Health institutions provide general recommendations to cope with global crises such as pandemics or geopolitical tensions. However, these recommendations are mainly based on cross-sectional evidence. The preregistered Repeated Assessment of Behaviors and Symptoms in the Population (RABSYPO) study sought to establish prospective longitudinal evidence from a cohort with a demographic distribution similar to that of the Spanish population to provide evidence for developing solid universal recommendations to reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms during times of uncertainty.

Material and methodsWe first recruited via social networks a pool of Spanish individuals willing to participate and then randomly selected some within each stratum of age×gender×region×urbanicity to conduct a one-year-long bi-weekly online follow-up about the frequency of ten simple potential coping behaviors as well as anxiety (GAD-7) and depressive symptoms (PHQ-9). Mixed-effects autoregressive moving average models were used to analyze the relationship between past behaviors’ frequency and subsequent symptom changes across the twenty-seven time points.

ResultsAmong the 1049 who started the follow-up, 942 completed it and were included in the analyses. Avoiding excessive exposure to distressing news and maintaining a healthy/balanced diet, followed by spending time outdoors and physical exercise, were the coping behaviors most strongly associated with short and long-term reductions of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Engaging in relaxing activities and drinking water to hydrate were only associated with short-term symptom reductions. Socializing was associated with symptom reductions in the long term.

ConclusionsThis study provides compelling prospective evidence that adopting a set of simple coping behaviors is associated with small but significant reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms during times of uncertainty. It also includes a layman's summary of this evidence to help develop general recommendations that serve as universal tools for enhancing mental health and well-being.

The present era is characterized by an overwhelming excess of information from multiple media sources, covering distressing and unexpected events, such as pandemics, geopolitical conflicts, and extreme weather events resulting from climate change. This surge in uncertainty about the future may have a profound mental health impact. For instance, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic led to increased anxiety and depressive symptoms in the general population 1, simultaneously triggering a profound economic crisis that further impacted mental health 2. Concurrently, ongoing wars and conflicts contribute to increased psychological distress, which, coupled with inadequate coping strategies, yields a higher prevalence of mental health illness, particularly among women and young adults 3. Similarly, there is robust evidence of the adverse effects of climate change, notably rising temperatures, on mental health and increased suicidal behavior 4.

Health authorities usually recommend coping behaviors to reduce the psychological toll of these challenging times, such as eating healthy, exercising regularly, or connecting with others 5. However, the recommendations are primarily based on studies with cross-sectional/retrospective designs 6,7, convenience samples 8, or both 9–13. These studies thus provided valuable hints but might be potentially affected by biases that preclude deriving solid recommendations. For example, in one such previous study, we found that excessive exposure to news about the COVID-19 pandemic correlated with increased anxiety 10,11. Still, it was unclear whether frequent distressing news readers become anxious due to the excess of negative information or if anxious individuals read the news frequently to alleviate their anxiety. Retrospective longitudinal evidence might partially overcome this reverse causality but might, in turn, suffer from recall bias. Finally, convenience samples with distributions different from those of the population hamper the direct extrapolation of the results to the population.

In the Repeated Assessment of Behaviors and Symptoms of the Population (RABSYPO) study, we investigated the prospective longitudinal association between coping behaviors frequency and subsequent anxiety and depressive symptoms’ change in a cohort of 942 adults using twenty-seven bi-weekly online assessments over one year during the COVID-19 aftermath 14. We first created a convenience sample via social networks; still, this sample only served as a pool of potential participants from which we randomly selected some so that the final cohort had an age, gender, regional distribution, and urbanicity similar to the Spanish population. The analysis controlled the effects of previous symptoms and measurement errors (e.g., due to individual slow mood fluctuations not fully explained by the model), and we conducted additional analyses to assess the reliability of the findings. Based on our preliminary results 10,15, we hypothesized that maintaining a healthy/balanced diet and avoiding excessive exposure to distressing news would be associated with subsequent reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms. We also expected that following a routine, pursuing hobbies, and staying outdoors would be associated with subsequent decreases in depressive symptoms.

Finally, we summarize the evidence provided by the study in a layman's text box to help develop simple recommendations for the general population to cope with these times of uncertainty.

Material and methodsWe preregistered the protocol and sample size calculations for this study 14 and followed those procedures, apart from minor modifications detailed in the Supplementary Methods. The Hospital Clínic de Barcelona research ethics committee approved the study (HCB/2020/0890), and participants provided their electronic informed consent before participating.

ParticipantsRecruitment followed a two-step strategy 14. First, we spread a short online questionnaire through social networks informing about the study and asking individuals aiming to participate to enter their age group (18–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, ≥65-year-old), the gender they identified with, the Spanish region they lived (Autonomous Communities of Spain), and the urbanicity of their municipality (<10,000 residents vs. higher). This questionnaire served us in creating a large convenience pool of potential participants of various ages, genders, regions, and urbanicity. Second, we randomly selected individuals from each age×gender×region×urbanicity stratum so that the cohort had a demographic distribution like the Spanish population.

The inclusion criteria were (a) age≥18 years; (b) living in Spain; and (c) having a mobile phone number or email address to receive our notifications. We informed participants that they could be excluded if they did not complete the first questionnaire or less than nine questionnaires with <10% missing responses. Participants who completed the minimum required questionnaires were awarded €140.

Longitudinal evaluationParticipants began the twenty-seven bi-weekly online assessments in nine waves (from October 2020 to February 2021), ensuring that special yearly events (e.g., Christmas or summer holidays) occurred at varying times of the follow-up. Likewise, we collected data for one year to include the different times of the year (in case the associations between behaviors and symptoms may vary among them).

Bi-weekly, participants completed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) items and the frequency of ten potential coping behaviors during the last two weeks (plus two random repeated GAD-7 or PHQ-9 items to detect inconsistent responses; see Supplementary Methods). We inquired about symptoms first to avoid response order bias 16. The questionnaires also included ∼10 additional items (different in each questionnaire) to collect variables used for subgroup analyses, e.g., personality dimensions or emotional intelligence (Supplementary Methods).

Assessment of coping behaviorsBased on our previous study 10, the potential coping behaviors included following a routine, socializing (outside the household), physical exercise, maintaining a healthy/balanced diet, drinking water to hydrate, excessive exposure to distressing news (about COVID-19), pursuing hobbies (or home tasks such as arranging the wardrobe), spending time outdoors (or looking outside), engaging in relaxing activities (such as listening to music, yoga, or gardening), and interacting with household members (e.g., partner or children).

As detailed in the Supplementary Methods, the questions were simple (“Over the past two weeks”: “Have you followed a healthy, balanced diet?” “Have you engaged in relaxing activities (listening to music, yoga, gardening, etc.)?” …) and participants had to choose between “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days”, or “nearly every day”.

Primary analysisThe primary analysis estimated the (linear) relationship between the frequency of the coping behaviors and subsequent anxiety and depressive symptoms’ change using population-weighted mixed-effects autoregressive moving average (ARMA) models. We used these models because they consider that future symptoms depend on past symptoms (autoregression) and that the measurement error of future symptoms also depends on the measurement error of past symptoms (moving average, i.e., the measurement error of an individual is not independent across timepoints, e.g., due to individual slow mood fluctuations not fully explained by the model). The dependent variables were the symptoms during the last two weeks, and the independent variables were the average frequency of each behavior during the previous four weeks. We fit a single model for the twenty-seven time points, e.g., the model found one single coefficient for the relationship between socializing and subsequent anxiety symptoms, combining the data from all time points. We selected 2-order autoregression and 1-order moving average because, for anxiety, depression, and their combination, they showed lower AICC than other intercept-only ARMA models (up to 2-order) 17. We chose to use the frequency of the behaviors during the previous four weeks (rather than only the previous two weeks) to match the empirical order of the autoregression component. We used weighted models to adjust for the differences between the cohort and the population (see Table 1). We set the significance level at 0.05/10 behaviors/2 measures=0.0025 to correct for multiple comparisons. To check whether the results might depend on the analytic strategy used, we repeated the analyses using alternative strategies (Supplementary Methods). The analyses were conducted with the packages nlme and lmerTest for R.18,19 Results are expressed in increases or reductions of GAD-7 or PHQ-9 score points.

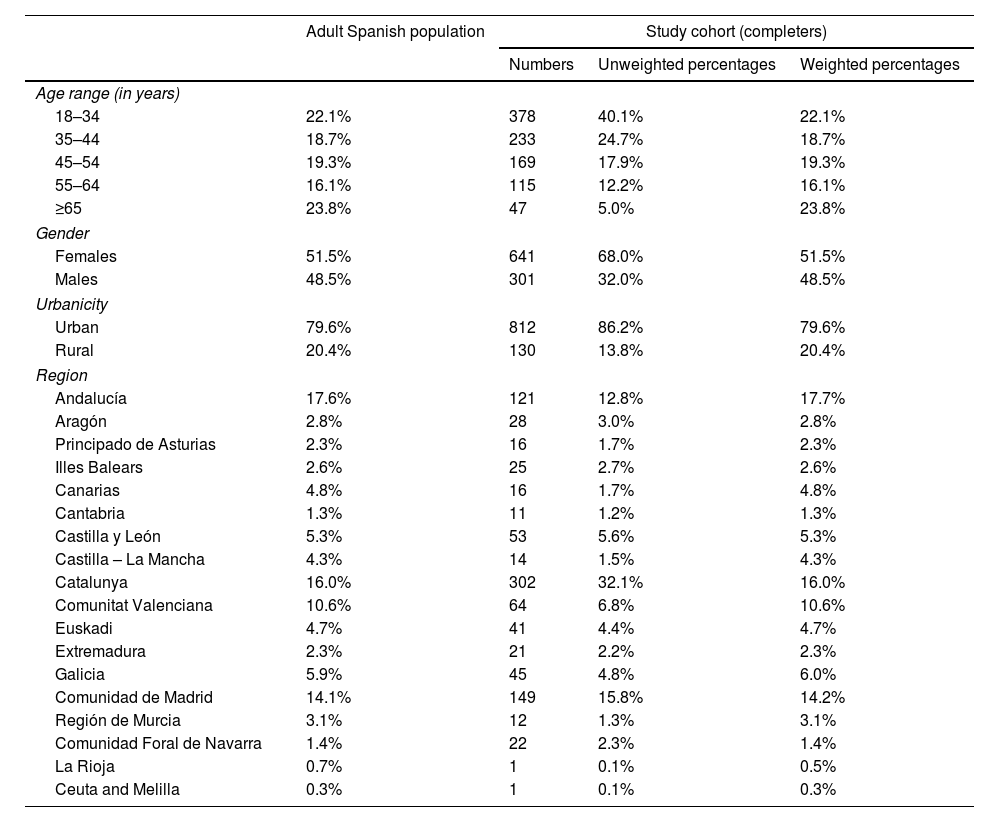

Sociodemographic characteristics of the cohort.

| Adult Spanish population | Study cohort (completers) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | Unweighted percentages | Weighted percentages | ||

| Age range (in years) | ||||

| 18–34 | 22.1% | 378 | 40.1% | 22.1% |

| 35–44 | 18.7% | 233 | 24.7% | 18.7% |

| 45–54 | 19.3% | 169 | 17.9% | 19.3% |

| 55–64 | 16.1% | 115 | 12.2% | 16.1% |

| ≥65 | 23.8% | 47 | 5.0% | 23.8% |

| Gender | ||||

| Females | 51.5% | 641 | 68.0% | 51.5% |

| Males | 48.5% | 301 | 32.0% | 48.5% |

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Urban | 79.6% | 812 | 86.2% | 79.6% |

| Rural | 20.4% | 130 | 13.8% | 20.4% |

| Region | ||||

| Andalucía | 17.6% | 121 | 12.8% | 17.7% |

| Aragón | 2.8% | 28 | 3.0% | 2.8% |

| Principado de Asturias | 2.3% | 16 | 1.7% | 2.3% |

| Illes Balears | 2.6% | 25 | 2.7% | 2.6% |

| Canarias | 4.8% | 16 | 1.7% | 4.8% |

| Cantabria | 1.3% | 11 | 1.2% | 1.3% |

| Castilla y León | 5.3% | 53 | 5.6% | 5.3% |

| Castilla – La Mancha | 4.3% | 14 | 1.5% | 4.3% |

| Catalunya | 16.0% | 302 | 32.1% | 16.0% |

| Comunitat Valenciana | 10.6% | 64 | 6.8% | 10.6% |

| Euskadi | 4.7% | 41 | 4.4% | 4.7% |

| Extremadura | 2.3% | 21 | 2.2% | 2.3% |

| Galicia | 5.9% | 45 | 4.8% | 6.0% |

| Comunidad de Madrid | 14.1% | 149 | 15.8% | 14.2% |

| Región de Murcia | 3.1% | 12 | 1.3% | 3.1% |

| Comunidad Foral de Navarra | 1.4% | 22 | 2.3% | 1.4% |

| La Rioja | 0.7% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.5% |

| Ceuta and Melilla | 0.3% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.3% |

We used non-linear ARMA analyses (comparing [not at all or nearly every day] vs [several or more than half the days] behavior frequency) to assess whether the symptom changes associated with the coping behaviors were progressively larger when the individual conducted behavior more frequently or, instead, the behavior was only associated with symptom changes when conducted (nearly) all days but not if conducted most (but not nearly all) of the days.

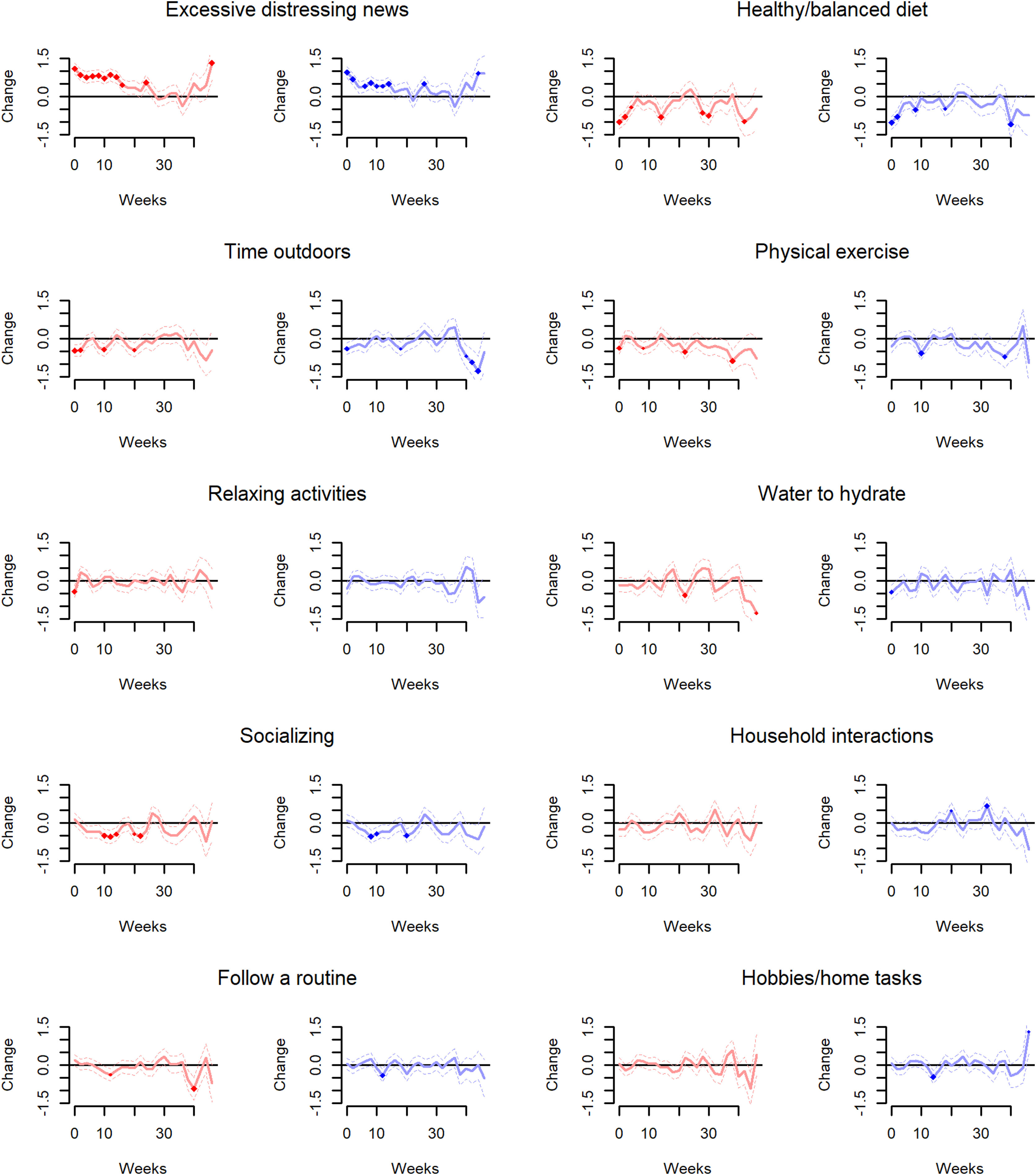

Long-term analysisTo explore the long-term associations between coping behaviors and symptoms, we repeated the primary ARMA analyses, though adding gaps (from 2 to 46 weeks) between the behaviors and the symptoms. For instance, the primary analysis investigated the association between behaviors conducted during weeks 1–4 and symptoms experienced during weeks 5–6. Here, we investigated the association between behaviors conducted during weeks 1–4 and symptoms experienced during weeks 7–8, 9–10, 11–12, etc.

Creation of a layman's summaryFinally, we selected the statistically significant results from the primary analysis to create a layman's text box to help develop simple recommendations. We also added the information from the non-linear and long-term analysis (e.g., to specify if the symptom reductions associated with a behavior are short-term, long-term, or both).

ResultsDescription of the cohortWe randomly selected and contacted 1256 potential participants, 1049 enrolled in the one-year longitudinal evaluation, and 942 successfully finished it (retention rate=90%), leading to 22,576 completed questionnaires (compliance=89%). Demographic characteristics for completers and non-completers and their comparison with the Spanish adult population are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Completers and non-completers only showed minor differences. The analyses below were conducted using data from the 942 completers.

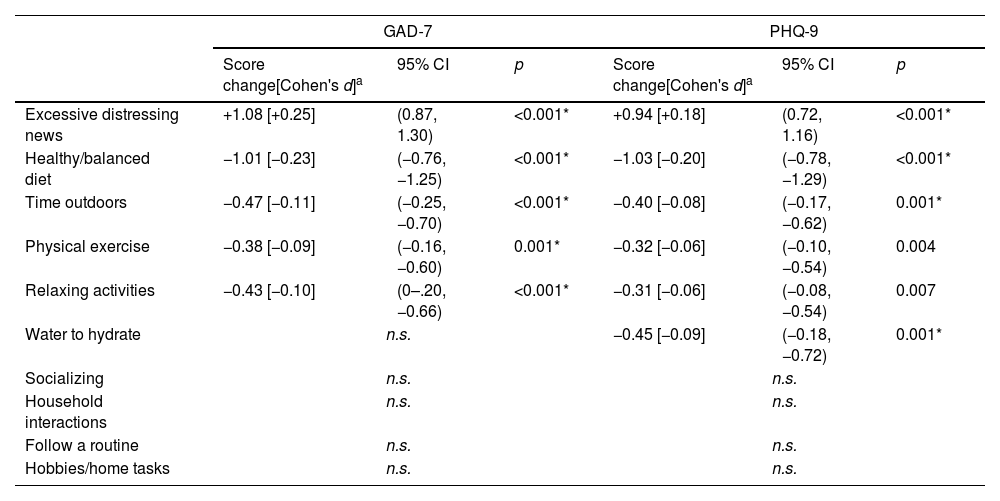

Primary analysisAs shown in Table 2, behaviors associated with subsequent reductions of anxiety and depressive symptoms were maintaining a healthy/balanced diet (one point decrease in GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores, roughly corresponding to Cohen's d=−0.22), spending time outdoors (or looking outside) (0.5 points decrease in GAD-7 score and 0.4 in PHQ-9 score, d=−0.09), and physical exercise and engaging in relaxing activities (both behaviors showed 0.4 points reduction in GAD-7 score and – at trend level – 0.3 in PHQ-9 score, d=−0.08). Additionally, drinking water to hydrate was associated with depressive symptom reductions (0.5 decrease in PHQ-9 score). Conversely, excessive exposure to distressing news (about COVID-19) was associated with subsequent increases in anxiety and depressive symptoms (1.1 increase in GAD-7 score and 0.9 in PHQ-9 score, d=+0.22). The main results were similar when using different analytic strategies (Supplementary Results and Supplementary Tables 3–8) or in subgroup analyses (Supplementary Results and Supplementary Tables 9–11).

Relationship between current behaviors’ frequency and subsequent anxiety and depressive symptoms.

| GAD-7 | PHQ-9 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score change[Cohen's d]a | 95% CI | p | Score change[Cohen's d]a | 95% CI | p | |

| Excessive distressing news | +1.08 [+0.25] | (0.87, 1.30) | <0.001* | +0.94 [+0.18] | (0.72, 1.16) | <0.001* |

| Healthy/balanced diet | −1.01 [−0.23] | (−0.76, −1.25) | <0.001* | −1.03 [−0.20] | (−0.78, −1.29) | <0.001* |

| Time outdoors | −0.47 [−0.11] | (−0.25, −0.70) | <0.001* | −0.40 [−0.08] | (−0.17, −0.62) | 0.001* |

| Physical exercise | −0.38 [−0.09] | (−0.16, −0.60) | 0.001* | −0.32 [−0.06] | (−0.10, −0.54) | 0.004 |

| Relaxing activities | −0.43 [−0.10] | (0–.20, −0.66) | <0.001* | −0.31 [−0.06] | (−0.08, −0.54) | 0.007 |

| Water to hydrate | n.s. | −0.45 [−0.09] | (−0.18, −0.72) | 0.001* | ||

| Socializing | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

| Household interactions | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

| Follow a routine | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

| Hobbies/home tasks | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

The table includes summarized descriptions of behaviors. Please see “Methods: Assessment of coping behaviors” for full descriptions. Score change: difference in subsequent symptom score between conducting the behavior nearly all days vs. never; GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

These analyses showed that engaging in relaxing activities was associated with a subsequent anxiety reduction only when conducted (nearly) all days (Supplementary Table 12). The associations involving excessive exposure to distressing news (about COVID-19) and spending time outdoors (or looking outside) also exhibited trends that deviated from linearity. However, the relationship was still ordinal (i.e., the more frequent the behavior, the stronger the symptom change).

Long-term analysisFig. 1 shows that maintaining a healthy/balanced diet, spending time outdoors (or looking outside), or engaging in physical exercise were also associated with reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms when the latter were measured after a gap of up to 44 weeks. We also observed that excessive exposure to distressing news (about COVID-19) was still associated with symptom increase when measured after a gap of up to 46 weeks. Finally, contrary to the primary (short-term) analysis, we observed that socializing (outside the household) was associated with symptom reductions when the latter were measured after 8–22 weeks.

Relationship between current behaviors’ frequency and long-term anxiety (red) and depressive (blue) symptoms. This figure shows the results of the autoregressive moving average (ARMA) analysis, adding gaps (from 2 to 46 weeks) between the ten studied behaviors and the changes in anxiety (red) and depressive (blue) symptoms. The x-axis represents the symptoms’ change, whereas the y-axis represents the weeks since the behavior. The figure includes summarized descriptions of behaviors. Please see “Methods: Assessment of coping behaviors” for full description.

We summarize the findings in Box 1.

Associations between simple behaviors and subsequent changes in anxiety and depressive symptoms – results from the RABSYPO study.

| 1. Maintaining a healthy/balanced diet and exercising regularly correlated with short-and long-term reductions of anxiety and depressive symptoms. | |

| The study found that after eating healthy or doing physical activity, individuals felt more relaxed and positive both in the short and long term. These behaviors are associated with overall benefits and have been already recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO):-https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet-https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 | |

| 2. Reading an excess of negative news correlated with short-and long-term increases in anxiety and depressive symptoms. | |

| The study, conducted during the aftermath of COVID-19, found that after excessive exposure to negative news, individuals felt more anxious and depressed both in the short and long term. The WHO also recommended minimizing exposure to COVID-19 news causing anxiety or distress:-https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf | |

| 3. Spending time outdoors correlated with short-and long-term reductions of anxiety and depressive symptoms. | |

| The study found that after staying outdoors, individuals felt more relaxed and positive both in the short and long term. Trusted publishers of expert health information, such as The Mayo Clinic Press,alsorecommend spending time outdoors:-https://mcpress.mayoclinic.org/mental-health/the-mental-health-benefits-of-nature-spending-time-outdoors-to-refresh-your-mind/ | |

| 4. Engaging in relaxing activities correlated with short-term reductions of anxiety. | |

| The study found that after doing calming activities (nearly) every day, individuals felt more relaxed in the short term. Previous meta-analyses have also found relaxation may decrease anxiety:-https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-022-00541-y | |

| 5. Drinking water to hydrate correlated with short-term reductions of depressive symptoms. | |

| The study found that after drinking water to hydrate, individuals felt more positive in the short term. According to the recommendations by the European Food Safety Authority, the adequate water intake is about 2.5l per day for males and 2 for females (more if pregnant or lactating).-https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/1459 | |

| 6. Socializing with others correlated with long-term reductions of anxiety and depressive symptoms | |

| The study found that after interacting with people, individuals felt more relaxed and positive in the long term. This finding agrees with previous meta-analyses finding health benefits of having a good social connection structure:- For instance:https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13072 | |

These images were created with the assistance of DALL·E 3.

The RABSYPO study provides compelling prospective longitudinal evidence of the relationship between conducting several simple coping strategies and small reductions of anxiety and depressive symptoms during periods of uncertainty, such as those induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. In agreement with our hypotheses, avoiding excessive exposure to distressing news (about COVID-19) and maintaining a healthy/balanced diet were associated with future reductions of anxiety and depressive symptoms across the whole population, exhibiting consistency and robustness across subgroups. Spending time outdoors (or looking outside) was also associated with symptom reduction. Contrary to our hypotheses, we also observed relevant symptom reductions after physical exercise and short-term reductions after engaging in relaxing activities and drinking water to hydrate. At the same time, following a routine or pursuing hobbies were not associated with symptom changes. Socializing (outside the household) was associated with significant symptom reductions in the long term.

Avoiding excessive exposure to distressing newsExcessive exposure to distressing news (about COVID-19) was strongly associated with mild increases in anxiety and depressive symptoms in the short and long term, aligning with our preliminary results and existing research on coping behaviors 10,12,13.

While individuals are responsible for selecting news sources, we also emphasize the need for social media producers to recognize the psychological impact of their content. Information sharing on social media can enhance awareness and compliance 7,20, but spreading misinformation during distressing events contributes to heightened fear and panic 21. This phenomenon of infodemics, characterized by the rapid proliferation of low-quality online information, warrants attention to international authorities to safeguard the mental well-being of the whole population. Similarly, while constructively framing new stories of awareness-raising actions on climate change positively affects mental health and well-being, negative news on climate change stories may lead to eco-anxiety and hopelessness 22. Contrary to the belief of more distressing events today, the concern may be the overwhelming volume of their coverage and the potential for misinformation 20,21.

Maintaining a healthy diet and engaging in physical exerciseConsistent with our preliminary investigation 10, maintaining a healthy/balanced diet was strongly associated with mild reductions of anxiety and depressive symptoms over the short and long term. This association aligns with prior studies indicating that healthy dietary patterns significantly lower the risk of depressive symptoms 23. Although the precise influence of nutrients on mental health remains unknown, potential mechanisms include improving the brain's nutritional intake and stabilizing the gut microbiome. For instance, studies suggest that diets high in glucose or saturated fats may contribute to inflammation, increasing depressive symptoms and the risk of mental illness 23,24. Further research is essential to establish a causal relationship between lifestyle, gut microbiome, and mental health.

Contrary to our pilot study 10, we observed a significant association between physical exercise and short and long-term anxiety and depressive symptom reductions. This finding aligns with previous research on using exercise to improve mental health in general 25 and during health emergencies 9,11,26. For instance, Lau and colleagues suggested that positive lifestyle changes during the SARS epidemic 2003, like exercise, protected individuals from the negative impacts of the epidemic 9. This finding also agrees with robust previous experimental evidence that physical exercise improves symptoms across mental disorders 27.

These lifestyle protective factors 23,28 may improve anxiety and depressive symptoms via specific mechanisms such as those commented on above, but they also improve physical health. And good physical health is associated with good mental health 29. Not only this, but good mental health is in turn associated with good physical health again 30, in a virtuous circle reminiscent of the Roman poet Juvenal's famous phrase “mens sana in corporesano” (a healthy mind in a healthy body). Indeed, there is evidence that mentally healthy individuals follow healthier diets and do more physical activity 31, creating a larger virtuous circle that may sustain and extend the positive effects of these simple lifestyle coping behaviors.

Spending time outdoorsIn line with our pilot study 10, spending time outdoors (or looking outside) was associated with slight reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms, both in the short and long term. Evidence suggests that exposure to green and blue spaces is associated with mental and physical health benefits, as a restorative environment and encouraging social interaction and physical activity 32. However, we must acknowledge that the Spanish population experienced a very restrictive lockdown, and the subsequent freedom to go outdoors may have slightly overestimated the association due to the joy associated with that freedom.

Engaging in relaxing activitiesEngaging in relaxing activities was associated with a slight short-term reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms, consistent with other previous research on coping strategies during health emergencies 9,10. However, this association was only significant when participants performed these activities (nearly) daily. Recent studies highlight the positive influence of relaxing activities, like yoga, on mental health, particularly anxiety and depressive symptoms, offering benefits through stress reduction, emotion regulation, and mind-body connection 33,34.

Drinking water to hydrateContrary to our previous findings 10, our study showed that drinking water to hydrate was associated with a slight short-term reduction of depressive symptoms. Numerous studies investigating hydration's impact on mood suggest mild dehydration may impair cognitive function and disrupt mood 35.

SocializingOur results indicate that engaging in social activities (outside the household) only showed a significant association with anxiety and depressive symptoms reductions in the long term. This finding aligns with broader literature suggesting that, during times of uncertainty, being able to contact relatives or friends and receiving social support can have a substantial positive impact on mental health and overall well-being 10–12. The long-term implications of socializing highlight the potential protective effect of extended social networks during challenging periods.

We must acknowledge that the RABSYPO study was conducted in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic when individuals were still afraid of COVID-19 contagions. Thus, we cannot exclude that this contagion fear may have overshadowed the short-term benefits of socializing.

LimitationsThis study has limitations. Firstly, we collected coping behaviors using simple questions (e.g., “Have you followed a healthy, balanced diet?”) rather than properly validated questionnaires, which could be problematic for some behaviors such as following a healthy/balanced diet. However, we must note that most individuals know what a healthy/balanced diet means 36. Secondly, individuals received economic compensation for completing the follow-up (i.e., 140€), which could have motivated the participation of individuals who otherwise would not have been interested. This economic compensation could have increased compliance at the potential cost of decreasing response accuracy, resulting in measurement error that would have reduced the statistical power to detect the associations between coping behaviors and symptom changes. On the positive side, though, an increase in compliance meant an increase in the representativity of the cohort. Thirdly, the study was observational, for which we cannot completely rule out that individuals who maintain a healthy diet or exercise regularly might have more positive mental health in the first term. However, we used ARMA models to control previous symptoms and measurement errors, leaving little room (if any) for that possibility. Finally, there is also the possibility that participants modified their behavior in response to the assessments (i.e., the Hawthorne effect). However, we did not focus on the behavioral changes but on the impact of these changes on anxiety and depressive symptoms.

ConclusionThe post-COVID-19 pandemic era has seen a significant increase in mental health issues 37, urging the enhancement of primary prevention, mainly through universally applicable measures that do not require professional assistance 38. The coping behaviors identified in the RABSYPO study fulfill this requirement due to their simplicity, expected acceptance (the general population likely has more reservations about psychotropic drugs or psychotherapy than about a healthy diet), and expected cost-effectiveness. While their effects are smaller than the established treatments for anxiety or depression, these simple coping behaviors may represent essential tools for promoting mental health, enhancing the overall well-being of the entire population 39, and potentially fostering primary prevention 40.

We thus strongly recommend the population avoid excessive exposure to distressing news, maintain a healthy/balanced diet, spend time outdoors, practice physical exercise, and engage in relaxing activities regularly (Box 1).

Funding sourcesThis work was supported by the AXA Research Fund via an AXA Award granted to JR from the call for projects “Mitigating risk in the wake of the Covid-19 Pandemic”. The funder did not have a role in study design, data collection and analysis, publication decision, or manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interestEV has received grants and served as a consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities (unrelated to the present work): AB-Biotics, Abbott, Abbvie, Aimentia, Angelini, Biogen, Biohaven, Boehringer Ingelheim, Casen-Recordati, Celon, Compass, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ethypharm, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo Smith-Kline, Idorsia, Janssen, Lundbeck, Novartis, Organon, Otsuka, Rovi, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda, and Viatris. AF has received speaker fees and educational support from Abbot, Vatris, Lundbeck, and Janssen, unrelated to the present work. IG has received grants and has served as a consultant, advisor, or CME speaker for the following entities (unrelated to the present work): ADAMED, Angelini, Casen Recordati, Esteve, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Lundbeck-Otsuka, Luye, SEI Healthcare, Viatris outside the submitted work. She also receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Elsevier, and Editorial Médica Panamericana. JR has received CME honoraria from Inspira Networks for a machine learning course promoted by Adamed outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

AXA Research Fund funded this project via an AXA Award granted to JR from the call for projects “Mitigating risk in the wake of the Covid-19 Pandemic”. LF thanks the support from an educational grant from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FI20/00047). CT and IG thanks the support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI20/00344, PI23/00822), integrated into the Plan Nacional de I+D+I, and co-financed by ERDF Funds from the European Commission (“A Way of Making Europe”). JR thanks the support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) (CPII19/00009) and the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement (2021 SGR 1128).