A 56-year-old man who collapsed in the street was found at autopsy to have died from mixed drug toxicity. Also present was a cholecystoduodenal fistula with an inflamed gallbladder adherent to an area of duodenal ulceration. The fistula was longstanding with significant fibrous scarring and predominantly chronic inflammation, but also with bacterial colonies, ulcer slough, and a polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration. It is uncertain whether the fistula originated from acute inflammation of the gallbladder with adherence to the duodenum (the most common aetiology) or from a penetrating duodenal ulcer, or from a combination of dual pathologies. Non-specific clinical features and illicit drug usage may have contributed to failure of diagnosis during life This case demonstrates significant rare pathology that may be more completely demonstrated with an internal autopsy examination.

En la autopsia se descubrió que un hombre de 56 años que se desplomó en la calle había muerto por toxicidad de una combinación de drogas. También se presentó una fístula colecistoduodenal con vesícula biliar inflamada adherida a un área de ulceración duodenal. La fístula era de larga data con importantes cicatrices fibrosas e inflamación predominantemente crónica, pero también con colonias bacterianas, esfacelos ulcerosos e infiltración de leucocitos polimorfonucleares. No se sabe si la fístula se originó por una inflamación aguda de la vesícula biliar con adherencia al duodeno (la etiología más común), o por una úlcera duodenal penetrante, o por una combinación de patologías duales. Las características clínicas no específicas y el uso de drogas ilícitas pueden haber contribuido al fracaso del diagnóstico durante la vida. Este caso demuestra una patología rara e importante que puede demostrarse más completamente con un examen de autopsia interna.

The presentation of cholecystoduodenal fistulas is relatively non-specific often resulting in delays in clinical identification. For example, patients have sometimes complained of abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhoea for up to 10 years prior to diagnosis.1 A case of cholecystoduodenal fistula, first discovered at autopsy, is reported in an individual who collapsed from mixed drug toxicity to demonstrate the characteristic features. Such cases are able to be more fully evaluated with internal post-mortem examinations rather than external examinations with post-mortem CT scanning.

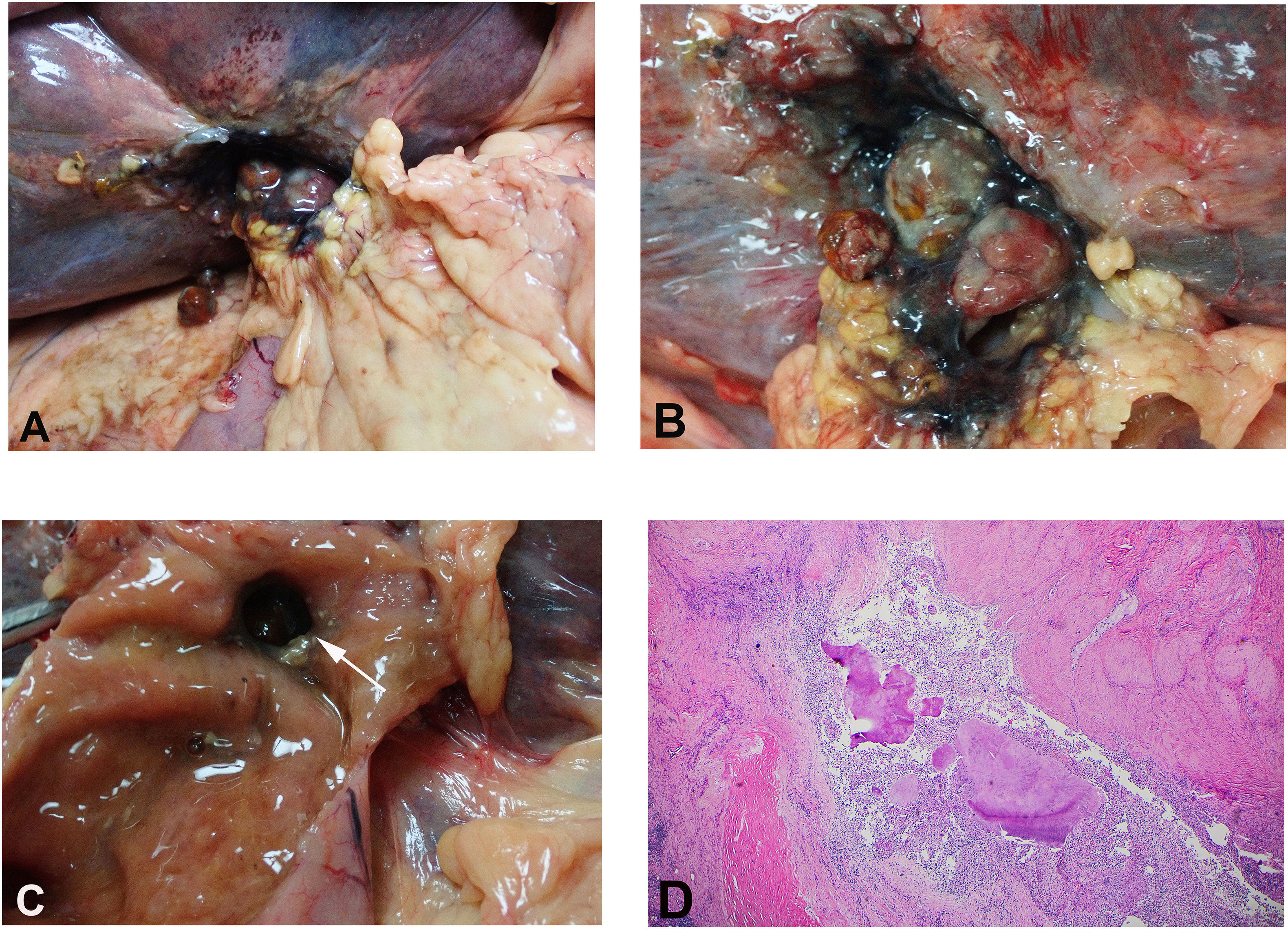

Case reportA 56-year-old man was observed on CCTV footage to leave his home address and then to sit on a footpath. He was agitated and naked and then collapsed with a possible fit. He had a past history of heavy drug use. Prolonged resuscitation occurred but to no avail. At autopsy, the body was that of an adult white male looking older than the stated age of 56 years. The length was approximately 159 cm, and the weight was 62 kg (body mass index; BMI – 24.5). The major findings were limited to the abdominal cavity where the intestines were bound down by fibrous adhesions in the right upper quadrant (Fig. 1A). CT imaging had demonstrated evidence of decomposition with possible erosion of a duodenal ulcer into the gallbladder. Subsequent dissection revealed adhesion of an inflamed gallbladder to the duodenum with a 10 mm perforating duodenal ulcer leading into a fistula to the gallbladder (Fig. 1B, C). The gallbladder was full of multiple small stones, some of which had passed into the duodenum. Histological examination of the fistula wall revealed fibrous scarring with a predominantly chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate extending through the duodenal wall into serosal tissue. Bacterial colonies were present. Focally, ulcer slough with an acute inflammatory infiltrate was also identified (Fig. 1D). Other findings included scattered emphysematous bullae with interstitial scarring of the lungs, parenchymal scarring of the liver with moderate macro-microvesicular steatosis and moderate periportal chronic inflammatory infiltrates, and focal scarring with foreign body giant cell reaction around polarisable foreign body material in the skin of the cubital fossa, in keeping with a previous injection site(s). Toxicological evaluation of blood revealed evidence of mixed drug toxicity with elevated, potentially lethal, levels of methadone (2.7 mg/L) and paroxetine (1.8 mg/L). In addition, there were elevated levels of olanzapine with tetrahydrocannabinol and therapeutic levels of paracetamol.

Small intestine that had adhered to an inflamed gallbladder has been pulled away causing tear of the gallbladder wall with exposure of several gallstones (2 of which have fallen into the peritoneal cavity.) (A). A close-up view of the inflamed gallbladder with gallstones covered by inflammatory slough (B). The gallbladder communicated by a fistula to a 10 mm ulcerated defect in the duodenum (arrow) (C). Histological examination of the fistula wall showed surrounding fibrous scarring with a predominantly chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate extending through the duodenal wall into serosal tissue. Bacterial colonies in the centre were surrounded by ulcer slough with an acute inflammatory infiltrate (Haematoxylin & Eosin, H&E x 100) (D).

Microbiological culture of the gallbladder bed revealed polymorphs with significant numbers of Gram-negative bacilli and a mixed microbiological background. Blood cultures also demonstrated a mixed growth possibly indicative of post-mortem contamination. This was most likely due to the prolonged post-mortem interval of over a week. Death was, therefore, due to mixed drug toxicity with an autopsy finding of occult cholecystoduodenal fistula formation. This was characterised by adhesion of an inflamed gallbladder to an area of duodenal ulceration. The fistula was reasonably longstanding with significant fibrous scarring and predominantly chronic inflammation. There were, however, aggregates of bacterial colonies with ulcer slough and a polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration. It is unclear from the pathology whether the fistula originated from acute inflammation of the gallbladder with adherence to the duodenum duodenum (the most common aetiology) or from a penetrating duodenal ulcer, although the latter was suggested by PMCT. Significant underlying disease included emphysema of the lungs. The only evidence of trauma was that of recent attempts at resuscitation.

DiscussionFirst described by Colombo in 1559, fistulas between the gallbladder and the gastrointestinal tract are an uncommon finding at autopsy.1 Such abnormal communications are caused by biliary or gastrointestinal disease with the majority of cases (∼90%) resulting from inflammation of the gallbladder due to cholelithiasis leading to adhesion between the gallbladder and intestinal walls with eventual necrotic breakdown and fistula formation. Other rare causes of these fistulas include peptic ulcers.2

The incidence of cases due to penetrating ulcers has declined over the years to 3%, more recently.1 Infiltrating tumours of the biliary or gastrointestinal tracts such as mucinous carcinoma of the gallbladder3 may also cause fistulas, as may certain surgical procedures such as endoscòpic sphincterotomy or choledochoduodenostomy.4 Rarely other inflammatory processes of the gallbladder such as xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis may cause fistulas.5 Other complications of these fistulas include bleeding which may be chronic manifesting as anaemia, or more acute with shock.1,6 Peritonitis is rarely a complication, occurring in only 1% of cases.1 Gallstone ileus is one of the most potentially serious complications of cholecystoentric fistulas that was first described by Bartolin in 1654.7 The initiating event is acute cholecystitis followed by adherence of the gallbladder and intestinal walls together with a possible contribution to fístula formation being pressure necrosis from a large gallstone. The majority of fistulas are cholecystoduodenal in 68% or cases, with cholecystocolic in 17%, and rarely cholecystogastric.8 Obstruction by the impacting stone most often occurs at the distal ileum in 50%–75% of cases and the proximal ileum and jejunum in 20%–40%.9 Bouveret syndrome refers to the less common occurrence of obstruction to the gastric outlet which occurs in only 3% of cases.10

Although gallstone ileus accounts for only 1%–4% of cases of mechanical intestinal obstruction there is a mortality rate of 50%, possibly influenced by the older age of patients with this complication (65–88 years)9. In the majority of cases (85%), however, gallstones in the gastrointestinal tract are eliminated by emesis or defecation.8

The reported case, therefore, demonstrates a very rare finding with a communication between an inflamed gallbladder and the duodenum. Although death was attributed to mixed drug toxicity, the possibility of the contribution of sepsis from the fistula cannot be excluded. The non-specificity of clinical features and the use of illicit drugs most likely contributed to failure of diagnosis during life. The high levels of methadone may have been associated with a need for analgesia to counter pain from the fistula.