplied from all participants.

Funding sourcesThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.