The stigma against people with mental illness is very high. In Spain there are currently no tools to assess this construct. The aim of this study was to validate the Spanish version of the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness questionnaire in an adolescent population, and determining its internal consistency and temporal stability. Another analysis by gender will be also performed.

Material and methodsA translation and back-translation of the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness was performed. A total of 150 students of between 14 and 18 years old were evaluated with this tool in two stages. Internal consistency was tested using Cronbach α; and intraclass correlation coefficient was used for test–retest reliability. Gender-stratified analyses were also performed.

ResultsThe Cronbach α was 0.861 for the first evaluation and 0.909 for the second evaluation. The values of the intraclass correlation coefficient ranged from 0.775 to 0.339 in the item by item analysis, and between 0.88 and 0.81 in the subscales. In the segmentation by gender, it was found that girls scored between 0.797 and 0.863 in the intraclass correlation coefficient, and boys scored between 0.889 and 0.774.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness is a reliable tool for the assessment of social stigma. Although reliable results have been found for boys and girls, our results found some gender differences in the analysis.

El estigma hacia las personas con una enfermedad mental es muy elevado. En España no existen instrumentos actuales para evaluar este constructo. El objetivo del presente estudio es validar la versión española del cuestionario Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness en una población de adolescentes, estudiando la consistencia interna del instrumento, así como la estabilidad temporal. Este último análisis se realizará también por género.

Material y métodosSe llevó a cabo una traducción y retrotraducción del Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness. Se evaluaron con este instrumento un total de 150 alumnos de Enseñanza Secundaria Obligatoria, de entre 14 y 18 años, en 2 momentos. Se analizó la consistencia interna del instrumento mediante el α de Cronbach, y la fiabilidad test-retest con el coeficiente de correlación intraclase. Se realizaron análisis estratificados por género.

ResultadosEl α de Cronbach fue de 0,861 para la primera evaluación y de 0,909 para la segunda evaluación. Los valores del coeficiente de correlación intraclase oscilan entre 0,775-0,339 en el análisis de ítem por ítem, y entre 0,88-0,81 en las subescalas. En la segmentación por género encontramos que las puntuaciones en el coeficiente de correlación intraclase en el grupo de chicas está entre 0,797-0,863 y en los chicos entre 0,889-0,774.

ConclusionesEn conclusión podemos afirmar que el Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness es un instrumento fiable para la evaluación del estigma social. A pesar de resultar fiable de la misma manera para chicos y para chicas, se han encontrado algunas diferencias en el análisis por género.

Social stigma is a construct that includes negative attitudes, feelings, beliefs and behaviour towards a collective of individuals.1 Social stigma against people with mental illness has been reported widely, and is they are one of the collectives that experience the most stigma and social rejection.2 One of the aspects that favours negative attitudes against the mentally ill stems from the belief that they are aggressive and uncontrollable individuals.3

With the commencement of community-based psychiatry and with the need to integrate people with severe mental disorders into the community, it becomes even more important to assess the social stigma against mental illnesses in it. This attitude makes a specific characteristic of a person generalised to his or her entire identity; this in turn establishes a stereotypical classification that leads to discriminatory responses and becomes an obstacle for satisfactory evolution of the individual that suffers from the disease.4 Social stigma has been observed to be an element that lowers the quality of life and self-esteem and increases the possibility of depression in the mentally ill; and this affects their individual identity and interpersonal relationships.5,6 In addition, it can have social and legal repercussions such as the loss of liberty and of the rights to opportunity.7

In this context, intervention programmes to reduce social stigma take on special interest and can improve the integration of individuals with a mental illness in the community. Various interventions have been carried out in the general population to reduce social stigma, with satisfactory results. Some of these studies have focused on adolescents, given that they are one of the collectives most interested in and vulnerable to change; the results have been encouraging.8–12

Another point is that social stigma against mental illness is different according to sex. In previous studies on adolescents, we have found that boys have more stigmatising behaviours than girls, especially in the items that are most related to authoritarianism.12,13 In agreement with these studies, Ewalds-Kvist et al. (2013)14 suggest that women are more positive and open to the integration of the mentally ill, but that they also show more behaviours of fear and avoidance.

In this context, one of the biggest problems we have in the Spanish community lies in assessing social stigma. At present, there is only 1 scale validated in Spanish that makes it possible to evaluate social stigma in the general population: the Opinions about Mental Illness scale.15 However, this scale was developed in the 60s and, currently, the concept about mental health has been modified significantly. Besides, it is not comparable to other international studies.16 This is because it is practically unused. Internationally, the scale most often used to evaluate social stigma towards individuals with people with mental illness in the community is the Community Attitudes Toward the Mentally Ill (CAMI) from Taylor and Dear (1981).17 This scale is a briefer, revised and updated version of the Opinions about Mental Illness scale. The psychometric properties of the instrument showed high internal consistency in 4 factors: authoritarianism (α=0.68), benevolence (α=0.76), social restrictiveness (α=0.80) and mental health ideology in the community (α=0.88).17 Originally, this questionnaire was developed in the 1980s to predict and explain the reactions of the general population towards local services that took care of the needs of individuals with severe mental illness.

This scale is validated in various languages such as Finnish, Lithuanian, Italian, Swedish, Portuguese, Greek and Thai, besides English in its original version.18–22 For example, the validation study in Sweden, carried out by Högberg et al. (2008)19 using a group of nursing students, showed high values of internal consistency (α=0.90) and stability over time. In the case of the validation in Greek, Cronbach's α ranged from about 0.64 to 0.78 for the subscales.20

The CAMI has also been used to evaluate social stigma in various populations: nursing, psychiatry, relatives and priests/ministers, in addition to in the general population.21,23–28

The objective of our study was to validate the CAMI community social stigma scale using an adolescent. The internal consistency of the instrument was assessed, as well as its reliability over time. As a secondary objective, the reliability over time was assessed taking sex into consideration.

Material and methodsSubjectsA total of 150 elementary school students aged between 14 and 18 years old were interviewed twice, with a 1-week difference between the first assessment and the second. No type of specific intervention was given in the week between the 2 assessments. The schools that were involved in the study were participating in the Escola Amiga de Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu project, so this was a non-random, convenience sample. The schools were located in the vicinity of Barcelona (Spain).

AssessmentTo assess social stigma, the scale was translated and adapted. A process of English to Spanish translation, adaptation and back-translation was performed by an individual whose mother tongue was Spanish, and the inverse for the back-translation process (Spanish to English). The final instrument is available at: http://cibersam.es/cibersam/Plataformas/Plataformas+de+Investigaci%C3%B3n/Banco+de+Instruments.

CAMI from Taylor and Dear (1981).17 This is a 40-item scale evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale, which goes from completely agree to completely disagree. The scale consists of 4 factors called authoritarianism, benevolence, social restrictiveness and mental health ideology in the community. Each factor contains 10 statements referring to opinions about the way to treat and take care of individuals with a severe mental illness grave. Five of the 10 items are expressed positively, while the other 5 are written negatively. The score for each subscale is the sum of the positive items minus the negative ones. The authoritarianism subscale assesses the mentally ill as a class of individuals inferior to healthy people. The benevolence subscale evaluates accepting attitudes towards patients with mental problems, but the statements can result in a paternalistic attitude. The social restrictiveness subscale assesses the danger for society from the mentally ill and suggests that individuals with mental illness should be limited, both before and after hospitalisation. Lastly, the subscale for mental health ideology in the community assesses the attitudes and beliefs related to inserting people with mental illness in the community and in society in general.

Various, sociodemographic variables were recorded for the students, such as sex, age and whether they knew anyone with mental illness.

ProcedureThe students were told that survey was completely anonymous, but that they should choose a pseudonym to use so the 2 assessments could be matched. The project participants, as well as their relatives through the teachers, were informed and were requested to give their consent.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were performed using frequencies, means and standard deviation. Cronbach's α was used to assess the internal consistency of the instrument in the 2 assessments. The intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated to evaluate the stability of the items and subscales over time. In addition, for the subscales, this coefficient was calculated differentiated by sex. We used the scoring proposed by Landis and Koch (1977)29: a score of 0.4–0.6 indicates moderate agreement; 0.6–0.8 indicates strong agreement; and 0.8–1.0 indicates perfect agreement. SPSS version 22 was used for the statistical analysis.

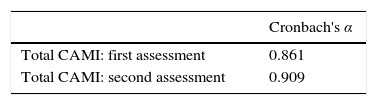

ResultsA total of 150 students responded to the instrument in 2 different times in the study; 73 were boys and 77, girls. The mean age of the sample total was 15.23 years (standard deviation [SD]=0.787). Divided by sex, the mean age of the boys was 15.25 (SD=0.760) and of the girls, 15.21 (SD=0.817). No statistically significant differences in age were found based on sex. Of the students in the sample, 90 (60%) knew individuals that had a mental illness. Cronbach's α was calculated for the CAMI items in both times of assessment. These figures are 0.861 for the first assessment and 0.909 for the second assessment (Table 1).

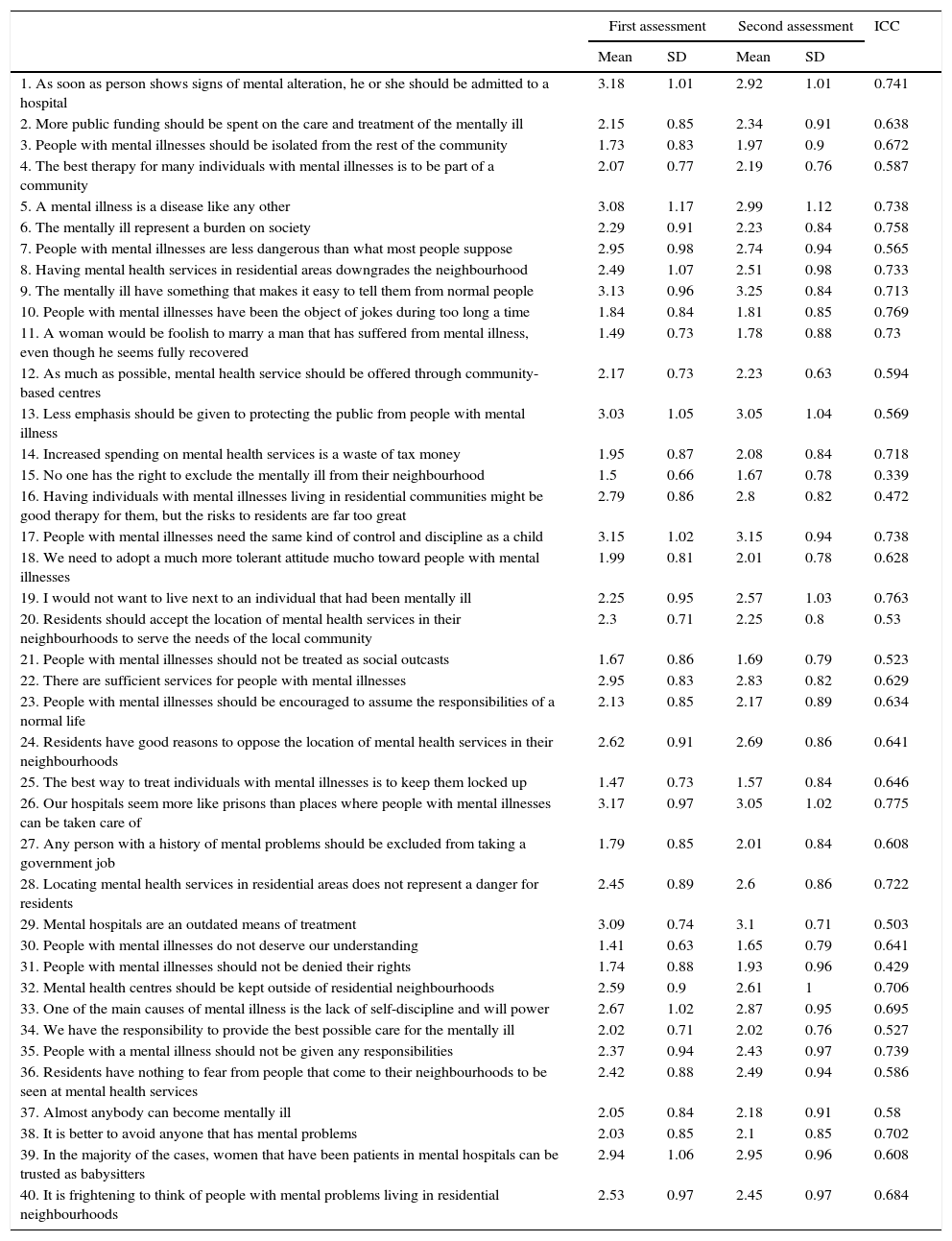

Table 2 indicates the mean for each of the items at the 2 assessment times and the intraclass correlation coefficient between the 2 evaluations. The intraclass correlation coefficient values range from 0.75 (Item 26) to 0.339 (Item 15) and only 3 values are lower than 0.50.

Mean scores for each item and intraclass correlation coefficient between the 2 assessments per item.

| First assessment | Second assessment | ICC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| 1. As soon as person shows signs of mental alteration, he or she should be admitted to a hospital | 3.18 | 1.01 | 2.92 | 1.01 | 0.741 |

| 2. More public funding should be spent on the care and treatment of the mentally ill | 2.15 | 0.85 | 2.34 | 0.91 | 0.638 |

| 3. People with mental illnesses should be isolated from the rest of the community | 1.73 | 0.83 | 1.97 | 0.9 | 0.672 |

| 4. The best therapy for many individuals with mental illnesses is to be part of a community | 2.07 | 0.77 | 2.19 | 0.76 | 0.587 |

| 5. A mental illness is a disease like any other | 3.08 | 1.17 | 2.99 | 1.12 | 0.738 |

| 6. The mentally ill represent a burden on society | 2.29 | 0.91 | 2.23 | 0.84 | 0.758 |

| 7. People with mental illnesses are less dangerous than what most people suppose | 2.95 | 0.98 | 2.74 | 0.94 | 0.565 |

| 8. Having mental health services in residential areas downgrades the neighbourhood | 2.49 | 1.07 | 2.51 | 0.98 | 0.733 |

| 9. The mentally ill have something that makes it easy to tell them from normal people | 3.13 | 0.96 | 3.25 | 0.84 | 0.713 |

| 10. People with mental illnesses have been the object of jokes during too long a time | 1.84 | 0.84 | 1.81 | 0.85 | 0.769 |

| 11. A woman would be foolish to marry a man that has suffered from mental illness, even though he seems fully recovered | 1.49 | 0.73 | 1.78 | 0.88 | 0.73 |

| 12. As much as possible, mental health service should be offered through community-based centres | 2.17 | 0.73 | 2.23 | 0.63 | 0.594 |

| 13. Less emphasis should be given to protecting the public from people with mental illness | 3.03 | 1.05 | 3.05 | 1.04 | 0.569 |

| 14. Increased spending on mental health services is a waste of tax money | 1.95 | 0.87 | 2.08 | 0.84 | 0.718 |

| 15. No one has the right to exclude the mentally ill from their neighbourhood | 1.5 | 0.66 | 1.67 | 0.78 | 0.339 |

| 16. Having individuals with mental illnesses living in residential communities might be good therapy for them, but the risks to residents are far too great | 2.79 | 0.86 | 2.8 | 0.82 | 0.472 |

| 17. People with mental illnesses need the same kind of control and discipline as a child | 3.15 | 1.02 | 3.15 | 0.94 | 0.738 |

| 18. We need to adopt a much more tolerant attitude mucho toward people with mental illnesses | 1.99 | 0.81 | 2.01 | 0.78 | 0.628 |

| 19. I would not want to live next to an individual that had been mentally ill | 2.25 | 0.95 | 2.57 | 1.03 | 0.763 |

| 20. Residents should accept the location of mental health services in their neighbourhoods to serve the needs of the local community | 2.3 | 0.71 | 2.25 | 0.8 | 0.53 |

| 21. People with mental illnesses should not be treated as social outcasts | 1.67 | 0.86 | 1.69 | 0.79 | 0.523 |

| 22. There are sufficient services for people with mental illnesses | 2.95 | 0.83 | 2.83 | 0.82 | 0.629 |

| 23. People with mental illnesses should be encouraged to assume the responsibilities of a normal life | 2.13 | 0.85 | 2.17 | 0.89 | 0.634 |

| 24. Residents have good reasons to oppose the location of mental health services in their neighbourhoods | 2.62 | 0.91 | 2.69 | 0.86 | 0.641 |

| 25. The best way to treat individuals with mental illnesses is to keep them locked up | 1.47 | 0.73 | 1.57 | 0.84 | 0.646 |

| 26. Our hospitals seem more like prisons than places where people with mental illnesses can be taken care of | 3.17 | 0.97 | 3.05 | 1.02 | 0.775 |

| 27. Any person with a history of mental problems should be excluded from taking a government job | 1.79 | 0.85 | 2.01 | 0.84 | 0.608 |

| 28. Locating mental health services in residential areas does not represent a danger for residents | 2.45 | 0.89 | 2.6 | 0.86 | 0.722 |

| 29. Mental hospitals are an outdated means of treatment | 3.09 | 0.74 | 3.1 | 0.71 | 0.503 |

| 30. People with mental illnesses do not deserve our understanding | 1.41 | 0.63 | 1.65 | 0.79 | 0.641 |

| 31. People with mental illnesses should not be denied their rights | 1.74 | 0.88 | 1.93 | 0.96 | 0.429 |

| 32. Mental health centres should be kept outside of residential neighbourhoods | 2.59 | 0.9 | 2.61 | 1 | 0.706 |

| 33. One of the main causes of mental illness is the lack of self-discipline and will power | 2.67 | 1.02 | 2.87 | 0.95 | 0.695 |

| 34. We have the responsibility to provide the best possible care for the mentally ill | 2.02 | 0.71 | 2.02 | 0.76 | 0.527 |

| 35. People with a mental illness should not be given any responsibilities | 2.37 | 0.94 | 2.43 | 0.97 | 0.739 |

| 36. Residents have nothing to fear from people that come to their neighbourhoods to be seen at mental health services | 2.42 | 0.88 | 2.49 | 0.94 | 0.586 |

| 37. Almost anybody can become mentally ill | 2.05 | 0.84 | 2.18 | 0.91 | 0.58 |

| 38. It is better to avoid anyone that has mental problems | 2.03 | 0.85 | 2.1 | 0.85 | 0.702 |

| 39. In the majority of the cases, women that have been patients in mental hospitals can be trusted as babysitters | 2.94 | 1.06 | 2.95 | 0.96 | 0.608 |

| 40. It is frightening to think of people with mental problems living in residential neighbourhoods | 2.53 | 0.97 | 2.45 | 0.97 | 0.684 |

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; SD, standard deviation.

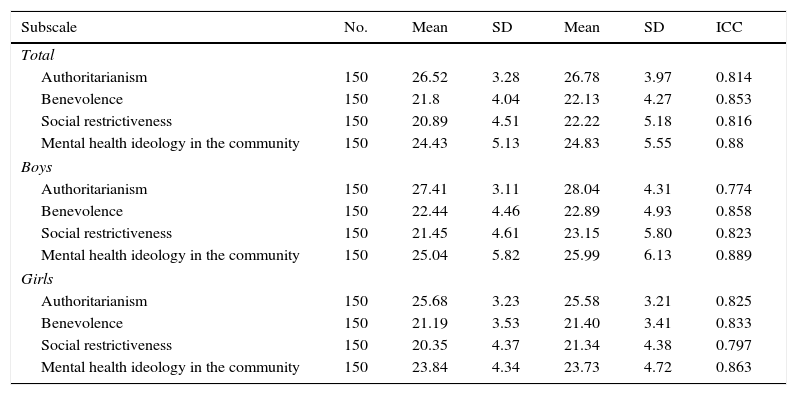

Table 3 shows the intraclass correlation coefficients for each of the subscales, the sample total and the sample segmented by sex. The scores for intraclass correlation coefficients in each of the subscales for the sample total are above 0.80. Differentiation by sex also gives us values above 0.80, except for authoritarianism for boys (0.774) and social restrictiveness for girls (0.797).

Mean scores for each subscale and intraclass correlation coefficient between the 2 assessments for the entire sample and by sex.

| Subscale | No. | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||||

| Authoritarianism | 150 | 26.52 | 3.28 | 26.78 | 3.97 | 0.814 |

| Benevolence | 150 | 21.8 | 4.04 | 22.13 | 4.27 | 0.853 |

| Social restrictiveness | 150 | 20.89 | 4.51 | 22.22 | 5.18 | 0.816 |

| Mental health ideology in the community | 150 | 24.43 | 5.13 | 24.83 | 5.55 | 0.88 |

| Boys | ||||||

| Authoritarianism | 150 | 27.41 | 3.11 | 28.04 | 4.31 | 0.774 |

| Benevolence | 150 | 22.44 | 4.46 | 22.89 | 4.93 | 0.858 |

| Social restrictiveness | 150 | 21.45 | 4.61 | 23.15 | 5.80 | 0.823 |

| Mental health ideology in the community | 150 | 25.04 | 5.82 | 25.99 | 6.13 | 0.889 |

| Girls | ||||||

| Authoritarianism | 150 | 25.68 | 3.23 | 25.58 | 3.21 | 0.825 |

| Benevolence | 150 | 21.19 | 3.53 | 21.40 | 3.41 | 0.833 |

| Social restrictiveness | 150 | 20.35 | 4.37 | 21.34 | 4.38 | 0.797 |

| Mental health ideology in the community | 150 | 23.84 | 4.34 | 23.73 | 4.72 | 0.863 |

ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; SD, standard deviation.

Our results show that the Spanish version of the CAMI questionnaire is reliable.

The CAMI is shown to be a comprehensible instrument for the adolescents that have participated in the study. Consequently, it can be a useful instrument for evaluating social stigma towards people with a severe mental disorder.

The high scores in Cronbach's α indicate that the instrument is consistent, being homogeneous in the evaluation that the adolescents make of the construct of social stigma towards the mentally ill. These data coincide with those found by Högberg et al. (2008)19 in Sweden, and even present values higher than those of the validation of the original instrument17 and those found in Greece.20 These studies were validated using the general population; none of them was carried out with adolescents. This indicates that the results for this population may be equally valid as those found in the general population.

The CAMI is an instrument that is stable over time. Almost all the items present scores for the intraclass correlation coefficient of approximately 0.6–0.7 between the 2 times of assessment. Consequently, these items are stable, as Landis and Koch29 suggest. Only 3 items have scores under 0.5 in relation to the stability over time of the instrument: “No one has the right to exclude the mentally ill from their neighbourhood” (Item 15), “People with mental illnesses should not be denied their rights” (Item 31) and “Having individuals with mental illnesses living in residential communities might be good therapy for them, but the risks to residents are far too great” (Item 16). The first 2 of these are statements with a double negation [in Spanish], which might make their interpretation more difficult. As for the third item, it has 2 parts of content, which might also make the interpretation focus on 1 of the 2 messages at different times. In future studies, the fact that these items might not be totally representative should be considered. Only 1 previous study has evaluated the stability over time of the instrument, showing values similar to those found in our study.19

Turning to the subscales, it can be seen that they remain stable through the 2 assessments, both when the total sample is analysed, and when the sample is segmented by sex. In the case of the analysis by sex, the authoritarianism subscale presents less stability for boys, while the same thing happens in the social restrictiveness subscale for girls. In spite of this, the values found are high. Previous studies already suggested gender differences in the conception of social stigma,12–14 and this might mark the differences with respect to the stability of these subscales.

In the study by Evans-Lacko et al. (2014),30 Spain is shown to be a country in which little research about the social stigma of mental illness is carried out. One of the barriers might be that there are no instruments validated in our context that are comparable to those used in other countries. The fact that a validated Spanish version of the CAMI is available will help to make it possible to continue research in this matter at the national level. It will also allow us to compare with other studies at the international level.

Future studies should evaluate the validity and reliability of the instrument in other populations, given that one of the limitations of our study is that the validation is carried out using a sample of adolescents. Even though the results found are fairly similar to those of other studies, it would be of interest to evaluate whether the instrument behaves in the same way using other populations. Another point is that the instrument had previously been validated in other countries using an adult population; consequently, in spite of our favourable reliability results, it cannot be guaranteed that it is valid for the adolescent population. Another limitation of the study is that reliability over time was carried out with a 1-week time period. In further studies, longer time periods should be considered.

In short, we can state that the CAMI is a reliable instrument in its Spanish version. This study is useful for several reasons. The first is that it allows us to have the validation in Spanish available for an instrument needed to understand more about what the community thinks about people with severe mental disorders. In second place, it will make it possible to carry out descriptive population studies on social stigma towards the mentally ill. And, in third place, this understanding of the situation will help to perform appropriate interventions to reduce the social stigma that exists in the community towards people with severe mental disorders, in a more targeted fashion.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We express our thanks to the schools in the programme Escola Amiga de la Obra Social Sant Joan de Déu (especially Escola Frederic Mistral, Escola Avenç, Escola Garbí, Escola Sant Josep), to the Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu and CIBERSAM [Spanish virtual mental health research centre] for their participation.

Both authors should be considered as first authors.

Please cite this article as: Ochoa S, Martínez-Zambrano F, Vila-Badia R, Arenas O, Casas-Anguera E, García-Morales E, et al. Validación al castellano de la escala de estigma social: Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness en población adolescente. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc.). 2016;9:150–157.