Radical orchiectomy in testicular cancer patients can have a negative impact on body image and self-esteem. Reconstructive surgery with testicular prosthesis might mitigate this burden. We conducted a questionnaire-based study aiming to evaluate our patients’ satisfaction with testicular prosthesis. Overall satisfaction was rated as excellent or good in 97.7%. The main complaints were related to the prosthesis’ inappropriate texture (45.5%), size (18.1%) or position (15.9%). Among men interviewed, 59% considered that having a normal looking scrotum was either extremely important or important for their self-esteem. The majority (88.2%) stated they would make the same decision again, and nearly all patients would recommend it to other men with testicular cancer. We believe testicular implants should always be offered, leaving the final decision to the patient.

La orquiectomía radical en los pacientes de cáncer de testículo puede tener un impacto negativo en su imagen corporal y autoestima. La cirugía reconstructora con prótesis testiculares podría mitigar esta carga. Realizamos un estudio basado en el uso de un cuestionario con el objetivo de evaluar la satisfacción de nuestros pacientes con las prótesis testiculares. La satisfacción general fue calificada como excelente o buena en el 97,7% de los casos. Las principales quejas guardaron relación con la textura inadecuada de las prótesis (45,5%), el tamaño (18,1%) o su posición (15,9%). Entre los varones entrevistados, el 59% consideró que tener un escroto con aspecto normal era extremadamente importante, o importante para su autoestima. La mayoría (88,2%) afirmó que volverían a tomar la misma decisión de nuevo, y casi todos los pacientes lo recomendarían a otros varones con cáncer de testículo. Consideramos que siempre deberían ofrecerse los implantes testiculares, dejando que el paciente tome siempre la decisión final.

Testicular cancer (TC) is the most common solid cancer in men between 20 and 35 years of age.1 Due to the young age at diagnosis and 5-year cancer specific survival rates around 95%,1 the prevalence of TC survivors (TCS) is rising.2,3 Apart from treatments’ toxicities, it is important to be aware of long-term sequelae of TC. From interview studies conducted in TCS in different cultural settings, evidence exists that radical orchiectomy (RO) can interfere with normal psychosexual function,4–6 represent a feeling of loss of masculinity and lead to a deterioration in perceived body Image.2,7,8 Reconstruction with testicular prosthesis (TP) may mitigate this impact, with numerous questionnaire-based studies showing increases in several parameters of well-being, including self-satisfaction, self-esteem and physical attractiveness.9–12 There is however a relatively low TP utilization rate,13,14 as counselling regarding this issue is not standardized worldwide and more than one-third of patients are not offered an implant at the time of RO.4,6,11

We aimed to evaluate satisfaction in patients submitted to TP placement following RO. With this data we intended to provide better counselling to our testicular cancer patients.

Materials & methodsAll patients undergoing radical orchiectomy for testicular cancer in our urology department, between 2013 and 2018, were contacted by phone call. They were asked if they had received a TP, and in case of a positive answer they were invited to participate in a survey regarding the satisfaction with their implant. Informed consent was obtained prior to each interview. The questionnaire, conducted in Portuguese, was comprised of 12 questions focused on three main areas. Firstly, the motivations leading the patients towards accepting a TP and their feedback on the preoperative counselling provided by the doctor; secondly, their evaluation of the implant's characteristics and global satisfaction; and lastly questions regarding the patient's insight on the implant's importance and whether they would recommend it to men with the same disease. The answers were evaluated qualitatively. We deemed a patient satisfied with the implant when they rated their global satisfaction either as “very good” or “excellent”. Clinical data from patients’ files were collected, namely: age at the time of RO, relationship status at the time of RO, time between RO and TP placement, time since TP placement, type of TP implanted, postoperative complications. Descriptive analyses were used to report pertinent variables.

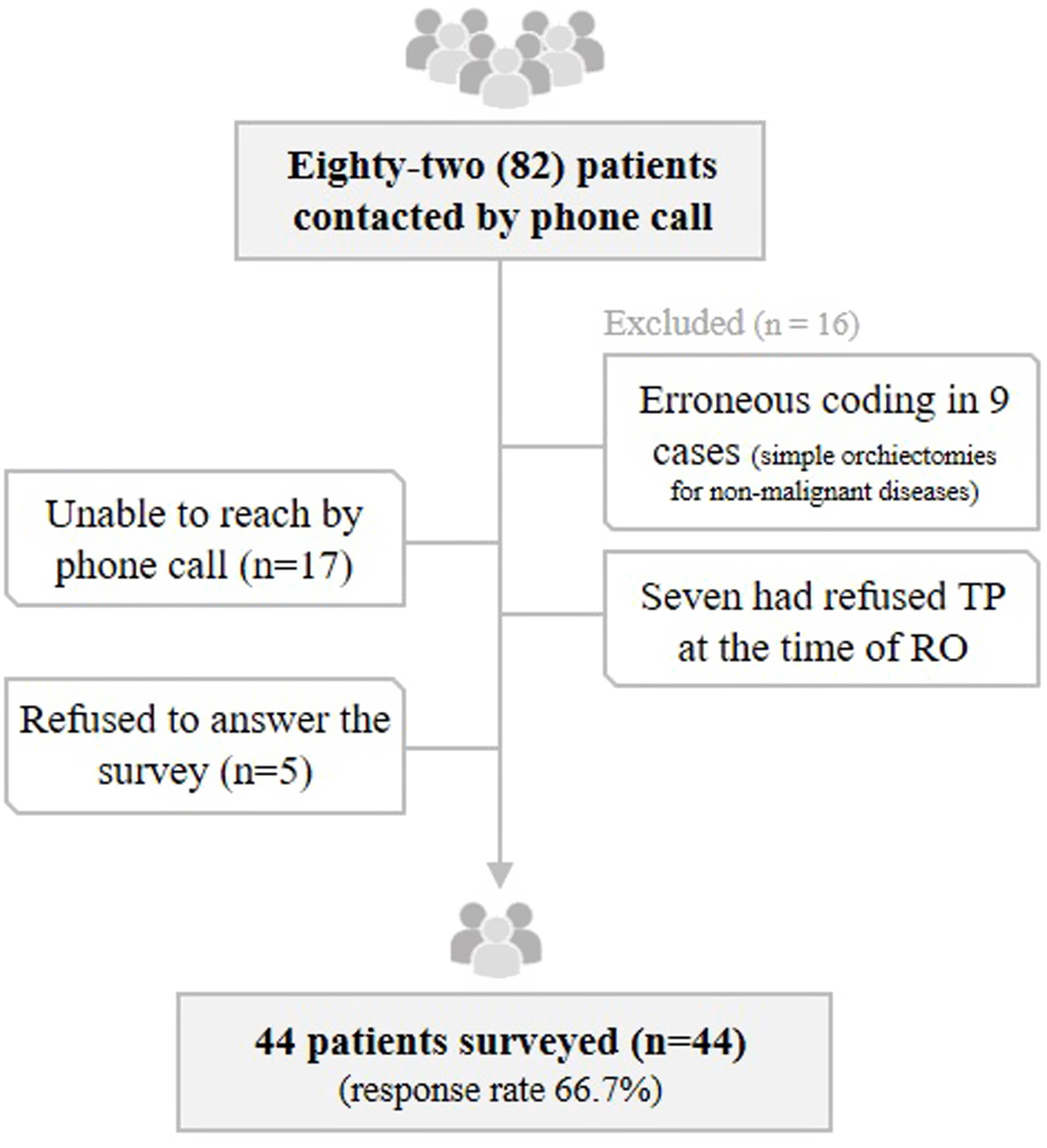

ResultsEighty-two (82) patients were contacted by phone call. Seventeen patients did not answer the phone call despite various attempts, five refused to answer the survey, seven had refused TP, and nine were excluded for erroneous coding (they had been submitted to simple orchiectomy for a non-malignant disease) – Fig. 1. We ended up with a total of 44 patients surveyed, all of them submitted to a unilateral RO. Testicular prosthesis used were silicone gel-filled, manufactured by Polytech Health & Aesthetics®.

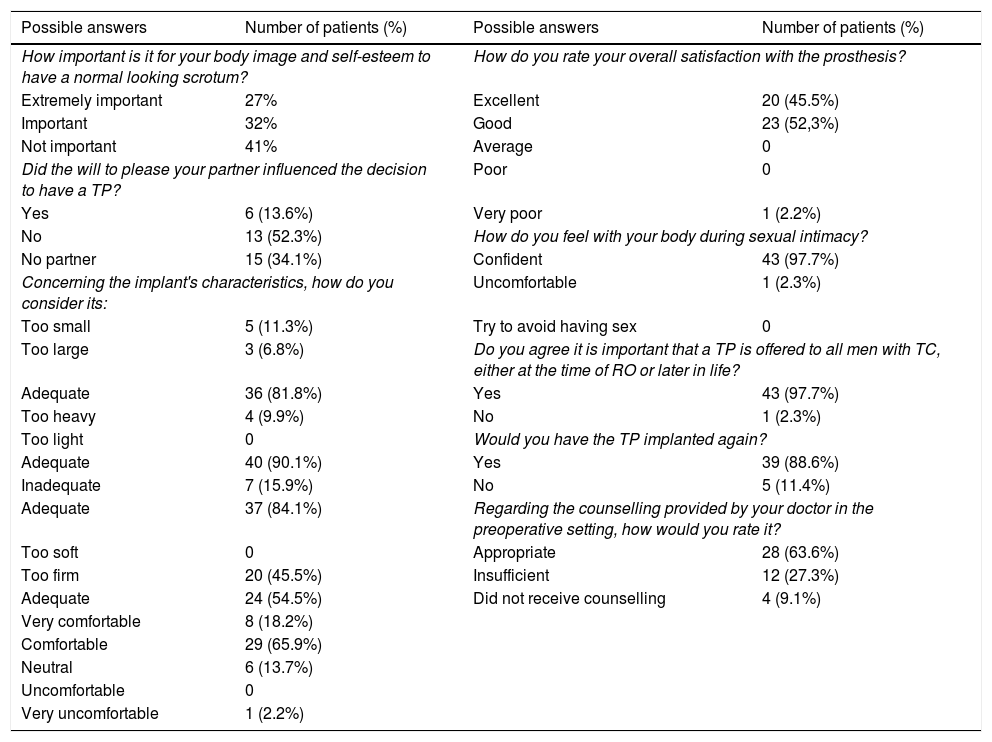

Patients’ mean age at diagnosis was 30.5 years old (range 18–46 years old), 34.1% were single or divorced and the remaining were engaged in a relationship. In all cases the reconstruction was performed at the time of RO. At the time of the interview, patients had the prosthesis for a mean of 43 months (range 14–70 months). The complete survey and detailed answers provided by the patients are detailed in Table 1. Regarding the motivation to have the implant, 26 men (59%) considered that having a normal looking scrotum was either extremely important or important for their body image and self-esteem. Six patients (13.6%) admitted their decision was in part influenced by the will to please their present or future partners. Only 28 men (63.6%) considered they were provided a proper counselling in the preoperative setting. Among the remaining 36.4%, some perceived the prosthesis placement was mainly a doctor's decision, and others either felt the counseling was too abbreviated, not comprehensive, or that they should have been given more time to make a decision.

Survey performed by phone cal to patients submitted to a testicular prosthesis placement after radical orchiectomy (english translation from the original portuguese version) and answers provided by the patients surveyed.

| Possible answers | Number of patients (%) | Possible answers | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How important is it for your body image and self-esteem to have a normal looking scrotum? | How do you rate your overall satisfaction with the prosthesis? | ||

| Extremely important | 27% | Excellent | 20 (45.5%) |

| Important | 32% | Good | 23 (52,3%) |

| Not important | 41% | Average | 0 |

| Did the will to please your partner influenced the decision to have a TP? | Poor | 0 | |

| Yes | 6 (13.6%) | Very poor | 1 (2.2%) |

| No | 13 (52.3%) | How do you feel with your body during sexual intimacy? | |

| No partner | 15 (34.1%) | Confident | 43 (97.7%) |

| Concerning the implant's characteristics, how do you consider its: | Uncomfortable | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Too small | 5 (11.3%) | Try to avoid having sex | 0 |

| Too large | 3 (6.8%) | Do you agree it is important that a TP is offered to all men with TC, either at the time of RO or later in life? | |

| Adequate | 36 (81.8%) | Yes | 43 (97.7%) |

| Too heavy | 4 (9.9%) | No | 1 (2.3%) |

| Too light | 0 | Would you have the TP implanted again? | |

| Adequate | 40 (90.1%) | Yes | 39 (88.6%) |

| Inadequate | 7 (15.9%) | No | 5 (11.4%) |

| Adequate | 37 (84.1%) | Regarding the counselling provided by your doctor in the preoperative setting, how would you rate it? | |

| Too soft | 0 | Appropriate | 28 (63.6%) |

| Too firm | 20 (45.5%) | Insufficient | 12 (27.3%) |

| Adequate | 24 (54.5%) | Did not receive counselling | 4 (9.1%) |

| Very comfortable | 8 (18.2%) | ||

| Comfortable | 29 (65.9%) | ||

| Neutral | 6 (13.7%) | ||

| Uncomfortable | 0 | ||

| Very uncomfortable | 1 (2.2%) | ||

Regarding postoperative complications, one patient (2.2%) underwent TP explanation one month after surgery due to infection and implant's extrusion and two patients (4.5%) had a scrotal hematoma which needed no invasive treatment. No other complications were reported.

The results of the questionnaire showed that the main complaints were related to the implant's size (11.3% and 6.8% considered the implant too small or too large, respectively) and texture, reported as too firm in 45.5%. Weight was deemed adequate in 90.1% and too heavy in the remaining cases. Seven men (15.9%) complained of the implant's position, feeling it was too high in the scrotum, not symmetrical to the contralateral testis. One of these patients eventually decided to have the implant removed, three years later.

The overall satisfaction with the prosthesis was rated as either excellent or good in 97.7% of the patients, and 84.1% deemed it as very comfortable or comfortable. Forty-three men highlighted they feel confident with their body during sexual intimacy, with only one single man expressing unease at the time of a new sexual relationship. Nearly all patients (97.7%) agreed it is important that men with the same disease are given the opportunity to consider a TP, either at the time of RO or later in life. The majority (88.6%) stated they would undergo TP placement again, and 11.4% wished they had declined it.

Discussion & conclusionsNumerous papers raise awareness for the psychological morbidity among TCS.15,16 The identified triggers for that morbidity are anxiety associated with the cancer diagnosis, concerns about fertility, increased sense of vulnerability, uncertainty about the future and fear of social stigmatization.2,17 Furthermore, these patients are usually submitted to a radical orchiectomy (RO). Testicular integrity is recognized as a symbol of virility and at the same time represents what is most vulnerable in male identity.2,15 As so, the loss of a testicle can lead to feelings of shame, unease, and perceived loss of masculinity.2,6–8,15 This rationale gains even more sense in a time of overappreciation of body image and obsessive search for a “perfect body”. Some groups advocate this psychological burden can even have an impact on sexual function.2,8,11,17 Rieker et al. demonstrated that 30% of TCS experienced overall sexual performance distress,18 and more than half of the respondents (61%) in Nichols et al. study stated having one (or no) testicle(s) would affect their sex life.11 Moreover, changes in body image were the factor most strongly related to sexual dysfunction among men submitted to RO in another study.7

Since the first use of a TP in 1941,19 literature reports support it might mitigate the negative impact of a RO, adding more than just a better cosmetic appearance.4,9,10,12,20–22 In the only prospective study available on this matter, Turek et al. assessed, through three validated psychological questionnaires, several parameters of well-being in men with TC, before and after TP placement. Highly statistically significant changes were observed, including improved self-satisfaction and self-esteem, physical attractiveness, and behaviors and feelings during sexual activity.9 Accordingly, Skoogh et al. report long-lasting feelings of loss, uneasiness or shame more commonly in TCS who had not been offered a prosthesis after RO.6 In other studies, the motivations addressed by 50-86.4% of men who elected to receive a TP were the desire to look “normal” and hide the absence of a testis in future sexual relationships, and the concern with cosmetic appearance to others.10,11,20

Our study further reinforces the importance of restoring testicular integrity, with 59% of the patients considering that having a normal looking scrotum was either extremely important or important for their body image and self-esteem. Only a minority (13.6%) admitted that the will to please their sexual partner influenced their decision, which may explain the fact that men in a steady relationship are less likely to want a prosthesis than single men,8 and 65.9% of our patients had a partner at the time of RO.

Regarding the overall satisfaction rate with the prosthesis, 97.7% of the interviewed men were satisfied and 84.1% perceived it as very comfortable or comfortable. Although it could be debatable whether this feedback can change with the type of implant provided, as some characteristics slightly differ between manufacturers, satisfaction rates demonstrated in other studies are consistently high, ranging from 72% to 97% depending on the definition of satisfaction.4,11,19,21,23–25 Also, between 79% and 96% of patients state they would have the procedure again.12,19,22,24,26

Despite these satisfactory rates, some complaints were documented and should be appreciated. The implant's texture was considered too firm by 45.5% of men. Dissatisfaction with prosthetic excessive hardness is a well-established issue in previous publications, reported among 44–86% of TP receivers.13,22,24–26 This highlights the need for improvement in prosthesis’ manufacturing. In our population, the implant's size and position were also deemed inappropriate by 18.1% and 15.9% of the respondents, respectively. These rates are somewhat lower than reported in a recent literature review,13 outlining that approximately a third of TP receivers are unhappy with the implant size and 20–40% believe it is positioned too high in the scrotum.

In our population, only 28 men (63.6%) felt they were provided a proper preoperative counselling. Similarly, in another study 31% of patients believed that their counseling with respect to prosthesis was too short, and 8.5% went as far as to say it was insufficient.26 We believe that the above-mentioned complaints might also be motivated by unrealistic expectations. Men should be given the opportunity to examine an implant sample before the surgery, allowing them to feel the texture, shape and weight, and choose the size they deem appropriate. Involving patients in this process and managing expectations could minimize unsatisfactory feedback. This is a common practice in breast reconstructive surgery in women and should be applied in urology. Most importantly, not all men feel the RO as mutilating, and clinicians should not make unwarranted assumptions as different men have different needs. This is described in detail in the work conducted by Chapple et al., in which reasons to accept and refuse a TP are extensively described.20 Among the interviewed men that refused an implant, some felt that the loss of a testicle was not visibly obvious, did not affect long term self-image or masculinity, or that living with one testicle was comfortable. Others were concerned about the implant's innocuity or were not willing to undergo additional surgery. Similar feedback is described in other papers,6,8,11,22 highlighting that the decision to have a TP is complex and deeply personal.

The timing of the prosthesis placement is another aspect to debate under this matter. All our surveyed patients received it at the time of RO, as it is common practice in our department, in contrast to the low concurrent TP placement rate in other studies.14,27 We advocate this is a good option, as 88.6% of our patients are happy with their decision and stated they would undergo TP placement again. This helps minimize the burden of orchiectomy, obviates the need of a second surgery, and data shows it does not increase complications rate nor delays the beginning of chemotherapy in patients needing it.20,27 In Skoogh et al. study, 64% of those not offered an implant at the time of RO would have liked one if they had been counseled, but in two-thirds their wish for an implant was not enough to warrant a second surgery.6 Moreover, patients might be rushed into accepting an implant under the psychological instability caused by the cancer diagnosis and sudden need to lose a testis. A decision may be best made after all the major medical and surgical treatments are over, when the level of anxiety is lower. By giving them time to cope with the disease and sense how they experience the absence of a testicle, some might realize it has no psychological impact. This rationale is sustained by Chapple et al., who narrate the testimony of some TP receivers who feel “it all happened so fast” and wished they had “more time to think about it”.20 In summary, we believe both practices are valid, as long as patients are offered this option, either at the time of RO or later in life.

One of our study's limitations is the fact that the survey was answered by phone call. It is debatable whether this methodology, also used by Yossepowitch et al.,25 could affect the patients’ ease to provide real answers and lead to biased conclusions, compared to a written survey in which men would not have to directly answer to a doctor. However, it can equally be argued that this strategy is simpler and might enhance the response rate, most importantly from the dissatisfied patients, as it does not demand their time in hospital dislocations or mail replies. This is illustrated by the low response rate to an anonymous questionnaire sent by e-mail in a study conducted by Srivatsav et al.10 Even in studies with a similar methodology and better response rates, it ranges from 55% to 76%.4,12,19,22

The retrospective nature and small number of patients enrolled also hampers the representativity of our results. Also, a comparative group with patients not offered a prosthesis would be useful to assess the implant's benefit on psychological well-being, although this was not possible in our department as all patients are offered a TP by protocol. However, no large multicenter prospective study was ever performed on this subject. Lastly, we found no validated questionnaires to specifically evaluate satisfaction with TP, so the questionnaire we used was developed by our group, bearing in mind it should be simple and not time consuming so we could have a high response rate. Therefore, there is space for future research and for the development of a validated questionnaire to assess the impact and effectiveness of TP implantation. Inclusion of TP counselling in international guidelines’ recommendations should also be considered, so all patients are offered a standardized counselling. Although testicular prosthesis insertion is a cosmetic procedure, it is an important aspect of the long-term health and well-being of men with testicular cancer. To our knowledge this is the first study conducted in our country assessing satisfaction with testicular prosthesis among TCS.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.