Suicide is a global health issue and has been the primary cause of unnatural death in Spain since 2008.1 A history of previous suicide attempt is the strongest predictor of future suicidal behaviour.2 Within multiple suicide attempters, Kreitman and Casey were the first authors to mention the concept of “major repeaters.3 In their seminal study published in 1988, they studied over 3000 parasuicide individuals and arbitrarily divided them into “first evers” (no previous suicide attempts), “minor repeaters” (individuals with 2–4 lifetime suicide attempts), and “major or grand repeaters” (individuals with ≥5 lifetime suicide attempts). Major repeaters represent approximately 10% of all suicide attempters,4 are heavy consumers of health resources, pose a challenge to clinicians, and are at higher risk of suicide.3,5 Major repeaters probably are a distinct phenotype displaying a more severe psychopathological profile and sharing some features with patients presenting addictions.6 Recently, we reported that emptiness appears to be a core characteristic of at least a group of major repeaters.7,8 The current letter is aimed at presenting further evidence describing the characteristics of major repeaters in a retrospective study.

This study included all suicide attempters (n=711) assessed at the emergency room or medical inpatient units at Lleida Hospital (Spain) by liaison psychiatrists between 2009 and 2014. The Lleida Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study. All participants were evaluated by semi-structured interviews using an ad hoc protocol including sociodemographic and clinical data. We conducted univariate analyses to explore whether sociodemographic and clinical variables were associated with major repeater status. Cross-tabulations compared the dichotomous dependent variable major repeaters (yes/no) with other independent dichotomous variables. The Fisher Exact Test (FET) provided significance and odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) provided the effect size (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Significant variables (p<0.05) in univariate analyses were introduced in bivariate logistic regression models.

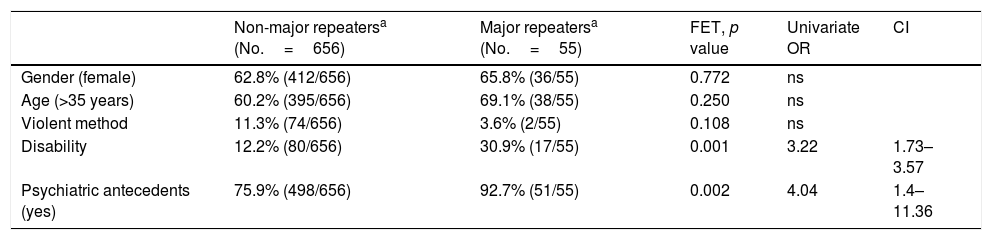

The mean (SD) age of suicide attempters was 39.8 years (15.3) and 63% (448/711) were women. Table 1 displays the most relevant results in univariate analyses. Similarly to prior studies (range 7–13%), major repeaters were 8% of all suicide attempters4,6,9 but, in contrast, we found no statistically significant increase of females in major repeaters. Importantly, 72.7% (40/55) of major repeaters, compared to 55.6% (365/656) (FET p=0.016) of the remaining suicide attempters, were unemployed (including jobless, retired, or disabled) providing an OR=1.13–3.57. But the most important finding of the present study are that major repeaters were more likely than the remaining suicide attempters: 1) to have previous psychiatric diagnoses; and 2) to be disabled. Further statistical proof of the relevance of disability was established by the logistic regression, as both risk factors remained independent. This novel finding is in keeping with previous literature relating disability with suicidal behaviour.10 Our study extends previous findings by suggesting that disability increases the risk for major suicide attempt repetition, and that this effect is not secondary to psychiatric diagnoses.

Univariate and backward stepwise logistic regression model for major repeaters.

| Non-major repeatersa (No.=656) | Major repeatersa (No.=55) | FET, p value | Univariate OR | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 62.8% (412/656) | 65.8% (36/55) | 0.772 | ns | |

| Age (>35 years) | 60.2% (395/656) | 69.1% (38/55) | 0.250 | ns | |

| Violent method | 11.3% (74/656) | 3.6% (2/55) | 0.108 | ns | |

| Disability | 12.2% (80/656) | 30.9% (17/55) | 0.001 | 3.22 | 1.73–3.57 |

| Psychiatric antecedents (yes) | 75.9% (498/656) | 92.7% (51/55) | 0.002 | 4.04 | 1.4–11.36 |

| Backward stepwise logistic regression modelb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Wald χ2c | p values | Corrected OR | CI | |

| First step | Previous psychiatric diagnoses | 5.10 | 0.024 | 3.33 | 1.17–9.49 |

| Disability | 9.70 | 0.002 | 2.70 | 1.44–5.08 | |

FET=Fisher's exact test; CI: 95% confidence interval; df: degrees of freedom; ns: non-significant; OR: odds ratio.

The current study has some limitations. As in all retrospective studies, the present study provided statistical associations that cannot be interpreted as causal. However, retrospective analyses can be useful to establish which may be the characteristics of major repeaters that consistently replicate across samples and explore whether there are subgroups within major attempters, in order to plan large prospective studies.

In conclusion, this current sample suggests that major repeaters may be characterized by disability and elevated psychopathological burden.

Disclosure statementsThis article received no support from any funding agency, commercial business, or not-for-profit institution. In the last three years, Dr. Blasco-Fontecilla has received lecture fees from Eli Lilly, AB-Biotics, Janssen, and Shire. The remaining authors declare no commercial conflicts of interest in the last 3 years.

The authors thank Lorraine Maw, M.A., for editorial assistance.

Please cite this article as: Irigoyen-Otiñano M, Puigdevall-Ruestes M, Prades-Salvador N, Salort-Seguí S, Gayubo L, de Leon J, et al. Más evidencias de que los grandes repetidores se comportan como un subgrupo en la conducta suicida. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2018;11:60–61.