To assess the dietary quality of preschool children in the urban area of Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil.

MethodsDietary quality was measured according to the Healthy Eating Index (HEI), adapted to Brazil. Food consumption was obtained using the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ). The index score was obtained by a score, ranging from 0 to 100, distributed in 13 food groups that characterize different components of a healthy diet. The better the quality of the diet, the closer the score is to 100.

ResultsDietary quality was evaluated in 556 preschoolers. The mean HEI score value was 74.4 points, indicating that diets need improvement. The mean scores were significantly higher among girls and in children from families with income between one and less than three minimum wages.

ConclusionsThe children showed vegetable consumption below the recommended level, while foods of the food group of oils and fats, as well as the group of sugars, candies, chocolates and snacks, were consumed in excess. It is important to reinforce guidelines to promote healthier eating habits, which may persist later in life.

Avaliar a qualidade da dieta de pré-escolares residentes na área urbana da cidade de Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.

MétodosA qualidade da dieta foi avaliada de acordo com o Índice de Alimentação Saudável (IAS), adaptado para o Brasil. O consumo alimentar foi medido por meio de Questionário de Frequência Alimentar. O escore do índice foi obtido por uma pontuação distribuída em 13 grupos alimentares, que caracterizam diferentes aspectos de uma dieta saudável, variação de 0 a 100 pontos. Quanto mais próximo de 100, melhor será a qualidade da dieta.

ResultadosA qualidade da dieta foi avaliada em 556 pré-escolares. O valor médio do escore do IAS foi de 74,4 pontos. Isso indica que as dietas necessitam ser melhoradas. As médias dos escores foram significativamente maiores entre as meninas e entre crianças provenientes de famílias com renda familiar entre um e menos de três salários mínimos mensais.

ConclusõesAs crianças apresentaram consumo de verduras e legumes abaixo da recomendação, enquanto os alimentos do grupo dos óleos e gorduras, bem como do grupo dos açúcares, balas, chocolates e salgadinhos, foram consumidos em excesso. É importante reforçar orientações para promover um hábito alimentar mais saudável, que poderá perdurar em etapas posteriores da vida.

Adequate nutrition in childhood has an impact on the child's growth and physiological development, health and welfare. At this phase, a balanced diet becomes very important, as they are going through a phase of growth, development, and formation of personality and eating habits.1

Parents influence the development of their children's eating habits, as they are responsible for the process of introducing foods, the dietary pattern offered to the child and their attitudes toward food.2 Children's food preferences are learned from repeated experiences during the consumption of certain foods. These habits have an effect on their food intake, subject to the physiological consequences and the social context in which the child lives. In this phase they prefer high-calorie foods, as they bring greater satiety and ensure the necessary energy supply for basic needs.3

In the last few decades, the population's food quality has been evaluated through dietary indexes. These consist of a food analysis method aiming to determine its quality through one or more parameters simultaneously: adequate nutrient intake, number of servings consumed by each food group and the amount of different food items present in the diet.4 Most of these indices were developed in the United States, and are being adapted and used in other countries.5 Among the most often cited in the literature are: nutrient content,6 dietary variety score,7 the Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS),8 the Diet Quality Index (DQI),4 the Healthy Eating Index (HEI),9 and the revised Diet Quality Index.10

The HEI was created in 1995 by the US Department of Agriculture, with the goal of building a global diet quality index that would incorporate the nutritional needs and dietary guidelines for US consumers in a single measure.11 The HEI consists of ten items, which are based on different aspects of a healthy diet, and was adapted to Brazil based on the Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population (DAPBs)12 by Domene et al.13 for use with preschool children aged two to six years.

This study evaluates the dietary quality of a sample of preschoolers in Pelotas, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, using the HEI.

MethodThis study uses data on the diet of preschoolers participating in a population-based cross-sectional study, which consisted as the fourth assessment of a time series aiming to assess the effect of iron fortification of wheat flour and corn meal on anemia in children aged14 Methodological data are described in a previous publication.14

The interview was carried out by trained nutritionists, with the child's mother or guardian, using a pre-coded questionnaire. Demographic variables were collected (gender and age of the children in months) as well as socio-economic (family income in minimum wages), maternal schooling (in years) and dietary variables. Food frequency questionnaire (FFQ), a quantitative tool with 56 food items distributed in cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, meat and meat products, fats, sugars and other foods, with a recall period of one year, was developed for the study, and used to assess food consumption and the dietary quality. The FFQ was validated using three 24-h recalls. The de-attenuated Pearson's correlation coefficients were all equal to or greater than 0.50 for macronutrients calcium, iron, sodium, vitamin C, cholesterol and saturated fat (unpublished data).

Dietary quality was analyzed using the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) proposed by Domene et al.13 Thus, a score was generated from the points obtained for the 13 components. The first eight were related to the food groups: (1) cereals; (2) vegetables; (3) fruits and fruit juices; (4) milk and dairy products; (5) meat and eggs; (6) legumes; (7) oils and fats, and (8) sugars, candies, chocolates and snacks. These eight components contribute with 50% of the total score. To adapt the HEI, which originally classifies the food into five dietary groups, a proportional reduction in the sum of the possible number of points was performed from 80 to 50. The other five components, which contributed the remaining 50% of the score, were: (9) total fat; (10) saturated fat; (11) cholesterol; (12) sodium, and (13) diet variety.

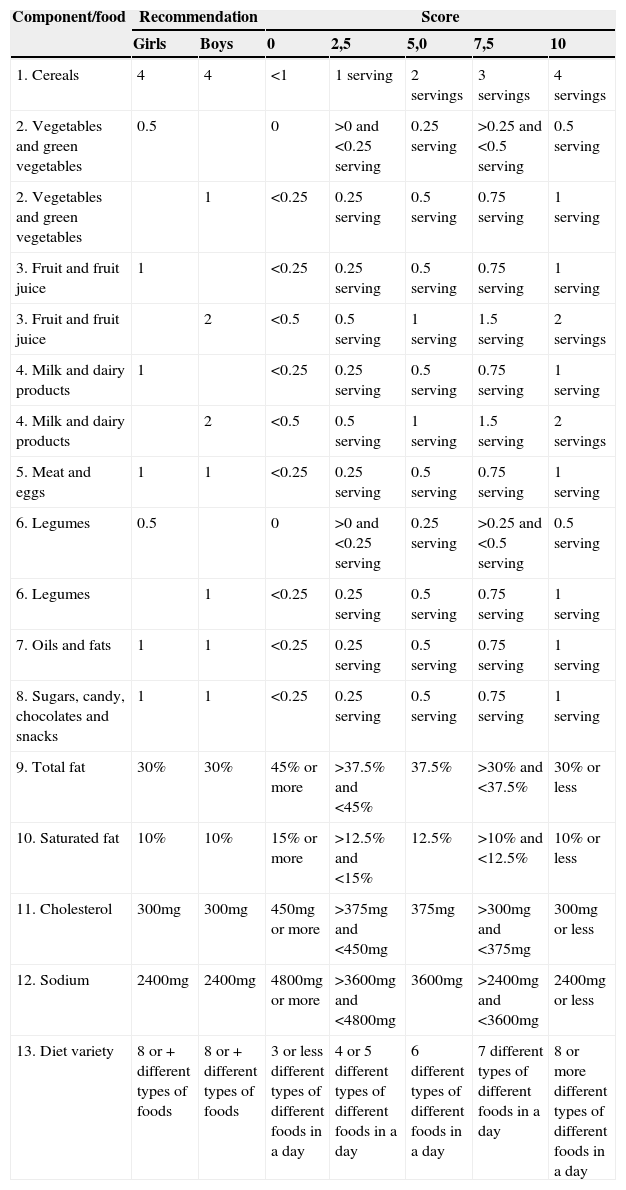

To score components 1–8, the ideal number of servings to be consumed daily was determined by the ratio between the energy requirements of the age range and the number of servings suggested by the Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population (DAPBs),12 which have been adapted according to the age and the recommendations of the Brazilian Society of Pediatrics (SBP).15 Each food consumed received a score according to the size of the consumed serving, as shown in Table 1. In this chart, some components are repeated, as some recommendations are different for boys and girls.

Criteria for the Healthy Eating Index (HEI) score in preschool children according to components 1–13.

| Component/food | Recommendation | Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Girls | Boys | 0 | 2,5 | 5,0 | 7,5 | 10 | |

| 1. Cereals | 4 | 4 | <1 | 1 serving | 2 servings | 3 servings | 4 servings |

| 2. Vegetables and green vegetables | 0.5 | 0 | >0 and <0.25 serving | 0.25 serving | >0.25 and <0.5 serving | 0.5 serving | |

| 2. Vegetables and green vegetables | 1 | <0.25 | 0.25 serving | 0.5 serving | 0.75 serving | 1 serving | |

| 3. Fruit and fruit juice | 1 | <0.25 | 0.25 serving | 0.5 serving | 0.75 serving | 1 serving | |

| 3. Fruit and fruit juice | 2 | <0.5 | 0.5 serving | 1 serving | 1.5 serving | 2 servings | |

| 4. Milk and dairy products | 1 | <0.25 | 0.25 serving | 0.5 serving | 0.75 serving | 1 serving | |

| 4. Milk and dairy products | 2 | <0.5 | 0.5 serving | 1 serving | 1.5 serving | 2 servings | |

| 5. Meat and eggs | 1 | 1 | <0.25 | 0.25 serving | 0.5 serving | 0.75 serving | 1 serving |

| 6. Legumes | 0.5 | 0 | >0 and <0.25 serving | 0.25 serving | >0.25 and <0.5 serving | 0.5 serving | |

| 6. Legumes | 1 | <0.25 | 0.25 serving | 0.5 serving | 0.75 serving | 1 serving | |

| 7. Oils and fats | 1 | 1 | <0.25 | 0.25 serving | 0.5 serving | 0.75 serving | 1 serving |

| 8. Sugars, candy, chocolates and snacks | 1 | 1 | <0.25 | 0.25 serving | 0.5 serving | 0.75 serving | 1 serving |

| 9. Total fat | 30% | 30% | 45% or more | >37.5% and <45% | 37.5% | >30% and <37.5% | 30% or less |

| 10. Saturated fat | 10% | 10% | 15% or more | >12.5% and <15% | 12.5% | >10% and <12.5% | 10% or less |

| 11. Cholesterol | 300mg | 300mg | 450mg or more | >375mg and <450mg | 375mg | >300mg and <375mg | 300mg or less |

| 12. Sodium | 2400mg | 2400mg | 4800mg or more | >3600mg and <4800mg | 3600mg | >2400mg and <3600mg | 2400mg or less |

| 13. Diet variety | 8 or+different types of foods | 8 or+different types of foods | 3 or less different types of different foods in a day | 4 or 5 different types of different foods in a day | 6 different types of different foods in a day | 7 different types of different foods in a day | 8 or more different types of different foods in a day |

The score of components 9–13 required no adjustments and was carried out using the same parameters indicated by Bowman et al.9 For the intake of total fat and saturated fat, the score criterion used was the percentage of daily energy provided by these nutrients. The maximum score (10) was attributed to values ≤30% for total and 10% for saturated fat, while for the minimum score criterion (zero), the values of 45% and 15% were used for total and saturated fat, respectively. For cholesterol and sodium intake, the maximum score of 10 was attributed to those who consumed 300mg or less of cholesterol and 2400mg or less of sodium per day. The minimum score of zero was given to those who consumed 450mg or more of cholesterol and 4800mg or more of sodium per day. Finally, for the scoring of diet variety, only foods from the first six groups were considered, excluding food classified as oil and fats or as candy and snacks. The maximum score of 10 was obtained when the child had consumed at least a half serving of eight or more different types of food in a day. A minimum score of zero was attributed when the child had consumed three or less types of food in a day. Intermediate values were attributed to all evaluated components, as shown in Table 1.

HEI final score was attained by adding the 13 assessed components, with 50% of the score being obtained from components 1–8, and the other half from components 9–13. When scoring, the following intervals were considered: values ≥80 points characterized the diet as adequate; between 51 and 80 points, as needing improvement, and a score <51 characterized a poor diet.9

Demographic, socioeconomic and frequency of food intake data were processed through double entry with consistency checking of information using Epi Info 6.0 software program. Foods and food preparations recorded in the food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) were analyzed for their nutritional composition using the HHHQ program – DietSys Analysis Software, release 4.02, National Cancer Institute, 1999. This information was analyzed using Stata software program, release 11.1. Descriptive analyses were performed to characterize the sample. Student's t test was used to compare HEI means by gender. Finally, we carried out bivariate analyses between exposures and HEI means by simple linear regression.

All analyses considered a value of p<0.05 for statistical significance. Sample variation was shown as standard error, as the analysis took into account the sampling design (svy command in Stata software program, release 11.1.), considering that the sampling process was carried out in multiple stages.14 The standard error of the mean is obtained by dividing the sample standard deviation by the square root of the number of observations, and it indicates, similar to the standard deviation, the inaccuracy associated with the estimation of means.

The children's parents or guardians gave their written consent before the collection of information. This study was submitted to the Institutional Review Board of the Universidade Federal de Pelotas, and was approved under submission number 011/08.

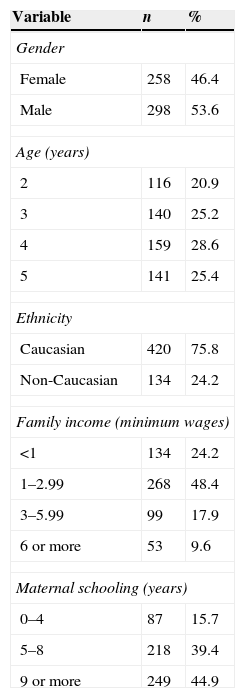

ResultsThe original study assessed 799 children aged zero to five years. These accounted for 94% of the initially calculated sample, which yielded a low percentage of losses and refusals.14 After excluding 243 children younger than two years old, the diet of 556 children aged 2–5 years was evaluated. The mean age was four years (SE=0.5); most of them were males (53.6%), Caucasians (75.8%), whose mothers had nine or more years of schooling (44.9%), and whose families had a monthly income between one and <3 minimum wages (48.4%), as shown in Table 2.

Description of the sample of preschool children by gender, age, ethnicity, family income and maternal education.

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 258 | 46.4 |

| Male | 298 | 53.6 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 2 | 116 | 20.9 |

| 3 | 140 | 25.2 |

| 4 | 159 | 28.6 |

| 5 | 141 | 25.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 420 | 75.8 |

| Non-Caucasian | 134 | 24.2 |

| Family income (minimum wages) | ||

| <1 | 134 | 24.2 |

| 1–2.99 | 268 | 48.4 |

| 3–5.99 | 99 | 17.9 |

| 6 or more | 53 | 9.6 |

| Maternal schooling (years) | ||

| 0–4 | 87 | 15.7 |

| 5–8 | 218 | 39.4 |

| 9 or more | 249 | 44.9 |

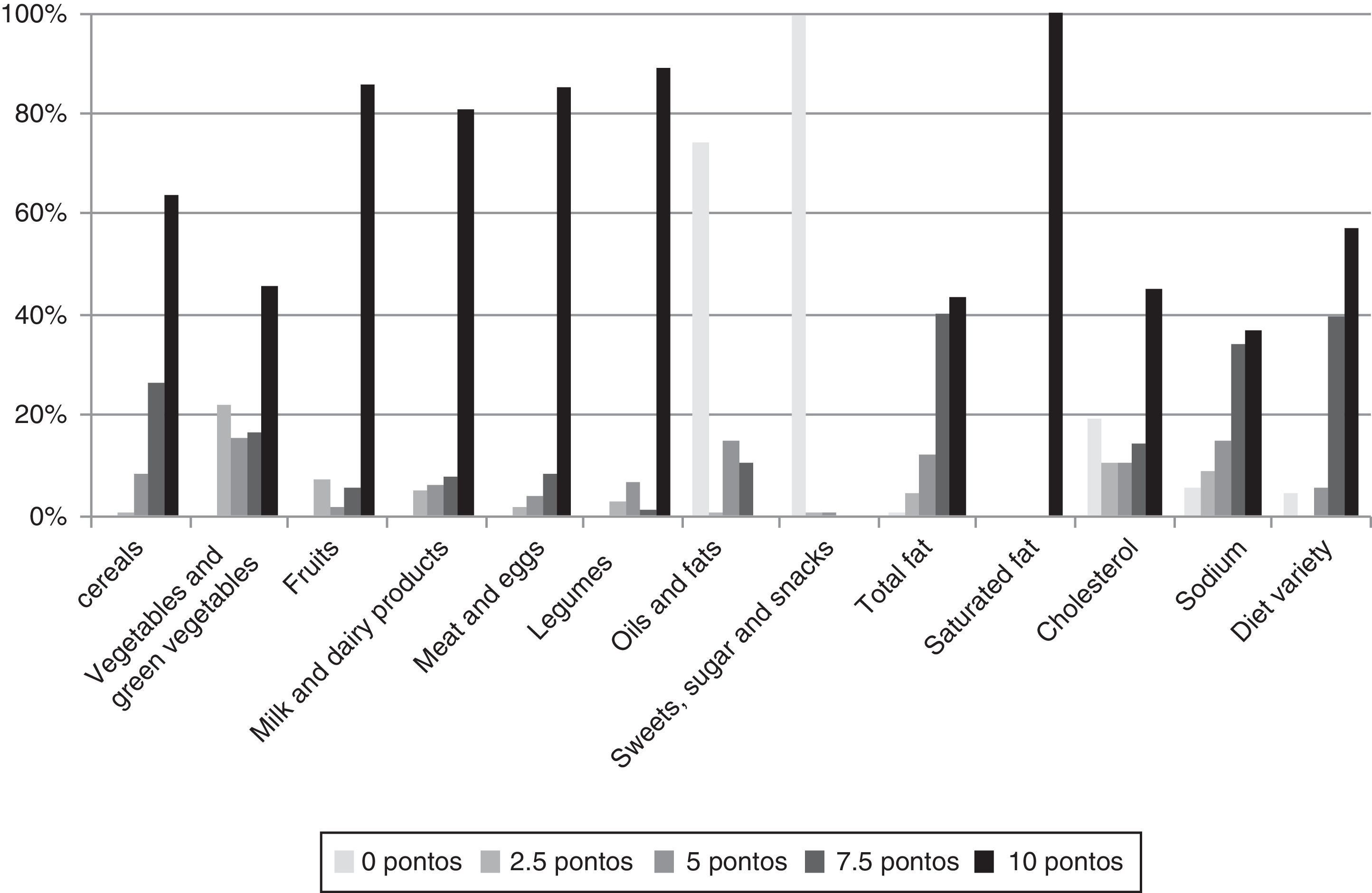

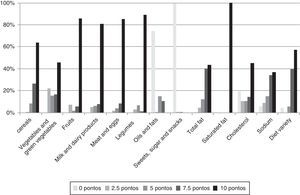

Foods less often consumed by the preschoolers were vegetables/green vegetables and cereals, with respectively 45.7% and 64.0% of children having consumed the recommended daily amount. The most often consumed were those belonging to the group of sweets, sugars and snacks, being consumed by 99.6% of children. Foods from the group of oils and fats had a higher consumption than that recommended by 74.3% of children. Foods from the group of meat and eggs, legumes, fruits, milk and dairy products showed an adequate intake, ranging between 81.1% and 89.2% (Fig. 1).

A high score was observed in the evaluation regarding components 9–12 (total fat, saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium), with 100% of children reaching the score of 10 in saturated fat consumption. Regarding the diet variety component, 57.4% of the children consumed eight or more different types of foods in one day (Fig. 1).

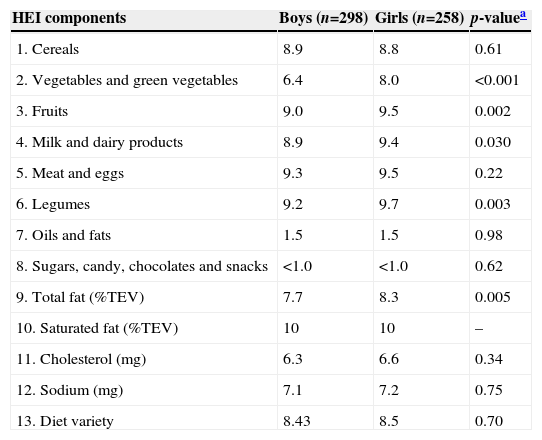

Table 3 shows the mean score for each of the 13 components of the HEI according to the children's gender. Of the 10 attainable points in each of the components, we observed that girls achieved higher scores than boys for the consumption of vegetables and green vegetables (8.0 vs. 6.4), fruits (9.5 vs. 9.0), milk and dairy products (9.4 vs. 8.9), legumes (9.7 vs. 9.2), and total fat (8.3 vs. 7.7).

Mean HEI score for each component according to preschoolers’ gender.

| HEI components | Boys (n=298) | Girls (n=258) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cereals | 8.9 | 8.8 | 0.61 |

| 2. Vegetables and green vegetables | 6.4 | 8.0 | <0.001 |

| 3. Fruits | 9.0 | 9.5 | 0.002 |

| 4. Milk and dairy products | 8.9 | 9.4 | 0.030 |

| 5. Meat and eggs | 9.3 | 9.5 | 0.22 |

| 6. Legumes | 9.2 | 9.7 | 0.003 |

| 7. Oils and fats | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.98 |

| 8. Sugars, candy, chocolates and snacks | <1.0 | <1.0 | 0.62 |

| 9. Total fat (%TEV) | 7.7 | 8.3 | 0.005 |

| 10. Saturated fat (%TEV) | 10 | 10 | – |

| 11. Cholesterol (mg) | 6.3 | 6.6 | 0.34 |

| 12. Sodium (mg) | 7.1 | 7.2 | 0.75 |

| 13. Diet variety | 8.43 | 8.5 | 0.70 |

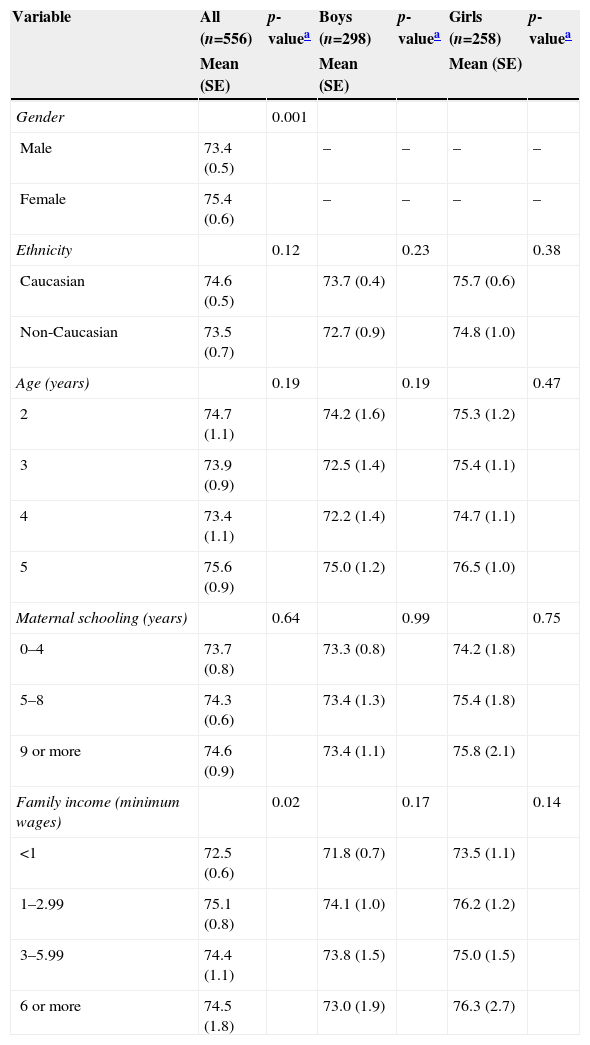

Of the maximum 100 attainable points in the HEI score, the mean score achieved by the assessed children was 74.4 points (SE=0.4), being higher among girls than among boys (75.4; SE=0.6 vs. 73.4; SE=0.5, respectively). Regarding family income, children from families with income between 1 and 2.99 minimum wages had a higher mean score (75.1, SE=0.8) compared to those whose family income was higher or lower than 1 minimum wage. Ethnicity, age and maternal schooling showed no statistically significant association with the mean scores, as shown in Table 4.

Mean HEI score based on the variables of interest for all preschoolers stratified by gender.

| Variable | All (n=556) | p-valuea | Boys (n=298) | p-valuea | Girls (n=258) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | ||||

| Gender | 0.001 | |||||

| Male | 73.4 (0.5) | – | – | – | – | |

| Female | 75.4 (0.6) | – | – | – | – | |

| Ethnicity | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.38 | |||

| Caucasian | 74.6 (0.5) | 73.7 (0.4) | 75.7 (0.6) | |||

| Non-Caucasian | 73.5 (0.7) | 72.7 (0.9) | 74.8 (1.0) | |||

| Age (years) | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.47 | |||

| 2 | 74.7 (1.1) | 74.2 (1.6) | 75.3 (1.2) | |||

| 3 | 73.9 (0.9) | 72.5 (1.4) | 75.4 (1.1) | |||

| 4 | 73.4 (1.1) | 72.2 (1.4) | 74.7 (1.1) | |||

| 5 | 75.6 (0.9) | 75.0 (1.2) | 76.5 (1.0) | |||

| Maternal schooling (years) | 0.64 | 0.99 | 0.75 | |||

| 0–4 | 73.7 (0.8) | 73.3 (0.8) | 74.2 (1.8) | |||

| 5–8 | 74.3 (0.6) | 73.4 (1.3) | 75.4 (1.8) | |||

| 9 or more | 74.6 (0.9) | 73.4 (1.1) | 75.8 (2.1) | |||

| Family income (minimum wages) | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.14 | |||

| <1 | 72.5 (0.6) | 71.8 (0.7) | 73.5 (1.1) | |||

| 1–2.99 | 75.1 (0.8) | 74.1 (1.0) | 76.2 (1.2) | |||

| 3–5.99 | 74.4 (1.1) | 73.8 (1.5) | 75.0 (1.5) | |||

| 6 or more | 74.5 (1.8) | 73.0 (1.9) | 76.3 (2.7) |

HEI, Healthy Eating Index; SE, standard error.

This population-based study, carried out in a medium-sized city of southern Brazil, showed that the children's diet needs improvement. A similar result was found by Domene et al.13 in a study that assessed the diet of 94 preschoolers aged 2–6 years living in poverty-stricken areas in the city of Campinas, where 70% of children had their diets classified between 51 and 80 points.

Approximately two-thirds of the children (64%) achieved the maximum score in the group of cereals, eating four servings a day. Barbosa et al.16 in a study with children aged 2–3 years attending a nonprofit day care center in the island of Paquetá, state of Rio de Janeiro, found that only 20% of them consumed cereals adequately.

Regarding the consumption of vegetables and green vegetables, only 45.7% of the children consumed the recommended servings established in the HEI, which are two servings for boys and one serving for girls. The opposite was observed for adequate fruit consumption (2 servings a day for boys and one for girls), as 86% of the children consumed the recommended servings. Fruits, vegetables and green vegetables are sources of dietary fiber, with a positive impact on body weight, blood glucose levels and concentrations of blood lipids, in addition to increasing the fecal bolus, preventing intestinal constipation,17 and being excellent sources of vitamins and minerals.18

A considerable consumption of milk and dairy products was observed, as 81.1% of children reached the recommendation for this group, which are 2 daily servings for boys and one for girls. This finding corroborates the study carried out by Valente et al.19 with 39 preschool children from a day care center in Santa Maria, state of Rio Grande do Sul, in which the authors found that 92.3% of the children consumed milk one or more times a day. Milk is very often present in the diet of the assessed children's age range and a great source of calcium. However, it is necessary to consider the fact that many children substitute important meals, such as breakfast and lunch, for a bottle of milk.3,17

Regarding the consumption of meat and eggs, 85.4% of the children consumed the recommended amount (1 daily serving). In the study performed by Castro et al.20 half of the preschool children (53.8%) consumed meats once to three times a week. Meats, especially red meat, are rich in iron, a component of enzymes that participate in the process of cellular respiration and are essential for the transport of oxygen and carbon dioxide in blood. Its deficiency can lead to anemia, with consequent growth and cognitive development impairment.20,21

As for legumes, a group evaluated through the consumption of beans, they are important sources of iron, folic acid and dietary fibers, and were present in the daily diet of 89.2% of children, who reached the highest score in this food group.

The consumption of sugar, candies, chocolates and snacks was above the recommended amount, as 99.6% of the children daily consumed more than 1 serving of foods from this group. Valente et al.19 in the study carried out in Santa Maria, observed that over half of the children consumed chocolate milk one or more times a day. This product usually contains more than 70% of sucrose in its composition; sucrose being the most cariogenic carbohydrate, as it is a great substrate for pathogenic oral microorganisms.3 In a study carried out by Barbosa et al.22 sugar consumption was three times higher than the recommended amount (1 serving), mainly due to the high consumption of artificial fruit juices, soft drinks, candy and added sugar.

All children in this study consumed servings from the group of oils and fats above the recommended amount, which is one daily serving. This may contribute to the development of Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases (CNDs). Of the children, 43% achieved the recommendation for total fat component, that is, an intake lower than 30% of the daily total energy value (TEV) derived from this nutrient. In relation to saturated fat, 100% of the children had intakes that represented 10% or less of caloric intake of this nutrient in the TEV. The adequate consumption of this type of fat reduces the risk of heart disease and dyslipidemia. Fats are sources of essential fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K), which must necessarily be supplied by food, as the body cannot produce them. Thus, all human beings need food sources of fat. It is important to differentiate the healthier ones, which are essential for adequate body functions, from those to be avoided as they damage health, in addition to consuming them within the recommended ranges for good nutrition.12

As for the sodium and cholesterol components, 36.9% and 45.1% of the children, respectively, attained the highest score, ingesting ≤2400mg of sodium daily and ≤300mg of cholesterol daily. Frequent and high consumption of fats and salt increases the risk of diseases such as obesity, hypertension and heart disease. Cholesterol is a component of cell walls and precursor of many hormones (estrogen and testosterone) and bile acids, and it also participates in the fat absorption and vitamin D synthesis processes; however, its excessive consumption carries health risks.12

As for the diet variety, the results indicated a varied diet, as 97.3% of the children attained more than 7 points in this component, as they consumed seven or more types of food daily. This finding corroborates the study carried out by Domene et al.13 in which 81% of the children obtained more than 6 points, characterizing a varied diet.

The mean HEI score was higher in girls than in boys (75.4 and 73.4, respectively), in contrast to the study by Domene et al.13 Children from families with income between 1 and <3 minimum wages achieved higher scores when compared to those whose income was lower or greater than that category. This may be related to the fact that poorer families have little access to foods such as fruits, vegetables, meat and milk, whereas children from higher income families consume more processed foods. In this sense, in addition to the family, the school's role becomes important, as it instructs on the importance of the nutrient intake and offers, in a balanced way, the foods that provide these nutrients.23

There are advantages in applying the HEI to the Brazilian population, as it is based on the consumption of food groups and not only of nutrients. The HEI allows the measurement of the complexity of different eating patterns as scored items and the analysis consumption trends, if applied repeatedly.24 Moreover, because the score was adapted to the assessed age group, the results adequately reflect the quality of the diet assessed.

The study assessed diet quality using a FFQ tool built especially for this research, and therefore suited to local reality. The main limitation of the use of this index is that excessive consumption of certain food groups is not scored separately, thus not making it possible to differentiate beneficial or harmful excessive consumption.

This study showed that, according with the HEI, the children's consumption of vegetables and green vegetables was below the recommended level, whereas foods from the group of oils and fats, as well as from the group of sugars, candies, chocolates and snacks were consumed in excess. These foods are calorically dense and nutrient-poor, being part of poor eating habits. In this sense, to know about the child's diet quality and then reinforcing guidelines on healthy eating might be a way to improve the diet of children and promote healthier eating habits, which may persist in later life.

FundingThis study was funded by the Ministry of Health, Brazil.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.