To determine the factors that cause erectile dysfunction and penile curvature after repair of penile fracture (PF).

MethodsData from 25 patients who underwent PF repair was retrospectively analyzed. PF was diagnosed by examining patients’ medical histories and performing physical examinations. All patients underwent immediate PF repair. All patients filled out the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) form and penile curvature was examined.

ResultsThe median age of patients at the time of surgery and the median follow-up duration were 46 years (22–60 years) and 95 months (12–156 months), respectively. Two of the patients had concomitant urethral injury. At the final follow up, erectile dysfunction (ED) was present in 13 patients (52%). Among these patients, 9 patients (36%) had mild ED and 4 patients (16%) had moderate ED. With a univariate analysis, age and penile curvature were significantly associated with ED (p=0.008 and p=0.039, respectively). With a multivariate analysis, age was independently associated with ED (p=0.048, odds ratio=1.104, 95% confidence interval 1.000–1.218). The IIEF-5 scores correlated with age (p=0.009, r=0.510). Seven patients (28%) had penile curvature and one patient underwent penile plication surgery.

ConclusionAfter PF repair, age is the only risk factor for ED and penile curvature rarely requires surgical treatment.

Determinar los factores que causan disfunción eréctil y curvatura de pene tras una reparación de fractura de pene (FP).

MétodosSe analizaron retrospectivamente los datos de 25 pacientes sometidos a reparación de FP. Se diagnosticó FP examinando las historias clínicas de los pacientes y realizando exploraciones físicas. Se sometió a todos los pacientes a reparación inmediata de FP. Todos los pacientes completaron el formulario IIEF-5 (International Index of Erectile Function), y se examinó la curvatura de pene.

ResultadosLa edad media de los pacientes en el momento de la cirugía y la duración media del seguimiento fueron de 46 años(22–60 años) y 95 meses (12–156 meses), respectivamente. Dos pacientes tuvieron lesión uretral concomitante. Al finalizar el seguimiento se presentó disfunción eréctil (DE) en 13 pacientes (52%). Entre estos pacientes, nueve (36%) tuvieron DE leve y cuatro (16%) DE moderada. Con un análisis univariante, la edad y la curvatura de pene estuvieron significativamente asociadas a DE (p = 0,008 y p = 0,039, respectivamente). Con un análisis multivariante, la edad estuvo independientemente asociada a DE (p = 0,048, odds ratio = 1,104, 95% de intervalo de confianza 1,000–1,218). Las puntuaciones IIEF-5 se correlacionaron con la edad (p = 0,009, r = 0,510). Siete pacientes (28%) tuvieron curvatura de pene y un paciente fue sometido a cirugía de plicatura de pene.

ConclusiónTras la reparación de FP, la edad es el único factor de riesgo de DE, y la curvatura de pene raramente requiere tratamiento quirúrgico.

Penile fracture (PF) is a rare urological emergency that is defined as disruption to the tunica albuginea and rupture of the corpus cavernosum. The incidence and etiology of PF vary in different regions of the world.1,2 PF typically occurs during sexual intercourse when an erect penis strikes the pubic bone or perineum. Other etiologies of PF are forceful manipulation of the penis (taqaandan), rolling over in bed while the penis is erect, and forceful bending of the penis during masturbation.

Although there is no consensus on the optimal treatment for PF, early surgical repair has increased in popularity due to functional results.3,4 However, there is no evidence-based algorithm for diagnosis and treatment. The most common long-term PF-related problems are erectile dysfunction (ED), penile curvature, and induration.3 However, due to the fact that most patients with PF are lost during follow up, it is difficult to determine the complication rates and the factors that influence them.

In this study, we present our surgical outcomes and aim to identify the risk factors for ED and penile curvature.

Materials and methodsThe present study was approved by the ethics committee at our university. Data from 28 patients who underwent PF repair between 2000 and 2018 was retrospectively analyzed. Patients were invited to the clinic for routine follow up. Patients who refused to provide informed consent or from whom data was missing were excluded from the study. A total of 25 patients were included in the study.

PF was diagnosed by examining patients’ medical histories and performing physical examinations. Patients diagnosed with PF underwent immediate surgery. All patients had received prophylactic antibiotics before surgery. Following a circumcising incision, the penis was degloved and the urethra and bilateral corpus cavernosum were inspected. The tunical defect was closed with interrupted 2-0 absorbable sutures and the urethra was repaired with 4-0 absorbable sutures. The urethral catheter was removed on postoperative day 1 if urethral repair was not performed.

All patients filled out the Turkish version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) form, which was validated.5 Patients were questioned whether they had penile deviation or not. Self-photography was planned for patients who complained of deviation erection during sexual intercourse. All patients underwent a clinical examination for penile induration. The time from injury to surgery was defined as the interval time.

Patient and public involvementThere was no involvement of patients or the public in the design of any aspect of the present study.

Statistical analysisData was analyzed using SPSS 24.0 (IBM Corp.) software. Univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were performed to determine factors causing ED and penile curvature. Nominal data was compared using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test in the univariate analysis. Median (range) was used for nonparametric data. Logistic regression analysis was used in the multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of <0.05.

ResultsThe median age of patients at the time of surgery was 46 years (range, 22–60 years) and the median follow up was carried out at 95 months (range, 12–156 months). Six patients (24%) had at least one comorbidity (e.g., coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus). The median interval time was 12h (range, 6–48h).

PF occurred during vaginal intercourse in 19 patients (76%), after rolling over in bed in 5 patients (20%), and due to forceful bending of the penis during masturbation in 1 patient (4%). Urethral injury was detected in two patients and one of these patients had urethrorrhagia. One patient underwent repeat surgery due to penile hematoma after sexual intercourse on postoperative day 24. Two years after the first repair, one patient underwent a second PF repair.

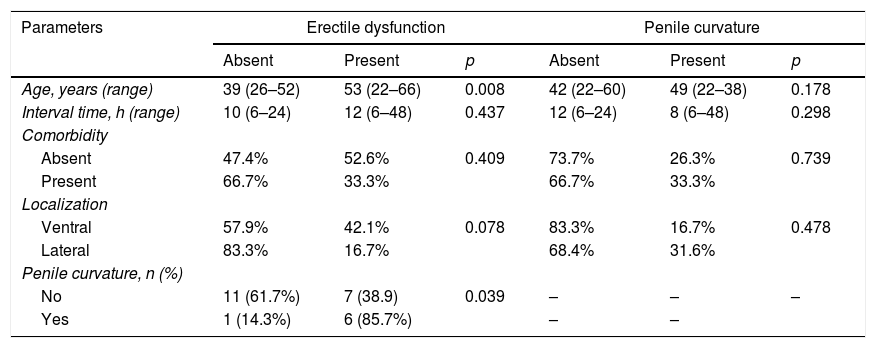

At the final follow up, ED had developed in 13 patients (52%). Of these patients, 9 patients (36%) had mild ED and 4 patients (16%) had moderate ED. With a univariate analysis, the interval time, presence of a comorbidity, and fracture localization were not significantly associated with ED (p=0.437, p=0.409, and p=0.078, respectively). Age and penile curvature were significantly associated with ED with a univariate analysis (p=0.008 and p=0.039, respectively; Table 1). With a multivariate analysis, age was an independent risk factor for ED (p=0.048, odds ratio=1.104, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.000–1.218). The IIEF-5 score correlated with age (p=0.009, r=0.510).

Univariate analysis to predict erectile dysfunction and penile curvature.

| Parameters | Erectile dysfunction | Penile curvature | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | p | Absent | Present | p | |

| Age, years (range) | 39 (26–52) | 53 (22–66) | 0.008 | 42 (22–60) | 49 (22–38) | 0.178 |

| Interval time, h (range) | 10 (6–24) | 12 (6–48) | 0.437 | 12 (6–24) | 8 (6–48) | 0.298 |

| Comorbidity | ||||||

| Absent | 47.4% | 52.6% | 0.409 | 73.7% | 26.3% | 0.739 |

| Present | 66.7% | 33.3% | 66.7% | 33.3% | ||

| Localization | ||||||

| Ventral | 57.9% | 42.1% | 0.078 | 83.3% | 16.7% | 0.478 |

| Lateral | 83.3% | 16.7% | 68.4% | 31.6% | ||

| Penile curvature, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 11 (61.7%) | 7 (38.9) | 0.039 | – | – | – |

| Yes | 1 (14.3%) | 6 (85.7%) | – | – | ||

Seven patients (28%) stated penile deviation, but only one of these patients underwent penile plication surgery. The patient who underwent plication surgery was the patient who had undergone PF repair twice. With a univariate analysis, age, interval time, presence of a comorbidity, and fracture localization were not statistically associated with penile curvature (p=0.178, p=0.298, p=0.739, and p=0.487, respectively; Table 1). Penile induration was detected in 3 patients (12%) and none of these patients had complaint.

DiscussionA physical examination and medical history are generally adequate for the diagnosis of PF.6 Reports of a characteristic cracking sound in the medical history, detumescence, and pain guide the clinician. The most common findings are penile hematoma, swelling, and penile deviation. Urethrorrhagia is typically associated with urethral injuries.7,8 In equivocal cases, ultrasonography (US) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to detect tear size and localization. Although US has poor sensitivity, the sensitivity of 1.5-T MRI is 100%; thus, it is a diagnostic tool with good accuracy.9–12 Routine urethrography is not recommended for all patients, but urethrography is an important diagnostic tool for patients with urethrorrhagia.7,13 We did not perform routinely urethrography.

In our study, we detected two urethral injuries: one in a patient with urethrorrhagia, in whom palpable urethral and tunical tears were detected upon physical examination; and the other in a patient who underwent penile degloving and hematoma evacuation. Radiologic imaging is not essential for all patients, except in equivocal cases. Firstly, the urethra must be inspected. Secondly, urethral continuity must be controlled with finger palpation upon the urethral catheter regardless of urethrorrhagia.

ED is probably the most feared complication after PF. For this reason, many studies evaluated erectile function after PF repair.4,14–18 The incidence of ED after PF repair was reported in a wide range. Hatzichristodoulou et al. reported that 53.8% of patients presented with impaired erectile function after PF repair with a median follow up of 45.6 months.16 Zargooshi reported a satisfactory erectile function rate of 95.2% in a study carried out on 170 patients.19 Reis et al.,15 also reported that 95.2% of patients had a sufficient erectile function after PF repair. Barros et al. reported that, out of a total of 58 patients, 13.8% of patients had ED after 6 months and only one patient had persistent ED after 18 months.20 They stated that psychological sequelae associated with fear of recurrence and psychogenic ED were common after PF repair. The possible reasons for different reporting of ED rate include geographic area, study sample size, age, and different follow-up periods. In a recent study, Ortac et al. found that ED was significantly correlated with tear size and age at a median follow up of 28 months.6 In our study, the prevalence of ED was 52%. Age was the only independent risk factor for ED, and IIEF-5 score correlated with age. The prevalence of ED increases with age due to vascular alterations, pressure changes, and morphological adaptations.21,22 The interval time and presence of a comorbidity were not statistically associated with ED in this study. Presence of a comorbidity may be associated with ED due to vascular or neuronal effects; however, only 6 patients presented with a comorbidity in our study, which might have affected our results due to the low number of patients.

Another important sequela of PF repair is penile curvature. Penile curvature after PF repair occurs in 1.1–30.8% of patients.16,23 In our study, penile curvature occurred in 25% of patients after PF repair and none of the factors (age, the interval time, presence of a comorbidity and fracture localization) were associated with penile curvature. Only one patient who underwent PF repair twice underwent penile curvature correction; the other patients had no complaints of pain or difficulty during sexual intercourse.

Another feared complication of PF is necrosis of the foreskin after circumcision by penile degloving.24 In our study, none of the patients experienced necrosis or wound infection. Only one patient had an early complication (i.e., penile hematoma); this patient underwent surgery. At follow up, only 3 patients (12%) had penile induration on physical examination and none of these patients had any complaint from induration.

The main limitations of our study were the small sample size and the retrospective design. Lack of psychological assessment may be considered another limitation. Our data did not include preoperative sexual assessments. In the follow-up period, patients with ED were not assessed by penile color duplex Doppler US to determine vascular abnormalities. Besides these limitations, considering the long follow-up period of our study compared with existing studies in the literature, we believe that our results provide a significant contribution to the literature.

ConclusionEarly surgical repair after PF has a low complication rate and satisfactory results. ED is associated with patient age after PF repair. Penile curvature is observed in almost a quarter of patients and rarely requires surgery.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThe authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestNone declared.