Despite the consensus achieved in the homogenisation of clinical criteria by categorical psychiatric classification systems (DEM and CIE), they are criticised for a lack of validity and inability to guide clinical treatment and research. In this review article we introduce the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) framework as an alternative framework for translational research in psychiatry.

The RDOC framework systematises both research targets and methodology for research in psychiatry. RDoC is based on a catalogue of neurobiological and neurocognitive evidence of behaviour, and conceives psychopathology as the phenotypic expression of alterations of functional domains that are classified into 5 psychobiological systems. The RdoC framework also proposes that domains must be validated with evidence in 7 levels of analysis: genes, molecules, cells, nerve circuits, physiology, behaviour and self-reports. As opposed to categorical systems focused on diagnosis, RDoC focuses on the study of psychopathology as a correlate of detectable functional, biological and behavioural disruption of normal processes.

In order to build a useful psychiatric nosology for guiding clinical interventions, the RDoC research framework links the neurobiological basis of mental processes with phenotypical manifestations. Although the RDoC findings have not yet been articulated into a specific model for guiding clinical practice, they provide a useful transition system for creating clinical, basic and epidemiological research hypotheses.

Pese al éxito (o consenso) conseguido en la homogeneización de criterios clínicos por los sistemas de clasificación psiquiátrica categoriales (DSM y CIE), su validez y utilidad, clínica y en investigación, son cuestionables. En este artículo de revisión presentamos el marco Criterios de Investigación por Dominios (Research Domain Criteria, RDoC) como una alternativa para la investigación traslacional en psiquiatría.

El marco de investigación traslacional RDoC sistematiza dianas y métodos de investigación en psiquiatría. RDoC parte de un catálogo de bases neurofuncionales de la conducta y plantea la psicopatología como la expresión fenotípica de las alteraciones en dichas funciones. Estas se clasifican en 5 sistemas psicobiológicos. Los constructos funcionales se validan mediante evidencia proveniente de estudios básicos en 7 niveles de análisis: genes, moléculas, células, circuitos nerviosos, fisiología, conducta y autoinformes. Frente a los sistemas categoriales centrados en el diagnóstico, RDoC propone centrar el estudio de la psicopatología como correlato de alteraciones funcionales detectables, biológicas y comportamentales.

RDoC es un marco de investigación que vincula el sustrato biológico con las manifestaciones fenotípicas, para llegar a una nosología psiquiátrica útil para guiar el tratamiento. Pese a que los hallazgos de RDoC no articulan un modelo concreto de guía para la práctica clínica, es un sistema de transición útil para crear hipótesis de investigación clínica, básica y epidemiológica.

In 2013, the publication of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)1 reopened the debate about the validity of diagnostic categories. The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in the United States disconnected its strategy and research priorities from the categorical diagnosis systems in its search for therapeutic targets to improve treatment results.2 To this end, the Research Domain Criteria Project (RDoC) was created with its ultimate aim to systematise evidence on mental illness for the enhancement of treatment results.

Despite the debate generated by this proposal of paradigm change,3,4 the RDoC programme has had little repercussion in the Spanish literature (see5,6). The aim of this article was to publicise the RDoC research framework in the Spanish literature.

The most extensive diagnostic classification systems of mental health are the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association (2013) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) of the World health Organisation (2011).7 Despite the success these systems have in criteria uniformity the extent to which the diagnoses are clinically useful for prognosis and treatment guidance is an issue continuously under debate in the mental health sector.8–10

Three main criticisms have been made regarding these classifying systems: (a) high comorbidity between diagnostic entities11,12; (b) diversity of clinical symptoms of patients with the same diagnosis13,14 and (c) low predictive capacity to treatment response.15 The backdrop of these criticisms was the almost exclusively descriptive nature of the classification systems,16 where the diagnostic entities were grouped together by consensus from experts regarding the similarity of symptoms. The methodology of these systems is based on the definition of disorders which involve characteristic symptoms as a diagnostic strategy from the symptom, without specifying the mechanisms of dysfunction that explain the symptoms. Thus, no specific pharmacological or psychotherapeutic treatment targets are provided,17 which often results in the treatment being a trial and error procedure.18

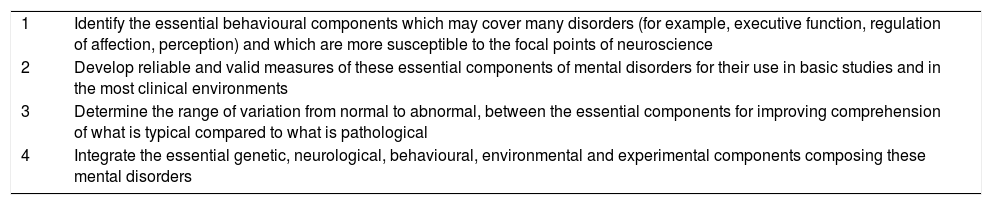

The research domain criteria programmeIn the light of these criticism and based on accumulated research from neuroscience and clinical evidence,19 the NIMH included objective 1.4 in its strategic plan, which was to “develop, for research purposes, new ways of classifying mental disorder based on dimensions of observable behaviour and neurobiological measures”.20 This general aim materialised in the specific objectives contained in Table 1, which focus on discovering mechanisms, developing measures and discovering the distribution of psychopathology in the general population.

Objectives defined by the NIMH for the development of new forms of classification of mental disorders based on the dimensions of observable behaviour and neurobiological measures.

| 1 | Identify the essential behavioural components which may cover many disorders (for example, executive function, regulation of affection, perception) and which are more susceptible to the focal points of neuroscience |

| 2 | Develop reliable and valid measures of these essential components of mental disorders for their use in basic studies and in the most clinical environments |

| 3 | Determine the range of variation from normal to abnormal, between the essential components for improving comprehension of what is typical compared to what is pathological |

| 4 | Integrate the essential genetic, neurological, behavioural, environmental and experimental components composing these mental disorders |

Source: Adapted from Cuthbert and Insel.19

The method was made operative in the RDoC programme, which proposed a medical precision focus aimed at improving the comprehension and treatment of mental illness.19

The background of the RDoC programme are the NIMH research frameworks developed in the programmes on Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (MATRICS)21 and Cognitive Neuroscience Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia (CNTRICS).22 These 2 programmes which arose from streamlining the pharmaceutical industry and basic research on research priorities in schizophrenia, are aimed at facilitating clinical trials in schizophrenia. To do this, the projects focus is on the study of indirect evaluation results (Surrogate endpoints; Marder and Fenton21): early markers, of non invasive, low cost measurement which allow for valid inference to be made regarding the result from an intervention.23 As a result, MATRICS and CNTRICS developed an evaluation system in schizophrenia based on neurocognitive tasks associated with biological dysfunctions. Thus the MATRICS measurements were created as strictly linked to functionality biomarkers, increasing the latter's validity and provided treatment targets specifically associated with behavioural manifestations. Biological, neuropsychological and psychiatric phenotype markers have been researched, related to both schizophrenia in general and to each of its dimensions.24 These biomarkers do not only show high sensitivity, extreme specificity and an appropriate predictive value, but they have to be validated in highly extensive samples, coming from very diverse population groups and obtained using extremely standardised processes.25

RDoC is currently not a diagnostic system. Neither does it purport to be so. RDoC does not provide labels or classifications, it provides a framework with which to organise cross-sectional research in psychiatry.3,14,20 The RDoC framework, based on the theory of applied systems to neuroscience,26 establishes a methodology to link methods and information sources to research targets. The specific proposal by RDoC is that research into psychopathology is directed towards the study of systems using different sources of evidence.27,28 These systems, which are dominions in RDoC terminology, are an inventory of functional systems which imply research targets. Psychopathology is regarded as a phenotype expression of alterations in these domains, and its components (from molecular to behavioural) are ultimately where clinical decisions are directed.28 The systems model does not imply biological determinism or reductionism. The idea is more that psychopathology occurs in the central nervous systems (CNS) and, therefore, its manifestations must also be detectable at that level.

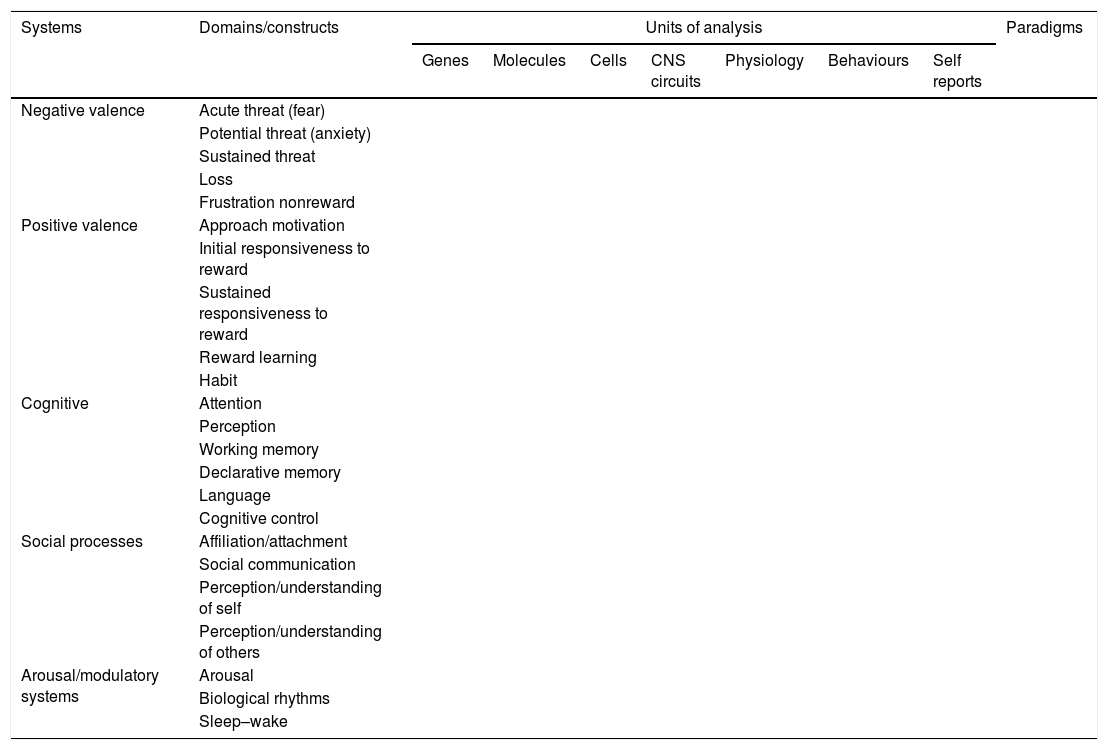

The RDoC matrixThe RDoC matrix is the proposal: a cross-sectional systematisation of domains (functional constructs) with analysis units (methodological study levels of its components).

Table 2 contains the RDoC matrix. The five major psychobiological domains relevant to psychopathology are presented in it. Located in the rows of the matrix are: (a) negative valence systems: responsible for the protective responses to aversive situations or contexts which include the responses of fear, anxiety, sustained threat, loss, frustration and withdrawal of reward; examples of symptom logy associated with this system could be high reaction to stress or problems of emotional deregulation; (b) positive valence systems: responsible for the response of approach to situations or contexts which are positively motivational that include motivation for approach, initial sensitivity and sustained sensitivity to reward, learning through enhancement and the creation of habits; examples of symptom logy associated with this system could be the loss of pleasure in everyday activities or loss of energy for productive tasks; (c) cognitive systems, responsible for processing information, including attention, perception, work memory, declarative memory, language and cognitive control; examples of symptom logy associated with this system could be problems with memory or executive functions; (d) social processes, responsible for measuring responses in interpersonal situations, including behaviours of affiliation and attachment, social communication, perception and comprehension of oneself and others; examples of symptomology associated with this system could be social withdrawal or insufficient socialisation and (e) arousal and modulatory systems, responsible for the arousal of neurological systems and homeostatic modulation, which include the constructs of arousal, biological rhythms and sleep–wake cycle; an example of symptomatic changes in this domain could include problems with sleep or problems with the regulating systems of excitement or arousal.

RDoC matrix.

| Systems | Domains/constructs | Units of analysis | Paradigms | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genes | Molecules | Cells | CNS circuits | Physiology | Behaviours | Self reports | |||

| Negative valence | Acute threat (fear) | ||||||||

| Potential threat (anxiety) | |||||||||

| Sustained threat | |||||||||

| Loss | |||||||||

| Frustration nonreward | |||||||||

| Positive valence | Approach motivation | ||||||||

| Initial responsiveness to reward | |||||||||

| Sustained responsiveness to reward | |||||||||

| Reward learning | |||||||||

| Habit | |||||||||

| Cognitive | Attention | ||||||||

| Perception | |||||||||

| Working memory | |||||||||

| Declarative memory | |||||||||

| Language | |||||||||

| Cognitive control | |||||||||

| Social processes | Affiliation/attachment | ||||||||

| Social communication | |||||||||

| Perception/understanding of self | |||||||||

| Perception/understanding of others | |||||||||

| Arousal/modulatory systems | Arousal | ||||||||

| Biological rhythms | |||||||||

| Sleep–wake | |||||||||

Source: Adapted from Cuthbert.3

In the columns, the RDoC matrix presents 7 study components from these systems: the units of analysis. Constructed from a micro to a more macro level, these range from genetic to behavioural, each one linked to a research strategy. At the most basic levels of genetic, molecular and cellular analysis, methodology are genomic and cellular research. The circuitry unit analysis of the CNS represents activity and response measures of the neuronal circuit, with methodology based on neuroimaging or electroencephalography techniques or tests validated as markers which replace the cerebral circuit functioning (for example, orientation response). The physiological units are measures of validated function, related to neuropsychological reactions, but they do not measure the activity of the circuit directly (for example, heart rate or level of cortisol in the blood). The behavioural units are focused on observable behaviour and methodology is characteristic of clinical investigation, using systematic registers (for example, recording of observed behaviour in a child), or the performing of tasks (for example, rights and wrongs in continuous execution tasks). Finally, self reports are registers based on the informed subjective experience of the patient, through interviews or questionnaires. This methodology is typical of more macro research, such as epidemiology. The additional column of paradigms in each study systemises the type of tasks, methods or designs which are used to respond to a research question in a certain system and analysis level. One major aspect of RDoC research is the insistence that in all types of research strategies different analysis units must cross over, so that they obtain concurrent evidence in different units on the same domain. Thus the same research design obtains data which validate the results of one analysis unit as the indicator of others.

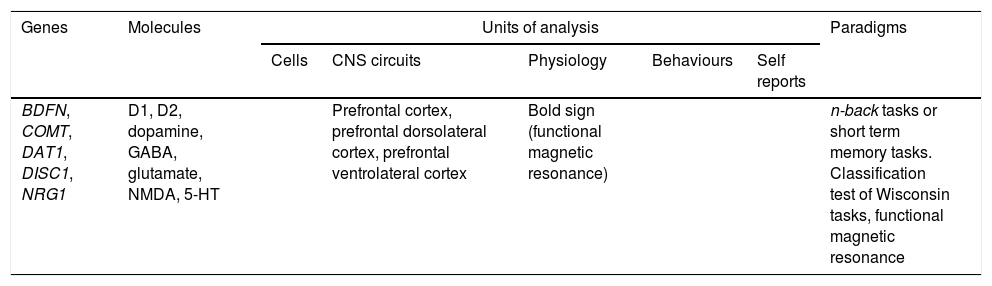

One example of the RDoC methodology is the genetic bases study of changes to the work memory in schizophrenia by Schwarz et al.29 In the RDoC framework, the system under investigation is the cognitive systems domain, specifically the work memory construct (see Table 3). For this, the genetic associations between work memory and its functional correlatives are reviewed. With regard to genetic level analysis units, the objectives focus on the expression of genes involved in the synthesis and degradation of dopamine (COMT, DAT1) and neuronal proliferation (BDFN, DISC1 and NRG1). On a molecular level neurotransmitters (GABA, 5-HT) are proposed as objectives of analysis, together with agonist molecules and dopamine antagonist nerve or glutamine receptors (D1, D2) (NMDA). In the CNS circuit unit we find neuronal structures involved in the development of executive functions (prefrontal cortex). Lastly, in the paradigm unit research is proposed through the use of functional magnetic resonance, the Wisconsin card classification test or short term memory tasks (n-back tasks).

Example of the RDoC methodology in changes in work memory in schizophrenia by Schwarz et al.29

| Genes | Molecules | Units of analysis | Paradigms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells | CNS circuits | Physiology | Behaviours | Self reports | |||

| BDFN, COMT, DAT1, DISC1, NRG1 | D1, D2, dopamine, GABA, glutamate, NMDA, 5-HT | Prefrontal cortex, prefrontal dorsolateral cortex, prefrontal ventrolateral cortex | Bold sign (functional magnetic resonance) | n-back tasks or short term memory tasks. Classification test of Wisconsin tasks, functional magnetic resonance | |||

Source: Generated from Swartz et al.49

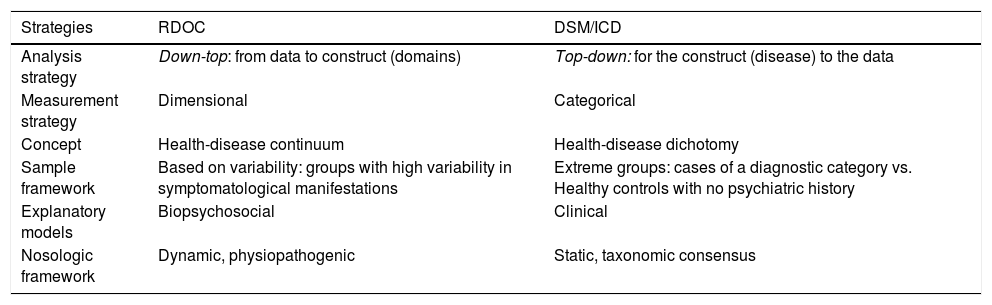

This conceptual framework involves a future RDoC nosologic classification system having major differences with the categorical system. Furthermore, there are different epistemic assumptions on mental disease from the RDoC. The main differences between RDoC and the DSM and ICD categorical classification systems are summarised in Table 4.

Distinctions between the RDoC strategy and the traditional DSM and ICD systems.

| Strategies | RDOC | DSM/ICD |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis strategy | Down-top: from data to construct (domains) | Top-down: for the construct (disease) to the data |

| Measurement strategy | Dimensional | Categorical |

| Concept | Health-disease continuum | Health-disease dichotomy |

| Sample framework | Based on variability: groups with high variability in symptomatological manifestations | Extreme groups: cases of a diagnostic category vs. Healthy controls with no psychiatric history |

| Explanatory models | Biopsychosocial | Clinical |

| Nosologic framework | Dynamic, physiopathogenic | Static, taxonomic consensus |

These differences are both conceptual and methodological. Firstly, RDoC follows a guided strategy by data (construct data). The analysis units serve as the starting point and the disorders are interruptions of normal functioning which are expressed as symptoms, resulting in the nosologic model having an explicitly physiopathogenic basis. In the categorical framework, the disorder is established from an observation of expert consensus on the symptoms which define one (from the data construct), with which the clinical representativeness of these symptoms is determined. However, physiopathology is sought from the nosologic entity and the diversity of symptom grouping may therefore threaten the search for specific mechanisms.

With regard to the concept of disease, the focus of RDoC is explicitly dimensional: it studies the complete range of health to disease variation. The health/disease continuum is interrupted by an alteration in the underlying mechanism, which has a normal function and varying disruptions. However, the system and mechanisms are common to all subjects and may be studied in all individuals. Against this, the categorical framework starts from the dichotomy of health/disease and is focused on the study of disease, using non-pathological subjects as comparison.

The RDoC framework examines the importance of endophenotypes, which could replace or at least complement the signs and symptoms of the DSM/ICD categorical systems. Endophenotypes are internal phenotypes observable through biochemical measurements, from imaging or lab tests.30 For its part, the DSM signs and symptoms would be “exophenotypes”. The concept of endophenotype is important within the RDoC framework for all of the following: it is assumed that they are closer to the genetic original and considering them could help to make identification more reliable of the genetic basis of mental disorders. They also have to be capable of providing more accurate and valid information on the biological systems of the disease (such as the positive and negative valence constructs).13 It has also been postulated that endophenotypes are, in general, independent from the state and therefore are identifiable even in the absence of clinical manifestations of the disorder.30 Finally, since many endophenotypes appear in different mental disorders they are consistent with the transdiagnostic focus of RDoC and its emphasis on the identification of the aetiological process of multiple DSM/ICD disorders.31

Examples of endophenotypes are those related to prepulse inhibition, work memory or eye-coordination function, among many others. They all comply with the requisites of being manifestations prior to symptoms and the consequences of genes or neuronal circuits, being biological markers with some genetic based evidence and internal phenotypes.30 The use of endophenotypes in RDoC has potential, although certain precautions have been noted in their analysis.13

This leads to different study strategies with regard to design. RDoC highlights the study in experimental strategies with individuals with different symptoms within an area of disuse and a control group of characteristics of varying gravity. The variability of health to disease would therefore be captured. However, in the categorical framework the standard design is based on sampling strategies or experimental assignation of individuals who fulfil the criteria of a certain diagnostic category and an “extremely normal” control group without any psychiatric history.

The RDoC model starts with an integrating, multidisciplinary model aimed at providing a structure which provides equal weight to the different levels of analysis.19 Involved in the study, therefore, are the following: genomic, physiological, neuroscientific, cognitive and clinical investigation. All of these provide evidence and foster hypothesis. Compared with this, in the categorical framework a clinically-based explanatory framework prevails, which establishes disease as a unit of analysis in which other methodologies of investigation are to be applied that presuppose a psychiatric entity as a specific disease.

It is important to highlight that, as a research framework, RDoC is different from a nosologic one, which is dynamic. In other words, both the domains and labels of disease are considered modifiable in accordance with new evidence on altered mechanisms. In contrast, the categorical system has a static nosologic framework which changes with new consensus, often redefining behaviours as pathologies. Since this framework is based on the definition of pathological behaviours and not mechanisms, there is a danger of pathologisation of daily life or over diagnosis.

Criticisms of the RDoC frameworkThe RDoC proposal has not been exempt from conceptual and methodological criticisms. The RDoC proposal has been accused of being too “open” as a clinical practice guide and it has been suggested that the matrix is provisional and open to review.32

One major criticism refers to the validity of the systems proposal and units of analysis of the RDoC matrix, as well as the significance and utility of the domains in clinical cases outside the area of research.27 The result capacity of the analysis units to guide clinical decisions has been questioned due to the difficulty of determining that somebody is a “case”. The omission in the RDoC matrix of any appreciation of the difference between health and ill has also been questioned, as has the lack of importance attached to the course of the diseases, with emphasis on treatment results, as this makes the process of taking clinical decisions more complex.27 As a result it has been proposed that it is essential for RDoC to design a set of provisional points of reference and strategies from which to be able to evaluate their progress and check their incremental validity (compared with DSM and ICD) in the theoretical prediction and of relevant external criteria. These criticisms show that it is essential to include in the RDoC assessment important clinical factors, such as natural history and treatment response.32 Although these aspects are not currently fully integrated in the RDoC matrix, under the provisionality of the RDoC there is an improvement philosophy based on evidence, which is always open to review. Moreover, RDoC is a strategic proposal rather than one of content, and therefore the accusation of provisionality or lack of clinical guide may not be fair. As a nosologic and aethiopathogenic research framework,3,14,20 and despite the fact the long-term objective is to provide a way in which research results may be translated into clinical decisions,28 at the moment RDoC's objective is to systematise the available evidence.

A second highly criticised aspect of the RDoC proposal is of professing a biological fundamentalism which excludes social or cultural influences33–36: this proposal has been accused of confusing biological mediation with biological aetiology.13 It has also been suggested that the closeness of RDoC with concepts such as endophenotype37 is a weakness of approximation, since there is scarce and inconsistent evidence that endophenotypes play a part in the relationship between genes and behavioural phenotypes.13 It is therefore important to point out that the RDoC framework emphasise the integration of knwoledge on genes, cells and neurolnal circuits with that of knowledge on cognition, emotion and behaviour.14 RDoC does not reduce psychopathology to biological causes: it is not understood that psychopathology is caused by CNS, but that it occurs in the CNS and therefore its manifestations should be detectable at this level. In this sense, the original focus is not so much biologic as biopsychosocial, although a great part of the investigation which underlies the proposal originate in the neuroscience sector.

With regard to methodology, questions have been raised about this system being based on results and that it has focused on the generation of hypothesis.34 Regarding the research strategy, we would show that the results are threatened by the proposed samples. Since the studies come from different laboratories with access to different population groups, made into samples in different ways and analysed by different researchers, RDoC should emphasis reliability. On the other hand, it should highlight its reliability but it has been suggested that the use of patients with varied symptoms and healthy subjects could pose a threat to clinical accuracy: although different disorders have similar symptoms and although aetiology underlying these is different, it may be the case that the measures are not sensitive enough to consider the disorders as separate categories. RDoC displaces its attention from disorders to mechanisms, and it therefore does not try so much to find a cut-off point for dysfunction as a dysfunctional mechanism.

Finally, one last important critical aspect with scarce mention about the RDoC framework is that, although it does not ignore the existence of environmental factors and development, the rollout of mental disease during development is not explicit in the RDoC matrix.38,39 An essential difficulty is that the presence of development processes is ubiquitous through psychopathology and that environmental factors impact every moment. For example, paediatric stress may imply progressive neurological changes which, on accumulation, may give rise to vulnerabilities for adult psychopathology. The transversal observation of clinical symptoms will not provide sufficient information on the course of the disease. The need to link the psychopathology of development as a source of information in RDoC40 has therefore been highlighted, so that physiopathogenic explanations may be generated and so that some disorders may be explained as the final result of the abnormal processes of neurodevelopment, like, for example, in the case of schizophrenia.41 Environmental influences also have a global effect, from prenatal hormonal influences42 and even social adversity factors,43,44 which are able to fit into biologic models through epigenetic factors. The link between the developmental and environmental paths would be an underlying development which is both promising and necessary,45 to explain variability in clinical manifestations between the adult and child and youth population in psychopathological areas considered equitative, such as major depressive disorder. Regarding the integration of development and environmental perspectives, the importance of the link between clinical and basic paths of the RDoC project with the methods of psychiatric and environmental epidemiology has been mentioned.46 The role of modern epidemiology as a discipline is in keeping with the RDoC Project, and would provide the capacity of this discipline to contrast and model large groups of high variability where the complete range of dimensional expression with data throughout one's whole life could be found.47

ConclusionsNeuroscience and psychiatry have developed along parallel lines. They have been artificially separated by divergence of philosophical points of focus, methods of research and treatment. However, research during recent decades has clearly proven that the separation of both disciplines is counterproductive and definitely arbitrary. Advances in the comprehension of mental illnesses require the convergence of these 2 disciplines.

Perhaps what best exemplifies this counterpositioning are the limitations of the traditional categorical systems (DSM/ICD) for guiding research into treatment.17,18 in this context, the goal of the RDoC is to improve comprehension of psychopathology through the proposal of an integrating focus which guides mental disease research. At present, the main aim is to identify the relationship between biological dysfunction and functional changes, bearing in mind neurological development and environmental factors.

Underlying RDoC is the idea that if psychopathology does not necessarily begin in what is biological it should be expressed in biological terms. After identifying the biological substrata of psychopathology, the following step is to reach a psychiatric nosology to guide treatments. However, as a research framework, it is difficult to predict the impact of their results. One key point is how RDoC findings can be transferred into a nosologic model and of specific diagnosis which could essentially guide clinical practice.

For the moment training programmes in neurosciences and translational research should be fostered so as to achieve strategic integration of basic research within clinical practice and therefore make a positive impact on mental health systems and in society.48

FundingThis study was financed with grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCII) FEDER (PI16/00165) and from the DIVE Commission for Universities and Research of the Generalitat de Catalonia (2017 SGR 452).

Conflict of interestsAll the authors declare there is no conflict of interests. The financing sources did not participate in the development of this study.

Please cite this article as: Vilar A, Pérez-Sola V, Blasco MJ, Pérez-Gallo E, Ballester Coma L, Batlle Vila S, et al. Investigación traslacional en psiquiatría: el marco Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment (Barc). 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2018.04.002