In the general population, the current trend is to diagnose Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) at an early stage, which is crucial to improve the prognosis. In contrast, in the Down's syndrome (DS) population, ASD diagnosis is frequently delayed, having negative consequences on the overall development of the children who suffer the condition.

ObjectiveTo identify “early warning signs” for the detection of ASD in DS in the first years of life (0 to 4 years).

MethodsRetrospective cohort study: DS with an ASD diagnosis (DS-ASD) and healthy-DS (DS-noASD) matched by sex and age. Early warning signs were identified and selected from different questionnaires on ASD in the general population: 1. Lack of social smile; 2. lack of shared attention; 3. Lack of seeking comfort/protection; 4. Lack of complaint; 5. Little interest in others; 6. No pointing; 7. Absence of -imitation; 8. Lack of babbling/vocalisation; 9. Inappropriate facial expression; 10. Presence of rituals as repetitive actions or repetitive sentences; 11. Mannerisms hands/fingers; 12. Stereotypies; 13. Lack of sensory interest; and 14. Absence of gaze integration.

Six investigators, who did not participate in the identification of the “early warning signals”, selected those that would guide a diagnosis of ASD (qualitative analysis).

Parents were asked for videos of people with DS in ‘activity’ between 0 and 4 years. The same investigators, blinded to the diagnosis of ASD and after watching the videos, scored the “early warning signals” in three categories: presence/absence/non-evaluable (quantitative analysis).

ResultsDuring 2013, 12 videos of 12 people with SD were obtained: 6 from the SD-ASD group and 6 from the SD-noASD group. The qualitative analysis identified as early warning signals related to the diagnosis of ASD: “Absence of gaze integration”, “absence of imitation”, “presence of rituals as repetitive actions or repetitive sentences” and “stereotypies”, and the quantitative analysis: “lack of shared attention” and “little interest in others”.

ConclusionCertain “warning signs” may lead to a diagnosis of ASD in the first years of life in children with DS.

En la población general, el diagnóstico de trastornos del espectro autista (TEA) se realiza generalmente en una etapa temprana, mejorándose así el pronóstico. En las personas con síndrome de Down (SD), la falta de instrumentos específicos y adaptados para el diagnóstico, y la falta de experiencia de los profesionales, hace que el diagnóstico de TEA suela pasar desapercibido.

ObjetivoIdentificar señales de alarma «tempranas» de un posible diagnóstico de TEA en niños con SD en los primeros años de vida (de 0 a 4 años).

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de cohortes: niños con SD y TEA (SD-TEA) y niños con SD y sin TEA (SD-noTEA) emparejados por sexo y edad. Se identificaron las siguientes señales de alarma tempranas: 1) ausencia de sonrisa social; 2) falta atención compartida; 3) falta de búsqueda de consuelo/protección; 4) ausencia de queja; 5) poco interés por el otro; 6) no señala; 7) no imita; 8) ausencia de balbuceo, vocalización; 9) expresión facial inapropiada; 10) rituales verbales o acciones repetitivas; 11) manierismos manos/dedos; 12) estereotipias; 13) interés sensorial, y 14) no integración de la mirada y la conducta.

Seis investigadores, quienes no participaron en la identificación de las señales de alarma tempranas, seleccionaron aquellas que orientarían a un diagnóstico de TEA (análisis cualitativo).

Se solicitó a los padres videos de las personas con SD en «actividad» entre los 0 y 4 años. Los mismos investigadores, cegados al diagnóstico de TEA y tras visualizar los videos, puntuaron las señales de alarma tempranas en 3 categorías: presencia/ausencia/no evaluable (análisis cuantitativo).

ResultadosDurante el año 2013, se obtuvieron 12 videos de 12 personas con SD: 6 del grupo SD-TEA y 6 del grupo SD-noTEA. El análisis cualitativo identificó como señales de alarma temprana relacionadas con el diagnóstico de TEA: «no integración de la mirada», «no imita», «rituales verbales o acciones repetitivas» y «estereotipias»; y el análisis cuantitativo identificó: «falta de atención compartida» y «falta de interés por el otro».

ConclusiónCiertas «señales de alarma» pueden orientar hacia un diagnóstico de TEA en los primeros años de vida en niños con SD.

Down syndrome (DS) is the principal genetic cause of intellectual disability, caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21 or part of it. The main characteristics of DS are intellectual disability (to very varying degrees), its physical characteristics (flattened nose, macroglossia, small ears, etc.) and psychological disorders (delayed maturation, neuropsychological disorders such as attention deficit, language difficulties and executive functioning issues, amongst others). It is also associated with certain diseases with specific medical needs (heart disease, obstructive sleep apnoea, Alzheimer's disease, etc.). It is estimated that Down's syndrome has a prevalence worldwide of 10 in 10,000 live births.1

The criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) 2 and the International Classification of Diseases Tenth Revision (ICD-10)3 are currently most frequently used for diagnosing Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The DSM-V criteria define ASD as a range of complex neurodevelopmental disorders characterised by social impediments, communication difficulties and stereotyped, restricted and repetitive behaviour patterns. The ICD-10 also includes ASD under Pervasive Developmental Disorders (PDD), defining them as a group of diseases characterised by qualitative disorders of reciprocal social interaction and communication modalities, and as a restricted, stereotyped and repetitive repertoire of interests and activities. Both share the idea that the defining characteristics of the disorder are conditions underlying three main areas of development, social interaction, communication and interests and activities, although the definitions have some differential nuances.

In the general population, the current trend is to diagnose ASD in the first three years of life, since this is crucial to improve its prognosis. By contrast, a diagnosis of ASD in the DS population is often reached very late or even never. Some authors state that ASD can be observed through behavioural characteristics in DS, and can be differentiated from “normal” behavioural patterns in the DS population, such as anxiety and unusual stereotypies.4 Similarly, it has been posited that warning signs to be considered when detecting and diagnosing an ASD in children with DS include poor eye contact and marked clumsiness, along with a tendency towards social withdrawal and repetitive activities.5 Furthermore, the paucity of scientific literature on estimating the prevalence of ASD in people with DS underscores a great global variability, with prevalence ranging from 1% to 12.5%.5–12 Although, methodological differences between studies might explain this variability; these results indicate that a considerable percentage of DS children could develop autism. Therefore, it is important to identify and detect the tendencies proper to ASD in children with DS so that they can be given the appropriate therapy and educational support.5

Because of the impact that ASD might have on children with DS and given the difficulty of diagnosing ASD in this population, our hypothesis is that there are identifiable “warning signs” that would help to diagnose ASD in children with DS. Therefore, the aim of this study is to identify alarm signals in the first years of life of children with DS (from 0 to 4 years), which would lead professionals to suspect a diagnosis of ASD. These alarm signals help to establish guidelines for early action, and can also serve as “markers” for the outcome of ASD.

People and methodsStudy designAn observational, retrospective study carried out in a single centre on a cohort of children with DS diagnosed with ASD and a matched cohort of children with DS with no ASD diagnosis. All the parents (or legal representatives) signed their informed consent to participate in the study. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and Organic Law 15/1999 on personal data protection.

Study populationChildren aged 5 to 10 years from the Centro Médico Down (CMD) (Down's medical centre) were included with or without an ASD diagnosis. Group of children with DS and ASD (DS-ASD): the parents (or legal representatives) of the 10 children with DS and ASD, attended in the CMD, were asked to participate. Group of children with DS and no ASD: DS children, attended in the CMD, were identified matched by age and gender to the DS-ASD group and were asked to participate in the study.

The CMD is a medical centre that was created within the Fundació Catalana Síndrome de Down (Catalan Down's Syndrome Foundation) to meet the specific needs of people with DS. This centre aims to serve as a framework and stimulus for formulating a preventive medical care plan via a coordinated group of general practitioners and specialists devoted to diagnosis, systematic examinations, and prevention and treatment for people with DS.

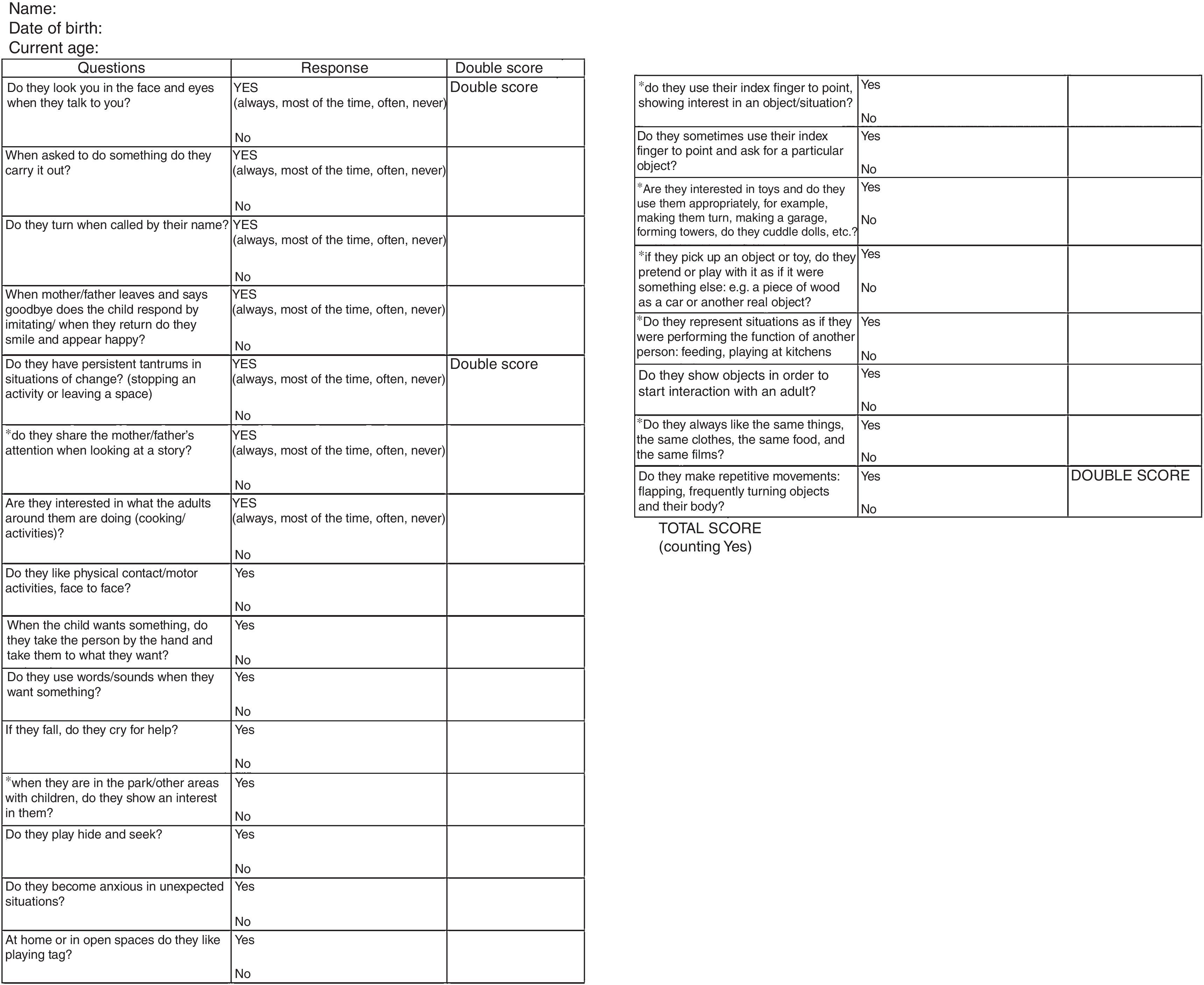

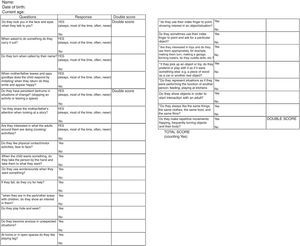

Assessment of ASD: early warning signsDiagnosing ASDA diagnosis of ASD in people with DS was based on the experience and clinical judgement of the CMD's psychologist and neuropaediatrician. Diagnosis was backed up by the semi-structured questionnaire adapted from Dr Viloca's “test for early detection” and given to the parents.6 This questionnaire is shown in Fig. 1. The diagnoses of ASD of all the participants in the study were assessed and their parents or legal representatives were given the questionnaire.

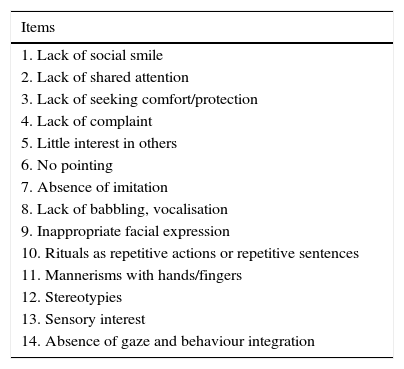

List of early warning signs for diagnosing ASD in people with DSIn order to construct the list of warning signs in people with DS for diagnosing ASD, 3 different types of questionnaires used in the general population for diagnosing ASD were used: ADIR-R, Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) and Dr Viloca's test for the early detection of ASD.

From these, 4 psychology and ASD professionals extracted 14 variables or possible warning signs for diagnosing ASD in children with DS between 0 and <5 years of age. These warning signs are shown and described in Table 1. It was also considered that the warning signs could be assessed using audiovisual material.

Early warning signs selected for diagnosing ASD in children from 0-4 years of age with DS.

| Items |

|---|

| 1. Lack of social smile |

| 2. Lack of shared attention |

| 3. Lack of seeking comfort/protection |

| 4. Lack of complaint |

| 5. Little interest in others |

| 6. No pointing |

| 7. Absence of imitation |

| 8. Lack of babbling, vocalisation |

| 9. Inappropriate facial expression |

| 10. Rituals as repetitive actions or repetitive sentences |

| 11. Mannerisms with hands/fingers |

| 12. Stereotypies |

| 13. Sensory interest |

| 14. Absence of gaze and behaviour integration |

Briefly, the ADIR-R questionnaire comprised a clinical interview enabling in-depth evaluation of typical ASD behaviours focussing on three major areas: language or communication, reciprocal social interactions and restricted, repetitive and stereotyped behaviours and interests. The M-CHAT questionnaire is a screening tool for the early detection of autism symptoms and consists of 23 yes/no questions to be answered by the child's main carer. Finally Dr Viloca's test for early detection of ASD consists of 23 questions with two response options “yes” or “no”. Some of the questions are considered crucial for diagnosis. If the child presents these behaviours, the score is doubled. A score close to 26 implies a possible case of autism, by contrast, if the score is near to 0 we would refer to normal development.

Evaluation of early warning signsSix professionals took part in evaluating the warning signs (evaluators) from the field of psychology: 2 psychologists from the Centro de Desarrollo i Atención Precoz (CDIAP), 2 psychologists from the Centro de Tratamiento Carrilet (Specialists in Autistic Spectrum Disorder), 1 psychologist from the Centro de Salud Mental Infantil y Juvenil (CSMIJ) (Child and Juvenile Mental Health Centres) and 1 Masters student of clinical child psychopathology undergoing an internship.

These 6 evaluators, who did not take part in drawing up the list of “early warning signs”, selected the signs from the list that would best guide a diagnosis of ASD, based on their experience.

All the parents (or legal representatives) who agreed to participate in the study were asked to record a video of the child with DS, at the different ages from 0 to <5 years, showing the person with DS in “action”, for example, during family events such as birthday parties, playing in the park… It was suggested that the video should be between 1 and 2h long. The principal investigator (PI), an expert in DS and ASD, watched all the videos in order to select the sequences of images that might illustrate the objective of the study. Thus, the “study aim” video was created, one video per person of around 15min (maximum 20min). The 6 evaluators reviewed the “study aim” videos twice at separate times (a minimum of one month apart) and each time had to mark “presence” or “absence” or “not assessable” (YES/NO/Not assessable) for the 14 chosen warning signs. The evaluators were blinded to the diagnosis of ASD; in other words, they watched the various videos without knowing whether the DS children had or had not been diagnosed with ASD.

Statistical analysisSample size. No formal calculation of the sample size was made. This was defined as the total number of people with DS diagnosed with ASD attended in the DMD (10 people), and a matched number of people with DS with no diagnosis of ASD (10 people).

A descriptive analysis was made of the study variables. The continuous variables were described as median and range, and the categorical variables as absolute frequencies and percentages.

The reliability of the early warning signs was studied using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and the kappa index. The ICC was used to analyse stability over time (test-retest) and told us that the measurement was stable over time. A 70% correlation would indicate acceptable reliability. The kappa statistical index was used to study the degree of intra- and inter-evaluator agreement. Kappa is a measure of the degree of non- random agreement between evaluators or between measurements of the same variable. The kappa statistical index values were between 0 and 1, 0 indicating a lack of agreement and 1 indicating complete agreement. More specifically, a kappa value of <0.20 was considered “poor” strength of agreement, from 0.21 to 0.40 ‘weak’, from 0.41 to 0.60 ‘moderate’, from 0.61 to 0.80 ‘good’, and from 0.81 to 1.00 ‘very good’.

The validity of the list of early warning signs was assessed by validity of content and its own validity (the validity of the list of warning signs). The validity of content was assessed by the subjective evaluations (opinions) of the evaluators. Thus an attempt was made to assess whether the early warning signs selected were indicators of what was to be measured (early diagnosis of ASD). The validity of the list of warning signs was assessed by exploratory univariate and multivariate logistic regression. Based on the analysis of intra- and inter-evaluator agreement, the variables (early warning signs) were selected in order to start the analysis which enabled us to establish the warning signs p associated with a diagnosis of ASD. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data gathered were recorded on a database programme (Microsoft Access 2010 for Windows, Redmont, CA, U.S.A.). The statistical analysis was conducted using the PASW 19.0 statistical software programme (Chicago, IL, U.S.A.).

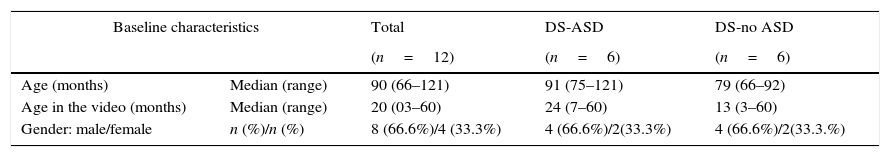

ResultsBaseline characteristicsA total of 14 parents (or legal representatives) provided videos of 14 people with DS. Two of these videos did not meet what was required (one video had no images of the child with DS between 0 and <5 years, and the other had no sequences of images which would illustrate warning signs) and were not included in the analysis. Therefore, 12 videos of 12 people with DS were used to evaluate the warning signs of ASD. Six from the DS-ASD group and 6 from the DS – no ASD group. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the population studied.

Baseline characteristics (DS-ASD: children with DS and a diagnosis of ASD; DS-noASD: children with DS and no diagnosis of ASD).

| Baseline characteristics | Total | DS-ASD | DS-no ASD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=12) | (n=6) | (n=6) | ||

| Age (months) | Median (range) | 90 (66–121) | 91 (75–121) | 79 (66–92) |

| Age in the video (months) | Median (range) | 20 (03–60) | 24 (7–60) | 13 (3–60) |

| Gender: male/female | n (%)/n (%) | 8 (66.6%)/4 (33.3%) | 4 (66.6%)/2(33.3%) | 4 (66.6%)/2(33.3.%) |

DS-ASD: children with DS and diagnosed with an ASD; DS-no ASD: children with DS and with no diagnosis of ASD.

Five of the 6 evaluators (observers) correctly completed the 2 evaluations required of the “study aim” videos and within a minimum of one month between evaluations. One evaluator, in the first assessment, returned their assessment with hardly any score. The procedure to follow was explained to them again and they were asked to reassess the 14 warning signs in the videos. The second score was used for the analysis.

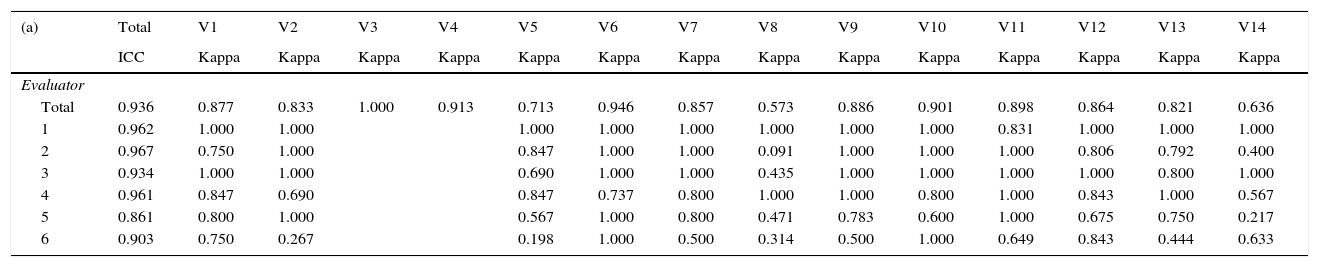

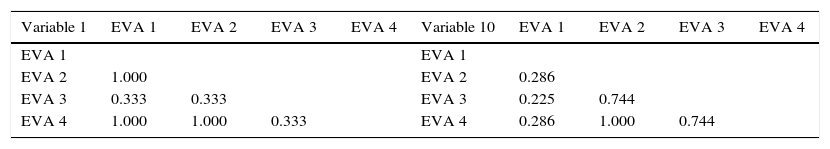

Intra-observer degree of agreement (test-retest). Each evaluator watched the videos twice with a minimum of one month between evaluations, performing 2 evaluation of the 14 warning signs at 2 different times. Table 3a summarises the kappa indices of the intra-observer evaluation, the degree of agreement between the 2 evaluations made by the same evaluator. The warning signs “does not seek consolation/protection” (variable 3) and “does not complain” (variable 4) were assessed by most of the investigators as ‘non-assessable’, i.e., the videos provided did not have sequences where these variables could be assessed. Variables 8 and 14 presented a degree of intra-observer agreement which was considered not to be optimal (in 3 and 2 observers the kappa index was less than 0.05). Evaluator 6 (the student undergoing an internship) presented kappa indices below 0.5 in half (6 out of 12) of the variables. As an analysis of sensitivity, Table 3b summarises the kappa indices of intra-observer assessment, having eliminated the variables that gave no information of whether they might be warning signs (variables 3,4,8 and 14) and observer number 6. It can be seen that evaluator 5 presents lower kappa indices than the other evaluators, overall.

a) intra-observer assessment: kappa indices for each variable; b) intra-observer assessment (kappa indices) having removed variables 3, 4, 8 and 12, and evaluator number 6.

| (a) | Total | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 | V9 | V10 | V11 | V12 | V13 | V14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | |

| Evaluator | |||||||||||||||

| Total | 0.936 | 0.877 | 0.833 | 1.000 | 0.913 | 0.713 | 0.946 | 0.857 | 0.573 | 0.886 | 0.901 | 0.898 | 0.864 | 0.821 | 0.636 |

| 1 | 0.962 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.831 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| 2 | 0.967 | 0.750 | 1.000 | 0.847 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.091 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.806 | 0.792 | 0.400 | ||

| 3 | 0.934 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.690 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.435 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.800 | 1.000 | ||

| 4 | 0.961 | 0.847 | 0.690 | 0.847 | 0.737 | 0.800 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.800 | 1.000 | 0.843 | 1.000 | 0.567 | ||

| 5 | 0.861 | 0.800 | 1.000 | 0.567 | 1.000 | 0.800 | 0.471 | 0.783 | 0.600 | 1.000 | 0.675 | 0.750 | 0.217 | ||

| 6 | 0.903 | 0.750 | 0.267 | 0.198 | 1.000 | 0.500 | 0.314 | 0.500 | 1.000 | 0.649 | 0.843 | 0.444 | 0.633 | ||

| (b) | Total | V1 | V2 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V9 | V10 | V11 | V12 | V13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICC | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | Kappa | |

| Evaluator | |||||||||||

| Total | 0.952 | 0.892 | 0.934 | 0.813 | 0.936 | 0.916 | 0.965 | 0.883 | 0.958 | 0.869 | 0.895 |

| 1 | 0.970 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.831 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 2 | 0.955 | 0.750 | 1.000 | 0.847 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.806 | 0.792 |

| 3 | 0.956 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.690 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 8.000 |

| 4 | 0.950 | 0.847 | 0.690 | 0.847 | 0.737 | 0.800 | 1.000 | 0.800 | 1.000 | 0.843 | 1.000 |

| 5 | 0.901 | 0.800 | 1.000 | 0.567 | 1.000 | 0.806 | 0.783 | 0.600 | 1.000 | 0.675 | 0.705 |

ICC: Intraclass Correlation Coefficient; V: variable.

Degree of inter-evaluator agreement. Based on the results obtained in the degree of inter-evaluator agreement, the degree of inter-evaluator agreement was assessed (Table 4). In this analysis, variables 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 and 14 and evaluators 5 and 6 were not included for the abovementioned reasons. Table 4 shows the inter-observer agreement. There was a total degree of agreement between investigators 2 and 4 (kappa index=1), except in variable 12.

Degree of intra-evaluator agreement (kappa index).

| Variable 1 | EVA 1 | EVA 2 | EVA 3 | EVA 4 | Variable 10 | EVA 1 | EVA 2 | EVA 3 | EVA 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA 1 | EVA 1 | ||||||||

| EVA 2 | 1.000 | EVA 2 | 0.286 | ||||||

| EVA 3 | 0.333 | 0.333 | EVA 3 | 0.225 | 0.744 | ||||

| EVA 4 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.333 | EVA 4 | 0.286 | 1.000 | 0.744 |

| Variable 2 | EVA 1 | EVA 2 | EVA 3 | EVA 4 | Variable 11 | EVA 1 | EVA 2 | EVA 3 | EVA 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA 1 | EVA 1 | ||||||||

| EVA 2 | 0.814 | EVA 2 | 0.438 | ||||||

| EVA 3 | 0.500 | 0.820 | EVA 3 | 0.792 | 0.744 | ||||

| EVA 4 | 0.814 | 1.000 | 0.820 | EVA 4 | 0.438 | 1.000 | 0.744 |

| Variable 5 | EVA 1 | EVA 2 | EVA 3 | EVA 4 | Variable 12 | EVA 1 | EVA 2 | EVA 3 | EVA 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA 1 | EVA 1 | ||||||||

| EVA 2 | 0.847 | EVA 2 | 0.683 | ||||||

| EVA 3 | 0.847 | 0.690 | EVA 3 | 0.833 | 0.824 | ||||

| EVA 4 | 0.847 | 1.000 | 0.690 | EVA 4 | 0.683 | 0.683 | 0.824 |

| Variable 9 | EVA 1 | EVA 2 | EVA 3 | EVA 4 | Variable 13 | EVA 1 | EVA 2 | EVA 3 | EVA 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVA 1 | EVA 1 | ||||||||

| EVA 2 | 0.636 | EVA 2 | 0.636 | ||||||

| EVA 3 | 1.000 | 0.636 | EVA 3 | 0.290 | 0.029 | ||||

| EVA 4 | 0.636 | 1.000 | 0.636 | EVA 4 | 0.636 | 1.000 | 0.029 |

Variables 3, 4, 6, 7, 8 and 14 and evaluators 5 and 6 were not included.

EVA: evaluators.

The 6 investigators, based on their experience and knowledge, assessed the “early warning signs” selected as possible signs for diagnosing ASD in people with DS.

Validity of content. The 6 investigators considered that the 14 warning signs might help in reaching a diagnosis of ASD. There was consensus amongst 4 of them that: “absence of gaze integration “, “absence of imitation”, “presence of rituals as repetitive actions or repetitive sentences” and “stereotypies” would be the most predictive early warning signs.

Validity of predictive warning signs of a diagnosis of ASD. In the univariate analysis, variable 2: ‘lack of shared attention’ (p=0.002), variable 5: ‘little interest in others’ (p=0.029) showed a significant association with a diagnosis of ASD. The multivariate analysis was inconclusive.

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this study is the first to be undertaken in our environment and completed in a population of children with DS with the aim of detecting early warning signs for diagnosing ASD. The results suggest that some early warning signs (2 from the quantitative analysis: “lack of shared attention” and “lack of interest in others”, and 4 from the qualitative analysis: “absence of gaze integration”, “absence of imitation”, “rituals as repetitive actions or repetitive sentences” and “stereotypies”) should make us consider the possibility of a comorbid diagnosis of ASD in children with DS between 0 and <5 years of age. Therefore, given the difficulty of diagnosing ASD in children with DS, these warning signs should be considered in order to achieve an accurate diagnosis of ASD in this population.

Diagnosing ASD in the general population is complicated, but in children with DS, it becomes a much more complex process given their learning disabilities.13,14 Children with DS compared to children of the general population take longer to process stimuli and to respond, but this should not mean they present difficulties in tasks that involve shared attention, or a lack of interest in their social environment. Furthermore, at present there is no consensus as to how to act if ASD is suspected in children with DS; in other words, there is no protocol for diagnosis, and this, amongst other things, delays the age at which DS children are diagnosed.15 In the CMD, the procedure for diagnosing ASD in DS children is based on the experience and clinical judgement of the centre's psychologist and neuropaediatrician, backed up by structured interviews with their parents (or legal representatives). In addition to the lack of a diagnosis protocol, many professionals do not feel that they are sufficiently prepared to detect the condition in these children. This all makes reaching a diagnosis of ASD in children with DS even more difficult. This might explain in part why professionals a priori take early warning signs (validity of content) into account other than those obtained in quantitative analysis (validity of predictive warning signs of an ASD diagnosis).

The limited size of the sample in this study might also explain the results obtained for both the reliability and the validity of the list of early warning signs evaluated. At the time of drafting the protocol, the implications of the limited number available of children with DS diagnosed with ASD had already been assessed (a maximum of 10). In other words, we were aware that this fact would limit our obtaining conclusive results. Given this scenario, and given the lack of consensus for diagnosing ASD in children with DS, this first study was considered a single-centre study seeking to limit variability in terms of diagnosis. Nonetheless, both facts, the reduced sample size and the single-centre design, make it conceivable that some relevant warning signs for diagnosing an ASD in children with DS are being undervalued. This limits the possibility of generalising the results obtained to other populations of children with DS.

Although home videos are good research tools for analysing and studying the signs of ASD,16 in our case, not all the videos showing the person with DS in ‘action’ (at family events such as birthday parties, playing in the park…) served to assess all the possible warning signs under study. In the videos the evaluators could not see two (14%) early warning signs out of the 14 considered, “lack of seeking comfort/protection” (variable 3) and “lack of complaint” (variable 4). Therefore, the “study aim” audiovisual material “, based on unstructured and uncontrolled home videos made it difficult to detect behaviours characteristic of ASD. In a clinical situation the child would be assessed using specific demands directed at confirming or ruling out a diagnosis. In future studies, the parents (or legal representatives) should be given instructions or examples to ensure that the audiovisual material made at home would be useful for assessing a possible ASD. Similarly, the results obtained also suggest that the early warning signs of ASD appear easier to observe between 2 and 4 years of age in children with DS. This result might be associated with the fact that the audiovisual material provided showed the activities of these children in this age group. A future objective would be to detect warning signs between 0 and 2 years of age, since this is crucial for improving prognosis.

Therefore, based on the experience gained, future studies should be prospective, multicentre, with a larger sample size and with a diagnosis of ASD in children with DS agreed or assessed using the specific test for diagnosing ASD, “Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2)”. Similarly, instructions should be drawn up about the audiovisual material to be provided by parents (or legal representatives), and thus gather structured and controlled situations. Therefore, action guidelines would be provided with regard to the audiovisual material, unifying the information gathered and ensuring that it is assessable and comparable. In addition, each participant should be asked for at least 4 videos, one video for each year of the child's life from 0 to 4, i.e., one video from 0 to 1 year, another from 1 to 2 years, another from 2 to 3 years and the last video from 3 to 4 years of age.

In sum, despite the abovementioned limitations, the following should be considered in reaching a conclusion: 1) the lack of a protocol for diagnosing ASD in children with DS, 2) the study design (descriptive), 3) the sample size, 4) single-centre study, 5) the quality of the videos; the results obtained might be over or underestimated. This study suggests the existence of early warning signs which might indicate a diagnosis of ASD in the first years of life in children with DS. This does not mean that an ASD should be diagnosed in a child with DS who presents any one of these early warning signs. If an ASD is suspected, it is important to pay special attention to the child (and their family) and provide appropriate follow-up. This is the basis for more precise and timely diagnosis and intervention, and to establish the appropriate therapeutic guidelines. 7

Financial resourcesThis study was funded by a grant from the Fundació Catalana Síndrome de Down.

Contribution of authorshipB. Ortiz and S. Videla designed and wrote the study protocol; B. Ortiz assessed the children with DS and collected and reviewed the home videos; B. Alcacer, D. Torres, I. Jover, E. Sánchez, M. Iglesias and L. Videla marked the audiovisual material J. Fortea, S. Videla and I. Gich were in charge of the statistical analysis of the data; B. Ortiz, L. Videla and S. Videla drafted the article. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To Dr. A. Nacimento, neuropaediatrician at CMD, for his participation in diagnosing ASD in children with DS. Special acknowledgement goes to the people with Down's syndrome and their parents and carers who made it possible to undertake this study, and all the professionals involved in assessing the warning signs and watching the audiovisual material. Particular thanks go to Beatriz Garvía, clinical psychologist at CMD and the Servei d’Atenció Terapèutica (SAT) of FCSD for her collaboration in reviewing the list of warning signs. We also want to give special mention to the daily effort and dedication on the part of the Fundació Catalana Síndrome de Down in their work in improving the quality of life of people with Down's syndrome and in the protection of their human rights.