We investigated the presence of cognitive biases in people with a recent-onset psychosis (ROP), schizophrenia and healthy adolescents and explored potential associations between these biases and psychopathology.

MethodsThree groups were studied: schizophrenia (N = 63), ROP (N = 43) and healthy adolescents (N = 45). Cognitive biases were assessed with the Cognitive Biases Questionnaire for Psychosis (CBQ). Positive, negative and depressive symptoms were assessed with the PANSS and Calgary Depression Scale (ROP; schizophrenia) and with the CAPE-42 (healthy adolescents). Cannabis use was registered. The association between CBQ and psychopathology scales was tested with multiple linear regression analyses.

ResultsPeople with schizophrenia reported more cognitive biases (46.1 ± 9.0) than ROP (40 ± 5.9), without statistically significant differences when compared to healthy adolescents (43.7 ± 7.3). Cognitive biases were significantly associated with positive symptoms in both healthy adolescents (Standardized β = 0.365, p = 0.018) and people with psychotic disorders (β = 0.258, p = 0.011). Cognitive biases were significantly associated with depressive symptoms in healthy adolescents (β = 0.359, p = 0.019) but in patients with psychotic disorders a significant interaction between schizophrenia diagnosis and CBQ was found (β = 1.804, p = 0.011), which suggests that the pattern differs between ROP and schizophrenia groups (positive association only found in the schizophrenia group). Concerning CBQ domains, jumping to conclusions was associated with positive and depressive symptoms in people with schizophrenia and with cannabis use in ROP individuals. Dichotomous thinking was associated with positive and depressive symptoms in all groups.

ConclusionsCognitive biases contribute to the expression of positive and depressive symptoms in both people with psychotic disorders and healthy individuals.

Investigamos la presencia de sesgos cognitivos en personas con psicosis de reciente comienzo (ROP), esquizofrenia y adolescentes sanos, y exploramos las asociaciones potenciales entre estos sesgos y la psicopatología.

MétodosSe estudiaron tres grupos: esquizofrenia (N = 63), ROP (N = 43) y adolescentes sanos (N = 45). Los sesgos cognitivos se evaluaron utilizando Cognitive Biases Questionnaire for Psychosis (CBQ). Los síntomas positivos, negativos y depresivos se evaluaron utilizando las escalas PANSS and Calgary Depression Scale (ROP; esquizofrenia) y CAPE-42 (adolescentes sanos). Se registró el consumo de cannabis. La asociación entre CBQ y las escalas de psicopatología se probó utilizando un análisis de regresión lineal múltiple.

ResultadosLas personas esquizofrénicas reportaron más sesgos cognitivos (46,1 ± 9) que las personas con ROP (40 ± 5,9), sin diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la comparación con los adolescentes sanos (43,7 ± 7,3). Los sesgos cognitivos se asociaron significativamente a los síntomas positivos, tanto en adolescentes sanos (β = 0,365 estandarizada; p = 0,018) como en personas con trastornos psicóticos (β = 0,258; p = 0,011). Los sesgos cognitivos se asociaron significativamente a síntomas depresivos en adolescentes sanos (β = 0,359; p = 0,019), pero en pacientes con trastornos psicóticos se encontró una interacción significativa entre diagnóstico de esquizofrenia y CBQ (β = 1,804; p = 0,011), lo cual sugiere que el patrón difiere entre los grupos de ROP y esquizofrenia (solo se encontró asociación positiva en el grupo de esquizofrenia). En cuanto a los dominios de CBQ, el adoptar conclusiones se asoció a síntomas positivos y depresivos en las personas esquizofrénicas y que consumen cannabis en los individuos con ROP. El pensamiento dicótomo se asoció a síntomas positivos y depresivos en todos los grupos.

ConclusionesLos sesgos cognitivos contribuyen a la expresión de síntomas positivos y depresivos, tanto en las personas con trastornos psicóticos como en los individuos sanos.

The cognitive model of psychosis suggests that psychotic symptoms arise as a consequence of biased information processing.1,2 According to this model, people diagnosed with schizophrenia tend to present different cognitive biases that play a central role in evaluation, reasoning and metacognition processes,3,4 possibly resulting in the formation and maintenance of delusions.5

A consistent body of research has shown that delusional ideations are related to attributional biases (the tendency to attribute events to external or internal sources).6 During tasks of hypothetical situations, individuals with paranoid delusions show a tendency to form internal attributions to positive events while forming external attributions to negative ones, which is known as the self-serving bias.7 Some studies indicate that people with delusions tend to form personal and external attributions of negative situations more than those without delusions.4,8 Other studies show that in people with schizophrenia, the attributional biases do not shape delusional content but contribute to the self-blame for negative events.9

Another bias that has been found in people with delusions is the bias against disconfirmatory evidence10 (the tendency to disregard evidence that is contradictory to the hypothesis), an exaggerated tendency to pay attention to interpersonal threat11 (excessive perception of others’ behaviour as threatening), and, especially, jumping to conclusions (JTC)12 (deciding without sufficient evidence). Studies show that JTC is present in approximately 40%–70% of people with delusions3,5 and is associated with both delusional conviction and emotional distress.13 A recent meta-analysis concluded that JTC bias is associated with delusions specifically, rather than merely with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or with mental health difficulties.12

Research on cognitive biases in people with recent-onset psychosis (ROP) has shown that JTC is a common bias in many people in first-episode services and may relate to delusions.14 The presence of attributional bias in ROP is controversial, as some studies have reported that both self-serving and personalization biases are associated with delusional ideation in people with ROP,15 whereas other studies have not found this association.16,17

Psychotic symptoms may be framed in a dimensional theoretical model, a continuum, where an extended psychosis phenotype stretches from the psychopathological diluting into the normative.18 This model approaches the psychotic phenotype as a transdiagnostic feature by including the study of psychotic symptoms in people with psychotic disorders and psychotic-like experiences in healthy individuals. Although it might be argued that psychotic-like experiences in healthy individuals and psychotic symptoms in people with a psychotic disorder are different phenomena, previous research suggests that psychotic-like experiences could be seen as an “intermediate” phenotype, qualitatively similar to the psychotic phenotype but quantitatively less severe.19 As psychotic-like experiences might appear in adolescents and are a risk factor of developing a psychotic disorder,20 it is important to conduct studies in non-clinical populations of adolescents to explore the potential relationship between cognitive biases and psychotic-like experiences. Moreover, cognitive biases show convergent validity with subthreshold psychotic experiences in adolescents and young adults.21

A recent study including an adult sample reported an association between JTC reasoning bias and psychotic-like experiences in healthy controls.17 Other recent studies22 in non-clinical populations have also suggested that cannabis use is associated with cognitive biases that contribute to the risk of reporting psychotic-like experiences. In that study, both cannabis use and cognitive biases mediated the relationship between childhood trauma and psychotic-like experiences. Cannabis use is associated with the risk of developing a psychotic disorder23 and a poorer prognosis24 in people with a psychotic disorder. Therefore, it is also important to control for cannabis use in the potential relationship between cognitive biases and symptoms.

The main aim of our study was to explore the association between cognitive biases and symptoms in three samples of participants: (1) a non-clinical group of healthy adolescents, (2) a group of young adults with a ROP, and (3) people with a chronic psychotic disorder. We hypothesized that cognitive biases would be more severe in people with schizophrenia when compared to ROP and healthy adolescents. We also hypothesized that the severity of cognitive biases would be associated with psychopathological symptoms, particularly positive and depressive symptoms (people with ROP or schizophrenia) or positive and depressive psychic experiences (adolescents).

MethodsSampleWe designed a cross-sectional, case-control study that included three groups of individuals: (1) people with schizophrenia (N = 63), (2) people with ROP (N = 43), and (3) healthy adolescents (N = 45). All participants were recruited by consecutive sampling.

People with schizophrenia and ROP were attending the Department of Mental Health from Parc Taulí Hospital (Sabadell, Spain) at two different units: Community Rehabilitation Service (people with schizophrenia) and Early Intervention Service (people with ROP). People with a psychotic disorder had stable antipsychotic treatment during the previous month. All participants from the schizophrenia group met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and had a duration of illness >3 years. People in the ROP group met any of the following DSM-IV-TR diagnoses: schizophreniform disorder (N = 15), schizophrenia (N = 3), schizoaffective disorder (N = 2), brief psychotic episode (N = 1), or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified (N = 22) with a duration of illness <3 years. The exclusion criteria for people with a psychotic disorder were severe neurological disease or intellectual disability, severe head injury or neurological disease and active substance dependence (other than tobacco or cannabis).

The group of healthy adolescents was recruited among healthy students from a high school in the province of Barcelona that anonymously completed self-applied questionnaires. Sociodemographic and clinical variables were recollected. Subjects reporting a diagnosis of psychiatric or neurological conditions were excluded from the study.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Parc Taulí Hospital. The study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI15/01386 and PI18/01843). All participants received an explanation of the study procedures and signed a written informed consent form to undergo clinical interviews and allow the use of data from their clinical history. The group of healthy adolescents gave oral consent to participate in the study before completing self-report questionnaires anonymously.

Clinical assessmentClinical diagnosis of psychotic disordersOPCRIT checklist v.4.0 (available at http://sgdp.iop.kcl.ac.uk/opcrit/) was used to generate DSM-IV diagnoses for psychotic disorders. This diagnostic system has shown good inter-rater reliability.25

Socio-demographics and substance useSocio-demographic data and substance use (cannabis, alcohol, and other substances) were assessed by semi-structured interviews in people with a psychotic disorder and by self-report questionnaires in healthy adolescents. Information regarding family history of mental disorders was not available for healthy adolescents.

Cognitive biasesThe Cognitive Biases Questionnaire for Psychosis (CBQ)26 was used to assess cognitive biases that are relevant to psychosis and was administered to all three groups. This self-report questionnaire includes five different subscales for cognitive biases: intentionalizing, catastrophizing, dichotomous thinking, JTC and emotional reasoning. Each item is rated on a three-point scale, where the highest score means higher intensity. The range for each cognitive bias subscale is between 5 and 18, and the total score ranges from 30 to 90 points.

Psychopathological symptomsPsychopathology in people with schizophrenia or ROP. Positive, negative and general psychopathology symptoms of schizophrenia were assessed with the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia (PANSS).27 We recoded all symptoms in five dimensions as recommended by a consensus: positive, negative, disorganized, excided and depressed.28

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS).29 The CDSS was specifically developed to distinguish depressive symptoms from positive and negative symptoms or antipsychotic-induced side effects in people with schizophrenia.30 Higher scores indicate a greater level of depression.

All heteroadministered psychometric scales were administered by the same clinical psychologist with expertise in psychotic disorders.

Psychopathology in healthy adolescentsPositive, negative and depressive experiences in healthy adolescents were assessed with the Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences–42 items (CAPE-42).31 This self-report questionnaire measures symptoms in three main domains: positive symptoms (20 items), negative symptoms (14 items), and depressive symptoms (8 items). We considered the symptom frequency of each item, which is rated at a 4-point Likert scale from 1 to 4. We calculated the weighted scores for each subscale as the sum of all items scores per dimension divided by the number of items filled in by the subject in that particular dimension.

Psychosocial functioning in people with schizophrenia or ROPSocial and personal functioning was assessed solely with the global score of the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP),32 which includes four domains of social and individual performance (socially useful activities, including work and education; personal and social relationships; self-care; disturbing and aggressive behaviour). The global score of functioning was computed from the results of all domains using a scale between 0 and 100.

Additional psychometric descriptions and analyses of the reliability and validity of the Spanish versions of the psychometric scales are described in Table S1 from Supplementary material.

Statistical analysisSPSS version 21.0 (IBM, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Baseline bivariate statistics were performed using ANOVA or chi-square tests, depending on the continuous or categorical nature of the variable. Spearman correlations were used to explore associations between ordinal or continuous data (e.g., CBQ scores and psychopathology).

To compare total CBQ scores between cannabis use and clinical diagnosis, an ANCOVA was used while adjusting by age. A MANCOVA was also performed to compare different CBQ dimensions between cannabis use and clinical diagnosis while adjusting by age. Significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed).

As an exploratory analysis, we compared healthy adolescents with or without psychotic-like experiences using the cut-off score for the CAPE-positive subscale (weighted score) >1.6. In previous studies that administered the CAPE-42 to people at ultra-high-risk (UHR) for psychosis,33 a cut-off of 3.2 that combined the frequency and distress CAPE-positive subscales had a positive predictive value of 72% and a negative predictive value of 68%. As we used the frequency subscale in our study, we considered the cut-off 1.6 for dividing the sample of healthy adolescents in two groups (low and high psychotic-like experiences).

Multiple linear regression analyses were used to explore the relationship between CBQ scores and psychopathology (PANSS dimensions and CDSS) or functionality (PSP). These multiple linear regressions were conducted in the sample of people with a psychotic disorder (including both ROP and schizophrenia groups). A separate multiple linear regression analysis was performed for each psychopathological variable, which was considered the dependent variable. In all models, the following independent variables were included: age, gender, cannabis use, schizophrenia diagnosis and CBQ total score. Potential interactions between CBQ and all independent variables were tested, and those statistically significant interactions were included in the final model. Dichotomous variables (e.g. cannabis use, schizophrenia diagnosis) were included in the multiple linear regression analyses as dummy variables (0 = No [reference category]; 1 = Yes).

There was no missing data for the CBQ or CAPE-42 tests. Three patients had incomplete data for the PANSS, which was handled with a listwise procedure in the multiple linear regression analyses. Multicollinearity was assessed with the variance inflating factor (VIF). All independent variables included in the model had a VIF < 5, suggesting that there were no problems of multicollinearity between predictors.

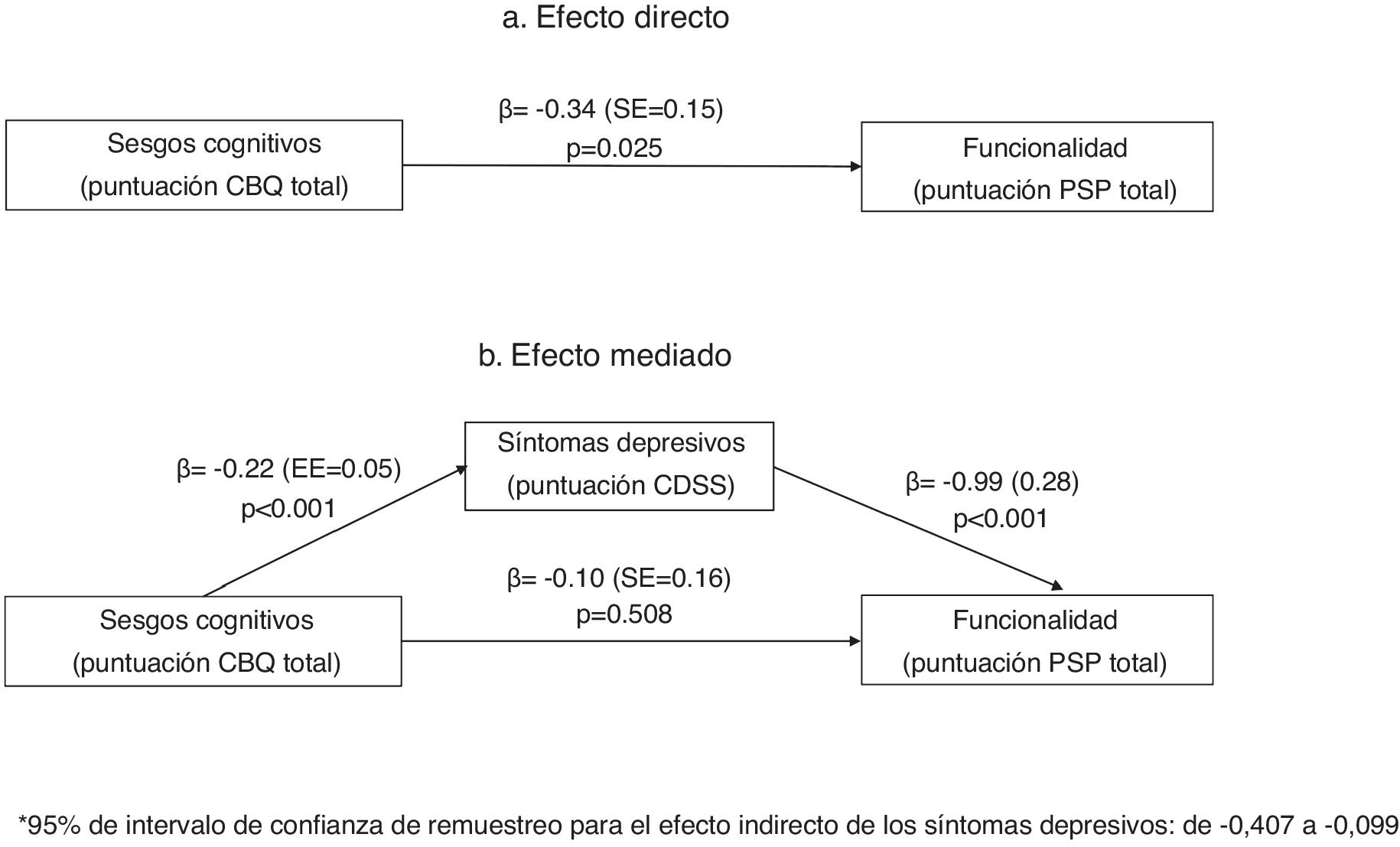

We conducted a mediation analysis according to Baron and Kenny34 and used bootstrapping to test the indirect effect of mediation.35 An SPSS macro36 was used. In the mediation analyses, we explored the potential mediating effect of psychopathological symptoms (positive, negative or depressive) in the relationship between cognitive biases (defined as the main independent variable) and functionality (defined as the outcome variable). These mediation analyses were also conducted in the sample of people with a psychotic disorder (ROP and schizophrenia). The significance of the indirect effects in this model was tested by bootstrapping. In brief, bootstrapping is a non-parametric method based on resampling with replacement that is performed many times. From each of these samples, the indirect (mediated) effect is computed, and a sampling distribution can be empirically generated. With the distribution, a confidence interval (CI) is determined and assessed to determine if zero is in the interval. If zero is not in the interval, then the researcher can be confident that the indirect effect is different from zero and that mediation exists (a more detailed explanation of the mediation analyses is included in Box S1 from Supplementary material).

The sample size was calculated with G Power version 3.1.9.4. With an α error of 0.05, β error of 0.2 (power = 80%), for detecting a moderate effect size (f2 = 0.2) with multiple linear regression and considering 6 covariates, the needed sample size was 42 (for each analysis).

Our main hypotheses were tested with multivariate analyses. We also included many exploratory univariate analyses that were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, as it is not strictly necessary to adjust for multiple comparisons in analyses that are exploratory.37

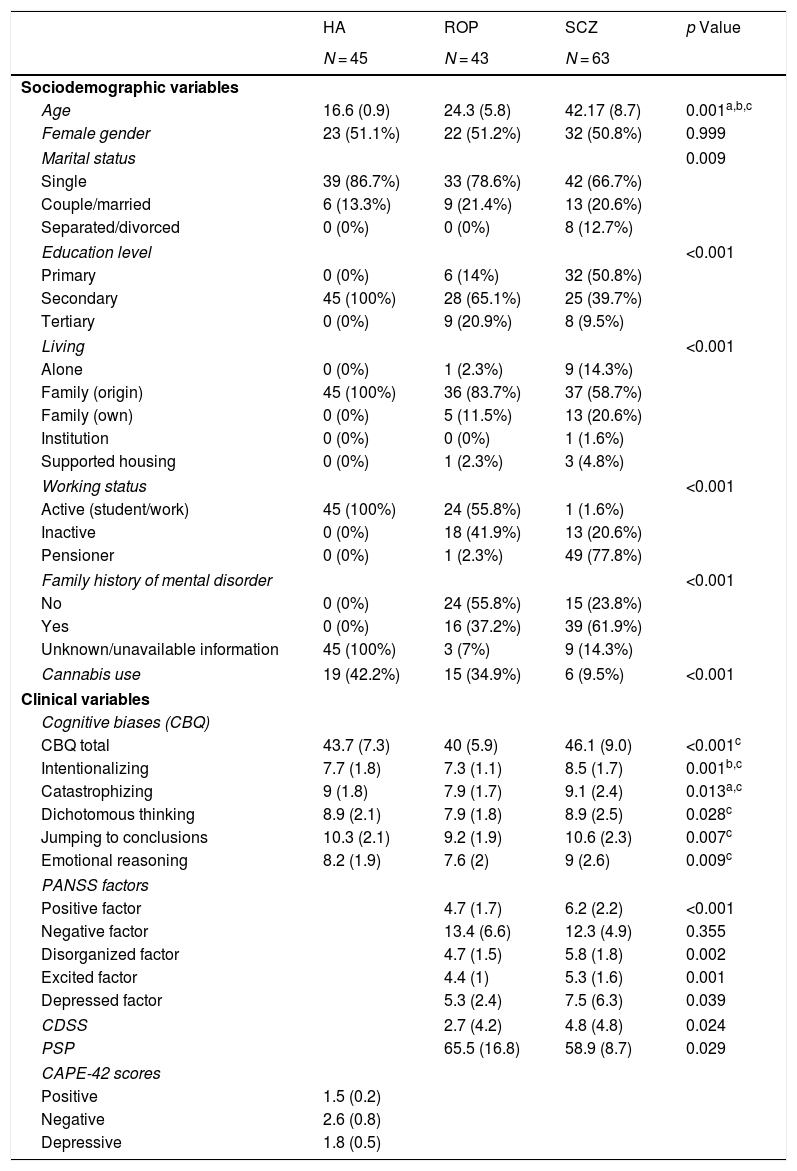

ResultsUnivariate analysesTable 1 shows the demographic characteristics and clinical variables of the sample. The 3 groups did not differ in gender. There were statistically significant differences in age, marital status, living, working status, educational level and family history of mental disorders. Cannabis use was greater in healthy adolescents and people with ROP than in those with schizophrenia. People with schizophrenia scored significantly higher in all cognitive biases than the ROP group. However, people with schizophrenia did not differ from healthy adolescents in cognitive biases, except for in the intentionality subscale, in which they scored higher than healthy individuals.

Sociodemographic and clinical data among groups.

| HA | ROP | SCZ | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 45 | N = 43 | N = 63 | ||

| Sociodemographic variables | ||||

| Age | 16.6 (0.9) | 24.3 (5.8) | 42.17 (8.7) | 0.001a,b,c |

| Female gender | 23 (51.1%) | 22 (51.2%) | 32 (50.8%) | 0.999 |

| Marital status | 0.009 | |||

| Single | 39 (86.7%) | 33 (78.6%) | 42 (66.7%) | |

| Couple/married | 6 (13.3%) | 9 (21.4%) | 13 (20.6%) | |

| Separated/divorced | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (12.7%) | |

| Education level | <0.001 | |||

| Primary | 0 (0%) | 6 (14%) | 32 (50.8%) | |

| Secondary | 45 (100%) | 28 (65.1%) | 25 (39.7%) | |

| Tertiary | 0 (0%) | 9 (20.9%) | 8 (9.5%) | |

| Living | <0.001 | |||

| Alone | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | 9 (14.3%) | |

| Family (origin) | 45 (100%) | 36 (83.7%) | 37 (58.7%) | |

| Family (own) | 0 (0%) | 5 (11.5%) | 13 (20.6%) | |

| Institution | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Supported housing | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | 3 (4.8%) | |

| Working status | <0.001 | |||

| Active (student/work) | 45 (100%) | 24 (55.8%) | 1 (1.6%) | |

| Inactive | 0 (0%) | 18 (41.9%) | 13 (20.6%) | |

| Pensioner | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | 49 (77.8%) | |

| Family history of mental disorder | <0.001 | |||

| No | 0 (0%) | 24 (55.8%) | 15 (23.8%) | |

| Yes | 0 (0%) | 16 (37.2%) | 39 (61.9%) | |

| Unknown/unavailable information | 45 (100%) | 3 (7%) | 9 (14.3%) | |

| Cannabis use | 19 (42.2%) | 15 (34.9%) | 6 (9.5%) | <0.001 |

| Clinical variables | ||||

| Cognitive biases (CBQ) | ||||

| CBQ total | 43.7 (7.3) | 40 (5.9) | 46.1 (9.0) | <0.001c |

| Intentionalizing | 7.7 (1.8) | 7.3 (1.1) | 8.5 (1.7) | 0.001b,c |

| Catastrophizing | 9 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.7) | 9.1 (2.4) | 0.013a,c |

| Dichotomous thinking | 8.9 (2.1) | 7.9 (1.8) | 8.9 (2.5) | 0.028c |

| Jumping to conclusions | 10.3 (2.1) | 9.2 (1.9) | 10.6 (2.3) | 0.007c |

| Emotional reasoning | 8.2 (1.9) | 7.6 (2) | 9 (2.6) | 0.009c |

| PANSS factors | ||||

| Positive factor | 4.7 (1.7) | 6.2 (2.2) | <0.001 | |

| Negative factor | 13.4 (6.6) | 12.3 (4.9) | 0.355 | |

| Disorganized factor | 4.7 (1.5) | 5.8 (1.8) | 0.002 | |

| Excited factor | 4.4 (1) | 5.3 (1.6) | 0.001 | |

| Depressed factor | 5.3 (2.4) | 7.5 (6.3) | 0.039 | |

| CDSS | 2.7 (4.2) | 4.8 (4.8) | 0.024 | |

| PSP | 65.5 (16.8) | 58.9 (8.7) | 0.029 | |

| CAPE-42 scores | ||||

| Positive | 1.5 (0.2) | |||

| Negative | 2.6 (0.8) | |||

| Depressive | 1.8 (0.5) | |||

Data are the mean (SD) or N (%).

Abbreviations: SD: standard deviation; HA: healthy adolescents; ROP: recent-onset psychosis; SCZ: schizophrenia; CBQ: Cognitive Biases Questionnaire for Psychosis; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; CDSS: Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; PSP: Personal and Social Performance Scale; CAPE-42: Community Assessment of Psychic Experiences.

Significant (p < 0.05) post hoc comparisons for the ANOVA with a Bonferroni correction are highlighted:

In relation to psychopathology, people with schizophrenia scored higher than ROP individuals in positive, disorganized, excited and depressive symptoms, without significant differences in negative symptoms. People with schizophrenia also had poorer social and overall functioning than ROP subjects.

In the correlation analyses, total cognitive bias scores were associated with positive and depressive symptoms in both healthy adolescents (Table S2) and people with schizophrenia (Table S3), but not in the ROP group. In people with schizophrenia, cognitive biases were also associated with poorer functionality (Table S3).

Regarding each cognitive bias, dichotomous thinking was associated with positive and depressive symptoms in all groups (Tables S2 and S3). In the ROP group, dichotomous thinking was also associated with the PANSS disorganized factor score. Emotional reasoning was associated with negative symptoms in both the schizophrenia and healthy adolescents groups. JTC and catastrophizing correlated with positive symptoms in the schizophrenia group, without associations with psychopathology in the other groups. Intentionality did not correlate with any PANSS factor and only correlated with depressive symptoms and poorer functionality in the schizophrenia group.

In people with ROP, negative and depressive symptoms (CDSS) were associated with poorer functionality (lower PSP scores) (r = −0.576 [p < 0.01] and r = −0.372 [p < 0.05], respectively). In people with schizophrenia, poorer functionality (lower PSP scores) was associated with negative symptoms (r = −0.541, p < 0.01), disorganized symptoms (r = −0.337, p < 0.01), PANSS depressive symptoms (r = −0.266, p < 0.05) and CDSS depressive symptoms (r = −0.338, p < 0.01).

We also explored correlations (Spearman’s) between age and CBQ scores for each group. Total CBQ scores were negatively associated with age in people with a ROP (r = −0.33, p = 0.031) only. In relation to different CBQ domains, age was negatively associated with intentionalizing in healthy adolescents (r = −0.38, p = 0.013), with catastrophizing in people with a ROP (r = −0.35, p = 0.022) and with JTC in people with schizophrenia (r = −0.29, p = 0.021).

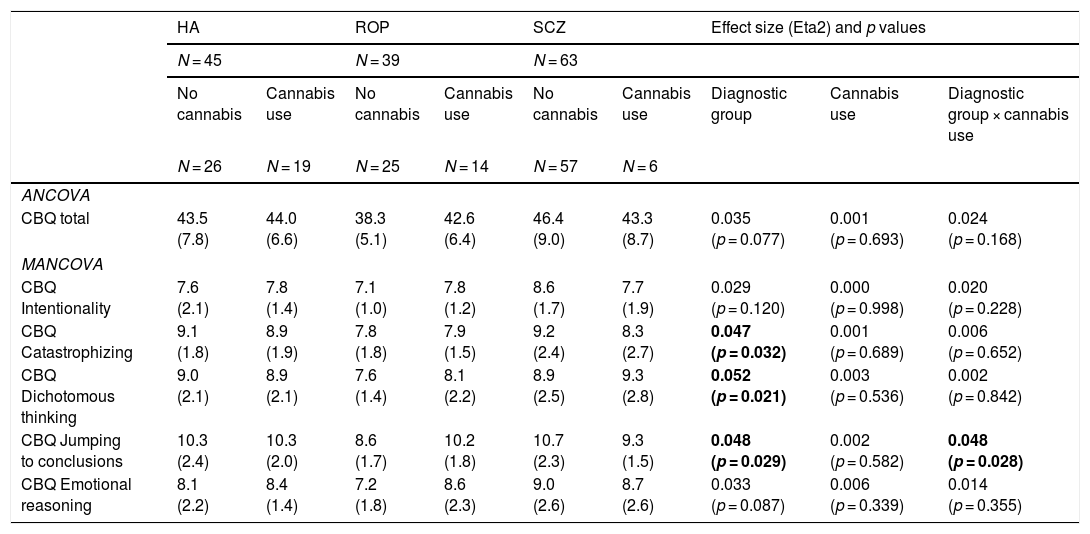

Cognitive biases by cannabis use and diagnostic group: ANCOVA and MANCOVA analysesIn the ANCOVA analyses adjusted for age (Table 2), total cognitive biases were associated with diagnostic group (lower in the ROP group) but not with cannabis use. However, when exploring distinct CBQ dimensions with a MANCOVA, an interaction between cannabis use and diagnostic group was found for JTC (higher in ROP individuals with cannabis use). People with schizophrenia reported more cognitive biases than the ROP group for all the CBQ domains.

Exploration of cognitive biases by cannabis use and diagnostic group adjusted for age.

| HA | ROP | SCZ | Effect size (Eta2) and p values | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 45 | N = 39 | N = 63 | |||||||

| No cannabis | Cannabis use | No cannabis | Cannabis use | No cannabis | Cannabis use | Diagnostic group | Cannabis use | Diagnostic group × cannabis use | |

| N = 26 | N = 19 | N = 25 | N = 14 | N = 57 | N = 6 | ||||

| ANCOVA | |||||||||

| CBQ total | 43.5 (7.8) | 44.0 (6.6) | 38.3 (5.1) | 42.6 (6.4) | 46.4 (9.0) | 43.3 (8.7) | 0.035 (p = 0.077) | 0.001 (p = 0.693) | 0.024 (p = 0.168) |

| MANCOVA | |||||||||

| CBQ Intentionality | 7.6 (2.1) | 7.8 (1.4) | 7.1 (1.0) | 7.8 (1.2) | 8.6 (1.7) | 7.7 (1.9) | 0.029 (p = 0.120) | 0.000 (p = 0.998) | 0.020 (p = 0.228) |

| CBQ Catastrophizing | 9.1 (1.8) | 8.9 (1.9) | 7.8 (1.8) | 7.9 (1.5) | 9.2 (2.4) | 8.3 (2.7) | 0.047 (p = 0.032) | 0.001 (p = 0.689) | 0.006 (p = 0.652) |

| CBQ Dichotomous thinking | 9.0 (2.1) | 8.9 (2.1) | 7.6 (1.4) | 8.1 (2.2) | 8.9 (2.5) | 9.3 (2.8) | 0.052 (p = 0.021) | 0.003 (p = 0.536) | 0.002 (p = 0.842) |

| CBQ Jumping to conclusions | 10.3 (2.4) | 10.3 (2.0) | 8.6 (1.7) | 10.2 (1.8) | 10.7 (2.3) | 9.3 (1.5) | 0.048 (p = 0.029) | 0.002 (p = 0.582) | 0.048 (p = 0.028) |

| CBQ Emotional reasoning | 8.1 (2.2) | 8.4 (1.4) | 7.2 (1.8) | 8.6 (2.3) | 9.0 (2.6) | 8.7 (2.6) | 0.033 (p = 0.087) | 0.006 (p = 0.339) | 0.014 (p = 0.355) |

Abbreviations: HA = healthy adolescents; ROP = recent-onset psychosis; SCZ = schizophrenia; CBQ = Cognitive Biases Questionnaire for Psychosis.

Significant post hoc comparisons (p < 0.05): CBQ Intentionality (SCZ > ROP), CBQ catastrophizing (SCZ > ROP), CBQ Dichotomous thinking (SCZ > ROP), CBQ Jumping to conclusions (SCZ > ROP; SCZ > HA); CBQ Emotional reasoning (SCZ > ROP).

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (bold values).

As an exploratory analysis, we also compared the group of healthy adolescents with high or low psychotic-like experiences (Table S4). Adolescents with more psychotic-like experiences reported more total cognitive biases (CBQ total score) and more emotional reasoning biases. There were no significant differences in negative or depressive symptoms, nor in cannabis use.

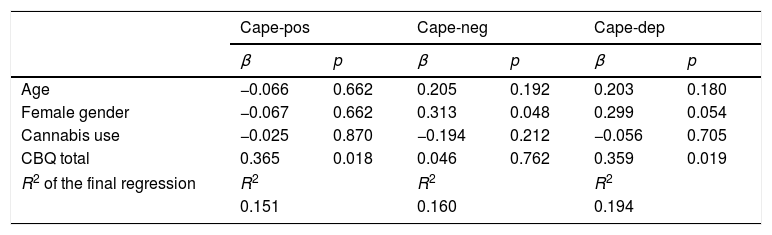

Association between cognitive biases and psychopathology: multiple linear regression analysesIn the multiple linear regression analyses conducted in healthy adolescents, cognitive biases (total CBQ scores) were associated with positive-like experiences and depressive experiences (Table 3).

Linear regression analyses of the relationship between cognitive biases and psychopathology in healthy adolescents while adjusting for covariates.

| Cape-pos | Cape-neg | Cape-dep | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Age | −0.066 | 0.662 | 0.205 | 0.192 | 0.203 | 0.180 |

| Female gender | −0.067 | 0.662 | 0.313 | 0.048 | 0.299 | 0.054 |

| Cannabis use | −0.025 | 0.870 | −0.194 | 0.212 | −0.056 | 0.705 |

| CBQ total | 0.365 | 0.018 | 0.046 | 0.762 | 0.359 | 0.019 |

| R2 of the final regression | R2 | R2 | R2 | |||

| 0.151 | 0.160 | 0.194 | ||||

Abbreviations: β = standardized beta regression coefficient; CBQ total = Cognitive Biases Questionnaire for Psychosis total score; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PANSS-POS = PANSS positive factor; PANSS-NEG = PANSS negative factor; PANSS-DIS = PANSS disorganized factor; PANSS-EXC = PANNS excited factor; PANSS-DEP = PASS depressive factor; CDSS: Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; SCZ: schizophrenia.

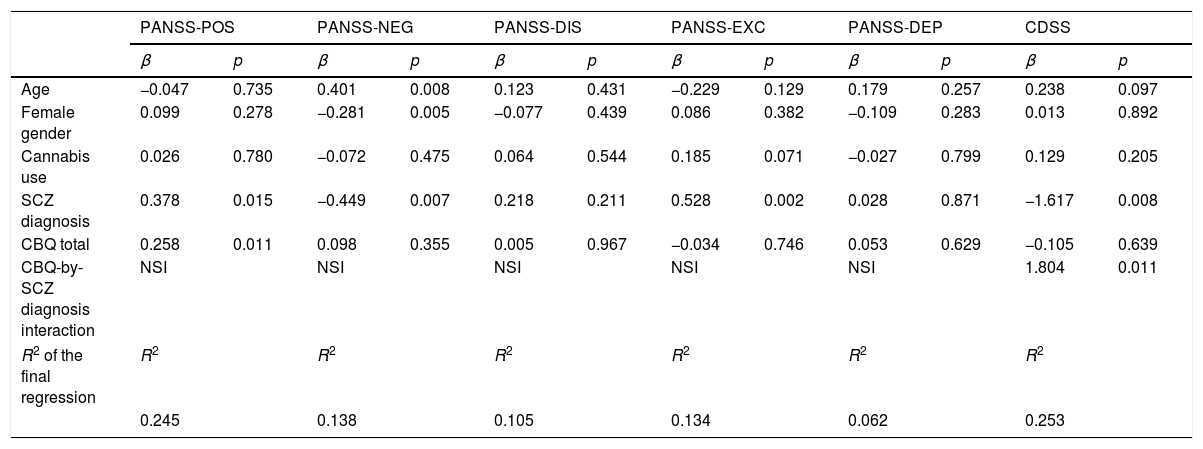

Multiple linear regression analyses of variables predicting psychopathology measured with PANSS and CDSS scales are presented in Table 4. In these analyses, schizophrenia diagnosis was associated with more positive and excited symptoms and fewer negative and depressive symptoms. Cognitive biases (total CBQ score) were positively associated with more positive symptoms. A significant interaction was found between cognitive biases and depressive symptoms, indicating that those individuals with schizophrenia and more cognitive biases also reported more depressive symptoms in the CDSS. This interaction is also described in Fig. 1 in the Supplementary material (Fig. S1).

Linear regression analyses of the relationship between cognitive biases and psychopathology while adjusting for covariates.

| PANSS-POS | PANSS-NEG | PANSS-DIS | PANSS-EXC | PANSS-DEP | CDSS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Age | −0.047 | 0.735 | 0.401 | 0.008 | 0.123 | 0.431 | −0.229 | 0.129 | 0.179 | 0.257 | 0.238 | 0.097 |

| Female gender | 0.099 | 0.278 | −0.281 | 0.005 | −0.077 | 0.439 | 0.086 | 0.382 | −0.109 | 0.283 | 0.013 | 0.892 |

| Cannabis use | 0.026 | 0.780 | −0.072 | 0.475 | 0.064 | 0.544 | 0.185 | 0.071 | −0.027 | 0.799 | 0.129 | 0.205 |

| SCZ diagnosis | 0.378 | 0.015 | −0.449 | 0.007 | 0.218 | 0.211 | 0.528 | 0.002 | 0.028 | 0.871 | −1.617 | 0.008 |

| CBQ total | 0.258 | 0.011 | 0.098 | 0.355 | 0.005 | 0.967 | −0.034 | 0.746 | 0.053 | 0.629 | −0.105 | 0.639 |

| CBQ-by-SCZ diagnosis interaction | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI | 1.804 | 0.011 | |||||

| R2 of the final regression | R2 | R2 | R2 | R2 | R2 | R2 | ||||||

| 0.245 | 0.138 | 0.105 | 0.134 | 0.062 | 0.253 | |||||||

Abbreviations: β = standardized beta regression coefficient; CBQ total = Cognitive Biases Questionnaire for Psychosis total score; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PANSS-POS = PANSS positive factor; PANSS-NEG = PANSS negative factor; PANSS-DIS = PANSS disorganized factor; PANSS-EXC =PANNS excited factor; PANSS-DEP = PASS depressive factor; CDSS: Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia; SCZ: schizophrenia; NSI = non-significant interactions.

Neither cognitive biases, schizophrenia diagnosis nor cannabis use were associated with functionality (data not shown).

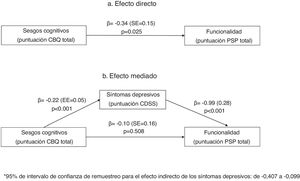

Mediation analysisIn the mediation analysis, we tested whether positive, negative or depressive (CDSS) symptoms were mediators of the relationship between cognitive biases and functionality (PSP score). In a first analysis that included all three mediators, only depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between cognitive biases and functionality (PSP scores). We repeated the analysis including only depressive symptoms as a mediator. As shown in Fig. 1, in the unadjusted model (1a), the CBQ total score was associated with poorer functionality. This effect was fully mediated by the CDSS total score (1b), as the relationship between the CBQ total score and functionality lost its significance when depressive symptoms were included in the equation.

DiscussionThe present study explored the role of cognitive biases in psychopathology in three subgroups of participants: ROP, schizophrenia and healthy adolescents. People with schizophrenia exhibited more cognitive biases than the ROP group. The severity of cognitive biases was significantly associated with positive and depressive symptoms in both people with schizophrenia and healthy adolescents, without an association with depressive symptoms in the ROP group. Furthermore, depressive symptoms mediated the negative relationship between cognitive biases and functionality in people with psychotic disorders.

Cognitive biases by diagnostic groupAlthough we found a higher severity of cognitive biases in people with schizophrenia, we unexpectedly found that healthy adolescents reported more cognitive biases than ROP individuals. To interpret this result, we must first consider that cognitive biases occur in the general population; therefore, their presence alone does not imply psychopathology. A similar Italian study in which a non-clinical population of adolescents and young adults was evaluated using the CBQ scale21 obtained a higher average score than this study (46.1 vs 43.7). In adolescence, these biases may be increased, although this remains to be determined. One explanation could be that depression and anxiety, which affect 10%–20% of children and adolescents globally,38 could be related to an increased score in CBQ. The beginning stage of adulthood, which entails changes and higher social demands, may be associated with increases in anxiety, depression and cognitive biases. The lower proportion of cognitive biases in the ROP group may be explained by the intensive mental health care received at the Early Intervention Service, as all people with a ROP are offered individual and group psychotherapy. This care includes psychoeducational and metacognitive training interventions, which are effective for reducing cognitive biases in people with ROP.39,40 Therefore, a selection bias of the samples could be influencing our results. In line with this possibility, the lower severity of negative symptoms in the schizophrenia group than in the ROP group could also be explained by recruitment and treatment factors. People with schizophrenia were attending a Community Rehabilitation Service daily, which could have translated into improved negative symptom outcomes.

It might also be that other factors not assessed in our study could explain these differences between groups. For instance, the potential contribution of coping skills41 or metacognitive coping strategies42 that might be associated with cognitive biases and psychotic experiences, or social desirability biases, that might be associated with the under-reporting of psychotic experiences.43 A recent study44 has also shown that healthy controls report more JTC biases than people with schizophrenia, which would be in line with our results. The authors concluded that their study challenged the ubiquity of the JTC in psychosis and recommend the study of potential factors contributing to their unexpected result. Another recent study17 has also found that JTC reasoning bias is associated with psychotic-like experiences in healthy controls but not with delusions in people with first-episode psychosis.

Cognitive biases and cannabis useEven though the proportion of cannabis users was higher in healthy adolescents, we failed to find an association with cognitive biases in this group. In contrast, cannabis use was associated with a JTC reasoning style in people with ROP but not in people with schizophrenia. There is scant evidence of cognitive biases related to cannabis, and most of the evidence is concerning attentional bias to the preferential allocation of attention to substance-related stimuli45 and a minor attentional bias towards threat-related stimuli.46

Previous research suggests that cannabis use might mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and psychotic-like experiences in non-clinical populations.22 It could be that cannabis use is associated with a greater risk for psychotic-like experiences or cognitive biases in vulnerable individuals (e.g. people with a history of childhood trauma). In previous studies from our group, we have also found more environmental stress factors (stressful life events and childhood trauma) in cannabis users with ROP (but not in healthy controls), when compared to non-cannabis users.47 As we did not assess the history of childhood trauma in our study, future studies might explore whether this stress-related factor might contribute to the relationship between cannabis use and cognitive biases in people with ROP, in line with previous studies suggesting this link in people with psychotic-like experiences.22

Cognitive biases and psychopathologyWhen exploring the relationship between cognitive biases and psychopathology, JTC showed a positive relationship with positive symptoms in the schizophrenia group but not in the ROP group. These results are in accordance with previous literature in chronic populations, as JTC has been one of the most related biases in psychosis, specifically in people with delusions48 and schizophrenia.49 However, we failed to find a statistically significant association between JTC and positive symptoms in the ROP group, as other studies have reported.14,17,50 Beyond JTC, our results also outline a relationship between total cognitive biases, dichotomous thinking, catastrophizing and positive symptoms in the schizophrenia group. Dichotomous thinking was the bias more clearly associated with positive symptoms in all diagnostic groups, despite scant evidence on this relation in psychosis. Dichotomous thinking and catastrophizing have traditionally been related to depression.51 To our knowledge, there is only one other study that considered a dichotomous thinking style in people with delusions, which suggested that a dichotomous thinking style is related to a lack of belief flexibility.3 Dichotomous thinking might be as well associated with cognitive rigidity,52 which is in line with the lack of cognitive flexibility found people with schizophrenia.53

Furthermore, our study outlines a different pattern of biases related to positive symptoms in ROP versus schizophrenia. Thus, cognitive biases that predominate in the early phase are within the depressive sphere, most likely following the recent diagnosis received and the vital rupture that a first psychotic episode represents. With the progression of ROP to later stages (i.e., a diagnosis of schizophrenia), the pattern of biases reflects a qualitative change towards the traditionally described psychotic thinking and cognitive biases (i.e., JTC, intentionality), probably related to the persistence of delusional beliefs over time. Thus, the presence, severity and type of cognitive biases could be an indicator of the type, severity and chronicity of psychosis. Unexpectedly and despite previous positive reports,15,54,55 intentionality bias was not significantly associated with psychopathology. However, this lack of a statistically significant association may be attributed to a limitation in the sample size.

People with schizophrenia reporting more cognitive biases also reported more depressive symptoms (CDSS score). On the other hand, depressive symptoms were mediators of the relationship between cognitive biases and functionality (PSP score). Depression is common in schizophrenia and is associated with poor quality of life,56 work impairment and overall worse outcomes.57 The role of cognitive biases is thought to be central to the development and maintenance of depression.51,58 Our results have relevant treatment implications. Offering psychological therapy for improving cognitive biases can improve depressive and functional outcomes of people with psychotic disorders. There is strong evidence supporting cognitive behavioural therapy in psychosis. Metacognitive training focuses on modifying cognitive biases and is effective in reducing psychotic symptoms and depression in both people with schizophrenia59 and first psychotic episodes.39,40 Therefore, therapy should be available for these individuals.

LimitationsThis is a cross-sectional study; therefore, there is no evidence of a temporal relationship between the variables considered. Consequently, we cannot establish a cause-and-effect relationship. The healthy adolescent group is a non-probabilistic sampling, potentially producing problems associated with population representativeness and external validity. We included a group of teenagers to study a non-help-seeking group that may experience attenuated psychotic symptoms. Because statistically significant age differences were observed between the groups, we controlled for this variable in the ANCOVA analysis.

Other limitations of our study are not assessing metacognitive coping strategies or social desirability bias, which could explain some differences found in cognitive biases between groups. Multivariate analyses were not adjusted by general intelligence (IQ), which might be considered another limitation. However, participants with intellectual disabilities were excluded from the study.

We also assessed psychopathology symptoms with different scales (PANSS and CDSS in patients; CAPE in healthy adolescents). Although the CAPE was designed to assess psychic experiences in the community, previous studies suggest that CAPE-positive subscale shows high correlation with specific scales for psychotic symptoms (Peters Delusions Inventory) in university students31 and the CAPE-depressive scale also correlates with specific depressive scales (Beck Depression Inventory) in people with mood disorders.60

The limitations notwithstanding, the present study constitutes an attempt to characterize cognitive biases and their relationship with psychotic symptoms, depression and functionality in people with ROP and schizophrenia. Different patterns and their relation to the progression or chronicity of the disease could be established. The greater severity of cognitive biases in the adolescent group is an intriguing finding that needs to be replicated in future studies. Although non-clinical and clinical groups are different in terms of age or duration of illness, the shared association between cognitive biases and depressive symptoms underscores the importance of cognitive biases on mood.

ContributorsJavier Labad, José Antonio Monreal and Montserrat Pàmias designed the study. Maribel Ahuir, Josep Maria Crosas, Francesc Estrada, Wanda Zabala, Sara Pérez-Muñoz, Meritxell Tost, Alba González-Fernández, Raquel Aguayo, Estefania Gago and Maria José Miñano participated in the recruitment of participants. Javier Labad, Maribel Ahuir and Itziar Montalvo analyzed the data. Maribel Ahuir reviewed the scientific literature and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in the discussion of the results and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThis study was supported in part by grants from the Carlos III Health Institute through the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (PI15/01386 and PI18/01843), the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) “A way to build Europe”, and the Catalan Agency for the Management of University and Research Grants (AGAUR 2017 SGR 632). Javier Labad and Itziar Montalvo received an Intensification of the Research Activity Grant (SLT006/17/00012; SLT008/18/00074) by the Health Department of the Generalitat de Catalunya during 2018 and 2019.

The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Ahuir M, Crosas JM, Estrada F, Zabala W, Pérez-Muñoz S, González-Fernández A, et al. Los sesgos cognitivos están asociados a las variables clínicas y funcionales en la psicosis: comparación entre esquizofrenia, psicosis temprana e individuos sanos. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2021;14:4–15.