Suicidal and self-injurious behaviours in adolescents are a major public health concern. However, the prevalence of self-injurious thoughts and behaviours in Spanish outpatient adolescents is unknown.

MethodsA total of 267 adolescents between 11 and 18 years old were recruited from the Child and Adolescent Outpatient Psychiatric Services, Jiménez Díaz Foundation (Madrid, Spain) from November 1, 2011 to October 31, 2012. All participants were administered the Spanish version of the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviours Inventory, which is a structured interview that assesses the presence, frequency, and characteristics of suicidal ideation, suicide plans, suicide gestures, suicide attempts, and non-suicidal self-injury.

ResultsOne-fifth (20.6%) of adolescents reported having had suicidal ideation at least once during their lifetime. Similarly, 2.2% reported suicide plans, 9.4% reported suicide gesture, 4.5% attempted suicide, and 21.7% reported non-suicidal self-injury, at least once during their lifetime. Of the whole sample, 47.6% of adolescents reported at least one of the studied thoughts or behaviours in their lifetime. Among them, 47.2% reported two or more of these thoughts or behaviours. Regarding the reported function of each type of thoughts and behaviours examined, most were performed for emotional regulation purposes, except in the case of suicide gestures (performed for the purposes of social reinforcement).

ConclusionsThe high prevalence and high comorbidity of self-injurious thoughts and behaviours, together with the known risk of transition among them, underline the need of a systematic and routine assessment of these thoughts and behaviours in adolescents assessed in mental health departments.

Las conductas suicidas y autoagresivas de los adolescentes suponen un importante problema de salud pública. Sin embargo, se desconoce en nuestro medio, la prevalencia y funciones de la ideación así como de las conductas suicidas y autoagresivas en la población adolescente atendida en Salud Mental.

MétodosUn total de 267 adolescentes de entre 11 y 18 años fueron reclutados de las consultas ambulatorias del Servicio de Psiquiatría de la Fundación Jiménez Díaz del 1 de noviembre de 2011 al 31 de octubre de 2012. Se administró a todos los pacientes la Escala de Pensamientos y Conductas Autolesivas que evalúa la presencia, frecuencia y características de la ideación suicida, la planificación suicida, los gestos de suicidio, los intentos de suicidio y las autolesiones sin intención suicida.

ResultadosUn 20,6% de los adolescentes afirmaron haber tenido ideación suicida, un 2,2% planes suicidas, un 9,4% gestos suicidas, un 4,5% intentos de suicidio y un 21,7% autolesiones al menos una vez a lo largo de su vida. El 47,6% de los adolescentes refirieron haber tenido a lo largo de su vida al menos una de las conductas estudiadas y el 47,2% de ellos señalaron dos ó más de estas conductas. En relación a la función atribuida a las conductas examinadas, la mayor parte se realizaron con la intención de regular emociones, a excepción de los gestos suicidas (que mostró una función relacionada con el contexto social).

ConclusionesDadas las elevadas cifras en población clínica de prevalencia y comorbilidad, unido al conocido riesgo de transición de unas conductas autoagresivas a otras, se recomienda la evaluación sistemática y rutinaria de dichas conductas en los adolescentes atendidos en salud mental.

Suicidal behaviour in adolescents represents an important public health issue. Although Spain has one of the lowest suicide mortality rates, it has recently experienced an increase in comparison with other countries.1 In fact, the Spanish Statistical Office determines that suicide is the second external cause of death among adolescents and young adults aged 15–19 years old.2 Moreover, the adolescence period entails a particularly significant risk for other self-destructive behaviour (SDBs); self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention are particularly predominant during that stage. Rates in this evolutionary period range from 5% to 37% approximately in community samples,3 opposite to the 4% prevalence estimation in the adult population.4 As self-inflicted lesions tend to occur between the ages of 12 and 14 years old,5 adolescence is a critical period both for research and clinical care of SDBs.6

Despite the indicated data, some ways of self-destruction, such as suicidal gestures and self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention, have received relatively little attention by researchers. Those who have attempted to commit suicide tend to develop more fatal self-inflicted lesions,7,8 so their risk of death caused by suicide is higher.9–11 Although the data focus on the need to distinguish between behaviour with suicidal intention (such as suicidal attempts) and that without suicidal intention (such as suicidal gestures), most previous studies have not established this difference.12

On the other hand, a significant limitation of most researches on the prevalence of suicidal behaviour is that they employ instruments that assess a very limited range of said behaviour. As stated by Nock and Prinstein,13 most of the previous studies did not employ a direct or systematic assessment of the self-inflicted lesions, but rather they used the clinical case study format14 or studies carried out through surveys.15 In the recent bibliography on self-inflicted lesions, some authors have found a very wide range of variability that could be mostly due to the different assessment methods used; in particular, prevalence was lower when a unique question with dichotomous response instead of examinations with multiple items or behaviour listings had been used.3 Thus, the development of reliable comparisons in studies made with community as well as clinical populations could be facilitated by the use of instruments that accurately examine the presence, frequency and characteristics of SDBs, such as the interview used in this study (the Spanish adaptation of Nock et al's Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviours [SITBI],12 carried out by our team16).

The main objective of our study is to determine the prevalence of a wide set of self-destructive behaviour in a clinical sample made up by the adolescents who required the treatment provided by the ambulatory mental health services. Furthermore, as a secondary objective, we want to examine the functions and triggering factors referred by the adolescents themselves for each of the SDBs. The fact that someone would want to inflict lesions upon him/herself is difficult to comprehend, so a possible way of explaining this behaviour is to consider the functions that that person could be fulfilling at a particular moment. This knowledge is important not only at a theoretical level but also, fundamentally, at a clinical level, as it could guide the intervention.

Material and methodsProcedureA total of 267 subjects were recruited in the external offices of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Unit of Fundación Jiménez Díaz (Jiménez Díaz Foundation), from November 1, 2011 to October 31, 2012, after they and their relatives or legal representatives were informed about the study and the informed consent was obtained. Patients under 11 years old, over 18 years old and/or with difficulties in comprehending the questionnaires employed in the study were excluded. The Ethics Committee at Fundación Jiménez Díaz approved the study.

All patients were provided with the “Escala de Pensamientos y Conductas Autolesivas”,16 which is a Spanish adaptation of the SITBI.12 It is a self-applied questionnaire that we administer in our study as a structured interview. It assesses the presence, frequency and characteristics of suicidal ideation (thoughts about ending with one's life17: “Have you ever thought about killing yourself?”16), suicidal planning (design of a concrete suicidal method17: “Have you ever devised a plan to commit suicide? Have you ever thought about killing yourself?”16), suicidal gestures (action that pretends to have a suicidal intention but whose end is different than dying18: “Have you ever done something so that someone believed you wished to kill yourself when indeed you did not have any intention of doing it?”16), suicidal attempts (self-injurious behaviours where the subject has the intention to die18: “Have you ever attempted suicide with a real intention to die?”16) and self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention (self-inflicting behaviour where the person has no intention of dying17: “Have you ever suffered self-inflicted lesions?”16). The functions explored are: automatic negative reinforcement (“to stop the bad feelings”16), automatic positive reinforcement (“to feel something” or “to mitigate the feeling of emptiness”16), social negative reinforcement (“to escape from others” or “to avoid doing something”16) and social positive reinforcement (“to communicate something to others” or “to get attention from others”16). The causes examined are: family problems, problems with friends, problems with the partner, problems with peers, problems at school/work and an altered mental state.

The socio-demographic data, both the medical and psychiatric clinical records and the family history were obtained through a questionnaire devised to that end. Obstetric complications were assessed using items from the Obstetric Complications Scale.19 The presence of vital stressful events was assessed through the Vital Events Scale (VES).20 The diagnoses were assigned by experimented clinicians, who also completed the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAFS)21 and the Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGIS),22 to estimate the global degree of functioning and the severity of symptomatology.

Statistical analysisThe descriptive statistical data (mean, typical deviation and prevalence) were estimated for the socio-demographic characteristics, history and clinical characteristics.

Subsequently, the descriptive statistical data (mean, typical deviation and prevalence) for each of the SDBs were examined. To examine the differences in gender and age in the SDBs, data were analysed comparing the means through the Chi square test (χ2). To examine the causes and functions reported for each SDB, an analysis was made using the analysis of variance (ANOVA).

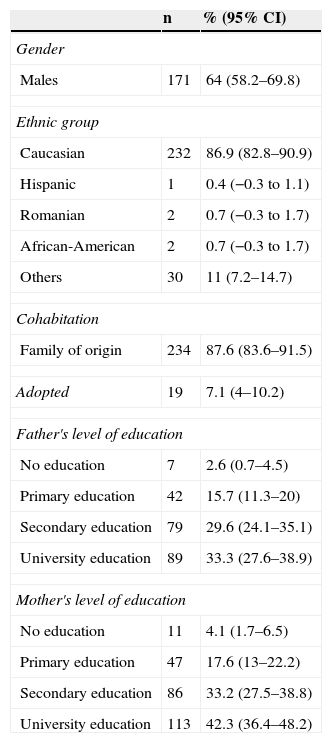

ResultsSocio-demographicThe study participants featured 267 adolescents that attended the ambulatory mental health services. Most of them were males (64%; 95% CI 58.2–69.8), Caucasian (86.9%; 95% CI 82.8–90.9) and lived with their family of origin (87.6%, 95% CI 83.6–91.5). 7.2% (95% CI 4–10.2) were adopted. The mean age was 14.2 (1.9) years old. Other socio-demographic characteristics can be seen in Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (No.=267).

| n | % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Males | 171 | 64 (58.2–69.8) |

| Ethnic group | ||

| Caucasian | 232 | 86.9 (82.8–90.9) |

| Hispanic | 1 | 0.4 (−0.3 to 1.1) |

| Romanian | 2 | 0.7 (−0.3 to 1.7) |

| African-American | 2 | 0.7 (−0.3 to 1.7) |

| Others | 30 | 11 (7.2–14.7) |

| Cohabitation | ||

| Family of origin | 234 | 87.6 (83.6–91.5) |

| Adopted | 19 | 7.1 (4–10.2) |

| Father's level of education | ||

| No education | 7 | 2.6 (0.7–4.5) |

| Primary education | 42 | 15.7 (11.3–20) |

| Secondary education | 79 | 29.6 (24.1–35.1) |

| University education | 89 | 33.3 (27.6–38.9) |

| Mother's level of education | ||

| No education | 11 | 4.1 (1.7–6.5) |

| Primary education | 47 | 17.6 (13–22.2) |

| Secondary education | 86 | 33.2 (27.5–38.8) |

| University education | 113 | 42.3 (36.4–48.2) |

| Mean (TD) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 14.21 (1.9) | 13.9–14.4 |

TD: typical deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

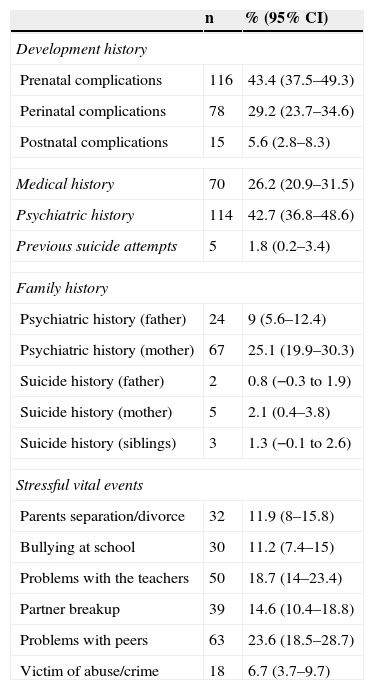

The mothers of 43.3% of the participants reported prenatal complications (95% CI 37.5–49.3%), such as preeclampsia or bleeding during pregnancy. Besides, 29.2% had experienced perinatal complications (95% CI 23.7–34.6) such as emergency caesarean.

42.7% of the adolescents (95% CI 36.8–48.6) had a history of psychiatric treatment. Moreover, 25.2% of the participants’ mothers (95% CI 19.9–30.3) and 9% of the fathers (95% CI 5.6–12.4) had a history of psychiatric treatment.

Regarding the vital stressful events that occurred during the last 3 years, problems with peers were the most frequently reported event by adolescents (23.6% of the sample; 95% CI 18.5–28.7). On the other hand, nearly 7% of the adolescents (6.7%; 95% CI 3.7–9.7) claimed that they had been victims of some crime or abuse in the last 3 years. Table 2 shows detailed information of the participants’ history.

Clinical history of the participants (No.=267).

| n | % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Development history | ||

| Prenatal complications | 116 | 43.4 (37.5–49.3) |

| Perinatal complications | 78 | 29.2 (23.7–34.6) |

| Postnatal complications | 15 | 5.6 (2.8–8.3) |

| Medical history | 70 | 26.2 (20.9–31.5) |

| Psychiatric history | 114 | 42.7 (36.8–48.6) |

| Previous suicide attempts | 5 | 1.8 (0.2–3.4) |

| Family history | ||

| Psychiatric history (father) | 24 | 9 (5.6–12.4) |

| Psychiatric history (mother) | 67 | 25.1 (19.9–30.3) |

| Suicide history (father) | 2 | 0.8 (−0.3 to 1.9) |

| Suicide history (mother) | 5 | 2.1 (0.4–3.8) |

| Suicide history (siblings) | 3 | 1.3 (−0.1 to 2.6) |

| Stressful vital events | ||

| Parents separation/divorce | 32 | 11.9 (8–15.8) |

| Bullying at school | 30 | 11.2 (7.4–15) |

| Problems with the teachers | 50 | 18.7 (14–23.4) |

| Partner breakup | 39 | 14.6 (10.4–18.8) |

| Problems with peers | 63 | 23.6 (18.5–28.7) |

| Victim of abuse/crime | 18 | 6.7 (3.7–9.7) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

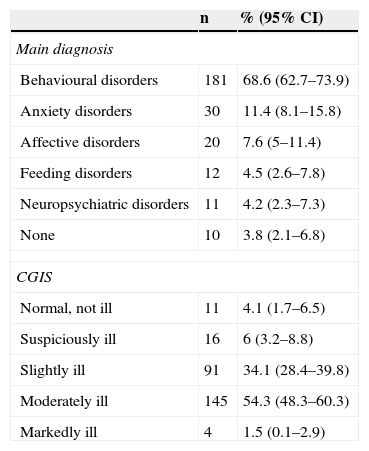

As shown in Table 3, 68.6% of the adolescents (95% CI 62.7–73.9) were diagnosed with some kind of behavioural disorder, followed by anxiety disorders (11.4%; 95% CI 8.1–15.8) and mood disorders (7.6%; 95% CI 5–7.8). Eating behaviour disorders affected 4.5% (95% CI 2.6–7.8) of the subjects. Finally, 4.2% (95% CI 2.3–7.3) were diagnosed with some type of neuropsychiatric disorder. Regarding the severity of the symptoms, 54.3% (95% CI 48.3–60.3) were categorised as moderately ill and 34.1% (95% CI 28.4–39.8) as slightly ill.

Clinical characteristics of the participants (No.=267).

| n | % (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Main diagnosis | ||

| Behavioural disorders | 181 | 68.6 (62.7–73.9) |

| Anxiety disorders | 30 | 11.4 (8.1–15.8) |

| Affective disorders | 20 | 7.6 (5–11.4) |

| Feeding disorders | 12 | 4.5 (2.6–7.8) |

| Neuropsychiatric disorders | 11 | 4.2 (2.3–7.3) |

| None | 10 | 3.8 (2.1–6.8) |

| CGIS | ||

| Normal, not ill | 11 | 4.1 (1.7–6.5) |

| Suspiciously ill | 16 | 6 (3.2–8.8) |

| Slightly ill | 91 | 34.1 (28.4–39.8) |

| Moderately ill | 145 | 54.3 (48.3–60.3) |

| Markedly ill | 4 | 1.5 (0.1–2.9) |

| Mean (TD) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Months under treatment | 12.56 (11.92) | 10.5–13.4 |

| GAFS | 67.27 (10.87) | 65.9–68.6 |

GAFS: Global Assessment of Functioning Scale; CGIS: Clinical Global Impressions Scale; TD: typical deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Behavioural disorders: hyperkinetic disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, substance abuse disorder and other behavioural disorders. Anxiety disorders: phobic anxiety disorders, obsessive–compulsive disorder and other anxiety disorders, adaptation disorder and somatomorphic disorder. State of mind disorders: mood disorders. Eating behavioural disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and not specified eating behavioural disorders. Neuropsychiatric disorders: generalised developmental disorders, mental disability, learning disorders, tics and other diagnoses not included.

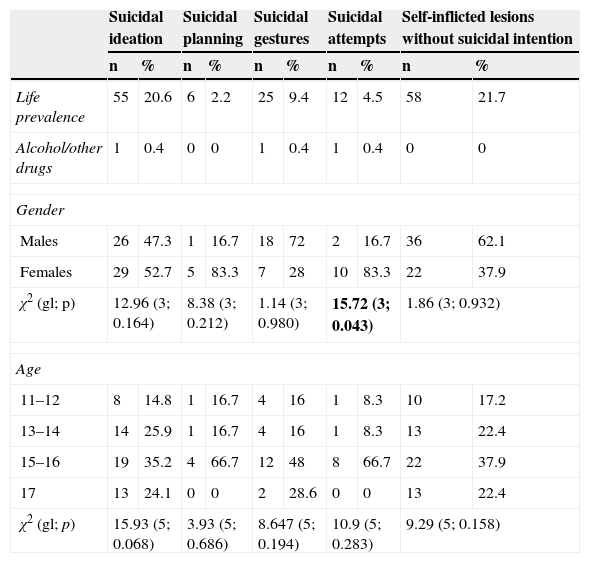

The frequencies, means and typical deviations of the adolescents’ responses to the SITBI questionnaire are shown in Table 4. 4.5% of the adolescents reported some suicidal attempt throughout their lives. 20.6% reported suicidal ideation at some point in their lives. Furthermore, 21.7% of the participants had suffered self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention at some point in their lives. The only statistically significant difference found was that adolescent females had a higher rate of suicidal intention than males (χ2=15.72; df=3; p=0.043). No statistically significant differences were observed in age.

Frequency of self-destructive behaviour.

| Suicidal ideation | Suicidal planning | Suicidal gestures | Suicidal attempts | Self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Life prevalence | 55 | 20.6 | 6 | 2.2 | 25 | 9.4 | 12 | 4.5 | 58 | 21.7 |

| Alcohol/other drugs | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Males | 26 | 47.3 | 1 | 16.7 | 18 | 72 | 2 | 16.7 | 36 | 62.1 |

| Females | 29 | 52.7 | 5 | 83.3 | 7 | 28 | 10 | 83.3 | 22 | 37.9 |

| χ2 (gl; p) | 12.96 (3; 0.164) | 8.38 (3; 0.212) | 1.14 (3; 0.980) | 15.72 (3; 0.043) | 1.86 (3; 0.932) | |||||

| Age | ||||||||||

| 11–12 | 8 | 14.8 | 1 | 16.7 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 8.3 | 10 | 17.2 |

| 13–14 | 14 | 25.9 | 1 | 16.7 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 8.3 | 13 | 22.4 |

| 15–16 | 19 | 35.2 | 4 | 66.7 | 12 | 48 | 8 | 66.7 | 22 | 37.9 |

| 17 | 13 | 24.1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 28.6 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 22.4 |

| χ2 (gl; p) | 15.93 (5; 0.068) | 3.93 (5; 0.686) | 8.647 (5; 0.194) | 10.9 (5; 0.283) | 9.29 (5; 0.158) | |||||

χ2: Square Chi.

Bold: p<0.05.

In total, 47.6% of the adolescents studied reported to have had at least one of the SDBs studied throughout their lives, and nearly half (47.2%) of them scored positive in 2 or more SDBs. The most prevalent comorbidities were suicidal ideation and self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention, occurring in 10.1% of the adolescents; that is to say, 46.5% of those that suffered self-inflicted lesions also experienced suicidal ideation. All the adolescents that had attempted to commit suicide (4.5%) also reported suicidal ideation, and half of them reported self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention. The comorbid prevalence of suicidal gestures and self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention was 5.2 compared to 1.1% for suicidal gestures and suicidal attempts; that is to say, of all the adolescents that had suicidal gestures, 12% tried to commit suicide compared to 56% who suffered self-inflicted lesions.

Only 3 patients reported having consumed alcohol and other substances during the SDB stage. No significant clinical differences were observed except for a lower number of suicidal ideation, suicidal gestures and suicidal attempts episodes among those subjects that consumed toxic agents during such behaviours, compared to the episodes mean found in our study.

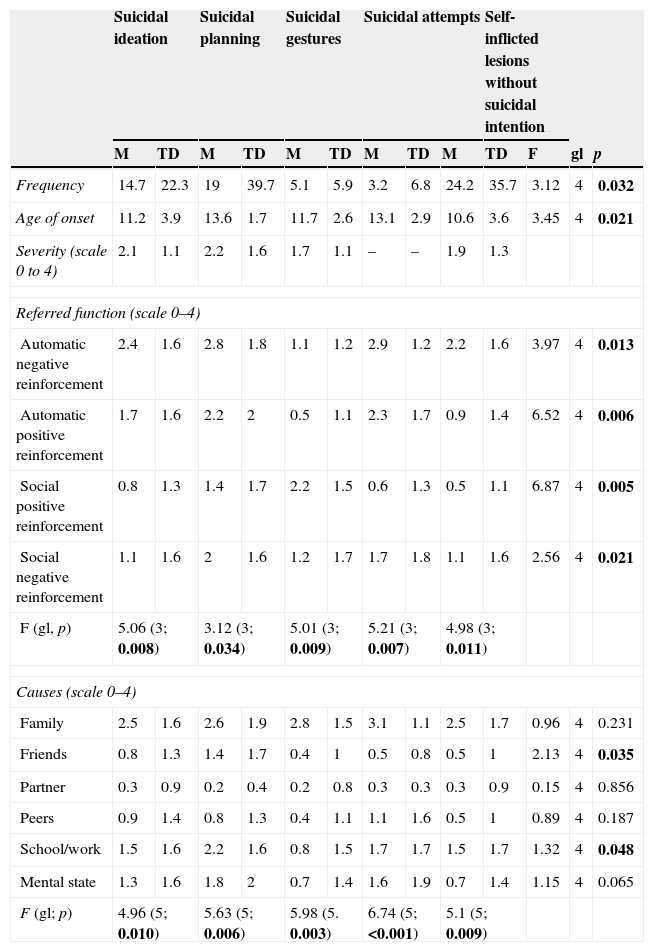

As shown in Table 5, non-suicidal self-inflicted lesions was the behaviour most frequently reported by adolescents with a mean of 24.2 episodes, compared to suicidal attempts that were the least frequent ones, with a mean of 3.2 episodes. The mean age range of SDB initiation varies from 10.6 years old (in the case of self-inflicted lesions) to 13.6 years old (in the case of suicidal planning). The mean age for the first suicidal attempt was 13 (2.9) years old.

Functions and triggering factors of self-destructive behaviour.

| Suicidal ideation | Suicidal planning | Suicidal gestures | Suicidal attempts | Self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | TD | M | TD | M | TD | M | TD | M | TD | F | gl | p | |

| Frequency | 14.7 | 22.3 | 19 | 39.7 | 5.1 | 5.9 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 24.2 | 35.7 | 3.12 | 4 | 0.032 |

| Age of onset | 11.2 | 3.9 | 13.6 | 1.7 | 11.7 | 2.6 | 13.1 | 2.9 | 10.6 | 3.6 | 3.45 | 4 | 0.021 |

| Severity (scale 0 to 4) | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.1 | – | – | 1.9 | 1.3 | |||

| Referred function (scale 0–4) | |||||||||||||

| Automatic negative reinforcement | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 3.97 | 4 | 0.013 |

| Automatic positive reinforcement | 1.7 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 2 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 6.52 | 4 | 0.006 |

| Social positive reinforcement | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 6.87 | 4 | 0.005 |

| Social negative reinforcement | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 2.56 | 4 | 0.021 |

| F (gl, p) | 5.06 (3; 0.008) | 3.12 (3; 0.034) | 5.01 (3; 0.009) | 5.21 (3; 0.007) | 4.98 (3; 0.011) | ||||||||

| Causes (scale 0–4) | |||||||||||||

| Family | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.6 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 1.5 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 0.96 | 4 | 0.231 |

| Friends | 0.8 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1 | 2.13 | 4 | 0.035 |

| Partner | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.15 | 4 | 0.856 |

| Peers | 0.9 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.89 | 4 | 0.187 |

| School/work | 1.5 | 1.6 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.32 | 4 | 0.048 |

| Mental state | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.15 | 4 | 0.065 |

| F (gl; p) | 4.96 (5; 0.010) | 5.63 (5; 0.006) | 5.98 (5. 0.003) | 6.74 (5; <0.001) | 5.1 (5; 0.009) | ||||||||

Bold: p<0.05.

Regarding the functions referred for the different SDBs, automatic negative reinforcement was the most intensely valued one for suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, suicidal attempts and self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention; that is to say, adolescents adopted these behaviours to try to “stop the bad feelings”. In opposition, the most important function attributed to suicidal gestures was social positive reinforcement, i.e., adolescents reported that suicidal gestures were used to “communicate something to someone or get their attention”.

Finally, regarding SDBs causes, family problems were the most intensely reported triggering factor, followed by problems at school/work and an altered mental state for suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, suicidal gestures and suicidal attempts.

DiscussionWe have come across some relevant findings in our study. The life prevalence found for suicidal attempts was 4.5% and around 20% for suicidal ideation, and these data are consistent with previous European and North American literature. In a systematic review of studies published between 1997 and 2007 about the epidemiology of suicide of Nock et al.,17 it was found that the prevalence of suicidal attempts in adolescents from the general population, aged between 12 and 17 years old, ranged between 1.5% and 12.1%; and 21.7–37.9% in the case of suicidal ideation. In some studies carried out in the USA, the authors discovered that the life prevalence of suicidal attempts ranged between 3.1% and 8.8% and between 19.8% and 24% for suicidal ideation. Our results are also consistent with the studies performed in Europe, such as those carried out in Italy and Portugal.23 However, juvenile suicides are relatively rare in Spain compared to other European countries such as Finland and Norway, where the rates are up to 5 times higher.24

Regarding behaviour without suicidal intention, nearly 22% of the patients reported self-inflicted lesions at least once in their lives. This finding is consistent with Jacobson and Gould's5 research that reviewed epidemiologic studies and studies on the phenomenology of adolescents’ self-inflicted lesions, having found a life prevalence that ranged between 13% and 23.2%. In a recent review of 53 studies published between 2005 and 2011 about self-inflicted lesions in adolescents from the general population, a mean prevalence rate of 18% throughout life was reported.

When comparing our results with the study of Kirchner et al.25 (one of the few studies about SDBs in adolescents in our country), we observed higher figures in our sample; the percentage of adolescents that had suffered self-injuring behaviour in their study was 11.4% versus 21.7% in ours, and 12.5% for suicidal ideation versus 20.6%. This difference could be based on the fact that our study has been carried out with a clinical population, compared to the school population studied in theirs.

Regarding the consumption of alcohol and other substances, it is surprising to see the low proportion of patients compared to previous studies.26–28 It is possible that the figures in our study are under-detected due to the social desirability bias, given the clinical context in which adolescents were assessed, unlike the general population studies, where the participants can remain anonymous. This supposes a study limitation in the relation between SDBs and substance consumption.

When analysing the comorbidities of the different SDBs, we found that suicidal ideation was present in all those adolescents who had tried to commit suicide, which made this piece of data consistent with previous results.29 An American prospective study determined that the presence of suicidal ideation at 15 years old increased around 12 times the risk of trying to commit suicide at 30 years old.30 On the other hand, half of the adolescents with suicidal attempts referred a history of self-inflicted lesions. Despite the fact that given the cross-sectional nature of our study we cannot clarify the type of relation between said types of behaviour, previous studies have considered non-suicidal self-inflicted lesions as an independent predictor of suicidal attempts.24

Regarding the functions reported for each SDB, our results are consistent with those reported by Nock et al.12 The most important function reported by adolescents was automatic negative reinforcement (i.e., “to stop or keep bad feelings away”), which suggests that the different SDBs can have a similar function. As Nock et al.31 proved, the only deviation from this pattern were suicidal gestures, as adolescents claimed to have used this behaviour to receive the effects of social reinforcement (i.e., “to communicate with someone and/or get their attention”). These results are also consistent with the definition of suicidal gestures (“self-injuring behaviour with no intention of dying, but rather pretending to commit suicide as a way of communicating with others”)18 as with our previous study about SDBs in adults.16 Thus, unlike other SDBs, it seems that adolescents with suicidal gestures could use this behaviour to have an influence on others, rather than to regulate their emotions. The data found about the low comorbidity of suicidal attempts among those who had suicidal gestures seem to point into the same direction.

It is also interesting to highlight that automatic negative reinforcement was the function most frequently attributed to self-inflicted lesions without suicidal intention. This finding is consistent with previous literature. Many authors have found that self-inflicted lesions persist mainly due to negative reinforcement.13,32–34 Despite their long-term negative consequences, self-inflicted lesions indeed stop undesired emotional states.32,35 In this sense, our results are in line with those of the authors who support the affection regulation function, such as Klonsky.36

However, it should be noted that other authors have found that self-inflicted lesions were associated to a social positive reinforcement function, particularly in the cases of social transmission. As pointed out by Nock and Prinstein,13 some adolescents may believe that their friends were able to achieve their interpersonal objectives by self-injury. These social influences have been described in literature,37,38 and the need to explore them more thoroughly has been also suggested.

As adolescents that try to commit suicide and/or self-inflict lesions upon themselves inform that they do it to get away from negative experiences, our results are consistent with the studies that suggest a functional equivalence between these two forms of self-injuring behaviour.13,39,40 Other studies show that self-inflicted lesions and suicidal attempts have differentiating functions and characteristics, although they could be considered as “different but equivalent”.41

Thus, considering the comorbidity between the different SDBs and the indicated transition from some type of behaviour to another, it is essential to assess them in a systematic and routine way. Instruments such as the structured interview employed (Escala de Pensamientos y Conductas Autolesivas [SITBI])16 are very useful tools not only in the topographic definition but also in the function definition of a wide range of SDBs that allow the obtainment of key information to guide the clinical intervention.

Finally, these results shall be interpreted in the context of limitations of this study. Due to the retrospective nature of the data, a possible limitation would be the memory bias. In this sense, it would be ideal to particularly test which factors predict the transition of thoughts from self-destructiveness to self-destructive behaviour, as it is vital to identify those individuals with the greatest risk so as to have the intervention done adequately. Although other studies have shown that some factors such as perinatal and prenatal complications could suppose a distal risk of suicidal behaviour,42,43 our study does not allow us to establish whether this happens more frequently than in the normal population, because a control group is missing to make comparisons. We are currently carrying out a prospective longitudinal study that includes a 6-month follow-up to determine the occurrence of new SDBs. Investigations shall continue to determine those factors that will help us predict the transition from some SDBs to others.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of persons and animalsThe authors state that no experiments were performed on human beings or animals as part of this investigation.

Data confidentialityThe authors state that they have followed the protocols of their workplace about the data publication of patients and that all the patients included in the study have received enough information and have given their written informed consent to participate in that study.

Right to privacy and informed consentAuthors have obtained the informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is in possession of the corresponding author.

FundingThe study has been funded by the 1st Research Scholarship of the Asociación Española de Psiquiatría del Niño y del Adolescente (Spanish Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Lucía Albarracín and Paloma Aroca for their research assistance.

Please cite this article as: Díaz de Neira M, García-Nieto R, de León-Martinez V, Pérez Fominaya M, Baca-García E, Carballo JJ. Prevalencia y funciones de los pensamientos y conductas autoagresivas en una muestra de adolescentes evaluados en consultas externas de salud mental. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2015;8:137–145.