Cleft lip and palate is a congenital malformation which can affect breathing, swallowing, language articulation, audition and voice. These patients show an insuffi cient maxillary growth and a class III skeletal malocclusion due to maxillary retrusion. Orthopedic treatment of the unilateral cleft lip and cleft palate patient by means of a facemask during the right time can stimulate maxillary growth. This study reviewed 90 clinical charts (pre and post treatment) of patients with complete unilateral cleft lip and cleft palate, treated from 1996 to 2007 with rapid palatal expansion through an occlusal acrylic plate and facemask at the Orthodontic Department, General Hospital «Dr. Manuel Gea González» in Mexico City. To evaluate the sagittal and vertical maxillomandibular change the student’s T test, Wilcoxon test and χ2 test (SPSS v.10) were used. Our results show that the use of this appliance increases vertical dimension and reduces maxillomandibular discrepancy due to downward and forward growth of the maxilla.

El labio y paladar hendidos es una malformación congénita que puede afectar los mecanismos respiratorios, deglutorios, articulatorios, del lenguaje, la audición y la voz. A los pacientes que les falta un crecimiento maxilar adecuado presentan una relación esquelética maxilomandibular clase III por retrusión maxilar. El tratamiento ortopédico con máscara facial en estos pacientes con secuela de labio y paladar hendidos unilaterales durante un periodo adecuado puede estimular y redirigir el crecimiento del maxilar. En este trabajo se estudiaron 90 expedientes (antes y después del tratamiento) de pacientes con secuela de labio y paladar hendidos unilaterales completos (fi sura labio-alveolo-palatino) que fueron atendidos en la División de Estomatología-Ortodoncia del Hospital General «Dr. Manuel Gea González» durante los años de 1996 a 2007, y que fueron tratados con máscara de protracción facial con apoyo frontomentoniano y un aparato intraoral con un tornillo de expansión rápida palatina con caras oclusales de acrílico. Para evaluar los cambios maxilares en sentido anteroposterior y vertical. Se utilizó la prueba t de Wilcoxon y χ2 (SPSS v.10). Se concluyó que el uso de la máscara facial en estos pacientes aumenta la dimensión vertical y reduce la discrepancia maxilomandibular por una estimulación del crecimiento maxilar hacia abajo y adelante.

Cleft lip and palate is a congenital anomaly whose incidence in Mexico is 1:850 newly live births. It may affect respiration, deglution, articulations, language, hearing, and the voice. This malformation has significant impact not only on an aesthetic level, but also at a social level. It is also a major public health problem. Generally, these patients lack adequate maxillary growth and have a skeletal class III relationship due to maxillary retrusion. The problem may be increased depending on the type of lip-alveolar-palate cleft and the severity of the scarring. Rehabilitation of this anomaly requires a multidisciplinary work by performing surgical interventions during the various growth stages of the patient, thus affecting growth of the related structures. Orthopedic treatment with face mask in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae during an appropriate period can stimulate and redirect the growth of the maxilla, obtaining vertical and anteroposterior changes in both dimension and position. By improving the facial profi le the complexity or even the surgical need can be reduced.

Anterior cross bite can be corrected with three to four months of maxillary expansion and protraction, depending on the severity of the malocclusion. The improvement of the overbite and molar ratio can be obtained with four to six additional months of maxillary protraction. In a clinical trial, overjet or overbite correction was the result of the forward movement of the maxilla (31%), posterior positioning of the mandible (21%), labial movement of the upper incisors (21%), lingual movement of the lower incisors (20%). Molar relationship was corrected to a class I or class II relationship through a combination of skeletal movements and differential movements of the upper and lower molars. Anchorage loss was observed by the mesial movement of the upper molars during maxillary protraction. Overbite was improved by the eruption of the upper and lower molars. Total facial height was increased because of the downward movement of the maxilla, the downward rotation of the maxilla and the rearward movement of the mandible.1

Patients with class III skeletal malocclusion often present a concave facial profile, a retrusive nasomaxillary area and a prominent facial lower third. The lower lip protrudes often in relation to the upper lip. Treatment with expansion and maxillary protraction can correct the facial profiles of the skeletal and soft tissue, as well as improve the position of the lips. These changes often lead to dental compensation.

Ngan (1997) studied patients treated with eight months of protraction maxillary. The maxilla moved an average of 2.1mm. In control patients without treatment there was only a 0.5mm maxillary advancement. On average, with treatment the mandible was positioned 1.0mm back, and without treatment it advanced 1.7mm. In addition, without treatment, the incisors compensated the skeletal discrepancy by upper incisor proclination and retroinclination of the lower incisors.1

Patients with cleft lip and palate sequelae often exhibit a skeletal deficiency of the maxilla, which results in anterior or posterior crossbite unilateral or bilateral. In cases of maxillary discrepancy, the forward and down position of the maxilla should improve occlusion and profi le. Therefore, orthopedic treatment with maxillary protraction by means of a facial mask has been recommended by more than two decades. However, many studies of protraction in orthopedic patients with cleft lip and palate sequelae have been based on case reports and small groups. In addition there are no studies of the vertical change with the use of a face mask.2–5

Cephalometrically, the sagittal maxillo-mandibular relationship can be assessed by angular variables; for example, ANB angle (angle that measures the line drawn from the more posterior point of the anterior concavity profile of the maxillary bone; the more anterior point of the frontonasal suture and the most posterior point of the anterior concavity of the anterior edge of the mandible).

In 1977, Hasund studied Norwegian children with normal occlusion; he found an ANB of -4.5 to 8.5 degrees (average 2.5 degrees). Tindlund (1993) found an ANB from 3.5 to 4.6 degrees in patients from six to nine years of age. Holdaway (1956) and Hasund (1977) mentioned that an ANB of 0 to 4 degrees is considered a favorable value after puberty.6–9

Tindlund (1994) studied horizontal changes of the maxilla after the orthopedic use of protraction in 72 patients with cleft lip and palate sequelae before 10 years of age. It was found that in the favorable group (63% of the total cases), presented an increased ANB (3.3 degrees), maxillary advancement (1.8mm) and the upper teeth advanced (3.6mm).10 Gavidia (1997) studied the orthopaedic appliance that has a cap of the premaxilla and cranial support to produce positional changes of the premaxilla and found that it acted by inhibiting vertical growth of the premaxilla, and that causes retrusion in an anteroposterior direction, so that the appliance complied with the intended purpose.11

MethodsThis study was a comparative (before and after), open, observational, retrospective and longitudinal study. We assessed 90 cases of patients with a complete unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae who were treated at the Stomathology-Orthodontics Division of the General Hospital «Dr. Manuel Gea González» during the years 1996 to 2007, and treated with protraction facial mask that consisted in an appliance of rapid palatal expansion with acrylic on the occlusal face (Figure 1). To assess the changes in the maxilla in an anteroposterior and vertical direction with the use of facial mask in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae taking as baseline references the following values:

In an horizontal direction; the following are valued:

- 1.

Maxillary position

- •

SNA (Steiner): is the angle formed by the sella- nasion and Nasion-A point (N-A). Planes (S-N) standard value is 82°.

- •

Maxillary convexity (Ricketts): is the distance between point A and facial plane (N-PG). Standard value is 2.0mm at the age of 8.5 years. Decreases 0.2mm per year.

- •

Maxillary depth (Ricketts): is the angle formed by the Frankfort plane and the N-A plane. Standard value is 90°±3°.

- •

Anterior cranial length (Ricketts): is the distance between center of skull and Nasion. Value of the standard is 55mm±2.5mm.

- •

- 2.

Maxillomandibular relationship

- •

ANB (Steiner): is the angle formed by the planes sella-Nasion planes (S-N) and Nasion-Point B (NB). Standard value is 2°.

- •

Facial convexity (Jarabak): is formed by the intersection of the plane N-A and the A plane- Pg. Negative values (flat TO-Pg ahead of N-A) indicate profiles concaves (class III). Positive values (flat TO-Pg behind N-A) indicate convex profiles (class II).

- •

- 3.

Maxillary size

- •

Effective maxillary length (Co-A) (McNamara): is the distance between the most upper and posterior portion of the condyle (Co) and the maximum concavity of the maxillary contour (point A). Normal values in women are 91.0mm±4.3mm; for males it is 99.8mm±6.0mm.

- •

Vertically; the vertical dimension of the maxilla was assessed with the following values:

- •

Maxillary height (N-Fc-A): is angle formed by the Nasion FC-A planes. Normal value is 53° at age 8.5. It increases 0.4° per year±3.0°.

- •

Posterior facial height (Bigerstaff): distance between the frontal-ethmosphenoid suture (Se) and the most posterior point of the posterior nasal spine (PNS). The normal value is 54.7±4.4mm.

- •

Upper anterior facial height (Bigerstaff): is the distance between Nasion point (N) and the anterior nasal spine (ANS). Normal value is 59.7mm±3.9mm.

- •

Lower anterior facial height (Bigerstaff): distance between the anterior nasal spine (ANS) and menthon (Me). Normal value is 79.5mm±6.2mm.

- •

Posterior facial height (Bigerstaff): is the distance between Sella point (S) and Gonion point (Go). Normal value is 88.2mm±5.9mm.

- •

Anterior facial height (Bigerstaff): is the distance between Nasion point (N) and the point Menthon (Me). Normal value is 136.8mm±7.9mm.

In each of the sequences and by each one of the measurements, averages were obtained before and after treatment, the overall percentages of favorable and unfavorable changes by sex and age groups. Additionally, the percentage of pre- and post-treatment measurements thatwerewithinthenorm (see normal values for measurements in the introduction) and out of it, classifying the measurements as low, normal and high. To assess whether the changes in the obtained averages were significant the t test for paired samples was used. In the cases where restrictions were found, the Wilcoxon test was performed; and for percentile differences, the χ2 test. The statistical package SPSS v10 was used for the data analysis.

With regard to the study of Tindlund (1994), if the difference between the pre- and post-treatment values is equal to or more than 1.5 degrees or millimeters, the patients were classified as positive group. If the difference between the pre- and post-treatment values were less than 1.5 degrees or millimeters, the patients were classified as an unfavorable group.10

The expected change as successful response to treatment was that the dimensions should increase.

The cephalometric norm was used for measurements. These were made in the form directly on standardized lateral head films, taken by a single radiology and image laboratory, before facemask use and at the end of the study. The units of measure were in degrees and in millimeters.

ResultsFrom the total study sample 45 (50%) were males and 45 (50%) females. Forty-teo (46.7%) patients presented right unilateral cleft lip palate sequelae and 48 (53.3%) on the left side.

The average initial age of in the sample was 8.11 years (standard deviation [SD] 1.9, confidence interval [CI] 95%: 7.7-8.5), and at the end of the study it was 11.15 years (SD 2.0, 95% CI: 10.7-11.6). No significant differences were found in the average age by sex or by type of cleft lip and palate sequelae in the pre or post treatment.

For the information analysis, patients were grouped on the basis of response to orthopedic treatment. I was considered that all patients that showed a change equal to or greater than 1.5 degrees or millimeters in relation to the initial value had a favorable response, otherwise, it was described as an unfavorable response. In addition, ages were grouped as follows, 6 to 7 years (47.8%), 8 to 9 years (30%) and 10 to 14 years (22.2%), with the purpose of studying the changes in age structure, under the assumption that a favorable response would be greater in the first two age groups, in view of the fact that these groups are in full growth and development.

Vertical planeIn table I the averages of pre and post-treatment measurements in the vertical plane can be seen. Posttreatment averages in all the measurements were higher than the pretreatment average, thus showing a strong statistical significance in the difference to a level less than .001 in all values. It was also noted that the percentage of the differences in the pre- and postoperative averages ranged in an increase between 8.0 and 9.6% taking as reference the pretreatment value.

Pre and post-treatment average of the vertical measurements.

| Measurements | Average | S.D. | Confidence interval (95%) | Paired t test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | ||||

| Alantsu | |||||

| Pre | 47.9 | 3.9 | 47.1 | 48.8 | ---- |

| Post | 51.7 | 3.9 | 50.9 | 52.5 | ---- |

| Diference | 3.8 (8.0%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | < 0.001 |

| Alantin | |||||

| Pre | 65.3 | 5.8 | 64.1 | 66.5 | ---- |

| Post | 71.4 | 6.0 | 70.2 | 72.7 | ---- |

| Diference | 6.1 (9.3%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | < 0.001 |

| Alpossu | |||||

| Pre | 39.7 | 4.6 | 38.7 | 40.6 | ---- |

| Post | 43.5 | 4.5 | 42.5 | 44.4 | ---- |

| Diference | 3.8 (9.6%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | < 0.001 |

| Alfacon | |||||

| Pre | 111.4 | 7.4 | 109.8 | 113.0 | ---- |

| Post | 120.7 | 7.5 | 119.1 | 122.3 | ---- |

| Diference | 9.3 (8.4%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | < 0.001 |

| Alfacpo | |||||

| Pre | 67.9 | 5.8 | 66.6 | 69.1 | ---- |

| Post | 73.8 | 6.1 | 72.6 | 75.1 | ---- |

| Diference | 6.0 (8.8%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | < 0.001 |

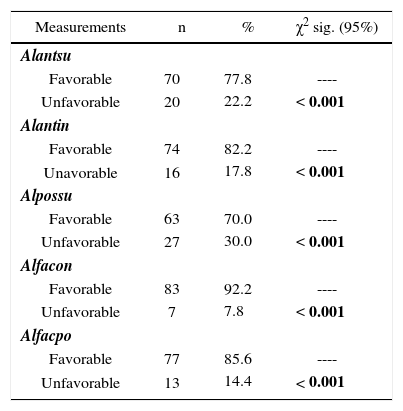

In table II, it can be seen that in all measurements of the vertical plane a positive response was obtained in a high percentage, that is to say, between 70 to 92.2% of the patients had an increase of 1.5mm or greater in the five vertical dimensions. The χ2 test shows that the difference of favorable responses versus the unfavorable responses is significant at a level less than .001.

Treatment response according to the type of vertical measurement.

| Measurements | n | % | χ2 sig. (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alantsu | |||

| Favorable | 70 | 77.8 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 20 | 22.2 | < 0.001 |

| Alantin | |||

| Favorable | 74 | 82.2 | ---- |

| Unavorable | 16 | 17.8 | < 0.001 |

| Alpossu | |||

| Favorable | 63 | 70.0 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 27 | 30.0 | < 0.001 |

| Alfacon | |||

| Favorable | 83 | 92.2 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 7 | 7.8 | < 0.001 |

| Alfacpo | |||

| Favorable | 77 | 85.6 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 13 | 14.4 | < 0.001 |

Table III presents the percentage of vertical measurements that were within normal standards and above or below the same, in both pre and posttreatment results. In the table, it can be observed in all measurements the percentage decline that was low in the pretreatment phase and directly proportional increase in the ones that were classified as normal. The χ2 assessed differences between the percentages of the two moments, before and after, showed a significant statistical significance to a level less than .001. That is to say, the response to treatment allowed that a significant percentage of individuals reached normal parameters in the vertical dimension, ranging from 8.3 to 23.3% of the individuals.

Classification of facial vertical measurements in relation to normal values.

| Measuraments | Pretreatment | Post-treatment | Percentile difference | χ2 sig. (95%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| NOMALAN1 | ||||||

| Low | 89 | 98.9 | 78 | 86.7 | -12.2 | < 0.001 |

| Normal | 1 | 1.1 | 12 | 13.3 | 12.2 | < 0.001 |

| NOMALAI1 | ||||||

| Low | 81 | 90.0 | 60 | 66.7 | -23.3 | < 0.001 |

| Normal | 9 | 10.0 | 30 | 33.3 | 23.3 | < 0.001 |

| NOMALFP1 | ||||||

| Low | 90 | 100.0 | 82 | 91.1 | -8.9 | < 0.001 |

| Normal | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 8.9 | 8.9 | < 0.001 |

| NOMALFC1 | ||||||

| Low | 89 | 98.9 | 76 | 84.4 | -14.5 | < 0.001 |

| Normal | 1 | 1.1 | 14 | 15.6 | 14.5 | < 0.001 |

It should be noted that the results by age groups had no significant statistical differences, nor in the pre-treatment and post-treatment averages nor in the favorable or unfavorable response, although it is important to point out that the averages and percentages were slightly higher in the 6 to 9 years groups compared to the group of 10 or more years of age.

Sagittal plane and maxillary lengthTable IV presents the results of the pretreatment and post-treatment measurements in the sagittal plane. Instead of what happened on the vertical plane, in this plane significant changes in the average were observed only in SNA, anterior cranial length and maxillary convexity. The percentile difference between the pre and post-treatment average was highly variable, ranging even from negative values, -0.4% in maxillary depth and up to 33% in maxillary convexity.

Pre and post-treatment average of the sagittal measurements and maxillary length.

| Measuraments | Average | S.D. | Confidence interval (95%) | Paired t test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | ||||

| Sna | |||||

| Pre | 77.8 | 4.3 | 76.9 | 78.7 | ---- |

| Post | 78.8 | 3.9 | 78.0 | 79.6 | ---- |

| Difference | 1.0 (1.2%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | 0.021 (.041)* |

| Maxillary convexity | |||||

| Pre | 1.8 | 3.2 | 1.1 | 2.5 | ---- |

| Post | 2.4 | 3.4 | 1.7 | 3.1 | ---- |

| Difference | 0.6 (33.3%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | 0.058 (.046)* |

| Maxillary depth | |||||

| Pre | 87.7 | 3.9 | 86.9 | 88.5 | |

| Post | 87.4 | 3.9 | 86.6 | 88.2 | |

| Difference | -0.3 (-0.4%) | 0.469 (.678)* | |||

| Anb | |||||

| Pre | 2.2 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 2.8 | ---- |

| Post | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 3.3 | ---- |

| Difference | 0.5 (21.2%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | 0.162 (.144)* |

| Convac | |||||

| Pre | 7.9 | 18.1 | 4.1 | 11.7 | |

| Post | 8.2 | 17.2 | 4.6 | 11.8 | |

| Difference | 0.2 (3.0%) | 0.738 (.762)* | |||

| Cranial length | |||||

| Pre | 52.1 | 3.5 | 51.4 | 52.8 | ---- |

| Post | 54.6 | 3.4 | 53.9 | 55.3 | |

| Difference | 2.5 (4.7%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | < 0.001** |

| Maxillary length | |||||

| Pre | 80.0 | 6.0 | 78.7 | 81.3 | ----- |

| Post | 84.6 | 6.0 | 83.3 | 85.9 | ----- |

| Difference | 4.6 (5.8%) | ---- | ---- | ---- | < 0.001** |

In relation to the maxillary length, whose pre and post-treatment averages can also be seen in table IV, it shows a statistically significant difference to a level of .001, with a 5.8% increase of the average.

Table V confirms the variability found in the previous table of results. In the sagittal plane the responses considered as unfavorable or less than 1.5 degrees were higher (between 55.6 and 63.3%) to those that were favorable, except for anterior cranial length that obtained 57.8% of a favorable response.

Response to treatment according to the sagittal measurement and maxillary length.

| Measurements | n | % | χ2 sig. (95%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sna | |||

| Favorable | 38 | 42.2 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 52 | 57.8 | 0.140 |

| Convmax | |||

| Favorable | 36 | 40.0 | ---- |

| Desfavorable | 54 | 60.0 | 0.058 |

| Profmax | |||

| Favorable | 34 | 37.8 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 56 | 62.2 | 0.020 |

| Anb | |||

| Favorable | 33 | 36.7 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 57 | 63.3 | 0.011 |

| Convac | |||

| Favorable | 40 | 44.4 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 50 | 55.6 | 0.292 |

| Longcra | |||

| Favorable | 52 | 57.8 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 38 | 42.2 | 0.140 |

| Maxillary length | |||

| Favorable | 66 | 73.3 | ---- |

| Unfavorable | 24 | 26.7 | < 0.001 |

For maxillary length, favorable response was majority in 73.3% of the patients (Figure 2).

DiscussionEarly orthopedic treatment with the use of the protraction facial mask has been recommended to treat retrusion of the facial middle third in patients with cleft lip and palate sequelae. Several clinical studies have shown the favorable effect of stimulating maxillary growth when it begins in the stage of early mixed dentition (Ishikawa et al., 1996; Irie and Nakamura, 1975; Ryghy Tindlund, 1982),2,3,12 since growth of perimaxillary sutures is active (Bjork, 1966)13 from before the age of 12 years and according to Delaire et al. (1976)14 before 9 years of age.

The results of this study agree with those of Delaire.14 They show greater maxillary changes in groups of 6 to 9 years.

On the sagittal plane, the results reported in this study vary with the results of previous studies (Rygh and Tindlund, 1982; Delaire et al., 1976; Subtelny, 1980).3,14,15 This diversity in results may be due to multiple factors; for example, the variability of the skeletal disorders or its severity, patient cooperation, the frequency of broken appliances, etc.

According to Bergland (1967),16 another important factor is the effect of cleft lip and palate scarring which can modify the effect of the appliance.

However, there were no significant differences with what has been reported in the literature in the studies of Sarnas and Rune (1987),17 who studied 7 patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae. Additionally, it was found that the total answers considered as unfavorable or less than 1.5 degrees were higher (between 55.6 to 63.3%) to those that were favorable.

Our study showed a favorable change in SNA of 42.2% in 90 cases, compared with the study of Tindlund (1994)4 where a favorable change was present in 63% of 72 cases and Ranta (1989)18 who showed SNA increase only in 5 cases out of 14.

For maxillary length the favorable response was statistically significant (p < .001), in 73.3% of the patients (the average of the change was from 4.6mm) compared to the study of Tindlund (1994)4 that presented an average 1.8mm. This discrepancy in results suggests sufficient changes in the mandible to establish a future research line.

All patients in the pretreatment period showed a vertical growth deficiency of the maxilla. After treatment with the protraction face mask, the posttreatment average of the vertical measurements of the maxilla and the mandible was higher than pretreatment average (from 3.8 to 9.3mm); showing a strong statistical significance in the difference (p < .001) thus showing that the significant change was positive in 70-92.2% (p < .001). Buschang et al. (1994)19 studied 21 patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate sequelae and found that the vertical increase was only in the mandibular vertical dimension.

ConclusionsFace mask use in growing patients with cleft lip and palate sequelae increases vertical dimension and reduces the maxillomandibular discrepancy by a downward and forward stimulation of maxillary growth.

The end result also depends on individual factors: genetic pattern, the management of the cleft lip and cleft palate, the functional change that results from correct biomechanics, patient’s cooperation or the combination of these factors.

It should be borne in mind that this treatment is only the first stage; in most cases an individualized orthodontic treatment is necessary or even orthognathic surgery to ensure an optimal result.