To determine whether second-generation-antipsychotics (SGAs) are effective for negative symptoms treatment in schizophrenia.

MethodsTwo meta-analyses were carried out using placebo or haloperidol as comparators. The search included the following databases: Pubmed, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Proquest Health and Medical Complete, Science Citation Index Expanded, and Current Contents Connect. The outcome measure used was the change in negative symptoms, choosing a standardized statistic (Cohen's d) to synthesize the data.

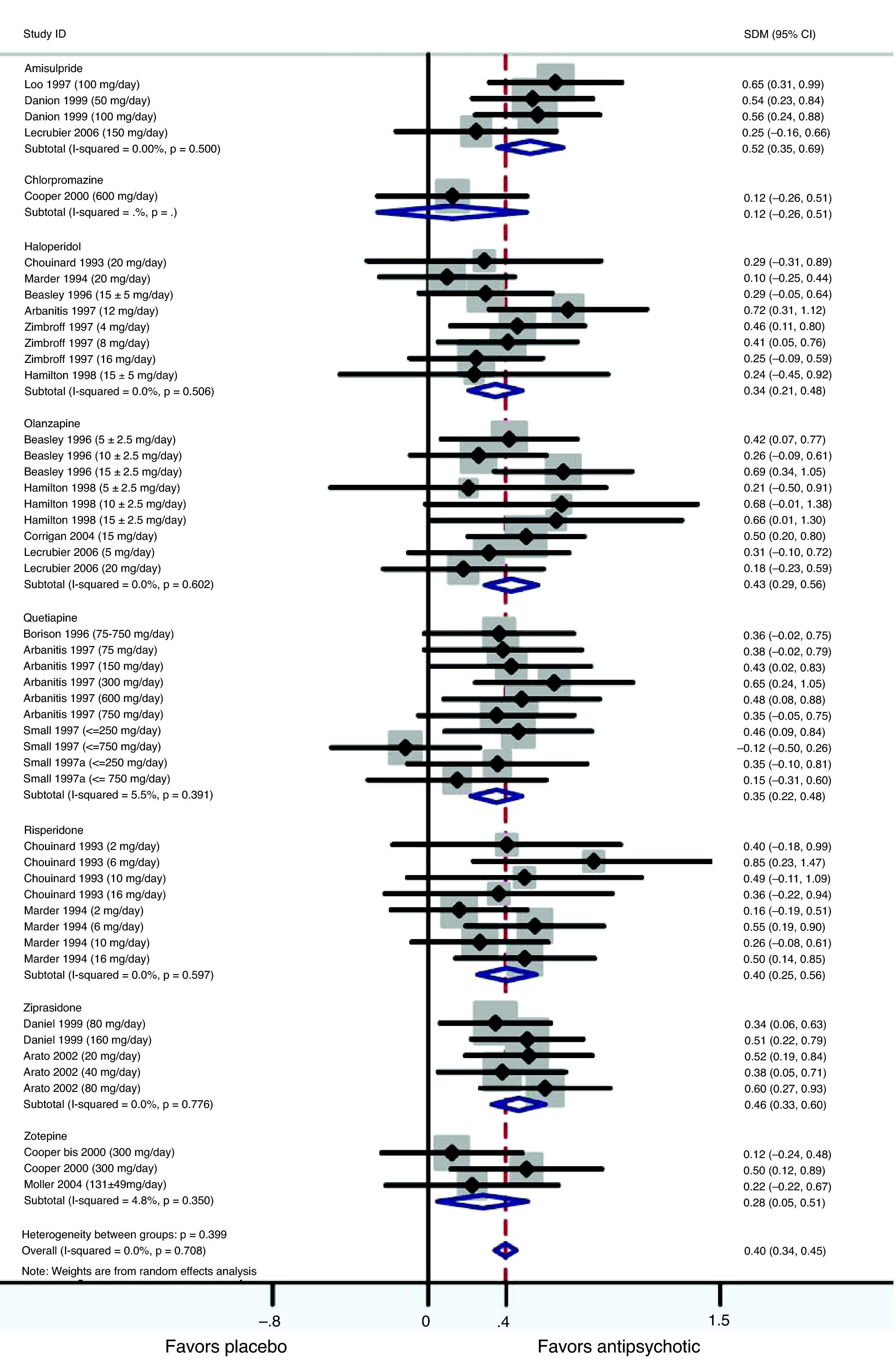

ResultsIn the placebo-controlled meta-analysis, the effect sizes (Cohen's d) obtained for amisulpride, haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone were 0.52, 0.34, 0.43, 0.36, 0.40 and 0.46, respectively, favoring active treatment against placebo (P<0.001 in all cases). The haloperidol-controlled meta-analysis only showed a statistically significant trend favoring antipsychotics over haloperidol (Cohen's d=0.15).

ConclusionsMost antipsychotics (amisulpride, haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone and ziprasidone) are effective in the treatment of negative symptoms. Amisulpride and ziprasidone showed higher effect sizes.

Determinar si los antipsicóticos de segunda generación (ASG) son eficaces para el tratamiento de los síntomas negativos de esquizofrenia.

MétodosSe llevaron a cabo dos metaanálisis en los que se utilizó placebo o haloperidol para establecer comparaciones. Se realizaron búsquedas en las siguientes bases de datos: Pubmed, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Proquest Health and Medical Complete, Science Citation Index Expanded, y Current Contents Connect. La variable medida utilizada fue el cambio de los síntomas negativos, eligiendo un estadístico muestral normalizado (d de Cohen) para sintetizar los datos.

ResultadosEn el metaanálisis controlado con placebo, los tamaños del efecto (d de Cohen) que se obtuvieron con amisulprida, haloperidol, olanzapina, quetiapina, risperidona y ziprasidona fueron 0,52, 0,34, 0,43, 0,36, 0,40 y 0,46 respectivamente, unos resultados favorables al tratamiento activo respecto al placebo (p<0,001 en todos los casos). El metaanálisis controlado con haloperidol solo mostró una tendencia estadísticamente significativa favorable a los antipsicóticos respecto al haloperidol (d de Cohen=0,15).

ConclusionesLa mayoría de los antipsicóticos (amisulprida, haloperidol, olanzapina, quetiapina, risperidona y ziprasidona) son eficaces en el tratamiento de los síntomas negativos. El tamaño del efecto fue mayor con la amisulprida y la ziprasidona.

Negative symptoms are intrinsic to the pathology of schizophrenia and are associated with significant deficits in motivation, verbal and nonverbal communication, affect, and cognitive and social functioning.1 Negative symptoms of schizophrenia are debilitating and contributing to poor outcomes and functioning in schizophrenia.2 Underlying mechanisms of negative symptoms are not well understood. Several hypotheses suggested the association of negative symptoms with abnormalities in the integration of emotion and cognition that have long been considered the hallmark characteristics of schizophrenia.3

Second generation antipsychotic (SGA) medications have been claimed to be more efficacious than conventional antipsychotics for the treatment of negative symptoms, based on a variety of studies with different designs and duration. However, the initial enthusiasm for SGAs as powerful agents to improve negative symptoms has given way to relative pessimism that the effects of current pharmacological treatments could be at best modest.4 Description of clinical trials in this field must include both the dose used and the duration of the trial because of the occurrence of decreases in secondary negative symptoms when the dose of conventional antipsychotic is low or the duration of trial is longer.5

The aim of this study was to examine the efficacy of antipsychotics in the treatment of negative symptoms. The methodology used was a meta-analysis, and following two meta-analyses were carried out: one considering placebo-controlled trials and the other considering haloperidol-controlled trials. Meta-analysis is a powerful instrument: the results can be strongly conclusive when no marked variation in results across the different studies is observed. It also has an important and obvious advantage in comparison with conventional reviews, which only give qualitative estimates of treatment effects.

Experimental proceduresSearchThe following databases were searched for clinical trials usingno restrictions on publication date or sample size (N): Pubmed (from 1/1966 to 6th November 2006), The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (current version, last search 6th November 2006), Proquest Health and Medical Complete (from 1971 to 31st October 2006), Science Citation Index Expanded (from 1945 to 6th November 2006), and Current Contents Connect (from 1998 to 6th November 2006). Studies were also identified by cross-referencing other studies found in the databases as described above. Search terms used were “schizophrenia negative trial” and “schizophrenia negative trial placebo”.

SelectionStudies included in our analyses were placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized-clinical-trials (RCTs) assessing the efficacy of antipsychotics which met the following criteria: (1) the study sample was diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to the DSM-IV, DSM-III-R or ICD-10 criteria; (2) outcomes on efficacy in negative symptoms were assessed and reported; (3) English language articles; (4) patients were not receiving more than one antipsychotic medication during the trial (monotherapy). Studies with any of the following characteristics were excluded from the analyses: (1) open-label studies; (2) treatment-resistant population; (3) with a history of unresponsiveness to any antipsychotic medication, and those studies including patients; (4) diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder; (5) with a diagnosis of delusional disorder; (6) with substance abuse or dependence; (7) taking anxiolytics, antidepressants or mood stabilizers during the study period; (8) trials with a duration of less than six weeks. We also excluded studies, only after failing to get information from the authors after contacting them when insufficient data on variability were reported for our outcome. Studies were also excluded when they examined unlicensed indications or non-marketed medications. The search and selection of the studies were performed by two researchers and in case any discrepancy on the inclusion of a study existed (only selected by one of the researchers) agreement on the inclusion or exclusion followed upon agreement with clinicians.

Study characteristicsThe outcome of interest was the mean change in score from baseline to endpoint for negative symptoms. All extracted data on efficacy from the original trials corresponded to an intention to treat (ITT) analysis, meaning that the data were analyzed for all randomly assigned patients who had at least one post-randomization efficacy assessment. This type of analysis is preferable to a completer analysis, which includes only data on those participants who completed the trial and therefore create potential bias in the results. A last observation carried forward (LOCF) basis was used in all trials, i.e. when a patient prematurely withdrew from the study, their data were included in the endpoint analyses using data carried forward from the final evaluation.

Several scales and subscales for the assessment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia exist. However most common scales and those which appear in the studies included in our meta-analysis were: the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS)6 and the modified version of the Modified Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS summary),7 which is the sum of the SANS global ratings, the negative subscale of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS-N),8 and the retardation factor of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS-R), which is the sum of items 3, 13 and 16 on the BPRS9: emotional withdrawal, motor retardation, and blunted affect.

Among the articles identified using the databases as mentioned before, several were discarded for the following reasons: (1) type of article (reviews, meta-analyses and path analytic approaches); (2) evaluating efficacy of medications other than antipsychotics; or (3) studying other diseases (not schizophrenia, e.g. schizotypal personality disorder).

Quantitative data synthesisThe meta-analyses compared SGAs to placebo or haloperidol. The standardized mean difference (SMD) used was Cohen's d10 in both meta-analyses. A standardized statistic was chosen to enable combination of results of different scales assessing the same outcome. Positive values of the SMD indicate effects that favor the antipsychotic, and negative values effects favoring the placebo or haloperidol. A random effects model was applied, following the Der-Simonian and Laird method.11 This approach is preferable to a fixed effects approach which involves the assumption that the effects being estimated in the different studies are identical. For testing heterogeneity between studies the Cochran's Q statistic12 and the I2 test13 were used. I2 was calculated as, I2=max (0, 100×(Q−df)/Q) where Q is the Cochran's statistic and df are the degrees of freedom (number of studies−1). I2 is preferred over the Q test, since the Q test is known to be poor at detecting true heterogeneity when dealing with a small number of studies, which is often the case with meta-analyses. Publication bias was assessed by means of Begg's and Egger's tests.14,15

The meta-analyses performed were stratified with outcomes grouped by drug using placebo or haloperidol in the control arms, i.e. risperidone versus placebo and olanzapine versus haloperidol. To perform a meta-analysis with continuous data using SMD, the standard deviation (SD) of the mean change for every treatment arm was needed. In case trials did not report this information, and if it was not possible to obtain these data from the authors, p-values were used to estimate the average standard deviation (SD) for the experimental and the control arms. The 95% confidence intervals were used; p-values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All calculations were performed using STATA (StataCorp version 8.2).

ResultsStudies excluded from the meta-analysesPlacebo-controlled trialsAfter the first selection process, 43 studies were retrieved for more detailed evaluation. Of these, five studies were excluded because they did not report outcomes on scales or subscales of negative symptoms, five studies were excluded because their population included patients with schizophreniform disorder or schizotypal personality disorder, two studies were excluded because their population was neuroleptic treatment resistant or intolerant, two studies were excluded because they had a crossover design, two studies were excluded because their trial duration was less than 6 weeks, two other studies were excluded because they only examined medications not marketed: fananserin and sertindole. One study was excluded because some patients received antidepressants during the trial. Finally, three studies had to be excluded, after failure to contact the authors, because insufficient measures of variability of negative symptoms were reported.

Haloperidol-controlled trialsAfter a first selection process, based on the same criteria used in the selection of placebo-controlled trials, 26 studies were retrieved for more detailed evaluation. Of these, five studies were excluded because they did not report outcomes on scales of negative symptoms, another five studies were excluded because their population included patients with schizophreniform disorder, and three studies were excluded because their population was neuroleptic treatment resistant. One of these three studies was Breier et al.,16 whose population was formed of partial-responders. Another study of Zimbroff et al.17 was excluded from the haloperidol-controlled meta-analysis because it examined only sertindole versus haloperidol. Another study was excluded because it did not report data on change in score in negative symptoms, the outcome of interest. One study was excluded because some patients received antidepressants during the trial and another one because it did not have a double-blind design, but only a rather-blind design. Finally, one study had to be excluded, after contacting authors, because insufficient measures of variability of negative symptoms were reported.

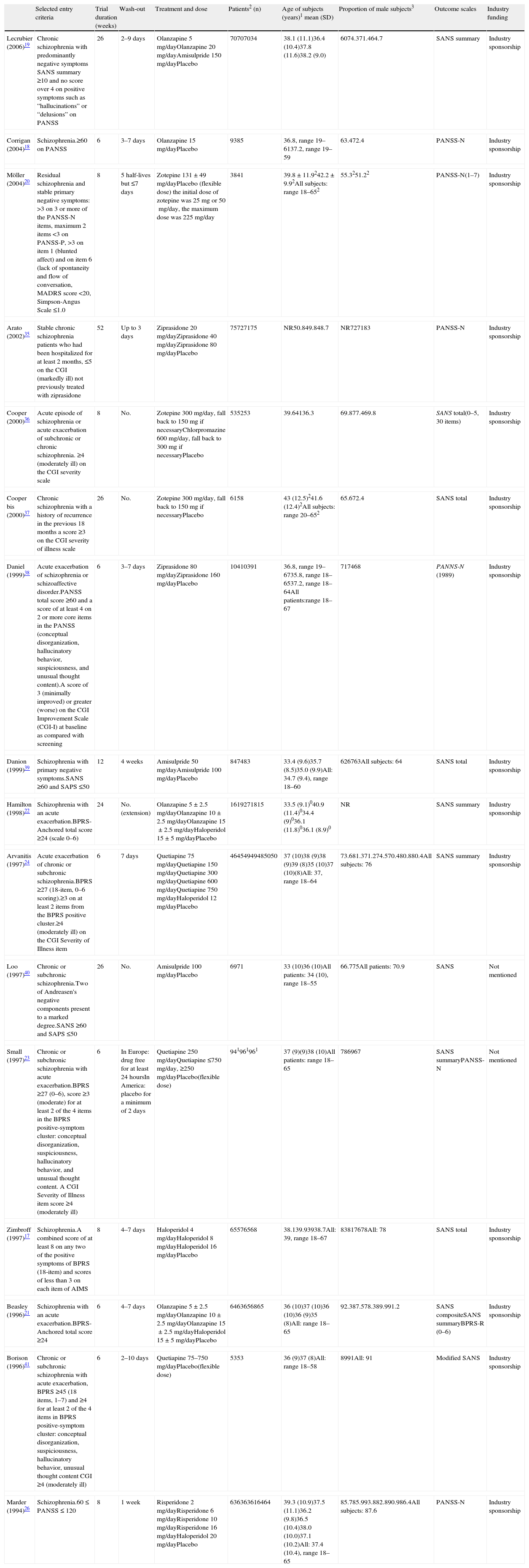

Studies included in the meta-analysis comparing placebo versus active treatmentThe studies included in this meta-analysis are listed and described in Table 1. Altogether, 18 articles reporting efficacy in negative symptoms; 16 studies, of both first and second generation antipsychotics were found: 3 of amisulpride, 6 of haloperidol, 4 of olanzapine, 4 of quetiapine, 2 of ziprasidone, 3 of zotepine, 2 of risperidone, and 1 of chlorpromazine (some studies reported results on more than one antipsychotic). All studies were placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind and including monotherapy. The duration of the double-blind period varied from 6 weeks to one year. The diagnosis of schizophrenia was made according to the DSM-III-R (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) in all trials, with the exceptions of Corrigan et al.,18 Lecrubier et al.,19 Zimbroff et al.,17 and Möller et al.20 that used DSM-IV, both DSM-III-R and DSM-IV, and ICD-10, respectively. Use of concomitant medications for treating insomnia, anxiety, EPS (extrapyramidal symptoms) or akathisia was permitted in most of the trials. With regard to the setting variation across studies existed: some included only inpatient populations, some only outpatients, and some both in- and out-patients. All data included in the meta-analysis were obtained using an intent-to-treat (ITT) last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) analysis, meaning that the analyses included all randomized patients with a baseline and at least one post baseline measure. If a patient was withdrawn from the study, the last observation was carried forward and used in the endpoint analysis. In the Möller et al.20 study, promethazine was used as a concomitant medication by one patient in the placebo group. Promethazine has anticholinergic effects. Previously it was used as an antipsychotic but it has only approximately 1/10 of the antipsychotic effect of chlorpromazine. Although both ITT and per protocol data analyses were reported in Lecrubier et al.,19 only data from the ITT analysis were used in the meta-analysis. In Zimbroff et al.17 and Corrigan et al.,18 sertindole and sonepiprazole results were not extracted, as sertindole was withdrawn from the market on December 2, 1998 due to concerns over the risk of cardiac arrhythmia and sudden death. Sonepiprazole is not effective for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Beasley et al.21 and Hamilton et al.22 published data from the same trial: Beasley et al. reported results on the acute phase of the trial and Hamilton et al.22 on the responder extension of the same trial. Although in Beasley et al.21 outcome on efficacy in negative symptoms was presented using BPRS-R (BPRS retardation factor), SANS-composite and SANS-summary, only data from one of these scales were used in the meta-analysis. The SANS-summary was chosen in order to obtain homogeneity in the set of scales used in this study. Both PANSS-N and SANS summary data from Small et al.23 were used in the meta-analysis since they corresponded to different population sets: PANSS-N was used for the European population and SANS-summary for the American population.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies.

| Selected entry criteria | Trial duration (weeks) | Wash-out | Treatment and dose | Patients2 (n) | Age of subjects (years)1 mean (SD) | Proportion of male subjects3 | Outcome scales | Industry funding | |

| Lecrubier (2006)19 | Chronic schizophrenia with predominantly negative symptoms SANS summary ≥10 and no score over 4 on positive symptoms such as “hallucinations” or “delusions” on PANSS | 26 | 2–9 days | Olanzapine 5mg/dayOlanzapine 20mg/dayAmisulpride 150mg/dayPlacebo | 70707034 | 38.1 (11.1)36.4 (10.4)37.8 (11.6)38.2 (9.0) | 6074.371.464.7 | SANS summary | Industry sponsorship |

| Corrigan (2004)18 | Schizophrenia.≥60 on PANSS | 6 | 3–7 days | Olanzapine 15mg/dayPlacebo | 9385 | 36.8, range 19–6137.2, range 19–59 | 63.472.4 | PANSS-N | Industry sponsorship |

| Möller (2004)20 | Residual schizophrenia and stable primary negative symptoms: >3 on 3 or more of the PANSS-N items, maximum 2 items <3 on PANSS-P, >3 on item 1 (blunted affect) and on item 6 (lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation, MADRS score <20, Simpson-Angus Scale ≤1.0 | 8 | 5 half-lives but ≤7 days | Zotepine 131±49mg/dayPlacebo (flexible dose) the initial dose of zotepine was 25mg or 50mg/day, the maximum dose was 225mg/day | 3841 | 39.8±11.9242.2±9.92All subjects: range 18–652 | 55.3251.22 | PANSS-N(1–7) | Industry sponsorship |

| Arato (2002)35 | Stable chronic schizophrenia patients who had been hospitalized for at least 2 months, ≤5 on the CGI (markedly ill) not previously treated with ziprasidone | 52 | Up to 3 days | Ziprasidone 20mg/dayZiprasidone 40mg/dayZiprasidone 80mg/dayPlacebo | 75727175 | NR50.849.848.7 | NR727183 | PANSS-N | Industry sponsorship |

| Cooper (2000)36 | Acute episode of schizophrenia or acute exacerbation of subchronic or chronic schizophrenia. ≥4 (moderately ill) on the CGI severity scale | 8 | No. | Zotepine 300mg/day, fall back to 150mg if necessaryChlorpromazine 600mg/day, fall back to 300mg if necessaryPlacebo | 535253 | 39.64136.3 | 69.877.469.8 | SANS total(0–5, 30 items) | Industry sponsorship |

| Cooper bis (2000)37 | Chronic schizophrenia with a history of recurrence in the previous 18 months a score ≥3 on the CGI severity of illness scale | 26 | No. | Zotepine 300mg/day, fall back to 150mg if necessaryPlacebo | 6158 | 43 (12.5)241.6 (12.4)2All subjects: range 20–652 | 65.672.4 | SANS total | Industry sponsorship |

| Daniel (1999)38 | Acute exacerbation of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.PANSS total score ≥60 and a score of at least 4 on 2 or more core items in the PANSS (conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, suspiciousness, and unusual thought content).A score of 3 (minimally improved) or greater (worse) on the CGI Improvement Scale (CGI-I) at baseline as compared with screening | 6 | 3–7 days | Ziprasidone 80mg/dayZiprasidone 160mg/dayPlacebo | 10410391 | 36.8, range 19–6735.8, range 18–6537.2, range 18–64All patients:range 18–67 | 717468 | PANNS-N (1989) | Industry sponsorship |

| Danion (1999)39 | Schizophrenia with primary negative symptoms.SANS ≥60 and SAPS ≤50 | 12 | 4 weeks | Amisulpride 50mg/dayAmisulpride 100mg/dayPlacebo | 847483 | 33.4 (9.6)35.7 (8.5)35.0 (9.9)All: 34.7 (9.4), range 18–60 | 626763All subjects: 64 | SANS total | Industry sponsorship |

| Hamilton (1998)22 | Schizophrenia with an acute exacerbation.BPRS-Anchored total score ≥24 (scale 0–6) | 24 | No.(extension) | Olanzapine 5±2.5mg/dayOlanzapine 10±2.5mg/dayOlanzapine 15±2.5mg/dayHaloperidol 15±5mg/dayPlacebo | 1619271815 | 33.5 (9.1)040.9 (11.4)034.4 (9)036.1 (11.8)036.1 (8.9)0 | NR | SANS summary | Industry sponsorship |

| Arvanitis (1997)24 | Acute exacerbation of chronic or subchronic schizophrenia.BPRS ≥27 (18-item, 0–6 scoring).≥3 on at least 2 items from the BPRS positive cluster.≥4 (moderately ill) on the CGI Severity of Illness item | 6 | 7 days | Quetiapine 75mg/dayQuetiapine 150mg/dayQuetiapine 300mg/dayQuetiapine 600mg/dayQuetiapine 750mg/dayHaloperidol 12mg/dayPlacebo | 46454949485050 | 37 (10)38 (9)38 (9)39 (8)35 (10)37 (10)(8)All: 37, range 18–64 | 73.681.371.274.570.480.880.4All subjects: 76 | SANS summary | Industry sponsorship |

| Loo (1997)40 | Chronic or subchronic schizophrenia.Two of Andreasen's negative components present to a marked degree.SANS ≥60 and SAPS ≤50 | 26 | No. | Amisulpride 100mg/dayPlacebo | 6971 | 33 (10)36 (10)All patients: 34 (10), range 18–55 | 66.775All patients: 70.9 | SANS | Not mentioned |

| Small (1997)23 | Chronic or subchronic schizophrenia with acute exacerbation.BPRS ≥27 (0–6), score ≥3 (moderate) for at least 2 of the 4 items in the BPRS positive-symptom cluster: conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behavior, and unusual thought content. A CGI Severity of Illness item score ≥4 (moderately ill) | 6 | In Europe: drug free for at least 24 hoursIn America: placebo for a minimum of 2 days | Quetiapine 250mg/dayQuetiapine ≤750mg/day, ≥250mg/dayPlacebo(flexible dose) | 941961961 | 37 (9)(9)38 (10)All patients: range 18–65 | 786967 | SANS summaryPANSS-N | Not mentioned |

| Zimbroff (1997)17 | Schizophrenia.A combined score of at least 8 on any two of the positive symptoms of BPRS (18-item) and scores of less than 3 on each item of AIMS | 8 | 4–7 days | Haloperidol 4mg/dayHaloperidol 8mg/dayHaloperidol 16mg/dayPlacebo | 65576568 | 38.139.93938.7All: 39, range 18–67 | 83817678All: 78 | SANS total | Industry sponsorship |

| Beasley (1996)21 | Schizophrenia with an acute exacerbation.BPRS-Anchored total score ≥24 | 6 | 4–7 days | Olanzapine 5±2.5mg/dayOlanzapine 10±2.5mg/dayOlanzapine 15±2.5mg/dayHaloperidol 15±5mg/dayPlacebo | 6463656865 | 36 (10)37 (10)36 (10)36 (9)35 (8)All: range 18–65 | 92.387.578.389.991.2 | SANS compositeSANS summaryBPRS-R (0–6) | Industry sponsorship |

| Borison (1996)41 | Chronic or subchronic schizophrenia with acute exacerbation, BPRS ≥45 (18 items, 1–7) and ≥4 for at least 2 of the 4 items in BPRS positive-symptom cluster: conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behavior, unusual thought content CGI ≥4 (moderately ill) | 6 | 2–10 days | Quetiapine 75–750mg/dayPlacebo(flexible dose) | 5353 | 36 (9)37 (8)All: range 18–58 | 8991All: 91 | Modified SANS | Industry sponsorship |

| Marder (1994)26 | Schizophrenia.60≤PANSS≤120 | 8 | 1 week | Risperidone 2mg/dayRisperidone 6mg/dayRisperidone 10mg/dayRisperidone 16mg/dayHaloperidol 20mg/dayPlacebo | 636363616464 | 39.3 (10.9)37.5 (11.1)36.2 (9.8)36.5 (10.4)38.0 (10.0)37.1 (10.2)All: 37.4 (10.4), range 18–65 | 85.785.993.882.890.986.4All subjects: 87.6 | PANSS-N | Industry sponsorship |

SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; SANS summary, sum of SANS global ratings; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; BPRS-R, sum of emotional withdrawal, motor retardation and blunted effect items on the BPRS; BPRS-A, BPRS-Anchored; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PANSS-N, PANSS negative subscale; PANSS-P, PANSS positive subscale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; SAPS, Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; AIMS, Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale; QLS, Quality of Life Scale; MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (64); Simpson-Angus Scale (65); NR, not reported.

(0) Data regarding those patients with a baseline and at least one post baseline QLS assessment; (1) at baseline; (2) regarding patients included in the analyses; (3) all data are given as a percentage.

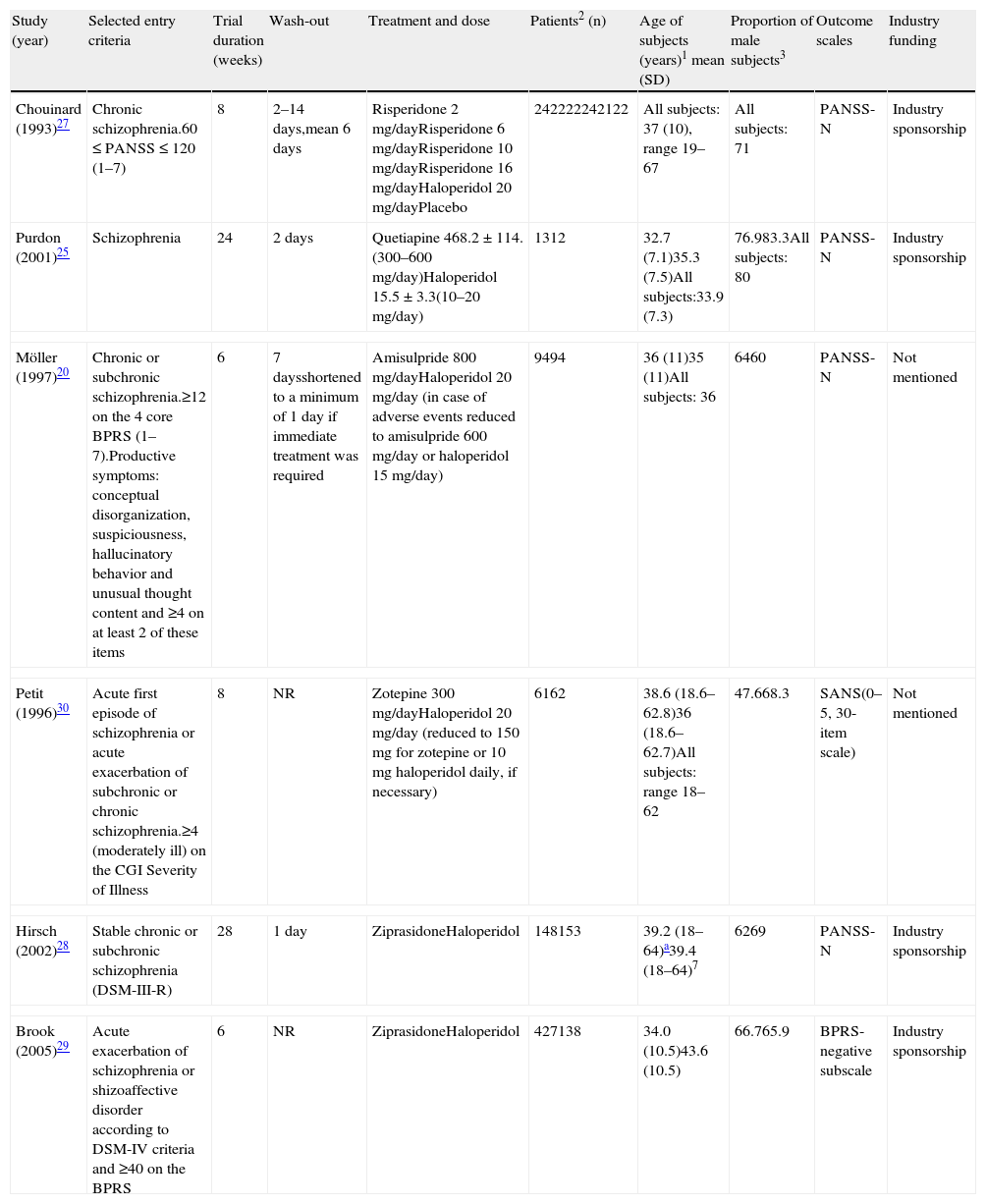

This meta-analysis took data from 10 articles that were comparing haloperidol over a second generation antipsychotic (SGA): 2 for olanzapine,21,22 2 for quetiapine,24,25 2 for risperidone,26,27 2 for ziprasidone,28,29 one for amisulpride,20 and one for zotepine.30 Marder et al.,26 Arvanitis et al.,23 Beasley et al.,21 Hamilton et al.,22 and Chouinard et al.27 had already been included in the meta-analysis of placebo-controlled clinical trials and their characteristics are located in Table 1. For Purdon et al.,25 Möller et al.,20 Hirsch et al.,27 Brook et al.29 and Petit et al.,30 see Table 2. All studies were haloperidol-controlled, randomized and monotherapy. The duration of the double-blind period varied from 6 weeks to 6 months. The diagnosis of schizophrenia was made according to the DSM-III-R (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) in all trials, with the exception of Purdon et al.25 that used the DSM-IV. Also, as in the meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials, in most of the trials the use of concomitant medications for treating insomnia, anxiety, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) or akathisia was permitted. Some trials included only inpatient populations, some only outpatients, and some both in- and out-patients. All data included in the meta-analysis was obtained using an intent-to-treat (ITT) last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) analysis, with the exception of Hirsch et al.28 study. Purdon et al.25 study was included in the meta-analysis despite its small sample size (No.=25). Petit et al.30 study was included in the meta-analysis although no information was reported on drug abuse or dependence status of patients; a statement that patients with alcohol abuse or dependence were excluded from the trial was included. Brook et al.29 study was included in the meta-analysis although it was not double blind because all assessments were conducted by evaluators blinded to drug allocation. See also the notes of Beasley et al.21 and Hamilton et al.22 reported in the previous section on included studies comparing placebo versus active treatment.

Characteristics of some of the studies included in the meta-analysis of haloperidol-controlled trials.

| Study (year) | Selected entry criteria | Trial duration (weeks) | Wash-out | Treatment and dose | Patients2 (n) | Age of subjects (years)1 mean (SD) | Proportion of male subjects3 | Outcome scales | Industry funding |

| Chouinard (1993)27 | Chronic schizophrenia.60≤PANSS≤120 (1–7) | 8 | 2–14 days,mean 6 days | Risperidone 2mg/dayRisperidone 6mg/dayRisperidone 10mg/dayRisperidone 16mg/dayHaloperidol 20mg/dayPlacebo | 242222242122 | All subjects: 37 (10), range 19–67 | All subjects: 71 | PANSS-N | Industry sponsorship |

| Purdon (2001)25 | Schizophrenia | 24 | 2 days | Quetiapine 468.2±114.(300–600mg/day)Haloperidol 15.5±3.3(10–20mg/day) | 1312 | 32.7 (7.1)35.3 (7.5)All subjects:33.9 (7.3) | 76.983.3All subjects: 80 | PANSS-N | Industry sponsorship |

| Möller (1997)20 | Chronic or subchronic schizophrenia.≥12 on the 4 core BPRS (1–7).Productive symptoms: conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behavior and unusual thought content and ≥4 on at least 2 of these items | 6 | 7 daysshortened to a minimum of 1 day if immediate treatment was required | Amisulpride 800mg/dayHaloperidol 20mg/day (in case of adverse events reduced to amisulpride 600mg/day or haloperidol 15mg/day) | 9494 | 36 (11)35 (11)All subjects: 36 | 6460 | PANSS-N | Not mentioned |

| Petit (1996)30 | Acute first episode of schizophrenia or acute exacerbation of subchronic or chronic schizophrenia.≥4 (moderately ill) on the CGI Severity of Illness | 8 | NR | Zotepine 300mg/dayHaloperidol 20mg/day (reduced to 150mg for zotepine or 10mg haloperidol daily, if necessary) | 6162 | 38.6 (18.6–62.8)36 (18.6–62.7)All subjects: range 18–62 | 47.668.3 | SANS(0–5, 30-item scale) | Not mentioned |

| Hirsch (2002)28 | Stable chronic or subchronic schizophrenia (DSM-III-R) | 28 | 1 day | ZiprasidoneHaloperidol | 148153 | 39.2 (18–64)a39.4 (18–64)7 | 6269 | PANSS-N | Industry sponsorship |

| Brook (2005)29 | Acute exacerbation of schizophrenia or shizoaffective disorder according to DSM-IV criteria and ≥40 on the BPRS | 6 | NR | ZiprasidoneHaloperidol | 427138 | 34.0 (10.5)43.6 (10.5) | 66.765.9 | BPRS-negative subscale | Industry sponsorship |

SANS, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms; BPRS, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PANSS-N, PANSS negative subscale; CGI, Clinical Global Impression; NR, not reported.

(0) Data regarding those patients with a baseline and at least one post baseline QLS assessment; (1) At baseline; (2) regarding patients included in the analyses; (3) all data are given as a percentage.

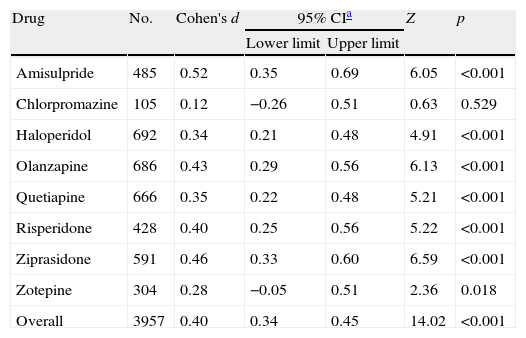

When pooling data from all placebo-controlled studies together, a moderate and significant overall effect size (Cohen's d=0.40, 95% CI 0.34–0.45, p<0.001) was obtained favouring active treatment over placebo (Fig. 1). Q and I2 tests did not detect significant heterogeneity between studies (Q=41.27.07, df=47, p=0.708, I2=0%). Also an analysis stratified by drug was carried out. For the amisulpride group a significant moderate pooled standardized mean difference was obtained, favouring active treatment over placebo against negative symptoms: Cohen's d=0.52 (95% CI 0.35–0.69, p<0.001) (Table 2) indicating that the mean of the amisulpride group was approximately at the 70th percentile of the placebo group. Similar results were obtained for ziprasidone (Cohen's d=0.46, 95% CI 0.33–0.60, p<0.001) (Table 3), as well as for olanzapine group (Cohen's d=0.43, 95% CI 0.29–0.56, p<0.001) and risperidone (Cohen's d=0.40, 95% CI 0.25–0.56, p<0.001) groups. The effect sizes for haloperidol and quetiapine were statistically significant and low-to-moderate: Cohen's d=0.34 (95% CI 0.21–0.48, p<0.001) and Cohen's d=0.35 (95% CI 0.22–0.48, p<0.001), respectively. Results from the zotepine analysis showed only a statistically significant trend favouring active treatment over placebo (zotepine: Cohen's d=0.28, 95% CI −0.05 to 0.51, p=0.018) (Table 2). Only data from one trial were available for the chlorpromazine analysis (chlorpromazine: Cohen's d=0.12, 95% CI −0.26 to 0.51, p=0.529). The I2 test for heterogeneity gives the percentage of total variation across studies that are due to heterogeneity rather than chance. The results of the I2 test did not reveal the presence of important inconsistency in findings. The most significant values regarding heterogeneity were obtained in the quetiapine and zotepine groups (I2=5.5% and I2=4.8%, respectively), indicating just a small amount of heterogeneity.

Forest plot using a random effects model stratified by drug for studies listed in Table 1.

Meta-analysis of antipsychotics versus placebo on negative symptoms.

| Drug | No. | Cohen's d | 95% CIa | Z | p | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Amisulpride | 485 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.69 | 6.05 | <0.001 |

| Chlorpromazine | 105 | 0.12 | −0.26 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 0.529 |

| Haloperidol | 692 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 4.91 | <0.001 |

| Olanzapine | 686 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.56 | 6.13 | <0.001 |

| Quetiapine | 666 | 0.35 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 5.21 | <0.001 |

| Risperidone | 428 | 0.40 | 0.25 | 0.56 | 5.22 | <0.001 |

| Ziprasidone | 591 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.60 | 6.59 | <0.001 |

| Zotepine | 304 | 0.28 | −0.05 | 0.51 | 2.36 | 0.018 |

| Overall | 3957 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 14.02 | <0.001 |

Z and p are the statistic and the p-value for the test of significance of the effect size Cohen's d.

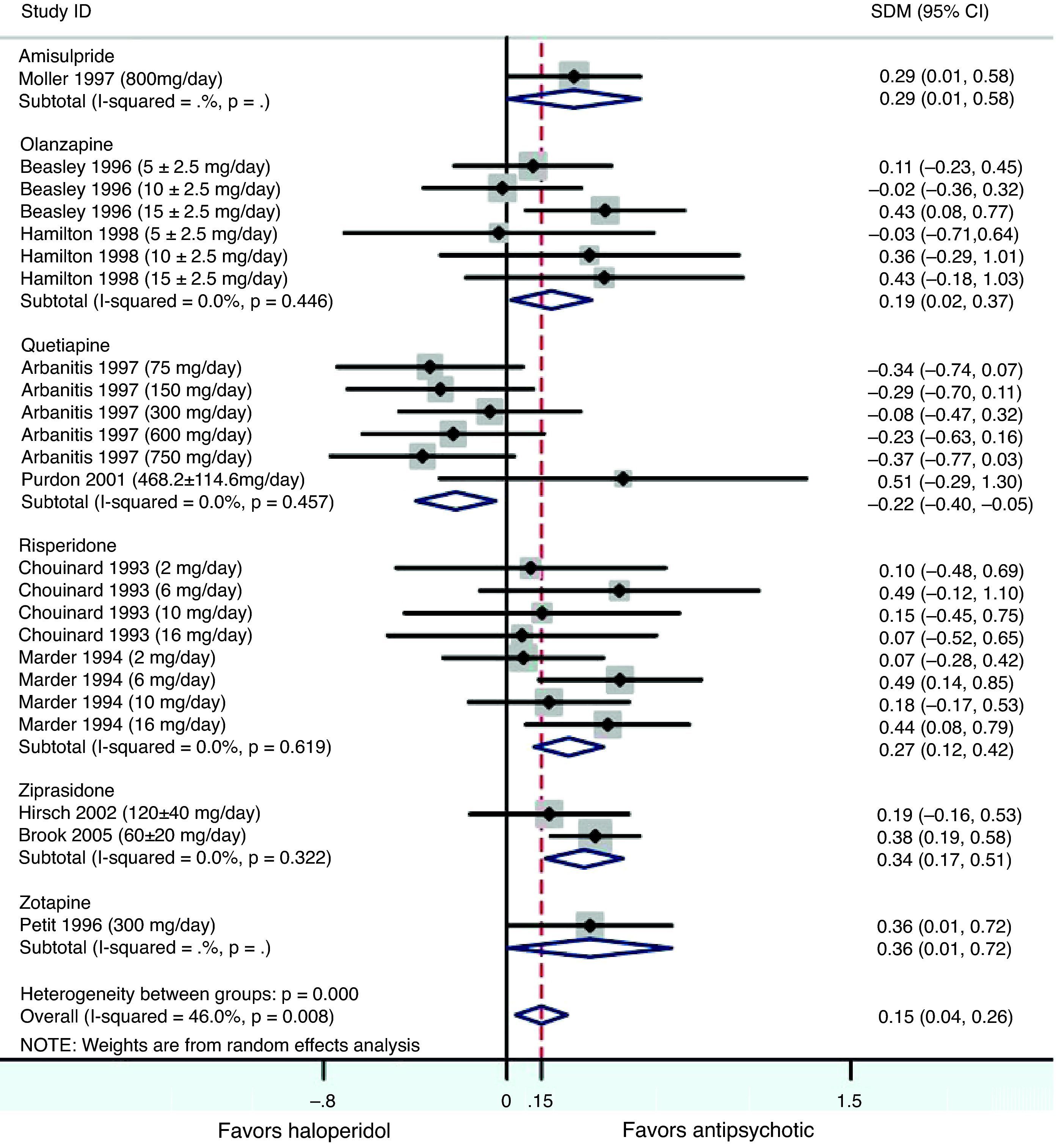

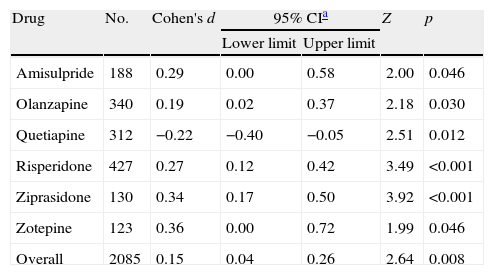

Results obtained after pooling standardized mean differences (SMD) from all studies comparing SGA's against haloperidol, showed a statistically significant trend favouring SGA's over haloperidol in the treatment of negative symptoms (Cohen's d=0.15, 95% CI 0.04–0.26, p=0.008; Table 4 and Fig. 2). An important amount of heterogeneity was detected in this global analysis with both Q and I2 tests (Q=42.56, df=23, p=0.008, I2=46.0%) possibly due to real significant differences in treatment effects between different SGA's against haloperidol. In the stratified sub analysis, where comparisons were grouped by drug, the conclusions obtained were as following: For the ziprasidone, risperidone and olanzapine groups a significant low and low-to-moderate standardized mean difference was found (SMD) favouring SGA [Cohen's d=0.34 (95% CI 0.17–0.50, p<0.001); 0.27 (0.12–0.42, p<0.001) and 0.19 (0.02–0.37, p=0.030), respectively]. Conversely, in the quetiapine analysis a low standardized mean difference (SMD) was obtained but this time favouring haloperidol over the SGA (d=−0.22 [−0.40 to (−0.05)], p=0.012). Only data from one trial were available for the amisulpride [d=0.29 (0.00–0.58), p=0.046] and zotepine [d=0.36 (0.00–0.72), p=0.046] analyses (Table 4). All the above described analyses were repeated, excluding Purdon et al.,25 whose data were not normally distributed due to the small sample size, and almost identical results were obtained. In this report only pooled data containing Purdon et al.25 are reported.

Meta-analysis of second generation antipsychotics versus haloperidol on negative symptoms.

| Drug | No. | Cohen's d | 95% CIa | Z | p | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Amisulpride | 188 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 2.00 | 0.046 |

| Olanzapine | 340 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.37 | 2.18 | 0.030 |

| Quetiapine | 312 | −0.22 | −0.40 | −0.05 | 2.51 | 0.012 |

| Risperidone | 427 | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.42 | 3.49 | <0.001 |

| Ziprasidone | 130 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.50 | 3.92 | <0.001 |

| Zotepine | 123 | 0.36 | 0.00 | 0.72 | 1.99 | 0.046 |

| Overall | 2085 | 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.26 | 2.64 | 0.008 |

Z and p are the statistic and the p-value for the test of significance of the effect size Cohen's d.

Meta-analysis is a powerful instrument, but there are also important limitations applicable to these kinds of techniques. First, their quality depends directly on the quality of the studies that are included and secondly, it makes the assumption that data in the studies follow a normal distribution, which may not be true in studies with small sample sizes15 as was the case in the Purdon et al.25 study. As a low weight was assigned to the Purdon et al.25 study and it did not significantly influence the results. Meta-analysis has a lower power when only a few studies are available. For example, in the placebo-controlled meta-analysis chlorpromazine group, and in the haloperidol-controlled meta-analysis amilsupride and zotapine groups were composed of data from only one study each. Publication of new randomized clinical trials regarding efficacy of antipsychotics in negative symptoms in schizophrenia could significantly change the results obtained here.

Heterogeneity, which leads to inconclusive results, is another source of possible limitation for meta-analyses.14 Heterogeneity may be due to a variety of reasons such as differences in patient characteristics between studies, differences in study design, and differences in the instruments used to assess the outcome of interest.31 In this meta-analysis variation exists in population characteristics (Tables 1 and 2),31 the duration of trials which ranges from 6 weeks to one year and scarcity of studies reporting data with sufficient detail on negative symptoms forcing the mixing of results from different assessment instruments: PANSS-N, SANS, and BPRS retardation factor (BPRS-R). BPRS-R was used in two studies although it is relatively insensitive when used alone to measure changes in negative symptoms.32 In this study, the tests of heterogeneity performed in the meta-analysis with placebo in the control arm did not show the presence of important heterogeneity, contrary to the results obtained in the meta-analysis of haloperidol-controlled studies. In this case, an important amount of heterogeneity was detected as shown in Table 4. This could be due to real differences in treatment effects for different SGAs over haloperidol.

Publication bias may have skewed results as only the English published literature is included in our study. Often negative results from small studies tend not to be published and researchers whose mother tongue is not English are more likely to publish their non-significant results in non-English written journals.33 Two tests of bias (Begg's and Egger's) were carried out, but no significant results were obtained. However these tests are known to have low power and therefore it was not possible to estimate the magnitude of the publication bias.

Data on eight different antipsychotics were synthesized in the first meta-analysis on treatment efficacy in negative symptoms of schizophrenia that used placebo in the control arm (typical antipsychotics: haloperidol and chlorpromazine; atypical antipsychotics: amisulpride, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone and zotepine). However, the subgroup analysis for chlorpromazine (as shown in Table 3) was based on only one study each so it would be inappropriate to draw conclusions from results for this drug. More trials evaluating effects of chlorpromazine against negative symptoms should be carried out and included in later meta-analyses. No trials identified using our search strategy examining clozapine efficacy fulfilled our inclusion criteria. Data on six different SGAs were synthesized in our meta-analysis on treatment efficacy in negative symptoms of schizophrenia that used haloperidol in the control arm: amisulpride, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone and zotepine.

Overall results obtained in the meta-analysis comparing antipsychotics versus placebo suggested that some antipsychotics (amisulpride, haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone and zotepine) are effective in the treatment of negative symptoms. Effect sizes for these antipsychotics ranged from d=0.28 to d=0.52, so although efficacy is statistically significant only moderate or low effect sizes were obtained. These data do not support the idea of non-efficacy for the treatment of negative symptoms for first generation antipsychotics (FGAs). Haloperidol was found to have equivalent efficacy in negative symptoms treatment compared with quetiapine and was better than zotepine. However the SGAs amisulpride, ziprasidone, olanzapine and risperidone were more effective in treating negative symptoms than haloperidol. Overall results obtained in the second meta-analysis suggested that SGAs are better than haloperidol in treating negative symptoms. However, the global standardized mean difference (SMD) was small and some important heterogeneity was detected in the tests which suggests that superior efficacy depends on the second generation antipsychotic (SGA) used in the experimental arm. Data obtained in the meta-analysis of haloperidol-controlled clinical trials confirm the findings in the meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies: the superiority of some second generation antipsychotics (SGAs) such as amisulpride, olanzapine, risperidone, ziprasidone and zotepine over haloperidol in the treatment of negative symptoms. Moreover, the results in the meta-analysis of haloperidol-controlled studies suggested that haloperidol is more effective than the SGA quetiapine, whereas in the meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies these drugs seemed to have equivalent efficacy. However, all results obtained in the meta-analysis of haloperidol-controlled clinical trials must be interpreted with caution, as the number of studies included in this meta-analysis was relatively small. Another limitation of this study could be that no analysis of the influence of the doses of haloperidol has been performed, it is not clear if it could have had effect on the on the results. As high doses of haloperidol have demonstrated to have side effects which might confound the measures of effectiveness on negative symptoms.

Results from both meta-analyses support those obtained in Davis et al.34 which showed that both olanzapine and risperidone were moderately superior to FGAs on negative symptoms.

To conclude, three main conclusions can be extracted from both meta-analyses: (1) most antipsychotics (amisulpride, haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone and zotepine) are significantly effective in the treatment of negative symptoms, but their efficacy seems to be product-dependent; (2) amisulpride and ziprasidone showed slightly better outcomes than the remainder; (3) a statistically significant trend favouring SGA's over haloperidol in the treatment of negative symptoms was shown.

FundingThis study has been funded by Pfizer Spain.

Conflict of interestJavier Rejas is an employee of Pfizer Spain. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors wish to thank all physician participants in the study as well as Lisette Kaskens of BCN Health Economics and Outcomes Research for their contribution to the goals of study.

Please cite this article as: Darbà J, et al. Eficacia de los antipsicóticos de segunda generación en el tratamiento de los síntomas negativos de esquizofrenia: un metaanálisis de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2011;4(3):126–43.