Current Topics in Breast Pathology

More infoDuring the last several years core needle biopsies, with or without vacuum assistance, have become the gold standard sampling procedure for diagnosis of palpable and non-palpable mammary lesions. The advantages of core needle biopsy over fine needle aspiration and open surgical biopsies are well-established. In the era of de-escalation of therapy and with the greater use of neoadjuvant treatment, the pathologists are ever more critical in guiding management decisions in breast pathology so there is an imperative for precision of core needle biopsy diagnosis. However, the fragmented nature or the small size of the sample, may cause diagnostic pitfalls and precise radiologic-histopathologic correlation is needed for optimal patient management. This article provides a review on several issues regarding the evaluation of core needle biopsies.

En las últimas décadas, la biopsia con aguja gruesa (BAG), asistida o no por vacío, se ha convertido en la técnica de elección para el diagnóstico de las lesiones mamarias, ya sean palpables o no palpables, mostrando claras ventajas frente a la punción aspiración con aguja fina y la cirugía diagnóstica. En la época de la desescalada de los tratamientos y del tratamiento neoadyuvante, el diagnóstico anatomopatológico de las BAGs es crítico para establecer el manejo más adecuado de cada paciente. Sin embargo, la fragmentación de la muestra o su pequeño tamaño pueden originar diversos problemas diagnósticos por lo que es preciso que haya una buena correlación radio-patológica para garantizar un buen manejo clínico de los pacientes. Este artículo revisa diferentes aspectos del manejo y diagnóstico de las biopsias con aguja gruesa.

Over the past 25 years, the diagnosis of breast pathology has suffered an evolution, facilitated by advances in imaging and in interventional procedures. After a period of extensive use of Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA), since the late 1990s, Core Needle Biopsy (CNB) has been firmly established as the gold-standard method in the initial evaluation of mammary nodules, as it provides a more definitive histological diagnosis and an adequate tissue for prognostic and predictive markers. CNB can be also used for preoperative axillary staging.1–5

CNB is a safe and cost-effective method for obtaining a non-operative diagnosis of breast lesions. Usually, it has no contraindication, but it should be performed with caution in patients who have coagulation disorders or are anticoagulated. In these situations, stronger compression after the procedure is recommended. Besides bleeding, the major complications of CNB are pneumothorax, pain, hematoma, or fainting.5,6 Since most patients get surgical excision when a malignant diagnosis is made on CNB, the seeding of malignant cells has not been of significant concern.7

The role of the pathologist in the interpretation of CNB is critical to guide risk stratification and appropriated patient management.8 In the next years digital pathology probably will suppose a revolution in diagnosis of CNB by applying artificial intelligence algorithms that would help in not just diagnosis but in prediction of patient outcome.9,10

CNB fundamentalsCNB may be used in palpable and in non-palpable masses, attached to mammographic stereotactic units, ultrasound guidance, or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). This allows imaging localization of suspicious lesions with concomitant staging of the axilla, reducing the open surgical biopsies and their morbidity.2

In CNB 14-, 12-, 11- or 8-gauge needles are used, in contrast to FNA where a 25-gauge needle is typically utilized. Two main types of CNBs are in use: the cutting type and the vacuum assisted type.

The cutting core biopsy (CCB) is a 12–14-gauge spring-loaded device that fires a cutting needle into the breast tissue. Multiple insertions are needed for sampling the target. Vacuum Assisted Biopsy (VAB) uses 8–11-gauge needles and adds a vacuum system to draw tissue into the cutting chamber to facilitate sample collection. As a result, larger specimens are obtained, with just one shot. VAB is increasingly utilized in practice, being useful in both diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.1 Nevertheless, at many institutions, VAB is mainly used for microcalcifications sampling, whereas CCB is preferred for mass forming lesions. For patients with malignant lesions, both CCB and VAB allow a complete pre-operative diagnosis, improving multidisciplinary patient decision-making.1,2,11

The pathology requisition form that accompanies a CNB specimen should ideally indicate the laterality and location of the target lesion, the radiologic imaging (i.e., mass, microcalcifications, architectural distortion, non-mass enhancement on MRI, etc.) and the level of radiologic suspicion expressed as a BIRADS category.12

Core needle biopsies managementTaking into consideration that tissue starts to deteriorate as soon as it is removed from blood supply, CNBs should be placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin immediately after procurement. Optimal fixation is required for histological detail and preservation of antigen markers, DNA and RNA. CNBs usually have a more controlled cold ischemia time than surgical specimens, being preferable for predictive and prognostic biomarker determination. In addition, to get an optimal result, recommended fixation times are no less than 6 h and no longer than 72 h. Shorter fixation times result in suboptimal antigen preservation for immunohistochemistry and longer fixation times may result in excessive protein cross-linking and diminished antigenicity.13,14

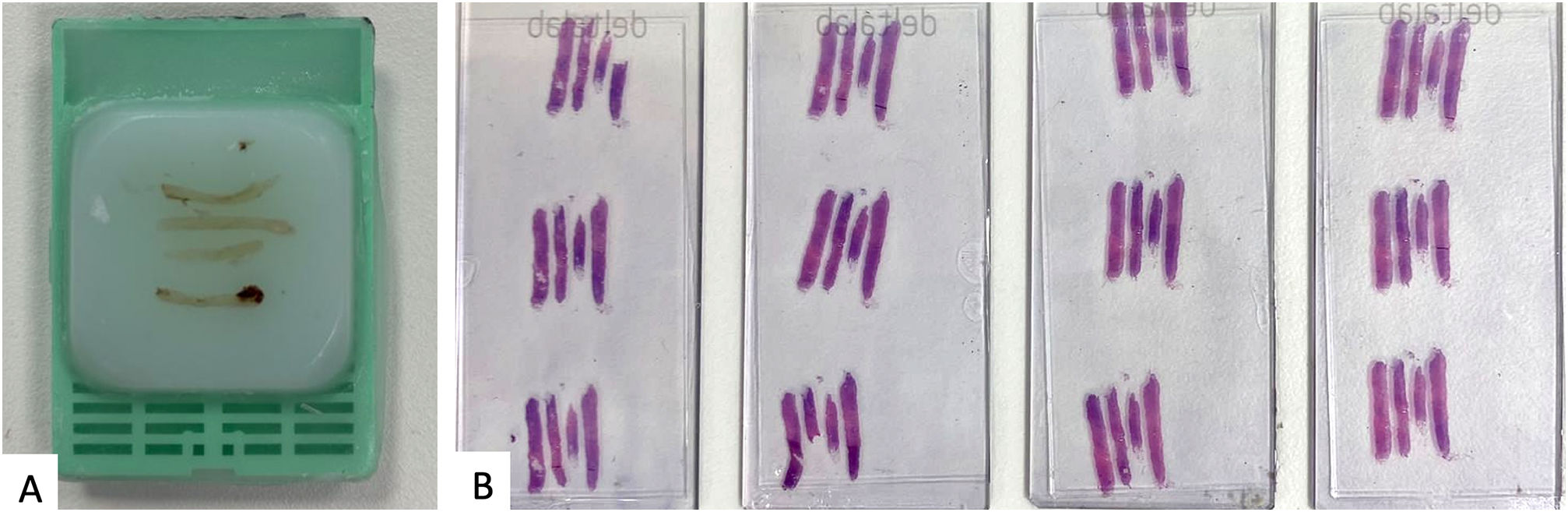

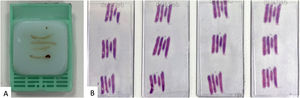

CNB specimens should be submitted entirely for microscopic evaluation including the accompanying blood clot. The diagnostic accuracy of CNB is known to increase when a higher number of cores are collected. Although, some recent studies suggest that 2 strips are the minimum number of specimens required to determine a diagnosis of malignancy, it is preferred to take at least 3–4 strips to get better concordance in prognostic and predictive biomarkers between CNBs and surgical specimens.15–17 If the obtained material is too abundant to be place in one tissue cassette, the cores must be separated into groups of approximately equal number and size, taking into account that no more than 4–5 intact cores should be placed in one cassette.18

There is no universal agreement about the number of levels that should be cut from blocks of CNB specimens to warrant a good radio-pathological correlation.2 In our institution, all the cores, up to 4, are included in the same tissue cassette. We routinely cut 4 levels from each block. In this way, all techniques are performed in the whole sample minimizing the risk of a false-negative result in the determination of biomarkers due to heterogeneity. If part of the material in needed for future clinical trials or research works, the cores will be subsequently separated into different cassettes (Fig. 1).

Immunohistochemical for prognostic and predictive biomarkers should be former performed on CNB specimens, especially in the era of neoadjuvant therapy. Their results generally correlate quite well with those on consequent surgical specimens, being lower for ki67 (about 70%) than for hormonal receptors and HER2 (about 95%).15,19–21 Despite the good agreement, some authors consider that retesting in surgical specimens may be necessary.20,22 In this way, current guidelines leave to pathologist discretion to retest in surgical specimen.13,14 It is prudent to review the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slide at the time of biomarker evaluation to ensure the histology is consistent with a breast primary tumor.3 For optimal internal quality in tests, an external control should be posed in each slide and each batch of tests to guarantee a valid result.13,14

Decalcification may be needed in CNB taken from bone metastasis. In this situation, every attempt must be made to separately process any non-calcified specimen, because immunohistochemistry performed on decalcified tissue ought to be interpreted with caution.13,14

Breast diagnostic categoriesTo make a proper interpretation of any CNB, the pathologist must have knowledge about the target radiological lesion. The BIRADS (Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System) Assessment Categories is used by radiologist to categorize radiologic findings into degree of suspicion for malignancy (Table 1). Most of CNB will be from BIRADS 4 category or higher. It is mandatory to establish a good radio-pathologic concordance and all the discordances should be review in a multidisciplinary level.3,12

American College of Radiology BIRADS assessment categories.

| Birads category | Significance | Likehood of malignancy | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birads 0 | Incomplete | Not evaluable | Need additional imaging evaluation and/or comparison with previous studies. |

| Birads 1 | Negative | 0% | Routine screening |

| Birads 2 | Benign | 0% | Routine screening |

| Birads 3 | Probably Benign | 0–2% | 6-month follow up/continue surveillance/FNA to confirm benign lesion. |

| Birads 4a | Suspicious (Low) | >2–10% | Core biopsy |

| Birads 4b | Suspicious (Medium) | >10–50% | Core biopsy |

| Birads 4c | Suspicious (High) | >50–95% | Core biopsy |

| Birads 5 | Highly suspicious | >95% | Core biopsy |

| Birads 6 | Known malignancy | 100% | Biopsy has been already done |

In this sense, the Royal College of Pathologist guidelines for non-operative diagnostic procedures and reporting in breast cancer screening, recommend categorizing the pathological findings into five diagnostic categories. They should be used in CCB and diagnostic VAB, but not in surgical specimens o VAB with excisional intend. To apply these categories, only histologic characteristics should be taken into account, nor radiological nor clinical ones.5 In our experience, the use of these diagnostic categories for CNBs, eases the communication with clinicians improving patient's management so we strongly recommend their use (Table 2).

| Category | Significance | Included lesions |

|---|---|---|

| B1 | Normal tissue | Lipomas, Hamartomas, Lactational change, Excessive crush artifacts, Bloody specimens |

| B2 | Benign Lesion | Fibroadenoma, Fibrocystic change, Sclerosing adenosis, Ductal ectasia, Breast Inflammatory Pathology, Benign Skin Lesions, Usual Hyperplasia, Columnar Changes Without Atypia, Papillomas without atypia <2 mm. |

| B3a | Uncertain malignant potential without atypia | Fibroepithelial Lesion with Cellular Stroma, Radial Scar, Papillary Lesions Without Atypia, Adenomyoepithelioma, Mucocele-like Lesions without atypia, Nipple Adenomas, Microglandular adenosis, Granular Cell Tumor, Spindle Cell Lesions. |

| B3b | Uncertain malignant potential with atypia | ADH, ALH, Classic LCIS, Papillary Lesions with Atypia, Atypical Microglandular Adenosis, Flat Epithelial Atypia, Radial Scar or Mucocele-like Lesions with Atypia. |

| B4 | Suspicious of malignancy | Cores that probably contain a carcinoma buy it is not unequivocal in the sample. |

| B5a | In situ carcinoma | DCIS, Pleomorphic or Florid CLIS |

| B5b | Invasive carcinoma | Invasive carcinoma, lymphomas, sarcomas, metastases to the breast |

| B5c | Carcinoma, not possible to differenciated invasive or in situ | Very unusual. Fragments of malignant epithelia without stroma. |

B1 category indicates a CNB with normal tissue where breast glandular structures may be present or not. Normal histology may indicate that the lesion has not been adequately sampled, but this is not mandatory. Lesions such as lipomas, hamartomas or minimal architectural distortions could lead to a normal tissue biopsy. In this way, B1 category may contain microcalcifications or lactational changes, so further multidisciplinary review is needed to dilucidated is the biopsy represents the radiologic target lesion. Excessive crush artifacts or bloody specimens are also classified as B1. To clarify interpretation, a brief description of histological finding in B1 category is recommended.5,23

B2. Benign lesionsA CNB is classified as B2 when a benign abnormality is diagnosed. This category includes a wide range of breast lesions such as fibroadenoma, fibrocystic change, sclerosing adenosis, ductal ectasia, or breast inflammatory pathology. Benign skin lesions are also categorized as B2. In some cases, it could be difficult to reach a concrete diagnosis, especially if minimal lesion is present in the biopsy which poses again to multidisciplinary approach for management. It may be prudent to classify a lesion as B1 instead of B2 if only minor changes are identified.5,23

B3. Lesion of uncertain malignant potentialB3 category refers to lesions that provide benign histology on CNB, but either are known to show histological heterogeneity or to have an increased risk of associated malignancy. It supposes around 5–9% of all diagnosis. As it includes very different levels of risk, the management of B3 lesion is still a matter of constant review.5,23–25

B3 category includes lesions such as atypical intraductal epithelial proliferation, flat epithelial atypia (FEA), in situ lobular neoplasia, fibroepithelial lesions with cellular stroma, mucocele-like lesions, radial scar, papillary lesions, and rare lesions such as adenomyoepithelioma, nipple adenomas, microglandular adenosis, granular cell tumor, spindle cell lesion such as fibromatosis or myofibroblastoma, and vascular lesions difficult to be classified.5,23

According to the Royal College of Pathologists` recommendation, the diagnosis of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH) should be reserved for surgical specimens. The definition of ADH relies in a combination of architectural, cytological, and size extend criteria, so accurate diagnosis of ADH is not possible on CNB. They suggest that the term atypical intraductal epithelial proliferation should be used instead, because the limited tissue sampled in a CNB could provide insufficient material for definitive diagnosis of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).5

Columnar changes with or without hyperplasia but without atypia should be categorized as B2, and not as B3, reserved for FEA, a columnar change that poses significant nuclear atypia.5

In situ lobular neoplasia, either atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) are classified as B3. If the distinction between ALH and LCIS cannot be reliably made on CNB, the term in situ lobular neoplasia is preferred. On the contrary, pleomorphic LCIS and florid LCIS are best classified as B5a or at least B4, as completed excision of both lesions is recommended.5,26,27

Fibroepithelial lesions with cellular stroma, stromal overgrowth, or mitotic activity suggesting the possibility of phyllodes tumor should be categorized as B3. On these scenarios, the term fibroepithelial lesion plus a description of stromal characteristics would be appropriated.5,23

Only very small papilloma <2 mm without atypia, completed biopsied by CNB, can be categorized as B2. On the contrary, when a papillary lesion is suspicious of papillary carcinoma in situ, it should be classified as B4.5,28

Atypia should also be sought in the diagnosis of radial scar and mucocele-like lesions on CNB as the chance of malignancy in subsequent surgical specimen increases significatively when atypia is present in those lesions.5,29–31

Based in a retrospective study above 1000 CNBs over a 7-year period, Rakha et al. proposed that B3 lesions were further subdivided into B3a for risk lesions without atypia and B3b for lesions that included atypia.29 This subclassification is optional in current guidelines but we consider it very useful for clinical management facilitating the interpretation of the pathology report.24

Some of the B3 lesions have been historically categorized as “high risk” because their frequent upgrade to a more significant lesion at the time of surgery. More contemporary data evaluating upgrade rates for FEA, intraductal papilloma, radial scars, benign sclerosing lesions, mucocele-like lesions and even incidental lobular neoplasia have much lower upgrade rates, about 0–4%, allowing a more conservative approach.3,24,26,32

Nevertheless, multidisciplinary discussion of each patient with a B3 diagnosis is mandatory before deciding clinical management.

B4. SuspiciousThis category is the least common (<1%) and it refers to CNBs that probably contain a carcinoma (in situ or invasive), but a definitive diagnosis cannot be provided due to technical problems or very small foci of suspicion. The management of cases classified as B4 is either a excision biopsy or a new CNB to obtain a definitive diagnosis.5,23,33 In our opinion, to clarify the best approach in each case, it could be useful to reflect on the report the suspicion we are concern about.

B5 MalignantThis category is used for cases of unequivocal malignancy on CNB. The B5 category is further subdivided in B5a, B5b, and B5c subcategories. B5a is used for in situ carcinoma, either DCIS or pleomorphic LCIS and Paget's disease. B5b is appropriated for infiltrating carcinoma and other rare malignancies that may be diagnosed in CNBs, such as malignant phyllodes tumor, sarcomas, lymphomas, or metastatic tumors on breast. B5c is reserved for situations where is not possible to say whether the carcinoma is in situ or invasive. This last subcategory is rarely applied.

If a definitive invasion less than 1 mm in size is present on a CNB that associates DCIS, categorization as B5a is recommended, reporting the small infiltrating area. A definitive diagnosis of microinvasive carcinoma cannot be made on a CNB.5,23

All invasive carcinomas should be graded according to Bloom and Richardson, Ellis modified criteria and typed on CNB unless there is a very small amount of infiltrating component. The concordance between grade on CNBs and surgical specimens can reach almost 70%. The discordance in grade is usually by one level and due to mitotic count that can be lower in CNB than in excision specimen due to limited samples.5,19,21,34,35

Looking for microcalcificationsIf microcalcifications are the indication for the CNB, a specimen radiograph should be obtained by radiologist to ensure the representativeness of the sample and the cores with microcalcifications will be ideally submitted separately. However, sometimes, microcalcifications are not to be found in pathologic examination. In most cases, additional deeper levels could solve the problem. If there are several blocks, it is useful to make a radiography to select which is the one with the microcalcifications.2,3,5,36

If the problem persists, several explanations can be given for the missing crystals. Calcified material could be ejected when it is hitten by the microtome blade. This occurs more often with larger deposits of calcification. Another explanation is the presence of calcium oxalate crystals because they don't stain with H&E but could be noticed with polarized light as they are birrefrigent. Additionally, it is important to keep in mind that several non-calcium elements in breast tissue can radiologically simulate microcalcifications, for example, suture material, tattoo pigment, hemosiderin, etc. Ocasionally, the missing calcifications are found in the stroma or within the arterial vessels. It should be included in the pathology report that the microcalcifications have been found in the CNB to facilitate the radio-pathologic correlation.5,36,37

Problematic issues in CNBThere are recognized problematic areas and potential pitfalls in CNB diagnosis. The limited sampling, tissue fragmentation or distortion make the diagnosis more difficult than in surgical specimens.

To reach a proper diagnosis, it is important to follow three general principles. First, the pathologist should be aware of clinical and radiological information. If the information is not provided, it should be sought in the medical records. Second, additional levels should be obtained if the pathological findings on the initial sections do not correlate with radiological image. Third, immunostains should be used judiciously, when necessary, to solve diagnostic dilemmas. If it is not possible to render an unequivocal diagnosis, do not over diagnose. It is adequate to give a suspicious diagnosis to get the patient to the next step for evaluation or management.2,3

In the next paragraphs, some advice and tips will be presented to solve the most problematic diagnostic dilemmas in breast core biopsies. Papillary, fibroepithelial, and other high-risk lesions will be discussed in next articles by Dr. Córdoba, Dr. Tresserra and Dr. Soler.

Usual ductal hyperplasia versus atypical ductal hyperplasia/low-grade DCISThe impact of misclassifying UDH as ADH/low grade DCIS or vice versa has significant management consequences. In the former, the patient will be sent back to the screening program, and the latter requires surgical excision with or without adjuvant hormonal or radiation therapies.

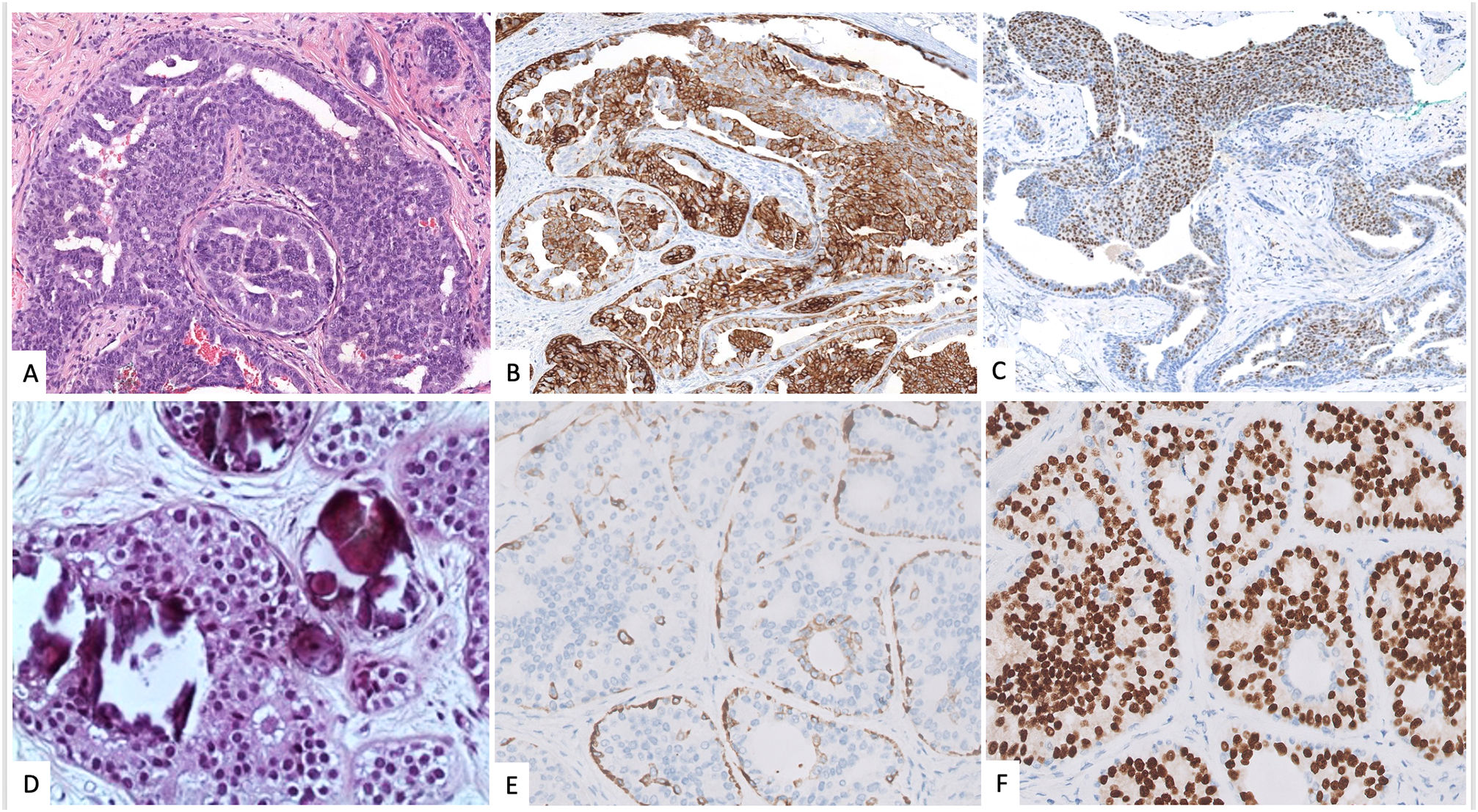

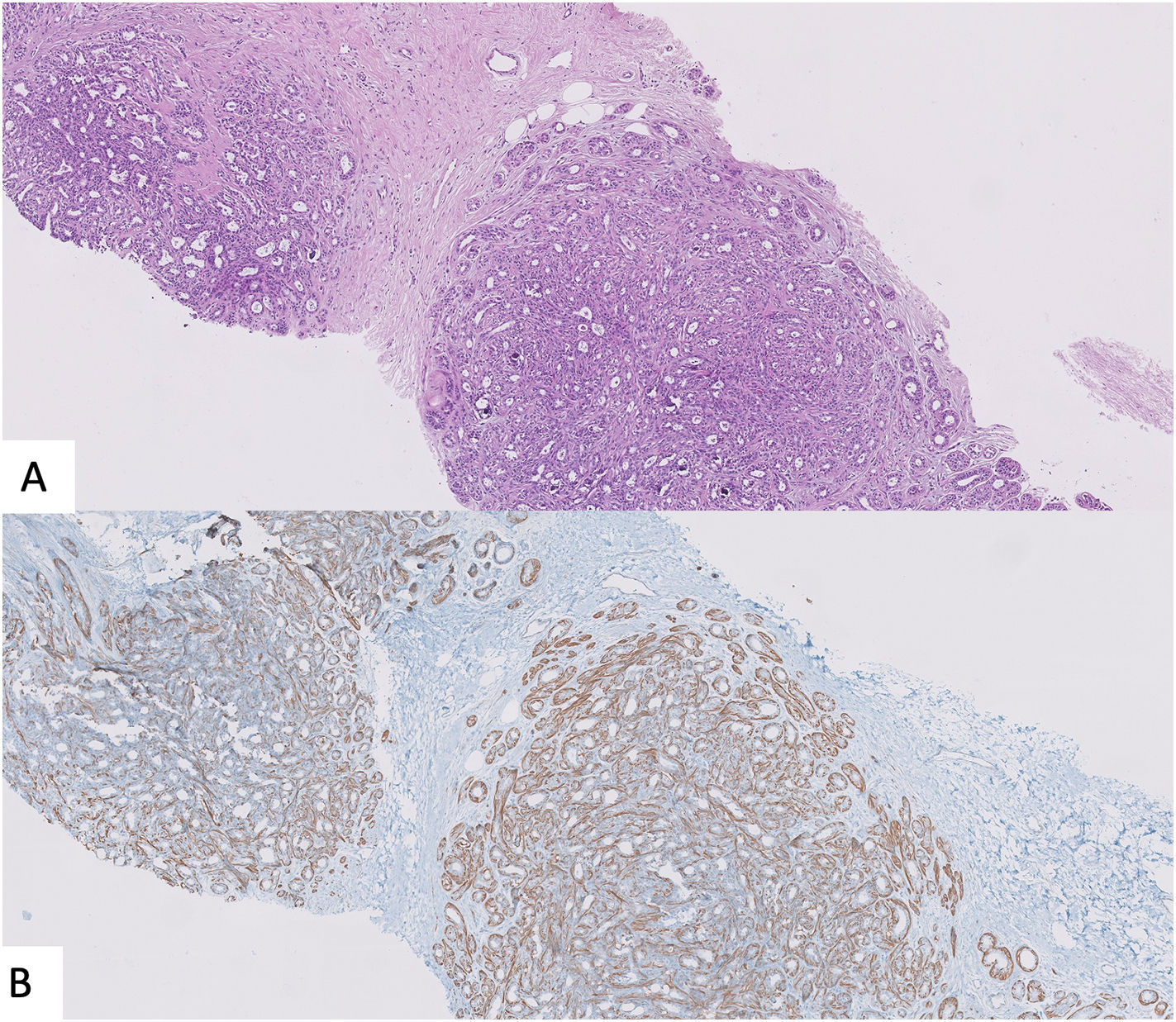

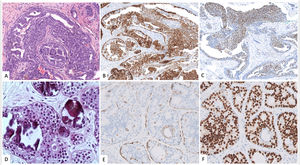

Features that facilitate distinction of UDH versus ADH/low-grade DCIS include a greater degree of cytological heterogeneity in the former plus the presence of irregular slit spaces instead of regular polarized cellular organization found in ADH/low-grade DCIS. The combination of CK5/6 and Estrogen Receptor (ER) could be also useful. UDH is composed of a mixed population of epithelial cells and thus demonstrates a heterogeneous pattern of expression with both CK5/6 and ER. On the contrary, ADH/low-grade DCIS is a monoclonal proliferation negative for CK5/6 and intensively and homogenous stained with ER3,26 (Fig. 2).

A,B,C Usual ductal hyperplasia. Messy proliferation of cells with heterogeneous expression of CK5/6 (B) and ER (C). D,E y F Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia. Homogeneous proliferation of luminal epithelial cells which lack expression of CK5/6 and intense and homogeneous expression of ER (E).

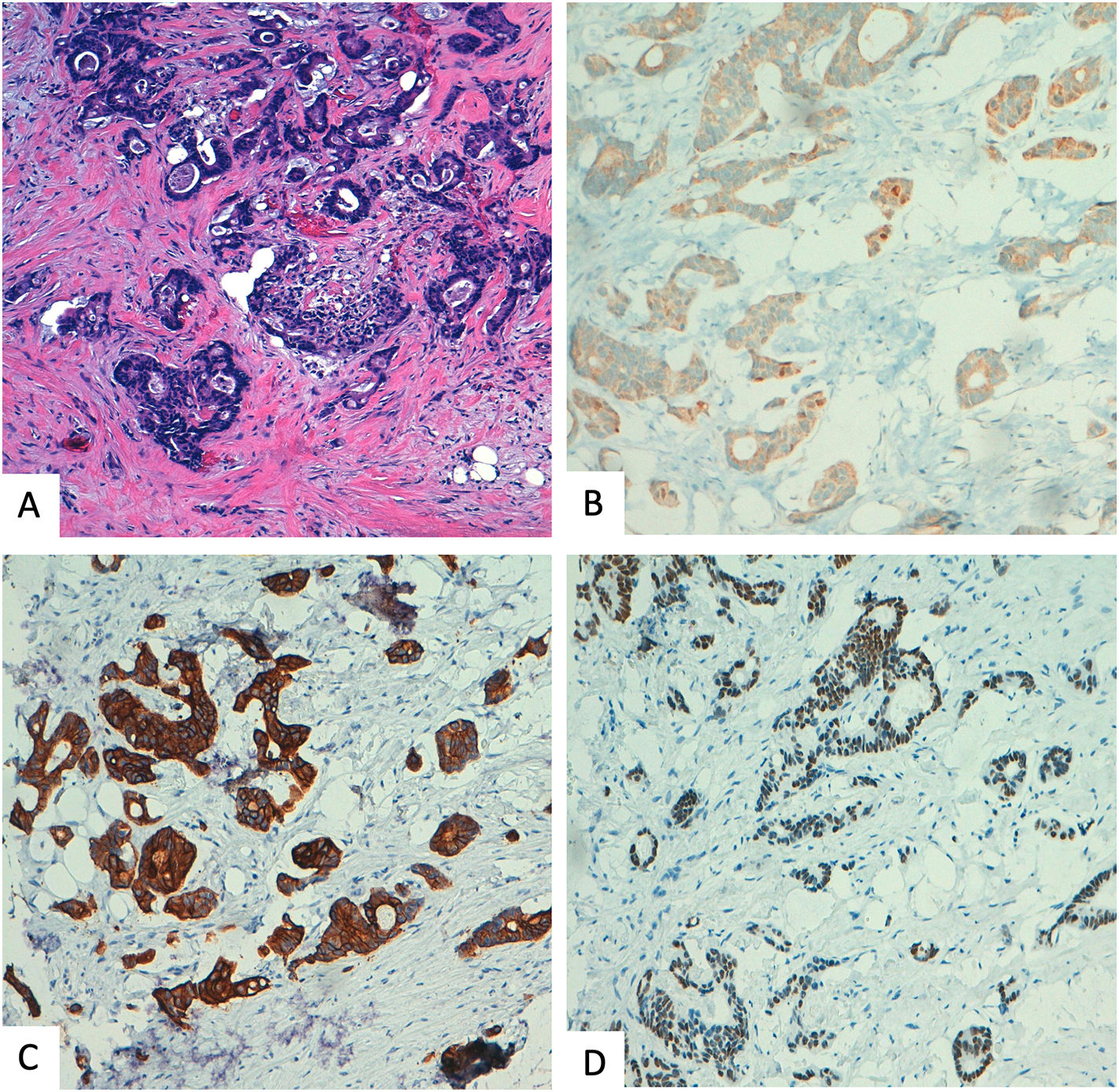

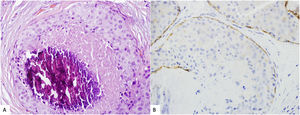

Usually, the diagnosis of LAH o classic LCIS is made straight forward. However, given the overlapping features between pleomorphic/florid LCIS and DCIS, immunostains for E-cadherin and other components of the cadherin–catenin complex, such as β-Catenin or p120, can be useful in this differential diagnosis (Fig. 3). However the distinction between LCIS and DCIS cannot rely solely on immunohistochemical markers, which must be interpreted in the context of the histological features.26,38

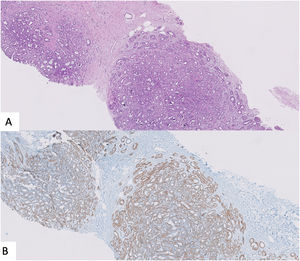

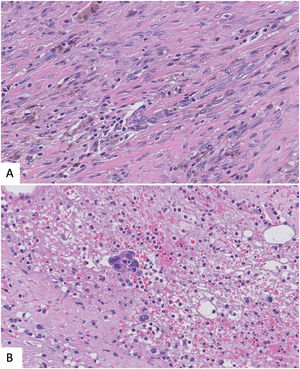

Benign sclerosing lesions versus low-grade invasive carcinomaSpecimens with a small gland proliferation should be examined on low power field to look for lobulocentricity which means that the proliferation manteins the architecture of a terminal duct lobular unit. Benign sclerosing lesions tend to preserve a lobulated contour better appreciated on low power field. In contrast, invasive low grade carcinomas have a more infiltrating border.3,26 In this sense, to rule out invasion, it is essential to look for the myoepithelial cell layer, using high power field or immunohistochemical myoepithelial markers. It is important to remmenber that some benign sclerosing lesion could have a reduction or complete loss of one or more myoepithelial markers. Thus, a panel of al least two markers, one with nuclear stain (i.e., p63, p40) and the other with membranous stain (i.e., calponin), should be used and results must be interpreted according with morphology39,40 (Fig. 4).

Another clue to make the differential diagnosis is ER expression, that it would be intense in low-grade carcinoma and heterogeneous in sclerosing lesion, unless affected by LCIS o DCIS.3,39

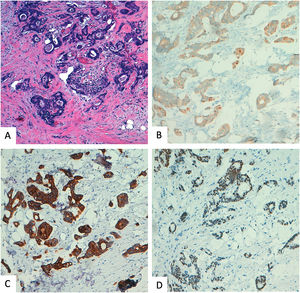

Metastasis in breast from other malignaciesAccurate distinction of metastases from primary mammary carcinoma is clinically very relevant. A wide range of tumors can metastasise to the breast, but the more frequently seen, are lymphomas, carcinomas of lung, ovary, Kidney, prostata, neuroendocrine tumors, and malignant melanoma. A full clinical history is essential to avoid missdiagnosis but some times, breast metastasis will be the first clinical sign. A metastatic carcinoma should be considered if the features of a malignancy are not typical of mammary origin. Additional clue is an extensive lymphovascular space invasion in the presence of a relatively small amount of invasive carcinoma.26,41 Clasically, it has been suggested that the absence of DCIS could raise the suspicious of metatases, but in our experience, this feature is only useful if there is a clinical orientation for metastases, as many carcinomas, specilly triple negative lack an in situ component.

Immunohistochemistry is often helpful, but no marker is completely sensitive or specific, so a panel of markers is recommended, guided by clinical records. A combination of SOX10, GATA 3, and androgen receptor has been proposed to confirm mammary origin in triple negative carcinomas. Other useful antibodies are TTF1 for pulmonary or tyroid carcinomas, CK20, and CDX2 for gastrointestinal carcinomas (Fig. 5), PAX8 and WT1 for serous ovary carcinoma, S100 and Melan A for malignant melanoma, etc39,42

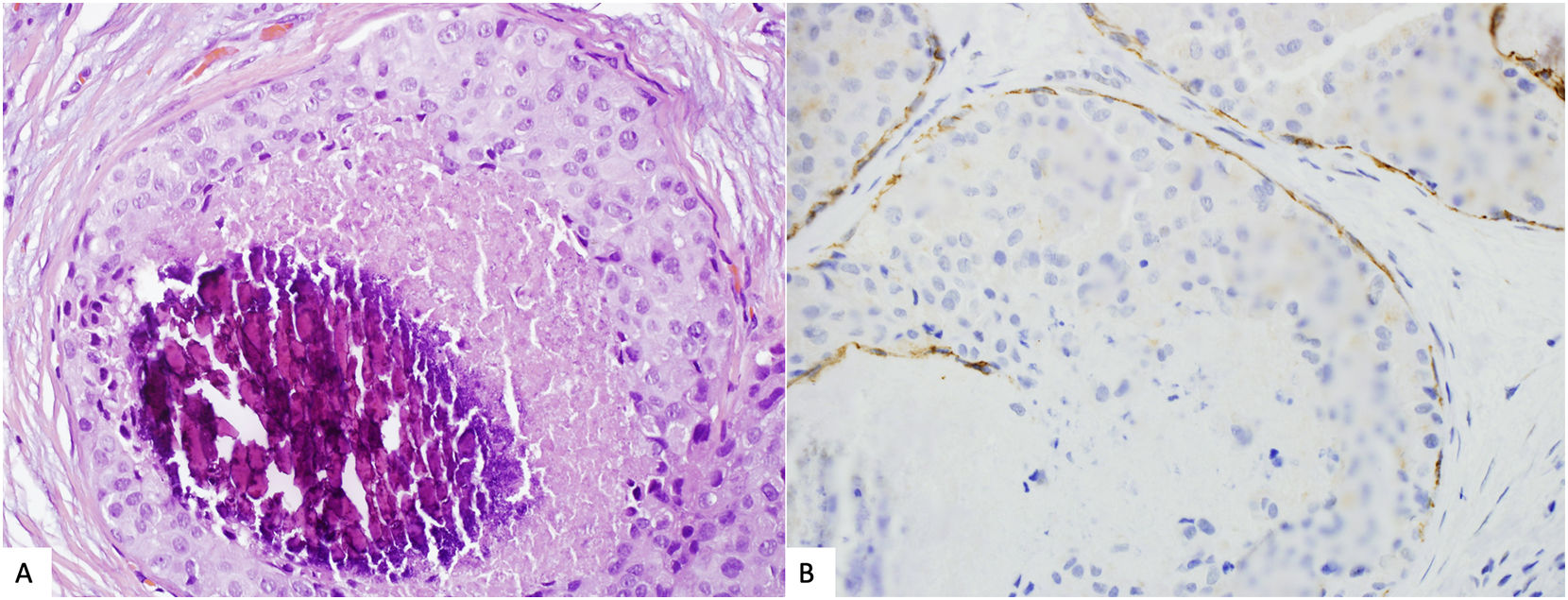

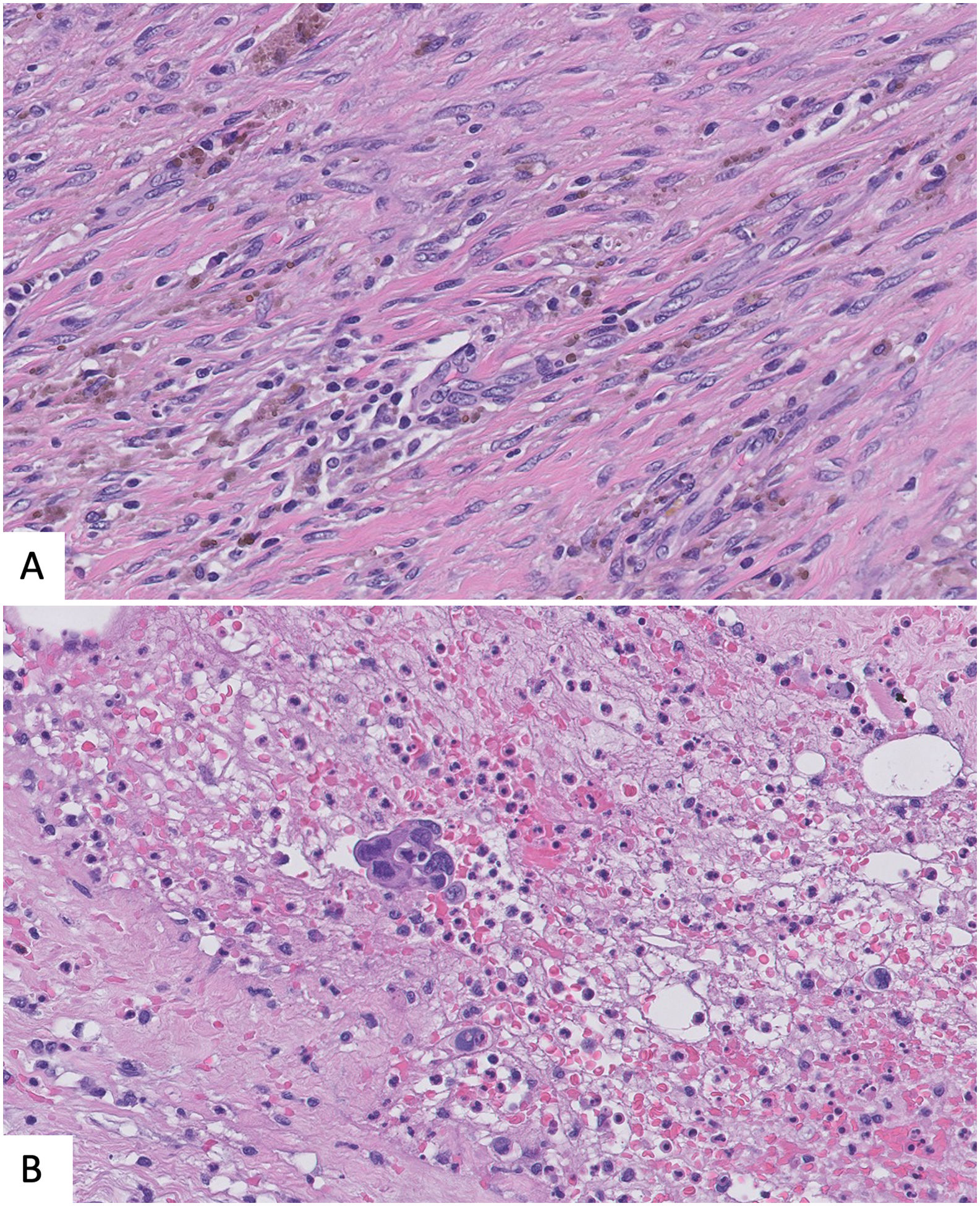

Epithelial displacement after CNBProcedural trauma-induced changes in around the CNB site can affect histopathologic evaluation of surgical specimens. Evidence of CNB track are fibrosis, hemorrage, hemosiderin deposits, and granulation tissue formation. Even more, both benign and malignant epithelial cells can be displaced into the biopsy site, needle tract, lymphovascular channels, and axillary lymph nodes. It is important to recognize this iatrogenic artifact, so that these findings are not misinterpretated as probe of invasiveness, specially in cases of benign breast lesion or in situ carcinomas.43,44

Again, immunostains for myoepithelial markers could be helpful but sometimes, the myoepithelial layer has not been displaced with the epithelium, so the lack of myoepithelial cells is not synonimus of infiltration. Looking for changes associated to previous biopsy such as hemorrage or inflamation together with the lack of desmoplastic reaction could help in the differential43,44 (Fig. 6).

Standarized reporting templatesUsing a standardized form that list most of the features needed for optimal clinical management is the best way to report a malignant result in CNB. The standardized report will give equal weightage to all components and present the histological findings in a sequence. Such checklist is an efficient way to record the diagnosis in a comprehensive manner. It eases the development of databases and homogenizes the reports between different pathologists which is needed for accreditation purposes.

Royal College of Pathologist, American college of Pathologist, and Spanish Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (SEGO), propose the use of checklists to report both invasive and in situ carcinomas diagnosed in CNB.5,45,46 The main items to be reported on CNB diagnosis of invasive carcinoma are summarized in Table 3.

Checklist for invasive carcinoma biopsy reporting.

| Invasive carcinoma CNB report | |

|---|---|

| Procedure | CCB, VAB |

| Laterality |

|

| Tumor site | Localization in breast anatomy |

| Histologic Type (WHO 2019) | |

Histologic grade (Nottingham overall score)

| Glandular/Acinar differentiationNuclear pleomorphismMitotic rate |

| Largest tumor size of invasive carcinoma/number of affected cores | |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ | Not identifiedPresent-Architectural pattern-Nuclear grade (GNI, GN II, GN III)-Necrosis |

| Lymphovascular invasion | Not identified/present |

| Microcalcifications | Not identified/present |

| TILs (Salgado et al 2015) | Percentage of stromal lymphocytes. |

Breast biomarker studies specifying:

|

|

- •

Core Needle biopsies (CNBs) are recognized as the gold-standard procedure for diagnostic breast pathology.

- •

It is recommended to use breast diagnostic categories to classify breast lesion found in CNBs.

- •

The fragmented nature or the small size of the samples, may cause diagnostic pitfalls and precise radiologic–histopathologic correlation is needed for optimal patient management.

- •

In era of neoadjuvant treatment, CNBs are the preferred sample for biomarker testing. Controlled cold ischemia and adequate fixation time are necessary to guarantee proper results.

- •

Both benign and malignant epithelial cells can be displaced into the biopsy site, needle tract, lymphovacular channels, and axillary lymph nodes causing diagnostic problems.

- •

Using a standardized form that list most of the features needed for optimal clinical management is the best way to report a malignant diagnosis in CNB.

The characteristics of the review exempt it from ethics committee approval.

FundingNo funding has been used for this review.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.